2

Creating a Culture of Well-Being

“WHAT BRINGS YOU JOY?”

Much of the ongoing conversation about the well-being of health professionals focuses primarily on stress and burnout, said Kreitzer. However, she said, perhaps a better perspective would be to focus on creating a culture of well-being by proactively helping people to find joy in their work. Looking at an issue through a different lens, said Kreitzer, leads us down a path toward different types of solutions. Asking “Why are people leaving and why are they turning over and why are they stressed and burned out?” will lead us down one path for addressing well-being, said Kreitzer. But asking people “What brings you joy?” can lead us down a path that is ultimately more positive, fruitful, and sustainable, she said. According to Kreitzer, an organization whose leadership promotes a culture of wellbeing will be more resilient, more capable of handling change, and more responsive to the needs of their employees.

Ted Mashima, planning committee member and moderator of the session, opened with a quote often attributed to Peter Drucker: “Culture eats strategy for breakfast” (Campbell et al., 2011). He explained that specific strategies for improving performance at an organization are far less effective than a cultural shift that supports optimum performance and well-being. Creating a shift in culture requires persistence, optimism, and leadership. Workshop participants heard from several speakers who have been part of a cultural shift at their organizations.

INTERPROFESSIONAL COMPASSIONATE CARE

Dorrie Fontaine, University of Virginia

In 2009, Dorrie Fontaine, dean and professor at the University of Virginia (UVA) School of Nursing, spent 8 days at Upaya, a contemplative retreat in New Mexico, along with other health professionals from UVA. The focus of the retreat was end-of-life care, and in the years following the retreat, workshops were held at UVA to introduce students and professionals in multiple disciplines to a contemplative perspective toward caring for those at the end of life. In 2013, the Compassionate Care Initiative (CCI) was established at UVA (2018) in order to:

cultivate a resilient and compassionate healthcare workforce—locally, regionally, and nationally—through innovative educational and experiential programs … and to have safe and high functioning health care environments with healthy and happy health care professionals and where heart and humanness are valued and embodied.

CCI’s programs seek to create compassionate and resilient leaders that will in turn create compassionate and resilient workspaces, said Fontaine. Teaching today’s students to focus on self-care and compassion will, it is hoped, “create an army of really compassionate patient care providers,” she said. While it is situated within the school of nursing, CCI is an interprofessional effort, with programs by and for people in multiple health professions, said Fontaine. In fact, at UVA, all third-year nursing and medical students are trained together in order to create understanding of each other’s roles. Programs offered through CCI include resilience retreats; yoga, meditation, and tai chi practices; and lectures, simulations, and discussions on topics such as listening, connection, and engaging with patients. A recent evaluation of CCI found that nurses who trained in CCI at UVA were more likely to practice meditation, exercise, yoga, breathing exercises, and writing, compared to nurses who trained at other schools (Cunningham et al., 2018). While there is not yet any formal evaluation of the program’s effect on patient care and engagement, Fontaine noted that preliminary data about nurse self-care is encouraging.

One of the most well-known initiatives to come out of UVA is called “the Pause,” in which health care providers join together in a moment of recognition and reflection after losing a patient. Jonathan Bartels, a nurse affiliated with CCI, created the Pause as a way for health providers to acknowledge their own hard work and the life of the person that was lost. Working as a trauma care nurse, he had noticed that after a death, he and his colleagues would just “rip their gloves off and go out in the hallway to more patients,” with no chance to process what had just happened or to

reset themselves to get back to work. The Pause has spread far and wide; it was first picked up by other UVA departments and now exists in nearly 100 hospitals on four different continents, said Fontaine. She also described reaching across sectors where her students have enrolled in classes on design thinking for compassion through architecture. Through the use of design thinking in clinical practicums and elsewhere, said Fontaine, people are changing the way they look at aspects of routine practices.

After Fontaine’s presentation, Aviad Haramati, a member of the planning committee, asked her what the levers were that allowed the culture at UVA to shift. More specifically, Haramati asked, “What was the key there? Was it you walking the walk? Was it getting the opinion leaders? Was it the transformative experience?” Fontaine answered that the key element was “making friends and colleagues and having a generous spirit.” She explained that upon arriving at UVA, she made an effort to be visible and to get to know everyone on campus. To fund the program, she reached out to alumni, donors, foundations, and others. Fontaine said instead of programming based on the money that was currently available, she decided what she wanted to do and found the money to do it. She joked that her optimism was genetic; her mother used to say “Anyone can have fun in the sun!” when the family was out “picnicking in the pouring rain.” Fontaine explained that she wants to institute an “epidemic of optimism” instead of focusing on the costs and barriers to implementing these types of programs.

DESTIGMATIZATION FROM THE TOP: MIND MATTERS

Lizzie Lockett, Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons

Lizzie Lockett, Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) in the United Kingdom, first explained how the unique structure of her organization allows her to work on shifting culture. The principal function of the RCVS is as a statutory regulator, but it also is a royal college, so it can advance standards of the profession and “enable veterinary surgeons and veterinary nurses to be the very best that they can be,” Lockett said. Unlike pure regulators, the RCVS was set up by a charter giving them the latitude to be more innovative in how they engage with their constituency through leadership and other strengthening efforts for the profession, such as the RCVS’s mental health initiative.

Lockett said that within the veterinarian profession in the United Kingdom, there are high levels of poor mental health. This is caused by high levels of stress and has unfortunately led to a number of veterinarians taking their own lives. Various factors contribute to and exacerbate this situation, she said. There is stigma around mental health in the profession, with veterinarians wanting to be “in control of the situation” and not “show weak-

ness,” said Lockett. Many veterinarians are isolated, either geographically or in terms of working on their own as consultants, without colleagues to talk to. Veterinarians also have access to medications that can enable them to take their own lives. Lockett emphasized how the RCVS can encourage veterinarians and veterinary nurses to take steps to address their own mental health, but a lack of awareness and resources, as well as stigma, make it unlikely that people can or would do it on their own.

The RCVS has set day one competencies—things they expect new graduates to be able to do—in the area of mental health. First, they must “understand the economic and emotional context in which the veterinary surgeon operates” and “know how to recognize the signs of stress and how to seek support to mitigate the psychological stress on themselves and others.” Second, students are required to “demonstrate ability to cope with incomplete information, deal with contingencies, and adapt to change.” Lockett noted the challenges faced by anyone trying to attain these mental health competencies could be particularly daunting for new graduates to meet, so the RCVS has developed assistance programs like those situated within their Mind Matters Initiative.

The Mind Matters Initiative was launched in 2015, with funding of £1 million over 5 years. Part of the funding goes to one-on-one support for individuals, which is carried out at arm’s length by independent charities, while the rest is used to develop tools, techniques, trainings, and campaigns to address mental health and wellness. Recently, RCVS has paired up with the American Veterinary Medical Association to promote the project internationally. The campaign currently consists of about 30 different interventions, with three main work streams focused on prevention, protection, and support (see Figure 2-1).

SOURCE: Presented by Lockett, April 26, 2018.

Lockett noted that while it is critical to help the people who are currently struggling with mental health problems, efforts must be made to change the systems to prevent people from developing mental health problems in the future. To do so, the “prevent” work stream looks at issues, including

- How are veterinary undergraduates prepared for their work? Do their expectations of work and the realities match?

- What factors are causing stress in the workplace? Which of these factors can be changed?

- How can veterinarians be supported in the workplace with strong social networks?

While these types of systematic changes are under way, the campaign also focuses on giving individuals the skills and tools they need now to protect themselves from stress and burnout, while also providing organizations the tools they need to improve.

The “protect” work stream is developing mental health awareness training courses, online mindfulness courses, and specific courses for managers on how to support others while staying healthy themselves. The “support” work stream helps individuals who are currently dealing with mental health issues, which is done through a separate charity organization. According to Lockett, a key element of Mind Matters is the partnerships between a wide variety of stakeholders representing students, educators, practice managers, nurses, business owners, and others.

One particularly successful Mind Matters program is called “& Me,” said Lockett, that focuses on destigmatizing mental health within the veterinarian profession. She quickly added that destigmatization requires shifting the culture; it cannot be done through simple one-off programs or education. Destigmatization will only occur if people “feel the organization really lives and breathes” the commitment to mental health, and when there are “spaces where people can feel they can talk about their mental health and their stress.” Lockett explained that one essential component of destigmatizing mental health is having senior leaders within the profession talk openly about their own mental health. The “& Me” program, run jointly with the Doctors’ Support Network in the United Kingdom, seeks to do this through presentations by leaders from both the human and veterinary medical professions who have “struggled with their mental health, who were now flourishing, who could give the idea that a diagnosis doesn’t determine the rest of your professional career.” For example, veterinarian David Bartram, a “rock star” researcher in mental health in the veterinary profession, shared his own story about mental health: “I firmly believe that had I confided and sought help early, I would not have become unwell.

Don’t worry that disclosure may affect your career. It should not, and your health must come first” (Mind Matters, 2017). The program holds events but primarily runs online messages through social media, sharing stories about leaders and inviting discussion and comments. The leaders who have shared their stories have found support online and in person, and have been praised for coming forward, said Lockett. The campaign has been extended to include a student-led activity called “Failure Fridays,” in which senior people in the field talk about instances where they experienced failure and how they moved on.

In conclusion, said Lockett, the campaign is about “hope, taking personal responsibility, showing senior leadership, the power of collaboration, and encouraging help-seeking behavior.” She further noted the campaign’s cost-effective programs that rely predominantly on volunteers to offer their stories, and an online platform for a majority of their outreach. She closed with messages to the diverse audience saying efforts are under way to extend the campaign to other health professions, as well as to other countries.

EVIDENCE-BASED TOOL FOR CHANGE: THE HAPPINOMETER

Sirinan Kittisuksathit and Charamporn Holumyong, Mahidol University

Sirinan Kittisuksathit, associate professor at the Institute for Population and Social Research at Mahidol University in Thailand, introduced workshop participants to the “Happinometer,” an evidence-based tool that was developed to help organizations measure and improve their employees’ happiness (Institute for Population and Social Research, n.d.). The Happinometer measures nine different dimensions of “Happy”:

- Body

- Relax

- Heart

- Soul

- Family

- Society

- Brain

- Money

- Work–life balance

These dimensions were chosen and developed by a committee of multidisciplinary experts in quality of life, well-being, happiness, and mental health, said Kittisuksathit. The committee drew on a breadth of theoretical constructs and research, including Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (1954) and the World Health Organization Quality of Life (2018). The Happinometer was tested for validity and reliability on all nine dimensions. The Happinometer is like a thermometer for measuring happiness, said Kittisuksathit. After happiness is measured, unhappy dimensions can be identified, and activities can be developed and implemented to reduce unhappiness.

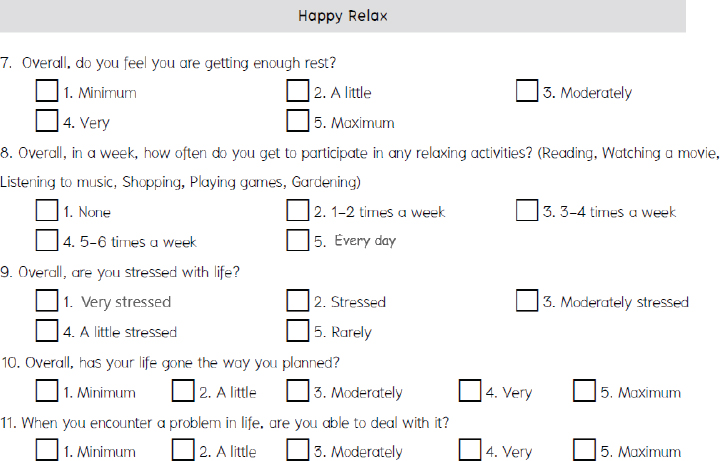

More than 5,000 organizations—including both governmental and private, small and large—and 1,000,000 individuals have used the Happinometer. When an organization commits to using the Happinometer, the organization’s staff completes the questionnaires, which are available on paper, online, or in a mobile app, and in 10 different languages. The resulting happiness levels can be presented individually or as organizational averages. Additionally, happiness levels can be assessed on a national level; these data can be used to identify where citizens could use some help and to measure changes over time. The Happinometer was first used to measure national happiness in Thailand in 2012. The lowest dimension was Happy Relax (see Figure 2-2), while the highest dimension was Happy Soul, said Kittisuksathit.

SOURCE: Presented by Kittisuksathit and Holumyong, April 27, 2018.

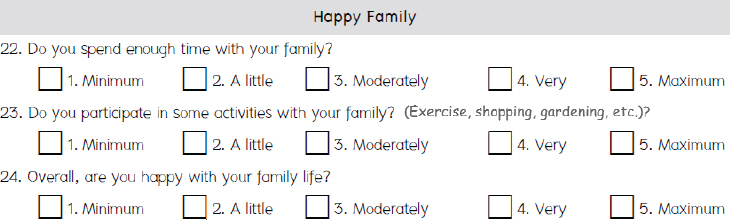

Kittisuksathit said that when they first developed the tool, they could diagnose happiness levels but did not have a method to improve happiness. They developed a curriculum called Routine to Happiness (R2H), which is used to identify and train “happiness agents.” These agents are trained to manage and evaluate the data from the Happinometer, and to develop a Happiness Action Plan for happiness activities. To make a Happiness Action Plan, one must identify an objective for the activity and a target population, specifying desired outcomes, budget, time, and process. Kittisuksathit gave an example of a Happiness Action Plan for an activity to improve Happy Family (see Figure 2-3). The activity would be conducting events for families to walk and run together. The short-term output measure would be “number of employees who took their family members to join the events.” The medium-term outcome goal would be an increase in the average score on Happy Family, and the long-term goal would be an increase in the average overall happiness score. The happiness agents can develop and implement these action plans, and are trained in monitoring and evaluation so they can assess the effectiveness of the plans.

After Kittisuksathit’s presentation, she and her colleague, Charamporn Holumyong, assistant professor at Mahidol University, led workshop participants in an interactive session. Participants were given a set of data on a hypothetical organization, similar to what happiness agents work with, and asked to identify an area for improvement and to develop an idea for an activity. For example, the individual participants in the group that was assigned Happy Body noticed that about three-quarters of people reported exercising less than three times per week. To increase employees’ physical activity, the participants in the group decided that the organization should offer a fitness center, and should also encourage physical activity through incentives such as a day off for people who logged the most minutes of activity. Holumyong noted that when developing activities, it may be important to consider the age, gender, or culture of employees to find activities

SOURCE: Presented by Kittisuksathit and Holumyong, April 27, 2018.

that are most appropriate and effective. This is why, she said, it is critical to have happiness agents from inside the organization, rather than using outside experts. Internal happiness agents know and understand the culture of the workplace and can design the activities for the needs of the organization and its employees. Talib noted that this is a similar concept to the design thinking approach—that the people who are most affected by an organization’s culture and policies are the ones best suited to find ways to change it.

UNIVERSAL CARE IN THAILAND

Rajata Rajatanavin, Former Minister of Public Health in Thailand

In 2002, Thailand began offering universal health care coverage to its population, said Rajata Rajatanavin, former minister of public health in Thailand and former president of Mahidol University. Thailand has a population of 68.9 million, and spends about 4.6 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health care, in contrast to the United States, which spends around 18 percent of its GDP on health care (World Bank, 2015). There are two reasons why Thailand can offer universal care, said Rajatanavin. First, Thailand has an extensive infrastructure of health care. The country is divided into provinces, districts, and subdistricts. Each subdistrict covers around 3,000 to 5,000 people, and has one primary care center. Each district has a hospital for secondary care, and each province has at least one provincial hospital for tertiary care. Finally, there are regional hospitals that provide quaternary care. Second, said Rajatanavin, Thailand produces its own doctors, nurses, and other health care workers, and can also provide wide varieties of subspecialty training in the country.

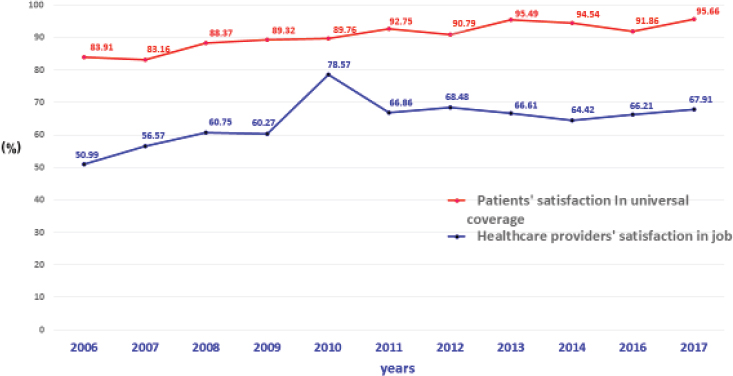

Patients are overwhelmingly satisfied with universal coverage in Thailand, said Rajatanavin. As shown in Figure 2-4, satisfaction in 2006 was at 83 percent, and was at more than 95 percent in 2017. This is in contrast to health care providers whose satisfaction in their jobs was not high. In 2006, 50 percent of providers were satisfied, which increased to 67 percent in 2017 (National Health Security Office, 2018). Rajatanavin said he is “not surprised” by these numbers, because when patients enjoy increased access to health care, this means an increase in workload for providers. Investigators found one particularly stressful component of work for medical providers is the number of hours they are required to work as medical interns. After graduation, medical students in Thailand must spend 3 years working as interns in rural areas before they are eligible to do further specialty training. These interns—who learn in secondary, tertiary, and university hospitals—work a huge number of hours, said Rajatanavin. Around 60 percent of interns work more than 100 hours per week, with about 10 percent working more than 140 hours per week (Buppasiri et al., 2012).

SOURCES: Presented by Rajatanavin, April 27, 2018; National Health Security Office, 2018.

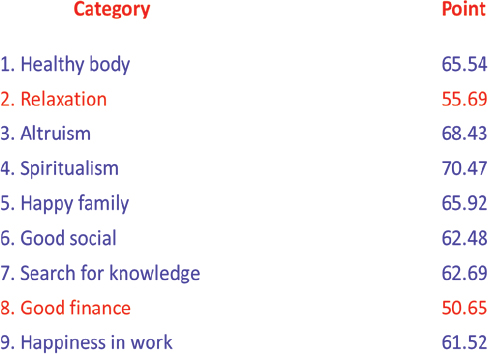

Rajatanavin described several steps that were taken in recent years to alleviate this problem, and to strengthen the medical system as a whole. First, the Ministry of Public Health focused on improving primary health care, so people received medical and preventative care close to home, rather than ending up in a distant hospital. Second, the Ministry of Public Health issued a policy that every hospital in the country must have a palliative care program. According to Rajatanavin, there is an aging population in Thailand that is in need of better care for chronic disease and terminal illnesses. Third, the Thai Medical Council announced that interns should not work more than 40 hours per week. This is an announcement, not a directive, said Rajatanavin, but it is a good first step toward fixing the problem. The fifth and final step was a 20-year plan launched by the Ministry of Public Health to strengthen the health workforce. The plan included cultivating a culture of core values; strengthening human workforce potential in the areas of business, management, leadership, and professionalism; plotting a road map for organizational happiness, including a new Chief Employee Experience Officer; and using the Happinometer to measure and improve happiness in the workforce. Figure 2-5 shows the results of the Happinometer survey from the Ministry of Public Health staff in 2017, where the leadership found that the staff scored lowest on Happy Relax and Happy Money.

SOURCES: Presented by Rajatanavin, April 27, 2018; Thailand Ministry of Public Health, 2017.

REFERENCES

Buppasiri, P., P. Kuhirunyaratn, P. Kaewpila, N. Veteewutachan, and J. Sattayasai. 2012. Duty hour of interns in university hospital and hospital in ministry of public health. Srinagarind Medical Journal 27(1):8–13.

Campbell, D., D. Edgar, and G. Stonehouse. 2011. In Business strategy: An introduction. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. P. 263.

Institute for Population and Social Research. n.d. Happinometer. http://www.happinometer.ipsr.mahidol.ac.th (accessed June 29, 2018).

Maslow, A. H. 1954. Motivation and personality. New York: Harper & Row.

Mind Matters. 2017. David Bartram’s speech––House of Commons &Me launch 31 January 2017. https://www.vetmindmatters.org/david-bartrams-speech (accessed June 27, 2018).

National Health Security Office. 2018. Report of 2017 survey of public, providers and related agencies’ satisfaction of universal health coverage. Bangkok, Thailand: National Health Security Office.

Thailand Ministry of Public Health. 2017. Report of the survey of quality of life, happiness, and organization engagement of personnel of Ministry of Public Health. Bangkok, Thailand: Thailand Ministry of Public Health.

UVA (University of Virginia). 2018. About. https://cci.nursing.virginia.edu/about (accessed June 27, 2018).

World Bank. 2015. World development indicators. http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/ world-development-indicators (accessed August 10, 2018).

World Health Organization. 2018. The World Health Organization quality of life. http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/whoqol/en (accessed June 27, 2018).

This page intentionally left blank.