2

The Scope of the Problem

This chapter includes summaries of presentations during the workshop that focused on the scope of the opioid epidemic and its infectious consequences. Patrick Sullivan, professor of epidemiology in the Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, sketched the geography of infectious diseases related to the opioid epidemic. Natasha Martin, associate professor in the Division of Global Public Health, University of California, San Diego, described how infectious disease epidemic modeling can be used to identify the scope of the response needed to prevent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections among people who inject drugs (PWID) in the United States. An economic perspective on the implications of infectious disease treatment programs was provided by Benjamin Linas, associate professor of medicine at Boston University. Perspectives of patients and providers were offered by Seun Falade-Nwulia, assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and Veda Moore, a resident of Baltimore, Maryland.

GEOGRAPHY OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES RELATED TO THE OPIOID EPIDEMIC

Patrick Sullivan explored the geography of infectious diseases related to the opioid epidemic, particularly HIV and HCV, providing an epidemiological perspective about how infectious diseases can serve as a sentinel system for those epidemics. He also highlighted how lessons learned

from mapping HIV and HCV can inform monitoring systems for opioid use and prevention.

Importance of Infectious Diseases in the Opioid Epidemic

Many infectious diseases are associated with opioid epidemics, said Sullivan, but they vary in their usefulness as adjunct data to understand opioid epidemics. This is because of variable surveillance infrastructure, inconsistent funding of systems, and quirks related to the infections themselves that cause different degrees of sensitivity and specificity as sentinel events of needle sharing. Infectious diseases and their transmission are inextricably intertwined with needle-sharing behaviors. This relationship has important programmatic implications, such as the need to screen people who are contacted about opioid use treatment for related infectious diseases. The relationship also strengthens the value and effectiveness of programs to reduce opioid use, because concomitant reductions in needle sharing have secondary benefits of reducing the risks of related infectious diseases. Examining how data have been used successfully to inform programmatic responses to other infectious diseases, such as HIV, can also serve as models for new opioid-focused programs. Underlying social determinants of health—such as poverty, income inequality, and lack of health insurance—may also be jointly associated with the infectious diseases and opioid use epidemics, he added, and these shared, contextual factors may also inform a better understanding of the epidemics.

Infectious Diseases as Sentinels for Opioid Epidemics

Sullivan provided an epidemiological perspective on how infectious diseases can serve as a sentinel system for opioid epidemics. To illustrate quantitatively the relationships between infectious diseases and the opioid epidemic, he cited data estimating the efficiency of HIV and HCV transmission through needle sharing. For every 10,000 acts of needle sharing with an HCV-positive partner, 250 HCV transmissions would be expected; for every 10,000 acts of needle sharing with an HIV-positive partner, 63 HIV infections would be expected (Corson et al., 2013). This suggests that HCV is a more sensitive sentinel for needle sharing than HIV, he explained.1 Sullivan described five dimensions that jointly determine the usefulness of a given infectious disease as a sentinel for an opioid use outbreak in a particular geographic setting:

___________________

1 For context, Sullivan reported that the risks of HIV transmission per 10,000 acts of receptive anal intercourse and receptive vaginal intercourse are 138 and 8, respectively (Patel et al., 2014).

- Surveillance: are there surveillance systems in place?

- Specificity: are there competing causes or routes of infection? That is, are there potential competing causes or routes of infection other than needle sharing?

- Sensitivity: what is the likelihood of a single episode of needle sharing resulting in the infection?

- Latency: how long does it take from exposure to detection through a surveillance system?

- Durability: is the infectious state related to needle sharing persistent? That is, what is the likelihood that the infection will be sustained, rather than resolving spontaneously or resolving after treatment without recognition of an underlying needle-sharing event?

These five dimensions vary across HIV, HCV, skin infections, and infectious endocarditis, so he comparatively assessed the relative potentials of those infectious diseases to serve as sentinel events. There is a well-established HIV surveillance system, with HIV infection reportable in all U.S. states; routine evaluation demonstrates that HIV recording has a high level of completeness. Although HIV surveillance is good and the infection is durable, its sensitivity and specificity related to injection drug use render it less than ideal as a sentinel for an outbreak of injection drug use. In terms of specificity, only about 6 percent of new HIV infections in the country are attributable to needle sharing and, in terms of sensitivity, HIV has a relatively lower per-act risk of infection than HCV. Latency is the weakest dimension for HIV as a sentinel: in the absence of a screening program, there is a long latency period before the infection becomes clinically evident after the infection has been established.

The HCV surveillance system is less well developed, and many areas lack the support needed to report HCV cases with high levels of completeness, although there are several pilot-enhanced surveillance sites that are making progress in this regard. However, HCV is a more specific sentinel than HIV, because most new HCV infections are related to injection; HCV is also a more sensitive sentinel than HIV, because the per-act risk of transmission is higher. HCV and HIV are similar in terms of latency and durability. Skin infections and infectious endocarditis do not have surveillance systems and probably are not very sensitive or specific, said Sullivan, although they both have quite short latent periods. However, the durability is low for both types of infection, with skin infections being the most likely to resolve spontaneously or after treatment but without recognition of the underlying cause.

Mapping the HIV Epidemic

Sullivan described AIDSVu, a project that has been mapping the HIV epidemic in the United States for 8 years.2 It is a compilation of interactive online maps that allows users to visually explore the HIV epidemic in the United States alongside critical resources, such as HIV testing and treatment center locations. AIDSVu’s mission is to make HIV prevalence data widely accessible, easily understandable, and locally relevant. AIDSVu provides users with an intuitive, visual way to connect with complex information about persons living with an HIV diagnosis. National, state, and local maps provide data on the number of people living with an HIV diagnosis by state, county, zip code, census tract, and neighborhood, as well as the number of people newly diagnosed with HIV by state and county, year by year. These data are also mapped alongside data on social determinants of health (e.g., poverty, insurance, and education) and on HIV transmission modes. To ensure that these are “data for action,” AIDSVu also provides service locators for centers that provide HIV testing, treatment, and preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) as well as information about HIV prevention, vaccine, and treatment trials sites that are funded by the National Institutes of Health. AIDSVu also provides information about housing opportunities for people with HIV.

Sullivan reported that in recent years, the overall rates of new HIV diagnoses according to transmission category have been stable to decreasing. However, this slightly contracting number of new HIV diagnoses is predominantly driven by male-to-male sexual contact. Between 2010 and 2015, the proportion of new diagnoses of HIV infection among adults and adolescents (in the United States and six dependent areas) attributed to male-to-male sexual contact increased from 60 percent to 66 percent. However, the same period saw decreases in the proportions of diagnoses attributed to injection drug use (representing slightly more than 5 percent) and those attributed to heterosexual contact with a person known to have (or at high risk for) HIV infection (less than 25 percent).3

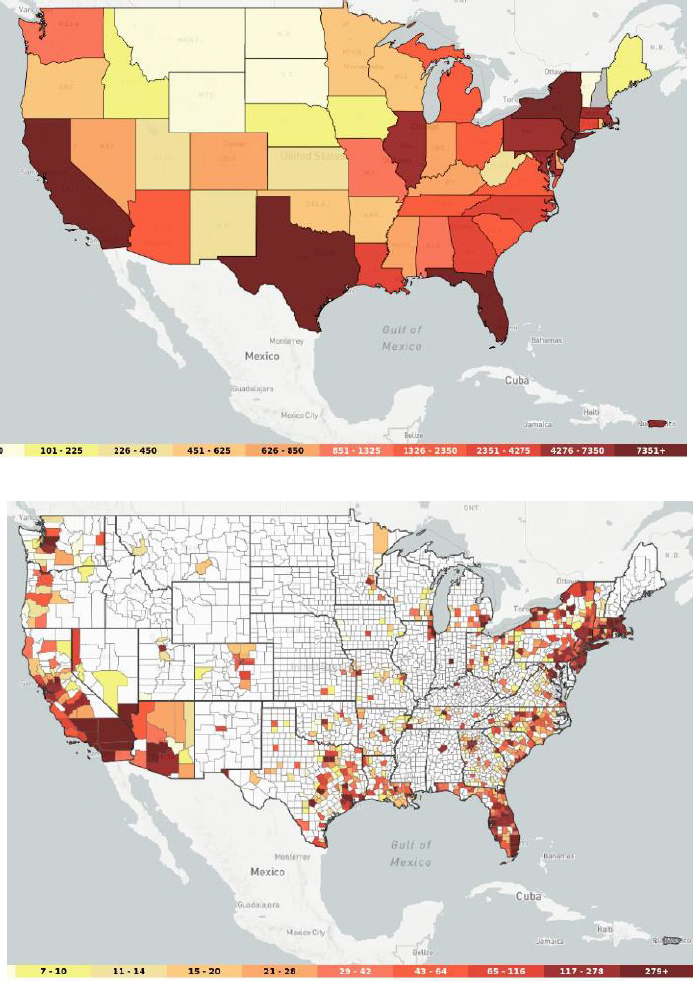

Sullivan explained that AIDSVu allows researchers to focus specifically on people living with diagnosed HIV attributed to injection drug use. The top map in Figure 2-1 shows the results of decades of accumulation of HIV infections associated with injection drug use. States that have darker shading represent the intersection of high prevalence of HIV related to injection drug use with large populations. The bottom map in Figure 2-1 depicts the numbers of HIV cases attributable to injection drug use at a finer level of geographic detail. The top map suggests, owing to the shad-

___________________

2 The project is available online at https://aidsvu.org (accessed April 15, 2018).

3 Data have been statistically adjusted to account for missing transmission category; “other” transmission category not displayed as it comprises less than 1 percent of cases.

SOURCES: As presented by Patrick Sullivan at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 12, 2018; AIDSVu, 2018.

ing, that the states that were highly affected were uniformly affected, but the bottom map reveals that a large number of counties (shown in white) had only four or fewer people living with HIV attributed to injection drug use. This demonstrates the extent to which PWID have historically been geographically concentrated in urban areas in the HIV epidemic.

The AIDSVu maps can also be used to illustrate differences in HIV between men and women, Sullivan added. In a state-by-state comparison, the rates of men living with diagnosed HIV infection in 2014 were higher than the rates of women. However, the proportion of those infections attributed to injecting drugs is greater for women than for men. At an even more local level of geographic granularity, these types of maps can be useful when correlated with service data and with indicators of substance abuse. He illustrated this by presenting a map of the numbers of new HIV diagnoses in the Atlanta metropolitan statistical area—that is, areas where HIV testing and HIV prevention services are most needed. When overlaid with the locations of the major interstates in the city, it reveals that the greatest numbers of new diagnoses are in the city’s southwest quadrant. Factoring in the density of residents in that quadrant by race reveals that the area has a largely African American population. Overlaying the coordinates of HIV testing locations provides a visualization of the distribution of HIV testing locations, which should (ideally) be aligned with areas of the highest HIV incidence, Sullivan said. While the distribution matches the need in the areas of the southwest quadrant that are closest to the center of the city, areas further away from the city center have high rates of new HIV diagnoses (and presumably high incidence) without high coverage of testing sites.

Using the same base map of new HIV diagnosis rates, he overlaid the locations of PrEP providers. It demonstrates that most PrEP providers are located in the northern parts of the city, where the intensity of new diagnoses is lower, and illustrates the substantial gap in PrEP provision in the southwest quadrant, where incidence is high. Based on these findings, a colleague of Sullivan at Emory University has developed a system to reach people who live in areas without brick-and-mortar PrEP service provision locations by delivering PrEP entirely through telemedicine and mail-out kits. Mapping these types of gaps between indicators of need and service provision locations underscores the need to develop more innovative ways to place services where they are most needed, through mobile vans or telemedicine, said Sullivan.

Mapping the Hepatitis C Virus Epidemic

According to Sullivan, preliminary analyses suggest that there are correlations between HCV data and opioid abuse indicators, some of

which probably represent certain long-term historical trends, but they may also highlight departures between data about historical infections and more recent indicators that may suggest emerging areas of epidemics. HCV is an infectious disease that has interesting dynamics with substance use because the per-act risk of transmission is quite high, he said, but HCV surveillance is not yet systematic enough. He explained that broadly, the natural history of HCV has two phases. After an exposure to HCV and the establishment of infection, about 25 percent of people will have a mild acute illness that resolves itself, while 75 percent may have no symptoms. About one in four people go on to spontaneously clear their active infection while maintaining antibodies to HCV; three out of four people go on to develop lifetime infection with progressive liver damage. Diagnostics have two key formats: an antibody test that screens for lifetime exposure to HCV (even if the infection is cleared) and an RNA detection test that diagnoses current infection with HCV that needs to be treated.

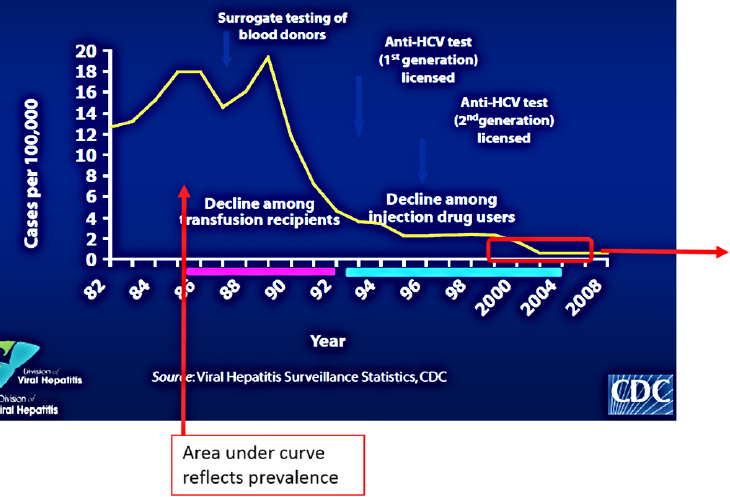

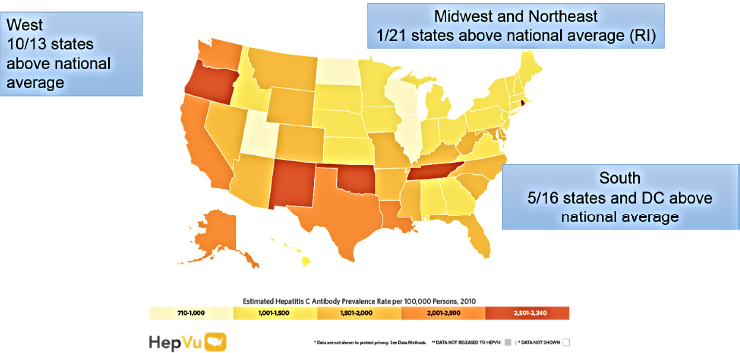

Sullivan used a side-by-side comparison to demonstrate that there are actually two different HCV epidemics in the United States. Figure 2-2 shows the broad arc of the recent history of the HCV epidemic in the United States. In the early 1980s, levels of acute HCV infections were high and largely attributed to blood transfusions. Surrogate testing for HCV by testing blood levels of the liver enzyme alanine aminotransferase was introduced in October 1986, and testing for the hepatitis B core antigen was introduced in January 1987. Those interventions resulted in a precipitous drop in transfusion-related HCV transmission through the early 1990s. The subsequent introduction of anti-HCV antibody tests licensed during the mid-1990s supported further prevention efforts and drove further declines in the remnant HCV cases among injection drug users, which dropped to a very low level by the mid-2000s, as indicated by the red box in the figure. Figure 2-3 provides a more complete picture, he explained, of the reductions in acute HCV incidence stratified by age group. The incidence declined through the period of 2003 to 2005—dropping as low as 0.5 per 100,000 population. However, incidence then began to resurge in all age groups, but especially among people age 20 to 39 years. Sullivan surmised that a substantial part of this reemergence is related to opioid epidemics.

Sullivan remarked that HCV has interesting characteristics as a potential indicator for better understanding opioid epidemics, but without national surveillance, it has not been possible to estimate HCV prevalence across the United States in a systematic way. He reported that his colleagues Eli Rosenberg and others at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have worked on this problem using data from four population-based data sources to develop estimates of HCV prevalence that can be compared from state to state (Rosenberg et al., 2017). The work

NOTES: The area under the curve reflects prevalence. HCV = hepatitis C virus.

SOURCES: As presented by Patrick Sullivan at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 12, 2018; CDC, 2017.

draws on four primary data sources, he said. The first was the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a national probability sample that includes antibody testing for HCV as well as RNA testing. The other three were the 2010 U.S. Census, U.S. Census intercensal data, and the National Vital Statistics System; the latter provides data on deaths in which HCV was listed as an underlying or contributory cause of death.

The general approach was to first use the NHANES data to estimate the number of people living with HCV antibodies in the United States, and then to allocate the NHANES total of HCV cases to each state based on the distribution of demographic variables through a process of indirect standardization. Rosenberg and colleagues (2017) identified 24 demographic strata based on known characteristics of HCV, such as men, African Americans, and people born between 1945 and 1965 are most heavily affected. Then they analyzed each state’s distribution within these demographic strata and provisionally allocated HCV cases from the national epidemic to each state based on the population character-

istics. Because the demographic structure of states is not the only driver of HCV levels, the CDC team developed the other state effects using data from the death records to look for deaths related to HCV that were greater than the number predicted by the demographic characteristics. To calculate the state effects, the predicted HCV death rate in each stratum in each state was compared to national averages for each strata. The provisional NHANES case allocations were multiplied by the state effects in each strata, providing estimates of HCV cases within each state and each strata. The number of estimated cases was divided by the population (per the 2010 U.S. Census) to calculate the estimated prevalence in each state. According to Sullivan, this statistical approach has the advantage of exactly standardizing the two data systems, both of which are population based, to each state. Consequently, nearly all residual biases are related to the underlying data and data systems, rather than the statistical model choice. This method, combined with the large-size data sets, permitted the detection of higher-order demographic group and state interactions.

The outcome of this work was mapped to represent the total number of people with HCV antibodies present in 2010 (around 3.9 million), around 25 percent of whom would have cleared their infection, leaving around 2.8 million people living with chronic HCV at the turn

NOTES: The area under the curve reflects prevalence. yrs = years.

SOURCES: As presented by Patrick Sullivan at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 12, 2018; CDC, 2017.

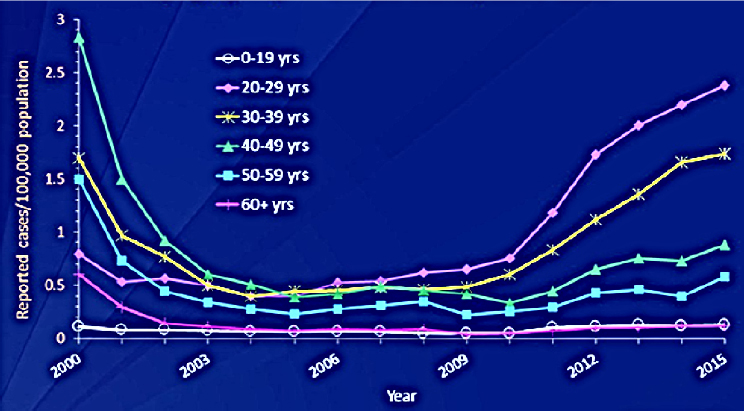

NOTE: DC = District of Columbia; RI = Rhode Island.

SOURCES: As presented by Patrick Sullivan at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 12, 2018; HepVu, 2018.

of the decade (HepVu, 2018) (see Figure 2-4). Sullivan noted that this largely represents an accumulation of older infections—some of which are decades old. A map that takes into account both the prevalence of HCV within states and the population size reveals a more detailed picture. States such as New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Tennessee emerge as having higher estimates of HCV prevalence relative to other states, he noted, which may to some extent be a historical depiction of HCV. There are also fairly clear regional patterns: the West has 10 of 13 states above the national average of HCV prevalence, but Rhode Island (which has a relatively high urban-to-rural ratio) is the only state in the entire region of the Midwest and the Northeast to have prevalence above the national average. In the South, 5 of 16 states and Washington, DC, are above the national average. He added that data on prevalence and mortality data from HepVu can also be used to illustrate differences between men and women. In general, men are affected by HCV to a greater extent than women, which is borne out in the state-by-state mortality data from 2014 in which the mortality cases attributed to HCV among men exceed the mortality cases among women.

Opioid Indicators and Correlation

Infectious diseases can serve as indicators in a surveillance approach aimed at better characterizing epidemics, Sullivan said, but they also can

figure into a more broad, comprehensive approach to surveillance. In addition to HIV and HCV, other possible indicators include infectious endocarditis, antecubital abscesses, skin infections, drug-related overdose deaths, naloxone units used, needle sales in pharmacies, use of drug treatment services, and hotline calls. These and many other indicators may be helpful in trying to understand opioid epidemics but also in providing early warnings when there are emergent situations that need attention. Sullivan said the overall aim should be to develop a comprehensive set of potential indicators, both infectious and noninfectious, that have been evaluated with respect to their potential performance as part of a system to direct attention to needle sharing, for example. Like HIV and HCV, each of these indicators should be evaluated for their usefulness along the dimensions of surveillance, sensitivity, specificity, latency, and durability. For example, there are questions around the sensitivity of drug-related overdose deaths. Many coroners do not mark deaths as overdoses because they want to spare the family from stigma and allow families to receive life insurance compensation (which is not provided if a person dies while engaged in illegal activity). These deaths may be coded as aspiration or heart attack, which are truthful data that nonetheless lead to undercounts of actual overdoses.

To address this, states, including Georgia and Kentucky, are considering putting a tick box on the reporting form (but not on the death certificate) that would allow coroners to indicate a suspected overdose and would be available as a surveillance mechanism. Because of intertwined issues of depression and substance use, he said, there is also concern that overdoses designated as unintentional might actually be intentional. Ideally, medical records would capture substance abuse data for people who present with infectious diseases like endocarditis, cellulitis, and abscesses, but usually they do not. He reported that as a step toward improving specificity, his colleagues have developed an algorithm based on location to detect injection-related infectious endocarditis, cellulitis, and abscesses, which includes excluding cases with other known etiologies.

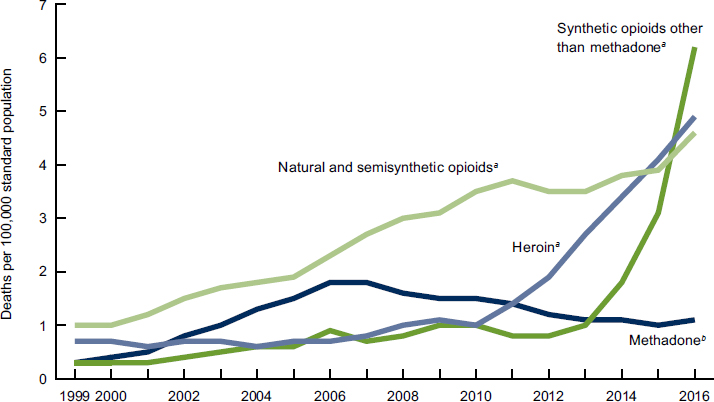

Having disclosed the indicators’ limitations in terms of drug overdose death rates as well as the likelihood of substantial undercount, Sullivan reported that since the turn of the century, there has been a consistent increase in the age-adjusted overdose death rates in the United States, which have consistently been higher in men than in women. Figure 2-5 illustrates the breakdown of age-adjusted drug overdose rates by opioid category. He explained that when considered as a surveillance system, such data suggest that the specificity of drug overdose deaths as an indicator of certain opioid-related injections has likely changed over time. In the past 6 years, for example, overdoses attributed to synthetic opioids (other than methadone) have overtaken deaths attributed to other types

NOTES: Deaths are classified using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision. Drug-poisoning (overdose) deaths are identified using underlying ICD-10 cause-of-death codes X40–X44, X60–X64, X85, and Y10–Y14. Drug overdose deaths involving selected drug categories are identified by specific multiple-cause-of-death codes: heroin, T40.1; natural and semisynthetic opioids, T40.2; methadone, T40.3; and synthetic opioids other than methadone, T40.4. Deaths involving more than one opioid category (e.g., a death involving both methadone and a natural or semisynthetic opioid) are counted in both categories. The percentage of drug overdose deaths that identified the specific drugs involved varied by year, with ranges of 75–79 percent from 1999 to 2013 and 81–85 percent from 2014 to 2016.

a Significant increasing trend from 1999 to 2016 with different rates of change over time, p < 0.05.

b Significant increasing trend from 1999 to 2006, then decreasing trend from 2006 to 2016, p < 0.05.

SOURCES: As presented by Patrick Sullivan at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 12, 2018; Hedegaard et al., 2017.

of agents; there has also been an increase in the representation of heroin in these drug overdose deaths. These trends have changed the performance characteristics of these indicators in terms of their relationships to opioid epidemics. Sullivan noted that in terms of indicators, opioid overdose emergency department (ED) visits may offer a potentially interesting source of data to understand trends in opioid use. Through CDC’s

Enhanced State Opioid Overdose Surveillance Program, opioid overdose ED visits are tracked and reported in 16 states.4 The data show the heterogeneity in trends among the included states.5 However, it falls well short of a comprehensive surveillance system because 34 states do not report data.

Correlation of Service Data and Opioid Indicators

In terms of the correlation between service data and opioid indicators, Sullivan said that there is a wealth of downloadable data about substance abuse treatment locations available from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). These data can be used to find substance abuse and mental health service location points and sort them by service provisions, including

- types of care (e.g., substance abuse treatment, detoxification, or acceptance of clients on opioid medication);

- service settings (e.g., hospital inpatient, outpatient, or day treatment);

- payments accepted (e.g., Medicaid, private insurance, or cash);

- payment assistance availability (e.g., sliding fee scale or payment assistance);

- special programs or groups covered (e.g., veterans, seniors, persons with HIV/AIDS, or persons who have experienced trauma);

- age groups accepted;

- gender accepted;

- buprenorphine physicians; and

- health care centers.

Researchers have made a first attempt to combine data from SAMHSA with The Foundation for AIDS Research’s (amfAR’s) opioid indicator database (another online resource), said Sullivan. They created a base map to represent the intensity of drug overdose deaths per 100,000 overlaid with the locations of substance abuse treatment facilities that accept

___________________

4 See https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/opioid-overdoses/infographic.html#graphic2 (accessed May 1, 2018).

5 Sullivan said that among the states reporting percent changes from July 2016 through September 2017, five states had a decrease in ED visits (Kentucky, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and West Virginia); three states had an increase of between 1 and 24 percent (Missouri, Nevada, and New Mexico); four states had an increase of between 25 and 49 percent (Indiana, Maine, North Carolina, and Ohio); and four states had an increase of greater than 50 percent (Delaware, Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin).

clients on opioid medications and prescribe or administer buprenorphine and/or naltrexone (per the SAMHSA database). At a high level, it shows that some areas are fairly well served in terms of current substance use provision locations while other areas may need more providers, such as the area encompassing Indiana, Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia. He emphasized that this effort to “mash up” indicators generates hypotheses in the sense that they lead to questions about how service needs are (or are not) being met, including commute time required for certain types of services.

Comparisons corroborate state-level data on HCV prevalence rates, he reported. In the map of HCV antibody prevalence in 2010 (see Figure 2-4), certain states, including New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Tennessee, stand out, albeit largely owing to historical trends in HCV transmissions. When opioid-related deaths per 100,000 in the same year are mapped, some of the same areas continue to stand out. However, there is a cluster of counties around Kentucky and West Virginia that seem to be different than the historical data. This demonstrates how comparing data sources can identify areas where more recent clusters of needle-sharing behavior would show up in the overdose deaths, but would not have the same prominence in the map of historical antibody prevalence. According to Sullivan, these analyses “give us an idea about this interplay between infectious diseases—which have their own timelines and chronicities and stories—and other indicators of opioid use [that can] lead us to generate hypotheses about where we may have opportunities to improve service provision.”

Sullivan concluded by arguing that improved surveillance systems are needed to ensure consistent and complete reporting for acute HCV cases, as well as for other infectious diseases and for indicators of opioid use as parts of a broader, more comprehensive, national surveillance system. This would allow for maximizing indicators according to their particular strengths in terms of latency, sensitivity, specificity, and so forth to provide a better overall view. He emphasized that indicator data for HCV, HIV, and opioids suggest that there are important differences between men and women, which call for stratified analyses around the idea that women may use opioids in different ways that might require different programmatic interventions.

Discussion

Carl Schmid of the AIDS Institute asked whether HBV is also increasing in many areas because of the opioid epidemic and injection drug use. Sullivan replied that as new infectious diseases emerge and are characterized descriptively as outbreaks, one of the challenges is figuring out how

they fit into the picture more broadly. However, it can be a long, slow process for surveillance systems to mature and for indicators to develop as they have for HIV and HCV. In the meantime, he suggested leveraging the contributions of the existing surveillance systems and indicators, upon which descriptions of outbreaks like HBV can be layered.

Judith Feinberg of West Virginia University suggested that heat maps by county serve as adequately sensitive indicators to demonstrate that in the southern part of West Virginia there is almost a complete correlation for acute HCV and overdose mortality. Sullivan replied that national-level heat maps can provide a broader perspective and inform hypothesis generation, but they are not intended to replace the important work done at the local level. Local-level work enriched by nuanced understanding of local context and conditions can be used to develop the picture in greater geographic resolution and identify relevant indicators. All surveillance is fundamentally local, he added, so these types of observations are critical to health departments’ responses.

Dawn Fishbein, infectious disease physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center, warned that because much of the disseminated surveillance data is older, funding agencies may have the false impression that there are not problems in areas that are known to be affected. Sullivan suggested investing more in surveillance, particularly for HCV. The data he presented from HepVu represents data through 2010, but further data have now been obtained from NHANES that will allow those estimates to be extended by another 5 or 6 years and posted on HepVu. Data will also be updated to reflect emerging signals that are believed to represent increasing numbers of recent infections in younger people, because signals differ demographically in the ways to indicate transmissions in more contemporary opioid-related outbreaks.

A balance needs to be struck, Sullivan said, between striving for more current surveillance data and using the existing data in other ways in the interim. Another delicate balance is needed between state-level and national-level surveillance analyses of data. State-level work is always better informed about the issues at play in each state, but before HepVu estimates were developed, many states had no state-specific estimates of HCV based on surveillance data. He noted that high-quality scientific data can be developed in different ways to address existing gaps in surveillance and limitations in different states. It is important to recognize the limitations of data and address them synthetically, he added. All surveillance data require triangulating with multiple approaches and data sources. When state-level perspectives differ from those provided by a national modeling approach, Sullivan said, it provides opportunities for states to learn about the surveillance system and for national researchers to learn about modeling approaches. Fishbein also suggested that

prescription opioids should be explored as a marker for the epidemic in injection opioid use, given the dearth of good surveillance data.

Josiah “Jody” Rich, professor of medicine and epidemiology at Brown University, commented that syringe access is a key variable. Rhode Island, for example, is an outlier in the data due to its syringe access laws. During the 1990s, possession of a single syringe was a felony offense vigorously enforced and punishable by 5 years of incarceration. People who were injecting drugs would use syringes and then leave them behind, where they would continue to be used by other people. As a result, Rhode Island was one of only four states at the time with more than half of AIDS cases related to injection drug use. He also suggested law enforcement data on drug testing could be useful. Sullivan said that law enforcement data can be very helpful within a jurisdiction, but they are driven by local policing decisions to the extent that biases become quite large across jurisdictions and across states. However, they would need to be analyzed within a framework that examines such data as surveillance systems using CDC’s guidelines for evaluation for timeliness, availability, sensitivity, specificity, and completeness of reporting in order to characterize those biases.

Corinna Dan of HHS noted that CDC had recently released new estimates on opioid overdose deaths, which increased substantially between 2016 and 2017. She asked if the proliferation of fentanyl and fentanyl analogues and the changing drug use picture will affect the way that drug overdose tracks with HCV. Sullivan replied that when multiple indicators are rolled together and change, then interpreting those changes only makes sense if the contributions of the underlying components remain fairly proportional. This calls for looking at more granularity and perhaps trying to standardize the contributions of different components to overdose deaths, he said. In practice, however, changes such as the emergence of fentanyl and fentanyl analogs will muddy the water with respect to interpreting trends over time. Given that the landscape will likely continue shifting, he suggested prospectively breaking those changes out and looking at more granular levels of available cause-specific data to better understand the mix of the actual substances used and the way they are compounded.

Carlos del Rio, professor of Global Health and Medicine at Emory University, noted that the Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs)6 is a very strong, robust surveillance system that has been ongoing since the mid-1990s. He suggested finding ways to integrate and layer such

___________________

6 Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) is CDC’s active laboratory- and population-based surveillance system for invasive bacterial pathogens of public health importance. More information is available at https://www.cdc.gov/abcs/index.html (accessed March 12, 2018).

systems to look at opioid trends and epidemics, citing a recent paper that suggests a relationship between opioid use and pneumococcal infections that was unexpected (Wiese et al., 2018).

MODELING THE PREVENTION OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES AMONG PEOPLE WHO INJECT DRUGS

In her presentation, Natasha Martin described how infectious disease epidemic modeling can be used to identify the scope of the response needed to prevent HIV and HCV infection among PWID in the United States. She began by describing the effectiveness of harm reduction interventions in preventing two of the main infectious disease consequences of opioid addiction, HCV and HIV. Opiate agonist therapy (OAT) is highly effective at preventing fatal overdose among PWID. OAT’s effectiveness in reducing an individual’s reported injecting risk behavior has been known for many years, but only relatively recently has evidence emerged about the effectiveness of this intervention against HIV incidence and HCV incidence among PWID. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that OAT reduces an individual’s risk of acquiring HIV by about 54 percent, as well as reducing an individual’s risk of acquiring HCV by about half (Aspinall et al., 2014; MacArthur et al., 2012; Platt et al., 2017). The evidence for syringe service programs is slightly more mixed, but systematic reviews and meta-analyses have indicated that they are associated with a reduction in HIV incidence by 34 percent and reduction in an individual’s risk of acquiring HCV by as much as 76 percent. She noted that the latter estimate pertains to the efficacy among studies conducted in Europe; the evidence from North America is less strong and quite mixed. The Cochrane systematic review found that combined harm reduction (that is, OAT plus high-coverage needle and syringe programs) could reduce an individual’s risk of acquiring HCV by nearly 75 percent.

HIV treatment is effective at both reducing HIV-related mortality and reducing HIV transmission among PWID, Martin explained, and harm reduction and HIV treatment can work synergistically to lead to better outcomes and reduce HIV transmission. For example, a systematic review and meta-analysis found that OAT is associated with a 69 percent increase in the recruitment rate of individuals onto antiretroviral treatment (ART), a two-fold increase in ART adherence, a 23 percent decrease in the odds of ART attrition, and a 45 percent increase in the odds of viral suppression (Low et al., 2016).

New direct-acting antiviral therapies for HCV are highly effective and highly tolerable, said Martin. Cure rates for PWID treated for HCV reach 94 percent among individuals who are on OAT as well as among those who are not (Dore et al., 2016; Grebely, 2017; Grebely et al., 2016; Zeuzem

et al., 2015). However, HCV treatments are restricted by reimbursements to health care providers, both in the United States and worldwide. For example, 2017 Medicaid restrictions for HCV therapy in many states impose restrictions based on drug and alcohol use, including abstinence-based restrictions, despite clinical recommendations that recent drug use should not be a contraindication to HCV treatment. Some states also impose restrictions based on liver damage, with treatment prioritized for individuals with more advanced fibrosis. Martin explained that this is relevant because the PWID infected with HCV who pose the greatest risk of transmitting HCV to others tend to be recent drug users and they tend to be younger, with less advanced liver disease. Having restrictions based both on liver damage and on abstinence in place exclude most PWID from HCV therapy eligibility. Despite highly effective therapies for HCV, few PWID at the core of the HCV epidemic receive treatment in the United States.

Modeling Elimination of Hepatitis C Among People Who Use Drugs

Martin explored what is needed to eliminate HCV among PWID in the United States, noting that the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the World Health Organization (WHO) have both set the goal of eliminating viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030, with specific impact targets of reducing the number of new HCV and HBV cases by 90 percent and reducing HCV- and HBV-related mortality by 65 percent (NASEM, 2017; WHO, 2016). As more national and state governments become interested in achieving these elimination targets, epidemic modeling can contribute to understanding the exact level of intervention and what mixture of interventions will be required to achieve these targets. Epidemic modeling is useful for forecasting the epidemics into the future as well as assessing what level of intervention is required to reduce new infections. Epidemic modeling is unique in that it mechanistically models a disease epidemic among individuals so that incidence is generated as an output. Reaching an incidence target requires epidemic modeling that generates projections of future incidence. This enables an assessment of what level of interventions are needed to prevent new infections.

Treatment as Prevention for Hepatitis C

Epidemic models have been used successfully to look at the effects of various coverage levels of interventions on the HCV epidemic among PWID, said Martin. Her research group has done work showing that harm reduction—although very important in averting infections in set-

tings where it has been scaled up—is not likely to be able to achieve HCV elimination in isolation (Martin et al., 2013a; Vickerman et al., 2012). HCV response requires additional interventions layered on top of harm reduction, she explained. Given that HIV treatment is prevention, Martin said, substantial interest has been garnered in HCV treatment as prevention. Unlike HIV treatment, HCV treatment has the additional advantages of being finite and curative. However, because HCV treatment does not prevent reinfection, there are concerns about the reinfection risk and the economic consequences of treating individuals who may become reinfected and require re-treatments. She and others have carried out theoretical modeling work indicating that modest increasing levels of HCV treatment among PWID could substantially reduce HCV prevalence and incidence among that population (Martin et al., 2013a,b; Zelenev et al., 2018). “We don’t need to treat everyone . . . modest levels of treatment could actually have a substantial impact on the epidemic,” she said.

Martin compared work on HCV prevention among PWID carried out in one urban setting and two rural settings that are facing different types of epidemics: San Francisco, California; Perry County, Kentucky; and Scott County, Indiana. All of the settings have high prevalence among PWID, but their incidence rates are very different. The country is highly heterogeneous in terms of its HCV epidemics among PWID, she said, which necessitates responding with approaches that are specific to the setting. San Francisco has a very high prevalence of HCV among PWID, Martin said, with more than 80 percent of that population chronically infected. At around 12 per 100 person-years, the HCV incidence rate in the city is high in absolute terms, but low relative to the high prevalence; in fact, it has the lowest stable incidence of all three settings. Modeling results for HCV chronic prevalence and HCV incidence among PWID in San Francisco predict a fairly stable epidemic, she reported (Fraser et al., 2018). That is, without any additional interventions, the chronic prevalence would be sustained at around 70 to 80 percent. Further increasing harm reduction would have a relatively modest effect because the city already has high coverage of syringe service programs. But despite the extremely high prevalence of HCV among PWID, she maintained, WHO incidence elimination targets for 2030 could be achieved by providing a full harm reduction package with relatively modest treatment rates of about 50 per 1,000 PWID per year.

Martin explained that Perry County, Kentucky, also has a high prevalence rate of HCV among PWID, although it has a moderate but stable incidence rate of around 20 per 100 person-years. The HCV epidemic is slowly expanding among PWID, but in contrast to San Francisco, modeling predicts that scaling up to full harm reduction (syringe service programs plus medication-assisted treatment [MAT]) would substantially

reduce incidence and prevalence by 50 percent or more by 2030 (Fraser et al., 2018. However, full harm reduction would not achieve the elimination target of a 90 percent reduction in incidence by 2030. Achieving elimination is possible, she said, but it would require a scale up of harm reduction combined with HCV treatment at rates of less than 50 per 1,000 PWID annually.

Scott County, Indiana, also has a relatively high prevalence of HCV among PWID, coupled with an expanding epidemic. Incidence is highest of the three settings—greater than 40 per 100 person-years—and the rate is increasing rather than stable. Modeling of chronic prevalence indicates that between 2008 and 2010, there was a temporary drop in chronic prevalence among PWID that was likely attributable to the expansion of drug use in the population resulting in an inflow of new susceptible (not infected) injectors (Fraser et al., 2018). After 2010, however, chronic prevalence increased substantially, to around 55 percent in 2015, owing to the increasing HCV transmission risk in that previously noninfected population. The model projects a continued increase in HCV chronic prevalence in Scott County that could rise to roughly 83 percent by 2030 in the absence of intervention. The projected burden of infection is substantial, she said, and requires an urgent public health response. Full harm reduction (50 percent MAT plus 50 percent high-coverage syringe services programs) is key to prevention and can reduce both chronic prevalence and incidence, she added. However, it cannot reverse the increasing incidence trend, which can only be stabilized with the expansion of harm reduction. Combined harm reduction and HCV treatment, at a rate of 20 per 1,000 PWID per year, would stabilize the prevalence, and then any additional treatment could drive down the prevalence as well as drive down the incidence.

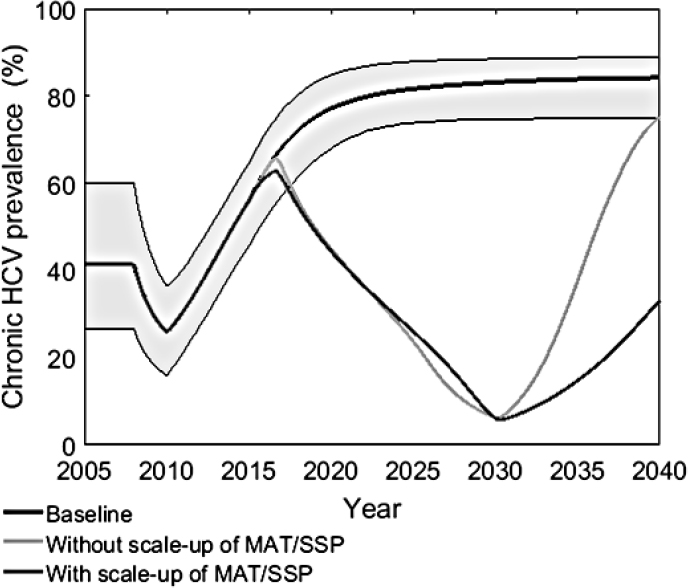

The Scott County epidemic also highlights the importance of retreating reinfections, said Martin, despite concern about the high costs of treatment. If re-treatment of reinfections is not allowed in Scott County, then the HCV epidemic could rebound because of reinfection (see Figure 2-6). Provision of high-coverage harm reduction could maintain the treatment-as-prevention effect and sustain a low prevalence and incidence of infection, but it would be insufficient to reach the National Academies’ and WHO’s target of 90 percent reduction in incidence. Tackling these epidemics, she argued, will require willingness to re-treat reinfections in addition to comprehensive harm reduction and treatment.

This comparison among settings underscores the need for more intervention in locations where epidemics are expanding, Martin remarked. The rates of treatment per 1,000 PWID that would be required to achieve a 90 percent reduction in incidence by 2030 varies according to the stability of the epidemic. With a treatment-as-prevention strategy that is not cou-

NOTE: Figure shows chronic HCV prevalence per 100 person years at the baseline and with and without MAT/SSP scale up if treatment is stopped in 2030 when 90 percent decrease from 2016 is achieved.

HCV = hepatitis C; MAT = medication-assisted treatment; SSP = syringe services program.

SOURCE: Fraser, H., J. Zibbell, T. Hoerger, S. Hariri, C. Vellozzi, N. K. Martin, A. H. Kral, M. Hickman, J. W. Ward, and P. Vickerman. 2018. Supplementary Figure S4a from Supporting Information for “Scaling up HCV prevention and treatment interventions in rural United States—Model projections for tackling an increasing epidemic.” Published online in Addiction 113:173–182. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/add.13948 (accessed June 13, 2018).

pled with harm reduction scale up, treatment rates of below 75 per 1,000 PWID annually could achieve elimination in San Francisco and in Perry County (Fraser et al., 2018). Because the incidence is higher and increasing in Scott County, the required treatment rates need to be threefold higher than if it were a stable incidence setting. However, the treatment rates required to achieve elimination could be even lower with combined

harm reduction scale up and HCV treatment, she reported. It would cut in half the number of treatments needed in Perry County and Scott County, although there would be slightly less effect in San Francisco owing to its higher baseline-level needle services program (NSP) coverage. Martin stated that with regard to whether specific PWID should be targeted for HCV treatment, the answer is complicated by variable network effects among PWID (see Box 2-1).

Modeling Prevention of HIV Among People Who Inject Drugs

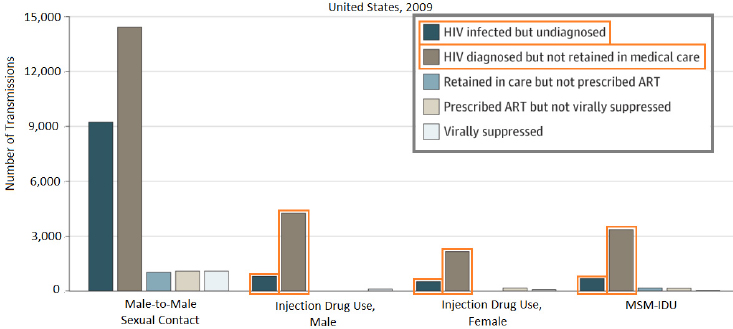

Interventions for preventing HIV among PWID in the United States are similar to those used to prevent HCV, said Martin. Various studies on harm reduction and treatment have looked at variances in the care cascade, said Martin. One study used modeling to identify the care continuum gaps that contribute most strongly to HIV transmission (Skarbinski et al., 2015). The study estimated the numbers of new transmissions among individuals within different groups (including those who engage in male-to-male sexual contact, men and women who use injection drugs, and men who have sex with men and also inject drugs) at different steps of the care cascade: HIV infected but undiagnosed; HIV diagnosed but

not retained in medical care; retained in care but not prescribed ART; prescribed ART but not virally suppressed; and virally suppressed. Among PWID, the vast majority of new transmissions come from HIV-diagnosed individuals who are not retained in medical care. In addition to illustrating the need to initiate more people on ART, she noted, it pinpoints this step in the care cascade as the best target to have the strongest prevention response. The second group to target are individuals who are HIV infected but undiagnosed, which underlines the need for both screening and linkage to care in the population (see Figure 2-7).

Another study performed a similar analysis with data from New York City aimed at identifying the care continuum gaps contributing to HIV transmission among PWID. Their modeling found that in that city, undiagnosed HIV-infected PWID represent 33 percent of the total population of PWID, but they contribute more than half of the new infections. This means that in New York City, the undiagnosed population should be targeted to disrupt transmission. The second highest contributor group was the 30 percent of the PWID population who are diagnosed and not on ART; they are contributing an estimated 30 percent of new infections. This points to the need for increased HIV diagnosis as well as retention

NOTE: ART = antiretroviral therapy; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; MSM-IDU = men who have sex with men and who inject drugs.

SOURCES: As presented by Natasha Martin at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 12, 2018; adapted from Skarbinski et al., 2015.

in care, she said, but also suggests that New York City may have fewer individuals who are diagnosed and diagnosis rates that are lower than the national average. New York City may want to focus first on that population, she added. The two studies came to slightly different conclusions, which bolsters the importance of setting-specific responses. “A national picture is helpful, but a regional and local picture is really key when we’re thinking about how we plan our response,” she said.

Combination Prevention Maximizes Impact Cost-Effectively

Martin described another study that modeled HIV incidence among PWID in New York City in 2040 (Marshall et al., 2014). With no scale up of interventions, the model predicts an incidence of 2.13 PWID per 100 person-years. The model predicted that scaling up individual interventions would yield the following reductions in HIV incidence rates: increasing HIV testing (1.87); improving substance abuse treatment (1.57); increasing NSP coverage (1.40); and scaling up treatment as prevention (1.17). However, the maximum effect in reducing HIV incidence among PWID was derived from a combination prevention strategy that combines harm reduction with treatments. Cost-effectiveness analysis feeds into decisions about how to allocate limited resources in the prevention portfolio, noted Martin, and highlights the role of harm reduction as the backbone of infectious disease responses. A recent study examined the cost-effectiveness of HIV prevention portfolios in the United States, demonstrating the cost-effectiveness of a combination prevention portfolio (Bernard et al., 2017). In terms of priority, the study indicated that the first intervention implemented in the combination should be to scale up OAT to low, medium, and then high coverage. The next step should be to scale up NSPs, and then scale up HIV testing and treatment. The study also indicated that PrEP to prevent HIV in PWID is likely not cost-effective, she added.

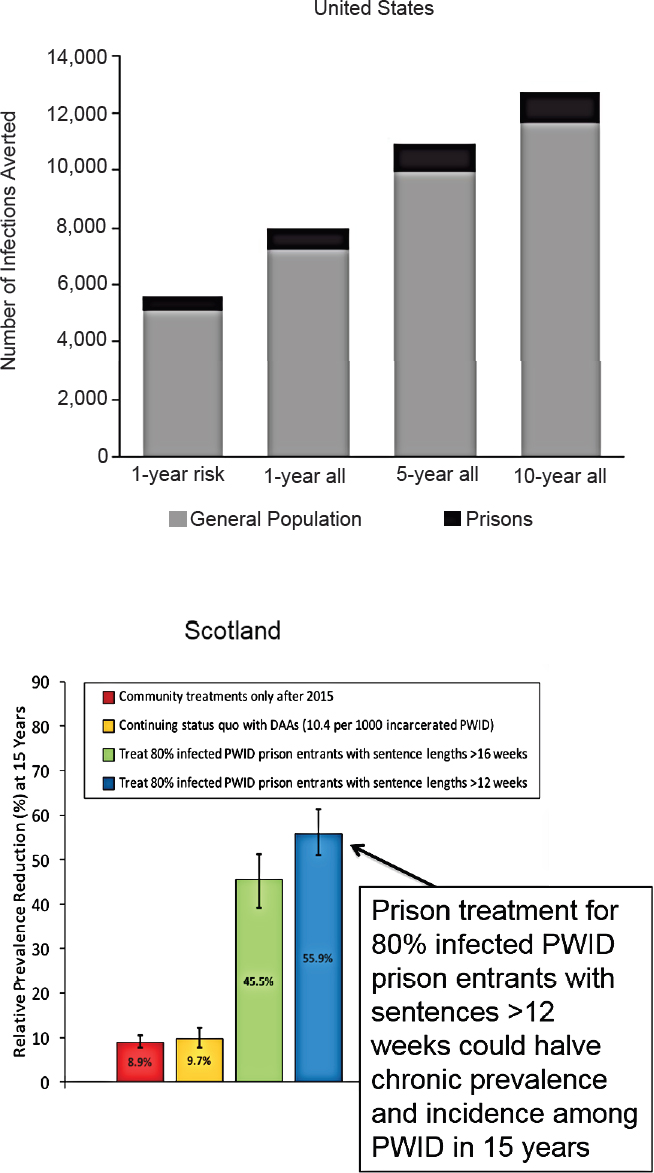

Exploring Challenges and Opportunities Among Incarcerated People Who Inject Drugs

Martin explained that there are high burdens of PWID in prisons who experience high rates of infectious diseases; prison appears to increase their risk of transmission of these diseases. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that compared to nonrecent incarceration, recent incarceration significantly increases the risk of acquiring HIV by an estimated 81 percent and increases the risk of acquiring HCV by an estimated 62 percent among PWID (Stone et al., 2017). This risk appears to persist after release, she added. However, reforming drug laws to be more ori-

ented toward public health could help to reduce HIV among PWID, said Martin. To illustrate, she described a case study from Mexico. In 2009, Mexico decriminalized possession of select drugs for personal consumption and mandated drug treatments at third apprehension. But to date, the limited knowledge of this public-health-oriented drug law reform has hampered its implementation and thus it has resulted in little effect among PWID in Tijuana, Mexico (Arredondo et al., 2017). However, based on the small effect observed in reductions of syringe confiscations, modeling has estimated that even this small change in policing could avert 5 percent of new HIV infections among PWID in Tijuana between 2018 and 2030. She reported that if the reforms were implemented properly—that is, if no syringes were confiscated and OAT were provided instead of incarceration for 80 percent of PWID—then these changes could avert 21 percent of new HIV infections among PWID in Tijuana between 2018 and 2030.

Prison also provides an excellent access point to engage people both in treatment and in harm reduction, Martin said, and researchers are now looking at the community benefits of treatment and harm reduction in prisons. Another case study in Mexico estimates that providing ART to PWID while they are in prison and upon their release could avert 12 percent of new HIV infections between 2018 and 2030 (Borquez et al., in preparation). The modeling suggests that during the same period, OAT could have a similar effect if provided in prison and on release (around 13 percent) and that combined ART and OAT could avert 18 percent of new HIV infections among PWID in the community. Martin said that HCV screening and treatment in prisons also have the potential to substantially avert new HCV infections in prisons and in the community, as well as reducing the incidence of HCV among PWID (see Figure 2-8).

Potential Ways Forward

Martin emphasized the urgent need to tackle HCV and HIV epidemics among PWID, especially in outbreak settings. Modeling indicates that the lack of harm reduction, coupled with restrictions on HCV therapy, may result in a very high HCV burden among PWID in some settings. She also highlighted the need to scale up combination harm reduction as well as HIV and HCV screening and treatment for prevention. The treatment rates required to control the epidemics are achievable (<100 per 1,000 PWID per year) and could eliminate HCV by 2030, but doing so will also require re-treatment of HCV reinfections without stigma and without the imposition of insurance restrictions. Public health–oriented drug law reform could promote positive change in preventing the risk of infectious diseases associated with incarceration among PWID; incarcera-

tion can also serve as an access point to provide harm reduction and treatment. Finally, she reiterated the importance of setting-specific approaches that are tailored to local epidemiology. While national-level pictures are helpful, the epidemics among PWID are highly heterogeneous and one setting’s requirements may differ substantially from the level of intervention required in another setting. Refining these models, she suggested, will require better epidemiological data for forecasting epidemics and assessing the interventions required. Modeling can also be employed to examine differences in epidemics and in the differential effect of interventions among subpopulations—such as gender, race, ethnicity, and so forth. She advised that future work should examine both the effect and the economic consequences of drug policy changes on infectious disease risk and transmission among PWID.

Discussion

Jay Butler, chief medical officer at the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, described using sofosbuvir to treat a patient with HCV genotype 1 who would cycle between actively injecting drugs and long-term abstinence. The patient achieved sustained virologic response but was reinfected with genotype 4 after a relapse. Given the public health impact of treatment and the effects of sustained virologic response on community transmission, Butler asked if modeling has factored in evidence that there may be lower risks or higher rates of spontaneous clearance among people who are reinfected. Martin replied that the majority of existing models do not currently incorporate any kind of effect that treatment may have on an individual’s posttreatment injecting risk. Current models conservatively assume no change in behavior after HCV treatment and that an individual’s risk of reinfection is similar to their risk of primary infection as a legacy of the time when the effect of treatment on injecting behavior, spontaneous clearance rates, and immunity were unknown. However, evidence suggests that in many settings, engaging

NOTE: DAA = direct-acting antiviral; PWID = people who inject drugs.

SOURCES: As presented by Natasha Martin at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 12, 2018; top figure from He et al., 2016; bottom figure adapted from Stone et al., 2017.

with health care providers may provide a catalyst for a person to find housing and employment, for example, which can have a positive effect on the individual’s injecting drug use trajectory. She said that models will be refined as more data emerge on the effect of HCV treatment on posttreatment risk behavior, spontaneous clearance rates, and reinfection rates. The effect of HCV treatment as prevention may be greater than expected, she added.

del Rio suggested that modeling could incorporate the effect of the different interventions that she proposed in states that have expanded Medicaid versus those that have not, given that Medicaid pays for many of the treatments and that ensuring access to health care for PWID is a critical component in stopping this epidemic. Martin commented that availability of treatment does not guarantee uptake. In the United Kingdom, for example, the nationalized health care system has provided free and widely available HCV treatment for PWID for a decade, but the uptake has been poor. The advent of the new treatments has inspired enthusiasm among PWID to request treatment, and there is less stigma from providers. Martin said it is important to monitor policies as well as the actual treatment uptake rates to identify barriers to treatment beyond the provider level. Most models indicate that there will be no effect on the epidemic without scale up of treatment, given the extremely low treatment rates among PWID historically and in recent years.

ECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS OF TREATMENT PROGRAMS

Benjamin Linas provided a health-economic perspective on the implications of treatment programs, exploring strategies for setting value-driven priorities to address the opioid epidemic and its infectious disease consequences. To provide a slightly different perspective on the epidemic, he presented data on BlueCross BlueShield plans among commercially insured individuals in the United States, showing the increase in the prevalence rate of opioid disorder over time. The rate spiked from 2.8 per 1,000 members in 2015 to 8.3 per 1,000 members in 2016,7 said Linas, which suggests an epidemic of opioid use disorder growing even in that pool of largely employed, commercially insured people. His presentation focused on the numerous viral and bacterial sequelae of the opioid use epidemic and injection drug use: HCV, HIV, endocarditis and bloodstream infections, skin and soft tissue infections, and osteomyelitis. He noted that much research has focused on the viral sequelae, but it is becoming clear

___________________

7 The figure is available at https://www.bcbs.com/the-health-of-america/reports/americas-opioid-epidemic-and-its-effect-on-the-nations-commercially-insured (accessed April 12, 2018).

that the growing bacterial consequences are probably underresearched and underdiscussed.

Overview of Cost-Effectiveness

Turning to the concept of economic value, Linas maintained that maximizing the effect of every available dollar is critically important because resources are always limited, and when addressing substance use there is often little political will to expand the resource pool. He defined cost-effectiveness research as the branch of decision science and health economics that seeks “value.” He said that contrary to popular opinion, the goal of cost-effectiveness research is not to save money. The goal is the same as the goal of all public health research: to spend as much money as possible, but to use it well to maximize population-level outcomes and “bang for the buck.” To set the stage, Linas provided a brief overview of one of the fundamentals of cost-effectiveness analysis, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) (see Box 2-2).

Another fundamental concept in cost-effectiveness analysis is the willingness-to-pay threshold. ICERs are calculated for various health care interventions to determine how much they cost on a per-quality-gained basis. However, it is unclear what the willingness-to-pay threshold should be. Sometimes analysts set the cost-effectiveness willingness-to-pay threshold at around $50,000 per quality gained, but many use $100,000

per quality gained. Linas noted that many interventions have an ICER of greater than $50,000. He added that the term “willingness to pay” is a misnomer that has become a problem for cost-effectiveness research. The question is not about how much we are willing to pay, he said, but about the opportunity cost: that is, whether money already being spent to maintain the status quo of the health system should be used in a new way. He explained

Anything that we can do with our money that would get us better outcomes than we are getting now for the same money is something we should move to. The willingness-to-pay threshold is really meant to be an estimate of, on average, what we get for a dollar in the U.S. health care system. It is not about a moral judgment about how much we are willing to pay or how much your life is worth.

He emphasized that cost-effectiveness maximizes population-level benefits of medical therapies, and although it does not seek to minimize cost, it does require explicit decisions about opportunity costs and the bang for the buck in the current health care system, which sometimes make people uncomfortable.

Finding Value in Addressing Hepatitis C Virus

Summary: Health Economics of HCV

HCV is the most common chronic infectious sequela of injection drug use, but despite that fact there has been robust national debate about the high cost of HCV treatment and the proper approach to HCV in PWID. However, the cost-effectiveness of HCV treatment is well established from a health economics perspective, said Linas. Routine testing for HCV and HCV treatment are both high-value interventions. Eliminating HCV transmission will require treating persons who inject drugs, he added. Testing and routine treatment for HCV are high-value interventions that provide rare opportunity for a cure.

HCV Testing

Since 2012, both CDC and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force have both recommended routine, one-time HCV testing for all adults born from 1945 to 1965, coupled with targeted testing for high-risk people born after 1965. These recommendations were based on a cost-effectiveness study indicating that the prevalence of HCV in the baby boomer cohort (born from 1945 to 1965) is so high that trying to target test to that group misses too many cases, so expanding and routinely offering testing to that group

provides great value, Linas said. However, the scenario has changed since 2012, with CDC incidence data on HCV indicating there are steeply increasing incidence rates between 2010 and 2015 among the groups of people age 20 to 29 and age 30 to 39, neither of which are currently recommended for routine testing. New literature is emerging that is documenting the cost-effectiveness of testing in various settings, which are finding that it would be cost-effective to expand the recommendation for routine one-time testing for HCV to all adults in the United States, similar to HIV recommendations (Barocas et al., 2018). Linas said the finding is so robust that it is difficult to find venues and situations in which it is not a cost-effective opportunity to screen for HCV routinely. It is cost-effective and provides good value in venues where the prevalence is high, but also when the prevalence is similar to the general population prevalence, when linkage rates to care are low, even when treatment prices are high, and even when the risk of reinfection is high (Assoumou et al., 2018; Schackman et al., 2015, 2018).

HCV Treatment

Multiple effective antiviral drugs for HCV are available, said Linas, including five currently preferred regimens for genotype 1A infection and four alternative regimens, all of which are all-oral regimens with cure rates approaching 100 percent. Research is emerging around the cost-effectiveness of the new HCV therapies, indicating unanimously that they are robustly cost-effective in every genotype, with shorter treatment regimens, in injection drug users and other analyses (Leidner et al., 2015; Linas et al., 2015; Martin et al., 2012; Morgan et al., 2018; Rein et al., 2015; Younossi et al., 2017). Despite the demonstrated cost-effectiveness of the therapies, treatment costs are restricting access because of payor restrictions based on disease stage and drug use. Linas attributed this to the misconception that cost-effectiveness is equivalent to affordability.

Decisions around running an insurance plan require a fundamentally different approach to cost-effectiveness or value-based research. In the context of value, the central question in cost-effectiveness is how to get the best possible outcomes given the resources currently available. In running a health care plan, the central question is very different: “If we treat all HCV-infected people in our plan, how much will we spend this year?” Linas noted that HCV drug costs have decreased substantially in the United States with respect to the catalog price—although the drug market actually operates on lower negotiated prices—but the “sticker” price of curing HCV has declined to around $20,000 to $30,000 for most people in the United States, which is not necessarily good or fair, but it is much lower than the persistent image of HCV medication as a bottle full of “diamonds” costing $1,000 per day. When decision makers and payors

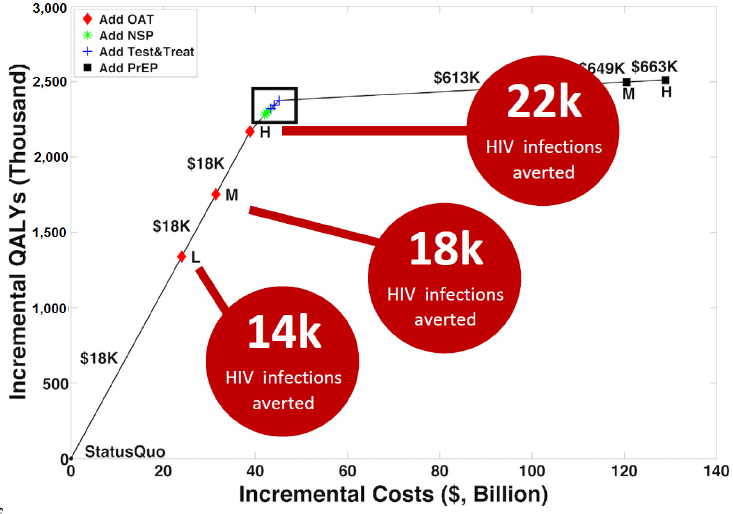

NOTES: L, M, and H refer to low, medium, and high coverage. HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; NSP = needle services program; OAT = opiate agonist therapy; PrEP = preexposure prophylaxis; QALY = quality adjusted life-years.

SOURCES: As presented by Benjamin Linas at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 12, 2018; adapted from Bernard et al., 2017.

make decisions about what to cover or not based on false information, he warned, they make bad policy.

Finding Value in Addressing HIV

HIV is probably the best studied and best resourced viral infection affecting injection drug users, said Linas. It is also a field that has embraced cost-effectiveness research, likely because a lot of people working in HIV are outside the United States and in resource-limited settings. He presented Figure 2-9 to illustrate the “efficiency frontier” of HIV prevention packages, which visually represents an ICER (Bernard et al., 2017). Each of the points on the graph represents a type of HIV prevention package for persons who inject drugs, with red diamonds representing OAT, also known as medications for opioid use disorder (MOUDs). Green stars represent adding more NSPs, blue crosses represent adding test-and-treat for

HIV for the injection drug users, and black squares represent PrEP. The vertical axis is denominated in terms of quality-adjusted life years lived by the cohort, and the horizontal axis is the incremental cost expressed in billions of dollars. The slope of the line that connects any two points on this graph represents how much benefit will be obtained (the rise) over how much cost (the run). The steeper this line is, the more value is gained from the intervention; flat parts of the curve represent spending more money but not getting as much benefit. In the figure, the steepest part of the curve goes from the status quo to all levels of more MOUDs and PrEP is at the far right of the curve. That is, if the goal is to prevent HIV infection, and only one intervention is possible, then it should probably be more MOUDs. Depending on the level of implementation, MOUDs are estimated to avert between 14,000 and 22,000 HIV infections. “MOUDs are HIV prevention the same way that PrEP is HIV prevention, perhaps even more so than PrEP is HIV prevention,” he said, and urged decision makers around priorities for HIV research to prioritize MOUDs as highly as PrEP.

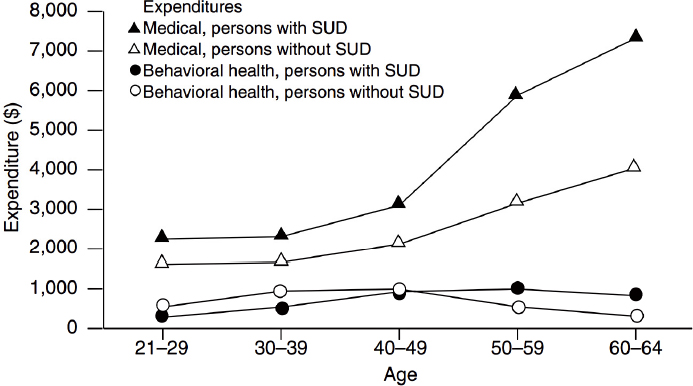

NOTE: SUD = substance use disorder.

SOURCES: As presented by Benjamin Linas at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 12, 2018; Clark et al., 2009.

Finding Value in Addressing Endocarditis and Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

Linas shifted to finding value in addressing endocarditis and skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs). A national inpatient sample examined the burden of hospitalization for endocarditis in the United States, which is increasing among the youngest age group (15–34 years) of injection drug users to the extent that it overwhelms the decrease in admissions among the older age groups (≥35 years) (Wurcel et al., 2016). Similar data from North Carolina demonstrate that the burdens of endocarditis and SSTIs are becoming more costly, he added. Between 2010 and 2015, the burden of endocarditis related to drug use increased 1,800 percent or 18-fold in 5 years. However, there is little existing evidence to inform cost-effective interventions around substance use and the effect on endocarditis and SSTI.

Expenditures for Patients with Substance Use Disorder

Linas concluded by noting the continuing transition into an era of the accountable care organization (ACO), which provides capitated payments based on the number of patients covered and (theoretically) aligns its financial incentives with quality of care. Data on medical expenditures and behavioral health expenditures for patients who have a substance use disorder (SUD) indicate that among every age group, the people with SUDs cost more (Clark et al., 2009) (see Figure 2-10). Studies also show that these patients often have worse outcomes, as well. However, he warned against ACOs being construed as a panacea for SUDs. Anecdotally, he has heard providers express some concerns about the effect on the ACO if these patients both cost more and have worse outcomes. Even if ACOs are explicitly forbidden from excluding people because of their substance use, there are myriad ways to indirectly exclude them. He was hopeful that ACOs will align their incentives with quality care for SUDs, because better outcomes for people with SUDs may lower costs in the long term.

PERSPECTIVES OF PATIENTS AND PROVIDERS

A provider’s perspective on the infectious disease consequences of the opioid epidemic was shared by Seun Falade-Nwulia, who was the past medical director of the Baltimore City Health Department HIV Early Intervention Initiative program, which provides HIV and HCV care in the public health clinics. She is currently an assistant professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and drew on her range of experiences working on the inpatient service,

seeing patients in an infectious disease clinic, and working in the community. A large proportion of cases she sees on the infectious diseases consult service are patients with injection-related infections such as septic arthritis, osteomyelitis of the spine, endocarditis, and cellulitis.

Falade-Nwulia is frequently consulted on patients who inject drugs who have been readmitted to the inpatient service for these infections that have progressed despite previous discharge to a facility on an appropriate course of prolonged (e.g., 6 weeks) of intravenous antibiotics. Invariably, these patients often relapse into drug use after taking only a couple of weeks of their antibiotics, are discharged from the facility, and then represent to the hospital with progression of their infection. As an infectious disease specialist, this poses a difficult situation—a longer duration of antibiotics would generally be recommended, but she knows it is likely that the treatment will not succeed as patients who do not also receive addiction care will often relapse into drug use prior to completing the prescribed course of antibiotics. This underscores the need to provide addiction care for patients wherever they access health care. Health systems need to be able to respond to patients with opioid use disorders who have true pain that needs to be addressed but who also need to complete prolonged (e.g., 6 weeks) of therapy, she explained. For example, the system should have programs that include rapid start of buprenorphine in the inpatient setting and potentially, linkage to methadone programs, so that patients can successfully complete their prescribed therapies at the patient rehabilitation facilities where they are sent to complete these antibiotics.

In her work in outpatient settings, Falade-Nwulia often sees new cases of HBV, HCV, and HIV that could have been prevented. She maintained that comprehensive programs must be able to engage PWID at whatever point they enter the health care system—be it in the ED, the inpatient setting, or the community fair. These patients need to be screened and provided with the appropriate follow-up even if they do not have current infections. Patients without HBV need to be vaccinated; patients without HIV should be considered for PrEP; patients without HCV should receive counseling on HCV risks and prevention.

Falade-Nwulia noted that her program tries to lower the barrier to care by providing linkages to treatment for hepatitis for patients in the ED, so that patients who have HCV are automatically referred to the viral hepatitis clinic. However, she recounted a sad situation involving a patient in her program whose insurance did not approve coverage of HCV therapy caused by a low stage of liver fibrosis. The clinical team was able to get her free HCV care through a patient assistance program, but she fell out of care because she could not wait the 6 to 8 months it can take to access those programs. She re-presented to the ED and was

pregnant, with her baby at risk of perinatal transmission of HCV. Falade-Nwulia observed,

There’s nothing sadder for me than for a patient [with HCV] who has overcome the fear of the stigma they are going to receive in the health care system . . . and actually made it to my clinic, and I have to say to them “I have treatments that are simple and can guarantee you a cure of your hepatitis C infection. But guess what? I cannot get you the drug, because I practice in Maryland where we have restrictions on access to hepatitis C treatment—if you have stage F1 or lower liver disease, [and you are insured by Medicaid] you cannot access HCV treatment.”