LONG-TERM SERVICES AND SUPPORTS

Context and Gaps:

Long-Term Services and Supports in the United States

Joanne Lynn

Director, Center for Elder Care and Advanced Illness

Altarum Institute

Cheryl Phillips

President and Chief Executive Officer

Special Needs Plans Alliance

Most Americans will need long-term services and supports at some point in their lives, said Joanne Lynn, the director of the Altarum Institute’s Center for Elder Care and Advanced Illness, and the current prev-

alence of Americans needing these services and supports will double within 15 years (Favreault and Dey, 2016). Cheryl Phillips, the president and chief executive officer of the Special Needs Plans Alliance, provided an introductory overview and reported that currently more than 12 million people use long-term services and supports (Anthony et al., 2017), with long-term care occurring in many settings, including at home and in skilled nursing facilities, rehabilitation facilities, long-term care hospitals, nursing homes, and assisted living facilities. How care is paid for in these settings depends on specific Medicare and Medicaid regulations as well as on an individual’s personal finances. Phillips said that long-term services and supports include custodial, residential, and community-based services, the majority of which are private pay. Some states are moving to managed Medicaid long-term services and supports.

Long-term care is expensive, Phillips said, with the average nursing home stay costing around $84,000 per year and the average assisted living facility costing approximately $44,000 per year (Genworth Financial, 2016). She said that in-home care averages $150 for 8 hours, with an average annual cost of $46,000. For the United States as a whole, long-term care costs $275 billion annually (Pennsylvania Health Care Association, n.d.). States are moving quickly to managed long-term services and supports as they face increasing budget challenges and look to cut back on Medicaid benefits. These services, Phillips said, are typically funded under waivers and are not typically considered a Medicaid essential benefit. Medicaid reform, she added, is likely to involve block grants, further limiting funds available for long-term services and supports. Contrary to what many in the public believe, she said, Medicare only pays for “skilled services” and not “daily support services” or personal care.

Lynn said that most Americans do not have plans for covering the anticipated 2-year duration of self-care disability, given that the average person entering retirement has no retirement savings beyond Social Security (Morrissey, 2016). As a result, she said, “we have enormous numbers of people coming to old age without adequate retirement security, without assets, and facing long-term disability,” and the burden of providing long-term services and supports to most Americans will fall on family and friends who are also getting older.

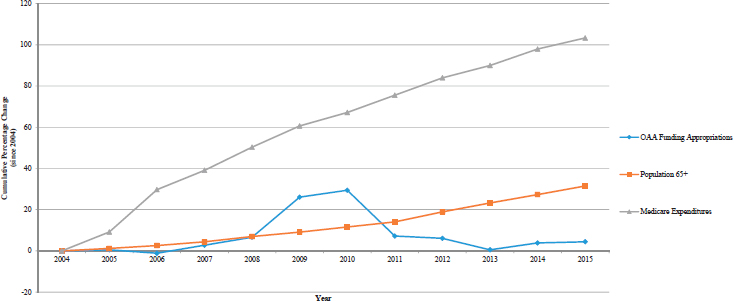

Lynn said that the nation’s support for long-term care and geriatric care is, in her opinion, woefully inadequate. Despite increases in Medicare spending and increasing numbers of older Americans, federal spending on long-term services and supports under the Older Americans Act has fallen and is now flat (see Figure 6-1), with proposals for further cuts. Lynn noted, too, that the United States spends nearly twice as much on medical care and about half as much on social supports as the average

SOURCES: Lynn presentation, February 13, 2018. Data from Parikh et al., 2015.

spending of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries (Bradley and Taylor, 2013).

Adding to the challenges of providing long-term care for those in need is the fact that the workforce is insufficient to meet demand. Phillips suggested the direct care workforce will need to increase 50 percent by 2030 to meet anticipated demand. Few clinicians are prepared to work in a palliative care setting or are trained in geriatrics. A few states have minimum staffing requirements for long-term care facilities, but most states do not set minimums. As a result, Phillips said, one direct care worker may have to deal with as many as 18 people, with perhaps one licensed practical nurse on a unit and a registered nurse available only during the weekdays. There seems to be an expectation, Phillips said, that families, who are already burdened and already provide uncompensated care valued at $450 billion annually (Family Caregiver Alliance, 2015), will fill in the gaps; however, as she noted, most families do not know how to approach providing the kind of care many individuals will require. In addition, forcing families to provide long-term care will translate into additional losses of income, retirement benefits, and opportunities for promotion that the caregiver could have had at work, which in turn will often compound the financial stress many families experience both before and after their family member is gone.

Physician-Assisted Death and Long-Term Services and Supports

Cheryl Phillips

President and Chief Executive Officer

Special Needs Plans Alliance

Joanne Lynn

Director, Center for Elder Care and Advanced Illness

Altarum Institute

Barbara Hansen

Chief Executive Officer

Oregon Hospice and Palliative Care Association

Data on physician-assisted death in long-term care are virtually nonexistent, Phillips said. Anecdotally, many nursing homes have policies against allowing physician-assisted death to occur onsite due to concerns about licensing and certification, among other issues. However, Phillips noted, data may not be collected on where the medication is taken. For example, California does not require “location of ingestion” to be reported.

Lynn said that challenges to physician aid-in-dying for the population in long-term care occur in three areas: (1) assessing cognitive competence, (2) ensuring voluntariness in potentially coercive situations, and (3) defining terminal illness (see Chapter 2 for more discussion on terminal illness). Regarding voluntariness, she said that many older individuals face impoverishment and the loss of their legacy as they dispose of their assets to become eligible for Medicaid and secure long-term services and supports. The potential for conflicts of interest with respect to nursing homes is also an issue that must be considered, Lynn emphasized. Almost all nursing homes are either for-profit (and therefore must pay their shareholders) or owned by a city, county, state, or other community, which are often financially strapped. Regarding cognitive abilities, Phillips said that between 50 and 70 percent of residents in long-stay nursing homes and assisted living facilities have documented dementia (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2016), and the level of cognitive impairment in those settings is thought to be even higher. On the other hand, the rates of dementia and cognitive impairment in home- and community-based services settings for long-term care are not known, she said.

Speaking about the barriers to accessing physician-assisted death for individuals in long-term care, Barbara Hansen, the chief executive officer of the Oregon Hospice and Palliative Care Association and the executive director of the Washington State Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, said that individuals who lack an attending physician or family or

friends who can serve or are willing to serve as witnesses find it difficult to pursue this type of death. Faith-based providers of long-term services and supports often do not allow physicians to participate, and for some residents in nursing homes, lack of mental capacity can be a barrier. Waiting too long and losing the capacity to self-medicate can be a barrier, as can the fact that most long-term care facilities do not allow the practice to take place onsite.

Phillips emphasized that the waiting list for many Medicaid-covered long-term care sites is quite long and that for every opening in subsidized senior housing, there are 10 seniors waiting; most will die before they are accepted. Combined with the financial challenges, these factors have the potential to create subtle—and not-so-subtle—pressures on older individuals to consider physician-assisted death. Additionally, many older people and their families have not discussed among themselves or with their health care providers the full range of options for addressing symptoms, managing the end of life, or developing care plans that fully reflect the individual’s wishes. Lynn said that a national dialogue and action are needed to support older individuals and their long-term care needs. Society does not care about this part of life and chooses not to talk about it, she said, even though the majority of people will go through this part of life.

To illustrate the range of issues and concerns specific to physician-assisted death, Lynn read a statement from the American Geriatrics Society in its amicus briefs for the Vacco v. Quill1 and Washington v. Glucksberg2 cases:

Most elderly persons experience serious and progressive illness for extended periods before death and need significant social, financial, and medical supports. These resources too often are not available. . . . By collaborating in causing early deaths . . . geriatricians would become complicit in a social policy which effectively conserves community resources by eliminating those who need services. By refusing . . . because a patient’s relative poverty and disadvantaged social situation is seen as coercive, geriatricians would condemn their patients, and themselves, to live through the patients’ undesired difficulties for the time remaining. . . . Elderly and frail persons would be put at risk [with physician-assisted death being available], yet their interests and concerns have not been adequately addressed in the public discussion. p. 491. (Schmitz et al., 1997, pp. 491–499)

While long-term care is getting some attention, primarily because of the managed Medicaid aspects, Phillips said, there are numerous research

___________________

1Vacco v. Quill, 521 U.S. 793 (1997).

2Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702 (1997).

and policy gaps in understanding how this population views physician-assisted death and their interest in or access to this option. Phillips noted that the current focus for physician-assisted death has been for younger people with more predictable courses of disease, such as with cancer or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and that little, if any, attention is being paid to the oldest who are grappling with frailty and lack of available support systems and care. Phillips questioned whether the focus should be on how to improve palliative care in the long-term care setting, instead of on physician-assisted death.

Lynn listed a number of research questions relevant to long-term care and physician-assisted death, including

- What are the current practices in long-term care settings regarding physician-assisted death in locations where it is legal?

- What are the financial, emotional, and other pressures being faced by older individuals using long-term services and supports, and how do they affect considerations of physician-assisted death?

- What are the potential and realized conflicts of ethics and values for providers of long-term care?

- Who will sponsor the research that is needed?

Hansen offered a list of topics for potential future research regarding the impact of physician-assisted death:

- Do any patients complete physician-assisted death because symptoms are not being managed?

- Is there a difference in the grief process for survivors of a person who completed physician-assisted death versus survivors of a person who died a natural death?

- How does caring for a person who completed physician-assisted death affect health care providers in the long term? Does it contribute to more or less “burnout”?

- How does the impact of physician-assisted death on families and health care providers compare to the effects when patients use other means of self-inflicted death?

- What is the impact on patients and families if their hospice program has a policy that does not allow their staff to be present in the home when the patient takes the medication?

HOSPICE AND PALLIATIVE CARE

Citing data from the Oregon Public Health Division, Hansen said that as of 2016, nearly 90 percent of patients using physician-assisted death were enrolled in hospice, and the great majority of deaths under Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act took place in the hospice patient’s home (Oregon Health Authority, 2017).

Experiences and Policies

Workshop speakers described a variety of experiences with physician-assisted death in hospice and palliative care and detailed a range of policies developed by their institutions.

Stephanie Harman

Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine and

Clinical Chief of Palliative Care

Stanford University School of Medicine

When Stanford Medicine deliberated as an institution about how it would participate in California’s new medical aid-in-dying law, the process was led by the institution’s ethics department, said Stephanie Harman, a clinical associate professor of medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine and the clinical chief of palliative care. This process included 20 town hall meetings which provided a broad perspective on what the medical staff thought about physician-assisted death as well as on the role that palliative care should be playing from an institutional perspective. Clinicians who were supportive of the legislation but did not want to be involved in the process thought that palliative care physicians should be the sole providers of the prescriptions, a position with which Harman and her colleagues in palliative care disagreed. Harman explained that she and her colleagues did not want to be in the official position of prescribing lethal medications but rather wanted to strive to facilitate dialogue in the process.

Clinicians who were opposed to the law said that if Stanford Medicine was going to participate, there should be as many safeguards put into place as possible. A third group wanted to keep others from being involved in the decision as a means of maintaining their relationship with their patients. In their view, no policy was needed. The one thing that everyone agreed on, Harman said, was that patients requesting physician-assisted death have palliative care needs.

When Stanford implemented its policy on physician-assisted death, it added a few features that were not required in the law. For example, Stanford’s policy requires an ethics consultation following the initial

patient request. The ethics consultants provide support and resources, serve as navigators, and answer questions. They also help the patient connect to social workers who can direct the patient to a physician who is willing to prescribe in the case where the patient’s usual clinician will not. Stanford’s policy also requests completion of an advance directive and physician order for life-sustaining treatment forms if those have not already been completed.

Palliative care participated fully in the process of developing these institutional policies, Harman said, and is a required part of the physician-assisted death process at Stanford. Palliative care physicians who choose to participate take on the role of the willing consulting physician, she said, which involves both serving as the consulting physician and helping the patient explore any available options that may not have been discussed previously (palliative care physicians can also decline to serve as the consulting physician, as per the law). Palliative care also conducts a physical, social, emotional, and spiritual assessment of the patient, and it provides a wide range of services to both the patient and family members.

Harman said that the institution had to develop an overall approach for triaging patients who wanted to access physician-assisted death. There is a sense of urgency for scheduling these appointments, not just for the patients but also for attending physicians. At the same time, she said, there was a concern as to whether that urgency should trump the needs of patients who are coming into clinic for acute symptom management. She also said that many patients are seeking aggressive, innovative treatments that may be available to them through clinical trials and which may extend their life beyond a 6-month prognosis, while also seeking physician-assisted death as a backup plan. Reconciling those desires for continued disease-directed care and the option of physician-assisted death has been challenging, Harman said. She said that the key lesson thus far has been to elicit all voices in the conversations about physician-assisted death, and to listen. As a final note, she said that by codifying palliative care into Stanford’s physician-assisted death process, palliative care has become more widely recognized across the institution as a resource and source of support for clinicians, patients, and families going through a very difficult experience.

Gary Pasternak

Medical Director

Mission Hospice and Home Care

Saying that his views have been shaped by his 20 years of experience as a practicing palliative care and hospice physician, most of it at a small, nonprofit, community-based hospice in San Mateo, California,

Gary Pasternak, the medical director at Mission Hospice and Home Care, said that he has a fairly neutral view about physician-assisted death and, like many palliative care physicians, believes that the focus of efforts should be on the broader provision of palliative care.

When California passed the End of Life Options Act (EOLOA), he said, his organization responded quickly to the new law, holding several months of brown bag discussions, forums, and meetings to educate itself about the law and find out how staff felt about it. An interdisciplinary committee that included non-clinical staff took the feedback from these activities and wrote a policy defining what EOLOA meant to the agency and its staff members, knowing it would be a work in progress. An important part of developing this policy was to establish ongoing support groups for staff, facilitated by the spiritual care and social work staff.

The essentials of the resulting policy included the decision for the agency to opt in and meet patients where they are, but to never suggest or recommend EOLOA to patients. The policy states that only one of the physicians (either the consulting or attending physician) involved in a patient’s request for physician-assisted death can come from the hospice and that multidisciplinary involvement would always be offered and encouraged. Any staff member can refuse to participate without any repercussions, and a patient having been admitted to the hospice does not obligate the agency to provide this end-of-life option to the patient. A counselor is available for any team member requesting it. The agency provides ongoing education, evaluation, and support.

The organization had its first request for physician-assisted death within 24 hours of the law going into effect, Pasternak said, and it was one of his own patients. Pasternak said that he decided to assist his patient with her request after seeking mentoring and counseling from an Oregon physician who had many years of experience. Pasternak said that after multiple meetings with the patient, a 93-year-old lawyer with lung cancer who was failing rapidly, and the patient’s family, he had no question in his mind that she was clearly a candidate for the procedure. He was present for her ingestion of the lethal medication, and he noted that he “found the experience compelling in its peacefulness, the sense of relief and completion for the family, and in the remarkable value of the presence of the hospice staff.”

Based on this and subsequent experiences, Pasternak said, it is his hospice’s practice to have as many team members present as the patient and family will allow, but almost always a physician and a nurse. No family has refused this offer of assistance and support, and almost every family welcomes the presence of hospice staff. He said he feels that this

is one of the best aspects of the practice that he and his colleagues have developed in that they do not just prescribe the medication, but they also see the process through.

So far, he said, his organization has served some 40 patients, gaining a great deal of experience in the process. That experience has taught Pasternak that hospice, with its whole-person and family approach to end-of-life care, is uniquely situated to be part of these dying experiences. Quoting a member of his staff, one of the EOLOA group facilitators, he said, “Engaging with EOLOA has had a profound impact on our staff. The common response is one of awe, along with humility and gratitude for the privilege of witnessing such a peaceful passage.”

Pasternak then described two different trajectories and levels of involvement with the hospice and requests for physician-assisted death. In one case the patient, a 97-year-old woman who was the matriarch of a large family and a strong advocate for the California law, began talking about physician-assisted death as an option about a year before the law was passed. She had lived in a large assisted-living facility for many years, and when she was diagnosed with a terminal illness, her goals of care were clear, and her primary care doctor honored her request for EOLOA and agreed to be the prescribing physician. One week before her final day, her assisted living facility had developed a policy that allowed this to occur at the facility. On her final day, she had each member of her family come into her room for one last goodbye and to provide one last bit of advice. There were tears mixed with laughter as they all gathered, Pasternak recalled, and she passed away peacefully. One of her daughters later wrote a note to Pasternak and his colleagues expressing her family’s deep gratitude.

Another patient, a 72-year-old woman with ovarian cancer, was interested in getting the process of requesting physician-assisted death going quickly as her health was failing and she was concerned about the care options. However, with time she became more ambivalent about dying and about taking the medications. Her family did not support her interest in pursuing assisted death. Pasternak said that the patient wanted him to decide for her, and it became one of her biggest burdens that she had this choice. When she became too frail to remain in her home, she was transferred to the agency’s hospice house, and the comprehensive application of palliative care in a multidisciplinary hospice setting met her needs. She never took the medication. Pasternak said, “I think the simple and constant presence of the entire staff basically supported her as a person beyond the confines of her illness, so her illness and her suffering were not what totally defined her.”

One of his main concerns with physician-assisted death, he said,

is that it may be contributing somehow to premature closure. For this patient, intensive palliative care was extremely helpful, and she had a very peaceful death without intractable symptoms.

Steven Pantilat

Kates-Burnard and Hellman Distinguished Professor in Palliative Care

University of California, San Francisco

The approach that the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), is taking in response to California’s EOLOA, said Steven Pantilat, a professor of medicine, the Kates-Burnard and Hellman Distinguished Professor in Palliative Care, and the director of the Palliative Care Program and Palliative Care Quality Network at UCSF, is that people who request the EOLOA option need palliative care. At the same time, he said, he and his colleagues feel strongly that palliative care is not to be equated with the end of life. In fact, he said, the palliative care team has worked assiduously over many years to disconnect palliative care from the end of life and move it upstream.

After extensive discussions, Pantilat continued, his team decided that it did not want everyone requesting assisted death to get a mandatory referral to palliative care. Most, but not all, of the palliative care physicians on the team did decide to be willing to serve as the consulting physician for most patients and as the prescribing physician for longstanding patients. A consulting physician’s focus is on confirming a prognosis of limited time, discussing options with the patient and family, and determining if the patient has the capacity to make the decisions. However, it was clear, Pantilat said, that nobody wanted to be the “go-to” physician for physician-assisted death requests.

As UCSF developed its institution-wide policy, it started from the premise that, as a public institution, it would participate in the options provided in the law. Developing the policy was a lengthy process in which a great deal of input was solicited, with the underlying knowledge that the final policy would be a model for the state. Pantilat said that he and his colleagues never assumed they were creating a perfect policy, only that other institutions in the state would look to UCSF.

One aspect of UCSF’s policy is that participating in EOLOA requires viewing an educational slide set and passing a test to receive a designated medical staff privilege. One of the two physicians participating in a physician-assisted death request must have that privilege. UCSF’s policy also mandates a psychiatric referral so that potential mental health issues in the candidate population are not overlooked. Pantilat acknowledged that this makes an already burdensome process more so, and in some

cases, when it is clear that the patient and family support the decision strongly, the referral requirement is waived. At UCSF, social workers are the point of contact for information, but they are not navigators because they do not walk patients through the entire process.

UCSF’s experience has been that few physicians have agreed to participate in the program, and the institution does not keep a list of those physicians who are willing. Nearly all patients interested in physician-assisted death are enrolled in hospice, he said. In general, the process is difficult for patients, especially for those with neurologic conditions. From Pantilat’s experience as a palliative care physician who has worked with ALS patients, he said that by the time most patients with ALS have a clear 6-month prognosis, they are not able to take the medication. He also said that pharmacies and pharmacists are crucial partners in the process and that it is vital to ask questions of patients and listen carefully to their answers about why they are bringing this up now and what they worry about most in the days ahead.

Pantilat recommended that institutions developing policies in response to physician-assisted death laws should prioritize establishing a clear process and support for patients, families, and clinicians. Partnering with hospice and with pharmacists is also important, as is identifying physicians who are willing to prescribe. In his opinion, he said, the best scenario would be to identify two physicians, supported by an interdisciplinary team, to do the prescribing and take referrals, but his organization has not achieved that yet. It is important, he added, to trust the clinicians who agree to participate, while also looking for potential abuses that might arise if all prescribing is concentrated among a few physicians who might look at prognosis or capacity differently. Pantilat said that identifying two physicians to play the primary role in all physician-assisted death requests would require caution but would likely provide better access for patients and families.

Pantilat also suggested that all patients requesting physician-assisted death be referred to palliative care. He said that one benefit of EOLOA has been that people are being referred more often to UCSF’s palliative care service. He described the experience of a 94-year-old patient who was interested in assisted death but whose daughter did not support that option. The woman received palliative care and was prescribed the lethal medications but died peacefully before the date she had set to take the medications. Pantilat said that the EOLOA experience did lead this patient to get the care she really needed.

Timothy Quill

Thomas and Georgia Gosnell Distinguished Professor in Palliative Care

University of Rochester

Timothy Quill, the Thomas and Georgia Gosnell Distinguished Professor in Palliative Care at the University of Rochester Medical Center, said that fundamental access to health care—meaning the full range of disease-directed treatment as well as adequate palliative care, decision-making assistance, and sometimes assistance with end-of-life decision making—is essential. Hospice fits into health care as both a philosophy of care and as a medical benefit, he said, but he cautioned against telling dying individuals that hospice is 100 percent effective at relieving suffering. “We have to learn how to acknowledge the exception,” he said. “Sometimes the exceptions are uncontrolled physical symptoms, for example, pain and shortness of breath. Other times they are unrelieved psychosocial, existential, and spiritual suffering.”

Awareness of last-resort options is important, Quill said, because many people have seen harsh deaths and worry that could happen to them. For some people, knowing what the options are for ending life gives them a sense of reassurance; most often the options are not exercised even when openly available. Quill mentioned data from Oregon showing that one in six individuals in palliative care or hospice talk about life-ending options with their families, though he guessed that even more individuals probably think about these options but do not raise them with their families. One in 50 talks about these issues with their physician, he said, and in Oregon 1 in every 300 deaths of people enrolled in palliative care or hospice is from medical aid-in-dying (Tolle et al., 2004).

Quill said that it is important to try to ensure that all palliative care alternatives have been examined and exhausted and then, if necessary, to look for the best ways to respond to a patient requesting aid-in-dying that respects the values of the major participants. It is also important to ensure that a patient has full informed consent and active participation of close family members. Quill listed the range of last-resort options, roughly ordered by how much societal agreement exists about their acceptability:

- accelerating opioids to sedation for pain or dyspnea

- stopping life-sustaining therapies

- voluntarily stopping eating and drinking

- palliative sedation, potentially to the point of unconsciousness

- physician-assisted death

- voluntary active euthanasia

Quill said that voluntarily stopping eating and drinking requires tremendous discipline and usually takes 1 to 2 weeks to result in death. This option is probably legal, he said, though it has never been tested in the courts. Providing palliative sedation to the point of unconsciousness can also take days to 1 week or more to result in death, usually from dehydration or a complication of the sedation, but the patient is generally unaware of the suffering.

Quill said that providing palliative sedation to the point of unconsciousness varies widely among palliative care and hospice practices. There are palliative care programs, he said, where patients are frequently heavily sedated at the very end, and there are places that almost never provide sedation. He said he believes that this variation in practice is more a reflection of physicians’ values than of the values of the patient. Quill suggested that the same kinds of safeguards that are applied to physician aid-in-dying cases should be considered for palliative sedation. He also suggested that the risks cited for physician-assisted death are present to a greater or lesser degree for the other last-resort options as well.

In New York, where physician-assisted death is not legal, there are organizations that support more potentially life-ending options, which raises the question of whether hospice or palliative care clinicians should tell patients who are interested in these options about those organizations or withhold that information. These organizations do advocacy work and provide information and counseling. They also often provide a presence for individuals who are considering a last-resort option.

In closing, Quill emphasized the importance of information being available to patients about the full range of last-resort options, including what their own physicians legally and personally can and cannot do.

Studies and Informal Surveys of Hospice and Palliative Care Programs and Physician-Assisted Death

Courtney Campbell

Hundere Professor of Religion and Culture

Oregon State University

Courtney Campbell has conducted research on hospice and palliative care program policies regarding physician-assisted death in Oregon (Campbell and Cox, 2010) and Washington (Campbell and Black, 2014). Some hospice programs—more than 35 percent in Oregon and 20 percent in Washington—identified as non-participating, he said, largely because of religious considerations, though some non-religious programs have decided that physician-assisted death was outside of the scope of hospice care as they defined it. No program that identified itself

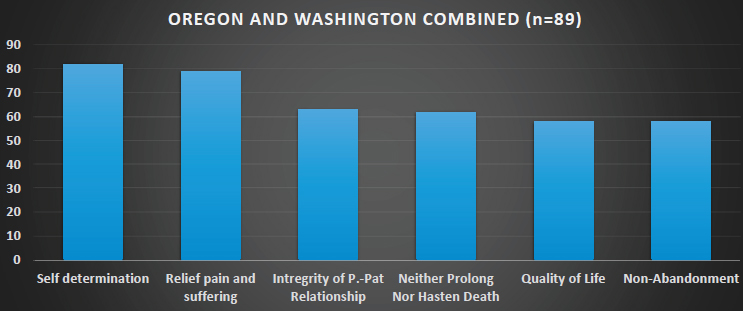

NOTE: P.-Pat Relationship = physician–patient relationship.

SOURCE: Campbell presentation, February 12, 2018.

as non-participating indicated that it would discharge a patient from hospice care because that patient made a request or inquiry or had a conversation about physician-assisted death. A second group of hospice programs—approximately 30 percent in both states—were generally neutral on physician-assisted death and treated it as an issue between the physician and patient. The third group of hospice programs engaged in what they called “respectful participation.” These programs—nearly 35 percent in Oregon and 45 percent in Washington—said they respected patient choices and the integrity of the physician–patient relationship. They also respected the decisions of clinicians to not continue to provide care because of contentiousness or religious considerations.

Campbell also examined the values underlying these positions (see Figure 6-2). When hospices were questioned about the principles they relied on in crafting their physician-assisted death policies, patient self-determination was mentioned more than any other, while the value of neither prolonging nor hastening death—a pillar of hospice philosophy—ranked fourth. Non-abandonment was also an important consideration, though 55 of the 89 hospice programs in Oregon and Washington that Campbell examined prohibited hospice staff from being present at the time of ingestion and death.

Ethnocultural Disparities and Physician-Assisted Death

Jeffrey Berger

Chief, Division of Palliative Medicine and Bioethics

New York University Winthrop Hospital

In his presentation, Jeffrey Berger, the chief of the Division of Palliative Medicine and Bioethics at the New York University Winthrop Hospital and a professor of medicine at the Stony Brook University School of Medicine, said that physician-assisted death is disproportionately a concern of well-educated whites, an observation that he believes should stimulate some questions. At the same time, he said, there are disparities and distrust in palliative medicine, as there are in health care in general. These disparities and distrust, he added, have well-founded historical roots in both explicit and implicit racially based discriminatory practices (Williams and Wyatt, 2015).

In palliative care, Berger said, the literature suggests that African Americans are more likely than whites to have a preference for more life-sustaining therapies regardless of prognosis, and African Americans are less likely to assign a health care proxy or complete a living will out of concerns that these legal documents will be used against them in some fashion (Crawley et al., 2000; Johnson, 2013). African Americans are also less likely than whites to use hospice care and more likely to leave hospice care once they have begun using it. African Americans have less knowledge than whites about palliative care and are, because of spiritual and religious beliefs, less likely to embrace the goals of palliative care. African Americans also tend to have poorer pain control options, with one study finding that people of color in general have less access to pain medications because the pharmacies in their communities tend to stock those medications less often than in white communities (Morrison et al., 2000).

Berger said that the literature disagrees on the reasons for these disparities (Lichtenstein et al., 1997; Loggers et al., 2009; Mack et al., 2010; Volandes et al., 2008; Wasserman et al., 2016; Welch et al., 2005). The reasons that various researchers have posited based on assorted studies include mistrust of the health care system, religious beliefs, health literacy differences, disparities in effective communication and care planning, and disparities between palliative and hospice care teams and minority populations. These studies, Berger said, are limited and offer an unclear consensus, with potential confounding by health literacy considerations. There is a need for improved methodologies to be used in these types of surveys.

One thing that Berger said she worries about is the potential that physician-assisted death has for stimulating greater suspicion and mistrust among underserved populations, leading to further disparities

in care. He noted that this is speculation, as there are no data on this matter. To promote evidence-based health and social policy, Berger recommended that these considerations should be studied in jurisdictions where physician-assisted death is permitted. He added that California, as a demographically diverse state, will provide an important source of data for answering questions about disparities in accessing not only physician-assisted death, but palliative care and hospice as well.

DISCUSSION

Vulnerable Populations

A workshop participant with experience as a palliative care nurse in Baltimore said she had felt uncomfortable when hearing in some presentations and workshop discussions that patients must be very persuasive in convincing their physician of the seriousness and legitimacy of their request for aid-in-dying. She said that she has seen that an already unequal power dynamic exists between patients from a vulnerable or minority population and their physician and that she is not surprised that few patients take this option, given the challenges of navigating the system as well as the need to persuade providers in multiple situations that this is the right approach for that individual patient. Quill agreed that the challenges facing vulnerable populations are significant and said that the challenges include the fact that a patient risks being labeled as suicidal by attempting to go through this process—a label that could have very negative consequences for the patient. Quill is struck by the tension surrounding the issue of whether every patient needs to hear that physician-assisted death is an option. He suggested that doing so could frighten many patients and dramatically increase distrust of the medical system. The challenge, he said, lies in determining how physicians can bring up physician-assisted death in a way that is acceptable to a patient and appropriate given their circumstances.

Barbara Koenig of UCSF reflected on the power dynamics inherent in the patient–physician relationship for regular medical care. For instance, are there levels of coercion related to pursuing aggressive cancer treatment? In terms of when to raise the topic of assisted death with a patient, Koenig suggested that possible “trigger” phrases from a patient, such as speaking of a fear of future suffering or requesting to know all of the options as the end of life nears, can indicate to a physician it is appropriate to discuss physician-assisted death.

A workshop participant asked about the recent Washington, DC, decision on physician-assisted death in light of a population and city government that is largely African American as well as concerns about

the legacy of health disparity. Berger said that he was not familiar with the determinations and the approval process in the District of Columbia and emphasized the need to understand the drivers of interest on both sides of the issue of physician-assisted death.

Christopher Kearney, the medical director for MedStar Health Palliative Medicine, said that he had been surprised that physician-assisted death was legalized in Washington, DC, and questioned whether the legalization would have been successful if the measure were voted on by ballot referendum as opposed to a city council vote. His experience as a physician in nearby Baltimore would indicate that there would not be support for such a law, he said. As MedStar has locations in Washington, DC, as well, the institution is facing the challenge of how to respond to the recent legalization of physician-assisted death. Kearney reported that MedStar has not made a decision yet as to the position the institution will take on physician-assisted death, but he said that the company has stated that no one should request aid-in-dying for lack of quality palliative care. He challenged workshop participants to consider a perhaps more useful requirement for hospice care for patients requesting aid-in-dying, as opposed to the current legal requirements for mental health evaluation.

Institutional Responses

Scott Halpern of the University of Pennsylvania asked whether, despite the relative unease of individual physicians in becoming the “go-to” physician for assisted-death referrals and prescriptions, it would not be the unambiguously right approach to have a few physicians conduct the process for patients all the time. Halpern suggested that having “go-to” physicians who are well supported and trained in the nuances of physician-assisted death would build much needed expertise and could result in a better experience for patients and families. In addition, if physicians were willing to be involved in assisted-death requests for patients some of the time, then they must not have a conscientious objection to the practice, in which case it could be a better allocation of resources to have a few physicians be involved in all the assisted-death requests at a particular institution. He reflected on his experience as a critical care physician in the United States during the Ebola epidemic. Because the U.S. cases of Ebola were rare, it did not make sense for every physician at his hospital to be trained in the appropriate precautions, he said, so a few physicians volunteered to take on this training for the institution. Pantilat responded that there are physicians willing to be the “go-to” in his area of California, but none of them are at his institution. UCSF physicians do sometimes refer patients to the few physicians in the area who participate in assisted deaths frequently. Pantilat suggested that in order for a few physicians

to succeed at this they would need the support of a team—including a social worker, nurse, and chaplain working together. Pantilat also suggested that some of the unease among physicians may be related to the newness of physician-assisted death, and he suggested that over time physicians may become more comfortable with it. Harman responded that at Stanford there are physicians who are willing to prescribe for their own patients as well as willing to prescribe for other physicians’ patients. While these physicians are not known as the “go-to” doctors, those who do have experience as prescribers serve as resources to guide physicians new to the process.

Professional Societies

Workshop participant Christopher Kearney of MedStar Health asked whether it would be beneficial for the United States to follow the example of the Dutch medical professional societies that have created specialized panels surrounding aid-in-dying in order to deploy standards in this process. He asked why U.S. medical societies have been largely silent or unengaged in the issue of aid-in-dying. In a similar vein, Rebecca Spence, the ethics counsel for the American Society of Clinical Oncology, asked the participants to comment on the role of professional societies in addressing physician-assisted death. Lynn responded that on the broader issue of supporting long-term services and supports, few of the professional societies have spoken up in support of these issues. Regarding physician-assisted death policies, Lynn said, there could be efforts by professional associations into developing a relevant policy by receiving a wide range of input and having extensive discussions (as discussed by several representatives of hospital and hospice systems in Chapter 5).

Concerns Regarding Underfunded Long-Term Services and Supports

Lynn said—and was echoed by Ron Motley, a geriatric psychologist in northern Virginia, and by John Kelly from Not Dead Yet—there are looming concerns about nursing home, home care, and long-term care costs for our society and its older and disabled members.

Lynn said that a way forward for the United States could be to move resources from the overfunded medical care side to the underfunded long-term services and supports side, but that would be dangerous because it would risk losing the open-ended entitlement for medical care in this country. She indicated that returning some control over these expenditures to geographic localities could be part of a solution and said that it is an approach that almost every other country takes. She cautioned that in this scenario there would still be limits, of course, as it is estimated to

cost $250,000 to support an individual with 24-hour care at home for 1 year, and therefore it is unlikely that everyone who could benefit from this level of care would be able to receive it (Lynn, 2016). The country has not yet had serious discussions about these costs and what the limits are, Lynn said, but the conversation should be forced before the baby boomer generation retires en masse.

REFERENCES

Anthony, S., A. Traub, S. Lewis, C. Mann, A. Kruse, M. H. Soper, and S. A. Somers. 2017. Strengthening Medicaid long-term services and supports in an evolving policy environment: A toolkit for states. Hamilton, NJ: Center for Health Care Strategies.

Bradley, E. H., and L. A. Taylor. 2013. The American health care paradox: Why spending more is getting us less. New York: PublicAffairs.

Campbell, C. S., and M. A. Black. 2014. Dignity, death, and dilemmas: A study of Washington hospices and physician-assisted death. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 47(1):137–153.

Campbell, C. S., and J. C. Cox. 2010. Hospice and physician-assisted death: Collaboration, compliance, and complicity. Hastings Center Report 40(5):26–35.

Crawley, L., R. Payne, J. Bolden, T. Payne, P. Washington, and S. Williams. 2000. Palliative and end-of-life care in the African American community. JAMA 284(19):2518–2521.

Family Caregiver Alliance. 2015. Selected long-term care statistics. https://www.caregiver.org/selected-long-term-care-statistics (accessed April 24, 2018).

Favreault, M., and J. Dey. 2016. Long-term services and supports for older Americans: Risks and financing research brief. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Genworth Financial. 2016. Genworth 2016 annual cost of care study: Costs continue to rise, particularly for services in home. Richmond, VA: Genworth Financial.

Harris-Kojetin, L., M. Sengupta, E. Park-Lee, E. Valverde, C. Caffrey, V. Rome, and J. Lendon. 2016. Long-term care providers and services users in the United States: Data from the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers, 2013–2014. Vital and Health Statistics 3(38). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_03/sr03_038.pdf (accessed June 21, 2018).

Johnson, K. S. 2013. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. Journal of Palliative Medicine 16(11):1329–1334.

Lichtenstein, R. L., K. H. Alcser, A. D. Corning, J. G. Bachman, and D. J. Doukas. 1997. Black/white differences in attitudes toward physician-assisted suicide. Journal of the National Medical Association 89(2):125–133.

Loggers, E. T., P. K. Maciejewski, E. Paulk, S. DeSanto-Madeya, M. Nilsson, K. Viswanath, A. A. Wright, T. A. Balboni, J. Temel, H. Stieglitz, S. Block, and H. G. Prigerson. 2009. Racial differences in predictors of intensive end-of-life care in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 27(33):5559–5564.

Lynn, J. 2016. Medicaring communities: Getting what we want and need in frail old age at an affordable cost. Washington, DC: Altarum Institute.

Mack, J. W., M. E. Paulk, K. Viswanath, and H. G. Prigerson. 2010. Racial disparities in the outcomes of communication on medical care received near death. Archives of Internal Medicine 170(17):1533–1540.

Morrison, R. S., S. Wallenstein, D. K. Natale, R. S. Senzel, and L.-L. Huang. 2000. “We don’t carry that”—failure of pharmacies in predominantly nonwhite neighborhoods to stock opioid analgesics. New England Journal of Medicine 342(14):1023–1026.

Morrissey, M. 2016. The state of American retirement: How 401(k)s have failed most American workers. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute.

Oregon Health Authority. 2017. Oregon Death with Dignity Act 2017 data summary. Salem: Oregon Health Authority.

Parikh, R. B., A. Montgomery, and J. Lynn. 2015. The Older Americans Act at 50—Community-based care in a value-driven era. New England Journal of Medicine 373(5):399–401.

Pennsylvania Health Care Association. n.d. The need for long-term care continues to grow. https://www.phca.org/for-consumers/research-data/long-term-and-post-acute-care-trends-and-statistics (accessed April 24, 2018).

Schmitz, J. E., M. Delrahim, J. H. Pickering, and A. M. Stoeppelwerth. 1997. Brief of the American Geriatrics Society as amicus curiae urging reversal of the judgments below: Vacco v. Quill. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (45)4:491–499.

Tolle, S. W., V. R. Tilden, L. L. Drach, E. K. Fromme, N. A. Perrin, and K. Hedberg. 2004. Characteristics and proportion of dying Oregonians who personally consider physician-assisted suicide. Journal of Clinical Ethics 15(2):111–118.

Volandes, A. E., M. Paasche-Orlow, M. R. Gillick, E. F. Cook, S. Shaykevich, E. D. Abbo, and L. Lehmann. 2008. Health literacy not race predicts end-of-life care preferences. Journal of Palliative Medicine 11(5):754–762.

Wasserman, J., J. M. Clair, and F. J. Ritchey. 2016. Racial differences in attitudes toward euthanasia. OMEGA–Journal of Death and Dying 52(3):263–287.

Welch, L. C., J. M. Teno, and V. Mor. 2005. End-of-life care in black and white: Race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 53(7):1145–1153.

Williams, D. R., and R. Wyatt. 2015. Racial bias in health care and health: Challenges and opportunities. JAMA 314(6):555–556.