2

The Path to a High-Quality Future: The Need for a Systems Approach and a Person-Centered System

Do we fix the way the system works, or do we change the way we think about health care?

Achieving high-quality health care is a complex pursuit in any setting, even one with rich resources. However, it is particularly difficult, and arguably more important, for low-resource settings. As demonstrated in Chapter 1, many challenges to achieving high levels of quality care still exist worldwide, leading to fragmented and undesirable patient journeys. Improving the patient journey requires an integrated system of care and productive interactions among many system levels—both public and private.

Given the complexity of the interactions involved, the pursuit of excellence in health care depends deeply on systems thinking—a perspective that draws on the sciences of sociotechnical systems and human factors, among others. This chapter first outlines the committee’s commitment to systems thinking as foundational for high-quality care, and calls for a health system that is consciously designed and continually improved to optimize the interactions between people (patients and providers) and the tasks, technologies, equipment, and organization of health care that are essential to the pursuit of quality. Given that the results achieved by any system depend on its design, the committee then presents 13 general principles to help guide the design of a person-centered health system in any setting. This section also presents real-world examples of these principles in action, and how they can influence a more person-centered health care system. The final section presents a summary and the committee’s first recommendation.

THE NEED TO REDOUBLE EFFORTS FOR A SYSTEMS APPROACH

In response to the fragmentation of care described in Chapter 1, models of integrated care have been proposed with the promise of providing safer (Vincent and Amalberti, 2016), more effective and efficient (Armitage et al., 2009), and more person-centered care without sacrificing health outcomes (Mason et al., 2014). However, such integration efforts have had mixed results, possibly because of how they have been structured. Instead of seeking to improve outcomes and the patient experience, integration in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) often focuses on structural and process issues, such as increasing access, increasing uptake of services, clustering services for specific populations, and improving resource efficiency (Mounier-Jack et al., 2017).

LMICs would benefit from a greater focus on the pursuit of services that are integrated and that emphasize the patient experience, as stressed by the World Health Assembly in its call for strengthening integrated, people-centered health services (WHO, 2015). Success in this pursuit requires that support systems, such as information, finance, contracting, and training, work in harmony. This means that LMICs need to integrate not

only services but also these support systems, which can be a more difficult undertaking. However, if LMICs take full advantage of ongoing trends of interprofessional education, collaborative practice, task shifting, and community health care, they are in a strong position to succeed with this type of integration (Mounier-Jack et al., 2017).

To integrate care, optimize the patient journey through the health care system, and thereby improve health care quality, all countries will need to apply a systems-thinking perspective. Systems thinking has long been embedded in other sectors, such as manufacturing, transportation, construction, and engineering. This approach has been discussed and sometimes attempted in high-income countries, but few health systems have been able to execute it at full scale as designed to realize its full potential. The U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM) defined a systems-thinking perspective for health care as follows:

A systems approach to health is one that applies scientific insights to understand the elements that influence health outcomes; models the relationships between those elements; and alters design, processes, or policies based on the resultant knowledge in order to produce better health at lower cost. (Kaplan et al., 2013, p. 4)

This definition acknowledges that systems outside of health care also strongly affect the health of a population, and that each system component needs to be optimized not only in isolation but also in conjunction with others lest “suboptimization” of individual elements degrade the care provided by the system as a whole. Although the call for a systems approach to health care made in Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001) did influence various efforts to mesh systems engineering and health care—such as the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) analytical guide to the use of systems thinking to strengthen health systems (WHO, 2009)—the execution of this approach remains a work in progress for all countries. Thus, there is a need to renew systems thinking to better integrate care worldwide and optimize the patient journey for high-quality care.

Systems Thinking for Health Care

While much conceptual work has applied systems thinking and systems principles to the health care field, most interventions to date have focused on increasing access, improving training, instituting financial incentives, and a few other targeted efforts. By neglecting to take a holistic perspective, such interventions fail to address the underlying issue behind poor quality: poorly structured organizational contexts and process inefficiencies that interact with each other and at multiple levels (e.g., country, region, com-

munity, hospital). If ignored, these interdependent upstream factors degrade the provider–patient interface, leading to poor outcomes.

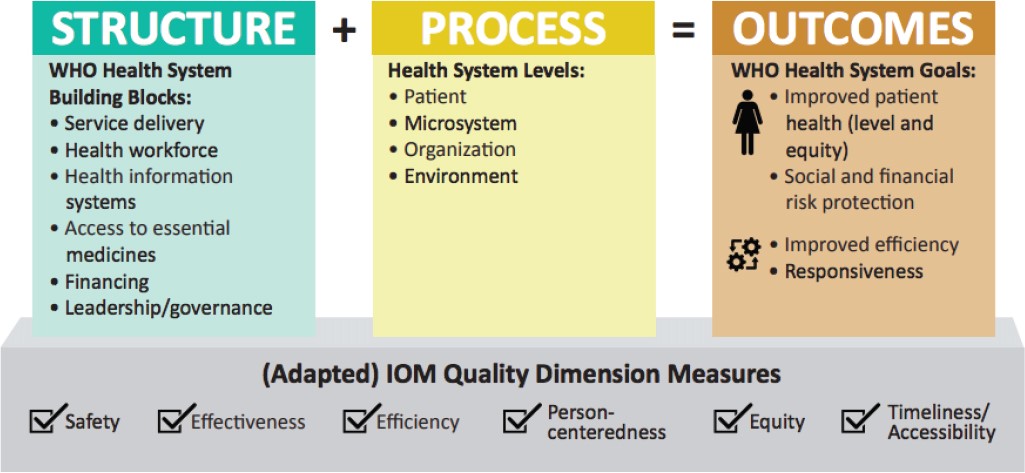

The importance of systems thinking is reflected in Figure 2-1, which integrates the prior conceptual frameworks on which the committee drew: Donabedian’s (1988) Structure-Process-Outcome (SPO) model; WHO’s (2010) health system building blocks; Berwick’s (2002) health system levels; WHO’s (2010) health system goals; and the (adapted) six dimensions of quality care from Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001). Chapter 1 describes these frameworks in greater detail. Donabedian’s SPO model is placed at the top of the figure to provide an overarching structure for all of the frameworks. The WHO health system building blocks measure structural inputs, Berwick’s health system levels address issues of process, and the WHO health system goals on the right side of the equation can be used to measure outcomes for both the system and the user. In accordance with a systems-thinking perspective, the adapted IOM quality dimensions are characterized in the figure as cross-cutting, suited for use in measuring the structure, process, and outcomes of health care quality. The committee encourages nations and leaders seeking to improve the patient journey to adopt the systems thinking approach, viewing health care as a sociotechnical system and accounting for the emerging field of human factors and ergonomics (HFE), which is discussed below.

Applying Sociotechnical Systems Theory to Improve Quality of Care

Health care delivery relies on people (patients and providers) interacting with technologies in diverse settings and in physical, organizational, and social environments that are influenced by a myriad of policies. Furthermore, health care is not only dynamic in nature but also highly technical. Given the multiple interactions that occur and the highly complex environment in which they occur, a health care system can be characterized formally as a sociotechnical system (Carayon et al., 2011).

Sociotechnical systems theory is an approach used to analyze a complex system or work environment and the interactions among people and organizational structure and processes in this environment. Using a sociotechnical system approach to analyze health care systems can elucidate drivers of health care quality (Chisholm and Ziegenfuss, 1986). First, the approach recognizes that the people involved in health care—patients and all providers—have particular behaviors and limitations, such as competing interests and cognitive loads and nonoptimal health literacy. Second, it recognizes that the technical aspects of a work environment, such as medical knowledge, medical procedures, and electronic health records (EHRs), have a very real impact on people and how they work (Carayon

NOTE: IOM = Institute of Medicine; WHO = World Health Organization.

et al., 2011; Lawler et al., 2011). The end goal of using a sociotechnical system approach is joint optimization for both the people and the organization (Braithwaite et al., 2009). For a health care system, this means that a clinic should

- deliver high-quality health care for patients;

- improve the patient experience;

- provide a high-quality work environment for health care workers; and

- reduce waste for all involved—that is, achieve the “Quadruple Aim” (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, 2014).

The application of a sociotechnical system approach for health care systems can have positive effects on the quality of care. Traditionally, but incorrectly, poor health care outcomes have been attributed to the individual health care worker or health care team. It is for this reason that many quality reform efforts have consisted of positive and negative incentives targeted at the individual provider, such as sanctioning, blame, and training. Such an approach ignores the upstream impacts of organizational deficiencies. Often referred to as the “blunt end” of a complex system, the sociotechnical context can create inefficiencies that cascade down to the “sharp end” of the clinical encounter, manifesting in low-quality outcomes (Cook and Woods, 1994). For example, a design team based at St. Mary’s hospital in London found that doctors were specifying units of a drug incorrectly when writing prescriptions (i.e., micrograms instead of milligrams). To rectify this problem, the design team redrew the form so doctors just had to circle the unit (The Economist, 2018), demonstrating that this “blunt end” change affected the “sharp end” of care. If quality is indeed a systems property affected by decisions occurring at all levels of a health care system, optimizing the system design at all levels should be a priority. This means making a complex system work well for the people within it, which is the object of the discipline of HFE, discussed below. In many low-resource settings, however, the organization or design of the health care sociotechnical system is lacking, leaving front-line health care workers with little support and often trapped in failures not of their making, for which they are unfairly blamed.

It is important to note, moreover, that while understanding and applying sociotechnical system theory as an approach to quality improvement in health care includes identifying what interfaces are weak or when and where processes break down and errors occur, this is only part of the picture. Recently, health care quality experts have been providing additional support for understanding what makes care delivery go well in so many of these complex systems—the majority of the time. Also known as “Safety II,” this new approach is defined as “the ability to succeed under varying

conditions, so that the number of intended and acceptable outcomes is as high as possible” (Hollnagel et al., 2015). In other words, care is delivered in a variety of real-world settings that look nothing like the careful environment of many randomized clinical trials. Many interactions and instances of health care that occur in these environments produce good outcomes, and understanding why these successes happen and how to replicate them regardless of the circumstances can be just as illuminating for quality improvement as understanding why things go wrong. Doing so can assist in achieving “resilient health care,” whereby the system can adjust in response to disturbances to maintain continual and optimal performance. At the same time, however, it must be emphasized that for either approach, understanding human behaviors and incorporating them into systems design and interventions will play a significant role in the quality that results.

Considering Human Factors in Design

To optimize an organization for those within it, considering the strengths and constraints they face is important. A health care system should be designed and structured in a way that makes it easy for patients to access quality health care and easy for providers to deliver such care. Such an approach draws on the field of HFE, which is defined:

the scientific discipline concerned with the understanding of interactions among humans and other elements of a system, and the profession that applies theory, principles, data and methods to design in order to optimize human well-being and overall system performance. (IEA, 2018)

At its core, HFE entails applying knowledge of human behavior, capabilities, and limitations to design systems, tasks, work environments, technologies, and equipment. Its focus, thus, is “on how people interact with tasks … technologies, and … the environment,” with the goal of optimizing human and system efficiency, effectiveness, and safety (NRC, 2011, p. 61). Unfortunately, many health care systems are not designed with these concerns in mind (if, indeed, they are designed at all). They may favor patients at the expense of providers or vice versa, or even show favor to external parties at the expense of both patients and providers. For example, the advent of patient-centered care has led to many interventions that, while ideally beneficial for the patient at the center, fail to respect the limitations of or constraints on providers, often requiring of them additional work and tasks. Similarly, hospitals and clinics can be, and often are, designed and structured in a way that makes care delivery easy for the provider at the expense of the patient. An example is labor and delivery units that fail to meet the real needs of patients and families by imposing restrictions on who

can be in which room at which times, regardless of the mother’s wishes. Likewise, administrative tasks, such as those supported by EHRs, while beneficial in terms of record keeping, can be established for billing purposes and impose an undue burden on both providers and patients.

The Impact of Failing to Account for Human Factors at Multiple System Levels

Although health care journals increasingly appreciate and report on HFE approaches, it often remains difficult to convince funders, clinical decision makers, and managers that HFE assessments should be systematically embedded in clinical practice, clinical trials, and product development (Buckle et al., 2018). Buckle and colleagues argue that the limited application of HFE in health care indicates that the discipline—along with its multidisciplinary methods of evaluation—has yet to be addressed consistently within the national and international health care communities. Incorporation of HFE in health care has positive impacts on patient safety

and the well-being of health workers (Bagian, 2012; Mao et al., 2015). The role of human factors must be considered at all system levels if the patient journey and health care quality are to be optimized at the patient–provider interface. Misalignment of organizational structures and levels can have severe consequences for both patients and providers. Consider, for example, the case study on patient-controlled analgesia pumps in Box 2-1.

The case described in Box 2-1 clearly depicts the dangers of failing to validate medical products with HFE data. Perhaps as a result of safety issues, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued guidance on the application of HFE studies to medical devices (FDA, 2016a), on the use of HFE data in the design of combination products (FDA, 2016b),1 and on which types of devices should include HFE data in pre-market submissions (Hodsden, 2016). Although these are nonbinding recommendations, the issuance of this guidance is a clear indication that regulatory bodies are

___________________

1 A combination product is a product that combines two or all three of a medical device, a drug, and a biologic. An example of a combination product is a drug-eluting stent (Drues, 2014).

recognizing the importance of HFE for medical products. Given the high financial stakes of approval, manufacturers are likely to utilize HFE methods in study designs to verify and validate medical products.

Human-Centered Design and Health Care

Human-centered design is increasingly being recognized in both high- and low-income countries for its benefits to health outcomes and provider satisfaction (Bazzano et al., 2017). The importance of human factors for optimal health outcomes lends credence to the impact of human-centered design on health care. With the application of human-centered design, solutions are tailored to people’s needs while accounting for their implicit cognitive biases (Searl et al., 2010). Maintaining a patient- and staff-focused mindset at the heart of clinical redesign will benefit all relevant parties in a clinical encounter. Human-centered design is discussed in more depth in Chapter 3.

Expanding the Donabedian Model

Although Donabedian’s SPO model (introduced in Chapter 1) highlights the importance of processes for health care outcomes, it does not allow for in-depth analysis of the interactions that occur within a system, nor does it account for the experiences of patients and providers. In response to this gap, the literature on sociotechnical systems has proposed an expanded SPO model—the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model—that captures the interactions that occur in a health system’s structure (termed the sociotechnical “work system” here) and the feedback on the health system’s structure from processes and outcomes (Carayon et al., 2006).

According to the SEIPS model, the elements of the work system are the people (i.e., patients, caregivers, providers), their tasks, the technologies used to perform those tasks, the physical environment in which the tasks are performed, and the context of the organization in which people perform the tasks individually or collectively as members of teams (Carayon et al., 2006). The individual elements of the system need to be designed appropriately—for instance, technologies should follow usability heuristics, or simple rules used to help make decisions (Zhang et al., 2003). However, this is not sufficient. All of the system elements should support, in synergy, the goals of health care quality. This brief example shows how all work system elements need to be considered, especially when implementing any change such as new technology. For instance, technologies that follow

these usability principles should be designed to support tasks performed by people who have received adequate training (organization) and receive help in case the technology breaks down (organization) or malfunctions in a specific physical environment. Interactions among work system elements and feedback from processes and outcomes need to be considered and purposefully designed. For example, health care leaders and policy makers need to consider the following questions when designing the work system to optimize the patient journey and achieve high-quality care (Carayon et al., 2006):

- What are the characteristics of the individual performing the work? Does the individual have the physical, sensory, and cognitive abilities to do the required tasks? If not, can accommodations be made to account for the individual’s abilities so that high-quality work and outcomes are achieved?

- What tasks are being performed, and what are characteristics of those tasks that may contribute to low-quality patient care? What in the rest of the work system allows the individual to perform tasks safely and at a high level of quality?

- What in the physical environment can be sources of error or promote safety and other quality dimensions? What in the physical environment ensures high-quality performance? How does the physical environment (e.g., layout of workspace) support high-quality interactions between people in performing care tasks?

- What tools and technologies are used to perform the tasks, and do they increase or decrease the likelihood of quality care?

- What in the organization prevents or allows exposure to hazards? What in the organization promotes or hinders patient safety and other quality domains?

Following a root-cause analysis of unexpected deaths in the Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), the largest health care system in Qatar, investigators found clear evidence that there had been worsening vital signs, even just hours before cardiac arrest, but that no action had been taken. This is, in part, because the significance of these signs had not been recognized, but also because those that did notice them—often nurses—did not feel empowered to notify physicians. In response, HMC developed the Qatar Early Warning System (QEWS) using evidence-based vital sign charts and a response trigger. Resistance was encountered initially, but because the QEWS prioritized good governance, credibility, and defining training requirements and standard indicators, the program became highly success-

ful and was credited with a 40 percent reduction in cardiac arrest rates (Vaughan et al., 2018).

The crucial roles of sociotechnical systems, human factors, and the interactions within the work system make it clear that to improve the patient journey and health care quality, health care leaders need to build a truly person-centered health system. The people on whom the system is centered need to include not only patients but also providers at all levels of the system.

REDESIGN FOR A PERSON-CENTERED HEALTH SYSTEM

In drafting the design principles presented below, the committee maintained the lens of sociotechnical systems and human factors. The sociotechnical systems literature emphasizes the importance of a methodical approach to designing any system (Cherns, 1987). One such approach is organized into three categories: meta, content, and process (Clegg, 2000). The meta category is focused on defining the “values” that drive design, the content category on identifying “what” needs to change or be accomplished, and the process category on determining “how” the first two categories can be realized (Carayon, 2006). To complement this top-down approach, the committee applied a bottom-up approach, in which committee members discussed current research to determine whether the “simple rules” presented in Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001) would be applicable to this new, 21st-century system and for health care settings globally, and agreed that this was indeed the case. By applying this methodical approach, the committee was able to formulate the following principles for designing health care delivery (see Table 2-1). These principles are intended to serve as guidelines for detailed designs, which need to emerge from and be adapted to local contexts.

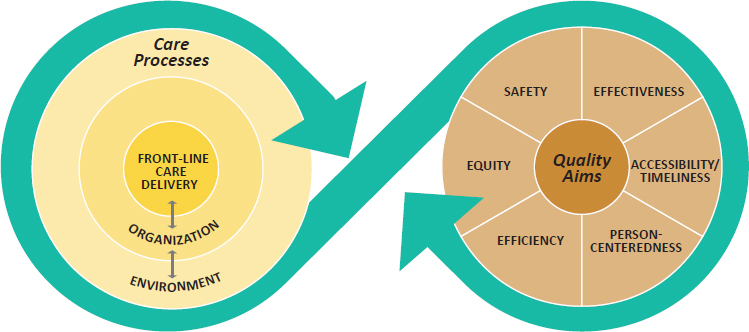

At the core of the committee’s proposed design principles is a framework that considers the various health system levels (as laid out in Chapter 1), the role of human factors, and the structure of the work system (see Figure 2-2). This framework emphasizes that health care occurs within a system in which organizational processes and environmental policies influence front-line health care delivery. Thus, an aim of implementing the above principles will be to ensure that the intersections among front-line care delivery, the organization, and the environment are self-conscious and seamless, and that system elements and care processes work well together. Only by achieving this harmonization can the quality aims of Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001) be achieved.

TABLE 2-1 Proposed New Design Principles to Guide Health Care

| Number | Principle |

|---|---|

| 1 | Systems thinking drives the transformation and continual improvement of care delivery. |

| 2 | Care delivery prioritizes the needs of patients, health care staff, and the larger community. |

| 3 | Decision making is evidence based and context specific. |

| 4 | Trade-offs in health care reflect societal values and priorities. |

| 5 | Care is integrated and coordinated across the patient journey. |

| 6 | Care makes optimal use of technologies to be anticipatory and predictive at all system levels. |

| 7 | Leadership, policy, culture, and incentives are aligned at all system levels to achieve quality aims, and to promote integrity, stewardship, and accountability. |

| 8 | Navigating the care delivery system is transparent and easy. |

| 9 | Problems are addressed at the source, and patients and health care staff are empowered to solve them. |

| 10 | Patients and health care staff co-design the transformation of care delivery and engage together in continual improvement. |

| 11 | The transformation of care delivery is driven by continuous feedback, learning, and improvement. |

| 12 | The transformation of care delivery is a multidisciplinary process with adequate resources and support. |

| 13 | The transformation of care delivery is supported by invested leaders. |

NOTE: This framework integrates Berwick’s (2002) system levels and the adapted quality dimensions of Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001) (see Chapter 1).

New Design Principles for Health Care Delivery

Meta Principles: Core Beliefs and Values

-

Systems thinking drives the transformation and continual improvement of care delivery.

Health care delivery does not always seek to achieve all six of the quality dimensions identified in Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001), often delivering on only a few of them. This gap can easily occur if a systems-thinking approach is not used to design a health system purposefully with the six quality dimensions in mind. A systems-thinking process that especially takes into consideration the interactions that take place within the work system can help address this gap.

-

Care delivery prioritizes the needs of patients, health care staff, and the larger community.

Depending on the setting, care delivery often prioritizes the needs of the health care facility over those of the patient, staff, or the community. Joint optimization among all parties is possible and should be made a continuing goal. An important component of this principle is improving health literacy among members of a community so they know what high-quality care looks like and can hold caregivers accountable. Doing so will incline patients to return to facilities, establish good relationships between facilities and the community, and give care providers a comfortable and minimally stressful work environment, thereby helping to achieve good health outcomes, continual improvement, and financial sustainability for facilities.

-

Decision making is evidence based and context specific.

As discussed in Chapter 1, the quality of care delivery in LMICs varies significantly, in part because of both a “know” gap and a “know-do” gap. Given the inconsistent use of evidence-based practices across health care facilities, there is a clear need to increase efforts to disseminate guidelines more widely and invest in supportive structures that allow for their consistent implementation and their context-specific application.

-

Trade-offs in health care reflect societal values and priorities.

Designing care delivery systems entails trade-offs—for example, between resources and outcomes or equity and efficiency. For years, however, the trade-offs made have been determined by donors, investors, or politicians or the lending requirements of development banks. As a result, trade-offs have frequently been forced on health care systems instead of being based on societal values. As countries increasingly invest their own resources in the develop-

- ment of health systems, leaders should base the trade-offs made on the values of their own communities and health facilities, taking national cultural factors into account.

Content Principles: Core Characteristics of High-Performing Care Delivery

-

Care is integrated and coordinated across the patient journey.

As discussed in Chapter 1, health care currently is fragmented and siloed, often involving multiple providers at multiple facilities who may even be in different networks and often do not share information with one another. Given this lack of communication, a patient’s vital information may be missing in subsequent encounters, and the burden is on system users as patients to update each provider with what they know. Quality outcomes are then attributed to each encounter alone rather than being recognized as the result of a continuum. Instead, the system should track the patient journey—not just over multiple encounters but ideally over a person’s life course. This would enable more seamless coordination among multiple organizations and open up a channel for dialogue between the health system and the person to capture the patient’s experience.

-

Care makes optimal use of technologies to be anticipatory and predictive at all system levels.

For a health care system to truly track information across the patient journey, it needs to be backed by robust technologies, which offer the added benefit of allowing health care to be anticipatory. Currently, health care delivery is far too episodic, reactive, and treatment-based. Using technology and leveraging the promise of algorithms, artificial intelligence, and data sciences more broadly, health care systems can provide care that is anticipatory and predictive. The increasing usage of digital health technologies globally makes this vision even more feasible. The role that technology can play in transforming health care delivery is discussed further in Chapter 3.

-

Leadership, policy, culture, and incentives are aligned at all system levels to achieve quality aims, and to promote integrity, stewardship, and accountability.

To achieve organizational goals—including, in health care facilities, the goal of high-quality care—leadership, culture, and incentives must work in concert. However, many health care facilities in low-resource settings do not align these three supportive structures as necessary. If a facility sought to achieve iterative improvements

- in quality but used punitive incentives, for example, the end goal might not be achieved because of misalignment of leadership and incentives. Aligning leadership, culture, and incentives will be essential for creating a learning health care system (discussed in Chapter 8).

-

Navigating the care delivery system is transparent and easy.

As emphasized throughout this report, the patient experience is a vital aspect of health care. Should patients have difficulty navigating the system, feel disrespected, or be unaware of their health care options, outcomes will suffer, and patients likely will not return to a facility. Thus, improving the patient experience and reducing the barriers to navigating the care delivery system will help achieve high-quality care.

-

Problems are addressed at the source, and patients and health care staff are empowered to solve them.

Health care is often viewed as simply a provider–patient encounter. However, this is a reductionist perspective. It ignores upstream inefficiencies in a hospital, and it can easily ignore the profound effects of social determinants of health. For example, the causes of a patient’s failure to adhere to a treatment may have little to do with the patient’s decisions or will, but instead may result from a stockout at a pharmacy, the need to travel long distances, or stigma. Thus, by attempting to identify the upstream causes of poor outcomes, a health care system can achieve better health outcomes. The capacity for such analysis has been realized in various existing learning health care systems and has benefited from innovative team-based health care models that include ancillary health care workers, such as those in social work and community health workers.

Process Principles: Core Processes for Transforming Care Delivery

-

Patients and health care staff co-design the transformation of care delivery and engage together in continual improvement.

The transformation of health care delivery is frequently driven by a top-down approach that fails to account adequately for the actual, felt needs of patients and providers. Given the essential role of human factors and the work system in health care outcomes, as discussed earlier, this is a misguided approach. For optimal outcomes, it is necessary for the transformation process to start and end with input and involvement from end users (both patients and providers). Such a human-centered approach is emerging in global health, being used most frequently with digital health technologies

- to maximize their impact when introduced in the field. However, before such patient input can be provided, it will be important for health systems to build health literacy among their populations. The potential for co-design, especially in the context of digital health, to contribute to the future transformation of health care is discussed in greater depth in Chapter 3.

-

The transformation of care delivery is driven by continuous feedback, learning, and improvement.

Often, the transformation of care is driven by command and control. However, this approach leaves little room for understanding the right balance among staffing, commodities, and technology, or even what care delivery models and protocols yield the best outcomes. Instead of issuing decrees, health care leaders should seek to implement a system that generates data, provides continual feedback, and creates opportunities for learning and improvement at all levels. Such a system is a first step toward creating the culture of a learning health care system. While most documented examples of the development of learning health care systems come from the United States (Finney Rutten et al., 2017; Psek et al., 2015), the emergence of this approach in Kenya (Irimu et al., 2018) indicates that this goal is feasible for low-resource settings.

-

The transformation of care delivery is a multidisciplinary process with adequate resources and support.

The transformation of care delivery usually falls under the purview of health care managers or physicians. Their skills and ability to produce valuable change notwithstanding, other important skills are necessary for care transformation as well. This is especially true as an increasing number of health care facilities turn to digital technologies to deliver care and to shift the locus of care delivery from hospitals to communities. The transformation of care thus requires a multidisciplinary process that encompasses people with backgrounds in human factors and ergonomics, anthropology, human-centered design, information and communication technology, and other sectors. While ambitious, such a model has already been launched at Hospital Italiano in Buenos Aires.2

___________________

2 Hospital Italiano in Buenos Aires, Argentina, has a portfolio of health informatics, housed in a stand-alone department that was established in 1999 within the health care network. Department personnel are from backgrounds such as sociology, anthropology, research, technology development, and engineering and include medical students to inform how digital health technologies are being used and how they can improve. The department’s operations are heavily influenced by invested leadership and governance (personal communication, C. Murga, Chief Resident, Health Informatics, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, February 20, 2018).

-

The transformation of care delivery is supported by invested leaders.

Given the multiple different perspectives involved when a multidisciplinary process is implemented, conflicts will inevitably arise. This is especially true if health care workers who previously had traditional forms of professional autonomy must relinquish control of portions of their scope of practice. Thus, the transformation of care will also require an investment from leadership that entails not only resources but also the time and commitment needed to build organizational support, keep a focus on overall aims, and negotiate conflicts.

The committee acknowledges that these proposed design principles are ambitious and disruptive to many prevailing habits and beliefs, but firmly believes they are realistic and should be used as a guide and vision for health care systems in all settings. Furthermore, the committee believes that setting future-oriented goals will be useful for health systems as they undergo transformation as a result of the emergence of digital health technologies. Applying these principles will also help health care facilities in low-resource settings avoid the some of the inefficiencies that plague their counterparts in high-income settings.

Using a Systems Approach and Applying the Committee’s Design Principles for a More Person-Centered Health System

The committee believes that by applying the above design principles, it is possible to achieve a health system that is more person-centered. The approach embodied in these principles represents a shift not only from organizing care delivery around providers and facilities, but also from the conventional notion of person-centered care to care that aims to improve the experiences of family members and providers as well.

First, by specifying a systems-thinking approach for the transformation of care delivery and calling for consideration of the needs of patients and health care staff, the design principles envision care that acknowledges a person’s self-determination and personal preferences and reflects respect for choices while also supporting health workers and providing employment conditions that are safe and promote their well-being. An indicator of whether these characteristics are being achieved is increased health literacy and effective communication among all parties. Trusted and accurate communication between health care staff and patients (and their family members) is a central clinical function and a key component of quality health care delivery (Ha and Longnecker, 2010). Effective communication has been linked not only to higher patient satisfaction, amenability

to follow-up, and adherence to care but also to improved health outcomes (Ha and Longnecker, 2010). To achieve such communication, it is essential to minimize information asymmetry between providers and patients (and their family members) so that everyone comes to the table feeling like an equal participant.

Second, care delivery can be further characterized as person-centered if it takes societal values into account. Health care by its very nature is a social endeavor as it consists of interactions among people. As care delivery becomes transformed, however, it goes beyond these interactions to reflect the values that exist locally. Only by doing so is it possible to ensure that changes made can truly support person-centered care (Sheikh et al., 2014). To this end, it is necessary to engage multiple stakeholders in decision making on how to structure service delivery and direct resources (Sheikh et al., 2014), creating a foundation on which patients and health care staff can co-design changes (Gilson, 2003) to make health care more person-centered.

Third, by seeking to make health care more integrated and coordinated and to make navigation of the care delivery system more transparent, it becomes possible to structure care in a way that optimizes interaction for those the system serves: the patients. Integration of care allows patients and their families to access multiple, related services at the same facility instead of traveling to multiple sites, while coordination of care assists patients with multiple health needs. Taken together, integration and coordination of care help organize services around the patient such that quality will be improved, while more transparent navigation of the care delivery system can reduce the burden patients experience when they access care. It is important to note that integration and coordination of services will likely be of little value unless health care facilities are open at times convenient for patients. For those without sick days or paid time off, missing work to travel to a health care facility can impose an enormous opportunity cost, making patients less likely to access care.

Finally, the committee wishes to emphasize that, although ambitious, its design principles are within reach of many health care systems in LMIC settings, and are often already being used. The examples in Box 2-2 illustrate this point.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATION

Progress in the transformation of health care will require an unprecedented commitment to quality improvement, but it will not be possible to continue using the methods and approaches of the past. The future, person-centered health system, recognized as a complex system with multiple interactions and human behaviors, will require the development and adoption of new models of care; embracement of the new forms of care

delivery; the application of the design principles set forth in this chapter; and much greater participation of patients, families, and communities in the assessment and design of care systems. The key will be an unwavering focus on what matters to patients, their families, and communities and the application of systems thinking as the scientific foundation for change, centered on an individual’s journey through the health care system. Many countries have already undertaken efforts to improve the quality of their country’s health care, using systems approaches and principles similar to those the committee is endorsing. Such efforts are possible at many levels of the health care enterprise, and should continue across a variety of settings.

Conclusion: Current health care systems cannot reliably achieve the levels of quality that patients need and have a right to expect. Their designs are inadequate to that task, and their fundamental redesign—built on what currently exists and functions—is required. Many countries have already integrated elements of person-centered care into their health care systems and can provide lessons to help guide future efforts. In the systems of the future, the needs of citizens and the patients will need to come first, shaping the demand for and the design and delivery of care. Health systems need to embrace a vision of the patient journey that is anticipatory, not reactive, and wholly centered on continually improving the experience of patients, families, and communities.

Recommendation 2-1: Fundamentally Redesign Health Care Using Systems Thinking

Health care leaders should dramatically transform the design of health care systems. This transformation should reflect modern systems thinking, applying principles of human factors and human-centered design to focus the vision of the system on patients and their experiences and on the community and its health.

To guide that new care system, health care leaders should adopt, adapt, and apply the following design principles:

- Systems thinking drives the transformation and continual improvement of care delivery.

- Care delivery prioritizes the needs of patients, health care staff, and the larger community.

- Decision making is evidence based and context specific.

- Trade-offs in health care reflect societal values and priorities.

- Care is integrated and coordinated across the patient journey.

- Care makes optimal use of technology to be anticipatory and predictive at all system levels.

- Leadership, policy, culture, and incentives are aligned at all system levels to achieve quality aims, and to promote integrity, stewardship, and accountability.

- Navigating the care delivery system is transparent and easy.

- Problems are addressed at the source, and patients and health care staff are empowered to solve them.

- Patients and health care staff co-design the transformation of care delivery and engage together in continual improvement.

- The transformation of care delivery is driven by continuous feedback, learning, and improvement.

- The transformation of care delivery is a multidisciplinary process with adequate resources and support.

- The transformation of care delivery is supported by invested leaders.

REFERENCES

Adu-Krow, W., V. Mahadeo, V. E. Bachan, and M. Ramdeen. 2018. Guyana: Holistic geriatric mega-clinics for care of the elderly in Guyana. In Health systems improvement across the globe: Success stories from 60 countries, edited by J. Braithwaite, R. Mannion, Y. Matsuyama, P. Shekelle, S. Whittaker, and S. Al-Adawi. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Pp. 41–47.

Armitage, G. D., E. Suter, N. D. Oelke, and C. E. Adair. 2009. Health systems integration: State of the evidence. International Journal of Integrated Care 9:e82.

Bagian, J. P. 2012. Health care and patient safety: The failure of traditional approaches—how human factors and ergonomics can and must help. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries 22(1):1–6.

Bazzano, A. N., J. Martin, E. Hicks, M. Faughnan, and L. Murphy. 2017. Human-centred design in global health: A scoping review of applications and contexts. PLoS One 12(11):e0186744.

Berwick, D. M. 2002. A user’s manual for the IOM’s “quality chasm” report. Health Affairs 21(3):80–90.

Bodenheimer, T., and C. Sinsky. 2014. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. The Annals of Family Medicine 12(6):573–576.

Braithwaite, J., W. B. Runciman, and A. F. Merry. 2009. Towards safer, better healthcare: Harnessing the natural properties of complex sociotechnical systems. Quality and Safety in Health Care 18(1):37. doi:10.1136/qshc.2007.023317.

Buckle, P., S. Walne, S. Borsci, and J. Anderson. 2018. Human factors and design in future health care. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Global/GlobalQualityofCare/Meeting%203/Buckle%20presentationHuman%20Factors.pdf (accessed March 15, 2018).

Carayon, P. 2006. Human factors of complex sociotechnical systems. Applied Ergonomics 37(4):525–535.

Carayon, P., A. Schoofs Hundt, B. T. Karsh, A. P. Gurses, C. J. Alvarado, M. Smith, and P. Flatley Brennan. 2006. Work system design for patient safety: The SEIPS model. Quality and Safety in Health Care 15(Suppl. 1):i50.

Carayon, P., E. Bass, T. Bellandi, A. Gurses, S. Hallbeck, and V. Mollo. 2011. Socio-technical systems analysis in health care: A research agenda. IIE Transactions on Healthcare Systems Engineering 1(1):145–160.

Center for Health Market Innovations. 2018. PurpleSource Healthcare. https://healthmarketinnovations.org/program/purplesource-healthcare (accessed May 20, 2018).

Cherns, A. 1987. Principles of sociotechnical design revisted. Human Relations 40(3):153–161.

Chisholm, R. F., and J. T. Ziegenfuss. 1986. A review of applications of the sociotechnical systems approach to health care organizations. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 22(3):315–326.

Clegg, C. W. 2000. Sociotechnical principles for system design. Applied Ergonomics 31(5):463–477.

Cook, R. I., and D. D. Woods. 1994. Operating at the sharp end: The complexity of human error. In Human error in medicine, edited by M. S. Bogner. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Pp. 255–310.

Donabedian, A. 1988. The quality of care: How can it be assessed? Journal of the American Medical Association 260(12):1743–1748.

Drues, M. 2014. Combination products 101: A primer for medical device makers. Med Device Online, March 25. https://www.meddeviceonline.com/doc/combination-products-a-primer-for-medical-device-makers-0001 (accessed July 18, 2018).

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2016a. Applying human factors and usability engineering to medical devices: Guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff. Silver Spring, MD: FDA.

FDA. 2016b. Human factors studies and related clinical study considerations in combination product design and development: Draft guidance for industry and FDA staff. Silver Spring, MD: FDA.

Finney Rutten, L. J., A. Alexander, P. J. Embi, G. Flores, C. Friedman, I. V. Haller, P. Haug, D. Jensen, S. Khosla, G. Runger, et al. 2017. Patient-centered network of learning health systems: Developing a resource for clinical translational research. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 1(1):40–44.

Gilson, L. 2003. Trust and the development of health care as a social institution. Social Science & Medicine 56(7):1453–1468.

Gonseth, J., and M. C. Acuna. 2018. Ecuador: Improving hospital management as part of health reform process in Ecuador: The case of Abel Gilbert Pontón Hospital. In Health systems improvement across the globe: Success stories from 60 countries, edited by J. Braithwaite, R. Mannion, Y. Matsuyama, P. Shekelle, S. Whittaker, and S. Al-Adawi. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Pp. 33–39.

Ha, J., and N. Longnecker. 2010. Doctor–patient communication: A review. The Oschner Journal 10(1):38–43.

HFG (Health Finance and Governance) Project. 2017. Engaging non-state actors in governing health—the key to improving quality? https://www.slideshare.net/HFGProject/engaging-nonstate-actors-in-governing-health-key-to-improving-quality-of-care (accessed July 10, 2018).

Hodsden, S. 2016. FDA clarifies human factor studies for medical device and combination product design. https://www.meddeviceonline.com/doc/fda-clarifies-human-factor-studies-for-medical-device-and-combination-product-design-0001 (accessed July 15, 2018).

Hollnagel, E., R. L. Wears, and J. Braithwaite. 2015. From Safety-I to Safety-II: A white paper. Denmark, UK: University of Southern Denmark; Gainesville, FL: University of Florida; and Sydney, Australia: Macquarie University. https://www.england.nhs.uk/signuptosafety/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2015/10/safety-1-safety-2-whte-papr.pdf (accessed August 10, 2018).

IEA (International Ergonomics Association). 2018. Definition and domains of ergonomics. https://iea.cc/whats/index.html (accessed May 17, 2018).

Innovations in Healthcare. 2018. PurpleSource. https://www.innovationsinhealthcare.org/profile/purplesource (accessed May 20, 2018).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2001. Crossing the quality chasm. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Irimu, G., M. Ogero, G. Mbevi, A. Agweyu, S. Akech, T. Julius, R. Nyamai, D. Githang’a, P. Ayieko, and M. English. 2018. Approaching quality improvement at scale: A learning health system approach in Kenya. Archives of Disease in Childhood. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2017-314348.

Kaplan, G., G. Bo-Linn, P. Carayon, P. Provonost, W. Rouse, P. Reid, and R. Saunders. 2013. Bringing a systems approach to health. http://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/SAHIC-Overview.pdf (accessed May 17, 2018).

Lawler, E. K., A. Hedge, and S. Pavlovic-Veselinovic. 2011. Cognitive ergonomics, sociotechnical systems, and the impact of healthcare information technologies. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 41(4):336–344.

Mao, X., P. Jia, L. Zhang, P. Zhao, Y. Chen, and M. Zhang. 2015. An evaluation of the effects of human factors and ergonomics on health care and patient safety practices: A systematic review. PLoS One 10(6):e0129948.

Mason, A., M. K. Goddard, and H. L. A. Weatherly. 2014 (unpublished). Financial mechanisms for integrating funds for health and social care: An evidence review. CHE Research Papers, No. 97. York, UK: University of York, Centre for Health Economics.

Mounier-Jack, S., S. H. Mayhew, and N. Mays. 2017. Integrated care: Learning between high-income, and low- and middle-income country health systems. Health Policy and Planning 32(Suppl. 4):iv6–iv12.

Nigenda-Lopez, G. H., C. Juarez-Ramirez, J. A. Ruiz-Larios, and C. M. Herrera. 2013. Social participation and quality of health care: The experience of citizens’ health representatives in Mexico. Revista de Saúde Pública 47(1):44–51.

NRC (National Research Council). 2011. Health care comes home: The human factors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nyirandagijimana, B., J. K. Edwards, E. Venables, E. Ali, C. Rusangwa, H. Mukasakindi, R. Borg, M. Fabien, M. Tharcisse, A. Nshimyiryo, et al. 2017. Closing the gap: Decentralising mental health care to primary care centres in one rural district of Rwanda. Public Health Action 7(3):231–236.

PharmAccess Foundation. 2016. PharmAccess partners with PurpleSource Healthcare in Nigeria. https://www.pharmaccess.org/update/pharmaccess-partners-with-purplesource-healthcare-in-nigeria (accessed May 20, 2018).

Psek, W. A., R. A. Stametz, L. D. Bailey-Davis, D. Davis, J. Darer, W. A. Faucett, D. L. Henninger, D. C. Sellers, and G. Gerrity. 2015. Operationalizing the learning health care system in an integrated delivery system. EGEMS (Washington, DC) 3(1):1122. doi:1110.13063/12327-19214.11122.

Ruelas, E. 2002. Health care quality improvement in Mexico: Challenges, opportunities, and progress. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center) 15(3):319–322.

Rusangwa, C. 2017. Integrating mental health into primary care: Expanding a community-based Mentorship and Enhanced Supervision (MESH) model to address severe mental disorders in Rwanda. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Global/GlobalQualityofCare/Meeting%202/Presentations/Rusangwa%20Partners%20in%20Health.pdf (accessed April 15, 2018).

Searl, M. M., L. Borgi, and Z. Chemali. 2010. It is time to talk about people: A human-centered healthcare system. Health Resarch Policy and Systems 8(35). doi:10.1186/1478-4505-1188-1135.

Sheikh, K., M. K. Ranson, and L. Gilson. 2014. Explorations on people centredness in health systems. Health Policy and Planning 29(Suppl. 2):ii1–ii5.

The Economist. 2018. Hospitals are learning from industry how to cut medical errors. https://www.economist.com/international/2018/06/28/hospitals-are-learning-from-industry-how-to-cut-medical-errors (accessed July 8, 2018).

Vaughan, D., M. Guerrero, Y. K. A. Maslamani, and C. Pain. 2018. Qatar: Successful implementation of a deteriorating patient safety net system: The Qatar Early Warning System. In Health systems improvement across the globe: Success stories from 60 countries, edited by J. Braithwaite, R. Mannion, Y. Matsuyama, P. Shekelle, S. Whittaker, and S. Al-Adawi. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Vicente, K. J. 2003. What does it take? A case study of radical change toward patient safety. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 29(11):598–609.

Vicente, K. J., K. Kada-Bekhaled, G. Hillel, A. Cassano, and B. A. Orser. 2003. Programming errors contribute to death from patient-controlled analgesia: Case report and estimate of probability. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia 50(4):328–332.

Vincent, C., and R. Amalberti. 2016. Safer healthcare: Strategies for the real world. New York: Springer International Publishing.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2009. Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. Geneva, Switzerland: Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO.

WHO. 2010. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: A handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

WHO. 2015. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: Interim report. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

Zhang, J., T. R. Johnson, V. L. Patel, D. L. Paige, and T. Kubose. 2003. Using usability heuristics to evaluate patient safety of medical devices. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 36(1):23–30.