1

Introduction

On December 5, 2017, the Food Forum of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine hosted a public workshop titled Nutrigenomics and the Future of Nutrition in Washington, DC, to review current knowledge in the field of nutrigenomics as it relates to nutrition. Workshop participants explored the influence of genetic and epigenetic expression on nutritional status and the potential impact of personalized nutrition on health maintenance and chronic disease prevention (see Box 1-1 for the workshop’s complete Statement of Task).1

In her welcoming remarks, Food Forum chair Sylvia Rowe, SR Strategy, LLC, described how the Food Forum, through public workshops such as this, convenes scientists, administrators, and policy makers from academia, government, industry, and the public sector to discuss problems and issues related to food, food safety, and regulation and to identify possible approaches for addressing these problems and issues. She emphasized that while the forum compiles information, develops options, brings interested parties together, and provides a rapid way to identify areas of concordance among workshop participants, it does not make recommendations, nor does it offer specific advice. She noted that, in addition to diverse and ex-

___________________

1 The role of the workshop planning committee was limited to planning the workshop, and this Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the rapporteur as a factual account of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

pert presentations, the agenda for the workshop included built-in time for discussion.

This Proceedings of a Workshop is a factual summary of the presentations and discussions that took place during the workshop. It is not intended to serve as a comprehensive overview of the subject, nor are the citations herein intended to serve as a comprehensive set of references for any topic. Additionally and importantly, the information presented here reflects the knowledge and opinions of individual workshop participants and should not be construed as reflecting consensus on the part of the workshop planning committee; the Food Forum; or the National Academies.

SETTING THE STAGE: INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

Following Rowe’s welcoming remarks, Patsy Brannon, Division of Nutritional Sciences, Cornell University, set the stage for the workshop by discussing the central role of a risk assessment framework in current, population-based dietary guidance and the challenges of transitioning to personalized nutrition guidance. Her presentation is summarized here, with highlights provided in Box 1-2.

An Overview of Population-Based Dietary Guidance: The Centrality of the Risk Assessment Framework

Brannon began by discussing the risk assessment framework, which she said underlies many, though not necessarily all, current population-based dietary guidance. She explained that the first step in risk assessment is to identify, based on a review and synthesis of evidence in the literature, what is known in the field of risk assessment as the “hazard identification,” which, in the context of nutrition, is a health outcome. The second step, she continued, is to characterize the dose-response relationship between the exposure, which in this case is a nutrient or diet, and the health outcome. “These two steps are central to why we use a population-based approach,” she said. She then discussed each step in detail.

Step 1: Synthesizing the Evidence

In addressing the process of synthesizing the evidence, Brannon cited two sources: (1) food-based dietary guidance from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and also, to some extent, from the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, particularly the Nutrition Evidence Library; and (2) nutrient requirements, including the dietary reference intakes (DRIs),

particularly the traditional DRI model (that is, before chronic disease endpoints were proposed).

EFSA’s population approach, as reflected in its Scientific Opinion on Establishing Food-Based Dietary Guidelines (EFSA, 2010), focused explicitly on dietary patterns, which Brannon noted is comparable to the focus of the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans (HHS/USDA, 2015), emphasizing “desirable food and nutrient intakes.” But, she added, EFSA’s focus also was on diet and disease relationships of relevance to a specific population. She explained that the EFSA (2010) panel used a stepwise approach in reviewing the evidence and identifying diet–health relationships, country-specific diet-related health problems (in contrast to the U.S. focus on nationwide health problems and their public health significance), nutrients of public health concern, foods relevant for food-based dietary guidelines, and food consumption patterns. She commented that, other than the focus on country-specific diet-related health problems, EFSA’s approach was comparable to that used to establish the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

Brannon then turned to the analytical frameworks used for the synthesis of evidence in establishing the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which, like the EFSA approach, reflected a population-based approach. She cited the example of the framework used to evaluate adherence to a dietary pattern in relation to outcomes for breast, colorectal, prostate, and lung cancers.

Step 2: Characterizing Dose-Response Relationships

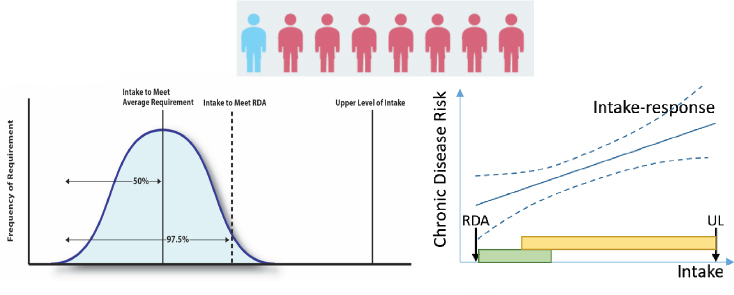

Brannon next considered how an understanding of the DRIs is helpful for understanding why the U.S. population-based approach is different from what is possible with nutrigenomics. The DRIs, she explained, are based on a distribution of intake requirements, so that it is impossible to ascertain where in the distribution a given individual falls (IOM, 2006).2

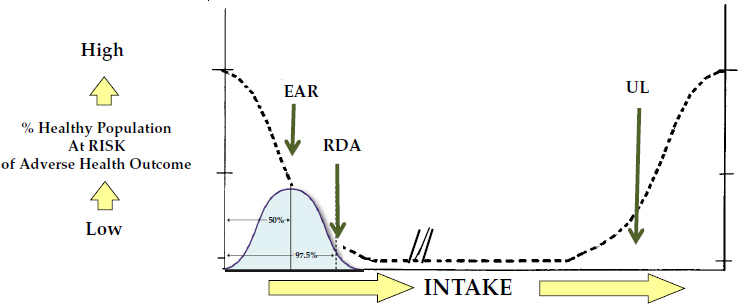

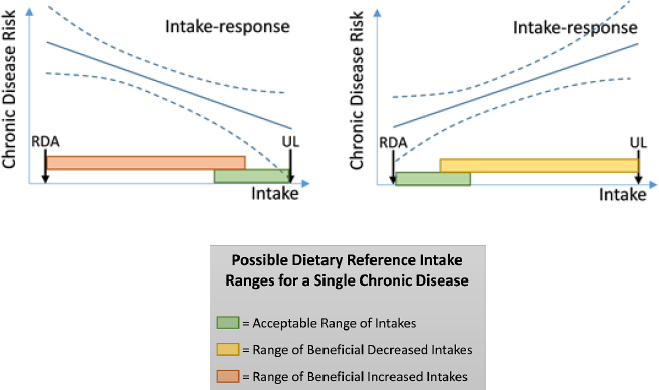

As shown in Figure 1-1, the DRI values include the estimated average requirement (EAR) for 50 percent of the population, a recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for 97.5 percent of the population, and an upper level (UL) at which adverse effects begin to be seen. The European approach, Brannon noted, uses comparable values. She added that the proposed chronic disease DRIs (NASEM, 2017a) are based on acceptable ranges of intakes instead of singular dietary reference values (see Figure 1-2).

Because of this distribution-based approach, Brannon observed, “we have been unable to give a specific recommendation for an individual, and that is at the heart of the change of what nutrigenomics opens up as a possibility.” This is true, she noted, for both the current model (left distribution in Figure 1-3) and the proposed expanded model with chronic

___________________

2 More about the DRIs can be found at www.nas.edu/dris (accessed April 23, 2018).

SOURCE: Presented by Patsy Brannon on December 5, 2017.

NOTE: RDA = recommended dietary allowance; UL = tolerable upper intake level.

SOURCES: Presented by Patsy Brannon on December 5, 2017, from NASEM, 2017a.

SOURCE: Presented by Patsy Brannon on December 5, 2017.

disease endpoints (right distribution in Figure 1-3). She suggested that this distribution of requirements raises the question of why there is variability in requirements for a nutrient or in the response to a nutrient or dietary component related to health promotion or disease prevention.

Nutritional Kinetics, Dynamics, and Requirements

Brannon chose to frame her consideration of the question of variability in terms of nutritional kinetics, dynamics, and requirements because she believes it is useful to step back and ask, Why do people actually vary? She explained that when people consume food, there are both kinetic and dynamic aspects to the nutrient concentration at the site of action.

Brannon listed several different processes related to kinetics: absorption (e.g., processes related to digestion and bioavailability); distribution throughout the tissues (e.g., processes related to the volume of circulating fluids, the volume of the compartments into which they are being distributed, and body composition); metabolism, including metabolic rates; and excretion, including rates of excretion.

Likewise, Brannon continued, there are several different processes involved in dynamics that affect the actions of a nutrient. Among these processes are dose-response at the site of action (including complexities related to the differential distribution of nutrients in different compartment pools and their differential effects), maximal efficacy, and the temporal response

as nutrients are consumed. Adverse or beneficial effects, Brannon observed, also depend on dose-response at the site of action and the target tissue, as well as on deficiency; toxicity; temporal response; and, for DRIs for chronic disease, the ranges of dose-response effects. Additionally, she noted, as more is learned about the inflammatory response, it is clear that the dynamics of nutrients, as well as some of their kinetics, can also be influenced by the inflammatory response.

Brannon then cited a number of factors that affect individual variation in nutritional kinetics and dynamics, including genetics, epigenetics, and nutrient–gene interactions. She explained that genetics encompasses both the mitochondrial genome and the nuclear genome, plus interactions between the two, as well as other factors including age, sex, and physiological state (e.g., growing, pregnancy, lactation, stress, disease). Also relevant are nutrient–diet interactions, nutrient–environment interactions, and drug–nutrient interactions. When one considers all of these processes and factors, Brannon observed, “it becomes quite clear why nutrigenomics can help us understand what an individual needs as opposed to an average for the population.”

Definitions of Nutrigenomics

Upon searching for definitions of nutrigenomics, Brannon found that what she thought nutrigenomics meant agreed largely with how it was defined, including by such authoritative sources as Nature and medical dictionaries. However, she noted, although all of the definitions included nutrients, their impact on health, and the interaction between nutrients and genetics, they varied in how they characterized those relationships. For example, some focused on nutrients affecting health, with the effect being mediated through genetics, whereas what she described as more reflective definitions pointed out, first, that nutrients and the genome interact with each other and are mutually influencing and, second, that nutrients and health influence each other.

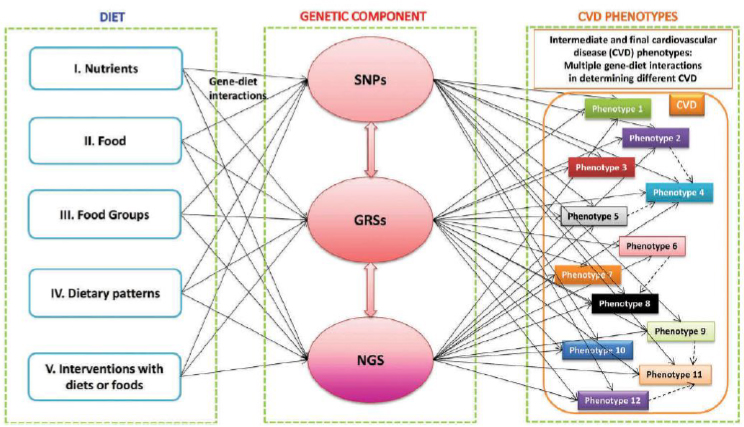

Additionally, Brannon found variability in whether a definition included nutrients, diet, foods, or food components. She sees this variability, coupled with the mutuality of nutrient–health and nutrient–genome relationships, as reflecting the complexities of nutrigenomics and their impact on how nutritional and dietary guidance would be provided to a specific individual. She pointed to Figure 1-4 as making these complexities readily evident, noting that the dietary and genetic interrelationships depicted in this figure are multiple and complex, affecting different phenotypes for, in this example, cardiovascular disease. She suggested that all of these complexities will need to be addressed as nutrigenomics begins to be applied to specific, personalized nutrition.

NOTE: GRS = genetic risk score; NGS = next-generation sequencing; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism.

SOURCES: Presented by Patsy Brannon on December 5, 2017, from Corella et al., 2017. Reprinted by permission from Taylor & Francis Group: Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics. D. Corella, O. Coltell, G. Mattingley, J. V. Sorli, and J. M. Ordovás. Utilizing nutritional genomics to tailor diets for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a guide for upcoming studies and implementations. 17(5):495–513, copyright (2017).

Consumer and Food Behavior

Adding to the complexity illustrated in Figure 1-4, Brannon continued, is the reality that consumer and food behavior is “very, very difficult to fully elucidate and understand.” She noted that each consumer is a complex psychological unit that informs both poor and good food behavior choices. She stressed that, based on the body of literature on consumers and food behavior, one issue that will need to be addressed is the reality that health is not the only driving force in food choices, and likely not even the major one. She acknowledged that, based on the theory of self-determination, health can be an important driving force in food choices, and it is known that as individuals’ health changes, their willingness to think about their health and the framing of their food choices can also change. However, she added, she knows many clinical dietitians who wish effecting change in

food choices were as simple as telling a patient, “You have this disease and you need to make this change in your diet.” “The reality is far different and more difficult to understand and influence,” she stated.

Rather than health, Brannon continued, taste is often the primary force behind food choices. Even when dining with fellow nutritionists, she may hear them say, almost with a guilty chuckle, such things as, “Well, I know I shouldn’t eat this, but I really like the way it tastes.” That is the reality of how people choose their foods, she asserted, and while nutrigenomics may change how people frame their choices and influence how they prioritize health, taste will remain an important factor.

Another issue Brannon believes will need to be addressed is that behavior change is neither easy nor fully understood. Nor are professionals necessarily as effective as they would like to be in facilitating behavior change in their clients and customers.

Finally, Brannon observed, individual consumers face a barrage of conflicting information about the risks of disease and diet and what to do about them both, and now they are faced with conflicting information about nutrigenomics as well. She stressed the importance of remembering that consumers want simplicity, clarity, and direction. In sum, she said, “As we move forward in nutrigenomics and the future of nutrition and diet advice, we are going to need to keep in mind what consumers are going to want.”

Integrating Population-Based and Personalized Dietary Guidance

Brannon next reflected on the many discussions related to nutrigenomics that pose guidance as either population-based or personalized for the individual, observing that the world is not that simple or clear cut. She argued that population-based and personalized dietary guidance will need to be integrated.

Brannon commented on the fact that 43 nutrients need to be supplied in the diet and that these nutrients exist in variable amounts in different foods. For example, she elaborated, the reason there is more protein in MyPlate than is actually required in the DRI is that some food groups rich in protein are rich in micronutrients, such as riboflavin, that are not abundant in the food supply. Thus, she explained, achieving a personalized dietary pattern meeting the needs for all of these nutrients would involve modeling a very complex set of multifactorial, interactive issues while also considering other bioactive food components. In sum, she said, much will have to be learned about nutrigenomics and its complexities before it can be applied as a sole approach.

Nutrigenomics and the Future of Nutrition: Complexities and Opportunities

In closing, Brannon presented an outline for the remainder of the workshop. Session 1 would focus on the interrelationships among diet, genomics, and health or disease prevention. Session 2 would focus on ways of applying nutrigenomics to diets tailored to individuals. Session 3 would turn to policy and ethical implications, with a close look at the nature and strength of the evidence—both what it needs to be and what it is—in terms of consumer perspective and behavior. Lastly, Session 4 would conclude with a panel discussion on the opportunities for nutrigenomics and the future of nutrition.

ORGANIZATION OF THIS PROCEEDINGS

The organization of this Proceedings of a Workshop parallels that of the workshop (see Appendix A for the workshop agenda). Chapter 2 summarizes the first portion of session 1 on Nutrigenomics and Chronic Disease Endpoints, which included two presentations. Chapter 3 summarizes the remainder of session 1 on Personalized Nutrition in the Real World. Chapter 4 turns to session 2 on Nutrigenomics Applications: Dietary Guidance and Food Product Development. Chapter 5 describes the presentations of session 3 on Nutrigenomics: Regulatory, Ethical, and Science Policy Considerations. Finally, Chapter 6 summarizes session 4, the panel discussion on Rethinking the Relationship Between Diet and Health: Can Nutrigenomics Help?