4

Exploring Opportunities in Correctional Health, Law, and Law Enforcement

This chapter summarizes presentations and discussions about opportunities for treatment and prevention in correction health, law, and law enforcement. Josiah “Jody” Rich, professor of medicine and epidemiology at the Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown University, described the interplay between correctional health and the opioid epidemic. Leo Beletsky of Northeastern University’s School of Law and Bouvé College of Health Sciences and the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine explored the use of law as a tool for addressing addiction and its consequences. Captain Katie Goodwin of the Anne Arundel County Police Department, Maryland, provided a law-enforcement perspective on the opioid epidemic.

CORRECTIONAL HEALTH AND THE OPIOID EPIDEMIC

Jody Rich focused on the opioid epidemic in correctional health settings, drawing on two decades spent working in prison health care. In the midst of an epidemic of incarceration, he observed, the United States also has an epidemic of opioid use disorder. The natural history of opioid use disorder often leads to involvement with the criminal justice system, he added, and the system has the potential to play an important role in reducing the opioid epidemic and its infectious disease consequences. Despite a glut of resources being poured into the criminal justice system supposedly aimed at dealing with addiction, he stated that punishment does not work against addiction. He cautioned that resources are being

squandered by filling jails and prisons, which is exacerbating the opioid epidemic in correctional facilities rather than mitigating it. He observed that prisoners, minorities, poor people, and people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are all very stigmatized populations, but people with addiction are the most stigmatized of all: the perception that they are the “lowest of the low, the subhuman” pervades the culture. While the focus on eliminating the opioid epidemic and associated infections is critical, he said, it should also be used as an opportunity to examine the stigma around people with this disease, the people that provide care, and the programs that provide care.

Epidemic of Incarceration

Concerns about increasing rates of incarceration in the United States first came to the fore in the early 1980s, explained Rich, and subsequent years saw the U.S. state and federal prison populations explode from around 400,000 people in 1982 to almost 1.5 million people in 2015. The racial disparities in prisons across the country are striking, he added. The lifetime likelihood of imprisonment is 1 in 9 for all men, but the likelihoods are 1 in 3 for black men, 1 in 6 for Latino men, and just 1 in 17 for white men (Bonczar, 2003). The disparities in likelihood of imprisonment among white women (1/111) versus black women (1/18) and Latina women (1/45) are less extreme but still striking, he added. More than half of people in U.S. prisons have a diagnosis, or dual diagnosis, of drug dependence, alcohol dependence, and/or serious mental illness; the rate of opioid use disorder hovers around 15 percent (Baillargeon et al., 2009; James and Glaze, 2006; Peters et al., 1998).

There are substantial overlaps between infectious diseases and incarceration and between incarceration and addiction, Rich said. Prisons and jails across the country have a huge amount of turnover, with around 10 million people coming in and out of incarceration each year. A study on the percent of the total burden of infectious disease passing through correctional facilities in 1997 found that between 20–26 percent of people with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) cycled through prisons and jails that year, as did 12–16 percent of people with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV), 29–32 percent of people with hepatitis C virus (HCV), and around 38 percent of people with tuberculosis (Hammett et al., 2002). The dramatic drop in age-related deaths countrywide in the mid-1990s due to effective antiretroviral therapies was mirrored in correctional settings, Rich said, which indicated that some people were receiving treatment inside.

However, very little is known about health care provided in correctional settings owing to lack of accountability (other than through litiga-

tion), lack of standardization, and lack of evaluation of the care and treatment prisoners receive. A retrospective cohort study followed more than 2,000 HIV-infected inmates who were discharged from the Texas prison system with 10 days of antiretroviral medication. They were required to refill the prescription within 5 days to continue their therapy, and only 5 percent filled the prescription within 10 days, and only 30 percent had done so within 60 days (Baillargeon et al., 2009). Therefore, 95 percent of people on HIV treatment interrupted their therapy upon their release and were thus more likely to transmit the infection at a time when they were likely to reengage or newly engage in sexual relationships and/or relapse to drug use. Even though care is provided inside the prisons and outside the prisons, he added, the transition out of prison is a critical point at which care is interrupted.

Opioid Epidemic

Turning to the opioid epidemic, Rich emphasized that drug overdoses are now the leading cause of death for Americans under the age of 50. He reported that up to 65,000 people are estimated to have died from overdose in the United States in 2016 alone, surpassing the peaks for gun violence deaths (just under 40,000 in 1993); HIV deaths (more than 45,000 in 1995); and car crash deaths (just under 55,000 in 1972). The proliferation of fentanyl is further promulgating the epidemic in all corners of the country, said Rich, as are the high rates of incarceration and social determinants of health such as poverty, income inequality, poor education, lack of health insurance, lack of health care, and lack of Medicaid expansion. Rich explained that addiction is a primary, chronic brain disease that is poorly understood, but has defining characteristics of compulsive drug seeking, continued use despite the adverse and harmful consequences, and cycles of recurrence and remission.

Three types of factors contribute to the development of opioid use disorder. The first, genetics, is likely the most powerful. The second are situational characteristics, such as peer pressure and experiences of trauma and/or abuse both before and after opioid use—the latter is almost universal among women but also common in men, he added. The third component is exposure, because people cannot develop opioid use disorder if opiates are not available; on the contrary, the market is now flooded with millions of prescription opiates. A person who uses prescription opiates is then at risk of transitioning to cheaper heroin, and then starting to inject it because of increased tolerance.

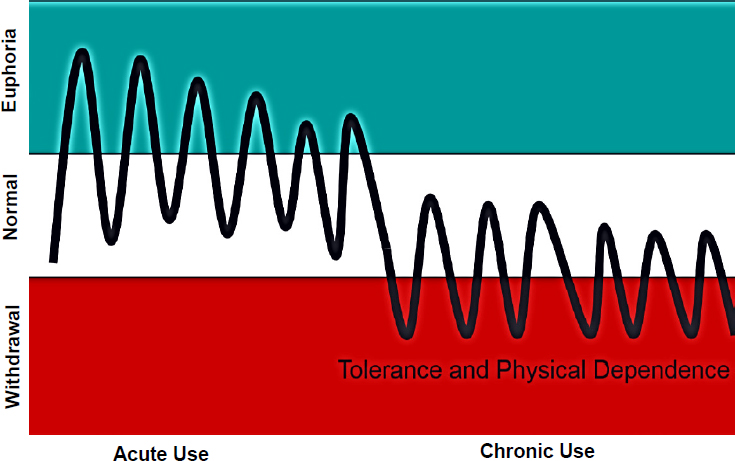

Rich explained that opiates have two fundamental characteristics—tolerance and withdrawal—both of which can occur within days or weeks of first using an opiate. Figure 4-1 provides a visual representation of how

SOURCES: As presented by Jody Rich at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 12, 2018; adapted from Dole et al., 1966.

tolerance and physical dependence on opioids can develop. Increased tolerance necessitates increasingly higher doses to get the same euphoric effect. Rich likened the withdrawal phenomena to feeling like you are going to die. This causes people to resort to desperate measures to obtain more drugs and stop the withdrawal. Over time, people may not even experience the feeling of euphoria anymore—they just want to feel normal by using to get out of withdrawal. He added that incarcerated patients who have not used opiates in years can experience physiologic withdrawal symptoms just from talking about using opiates, despite the drugs having had such disastrous consequences in their lives.

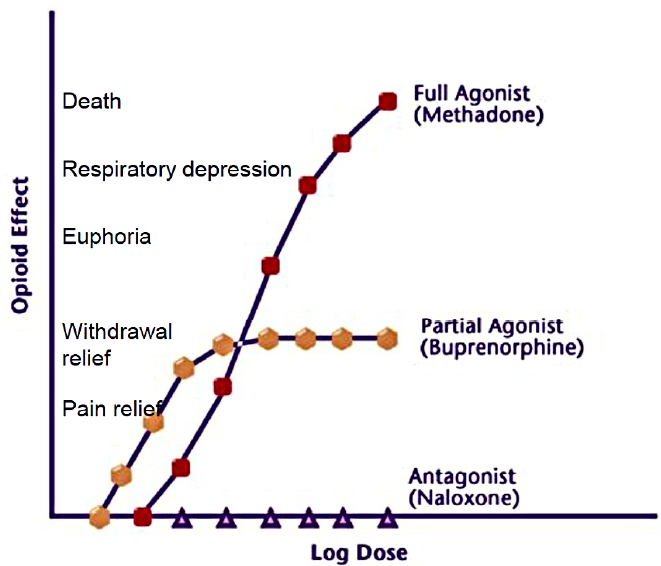

“When you think about all of the challenges of transitioning from being incarcerated to being back in the community . . . it is a wonder that anybody is able to make that transition without relapsing,” Rich said. However, medications for addiction treatment can and do save lives. Baltimore ramped up opioid agonist therapy (OAT) and drove down overdose deaths by almost 80 percent by 2009. Three very effective medications are available that work through different mechanisms to block a patient from getting high and keeping the patient out of withdrawal (see Figure 4-2). Despite clear science that medications for addiction treatment

SOURCES: As presented by Jody Rich at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 12, 2018; CSAT, 2004.

are effective, people often face stigma that they are not actually “clean” if they are on medication. This type of attitude—which may be espoused by the patient’s family, policy makers, and even clinicians—leads to higher risks of relapse and overdose, he warned, and detoxification itself is not a treatment that helps people stay off drugs (Ling, 2016).

Rapid Access to Treatment in Correctional Facilities

Rich described his experience as part of the Rhode Island Governor’s Taskforce on Overdose Prevention. An estimated 20,000 of Rhode Island’s population of 1 million people have opioid use disorder, so the taskforce decided to provide medications for addiction treatment in every possible setting—emergency departments, hospitals, mental health clinics, and addiction treatment clinics. He noted that when emergency departments start patients on MAT, the rate of treatment success 1 month later is doubled. The taskforce also decided to provide MAT throughout the

entire correctional system, including prisons, jails, courts, law enforcement, probation services, and parole services. Previously, people in correctional facilities had been treated for opioid use disorder during their incarceration and then released without continuity of care. “When you take them off their illicit opiates, their tolerance goes down. You let them out and they are set up for fatal overdose,” he explained. The state budgeted $2 million to establish a MAT program in the Rhode Island Department of Corrections that would screen everyone entering the system for opioid use disorder, offer the best possible treatment for each individual, and then link patients to treatment when they are released. The program began in the summer of 2016.

A recently published study compared data on mortality caused by opioid overdose in the general population to individuals with an incarceration in the 12 months prior to their death in Rhode Island during the periods of January–June 2016 (prior to the start of the program) and January–June 2017 (Green et al., 2018). The study found a 12 percent decrease in overdose mortality statewide, at a time when mortality curves elsewhere in the country were continuing to climb. Among people who had been released from incarceration within the previous 12 months, there was a 65 percent absolute decrease, representing a relative risk reduction of 61 percent in overdose mortality by connecting people with medications for addiction treatment in incarceration within 1 year of starting the program. He argued that based on these results, providing MAT in correctional facilities is clearly the right direction. However, he cautioned that MAT programs outside of the correctional system need to be ramped up because “There is almost no point in starting a treatment program behind bars if you don’t have someplace to connect people to.”

Discussion

Sandy Springer, associate professor at the Yale School of Medicine, wondered how expanding MAT for populations coming out of prisons and jails would affect the HIV and HCV epidemic, both for those who are living with HIV and with respect to improving the HIV continuum of care. Rich contended that the preliminary results of the intervention in Rhode Island indicate that it has great potential to mitigate the epidemic. He noted that the initial report only looks at overdose deaths, which is only the tip of the impact’s iceberg, which also includes improvements in HCV and HIV care. A workshop participant asked how the Rhode Island correctional system was convinced to provide agonist therapy, because more correctional systems tend to prefer antagonist therapy. Rich explained that all three types of medications were available to patients. Of the first 1,000 patients, approximately half ended up on methadone

and half on buprenorphine; only about a dozen patients opted for depot naltrexone. He emphasized that 99 percent of correctional facilities across the country offer nothing and the ones that do offer treatment primarily offer an extended-release naltrexone program without follow-up.

Evidence suggests that the drug is effective, but a 60 percent reduction will not be achieved if only one medication is offered—the medication offered should be tailored to the specific person’s symptoms and biological response, said Rich. To convince correctional authorities, the taskforce emphasized that providing the medication in a public institution (i.e., a correctional facility) is a public health intervention to address a nationwide public health epidemic. He acknowledged that diversion is a real problem that warrants security enhancements, given the abuse potential of methadone among people who are addicted to drugs. However, Rich argued that correctional facilities should not be permitted to make such decisions about which medications they provide. “This is a public health epidemic,” he said. “We can’t just let those 60 percent of people drop dead after they walk out of our facility because we don’t believe in these agonist therapies. . . . That is absolutely unacceptable. That is morally wrong.”

USING LAW TO ADDRESS ADDICTION AND ITS CONSEQUENCES

In his presentation, Leo Beletsky explored how law can be used as a tool to address infectious diseases and other negative health consequences of opioid use and misuse. Law and its enforcement are structural determinants of drug user health that have shaped the current opioid crisis faced today. Law can also help shape how infectious disease prevention research is translated into policy and how that policy is implemented on the ground, he explained. Law has both led and followed innovation in the realm of addiction and infectious disease, with current best practices evolving out of acts of civil disobedience. Policy change has been a bottom-up process in the broader field of infectious disease prevention as it applies to substance use in the United States. It often begins with local experimentation and percolates upward to state-level adoption of interventions such as syringe exchanges, pharmacy reforms, and—potentially—safe consumption facilities. Policy tools and legal mechanisms are critical as enablers of effective implementation of these sorts of innovations, he said.

Beletsky sketched out a conceptual framework to explain how laws can have direct, indirect, and normative effects on the health of people who use drugs (PWUD). In terms of the direct effect, drug laws shape access to syringes and condoms; public health prevention efforts like syringe exchange programs (SEPs) and OAT require a legal basis

(Blankenship and Koester, 2002; Davis et al., 2017; Green et al., 2012, 2018). Indirectly, drug laws shape drug user behaviors such as rushed injections, syringe sharing, and overdose while incarceration drives disease transmission, substance use, and fatal reentry (Beletsky et al., 2013, 2015b). Normatively, laws can shape societal views and norms around certain risky behaviors, given that the very role of criminal law is to codify and project stigma. Marginalization further impedes public health efforts and is an entry point to isolation, discrimination in health care, criminal justice involvement, and so forth, Beletsky continued. On the positive side, law can also enable risk reduction through structural interventions to change the environmental conditions that shape health. The evolving field of public health law and public health law research focuses on designing and deploying laws as structural interventions with methodological rigor to improve public health (Beletsky et al., 2012; Burris et al., 2010). Legal interventions that have been advanced and propagated to reduce infectious disease risk include

- decriminalization of syringe and drug possession;

- authorization of syringe exchange, pharmacy sales, and OAT;

- antidiscrimination laws;

- access to health care, health insurance, housing, and wraparound services; and

- due process and other procedural protections.

More structural-level legal interventions can also create an enabling environment to understand whether interventions are working in practice, said Beletsky. A caveat to legal interventions rooted in implementation science is how interventions translate to the ground level. Laws “on the books” are shaped to improve the risk environment for PWUD. However, their fidelity on the ground will not necessarily be perfect or even reflective of that objective, because laws “on the streets” shape how formal laws are implemented at the street level (Burris et al., 2004). This tension, he said, creates an imperative among people who use empirical tools to understand the policy transformation process to work on aligning street-level communication with the theory of structural interventions.

Beletsky drew a parallel between medical remedies and laws as structural interventions, by modeling society as the patient and law as the remedy. Within the clinical science realm, remedies must first be tested to understand the range of responses they can elicit in different individuals. This diversity makes it challenging to tailor an intervention to a specific individual. Like drugs, legal interventions have something like a “therapeutic window” within which the intended effect will be produced in different jurisdictions. Below the window’s threshold, an intervention may

produce no effect; above the threshold, it can have a toxic effect that calls for adjusting the intervention.

Beletsky explained that the trajectory of the opioid crisis has been substantially shaped by policy interventions throughout its evolution, from overdoses involving prescription drugs (the first phase) to overdoses involving heroin (the second phase). The current third phase is defined by a stratospheric increase in fentanyl-related overdoses, although both heroin and prescription opioids continue to be important factors. Modal policy interventions have included

- prescribing limits and guidelines;

- prescription drug monitoring programs;

- pill-mill laws and trafficking enforcement;

- prosecution of unscrupulous prescribers and dealers;

- reformulation and withdrawal of prescription drugs; and

- harm reduction interventions including Good Samaritan laws, naloxone access, and syringe exchanges.

Beletsky suggested that the prevailing focus on addressing the supply of opioids has come at the expense of addressing the underlying structural issues at play in shaping the crisis (Dasgupta et al., 2018). Legal and policy interventions have been major drivers of the large numbers of people who have transitioned to injection drug use, along with a variety of additional push and pull factors. Policy interventions, such as changes in the prescription drug supply, have shaped a range of negative collateral consequences in terms of infectious disease risk (Broz et al., 2018).

Although research has demonstrated policy responses that are helpful in addressing injection-related infectious disease risk, said Beletsky, that research has not been translated into policy. For example, syringe exchange is one of the best-studied and well-proven interventions, but it has been legally authorized by only 20 states as of 2018. In fact, 29 states continue to criminalize syringe possession despite evidence showing that criminal law does not deter people from engaging in drug injection (Burris, 2017). Only 11 of those states have legal exemptions for syringe possession related to public health activities, including syringe exchanges.

OAT is also well studied and proven to prevent disease transmission, he added, but the dismal access to OAT across the country has various legal drivers. In 16 states, methadone is not covered by Medicaid, one of the principal payors (amfAR, 2017). The 21st Century Cures Act (2016) created a funding push from the federal level to support MAT, infectious disease prevention, and recovery support. However, the law was framed at the agency level such that it did not specifically maintain that the money had to be used for MAT or OAT. As a result, preliminary data

suggest that some states are using funds for MAT and others are using the funds for treatment options that are not evidence based (Beletsky, in press; MDPH, 2017). Progress has been made, he said, but much work remains in translating effective policy interventions into an enabling policy environment for infectious disease prevention. Many states still lack optimal, evidence-based laws and those that have been established are fragile and may be repealed. He urged researchers to play a stronger role in actively educating and advocating for evidence-based policy.

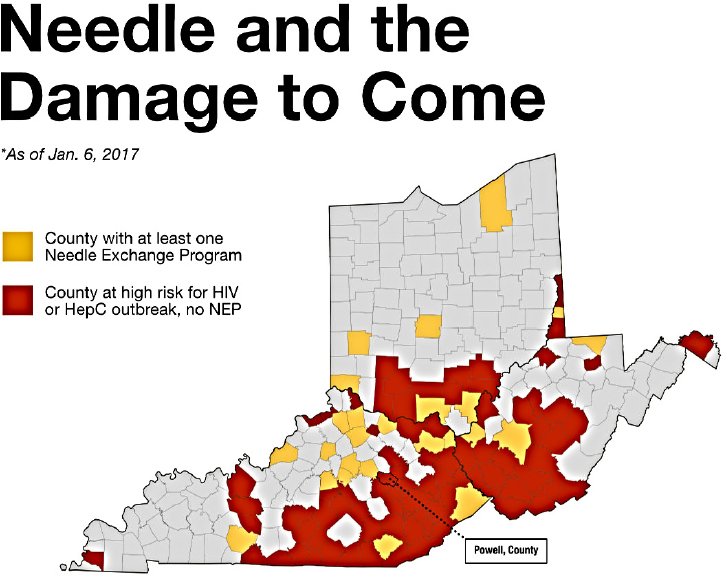

Implementing Policy on the Street Level

Beletsky shifted to the implementation of laws on the street level, which is lacking even in states that do have evidence-based policy. For example, Kentucky has authorized syringe exchange, but still had very poor coverage in dozens of counties at high risk for HIV and HCV outbreaks as of January 2017 (see Figure 4-3). He noted that Massachusetts has all the recommended policy elements in place, but still has very poor rates of OAT adherence and access. According to data from the state’s department of health, only around 5 percent of people who had a nonfatal, opioid-related overdose had engaged in OAT treatment in the subsequent year (during 2013–2014) (MDPH, 2017).

Harm Reduction, Law, and Law Enforcement

Beletsky provided an empirical perspective on the role of law-enforcement interventions. Although law enforcement play a critical role in the process of implementing laws on the ground, they can also aggravate the risk of infectious disease (Beletsky et al., 2011a,b,c; Blankenship and Koester, 2002; Burris et al., 2004; Davis et al., 2005; Kerr et al., 2005). Encounters with police such as arrest, syringe, or condom confiscation are associated with risk behavior and increased levels of infectious disease. While police interference with public health programs reduces their effect and can fuel epidemics, police can (and do) facilitate harm reduction by providing security and referring clients to services, for example. Aligning policing with public health warrants a multipronged approach that comprises law reform, changes in institutional policies and guidelines, police training, collaboration structures to bridge sectors, changing incentives, and surveillance and monitoring (Beletsky et al., 2005, 2012; Silverman et al., 2012). To illustrate, he described case studies from Baltimore, Maryland, and Tijuana, Mexico.

The Baltimore project sought to track police encounters around SEPs to understand the structural role of police in shaping access to syringe services (Beletsky et al., 2015a). Registered clients in the SEP are protected

NOTES: SEP coverage data from Kentucky sourced from CDC, the Kentucky Department of Public Health, the Center for Community Solutions, and the North American Syringe Exchange Network.

HepC = hepatitis C; NEP = needle exchange program.

SOURCES: As presented by Leo Beletsky at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 13, 2018; Meehan and Kanik, 2017.

by state law in Baltimore City, and the police department policy specifically protects SEPs and their clients. However, police encounters that were theoretically prohibited by the policy (e.g., syringe confiscation and other harassments) were still commonplace. To address this, they developed a program of annual in-service training for police covering occupational safety, drug policy, and the rationale for public health programming.

An ongoing intervention study in Tijuana, Mexico, seeks to transform the role of law enforcement from acting as a structural barrier to facilitating access and contributing to an enabling environment for prevention (Strathdee et al., 2015). In partnership with the local police academy, the

intervention is training police officers using a framework focused on the police’s intrinsic motivation, such as concerns about occupational safety (e.g., needle sticks) and frustrations around the lack of appropriate tools for working with people who inject drugs (PWID) and other vulnerable populations (Beletsky et al., 2005, 2013; Cepeda et al., 2017). After 3 months, attitudes and knowledge among police had shifted significantly and were more in line with public health goals regarding SEPs, OAT, and referrals to health and social services (Arredondo et al., 2017). Police behaviors had also changed, with decreases in the frequencies of confiscated syringes (of almost 7 percent), in arrests for heroin possession (of more than 11 percent), and an increase in the frequency of drug users referred to services (more than 8 percent). The intervention is promising in terms of cost-effectiveness, Beletsky said, but additional interventions are needed to motivate more of the officers.

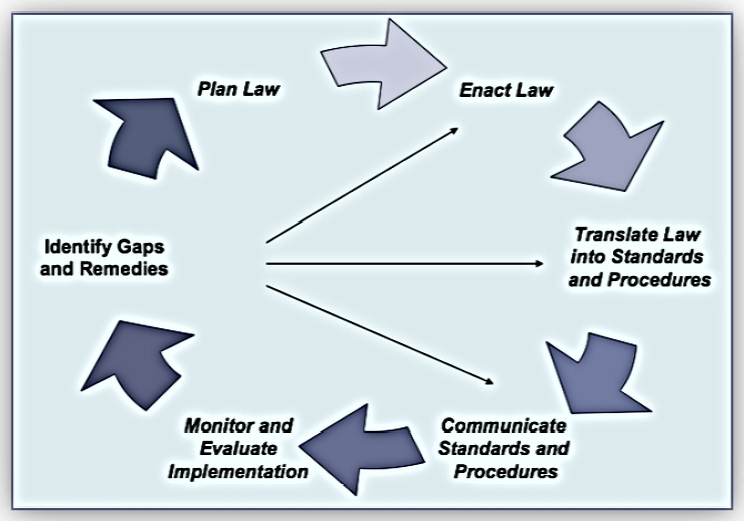

The framework of implementation science is cyclical, said Beletsky. It requires translating evidence-based policies to the street level, coupled with monitoring and evaluation to tailor and adjust laws as necessary based on empirical evidence (see Figure 4-4). Laws can both enable and

SOURCE: As presented by Leo Beletsky at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 13, 2018.

hamper infectious disease prevention in the context of current crises, thus effective translation and implementation are both critical in achieving public health goals. He concluded with a warning that in several jurisdictions where the policy environment has improved, major efforts are under way to reverse the progress. For example, Indiana has seen two of its five SEPs closed within 1 year and a similar situation is evolving in West Virginia, where opponents are calling for closing established SEPs and recriminalizing syringes. “This puts the onus on us to assist those who are trying to work towards more evidence-based policy environments,” he maintained.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT AND FIRST RESPONDERS

Like many communities across the country, Anne Arundel County in Maryland has faced rising numbers of overdoses and fatalities related to opioid use since around 2014. The police department soon realized that they would not be able to “arrest their way out of the problem,” said Katie Goodwin. She explained that the police department is working to tackle the opioid epidemic by shifting their paradigm to a three-pronged approach encompassing law enforcement, treatment for people who use drugs, and education about the opioids. Strong partnerships with the health department and the state attorney’s office serve as the foundation for the approach, she added.

Law Enforcement and Prosecution of Dealers

The law enforcement prong is centered on the prosecution of dealers who supply and deal opioids, said Goodwin. She emphasized that they are not targeting people who use opioids with criminal charges, such as when they respond to a house where someone has overdosed. Rather, they view people who use opioids as victims that need support and treatment.

Good Samaritan Law

Goodwin described how the department has been working to increase the community’s awareness of the county’s Good Samaritan law, which protects people from being arrested or criminally charged if they call emergency services to help someone who has overdosed and needs medical care. The law was put in place because people were reluctant to call 911 due to fear of being arrested if the overdose occurred in a setting where drugs and paraphernalia were present, for example. “Our whole

goal is to get us there on the scene, so we can help that individual, so they don’t die,” she said. “Saving lives is outweighing us locking up these [people who call 911], which we know isn’t going to do any good for them or for the system.” She reported that the law has encouraged more people to call emergency services in a range of settings where they would otherwise have been reluctant to call, such as parking lots, convenience store bathrooms, or residences.

Heroin Taskforce and Fatal Overdose Unit

To strengthen the law enforcement approach to addressing the increasing numbers of opioid-related overdoses and fatalities, the Anne Arundel County Police Department created a heroin taskforce and a fatal overdose unit. Goodwin reported that the county had more than 150 opioid-related fatalities in 2017 and 35 fatalities as of March 2018, which exceeds the 21 fatalities that had occurred by the same point in 2017. The heroin taskforce is a dedicated team that primarily investigates dealers who are bringing narcotics into the county and particularly dealers who sell opioids linked to overdoses. The interagency taskforce comprises seven members including three Anne Arundel County narcotics detectives, state police officers, and officers from neighboring jurisdictions of Annapolis City and Baltimore City. Thus far, several major dealers have been prosecuted, some of whom had brought drugs into Anne Arundel County from as far away as California, New York, and Texas.

The fatal overdose unit, created in the summer of 2017, includes a sergeant and four detectives who are only responsible for dealing with victims of fatal overdoses. If toxicology analysis indicates that the person who died tested positive for opioids, the unit is responsible for investigating the death as if it were a homicide. She said that 35 people are under investigation by the unit and three people have been charged with manslaughter thus far. The first person charged with manslaughter will go on trial in 2018 and will serve as a litmus test for how future trials are likely to unfold. She noted that a manslaughter charge actually carries a lighter jail sentence that a charge of opioid distribution, so they are working to change the law and make manslaughter a stiffer charge so that it serves as a greater deterrent for dealers.

Treatment of People Who Use Drugs

The second prong of the police department’s approach is focused on treating PWUD. All officers on patrol carry naloxone as part of their issued equipment, so that they can quickly administer it as first responders on the scene of an overdose. Goodwin reported that naloxone needs

to be administered by one of their officers on a daily basis in the county. Each officer now carries two vials of naloxone with them, for two reasons. First, it often takes multiple doses of the drug to revive people who have overdosed—in one case, it took seven doses to save the person’s life. The second vial is also carried to protect officers’ safety if they are exposed to opiates when responding to a scene, especially given the escalating influx of fentanyl in the drug supply (see Box 4-1).

Mobile Crisis Unit

The police department has a robust partnership with the department of health, meeting regularly and sharing information weekly. Overdose information is used to map overdoses and fatalities and monitor trends to investigate spikes in certain areas. Goodwin said that a key component of the partnership was the creation of a mobile crisis unit staffed by trained clinicians. The unit was established to assist officers on the scene in dealing with individuals with mental health issues, for example, who have not done anything criminal but clearly need support and treatment.

The mobile crisis unit has now been integrated into overdose response, to support family members and recovering victims at the scene of an overdose. The unit is also geared toward trying to help overdose survivors access care in treatment facilities. However, a serious barrier is the lack of available treatment facilities for people to enter immediately when they request treatment; they can face delays of up to 30 days, said Goodwin, during which time many of them will continue injecting drugs and risk fatal overdose.

Safe Stations Program

The “safe stations” program began in April 2017 as another way to help engage people in treatment, said Goodwin. The campaign encourages people who wish to seek treatment to come to any of the police or fire stations in the county, where they can turn in their drugs and paraphernalia for disposal with no risk of being criminally charged. The mobile crisis team provides support in helping people who self-present to access treatment as quickly as possible. The program has been very successful, with 250 people presenting themselves (mainly at fire stations, caused by lingering hesitance around bringing drugs into a police station) for treatment in 2017, among whom there has been a treatment success rate of greater than 60 percent. As an additional form of outreach, everyone arrested in Anne Arundel County for any reason is issued a letter that provides information about how to get help for a drug or alcohol problem.

Educating Communities and Providers

Educating communities is critical in stemming the tide of opioid-related overdoses and fatalities in the county, said Goodwin. A vital component of the education prong of the police department’s approach is called the “Not My Child” program, a traveling panel composed of representatives from law enforcement, the fire department, the state attorney’s office, the department of health, and a treatment facility. Often the panel includes a recovering addict as well as a person who has lost a loved one to opioids (see Box 4-2 for vignettes of two of the people who frequently participate in the panel). The program was developed to counteract the prevailing attitude among the community that the epidemic will not affect their own neighborhoods and families, when in fact the epidemic is sweeping across all demographic, socioeconomic, and geographic lines and through people in all walks of life—she has seen doctors, lawyers, teachers, and law enforcement officers become addicted. The panel works to emphasize that the epidemic will ultimately affect everyone, either firsthand or through someone they know. Goodwin is passionate about

tackling the opioid epidemic because of the destructive swath that it cuts through families and communities, killing people and devastating their entire families.

According to Goodwin, they are planning to visit every high school and middle school in the county with the Not My Child panel to educate students and their parents, as well as hold open town hall meetings. Goodwin encourages parents to bring their children to the panel and start the conversation about opioids with them as young as fifth grade. She urges parents to remember that their job is not to be their child’s friend and strongly discourages them from falling into the trap of allowing their adolescents to consume alcohol and drugs in their homes, under the false assumption that they will be safe. Parents are often reluctant to attend Not My Child discussions owing to fear of social stigma, but they are trying to convince parents that the program is about promoting open

discussion around opioids and providing resources to support people who need help.

Goodwin said the police department is also working to educate physicians in order to reduce the rampant overprescription of pain medication, especially to young people. She conceded that parents instinctively want to protect their children from physical pain, but she warned that it can be dangerous for children to grow up thinking that they will never have to experience pain. She also reminds people that they do not have to take all of the opiates that are prescribed to them. However, extra pills should never be kept in the home, where they could be stolen, nor should they be flushed or thrown in residential trash. All police stations in her county have a pill drop box where people can dispose of their leftover prescriptions to be incinerated safely, and this facility has been very well used by the community, she said.

PANEL DISCUSSION ON LAW AND LAW ENFORCEMENT

Goodwin remarked that when safe needle exchange programs were first being discussed, her initial reaction was that such programs would be enabling and encouraging users, but she came to realize that people are going to use drugs until they can get treatment whether there are programs or not, so it would be better to try to prevent infectious disease and overdosing. She noted that Baltimore City has a robust SEP program in place already. She suggested that further discussions with the health departments about these SEPs and other innovative strategies may help law enforcement to become more open minded, given that their job is to prevent people from dying. Goodwin said that the messaging to the public about the benefits of SEPs should come from health departments, but law enforcement can also play a vital role in publicizing their lack of intent to charge people for possessing drug paraphernalia. Beletsky added that collaboration among sister agencies is critical. He suggested that the best way to bring law enforcement on board is to find common ground, such as by framing discussion in terms of how SEPs and harm reduction programs can benefit the police. Tapping into their intrinsic motivation opens the door to a shift in mindset about harm reduction, especially among street-level and patrol officers.

Beletsky commented on drug-induced homicide or manslaughter prosecution, a police-side policy innovation that is spreading relatively quickly in the United States. He was careful not to make any claims about Goodwin’s jurisdiction, but he relayed some of the findings of his ongoing research on this topic. Among people charged with drug-induced homicide or similar prosecutions nationally, they found that actually about half of the people charged were partners or friends of the deceased overdose

victim, shedding doubt on the idea that these prosecutions are leveled against bona fide dealers (Health in Justice, 2018; Siegel, 2017). With respect to the race of the people involved, modally it is frequently people of color as a dealer and a white victim (Siegel, 2017). The average sentence imposed is about 7 years. In the context of the opioid crisis, he said, there is a concerning disconnect between these sorts of drug-induced homicide prosecutions and Good Samaritan laws designed to encourage health seeking (Latimore and Bergstein, 2017). In research, PWUD express serious concern about being charged in this way, given the visibility of such prosecutions and how they are publicized as a way to deter drug dealers (Latimore and Bergstein, 2017). This cross-purpose messaging changes the informational environment for PWUD: on the one hand, there is an amnesty for people who call 911 but on the other, there are announcements about people doing significant time. He called into question the practice of deploying homicide investigation teams to conduct criminal investigations at the scene of an accidental overdose.

Goodwin clarified that the people being prosecuted in her jurisdiction do not fit the descriptions Beletsky provided and were not associated with each other outside of the narcotics deal, but she conceded that this may not be the case in the future. She said that when informed that their loved one would not be incarcerated for reasons related to drug use, families have told officers that they wish their family member would be locked up so that they would not be able to use any more drugs. “That would not have been the answer,” she said, “but the desperation of these parents is clear because they don’t know what else to do.”

Beletsky agreed about this level of desperation, noting that people in crisis (typically families) are leaning on the state to coerce their loved ones. Involuntary commitment is becoming increasingly prevalent in the United States, with an increase from 13 to 38 jurisdictions that authorize involuntary commitment. This has created major problems in Massachusetts, he added (Beletsky et al., 2018). In addition to objections around civil liberties, people taken into custody who have opioid use disorder should be given the option of receiving evidence-based treatment, but as a rule, they are not (Beletsky et al., 2018). As a result, with involuntary commitment and incarceration, there is a major problem with fatal reentry. That is, when people are eventually released they will have detoxed but often return to using drugs, then relapse and die at alarming rates.

The postincarceration overdose rate in Massachusetts is 56 times the background rate. People who are involuntarily committed into treatment have a 2.2 times higher risk of fatal overdose than those who enter treatment voluntarily (MDPH, 2017). “There is an ethical imperative to figure out how to deploy these interventions that actually reduce harm and not enhance it,” he argued. Given that OAT is proven to slash overdose rates

by 50 to 80 percent or more, he said, it is shocking that so many post-overdose regimens and interventions do not include access to OAT. Even in Massachusetts with its relatively robust treatment sector, resources for people in crisis to access help on demand are scarce. Before turning to coercive modalities, Beletsky advised, people should be given an opportunity to enter and to seek help voluntarily. Instead, people are being forced either into the correctional system or the civil commitment system, where they are being warehoused instead of receiving help.

Natasha Martin, associate professor in the Division of Global Public Health, University of California, San Diego, agreed that people should have access to evidence-based, voluntary treatment services, adding that the government in Tijuana has expanded funding for compulsory, abstinence-based treatments (Rafful et al., 2018). The intervention has been associated with an increase in receptive syringe sharing among PWID, and subsequent modeling work has shown that expanding those programs could fuel the HIV epidemic among PWID, compounding the problems of overdose and infectious diseases (Rafful et al., 2018).

Springer said that she works with incarcerated populations, focusing on the intersection of opioid use disorder and HIV and improving those outcomes. She pointed out that many drug dealers are also drug dependent, so prosecution will not improve their health, given that people incarcerated in the United States have 8 to 10 times the background rate of opioid use disorders, and most incarceration facilities do not provide any effective medications prior to release. The number one cause of death of all released prisoners and jail detainees is opioid overdose, she said, regardless of how long they have been incarcerated. Before incarcerating these dealers, she added, they need to be assessed for substance use disorders, HIV, and HCV, and they need to be linked to treatment and/or harm reduction as needed. Springer noted that many residential treatment programs are detox-based treatments, which are known to be ineffective and are tantamount to forced incarceration. People “failing” treatment at detox facilities should instead be linked to effective medications, like OAT or extended release naltrexone. Many women are not necessarily involved with the drug trade by personal choice, she added, so treatment interventions that involve involuntary commitment to residential treatment programs may affect their ability to stay with their children, as well as other deterrents. Springer suggested linking them with community-based treatment services instead.

Goodwin responded that the police department facilitates voluntary treatment and does not force people into treatment; she said that the health department handles the specifics of the types of facilities where people can access treatment. She added that law enforcement officers are the ones dealing with the families that have lost somebody and are look-

ing for answers about who is responsible for killing their child. It is not different than a man taking a gun and shooting them. Law enforcement officers are very selective about the cases that go forward with prosecuting; usually a person has been linked to five or six other fatal overdoses before being charged. However, they cannot turn a blind eye because law enforcement is in the business of locking up dealers who sell drugs that kill people.

Todd Korthuis, program director for the Oregon Health & Science University’s Addiction Medicine Fellowship, commented on legal issues related to patients who face incarceration after hospitalization for life-threatening infections related to opioid use, who have longer lengths of stay and costs of care because they must stay in the hospital until they finish their course of IV antibiotics. Patients who are started on appropriate treatment for opioid use disorder but are then incarcerated often experience gaps in care (as most correctional facilities do not offer buprenorphine or methadone continuation) and may also lose Medicaid coverage depending on the length of incarceration. These patients have a marked risk of relapse, overdose, and rehospitalization due to life-threatening infection. Korthuis asked if policy solutions could bridge this gap between loss of Medicaid and continuation of treatment.

Beletsky explained that laws are societal, normative statements about how substance use and its related harms are approached. The Social Security Act includes a provision that bans the use of Medicaid and Medicare dollars in correctional settings, he explained, although there is no empirical justification for doing so and it drives severe underresourcing of health care in correctional settings. A legal statutory fix is needed and is overdue, he said. Some correctional settings are trying to work with that provision by electing to suspend rather than cancel insurance policies, Beletsky added, because cancelled policies are much more difficult to reinstate than suspended policies. He emphasized the need for better bridging from correctional settings into the community and across the disciplinary disconnection between corrections, public health, and health care.

Jessica Tytel of the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office on Women’s Health remarked that women who use drugs or live in a household with PWUD are often hesitant to involve law enforcement or become involved with the legal system due to fear of losing custody of their children. Goodwin agreed and said that her department works to assure women that the goal is not to separate women from their children, but to help women create a healthy environment for them and their children. They have women-only residential facilities, which some women enter voluntarily, with their children, to receive help in overcoming their substance abuse. Anne Arundel County law enforcement visits the facilities regularly to discuss opioids as well as resources for support in deal-

ing with domestic violence. Beletsky said that it was heartening to hear Goodwin’s comments, because concerns about child protective services figure prominently in women’s willingness to access services and to call for help in an overdose situation. However, he said that it is standard practice for child protective services to become involved when people are on OAT, which can be the basis for loss of custody. Such stigma emerges not only from statute, he said, but also from nonsensical institutional policies because the known benefits of evidence-based treatment have not been translated to jurisdictions such as child protective services. He noted that many other elements of the policy environment, such as public housing policies around substance use, should be better aligned with advances in public health.

Carlos del Rio, professor of global health, epidemiology, and medicine at Emory University, remarked that there are tensions at play in communities over the change in law enforcement’s approach to the opioid epidemic. When opioid addiction and drug problems were primarily problems in African American communities, as they were for many years, the role of police was to incarcerate people. Now that opioid addiction is a problem in white communities, the role of law enforcement is to be compassionate (e.g., Good Samaritan laws). He asked how the African American community could be expected to trust the police given this history. Goodwin responded:

African American communities have got to be heard out with law enforcement listening to and validating their concerns. Then trust must be built like anything else. When trust has been broken, which takes very little and has been done repeatedly in those communities, it takes a long time to build it back up. It can’t be done overnight.

She said that they have made great strides in developing friendships and partnerships in her county, but there is still work to be done to build trust and help younger generations to see law enforcement in a different light—not as people who are going to come in and lock up their mothers or fathers or friends, their uncles, their brothers, their sisters. Officers in her department engage with communities through sports and through activities and outings with young people. del Rio described similar efforts being made by the Policing Project, an organization run by lawyers and the police that tries to serve as the glue to bring the police and the community together toward building trust. Goodwin added that the philosophy of community-oriented policing has been around for many years, but that philosophy was not upheld and trust was broken. They are working diligently to rebuild that trust and become partners with their communities, she said, because trust has to be in place before a critical incident happens.

REFERENCES

amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research. 2017. 4,864 facilities provide medication-assisted treatment in the country. http://opioid.amfar.org (accessed June 15, 2018).

Arredondo, J., S. A. Strathdee, J. Cepeda, D. Abramovitz, I. Artamonova, E. Clairgue, E. Bustamante, M. L. Mittal, T. Rocha, A. Banuelos, H. O. Olivarria, M. Morales, G. Rangel, C. Magis, and L. Beletsky. 2017. Measuring improvement in knowledge of drug policy reforms following a police education program in Tijuana, Mexico. Harm Reduction Journal 14(1):72.

Baillargeon, J., T. P. Giordano, J. D. Rich, Z. H. Wu, K. Wells, B. H. Pollock, and D. P. Paar. 2009. Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA 301(8):848–857.

Beletsky, L. In Press. 21st century cure for the overdose crisis. American Journal of Law and Medicine.

Beletsky, L., G. E. Macalino, and S. Burris. 2005. Attitudes of police officers towards syringe access, occupational needle-sticks, and drug use: A qualitative study of one city police department in the United States. International Journal of Drug Policy 16(4):267–274.

Beletsky, L., A. Agrawal, B. Moreau, P. Kumar, N. Weiss-Laxer, and R. Heimer. 2011a. Police training to align law enforcement and HIV prevention: Preliminary evidence from the field. American Journal of Public Health 101(11):2012–2015.

Beletsky, L., L. E. Grau, E. White, S. Bowman, and R. Heimer. 2011b. Prevalence, characteristics, and predictors of police training initiatives by US SEPs: Building an evidence base for structural interventions. Drug Alcohol Dependence 119(1–2):145–149.

Beletsky, L., L. E. Grau, E. White, S. Bowman, and R. Heimer. 2011c. The roles of law, client race and program visibility in shaping police interference with the operation of US syringe exchange programs. Addiction 106(2):357–365.

Beletsky, L., R. Thomas, M. Smelyanskaya, I. Artamonova, N. Shumskaya, A. Dooronbekova, A. Mukambetov, H. Doyle, and R. Tolson. 2012. Policy reform to shift the health and human rights environment for vulnerable groups: The case of Kyrgyzstan’s instruction 417. Health and Human Rights 14(2):34–48.

Beletsky, L., R. Lozada, and T. Gaines. 2013. Syringe confiscation as an HIV risk factor: The public health implications of arbitrary policing in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Journal of Urban Health 90(2):284–298.

Beletsky, L., J. Cochrane, A. L. Sawyer, C. Serio-Chapman, M. Smelyanskaya, J. Han, N. Robinowitz, and S. G. Sherman. 2015a. Police encounters among needle exchange clients in Baltimore: Drug law enforcement as a structural determinant of health. American Journal of Public Health 105(9):1872–1879.

Beletsky, L., L. LaSalle, M. A. Newman, J. M. Paré, J. S. Tam, and A. B. Tochka. 2015b. Fatal reentry: Legal and programmatic opportunities to curb opioid overdose among individuals newly released from incarceration. Northeastern University Law Journal 7(1):155–215.

Beletsky, L., E. J. Ryan, and W. E. Parmet. 2018. Involuntary treatment for substance use disorder: A misguided response to the opioid crisis. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/involuntary-treatment-sud-misguided-response-2018012413180 (accessed June 15, 2018).

Blankenship, K. M., and S. Koester. 2002. Criminal law, policing policy, and HIV risk in female street sex workers and injection drug users. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 30(4):548–559.

Bonczar, T. 2003. Prevalence of imprisonment in the U.S. population, 1974–2001. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Broz, D., J. Zibbell, C. Foote, J. C. Roseberry, M. R. Patel, C. Conrad, E. Chapman, P. J. Peters, R. Needle, C. McAlister, and J. M. Duwve. 2018. Multiple injections per injection episode: High-risk injection practice among people who injected pills during the 2015 HIV outbreak in Indiana. International Journal of Drug Policy 52:97–101.

Burris, S. 2017. Syringe possession laws. http://lawatlas.org/datasets/paraphernalia-laws (accessed June 15, 2018).

Burris, S., K. M. Blankenship, M. Donoghoe, S. Sherman, J. S. Vernick, P. Case, Z. Lazzarini, and S. Koester. 2004. Addressing the “risk environment” for injection drug users: The mysterious case of the missing cop. Milbank Quarterly 82(1):125–156.

Burris, S., A. C. Wagenaar, J. Swanson, J. K. Ibrahim, J. Wood, and M. M. Mello. 2010. Making the case for laws that improve health: A framework for public health law research. Milbank Quarterly 88(2):169–210.

Cepeda, J. A., S. A. Strathdee, J. Arredondo, M. L. Mittal, T. Rocha, M. Morales, E. Clairgue, E. Bustamante, D. Abramovitz, I. Artamonova, A. Banuelos, T. Kerr, C. L. Magis-Rodriguez, and L. Beletsky. 2017. Assessing police officers’ attitudes and legal knowledge on behaviors that impact HIV transmission among people who inject drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy 50:56–63.

CSAT (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment). 2004. Clinical guidelines for the use of buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid addiction. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 40. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. http://lib.adai.washington.edu/clearinghouse/downloads/TIP-40-ClinicalGuidelines-for-the-Use-of-Buprenorphine-in-the-Treatment-of-Opioid-Addiction-54.pdf (accessed July 23, 2018).

Dasgupta, N., L. Beletsky, and D. Ciccarone. 2018. Opioid crisis: No easy fix to its social and economic determinants. American Journal of Public Health 108(2):182–186.

Davis, C. S., S. Burris, J. Kraut-Becher, K. G. Lynch, and D. Metzger. 2005. Effects of an intensive street-level police intervention on syringe exchange program use in Philadelphia, PA. American Journal of Public Health 95(2):233–236.

Davis, C., T. Green, and L. Beletsky. 2017. Action, not rhetoric, needed to reverse the opioid overdose epidemic. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 45(Supplement 1):20–23.

Dole, V. P., M. E. Nyswander, and M. J. Kreek. 1966. Narcotic blockade. Archives of Internal Medicine 118(4):304–309.

Green, T. C., E. G. Martin, S. E. Bowman, M. R. Mann, and L. Beletsky. 2012. Life after the ban: An assessment of US syringe exchange programs’ attitudes about and early experiences with federal funding. American Journal of Public Health 102(5):e9–e16.

Green, T. C., J. Clarke, L. Brinkley-Rubinstein, B. D. L. Marshall, N. Alexander-Scott, R. Boss, and J. D. Rich. 2018. Postincarceration fatal overdoses after implementing medications for addiction treatment in a statewide correctional system. JAMA Psychiatry 75(4):405–407.

Hammett, T. M., M. P. Harmon, and W. Rhodes. 2002. The burden of infectious disease among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 1997. American Journal of Public Health 92(11):1789–1794.

Health in Justice. 2018. Drug induced homicide. https://www.healthinjustice.org/drug-induced-homicide (accessed June 15, 2018).

James, D. J., and L. E. Glaze. 2006. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Kerr, T., W. Small, and E. Wood. 2005. The public health and social impacts of drug market enforcement: A review of the evidence. International Journal of Drug Policy 16(4):210–220.

Latimore, A. D., and R. S. Bergstein. 2017. “Caught with a body” yet protected by law? Calling 911 for opioid overdose in the context of the Good Samaritan law. International Journal of Drug Policy 50:82–89.

Ling, W. 2016. A perspective on opioid pharmacotherapy: Where we are and how we got here. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology 11(3):394–400.

MDPH (Massachusetts Department of Public Health). 2017. Legislative report. Chapter 55 overdose report. Boston, MA: Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Meehan, M., and A. Kanik. 2017. Exchange of ideas: How a rural Kentucky county overcame fear to adopt a needle exchange. Ohio Valley ReSource. http://ohiovalleyresource.org/2018/03/30/exchange-ideas-needle-exchanges-grow-meet-health-threats-opioidcrisis (accessed June 13, 2018).

Peters, R. H., P. E. Greenbaum, J. F. Edens, C. R. Carter, and M. M. Ortiz. 1998. Prevalence of DSM-IV substance abuse and dependence disorders among prison inmates. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 24(4):573–587.

Rafful, C., R. Orozco, G. Rangel, P. Davidson, D. Werb, L. Beletsky, and S. A. Strathdee. 2018. Increased non-fatal overdose risk associated with involuntary drug treatment in a longitudinal study with people who inject drugs. Addiction 113(6):1056–1063.

Siegel, Z. A. 2017. Despite “public health” messaging, law enforcement increasingly prosecutes overdoses as homicides. https://theappeal.org/despite-public-health-messaging-law-enforcement-increasingly-prosecutes-overdoses-as-homicides-84fb4ca7e9d7 (accessed June 15, 2018).

Silverman, B., C. S. Davis, J. Graff, U. Bhatti, M. Santos, and L. Beletsky. 2012. Harmonizing disease prevention and police practice in the implementation of HIV prevention programs: Up-stream strategies from Wilmington, Delaware. Harm Reduction Journal 9:17.

Strathdee, S. A., J. Arredondo, T. Rocha, D. Abramovitz, M. L. Rolon, E. Patino Mandujano, M. G. Rangel, H. O. Olivarria, T. Gaines, T. L. Patterson, and L. Beletsky. 2015. A police education programme to integrate occupational safety and HIV prevention: Protocol for a modified stepped-wedge study design with parallel prospective cohorts to assess behavioural outcomes. BMJ Open 5(8):e008958.

This page intentionally left blank.