SAFEGUARDS

Thaddeus Pope

Director, Health Law Institute

Mitchell Hamline School of Law

At the time of the workshop, five states (California, Colorado, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington) and the District of Columbia had approved medical aid-in-dying laws,1 and more than half of the remaining states had

___________________

1 A 2009 Montana Supreme Court decision ruled that state law protects Montana physicians from prosecution for helping terminally ill patients die. See Baxter v. Montana, 224 P.3d 1211 (2009). This information was added after prepublication release. Therefore, no legislation exists in Montana to serve as the basis for a discussion of safeguards in that state. In addition, Hawaii legalized physician-assisted death in April 2018, after this workshop took place.

bills under consideration to affirmatively legalize medical aid-in-dying, said Thaddeus Pope, the director of the Health Law Institute and a professor of law at the Mitchell Hamline School of Law. Existing and proposed statutes include the same safeguard provisions included in the initial Oregon law. The safeguards are (1) a mental health evaluation to evaluate impaired judgment, (2) terminal illness, (3) self-administration, (4) limitation to adults, (5) capacity (i.e., no advance directives), (6) waiting period, and (7) certification by two physicians (i.e., no nurse practitioners). Pope addressed the issue of whether these seven safeguards are too weak or too strong based on the available data. He stressed that he was not making an argument pro or con, but rather an objective presentation of how institutions and legislatures are approaching safeguards surrounding medical aid-in-dying.

In terms of the current safeguards being potentially too weak, Pope said he only had one good example, and that involves the mental health evaluation for determining impaired judgment. The problem with that, he explained, rests with how individuals are screened for impaired judgment resulting from a mental disorder. While the current and proposed laws all call for physicians to refer individuals to a mental health specialist if they suspect there is a mental health issue, that referral happens rarely (Oregon Health Authority, 2018). Less than 5 percent of the patients who received prescriptions through medical aid-in-dying laws were referred for a mental health screening (Oregon Health Authority, 2018), and that number has been decreasing over time.

Many of those who argue against medical aid-in-dying believe that this referral rate is too low. In response, Pope said, some institutions now require a mental health screening for everyone who seeks to receive a prescription for lethal medication, and some jurisdictions have sought to include mandatory screening in their laws. Scotland included mandatory screening in its proposed law, which did not pass, and Belgian law includes mandatory screening for some categories, such as for individuals who are not terminally ill and for mature minors (Boring, 2014; Scottish Parliament, 2010). Pope said that he knew of no evidence to suggest that individuals with impaired judgment were accessing lethal prescriptions when they should not have been able to do so under the law, but it is an area worthy of additional research.

Are the safeguards too strong? Pope said that there are six examples that suggest the eligibility requirements for access to physician-assisted death may indeed be too stringent. The first example is the requirement that a patient have a terminal and irreversible illness that will cause death within 6 months. There are many people who, at least in their own judgment and estimation, are suffering unbearably but are not terminally ill, he said, and such individuals would be excluded from access in the

United States in the absence of a terminal illness. Even the American College of Physicians, which is opposed to what it calls “physician-assisted suicide,” admits that it is arbitrary to limit the option to people who are terminally ill (Snyder Sulmasy and Mueller, 2017).

Victoria, Australia, recently passed a medical aid-in-dying law that extends the time frame for prognosis to 12 months for neurodegenerative disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The premier of Victoria noted in a tweet that this law is the most conservative, voluntary assisted dying model ever proposed or implemented in the world.2 On the other hand, Pope said, Canada has dropped an exact time limit and instead requires that death be “reasonably predictable.” There is no time limit on access in laws governing assisted death in Belgium, Luxembourg, or the Netherlands.

Another area where the current U.S. state laws may be too strict, said Pope, is their requirement for self-administration of the lethal medication. This requirement is designed to help assure voluntariness, Pope explained, but some individuals lose the ability to self-ingest the medication. In addition, some people have complications from self-ingestion, as shown by the 3 to 6 percent complication rate noted in the latest data from Oregon (Oregon Health Authority, 2018). Pope added that the complication rate may rise as the practice moves away from using secobarbital to newer medications that do not have the same track record (Oregon Health Authority, 2018). Belgium, Canada, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands avoid this potential problem by allowing clinicians to administer lethal medications. Victoria’s new law allows physician administration, but only in the case where a patient is physically incapable of self-administration or digestion.

The third safeguard Pope discussed was the requirement that access to physician-assisted death be limited to adults, which is designed to assure that the decision is voluntary and informed. However, many U.S. states allow minors to make other life-and-death health care decisions about life-sustaining treatment. Canada, which currently restricts medical aid-in-dying to adults, is considering whether to extend the law to mature minors (Gerein, 2017). Current laws in Belgium and the Netherlands allow minors to access assisted death.

Pope then considered the safeguard concerning capacity that requires the request be made directly by the individual and not by advance directive. The problem here, he said, is that by the time someone with dementia is terminally ill, that person will not have the capacity to request the procedure. He noted that the Alaska state Supreme Court said it would

___________________

2 Tweet from @DanielAndrewsMP on November 21, 2017, https://twitter.com/danielandrewsmp/status/933201795106594816?lang=en (accessed March 25, 2018).

be unconstitutional to allow medical aid-in-dying contemporaneously, but to not allow it by advanced decision.3 Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands allow consent by advance directive, and Canada is currently considering this expansion as well.

The fifth provision that may be too strict, according to Pope, is the requirement that multiple requests for the lethal medication be separated by a specified waiting period. This requirement seems to be a good idea in that it ensures that the request is enduring, settled, and deliberative, but many, Pope said, have written that it imposes an undue burden on some patients (Ouellette, 2017). Victoria addresses this problem in its new law by allowing the waiting period to be waived if there is a certification that the death is likely to occur before the expiration of the waiting period.

The final requirement Pope considered was the provision that requires certification by both an attending and a consulting physician who must each be an M.D. or a D.O. licensed in the state. This requirement can cause a serious access problem when it comes to finding two available and willing physicians, Pope said, adding that there is a growing literature on whether nurse practitioners should be included in the list of eligible providers, just as they are now with physician order for life-sustaining treatment forms (Stokes, 2017). Canada allows nurse practitioners to sign the certification form for requests for assisted death, and several states are considering bills to allow that as well.

ACCESS

Courtney Campbell

Hundere Professor of Religion and Culture

Oregon State University

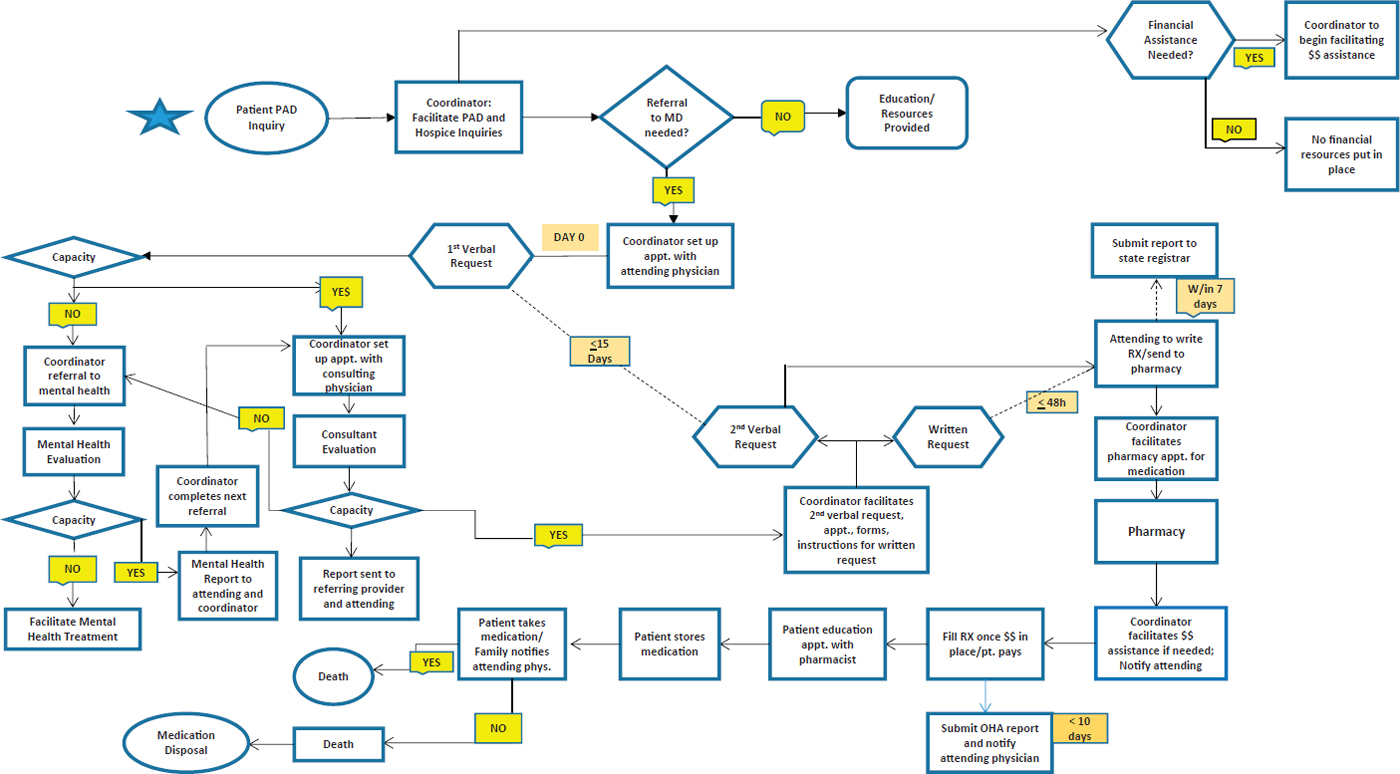

Regarding access, Courtney Campbell, the Hundere Professor of Religion and Culture at Oregon State University, said that another issue has become the cost of the lethal medication. The preferred medication, secobarbital, now costs approximately $3,000–$5,000 for a lethal dose (Death with Dignity National Center, n.d.). Other less expensive drug combinations have been introduced, but these have some additional side effects. Another access-related issue arises from the complexity of the bureaucratic process that a patient must go through to receive a prescription under the current laws (see Figure 5-1), which Campbell said is difficult for both patient and physician to navigate.

Campbell said that most of the issues Pope discussed are being looked at in other countries and that they are not new issues. “They were pres-

___________________

3Sampson v. Alaska, 31 P.3d 88. (2001).

NOTE: MD = medical doctor; PAD = physician-assisted death; RX = prescription.

SOURCE: Campbell presentation, February 12, 2018. Created through collaboration with Thomas Steele, M.D.

ent in the Oregon discussion of 1993 to 1994,” he said. Campbell pointed out that in 2017, the Oregon legislature considered, but did not pass, an amendment to the current law that would have allowed a patient who had executed a lawful advance directive to identify an agent, called an attorney-in-fact, who could collect and administer the lethal medication if the patient had already received the prescription but had not yet received the medication.4 Campbell suggested it is worthwhile to consider why that kind of proposed advance directive process was debated and refused in 1993, 1994, and 2017.

In his opinion, he said, if the discussion about safeguards were to be focused primarily on the best interest of patients, rather than those of physicians and pharmacists, the answers to these questions might be different. Safeguards are built into the laws to ensure that physicians or pharmacists would be immune from prosecution, Campbell explained. This way, he said, physicians and pharmacists do not have to make quality-of-life assessments about extraordinary suffering or directly administer a lethal agent into the patient’s body, but simply are responsible for determinations of capacity. Similarly, because the Oregon law imposes no legal duty on any health care professional to participate in prescribing lethal medication, the provision acts as a safeguard against involuntary participation by physicians or pharmacists, who can choose to participate or not with moral integrity. Campbell indicated that the safeguards were also written into the laws to assure the public that the process would not be abused and to prevent the unregulated incidents that had received so much publicity as a result of Jack Kevorkian’s activities.

One problem with the current regulations in Oregon, Campbell said, is that they do not specify an implementation procedure, that is, what happens from the time the prescription is written until the patient’s death. According to Campbell, there is some level of unknown in at least 50 percent of the Oregon deaths that are reported (Hedberg and New, 2017). The unknowns include whether there was a provider present at the time of medication ingestion, the duration between ingestion and unconsciousness, and the duration between ingestion and death.

However, the law does not preclude providers in different environments, such as the hospice setting, from developing best practices to help address some of these concerns. For example, between 75 and 90 percent of the patients who use physician-assisted death in California, Colorado, Oregon, and Washington (the percentage varies by state) are enrolled in hospice (California Department of Public Health, 2017; Colorado Department of Public Health and Education, 2018; Oregon Health Authority,

___________________

4 79th Oregon Legislative Assembly, SB 893, “A Bill for an Act” to amend ORS 127.800, 2017.

2018; Washington State Department of Health, 2017). Campbell explained that hospice becomes an important safeguard for many of the issues that might cause concern if there is a one-on-one relationship between the physician and patient. Hospice care is based on a team philosophy, and hospice best practices could ensure that patient requests for physician-assisted death are voluntary, informed, and not motivated by uncontrolled pain or financial concerns.

PHYSICIAN PERSPECTIVES

Anthony Back

Professor of Medicine

University of Washington

Anthony Back told the workshop that from his perspective as a medical oncologist and palliative care physician, thinking about physician-assisted dying is no longer just for social pioneers. Back is a professor of medicine at the University of Washington and a co-director of the university’s Cambia Palliative Care Center of Excellence. Early on, Back said, he located an advocacy organization, End of Life Washington, that provides “end of life counseling to . . . qualified patients who desire a peaceful death,” among other services, including promoting the use of physician order for life-sustaining treatment forms.5 However, Back said, nowhere on that organization’s website does it recommend that patients find a palliative care doctor before pursuing physician-assisted death.

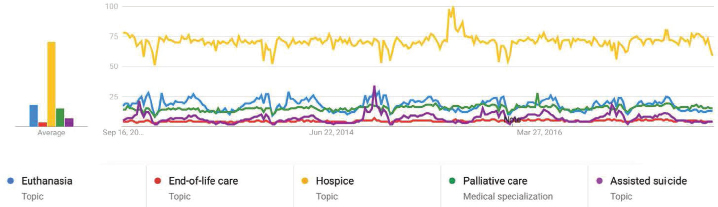

Back noted how Google searches of various words associated with end of life reveal some interesting patterns (see Figure 5-2). Searches on the word “hospice” far outnumber those on “euthanasia,” “end-of-life care,” “palliative care,” and “assisted suicide,” but those on “euthanasia” exceed those of “palliative care” and “end-of-life care.” Back concluded, “If you are an American looking at what happens in Google searches, you would conclude that a lot more people are searching for euthanasia than they are searching for palliative care.” A similar pattern is evident in worldwide searches, he added.

Back said he wonders if the public’s current confusion about the different options available for end-of-life care, as indicated by the Google search histories in Figure 5-2, represents an erosion of confidence in the medical care system or if there really is a new segment of the population that is willing to think about death in different ways. He said that colleagues of his at the University of Washington put an advance directive

___________________

5 For more information, see https://endoflifewa.org (accessed April 30, 2018).

SOURCES: Back presentation, February 12, 2018. Data from Back’s personal communication based on Google Trends analysis 2017.

for dementia on the Web and it was downloaded 43,000 times after it was mentioned in The New York Times (Gaster et al., 2017; Span, 2018).

Another aspect of physician-assisted death that Back said he considers to be important is the increasing number of patients he sees who want to access it because they want to have the option in the future, not because they have intolerable suffering in the present moment. Back said that he sees something of a “gift exchange” between patients who consider physician-assisted death and their loved ones—that is, the patient gives his or her loved ones a new perspective on approaching death, while receiving the gift of a “good” death in return. Back clarified that this concept of a “gift exchange” is complicated and not well described or understood and therefore an area for further research. As an example, he noted The New York Times story about John Shields, a social activist in British Columbia who used the new Canadian law and held his own Irish wake in the inpatient hospice ward where he was living a couple of days before he died (Porter, 2017). People showed up to this party who had not previously wanted to talk to him, and others used this occasion to make a final connection with him. This is not a new phenomenon, Back said, as there are records of the practice in ancient times, and goodbye parties became common in the time of HIV/AIDS (Mullan, 2000).

While the circumstances surrounding physician-assisted death are not quite analogous, Back said he thinks that there is something important about the idea of making arrangements so that the individual has the opportunity to better control various factors around their own death. He also sees this as a way for loved ones to say goodbye and perhaps make the grieving process easier for them.

Back also said that physicians and the public are experiencing a learning curve with the practice of physician-assisted death. In the first 6

months that California’s law was in effect, physicians who chose to prescribe lethal medications overwhelmingly did so for just one requesting patient. The first year that Oregon’s law went into effect told a similar story, with 14 physicians writing prescriptions for 15 patients (Chin et al., 1999). In the initial period after assisted-death legislation is passed, physicians individually have experience with a small number of cases. With physicians experiencing and responding to such a high-stakes procedure, it raises concerns about quality if a physician has no experience helping patients through the process. Back also mentioned the importance of physicians getting the appropriate support and training to have the sometimes subtle conversations about end of life. He said that End of Life Washington has a group of counselors, psychologists, and physicians who have been working together for 20 years doing this kind of counseling. This is a very intensive system, he said, and he wondered how to scale that type of program in California, which is 10 times the population of Washington. Back said that while physicians may be willing to participate, they will still need to have some training, both for their benefit and the benefit of patients.

To help patients navigate through the decision-making and documentation process, Back and colleagues at his institution have developed a death-with-dignity program (Loggers et al., 2013) based on a similar program implemented at Oregon Health & Science University. He has also worked with a large health system in California to teach its physicians that physician-assisted death is not about the law, but rather about the patient’s goals for end-of-life care. This health care organization, he said, has built a system of peer mentoring to support physicians. The effect of participating in an assisted death must be evaluated for clinicians just as it is for others who are part of the process, Back said, as he has observed a small number of negative psychological outcomes for clinicians who participate in assisted deaths. In closing, Back said that physician-assisted death is no longer an anomaly, and it is changing the experience of dying for everybody—not just the people who decide to use it.

Peter Reagan

Retired Family Physician, Oregon

Peter Reagan is a retired family physician who practiced for more than 30 years in Portland, Oregon. In March 1998, under Oregon’s new medical aid-in-dying law, he wrote the first legal prescription in the United States for a lethal medication. Over the next 13 years, he wrote some 25 prescriptions, of which 15 were used for a planned death. Reagan said he was present for three of these deaths, including the first. After he retired

from medical practice, for a few years he advised doctors in Oregon on the use of the law.

Reagan said that as he sees it, Oregon’s experience of the past 20 years has allowed the debate to move from whether aid-in-dying should be legal to how to best address the desire for it. He said he supports Oregon’s law, particularly because of the enhanced potential for communication it creates with patients and families. He noted that after 20 years and some 1,500 cases of aid-in-dying in Oregon, there has not been a single complaint of misuse filed with the Oregon medical board and almost no unexpected complications (Oregon Health Authority, 2018).

Reagan said that while there has been a fair amount written about a number of issues surrounding aid-in-dying, there has been little discussion in the literature about the communication that takes place among patients, family members, friends, caregivers, hospice workers, and other physicians when a request for aid-in-dying is made. Reagan stressed that physicians should look for consistency of requests for aid-in-dying from patients over time. Reflecting on the psychological and emotional burden for physicians, Reagan said that the more time a physician spends with the patient and his or her trusted circle of family and friends, the more comfortable the physicians can feel with an eventual decision to assist in a patient’s death.

Reagan recalled how before writing his first prescription, he spoke at length with the patient, each of her two adult children, both of her previous physicians who had been unwilling to consider prescribing, two hospice nurses, the hospice social worker, and the consulting physician as well as making a visit to the patient’s home to discuss the matter in a family setting. Talking to the patient’s usual physician, even if that physician will not provide the prescription, can provide valuable perspective on whether the patient would qualify under the law. He stressed the importance of avoiding prescribing the lethal medication if there is any real disagreement about whether the patient qualifies. Reagan also expressed his belief that the primary value of Oregon’s law is the high level of open communication it creates and requires among physicians, patients, and families. He said that communication is the essence of why an aided death feels so unlike death by suicide.

For patients who are not qualified under the law, Reagan said he favors alternatives such as palliative sedation or voluntarily stopping eating and drinking (VSED), as opposed to any illegal or clandestine approach, as these alternatives allow for a better resolution of unfinished business with loved ones.

Reagan said that there are specific illness-related issues that can affect how well a patient can self-administer and ingest life-ending medication. Patients with ALS, for example, can be mentally competent and yet have a

great deal of difficulty self-administering oral medications. Some patients have complied with the self-administration requirement by finding or inventing a way to initiate the flow of medication into a feeding tube. A difficult situation, Reagan said, is with people who have a poorly functioning digestive system, particularly when there is frequent vomiting, as these individuals are unable to absorb oral drugs and therefore cannot use the law. Another sad circumstance, he said, involves progressive dementing illness in which the patient loses decisional capability long before he or she is terminally ill. No state’s laws address this situation, leaving voluntarily stopping eating and drinking as the only legal choice for hastening death in this setting in the United States.

After ingestion of a lethal medication, unconsciousness occurs usually within minutes, and death results within an hour. However, a prolonged dying process is more common than many believe, Reagan said. Early data collected in Oregon suggested that about 15 percent of patients were still alive after 8 hours, and 1 to 2 percent lived more than 24 hours. An even smaller number, perhaps 1 in 200, might reawaken (Oregon Health Authority, 2018). This type of outcome is more common in patients with gastrointestinal cancer, when unusual prescriptions are used, when there is vomiting, or when a patient eats a large meal before ingesting the medication, he said.

According to Reagan, about 20 percent of oral aid-in-dying patients in the Netherlands received some form of intravenous euthanasia 2 or so hours after ingestion.6 In Oregon, when a dying process goes on for more than 8 to 12 hours, or when vital signs appear to be strengthening, buccal morphine or topical fentanyl patches are sometimes used. Reagan spoke of the value of discussing a prolonged dying process with the patient and family in advance, and he questioned whether legally, intentionally, and publicly ingesting a lethal prescription constitutes a form of consent for palliative sedation if that lethal medication fails to work as intended.

Perhaps the most frustrating aspect of aid-in-dying for patients and families is the lack of care continuity that results when the patient’s usual physician or health care system opts out of the program, Reagan said. In his opinion, he said, the current legal process is not too onerous when the usual primary care physician and relevant specialists are supportive. Under these circumstances, he said, the time from first request to prescription can easily be close to 3 weeks. However, it can take closer to 2 months when the first request requires finding a new doctor.

Reagan identified two modifications to current laws that could improve access without compromising safeguards. One such modification

___________________

6 Calculated from the Netherlands Regional Euthanasia Review Committee’s Annual Reports, 2002–2016.

would be to shorten the waiting period between requests. Instead of 15 days, 7 days should be possible, given research showing that even 3 days of attitudinal consistency correlates with long-term reliability (Chambaere et al., 2015; Lewis and Black, 2012; Oliver, 2016; Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al., 2010). It would be appropriate, he added, for a provider to require a longer waiting period in any circumstance where the decision appears to be unclear. Another issue is interstate reciprocity. It can be common for a patient to live in Washington State but work and get medical care in Portland, Oregon. Currently, a patient requesting assisted death would need to have all of the medical records based on his or her state of residence in order to access the law.

Erik Fromme

Director, Serious Illness Care Program, Ariadne Labs

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Erik Fromme, the director of the Serious Illness Care Program at Ariadne Labs, recently left a position as the director of palliative care at Oregon Health & Science University, where for 15 years he chose not to prescribe lethal medications for patients requesting physician-assisted death. As a non-prescriber, he had experience working with both patients who were interested in physician aid-in-dying and those who were uninterested in the option. Fromme’s goal was to maintain his ability to care for patients whether they were for or against physician aid-in-dying. In his opinion, physicians should never be in the position of suggesting aid-in-dying as an alternative for a patient. Fromme acknowledged that the necessity of respecting individual health professionals’ rights to not be involved in physician-assisted death means that accessibility becomes highly dependent on a health professional’s personal stance—in terms of individual providers as well as the entire health care systems. He explained that he maintained a bright line between palliative care and physician aid-in-dying during his time in Oregon, but he said that today he is unsure how important it is for the concepts of palliative care and physician aid-in-dying to be separate in the minds of clinicians, patients, and families. After all, palliative care physicians have the most experience caring for terminally ill patients. Is it reasonable for them to refuse to be involved in or serve as a resource for patients considering aid-in-dying?

Fromme said that there is a tension between non-encouragement and non-abandonment. For a physician who does not want to participate in aid-in-dying, doing nothing could feel like patient abandonment, whereas facilitating a request for aid-in-dying could feel like encouragement. He also said that a physician should take a different approach to handling patients who just want a prescription versus patients who think they

might need a prescription because they are worried about things getting out of control at the end. “Those may sound overlapping, but, in my experience, they are two very distinct groups of people,” he explained. He also noted that prognostic uncertainty puts clinicians in a vulnerable position because it is impossible to be entirely certain about when a patient will die, while an event of this magnitude demands a high level of certainty.

In his 15 years in Oregon, Fromme said, he never had a frivolous request for aid-in-dying. He added that he found that patients uniformly respected a clinician’s personal moral boundaries about participation and stressed that physicians should be upfront with patients early on if they are opposed so that the patient’s time is not wasted. He added that the patients he saw who were not terminally ill were anxious but generally willing to wait and see before considering aid-in-dying. However, patients who did not qualify for aid-in-dying because they did not or would not have decision-making capacity were often angry.

Reflecting on the rarity of psychiatric refusals, Fromme suggested that it is not that oncologists are determining that patients do not have decision-making capacity and thus do not bother referring them to mental health professionals. Rather, Fromme said that in his experience, any physician who is contemplating refusing a request based on a psychiatric diagnosis is going to make sure that a mental health professional makes the determination. He also said that the low rate of psychiatric referrals is in part a reflection of the fact that patients are making serious, as opposed to frivolous, requests. However, he said, in his experience it was apparent to him that some patients were coached on the right things to say and to not talk about symptoms of depression or anxiety.

Fromme commented that access to physician aid-in-dying has been limited in the urban area of Portland, Oregon. Three faith-based health systems and the Veterans Affairs medical center, which together account for the majority of health care services in the city, along with many smaller physician groups adopted policies that forbade their physicians to prescribe lethal medications or to discuss physician-assisted death with patients. This forced patients to either abandon their request or to seek care from one of two health systems that had not forbidden physicians to prescribe. One health system, however, changed its approach over time, he said. In 1997, that institution’s policy was to neither encourage nor discourage patients, and it prohibited its physicians from prescribing, serving as consultants, or referring patients anywhere else. In 2004 it updated its policy to allow its physicians to act as consultants and to refer patients to other resources, and in 2018 it decided to allow its physicians to prescribe end-of-life medications. This change in policy, Fromme said, was driven by the institution’s ethics committee, which justified the

change based on feedback from physicians who reported that they were being forced to abandon their patients at their greatest time of need.

In rural areas of Oregon, Fromme said, access to physician aid-in-dying is less clear, but the rates of request are low. Access to specialty palliative care is limited or non-existent in rural areas. He reported that many hospice organizations decided not to participate in physician aid-in-dying requests and that many rural physicians said they did not want to become involved in assisted deaths for fear it would alienate some in their communities.

REFLECTIONS ON PREPARING FOR AND RESPONDING TO LEGALIZATION IN CALIFORNIA

Barbara Koenig

Professor

University of California, San Francisco

On June 9, 2016, California’s End of Life Option Act (EOLOA) went into effect, something that was relatively unexpected for anyone who had not been involved in getting the legislation passed, said Barbara Koenig, a professor of bioethics and medical anthropology at the University of California, San Francisco’s (UCSF’s) Program in Bioethics. From her position as the director of bioethics at UCSF, she experienced the law’s passing as a “bioethics emergency” because suddenly institutions across California were challenged with the development of practices and procedures related to physician aid-in-dying. Koenig reported that while it may seem fairly straightforward to implement a relatively simple law, that was not the case.

Koenig’s first step was to approach several foundations, and together they convened key stakeholders around California for two meetings. The first, held in December 2015, brought together ethics committees, palliative care programs, and others to talk about the kinds of internal processes they would use as they set up their own policies that would go into effect in the next year. The second meeting, in September 2017, characterized California’s response 1 year after the law had been in effect.

This project has produced shared resources, Koenig said, including a project website with videos of the key plenary sessions at the two meetings7 and a paper summarizing the first meeting (Petrillo et al., 2017). Other members of the EOLOA Task Force are now conducting a survey of California’s health care systems’ progress in developing and implementing policies concerning physician aid-in-dying. This survey is ongoing,

___________________

7 See http://www.eoloptionacttaskforce.org (accessed March 22, 2018).

and many health systems have not yet developed policies, Koenig said, particularly those in rural areas. Another task force project is currently collecting in-depth patient, family, and provider narratives.

For Koenig and many of her colleagues, there is a sense of moral ambiguity associated with the topic of physician-assisted death. She argued that these moral concerns will not disappear and that if they did, that would be a reason for concern. While she is not opposed to physician aid-in-dying, she said, she has concerns about the practice becoming routine. Similarly, Koenig said, there has been notable ambivalence on the part of many institutions in California, even among those offering the option of an assisted death. There is also the concern, particularly among palliative care providers, about becoming the “go-to” physician or institution for patients requesting assisted death. To gain acceptance as a specialty, palliative care practitioners have had to overcome the idea that only the “dying” can benefit from such care.

Koenig said that an institution must consider a number of issues when determining how to respond to a law such as EOLOA. These consideration include

- Whether to allow the practice on the premises

- Who will participate

- How to honor the conscientious objections by providers while respecting patient choice

- What will be the role of palliative care

- How often will mental health evaluations be conducted

- How to determine if a patient should be referred for an ethics consultations

For example, while most hospitals do not allow the lethal medications to be ingested onsite, patients at a large long-term care institution often have nowhere else to go because the institution is their home. UCSF requires everyone to have a mental health evaluation, but that has created concern among some individuals, Koenig said, particularly those who have advocated for legal change. The issue of who on staff will participate also turned out to be more complicated than a simple yes or no, Koenig said. It often depends on context, including which patient is requesting physician-assisted death, and on other concerns, she said.

In general, she said, implementation has been difficult and uneven, and it requires significant resources, including clearly identified patient navigators. It is also clear that implementation is most practicable when a good hospice and palliative care program exists on which to build. In that regard, Koenig noted one conclusion that came out of her and Neil

Wenger’s shared work: physician-assisted death is difficult in places that lack quality hospice and palliative care programs.

One unique provision of the California law is that it has a sunset clause, meaning that it will end on January 1, 2026. As a result, Koenig and the other task force members feel some urgency in thinking about what would help the state decide whether the program should be continued after that time. Another feature of the law is that it requires a “final attestation.” As Koenig explained, patients are being asked to sign a document to indicate they are taking the drug before they actually take it, as opposed to when they get the prescription. The data collection efforts surrounding “final attestation” forms are not yet adequate, and therefore it is unknown whether the concept of documenting final ingestion of the lethal medication serves the purpose for which it was intended.

One unique issue that arose at the second stakeholder engagement meeting was that interpreters were being asked to sign documentation attesting to the voluntariness of the patient taking the lethal medication, which many interpreters believe is far out of their scope of practice. Koenig said that the state interpreter association is working on this issue.

The California Department of Health collects the data on the EOLOA, but it is not releasing the data to researchers. Another problem, Koenig said, is that it is hard to capture information about how end-of-life practices are serving or not serving patients from diverse backgrounds. Currently, information about race and ethnicity is captured from death certificates, which Koenig said she has learned from colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is a suboptimal way to capture that information.

Given these difficulties, Koenig said it will be important to develop best practices for collecting data, which will allow her and other researchers to more effectively study the impact of the law on the state’s diverse population. Koenig listed several questions that offer opportunities for additional research:

- How are patients with limited social and cultural capital able to navigate the system for requesting physician aid-in-dying?

- What is the effect of the waiting period, and what constitutes an official request? In California, Koenig’s team has seen instances where patients think they have made a request—because of conversations with clinicians—but it is not captured in a particular health care system.

- What has been the symbolic impact of EOLOA, and how has passage of the law affected end-of-life care and palliative care for people who are not going to take advantage of physician aid-in-dying?

- Is the desire for physician aid-in-dying part of a broader set of issues concerning the lack of trust people feel in the health care system?

- How can genuine, democratic public engagement around physician aid-in-dying be implemented?

DATA COLLECTION AND PUBLIC REPORTING

Matthew Wynia said that he became interested in data collection when he and two colleagues noticed that the Colorado physician-assisted death statute had “very thin” data reporting requirements. “We started to wonder why, and then we started looking across the country at other data reporting requirements,” he explained. The three of them, he said, realized that there are important ethical, policy, and research questions concerning physician-assisted death—and particularly concerning slippery slopes, the erosion of social and medical norms, barriers to and disparities in access, the frequency of complications arising during the procedure, and the safe disposal of unused drugs—that could only be addressed with good data.

Before he spoke about data sources across the country, Wynia offered his opinion on the matter of physician-assisted death. “Assisted dying is a low-frequency, high-risk medical procedure,” he said. “And we should start treating it like that within the medical profession and stop waiting for government and the state to tell us how to manage this.” With that on the table, he said that there are three main sources of data on physician-assisted death: physicians (see Table 5-1), patients (see Table 5-2), and pharmacists (see Table 5-3). Some states do better than others when it comes to data collection, with no data collection at all in Montana and the state legislature there having rejected a bill that would have initiated some data collection.

When looking at the data that states collect, there are some obvious gaps, Wynia said. For example, there is no state-collected information on how many patients had to change doctors to access this service. While death certificate data do exist, they are not collected specifically for the purpose of understanding physician-assisted death and do not record when death has occurred following the ingestion of aid-in-dying medications. Data from pharmacists are thin, and data from patients are even more so. Every state except Montana requires that patients fill out a request form and some kind of written attestation from a witness.

No state collects information from patients on their end-of-life concerns and motivations, though California, Oregon, and Washington ask physicians to report patient end-of-life concerns. In fact, published studies that address patient motivations typically get that information from

TABLE 5-1 Physician-Sourced Data in the Six Jurisdictions Where Physician-Assisted Death Is Legal

| CO | OR | WA | CA | VT | DC | MT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Patient’s end-of-life concerns (per MD) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Enrollment in hospice | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Enrollment in hospice at time of death | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Health status (ECOG) | ✓ | ||||||

| Patient ethnicity/race/education/insurance | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Which medication is dispensed | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Psychological written report/attestation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Interpreter used/attestation | ✓ | ||||||

| Physician specialty | ✓ | ||||||

| Duration of physician–patient relationship | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Hospital/health system of physician | |||||||

| Physician/other professional present at ingestion | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Time between ingestion, unconsciousness, and death | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Complications (regurgitation, regained consciousness, EMS activated) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Cause of death (ingestion, illness, other) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

NOTES: EMS = emergency medical services; MD = medical doctor. ECOG is a measurement scale used by physicians to assess how illness or poor health impacts a patient’s daily living abilities. For more information, see http://ecog-acrin.org/resources/ecog-performance-status (accessed June 21, 2018).

SOURCES: Wynia presentation, February 13, 2018. Data from Abbott et al., 2017.

TABLE 5-2 Patient-Sourced Data in the Six Jurisdictions Where Physician-Assisted Death Is Legal

| CO | OR | WA | CA | VT | DC | MT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Witness attestation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Document if family informed | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Needed to change physician to access AID | |||||||

| End-of-life concerns/motivation for AID | |||||||

| Final personal attestation of capacity | ✓ |

NOTE: AID = aid-in-dying.

SOURCES: Wynia presentation, February 13, 2018. Data from Abbott et al., 2017.

TABLE 5-3 Pharmacist-Sourced Data in the Six Jurisdictions Where Physician-Assisted Death Is Legal

| CO | OR | WA | CA | VT | DC | MT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Which medication(s) prescribed | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| To whom medication is dispensed | |||||||

| Medication follow-up mechanism | ✓ | ||||||

| Pharmacist attestation form | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

SOURCES: Wynia presentation, February 13, 2018. Data from Abbott et al., 2017.

doctors, not from the patients themselves, Wynia said. “I will leave it to you to guess how accurate doctors are at assessing their patient’s motivations,” he said, “but if you look at other domains of medical care, you have reason to believe that doctors are not perfectly accurate in understanding why patients are making the decisions that they are making.” He pointed out that 56 percent of the prescriptions written in Colorado are for a newer medication protocol that costs about $500, compared to approximately $4,000 for secobarbital (Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, 2018). However, the paucity of data means that little is known about complications and how this not-so-simple regimen is being used.

In Colorado, the light collection burden was a result, in part, of the fiscal note attached to the ballot initiative put before the state’s voters. The fiscal note on this ballot measure was $45,000, which is all that the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment is allocated for data collection, analysis, and reporting. This is just enough money to collect data mandated by the law and nothing else, Wynia said. A second reason for the light data collection burden was that it was seen as being helpful in getting physicians to participate, though Wynia said that he has not heard of physicians complaining about the forms they have to fill out for this procedure. He added that he and his colleagues have been trying to improve data collection in the state, but advocates who supported the law are pushing back against collecting more data. He said he finds that ironic, given that these advocates used data from Oregon to bolster their arguments in favor of the law in Colorado, and better data collection could be used to address issues of unequal access and other concerns of these advocates.

As a final comment, Wynia reiterated his earlier statement that assisted dying is a low-frequency, high-risk procedure, and that health professions should start treating it as such. “It is our responsibility and not the responsibility of the government, and not the responsibility of activists, to establish a national registry and to have standard data reporting elements and reporting requirements,” he said. “This is something that our professional associations should be doing.”

Katrina Hedberg said that there is a need for data not just on physician-assisted death but on all aspects of end-of-life care. Hedberg indicated support for generating more knowledge about options and decision making at the end of life, although the state government is not necessarily in the best position to collect this information. Research on end-of-life options and decisions might be better collected by those directly caring for these patients, such as hospice organizations or academic health settings, such as those with cancer centers or neurological clinics treating patients with ALS. While she is supportive of this research,

Hedberg said that she and her colleagues at the Oregon Health Authority have made it a policy not to collaborate with outside researchers because of the confidentiality issues they face in dealing with the data reported to the state. Reflecting on how to improve data collection, Hedberg said it will be important to clarify the role of government and academia as Oregon does not provide funding for data collection beyond that required for monitoring and reporting.

In the Netherlands, Bregje Onwuteaka-Philipsen said, the government collects data every 5 years by taking a stratified sample of approximately 6,000 deaths and sending each attending physician a questionnaire with guaranteed anonymity. From a sample of those physicians, the government also conducts follow-up interviews to get more insights, experiences, and opinions from physicians.

Canada’s legislation required that the federal minister of health work with the provinces and territories to develop a regulatory framework that focuses on compliance for transparency and public trust, Jennifer Gibson said. So far, she said, the federal government and Health Canada have issued guidelines on death certificates in order to ensure some consistency across the country on how medically assisted deaths are reported. The federal government and Health Canada are also working with the provinces and territories to develop regulations regarding monitoring compliance with federal, provincial, and territorial regulations.

Gibson said that the provinces and territories themselves have been actively involved in developing measures to monitor compliance in their own settings. In fact, she said, some provinces and territories are able to track indicators on access, on the numbers of requests and types of requests, and on reasons for why requests are not granted. The success at gathering this information varies at the local and institutional level, and the data collections systems are not well integrated at this point, but there are conversations and efforts aimed at creating a seamless national data collection system, Gibson said.

The Canadian government’s consultations with a wide range of stakeholders has revealed some pragmatic concerns about data collection, she said. The potential burden on practitioners has been raised as a concern, as have concerns about ensuring privacy protection for patients, practitioners, and the pharmacists who dispense the lethal medications. Gibson said that physicians and nurse practitioners have expressed concerns about the clarity of the reporting requirements. She said that these health care professionals want to understand the reporting requirements and how best to meet them.

In Canada, Gibson said, there is an interest in identifying a set of minimum indicators that could be used for the purposes of comparison, sharing lessons, and aligning times for reporting in the context of the

realities of clinical practice. Initially, reports were expected within 10 days, she said, but based on feedback from practitioners, there is a proposal to extend the reporting time to 30 days. Gibson added that there is also interest in using data not only for monitoring compliance but also to better understand which data matter with regard to equity, quality, and the broader social impact of medical aid-in-dying as well as to learn how to gain more insights into patient and public perspectives. In closing, Gibson said she wanted to add her voice to those of the other speakers to say that the research community—not just the government—needs to be involved in data collection. In addition, she said, funders need to support data collection efforts to ensure that any research agenda will be to serve the public interest and to leverage expertise to ensure that the continuum of end-of-life care, and not just medical assistance in dying, is done well.

REFERENCES

Abbott, J. T., J. J. Glover, and M. K. Wynia. 2017. Accepting professional accountability: A call for uniform national data collection on medical aid-in-dying. Health Affairs Blog: End of Life & Serious Illness. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20171109.33370/full/https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20171109.33370/full (accessed May 24, 2018).

Boring, N. 2014. Belgium: Removal of age restriction for euthanasia. Global Legal Monitor, March 11.

California Department of Public Health. 2017. California End of Life Option Act 2016 data report.https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CHSI/Pages/End-of-Life-Option-Act-.aspx (accessed May 24, 2018).

Chambaere, K., R. Vander Stichele, F. Mortier, J. Cohen, and L. Deliens. 2015. Recent trends in euthanasia and other end-of-life practices in Belgium. New England Journal of Medicine 372(12):1179–1181.

Chin, A. E., K. Hedberg, G. K. Higginson, and D. W. Fleming. 1999. Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act: The first year’s experience. Portland: Oregon Health Division.

Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. 2018. Colorado End-of-Life Options Act, year one: 2017 data summary. Denver, CO: Department of Public Health and Environment Center for Health and Environmental Data.

Death with Dignity National Center. n.d. Frequently asked questions about death with dignity. https://www.deathwithdignity.org/faqs (accessed April 27, 2018).

Gaster, B., E. B. Larson, and J. R. Curtis. 2017. Advance directives for dementia: Meeting a unique challenge. JAMA 318(22):2175–2176.

Gerein, K. 2017. Young patients, their parents now asking for medical aid in dying: Pediatricians’ group. The Edmonton Journal, October 25.

Hedberg, K., and C. New. 2017. Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act: 20 years of experience to inform the debate. Annals of Internal Medicine 167(8):579–583.

Lewis, P., and I. Black. 2012. The effectiveness of legal safeguards in jurisdictions that allow assisted dying. London, UK: King’s College London Dickinson Poon School of Law.

Loggers, E. T., H. Starks, M. Shannon-Dudley, A. L. Back, F. R. Appelbaum, and F. M. Stewart. 2013. Implementing a death with dignity program at a comprehensive cancer center. New England Journal of Medicine 368(15):1417–1424.

Mullan, F. 2000. Angels in America. The New York Times, August 13.

Oliver, P. 2016. “Another week? Another week! I can’t take another week”: Addressing barriers to effective access to legal assisted dying through legislative, regulatory and other means. Thesis submitted to the University of Aukland. https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/29864 (accessed May 24, 2018).

Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D., M. L. Rurup, H. R. Pasman, and A. van der Heide. 2010. The last phase of life: Who requests and who receives euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide? Medical Care 48(7):596–603.

Oregon Health Authority. 2018. Oregon Death with Dignity Act: 2017 data summary.http://www.oregon.gov/oha/ph/providerpartnerresources/evaluationresearch/deathwithdignityact/pages/ar-index.aspx (accessed May 7, 2018).

Ouellette, A. 2017. Barriers to physician aid in dying for people with disabilities. Laws 6(4):23. doi: 10.3390/laws6040023.

Petrillo, L. A., E. Dzeng, K. L. Harrison, L. Forbes, B. Scribner, and B. A. Koenig. 2017. How California prepared for implementation of physician-assisted death: A primer. American Journal of Public Health 107(6):883–888.

Porter, C. 2017. At his own wake, celebrating life and the gift of death. The New York Times, May 25.

Scottish Parliament. 2010. End of life assistance (Scotland) bill. http://www.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/Bills/21272.aspx (accessed April 27, 2018).

Snyder Sulmasy, L., and P. S. Mueller, for the Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee of the American College of Physicians. 2017. Ethics and the legalization of physician-assisted suicide: An American College of Physicians position paper. Annals of Internal Medicine 167(8):576–578.

Span, P. 2018. One day your mind may fade. At least you’ll have a plan. The New York Times, January 19.

Stokes, F. 2017. The emerging role of nurse practitioners in physician-assisted death. Journal for Nurse Practitioners 13(2):150–155.

Washington State Department of Health. 2017. Washington State 2016 Death with Dignity Act report.https://www.doh.wa.gov/YouandYourFamily/IllnessandDisease/DeathwithDignityAct/DeathwithDignityData (accessed May 24, 2018).