2

Gaps in the Global Medical Supply Chain

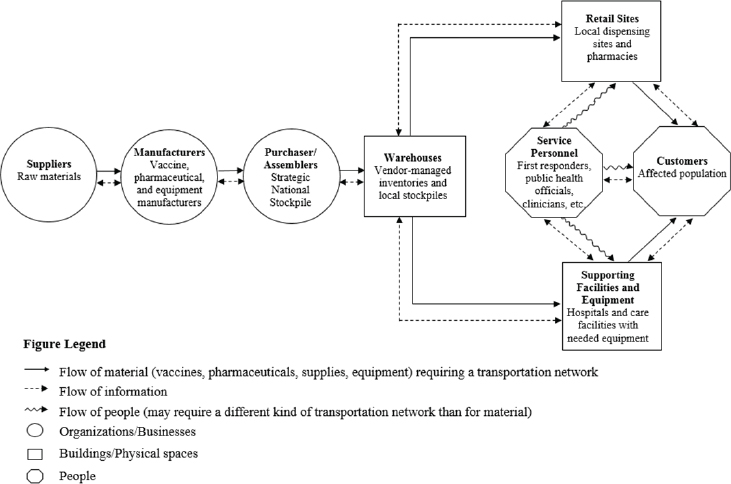

In her presentation at the Standing Committee’s first public workshop, Margaret Brandeau, Coleman F. Fung Professor of Engineering at Stanford University, defined the public health response supply chain necessary for the rapid procurement and distribution of medical and pharmaceutical supplies, trained personnel, and information in a public health emergency (NASEM, 2016). Her schematic of this chain, reproduced in Figure 2-1, emphasizes the flow of materials, information, and people through a system encompassing the global commercial medical supply chain that provides MCMs to the SNS, as well as the recipients of its assets: public health agencies and officials, health care providers, and patients.

To further explore gaps in the public health response supply chain discussed in response to Brandeau’s presentation and in subsequent meetings of the SNS Standing Committee, two workshop panels focused on the role of the SNS in both commercial and public components of the public health response chain. This chapter summarizes a discussion involving three experts representing different points along the commercial medical supply chain, guided by questions posed by Laura Runnels, consultant at LAR Consulting, LLC, followed by an open question-and-answer session. The next chapter summarizes a similar discussion focused on the ways in which SNS assets are requested, distributed, and delivered to patients during public health emergencies.

As he introduced the first panel, SNS Standing Committee member Larry Glasscock, senior vice president, Global Accounts, MNX Global Logistics, said that prior discussions of the global medical supply chain had raised his awareness of the pervasiveness of third-party foreign manu-

facturing of medical supplies, and also of the importance of the global marketplace for raw materials and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from which medical equipment and drugs are derived. “Most people don’t understand the amount of material that’s actually imported that goes into [medical] manufacturing,” he observed—and as a result, few recognize the significance of the relationship between the SNS and its private-sector partners, who are driven by economic incentives that may not align with SNS objectives. For example, MCM manufacturers may benefit from keeping inventories leaner than would be required to meet the SNS’s needs in the event of a disaster. “There’s a greater likelihood of shortages than most people realize,” he concluded.

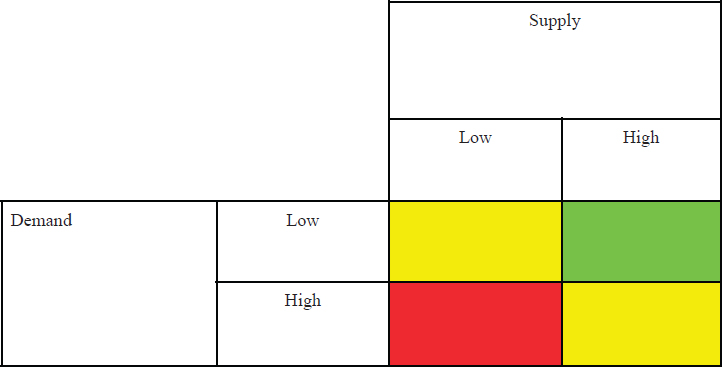

Shortages and other gaps in the global medical supply chain represent a mismatch of supply and demand (see Figure 2-2) when supply is low and/or demand is high for particular items, Runnels explained. An example might be when demand for particular medicines or devices is high or predicted to increase, as would occur during the early days of a disease outbreak or a natural disaster, or when an item’s production is reduced or projected to be inhibited by a disruption upstream in the supply chain, such as a raw material or API shortage.

SOURCE: Brandeau presentation, February 4, 2016.

NOTE: High supply/low demand (green box) is the most desirable scenario; low supply/high demand (red box) is the least desirable scenario.

SOURCE: Runnels presentation, August 28, 2017.

WEAK LINKS IN THE SUPPLY CHAIN

After introducing and locating themselves along the global medical supply chain, the three panelists discussed their experiences of gaps in the chain and the causes and effects of such gaps. Beginning upstream, panelist Brad Noé is global manager, Technical Resources, for manufacturer Becton, Dickinson and Company (BD), and in that capacity is responsible for domestic and global pandemic planning related to BD’s needle and syringe business. Panelist Allison Neale is director of public policy for Henry Schein, a global distributor of health care products and services to office-based physicians, dentists, and veterinarians, and the private-sector lead of the global Pandemic Supply Chain Network (PSCN). Representing the “last mile” of the private-sector medical supply chain, pharmacist Michele Davidson is senior manager for Pharmacy Technical Standards, Development and Policy, and Government Relations for the retail pharmacy chain Walgreens.

Day-to-Day Gaps: Raw Materials and Medicine Shortages

The panelists first described gaps in the supply chain that occur without the pressure of emergency events. Runnels asked the panelists to share their perspectives on where the supply chain is most fragile. Two primary

areas emerged in subsequent discussion: Interruptions in the supply of raw materials to manufacturers, and shortages of essential medications supplied to distributors and pharmacies.

Neale noted that many raw materials are imported from very limited geographic areas; for example, she said, 90 percent of the latex for sterile gloves is produced in Malaysia (MRB, 2016), and a significant portion of surgical hand instruments are manufactured in Pakistan. Local or national disruptions in raw material production or export from such key locations—resulting from any of the destabilizing factors known as the “four Ps”: powerful weather, pandemic, port closures, and political instability—would have serious repercussions worldwide, she observed.

Further down the chain, a trend toward consolidation among raw material suppliers over the past decade has increased risk for interruptions in the flow of raw materials to manufacturers such as BD, Noé reported. Recognizing this, BD is increasingly purchasing its raw materials from multiple sources when possible, and avoiding sources located in politically or otherwise unstable regions. He also noted the importance of international trade in products such as personal protective equipment (PPE), of which China provides a significant portion to the United States.

BD attempts to limit supply risks associated with marketplace contractions and consolidation by continually seeking new suppliers, according to Noé. This is a costly effort, consuming about half of the company’s budget for research and development, he reported; validating a new supplier, even when successful, can take 18 months.

Davidson noted that raw material shortages ripple downstream to retailers of common products such as blood pressure medicines. When that happens, she said, retail pharmacists must either offer patients alternative medications or ration the amount each patient receives when prescriptions are filled. Like BD, Walgreens attempts to reduce the risk of shortages by diversifying their manufacturing partners whenever possible. Insurance reimbursement sometimes limits Walgreens’s ability to substitute a branded medication for a generic in short supply, complicating efforts at addressing drug shortages. Davidson also reported that Walgreens’s pharmacists recently had compounded whooping cough medications to meet demand due to a local outbreak. “It is crazy what we have to do, but we get very creative when we have to,” she said.

Shortages of essential medications often create additional shortages in products used as stopgaps, Noé said. For example, due to a national back order on sodium bicarbonate, compounding pharmacies have been making and packaging it in 60 milliliter syringes—which are themselves now in short supply, in part due to high demand, and also due to an interruption in raw materials for syringe manufacture, he explained. Many other products are on back order because FDA barred several India-based sup-

pliers of API due to safety violations. Noé went on to explain that a large amount of manufactured sodium bicarbonate used in the United States has traditionally been imported from India, but safety concerns raised by U.S. regulators over the past 2 years has limited the amount of Indian-made sodium bicarbonate available on the American market. Hundreds of drugs are currently listed on websites that track medication shortages, Noé said, including FDA (FDA, 2018) and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP, 2018).

Supply Chain Structure and Surge

Pressure to reduce inventory costs has created inflexible conditions across the global medical supply chain. For manufacturers such as BD, this means maintaining lean inventories: a 15-day reserve of fast-moving products, and up to 60 days for slow-moving ones, Noé reported, while distributors hold 18- to 30-day supplies of these items. Margins are likely to get even thinner, and supply chains leaner, if distribution giants such as Amazon enter the health care arena, Glasscock observed.

Walgreens and other large pharmacy retail chains no longer warehouse medical products, Davidson stated. “It just doesn’t make sense to hold that material in a central warehouse for your company anymore,” she explained. Because Walgreens’s inventory depends completely on that of its distributor, AmerisourceBergen Corporation (ABC), any shortage experienced by ABC immediately affects Walgreens.

Some hospital chains have adopted similar “just-in-time” inventory practices, according to Noé, who reported that Kaiser Permanente plans to coordinate with their distributor to maintain 24-hour replenishment of inventory in 80 percent of their clinics and facilities by the end of 2018. “That’s amazing,” he remarked. “That also means there is no elasticity.”

As a result of this trend, the SNS has become not so much a stockpile as an inventory management strategy, observed Standing Committee member Sheldon Jacobson, Founder Professor in Computer Science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Such a strategy must incorporate knowledge of—and anticipate weaknesses in—individual MCM supply chains as they exist under both steady-state and surge conditions, he said.

Jacobson noted that during public health crises, supply chains for certain items undergo a critical shift in response to sudden high demand. “When you go from steady state to surge there’s something called a phase transition,” he explained. “It can be absorbed as we move through a threat, and then at some point it flips [back to steady state].” Planning for phase transitions includes strengthening links in the supply chain to accommodate temporary increases in demand for specific items, he concluded.

However, as several workshop participants noted, predicting surge

demand is difficult and may depend on multiple factors. For example, Noé pointed out, “phantom demand” arises when facilities or distributors, predicting an impending shortage, order more of a pharmaceutical or medical item than they may actually need, then cancel orders as soon as demand is met. During the 2009 H1N1 influenza outbreak, when vaccine delivered overnight to facilities arrived days in advance of syringes, bandages, and other non-perishable items needed to conduct immunizations, double and triple orders of the “slow” items were commonplace, he recalled. For BD, the resulting overbuying of syringes produced “demand curves that were out of sight,” followed by a drop in orders, as facilities gradually used up their excessive syringe inventories. On the other hand, he noted, in some situations, demand for specific items can drop off mid-crisis when facilities discover alternatives to high-demand supplies (e.g., different sizes of syringes). “That’s where you start to see . . . inconsistency within the supply chain, [and] you’re trying to guess what you can do best to be able to provide product to people, and you try and limit access to certain things,” he said.

Lead times for raw materials not only constrain manufacturers during surges, but also add to the cost of response, Noé added. In some cases, surge orders of raw materials—in quantities that in some cases drastically deplete their markets—reach manufacturers just as demand for their product falls off, he reported. The consequences of inelasticity, which underlies everyday drug shortages and volatility across the global medical supply chain, can only worsen under surge conditions, he concluded.

Effects of Emergencies on the Medical Supply Chain

Runnels asked each panelist to describe how, from their various perspectives, disasters further weaken fragile points along the medical supply chain. Noé predicted that if Houston—a major hub for the petroleum industry—sustained significant damage from Hurricane Harvey, the resulting increase in petroleum prices and interruption in resin transport could spell trouble for BD. “If we didn’t prepare for it, we may be running out of raw material to be able to build certain plastic components which go into medical devices, which could lead to a shortage,” he explained. He recalled that as Hurricane Katrina bore down on New Orleans in 2005, BD maintained dozens of rail cars full of polypropylene pellets out of the storm’s path in Kansas City, ready to be moved to manufacturing facilities.

Hurricane Harvey could also cause a spike in orders for syringes, needles, and medical devices to replace those destroyed by flooding, Noé observed. “There will be a huge surge in demand which will . . . lead to rationing,” he predicted—not just during the storm’s immediate aftermath, but long afterward. “It took us almost 18 months to recover from our

H1N1 pandemic [surge],” he recalled; that is, for BD’s product supply to return to steady-state levels. Meanwhile, he noted, elective surgeries in the United States declined by nearly half. “That was just H1N1, so we can only imagine what would happen in the event of something else,” he continued. “The system is not resilient.”

Neale described challenges to international medical supply distributors responding to infectious disease pandemics in countries that lack public health infrastructure. During the West African Ebola epidemic of 2014–2016, she said, Henry Schein sent a supply of gloves and masks worth $1 million to Liberia, where they were rejected, because the country’s real need was for PPE. As the crisis rapidly unfolded, complications with customs and purchasing delayed delivery of desperately needed supplies. The United Nations Children’s Fund’s (UNICEF’s) pandemic response teams received air shipments of unlabeled boxes, the contents of which had to be sorted to separate useful contents from useless items that had to be destroyed—which in itself was a challenge, she added.

In response to this tragedy, Henry Schein and other medical supply companies have joined with UNICEF and other nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), as well as CDC, to form PSCN (PSCN, 2018). PSCN aims to arrange advance purchase agreements in order to expedite the delivery of medical supplies to any community experiencing an outbreak of disease with severe pandemic potential.

Davidson observed that natural disasters often interrupt deliveries to retail pharmacies, and also limit patient access to stores and pharmacies.

Right now in Texas . . . we can’t get to the stores or get to the area that’s affected . . . a lot of responders are sitting in North Texas waiting for the rain to stop as the water rises, and you’ve got people [who need medication who] can’t get to their pharmacy. We may have [staff] in those pharmacies; they may be open because [their staff] ended up spending the night there, and that’s usually what happens . . . but the problem is the people can’t get to . . . their needed medications, and we can’t resupply them, because we can’t get into the area.

In such situations, she noted, Walgreens works with state and federal officials to ease prescription regulations, as described below.

Repercussions of Supply Chain Failure

“If there’s a failure in the supply chain for whatever reason,” Runnels asked the panelists, “what’s at risk, what’s at stake, what do you have to lose?”

“Our reputation,” Davidson replied. Customers expect their local pharmacy to be able to provide them with their medications, no matter

what, so Walgreens’s reputation is at stake if they cannot help their patients in an emergency. “If there is some type of pandemic they would want their pharmacist to give them their immunizations, because that’s where they go now for the flu vaccine,” she observed, and pharmacists also serve their communities as providers of advice.

“Nearly 2 million physicians, dentists, and veterinarians depend on [Henry Schein] to get the product that they need, and if we can’t deliver we’ve failed them and we’ve failed the patients that they serve,” Neale said. If patients’ health is at risk, she explained, “the trusted relationship with our customers is at risk, and the health of the population is at risk, so there is a lot at stake.”

Emphasizing a private-sector organization’s understanding of the criticality of their role, Noé pointed out, BD’s 18,000 employees are patients as well. “Our relationship is directly line of sight all the way through the system,” he stated—from distributors to retail pharmacies to patients. Profits may come and go, but “in real time it’s about the patient . . . and that you can’t put a dollar amount to,” he added.

ADDRESSING SUPPLY CHAIN GAPS

As the three panelists’ comments made clear, constraints imposed by inelastic inventories significantly limit the ability of medical manufacturers and distributors, as well as retail pharmacies, to respond to emergency surges in demand. In considering how to overcome these limitations, panelists and other workshop participants focused on improving information sharing, coordination, and communication across the supply chain and between public and private sectors.

Public–Private Coordination

Noé acknowledged that BD’s government affairs staff have only recently participated in open conversations with DSNS. Sharing information, developing playbooks, and discussing communication processes are new to the manufacturer, which previously engaged solely in contractual discussions with federal agencies involved in emergency preparedness. Talks aimed at anticipating demand and establishing advance approvals for the emergency use of alternative products under crisis conditions are also under way, he said.

Walgreens attempts to redistribute product throughout their internal supply chain when public health emergencies are expected to create shortages at individual retail pharmacies, according to Davidson. For example, products likely to be in short supply in Texas in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey will be shipped from elsewhere in the country. “Our trigger [to

respond to such situations] is the declaration of [a] state of emergency, or some type of contact to our . . . Security Operations Center,” she explained. The Center then works closely with its distributor, ABC, to move critical items to stores in affected areas. “We have an entire playbook that outlines exactly what to do,” she said. For example, if a state of emergency is declared in Texas, pharmacists can refill prescriptions for up to 30 days for maintenance medications such as blood pressure and cholesterol drugs. Because Texas was proactive in declaring the state of emergency for Hurricane Harvey, Walgreens had adequate time to consult historical monthly inventories in Houston-area stores and work with ABC to align inventory with projected demand, she reported. Walgreens’s government relations team is working to raise emergency prescription refill limits to 30 days in every state, she added; some states limit emergency refills to as few as 7 days’ supply.1 She noted that her office works closely with the HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary of Preparedness and Response (ASPR), especially during emergencies.

Davidson stressed the importance of strong communications—both internally and with ABC and other business partners—and creativity in avoiding regional supply imbalances, including during normal flu seasons. District managers and pharmacists sometimes drive flu vaccine and syringes to stores where they are in short supply, she reported. “It is very hard to predict what the need is in each store,” she explained. “We base it on last year’s numbers, but [demand] always goes up, and it always changes . . . and you try not to stockpile because you don’t want to create a shortage, but you also have to be very mindful of what is going on” in terms of regional demand.

Additional legal measures—beyond refill extensions—ease standard restrictions on pharmacists during states of emergency in some jurisdictions, allowing them to dispense medications by protocol to physicians or to patients by standing order, Davidson noted. For example, pharmacists in an area experiencing a flu epidemic may be permitted to dispense Tamiflu to children without a prescription who meet symptomatic criteria and whose parents sign a waiver. Walgreens has established memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with some states and even companies to dispense antibiotics and other medications on an emergency basis, she reported. Such agreements anticipate the need for emergency measures, avoiding problems such as the need to change prescription limits after a state of emergency is declared.

Albert J. Romanosky is the medical director and state emergency pre-

___________________

1 Some states limit the supply of emergency refills even further to 72 hours. For more information about emergency prescription refill laws by state, visit https://www.healthcareready.org/blog/state-emergency-refills (accessed January 24, 2018).

paredness coordinator in the Office of Preparedness and Response for the Maryland Department of Health. Romanosky remarked that Maryland has instituted a similar emergency prescription protocol to address the opioid epidemic. Because Maryland’s deputy secretary of public health signed a standing order for naloxone (a medication used to rapidly reverse an opioid overdone) dispensing, anyone can request that drug from any pharmacy in the state without a prescription, and without the need to demonstrate a medical indication, he explained.

Linda Rouse O’Neill, vice president of government affairs for HIDA, described her organization’s establishment of two groups—one focused on sterile gloves, the other on hypodermic needles—composed of representatives of manufacturers who share data with the goal of ensuring that the SNS maintains an adequate supply of these vital products. “We’ve actually got competitors . . . on the phone together sharing data, [and] getting that validated by the science team at the SNS to make sure that the products that we’ve got and the descriptions that we’ve got are going to meet the needs for the various scenarios that they’re planning for,” she stated.

McKesson Corporation, a third-party distributor, is currently creating databases of annual sales for needles and gloves, based on information supplied by HIDA members, O’Neill reported. These are only two of thousands of products that could be evaluated through the same process, providing DSNS with real-time snapshots of the contents of the commercial market for many stockpile assets, she noted. HIDA is developing a playbook to operationalize that process.

O’Neill predicted that inventories of many SNS assets will prove insufficient. The ability to characterize potential shortages and their causes represents an important first step toward filling supply chain gaps, she observed. “Our goal was to give [DSNS] . . . really good data [on] what’s truly in the market, and what we could surge if we need to,” she explained, to help the SNS determine whether it should expand inventories of specific finished products or raw materials. Noé said this effort should aid critical decision making by the SNS, and the businesses that supply it, in advance of situations that require tough choices, such as the rationing of health care.

For its part, DSNS intends to institutionalize the analysis of real-time supply chain data, and to create playbooks based on these findings, Greg Burel stated. He reported that DSNS has also entered discussions with the Healthcare Supply Chain Association, which represents “downstream” group purchasing organizations for hospitals and other medical facilities (HSCA, 2018). Those conversations have focused on problematic surge responses in the retail sector such as phantom demand and double ordering (a cause of shortages during surges and depressed demand afterward).

Burel expressed hope that its joint efforts with the private sector to gather data on the global medical supply chain would help persuade fed-

eral leaders to recognize and support the expanding role and importance of the SNS. He also encouraged medical manufacturers and distributors to increase elasticity along the supply chain in order to fill specific gaps identified in surge-simulating tabletop exercises conducted with HIDA. By the same token, he noted, DSNS is now aware of the problems faced by manufacturers regarding phantom demand and double ordering, and is exploring ways to reduce those risks through remedies such as purchase agreements. “I have no evidence to say we’ve done anything that’s going to directly increase supply chain elasticity,” he acknowledged, but he hoped their efforts had at least raised awareness of the problem of the lack of flexibility in the supply chain among those, including policy makers, who could help to address it.

Neale emphasized the importance of sharing information among public and private participants in the global medical supply chain, and acknowledged the Standing Committee for its role in fostering such exchanges. “So [many] of the issues and details discussed in these meetings and [through] these platforms [are] proprietary, confidential, corporate information,” she noted; by providing a space through which the information could be shared, the Standing Committee made an important contribution to public health security.

International Coordination

In the same spirit as HIDA’s efforts to inform domestic emergency preparedness, PSCN connects key manufacturers and distributors of medical products with the World Food Program, the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF, CDC, and the World Bank to support coordinated responses to 10 high-priority infectious diseases, Neale reported. As previously noted, PSCN was created in the shadow of the disorganized international response to the recent West African Ebola epidemic.

Since its inception in January 2015, PSCN has focused on developing long-term advance purchasing arrangements for 62 products identified by the network’s health organization partners as essential to pandemic response, Neale stated. These purchasing agreements will be pre-vetted and arranged through the United Nations Global Marketplace (UNGM, 2018). Under this plan, UN agencies would be the first buyers of the designated products, she explained; national governments would then purchase the products through the UNGM. “This would be a platform where the demand and the supply can meet, and [because the products are pre-vetted], purchasing can happen much more freely,” she said.

PSCN is also developing an early warning system that will enable WHO to alert the rest of the network when crises arise, Neale said. However, she added, determining when to activate private-sector partners to shift to surge

production, and thereby risk triggering irrational buying along the supply chain, has proved challenging—a challenge that DSNS doubtless faces as well. That these discussions are happening at all is a major step forward, she noted, but the next major step is even more daunting: governance. Although PSCN’s partners have come together and built relationships with “incredible trust,” she said, the network lacks a structured government, and must create one in order to implement the UNGM.

Davidson noted that Walgreens is an international company through its recent alliance with Boots UK, which has distribution networks throughout Europe and South America (Walgreens Boots Alliance, 2018). Boots and Walgreens have worked together and with WHO on several international projects, including supplying vitamins and immunizations to children in developing countries. “Those types of synergies are very important in today’s marketplace,” she concluded.

Importance of Communication

A lack of reliable information along the supply chain exacerbates gaps during a surge, Noé observed. In the midst of a public health emergency, buyers seeking essential products can be confused or misled by the overabundance of information—some of it inaccurate or conflicting—that they encounter online. Thus, he said, BD works with distributors of its products to ensure that the health care providers they serve are receiving accurate information about product availability and possible alternatives in the event of shortages—and to ensure that providers communicate their needs up the supply chain.

Likewise, DSNS is working to educate public health agencies and health care providers about the stockpile’s mission and operation, Burel reported. It has taken seminal events like Ebola to show that the SNS is not just “pills on shelves,” but rather a participant in the medical supply chain, and therefore subject to trade and other economic forces, he said.

Karen Remley, executive director and CEO of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), noted that the security of the supply chain upstream of the SNS depends on trade relationships with countries such as Malaysia (which, as previously noted, supplies 90 percent of the world’s latex for gloves). Higher levels of government—including the Department of State and federal economic advisors—need to be made aware of the significant impact of trade negotiations on emergency response, she stated.

Tara O’Toole reiterated that a significant portion of PPE comes from China, and a substantial proportion of surgical instruments are also made in Mexico. Trade policies will determine the availability of these and many other critical products and raw materials, she observed. Because bipartisan congressional support for public health preparedness remains strong, she

suggested, “maybe we need to do some strategic visits on [Capitol] Hill with some of those committees,” referring to the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP), and others that focus on related issues.

Irwin Redlener, professor of pediatrics and health policy and management at the Mailman School of Public Health and director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University, emphasized that a secure supply chain both contributes to and relies on the larger national agendas of global health diplomacy and security. “Disruptions to relationships with Malaysia, with Pakistan, with Mexico are extraordinarily nuanced, but critical,” he remarked, and advocated for direct conversations with appropriate Department of State representatives to address this topic.

O’Toole noted that the consequences of gaps in the global supply chain reverberate across multiple industries. “I am seeing it in my own job in software, where the software for our new jet fighters is being written in China, and a lot of the hardware is being made there as well, which raises national security concerns,” she stated, and suggested that the problem of supply chain security is ripe for analysis by the National Academies.

For the near term, O’Toole encouraged Standing Committee members to become “fonts of wisdom and advocacy” on the issue of medical supply chain security and its consequences for every American, and authors of editorials on that topic, particularly given the teachable moment presented by Hurricane Harvey.

This page intentionally left blank.