3

Exploring Opportunities for, and Barriers to, Treatment and Prevention in Public Health, Hospitals, and Rural America

This chapter comprises presentations and discussions about setting-specific opportunities for, and barriers to treatment and prevention in public health, hospitals, and rural America. Matthew La Rocco, community liaison with the Louisville Metro Syringe Exchange Program in Kentucky, described the establishment of harm reduction programs in his community and some of the specific challenges faced by women who use drugs in accessing treatment. Katie Burk, viral hepatitis coordinator at the San Francisco Department of Public Health, provided an overview of hepatitis C virus interventions in her city. Honora Englander, associate professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) School of Medicine, described opportunities for improving care for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder (SUD). Challenges and opportunities in delivering care in rural areas of the United States were explored by Nickolas Zaller, associate professor of public health and director of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Office of Global Health.

ROLE OF PUBLIC HEALTH DEPARTMENTS

Harm Reduction Programs

Matthew La Rocco, community liaison with the Louisville Metro Syringe Exchange Program in Kentucky, explored the role of harm reduction in reducing the transmission of infectious diseases. He drew on his experience as a certified drug and alcohol counselor who is also in long-

term recovery for drugs and alcohol. He explained that syringe services programs (SSP) is the preferred terminology over needle exchange or syringe exchange, because it more accurately reflects the multiple services, other than needle exchange, that these programs provide. He also noted that people who inject drugs (PWID) and people who use drugs (PWUD) are preferred terminology because they are people-first language, and a word like addict can be very stigmatizing in its focus on just one element of an individual’s life—one that often carries a great deal of shame with it owing to societal constructs around drug use. “We ought to talk about people who use drugs as people first . . . their drug use is a part of their life, but isn’t the defining characteristic,” he said.

Political Boons and Barriers to Syringe Services Programs in Kentucky

Kentucky Senate Bill 192 was introduced on February 13, 2015, representing a momentous state-level response to the opioid epidemic with respect to both syringe exchange and treatment funding, said La Rocco. On February 25, the health department in nearby Scott County, Indiana, announced that within the past 2 months, they had confirmation of 26 new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) diagnoses and four preliminary positives. A month later, Scott County’s health department reported 55 newly diagnosed cases and 13 preliminary positives and opened an SSP 2 weeks later, by which time there were 84 newly diagnosed cases and 5 preliminary positives. By May 19 of that year, the numbers had snowballed to 157 diagnosed cases and one preliminary positive. Senate Bill 192 had been signed by the governor of Kentucky on March 25, La Rocco explained, not because the state was exceptionally forward thinking and progressive; the driving force for passing the bill was the HIV epidemic exploding just over the state line. He explained that Senate Bill 192 allows health departments to operate SSPs, but it requires the approval of the local board of health—which has not been an issue in most counties trying to start a program—as well as the approval of the city’s or county’s legislative body (e.g., a city council or board of magistrates). As a result of the latter stipulation, stigmatic thinking around drug use and misperceptions about SSPs have impeded the development and the effectiveness of SSPs across the state. For example, in some high-risk counties identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as being at risk for hepatitis C virus (HCV) outbreaks, SSPs are open for only several hours on only 1 day per week and cannot effectively mitigate or stop the spread of infectious diseases.

La Rocco observed that although they did not encounter significant political barriers to the start of SSPs in Kentucky, they did face significant political barriers that hamper the use of evidence-based best prac-

tices models to most effectively reduce the transmission of HIV, HCV, infectious endocarditis, staph, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), cellulitis, soft tissue infections, and so on. Louisville opened the first SSP in Kentucky on June 10, 2015, he said. The program opened with a needs-based negotiation model in a single fixed site at the health department, but then quickly partnered with Volunteers of America Mid-States for additional community sites. The initial needs-based model allowed PWID to bring any number of syringes into the SSP and they would receive a full week’s worth of syringes in return, regardless of the number they brought in or brought back. The program received pushback at the state level because of the exchange rates, and by 2015 Republican representatives began lobbying for a one-to-one exchange, ostensibly because of concerns about the risk of needle sticks in the community and resultant HIV and HCV exposure, which La Rocco said are unfounded (see Box 3-1).

Kentucky’s attorney general responded to the pressure and provided a formal opinion supporting SSPs and their autonomy in choosing their own operating models. Democrats introduced House Bill 160 to lay out the specifics of needle disposal by health departments, with no reference

to needle exchange rates, but the bill was amended by the Republican senate to mandate a one-for-one exchange and then ultimately died when it went back to the House.

Local Challenges in Louisville

La Rocco surveyed some of the local challenges that they have faced in Louisville. The city and county have merged into a very large area of almost 400 square miles. The health department is working to address drug use across the county, but there is a pervasive perception that drug use is limited to the West End of the city where poverty is more widespread. In the East End of the city, denial of the reality of drug use and “not in my backyard” attitudes abound. The reality, he said, is that drug use happens across the city and everyone is susceptible to addiction—rich, poor, young, old, black, and white. These misperceptions around the geography of PWUD and PWID in Louisville have created barriers to establishing treatment centers, residential programs, halfway houses, SSPs, and other opportunities for people to engage in treatment where they live.

Barriers to Treatment

Many PWID and PWUD have had negative experiences with medical providers, leading to reduced engagement with preventive and ambulatory care, said La Rocco. He recounted the story of a patient who had the incredibly painful experience of having an abscess lanced, drained, and packed without any kind of general anesthetic or numbing. These types of experiences can engender serious distrust of the medical system and leave PWID hugely disincentivized to seek treatment of any kind until their condition is very severe. These delays in diagnosis and treatment for conditions such as abscesses and endocarditis significantly increase the cost of treating the patients. It also compounds the impact that these infectious diseases have on the individuals and their quality of life. For example, if they require surgery that could have been avoided by earlier treatment. He added that this aversion to seeking treatment also leads to missed opportunities for infectious disease screening and treatment that are provided when a person seeks medical care from a primary care physician or in the emergency department (ED) for some other reason.

Maintaining a Low Threshold

La Rocco explained that in Louisville’s SSP, they try to maintain a very low threshold for services. This means that rather than pressuring people to be screened for HIV and HCV—thus raising the threshold for services—they try to be very careful in the language they use with people. Strongly encouraging HIV testing, for example, creates an intractable power dynamic with people who engage with the SSP, most of whom are expecting to be treated poorly and are surprised when they are not. When program staff ask a PWID or PWUD to be tested, it communicates implicitly that the staff member really wants the person to be tested, and will be disappointed or unhappy if the person chooses not to. This can discourage people from coming to the SSP. At his SSP, they address this by asking their staff to use very intentional language to raise awareness of testing services and the benefits of testing, but without raising the threshold. They might remark that people like to know their HIV and HCV status just because it gives them better information and enables them to make better choices for their health, for example:

If you would like a test today, we can get you tested. If you go, man, I’m good, but maybe something happens in the next week or two weeks or few months, maybe you share a syringe, have unprotected sex, a risk factor pops up, and you go, “Man, I really need to get tested.” Whenever you are ready to test, you just come in here and we will get you tested. If you are positive, we can get you referred for services.

La Rocco explained that this puts the ball back in the person’s court, but with the subtlety that at some point, the person will be ready to test. However, it does not put pressure on them to test and does not raise the threshold for services.

Challenges Faced by Women Who Use Drugs

La Rocco cautioned that women who use drugs (WWUD) and women who inject drugs (WWID) tend to face higher levels of stigma than men do. Drug-related stigma and internalized shame put these women at significant risk for contracting infectious diseases and delaying treatment for those diseases. A key challenge, he said, is that these women are less likely to access annual reproductive health care, which provides opportunities for infectious disease screening, education, and referral for treatment as needed. Pregnant women and women with children often face more stigma than their male counterparts. Because of unfair cultural pressures and expectations placed on mothers, WWID and WWUD can experience a significant amount of self-shaming as well as shaming from

others. Internally, they tend to self-shame because of what, ultimately, is an unfair cultural expectation for them, he added. These women become less likely to seek treatment and more likely to delay treatment for soft tissue infections, sexually transmitted infections, septicemia, and endocarditis. Often, they resist going to the hospital because of fears that child protective services will become involved and they will lose custody of their children, or fears that people will treat them poorly for being a mother who uses drugs.

Intimate partner violence is another critical issue for WWUD and WWID, said La Rocco. Women who experience intimate partner violence are often not in control of the drug supply or the rituals surrounding drug use, including access to safe syringes or other equipment. “They don’t often get to determine when they use drugs, how much they use, who they are using with, or what equipment they are using,” he explained. This lack of control places them at higher risk for acquiring an infectious disease. Furthermore, women who are experiencing intimate partner violence might not be allowed to go to an SSP, or their partner might come to the SSP but fail to share the information about safe practices and disease prevention. Other women experiencing intimate partner violence may come into the SSP, but are accompanied by their partner, which can limit their level of honesty around their drug use or what is happening in their home. Housing services for women who experience intimate partner violence may also exclude WWUD from engaging in services. La Rocco said that this may be too much to ask of someone who has an SUD and is dealing with significant past and current trauma but who is ready to leave the domestic situation that is preventing them from being healthy and more functional. Women who cannot access services or escape their domestic situation can end up feeling hopeless, he explained, which has the potential to increase their drug use and thus their risk of infectious diseases.

Women in relationships are often tasked with the domestic responsibilities as well as the responsibilities for acquiring drugs, earning money to buy drugs, and getting a better deal on drugs, noted La Rocco. This can leave them with less time to access services where they can be educated about preventing infectious diseases, screened, and referred for treatment. Additionally, WWUD, especially those with felony records, have far more difficulty securing well-paying jobs than their male counterparts. This puts those women at higher risk for engaging in sex work in exchange for money or drugs, placing them at higher risk for HIV and sexually transmitted infections. He suggested that female condoms give women more power over the use of condoms because they are not dependent on the man’s cooperation, but the high cost of female condoms relative to male condoms limits an SSP’s ability to provide them in the same quantity.

Developing Partnerships

La Rocco said that in Louisville they are actively looking to develop partnerships to better help people engage in infectious diseases treatment by mitigating some of the consequences and risks associated with injection drug use, both for the community that uses drugs and then the community that engages them. La Rocco and the Louisville Metro Syringe Exchange Program have a relationship with the Kentucky Care Coordination Program to connect people living with HIV to care coordination providers located very near the SSP, as well as relationships with nearby local hospitals that are working to treat HCV. Additionally, they are exploring a partnership with physicians at the University of Louisville Hospital to increase early treatment of soft tissue infections and endocarditis to help reduce the number of ED visits, among other benefits. The partnership would ensure that people who are concerned they have an infection related to their injection drug use have access to trained, polite, and respectful physicians. This would benefit PWID because it reduces the risks associated with delaying treatment, he said, and it would benefit physicians because it allows for early diagnosis. It would also reduce congestion in EDs, which benefits hospitals, and reduce costs for Medicaid payors when more patients can be treated with oral antibiotics at earlier stages of infection.

Discussion

Brian Edlin, chief medical officer of the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention at CDC, asked if there are PWUD who also care about their health enough to engage in treatment for their HCV without first receiving addiction treatment. La Rocco maintained that most people dealing with an SUD are concerned about their health (including himself when he was actively using) and the presumption otherwise is yet another stigma faced by PWUD. Having an issue with addiction does not disqualify somebody from caring about their health, just as it would be unfair to say that people who are overweight or have high blood pressure cannot care about their health. The simple fact that a PWUD has come to a syringe exchange to get sterile syringes, bandages, antibiotic ointment, and alcohol swabs—facing potential stigma or being seen by police—suggests that the person is very concerned about their health. The blanket recommendation that addiction must be dealt with first does not take into account the different ways that addiction can affect people, La Rocco argued. People with SUDs have different levels of functionality. Some would never be suspected of dealing with the disorder because they have so-called recovery capital: they have jobs, financial means, education, supportive family members, and so forth. There is no

reason that they could not engage in and effectively complete services, said La Rocco, even in the midst of their continued drug use. Many people are not fortunate enough to have that level of capital, however, and may be homeless or dependent on shelters and food pantries. These people may need a higher level of support and services, including the provision of treatment services through services they are already attending regularly (such as shelters). Studies have shown that if they are engaged in SSP-type services, people who are actively using during HCV treatment do not have a higher risk of reinfection than the non-drug-using community, he added.

Carlos del Rio, professor of global health, epidemiology, and medicine at Emory University, asked how health departments could better link up with local-level organizations—such as SSPs—that provide services that the health departments are unable to provide because of legislation or financing. La Rocco remarked that public health is inclusive of mental health as well as physical health, which are inextricably linked. In situations where the political climate or legislative barriers preclude the public health department from establishing SSPs, he said, the department should be a champion for drug treatment programs and other programs that reach out to PWUD and provide low threshold access to wraparound services. Health departments can assist programs applying for grants, for example, by writing letters of support or offering the services of a grant writer. Health departments cannot always deliver programming, La Rocco said, but they can certainly support and work collaboratively with smaller agencies.

Overdose, Hepatitis C Virus, and Drug User Health

Katie Burk described the response of the San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH) to the overlapping public health crises of overdose, HCV, and drug users’ health. She reflected that the recent focus on dramatic increases in overdoses and HCV rates in rural areas—for good reason—has created a narrative that somewhat obscures the story of cities like San Francisco that have always been affected by high rates of substance use, HCV, and overdoses. She reported that San Francisco has an estimated 22,500 active PWID (Chen et al., 2016). An estimated 22,000 people are HCV seropositive, among whom around 12,000 people are believed to be viremic (Facente et al., 2018). Around 16,000 people in the city are living with HIV, of which about 6 percent are PWID and 15 percent are men who have sex with men and PWID (SFDPH, 2017). San Francisco has the highest rate of liver cancer in the United States, she said, which is driven by high HBV and HCV rates.

Intertwined epidemics require integrated responses, Burk main-

tained. SFDPH is implementing comprehensive prevention programs that can provide people with all the services they need, “no matter what sort of door they are walking in.” She noted that many PWID experience multiple health consequences—overdose, HCV, and HIV—that are often related to the same or overlapping risk factors. For example, many people are not currently engaged in primary care. If they are engaged in syringe exchange programs they should, if needed, be able to receive HCV treatment and/or be induced to begin methadone or buprenorphine treatment in that setting. She cited two examples of these types of integrated care models. The 6th Street Harm Reduction Center, a program of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, is a harm reduction drop-in center that provides syringe access services and naloxone. They have added HCV education and group treatment interventions, as well as buprenorphine initiation services. The county jail also provides testing for HIV, HCV, and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). PWID can start methadone or buprenorphine while in jail and then continue their treatment when they are released; HCV treatment programs have also recently been implemented.

Drug User Health Initiative

SFDPH has an internal working group called the Drug User Health Initiative (DUHI), said Burk, focused on addressing the needs of PWUD in San Francisco with integrated programs. DUHI’s mission is to support drug users in caring for themselves and their communities through strengthening and aligning services and systems promoting drug user health; its vision is a system of care and prevention that supports health equity for drug users and ensures that all people who use drugs are treated with dignity and respect throughout San Francisco. She said that a system where “any door is the right door,” for example, would allow people coming in for sexual health services also to receive opioid agonist therapy if needed. Burk outlined DUHI’s key five initiatives:

- overdose prevention, education, and naloxone distribution;

- syringe access and distribution;

- HIV/HCV prevention, screening, and treatment;

- alcoholism prevention; and

- a harm reduction workforce development.

Four essential components of DUHI’s drug user health infrastructure are syringe access and disposal, naloxone overdose education, low-threshold methadone and buprenorphine, and the End Hep C SF initiative. There are multiple models for opioid replacement therapy, including six

methadone programs that are equipped to allow people to start same-day treatment. To help address the barrier of primary care providers’ reluctance to induce people on buprenorphine, an Office-Based Buprenorphine Induction Clinic (OBIC) uses pharmacists to do the induction work. Once the person is stable, their prescriptions are transferred to their primary care clinics. She explained that this is part of a wider effort to provide lower threshold access for buprenorphine, which also includes a street medicine team providing low-threshold buprenorphine for homeless individuals. Burk explained that syringe access and disposal sites in San Francisco are another key component of SFDPH’s outreach and engagement with vulnerable San Franciscans. Services are provided 7 days per week and although sites are more concentrated in the downtown area, an extensive peer-run secondary exchange network expands program reach into the outer neighborhoods of San Francisco. Naloxone access is available at all sites, and HIV and HCV testing are available at most sites.

Response to Drug Overdoses: NOSE and DOPE

Turning to their overdose prevention work, Burk highlighted SFDPH’s two overarching strategies: SFDPH’s Naloxone prescription for Opioid Safety Evaluation (NOSE) project and the Drug Overdose Prevention and Education (DOPE) project, which is housed at the Harm Reduction Coalition, which is funded by SFDPH. Burk explained that the NOSE project was launched in response to the problem of opioid analgesic deaths in the city, which exceeded 100 each year between 2000 and 2012, and were continuing to persist despite significant reductions in heroin-related overdose deaths. They began a program in which providers were encouraged to coprescribe naloxone to any patient prescribed opioids long term in six primary care “safety net” clinics in the system that were highly affected by overdose. Analysis of the intervention found that prescribing naloxone to 29 patients averted one opioid-related ED visit in the following year (Coffin et al., 2016). Furthermore, the analysis found that in-clinic conversations with a patient about why naloxone was being co-prescribed was an important intervention in and of itself, because it helped the patients understand that opioids are potentially dangerous drugs.

Burk explained that the DOPE project has taught overdose prevention and response to drug users, their friends, their family members, and service providers since 2001. Since 2010, naloxone has been distributed under standing order from SFDPH to people most at risk of experiencing or witnessing an overdose; distribution occurs at 15 sites serving PWUD, including all of the SSP programs and sites. More than 9,000 people have been trained through the program, and there have been 4,000 reported reversals, including 1,247 in 2017 alone. Since 2004, the numbers of nal-

oxone enrollment, refills, and reversal reports to DOPE have all been increasing, with the trend escalating sharply since 2013. This illustrates that the number of lives saved is directly related to the amount of naloxone that is put into the hands of PWUD out in the community, she said, and it demonstrates that the most effective first responders to the overdose crisis are PWUD and their friends and families.

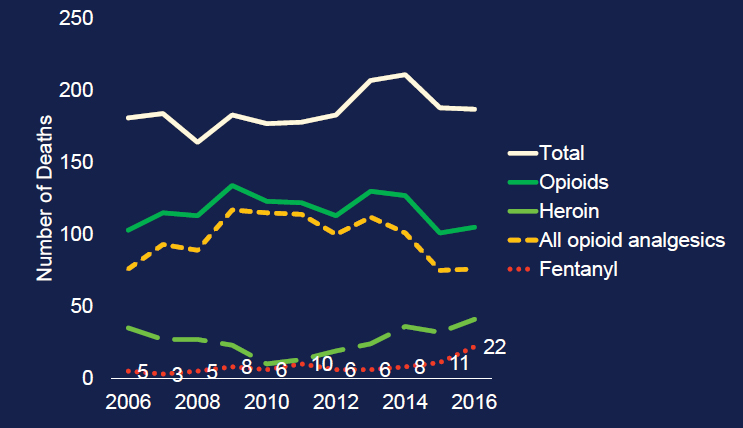

Burk said that together, the NOSE project and the DOPE project have managed to hold at bay the dramatic increases in overdose death rates ongoing in the rest of the country and in other parts of California—and have done so despite all indications that opioid use is continually rising in San Francisco. Although ED visits, hospital admissions, and treatment admissions related to opioid use have generally increased in San Francisco since 2006, the death rate has declined for the most part. Figure 3-1 illustrates the number of overdose deaths by opioid in San Francisco since 2006. She said that the DOPE project has been leading the charge to help the community adapt to the changes in the drug supply. Fentanyl-related overdose deaths can be prevented with the same tools employed to respond to a heroin-related overdose. However, deaths caused by fentanyl-related overdoses take much less time than heroin-related overdoses, so a quick response as well as efforts to avert an overdose in the first place are essential.

SOURCES: As presented by Katie Burk at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 12, 2018; Phillip Coffin, San Francisco Department of Public Health.

Hepatitis C Virus Elimination Initiative

Burk said that SFDPH has developed its HCV programming in ways that are integrated with its overdose programs and HIV programs. San Francisco’s drug user health infrastructure makes HCV elimination a feasible goal, said Burk, because SFDPH already provides good access to a suite of interventions around prevention, testing, linkage to care, and treatment access (relative to the rest of the country). However, planning for elimination will require coordinating responses and aligning existing work to appropriately scale up.

Burk described End Hep C SF, San Francisco’s HCV collective impact community-led elimination initiative, which was launched in 2015 with the vision of ending HCV as a public health threat and eliminating HCV-related health inequities. Its diffused leadership model relies on 32 community partner agencies engaging with each other such that their activities become mutually reinforcing. For example, if advocates successfully increase funding into the system to address HCV, then health departments can fund crucial HCV services. The staff of drug treatment programs and SSPs can in turn focus on outreach, education, testing, and linkage to providers for treatment and cure. People treated through the system can then become peer navigators who go out into the community to talk about the positive effect that HCV treatment has had on their lives, thereby inspiring new groups of people to seek HCV testing and curative treatment.

Hepatitis C Education and Prevention Campaign

At the initiative’s outset in 2015, focus groups were implemented with PWUD to understand their awareness of the new HCV treatments and how they would like to be talked to about the treatments. Three key messages emerged:

- “Sharing equipment spreads HCV. Come get sterile stuff.”

- “We can’t treat Hep C if we don’t know we have it.”

- “Living with Hep C? New treatments have changed the game.”

The messages were replicated through an education and prevention campaign delivered through social marketing under the primary message: “There is new hope for people with Hep C. . . . Come visit us to talk about the new cure.” Posters placed at agencies that provide HCV prevention, testing, and linkage services feature photographs of those agencies’ staff that reflect the demographics of the patients that use their programs.1

___________________

1 Resources are available for download at www.EndHepCSF.org (accessed April 11, 2018).

These messages served as an invitation for community members to ask about HCV services and curative HCV treatments.

Community-Based Hepatitis C Testing

End Hep C SF partners have worked hard to scale up rapid community-based HCV testing in community settings where the target population were already seeking services, said Burk. Community providers, supported by SFDPH, added HCV testing in settings where naloxone was being distributed and drug users were already successfully engaged in interventions: syringe access programs, homeless shelters, the county jail, single-room occupancy hotels, methadone programs, residential drug treatment programs, transgender wellness groups, and STD clinics. She reported that since the End Hep C initiative started in January 2016, there have been increases in the number of HCV tests while the 15 percent rate of reactive antibody tests has been maintained throughout the scaled-up testing. This demonstrates that SFDPH is using HCV rapid testing resources in high-prevalence settings and successfully engaging the highly affected populations, she added.

Treatment Access Strategies

When direct-acting antiviral treatment for HCV became available in 2014, Burk said, SFDPH realized that accessing the liver clinics was a barrier for many people, particularly marginalized populations, such as people who have been incarcerated, use drugs, have mental health issues, and/or are homeless. Burk explained that in 2015, demand was great at the primary care clinics with a high prevalence of HCV among their patient population. A pool of known HCV-infected patients had developed within the San Francisco Health Network, and liver clinic referrals were becoming a bottleneck for that population. Because the HCV treatments are so well tolerated, treatment in a specialty setting was no longer necessary for the majority of cases. To improve treatment access, SFDPH designed an initiative to train and empower primary care physicians to treat HCV themselves. Components of this capacity-building initiative for primary care physicians in the San Francisco Health Network include in-person training, electronic referral consultation services with experienced providers, and individualized clinical technical assistance with developing a workflow.2 Pre- and postintervention analysis found that the total number of patients treated increased by 112 percent and the total clinics

___________________

2 The San Francisco Health Network is a group of 12 primary care clinics under the umbrella of SFDPH.

represented among those treated increased by 140 percent (Facente et al., 2018). She said that primary care providers report that they enjoy treating their patients for HCV, because it is powerful for them to be able to tell patients that they are cured.

Having done this work to bring treatment into primary care, Burk said, SFDPH is now working to expand treatment outside of traditional clinical settings. Given the valid reasons why PWUD may not want to engage in traditional care systems, she said, SFDPH is trying to be creative in reaching them through other channels. To improve access to treatment outside of primary care, SFDPH is working to scale up smaller programs and pilots to treat HCV at the county jail, a syringe exchange, a gay men’s sexual health clinic, homeless shelters, through street medicine teams, and the opiate treatment outpatient program at the University of California, San Francisco. She said, “We are doing some incredible life-changing work with these populations by embodying the experience of harm reduction and meeting them where they are, literally.” Burk highlighted the national Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Hero study on patient-centered models of HCV care for PWID as evidence that this work can and does happen outside of San Francisco. This study is comparing patient navigation to directly observed therapy for this population in eight states. Thus far, 1,553 PWID have been screened, of which 50 percent (775) were eligible for treatment; nearly 500 PWID have now started treatment.3

Best Practices and Lessons Learned

Burk surveyed some best practices and lessons learned from the experience in San Francisco. She suggested that peer-driven program models are essential to reaching at-risk populations through programming organized around where the target population is already located. Achieving population-level reductions in overdose deaths requires naloxone saturation in the community in addition to educating people about how to prevent and respond immediately to an overdose. Different drug-using communities necessitate different interventions, she noted, which requires understanding and continually assessing local-level data and demographics as well as being nimble in response. For example, the DOPE project and SFDPH are now working to adjust their systems to the influx of fentanyl into the drug supply. Multidisciplinary teams are key to advancing agendas, she added. Potential starting points for interventions are community engagement, micro and macro policy changes, and leadership buy-in. She emphasized that it is critical to integrate HCV and HIV awareness activi-

___________________

3 Data source: Kimberly Page, University of New Mexico.

ties into opioid safety efforts, and vice versa. Viral hepatitis coordinators with very limited program funding are often advised to leverage existing infrastructures, such as HIV or injury prevention, she said, and suggested modeling this strategy in federal-level funding proposals.

Discussion

Dace Svikis, professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, asked how HCV programs in San Francisco are tailored to the unique needs of women. Burk said that one of the syringe exchange sites has a long-running and well-attended weekly ladies’ night, which includes dinner, and creates a safe, women-identified space for syringe exchange and overdose prevention work. Citywide, programs are responding to needs of their target populations by ensuring that programs delivering services are staffed by people who represent the demographics of the people they serve.

Referring back to Edlin’s question of whether some PWUD care about their health enough to engage in treatment for HCV prior to receiving addiction treatment, Burk remarked that part of the spirit of the End Hep C SF initiative is that it tries to be consumer and community led. Organizers who are designing initiatives are eager to have PWUD involved in leadership and meetings; they also create lower threshold engagement opportunities so the community has options for how to contribute to the initiative. She described a recent community meeting entitled “Get Cured; Stay Cured” that included a panel of six self-identified PWUD who had accessed HCV treatment, either through the syringe exchange program or through the PCORI study for active injectors. The panelists described their treatment and how they were planning to avoid reinfection. At a similar event, “Tales from the Cured Community,” a panel discussed how they had been cured of HCV and what felt possible in their lives because of that cure. Burk suggested that such peer-to-peer presentations and conversations are often more effective than anything that can be done by health administrators, health department staff, or through pharmaceutical company commercial campaigns. Experience in San Francisco suggests that PWUD can be engaged effectively in HCV treatment, although they may need more support. She observed that many people receive HCV treatment before they have addressed all their other issues and stabilized in every possible way, but once they have been cured of HCV, they feel empowered to the extent that they become more adherent to their HIV medications, reduce their substance use, get housing, go back to work, and enact other positive changes.

To del Rio’s question about linking health departments to local-level service providers, Burk said that the End Hep C SF initiative has demon-

strated that part of this work falls under the auspices of traditional public health (e.g., testing and treating) and part involves community organizing. The latter does not need to be led by the health department, although it does help if it is supportive. Much of the work in building a community response to HCV involves identifying leaders in different systems, having those leaders identify what is needed, and determining how people can contribute. Anyone who wants to contribute can present an overview of HCV at shelters, drug treatment programs, mental health programs, and other settings. It is critical that anyone who engages with highly affected populations be empowered to explain what HCV is, how to get tested, and that it can be treated and cured. These presentations can also help to identify leaders among the various systems when they express interest in integrating HCV into their programs. Burk described an End Hep C SF survey tool that can be used to evaluate services around HCV in a specific setting; it has also been used to measure citywide capacity to address HCV and to ask agencies how they can be supported to do more.

Benjamin Linas, associate professor of medicine at Boston University, commented that the 15 percent seropositivity rate for HCV in San Francisco was interpreted as indicating that right spots are being reached, but he suggested that public health departments take such rates as indicating that not enough is being done and approaches need to be broader. Although the “right” positivity rate is unclear, the rate of 15 percent suggests overspecificity and not enough sensitivity about who is being screened. A lower positivity rate would suggest that all of the people are being found, which includes PWUD who engage with SSPs and others with risk for HCV who do not engage with SSPs (who are being missed if testing is only done in places where the seropositivity rate is 15 percent). Burk clarified that the rate of 15 percent reflects only one spoke of the work around HCV testing, such as community-based testing in high-prevalence settings using rapid HCV testing kits deployed by trained staff, as well as social media outreach. The resources are targeted to settings where high HCV prevalence is expected, and SFDPH would expect to see lowered prevalence in the coming years. The public and private sectors require different strategies to deal with HCV, given that the prevalence estimate is likely undercounting baby boomers who have been living with HCV for many years. End Hep C SF is doing academic detailing work with private clinics and systems to ensure that providers in lower-prevalence settings know that patients need to be tested and referred for treatment, because there is no longer any reason to wait for treatment.

IMPROVING CARE FOR HOSPITALIZED ADULTS WITH SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER

In her presentation on improving care for hospitalized adults with SUD, Honora Englander drew on her experiences as a hospitalist and as the director of the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT) at OHSU. IMPACT is an interprofessional inpatient addiction consult service that includes linkages to community addiction care for medically complex patients with SUD. To highlight some of the key issues that catalyzed her to take action as a clinician to improve SUD care, Englander described the case of a young woman who died after multiple hospitalizations for opioid use disorder (see Box 3-2).

Rationale for a Hospital-Based Addiction Medicine Service

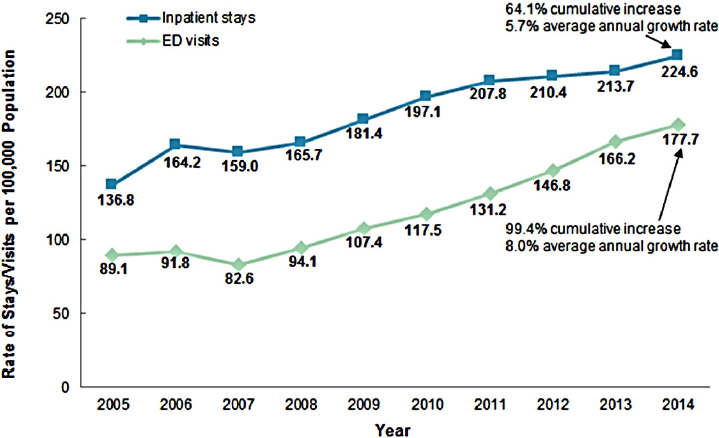

Opioid-related hospitalizations are on the rise across the United States, Englander warned. She cited data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)4 showing that between 2014 and 2015, there was a 64 percent cumulative increase in hospitalizations related to opioid use disorder (AHRQ, 2017) (see Figure 3-2). Costs are skyrocketing because of SUD, driven by high rates of hospitalizations and readmissions as well as lengthy hospital stays. Inpatient hospital charges in the United States related to opioid use disorder alone reached $15 billion in 2012, with more than $700 million charges related to serious infections such as endocarditis (AHRQ, 2009; Ronan and Herzig, 2016). Despite these intense and palpable costs—both financially and in terms of human lives—the health system has been very slow to respond, said Englander. Hospitalization often addresses patients’ acute medical illnesses but not the underlying cause of SUD, which leads to significant waste and very poor patient outcomes. Effective treatments exist but they are underused; despite such frequent interactions with hospitals, most people with SUD are not engaged in SUD treatment.

To begin exploring ways to improve the health system response to this mounting crisis, Englander and her colleagues led a mixed-method needs assessment at OHSU between September 2014 and April 2015 that surveyed 185 hospitalized adults (Englander et al., 2017; Velez et al., 2017). The results of the assessment revealed that “hospitalization is a reachable moment” that can be used to intervene, but it is not being effectively leveraged. Among the people surveyed, 57 percent of the high-risk alcohol users and 68 percent of the high-risk drug users reported that they wanted to cut back or quit; many of them also wanted to start medica-

___________________

4 AHRQ is in the Department of Health and Human Services.

tion for addiction treatment (MAT) in the hospital. The study also found that there were significant gap times for patients between hospitalization and initiating SUD treatment in community settings, indicating that the waiting lists are long. She explained that this delay undermines the effectiveness of care; for people who are started on methadone in the hospital, for example, having to wait for 1 week or more to receive community-based treatment can seem like a lifetime. The ability to start someone on a medication such as methadone or buprenorphine in a timely fashion will require building systems to facilitate rapid, streamlined access to care after hospitalization. She noted that the study also revealed that patients strongly value treatment choice as well as providers who understand SUD.

NOTE: ED = emergency department.

SOURCES: As presented by Honora Englander at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 12, 2018; adapted from AHRQ, 2017.

Designing a Hospital-Based Addiction Medicine Intervention

Englander explained they designed the IMPACT intervention by mapping the findings from the needs assessment onto the intervention’s key components. IMPACT’s inpatient addiction medicine consult service was developed to address the finding that OHSU hospital lacked the expertise to assess, engage, or initiate treatment for SUD and to leverage the reachable moment of hospitalization. She emphasized that this lack of existing expertise is widespread across hospitals nationwide. Initially, the service included a physician, a social worker, and a peer recovery mentor with lived experience in recovery, but the team has since expanded considerably to include more staff and now includes a part-time nurse practitioner and physician’s assistant. To address the lack of pathways to outpatient addiction care and the long wait times for community services, they developed rapid-access pathways to community SUD treatment. These pathways are supported through liaisons who have one foot in the SUD treatment world and one foot in the hospital, splitting their time between both teams and services.

Englander explained that the IMPACT team adopted a specific strategy to address the prolonged length of hospital stays for patients with SUD; she presented data showing that the actual length of stay tends to far exceed the expected length (Englander et al., 2017). She said that this is driven largely by patients with osteomyelitis and/or endocarditis, who require extremely long length of hospitalization because of social—not medical—vulnerability. She noted that patients stayed in the hospital for extended durations because there were no safe or supportive outpatient systems to complete a course of prolonged intravenous (IV) antibiotics through a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line, which goes from the outside of their body directly into the patient’s heart. To address the prolonged length of hospital stays for such patients and to increase community treatment options, IMPACT evolved a new care model called a Medically Enhanced Residential Treatment Model (MERT). Launched in 2015, MERT integrates the provision of IV antibiotics into residential addiction treatment.

Outcomes

Englander provided an overview of some initial outcomes of the IMPACT interventions. Between September 2015 and December 2017, 710 patients were served (mean age: 44.3 years; 59 percent male gender), 57 percent of whom were living in the Portland metro area and 45 percent of whom were homeless. Among those served, there was a wide and overlapping distribution between those with opioid use disorder (61 percent), alcohol use disorder (44 percent), and stimulant and methamphetamine use disorders (38 percent). Eighty-nine percent of people referred to IMPACT engaged with the team, meaning that they met IMPACT in the hospital and agreed to continue working with IMPACT on some level. The average number of physician encounters per patient is 3.3 (range: 0–33), and the average number of social work encounters per patient is 4 (range: 0–31). In terms of treatment, around 59 percent of people have had linkage recommended to community SUD treatment and 57 percent have had MAT, either in the hospital only or—more commonly—in the hospital with a planned linkage after hospitalization. Englander commented briefly on some of the IMPACT intervention outcomes that are not yet ready for formal reporting. They are tracking data that reflect hospital length-of-stay savings of approximately 450 to 500 hospital days per year. Studies are ongoing using Oregon Medicaid data to determine linkage to SUD treatment, health care use, and cost of care.

Perspectives from Patients and Providers

Englander shared data from qualitative work exploring perspectives of patients and providers about the IMPACT intervention (Englander et al., 2018). Before IMPACT, providers described widespread moral distress—and the feelings of futility, chaos, and anxiety—that arise from the struggles and burnout involved in caring for people with SUD. She quoted a cardiac surgeon as saying:

[Patients] ended up either dead or reinfected. Nobody wanted to do stuff because we felt it was futile. Well of course it’s futile . . . you’re basically trying to fix the symptoms. It’s like having a leaky roof and just running around with a bunch of buckets, which is like surgery. You gotta fix the roof . . . otherwise they will continue to inject bacteria into their bodies.

Englander reported that when asked to reflect on their experiences with IMPACT, providers described it as a “sea change” that “completely reframes” their understanding of addiction as “a medical condition that actually has a treatment.” She quoted one ward nurse as saying: “I think you feel more empowered when you’ve got the right medication . . . the knowledge and you feel like you have the resources. You actually feel like you’re making a difference.” The interprofessional providers IMPACT spoke with said that they highly valued rapid-access pathways to treatment. She quoted one provider as saying, “This relationship with [community treatment] . . . it’s like an answer to prayers,” and another hospitalist as remarking, “Starting them on [methadone or buprenorphine-naloxone] and then making the next step in the outpatient world happen has been huge. That transition is so critical; that’s been probably the biggest impact” (Englander et al., 2018).

Englander said that they are also carrying out work to understand the role of peers who have lived experience in recovery and are working as part of the IMPACT interprofessional team. According to one IMPACT patient:

[IMPACT peer] singularly, out of the whole group of them, she was honest, sincere, kind, didn’t put words in my mouth, didn’t say offensive things. . . . And she went to bat for me in the hospital, with my legal situation, with my family. She was there for me to help me with my son, wheeled me out on the wheelchair so I could smoke. Just an amazing person, very helpful, very good at her job.

Another patient said, “When [IMPACT peer] came in, she basically said if you wanna quit, great, if you don’t wanna quit, maybe we can get a plan figured out. She put the ball in my court, and she didn’t judge me.

She made me feel very comfortable.” From her perspective as a physician on the interprofessional IMPACT team, Englander remarked that when she works with people who have experienced significant trauma—who may be contemplative, precontemplative, or just not ready to engage—the experience is completely different when she is supported by a peer, whom she will often ask to take the lead in initiating the conversation. Peers can serve a hugely valuable role as “cultural brokers” and can demonstrate to the patient, in very clear and believable ways, that IMPACT—and Englander as a physician on the team—values the patient’s own experience.

Medically Enhanced Residential Treatment Model Outcomes

Englander noted the experience in implementing the part of the intervention called MERT that integrated IV antibiotics into residential treatment. To implement MERT, OHSU hospital partnered with a residential addiction treatment setting. Typically, residential addiction care involves 20 hours of groups per week, 1 hour of individual therapy per week, and onsite medication for addiction. With MERT, OHSU enhanced that treatment model to provide once daily IV antibiotic infusions as well as adding a new component of nursing care (including care management, accompaniment to medical visits, and medication support). OHSU also supported the team with weekly telemedicine rounds with the hospital’s infectious disease team.

Englander reported that despite the IMPACT team’s rigorous efforts to engage and recruit participants, only 7 of 45 potentially eligible participants were enrolled during the pilot period. Of those seven patients, only three completed their IV antibiotics and four left residential care against medical advice before completing their antibiotics (Englander et al., 2018). They found that despite all of the efforts toward designing the model, it was not actually what patients wanted. She outlined some of the key lessons learned from a mixed-methods study to understand and describe the feasibility and acceptability of MERT, understand implementation factors, and explore the lessons learned (Englander et al., 2018). In terms of recruitment barriers, the study found that patients were ambivalent toward residential treatment, they wanted to prioritize physical health needs, and they were afraid of untreated pain. Challenges related to retention for the seven patients who did enroll included high demands placed on patients by residential treatment; restrictive practices due to vigilance around PICC lines on the part of staff and other patients; and perceptions by staff and other residents that MERT patients “stood out” as “different.” Despite these challenge, the key informants interviewed

did feel that MERT was a positive construct and they were interested in exploring future models.

Englander maintained that the finding that this group of high-risk hospitalized adults did not want to go to residential treatment is one key implication of the MERT experience. Other implications include the need for flexible postacute care models that can engage patients across the precontemplative stage to the action stage of change, as well as the importance of integrating pain management, physical health care, and SUD treatment. While the experience with IMPACT demonstrates that hospitalization is a reachable moment, residential treatment represents a higher bar. The experience with MERT also highlights the role of iterative design processes that include ongoing feedback from adults with SUD. In developing IMPACT, OHSU carried out a patient needs assessment with a broad array of community stakeholders that included people from SUD treatment settings and other community mental health providers. She suggested that with MERT, they were not iterative enough in the design process with respect to engaging with active users and with people in recovery.

Future Directions

According to Englander, one future direction for IMPACT is to develop an IMPACT extension team to further address care needs for patients with SUD who need antibiotics. Her hope is that the extension team—which would be part of the IMPACT hospital-based team—would extend the team’s capacity to go into the community. The plan is to partner with transitional housing or a medical respite team through one of their key community partners (Central City Concern) in order to provide IV antibiotics and SUD care in those settings. They are also considering ways to extend care into skilled nursing facilities by providing new types of support in those settings, because the current skilled nursing facility model is highly problematic for many patients. It is difficult to convince skilled nursing facilities to accept patients who need SUD care, she explained, and those who are accepted often face perceived discrimination and other challenges around the patient experience.

Implications for Policy Makers

Englander concluded by outlining a set of implications for policy makers, the first being that hospitalization is a reachable moment to initiate and coordinate addiction care. It provides opportunities to reach people with severe medical illnesses and SUD who do not otherwise engage in primary care or behavioral health care. Treating SUD in hospital

settings also creates opportunities to improve providers’ experiences and help reduce provider burnout. Using a hospital-based team has the potential to reduce unnecessary hospital days and save costs, she added. Additional implications for policy makers are the need to establish treatment pathways spanning the hospital and community SUD treatment and the need to develop new care models that integrate IV antibiotics and SUD care. She also reminded the group that treating SUD in the hospital can and should be the standard of care.

A highly important implication is the value of an interprofessional team, said Englander, who reported that data from their experience with IMPACT strongly supports the complementary roles of providers (including physicians, nurse practitioners, and physicians’ assistants); social workers; and peers with lived experience in recovery. Peers represent a new workforce in most hospital settings, and when planning the workforce, it is critical to take into account the supervision, training, and support that these peers need to be successful in a very hierarchical hospital model. She advised that partnering with human resources, legal, and risk departments early on is very important, and noted that many peers have histories of incarceration that can pose stumbling blocks along the way. She also noted that peers can play a key role in patient engagement and system redesign.

Discussion

Carlos del Rio, professor of global health, epidemiology, and medicine at Emory University, asked Englander to elaborate on the barriers they faced when bringing peers into the hospital and how they overcame those barriers. Englander replied that it was not easy, but it was worth it. When discussing how to best initiate an addiction medicine consult service in hospital settings, she explained that defining the business case was very important, as was developing relationships with senior leadership in the hospital. When specifically discussing how to integrate peers into hospitals, she had presented the leadership with highlights from the patient needs assessment that underscored issues around institutional trauma and patient engagement. Before they began the hiring process, she convened a meeting with the hospital’s human resources, legal, and risk departments’ senior leadership to explain the program’s rationale and gain buy-in early on. She noted that OHSU also collaborated with an agency (Mental Health America of Oregon) to contract their peers. She also suggested leveraging relationships with community partners, who can help to make the case to hospital leadership based on their own experiences in nonhospital care settings.

EXPLORING CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES IN RURAL AMERICA

In his presentation, Nickolas Zaller explored the convergence of poverty, opioids, and infectious diseases in the American South, which he termed a “Southern syndemic.” The consequences of the opioid crisis in the United States are largely symptoms of deep-rooted, entrenched inequities stemming from poverty and other factors, which calls for broadening the conversation about addiction to include these causal forces. He focused on the rural South and the region’s vulnerability to opioid use and its complications. Many communities in rural America have not traditionally had to deal with opioid use because abuse of alcohol and simulants such as methamphetamines, crack, and cocaine have historically been the primary concerns. As a result, many communities in the South are ill-equipped and ill-prepared to deal with the opioid epidemic and associated surges in HIV incidence and prevalence. In those areas, access is very limited to the prevention and HIV care needed to address this “perfect storm” of poverty, opioids, and infectious diseases.

More than half of new cases of HIV in 2016 in the United States were reported in the South, Zaller said, and more than half of the 50 poorest counties in the United States are located in the broader Southern region (CDC, 2017). This overlap between rural geography in the South and very significant poverty has fueled the opioid epidemic, increases in HIV, and other consequences. Further compounding these problems are significant gaps in the continuum of care in rural areas throughout the country, but especially in the South. Systematic harm reduction programs and programs to address the root causes of HIV acquisition, such as opioid addiction, trauma, and poverty, are largely absent from many areas in the South (Schafer et al., 2017). He noted that in Scott County, Indiana, there was no access to syringe exchange and the state refused to authorize access until it was too late. Although Southern states accounted for 52 percent of all new HIV diagnoses in 2016, those states represented only 30 percent of all preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) users in 2016.5 There is an extreme scarcity of PrEP prescribers in states like Mississippi, which has one of the highest incidences of HIV in the country.

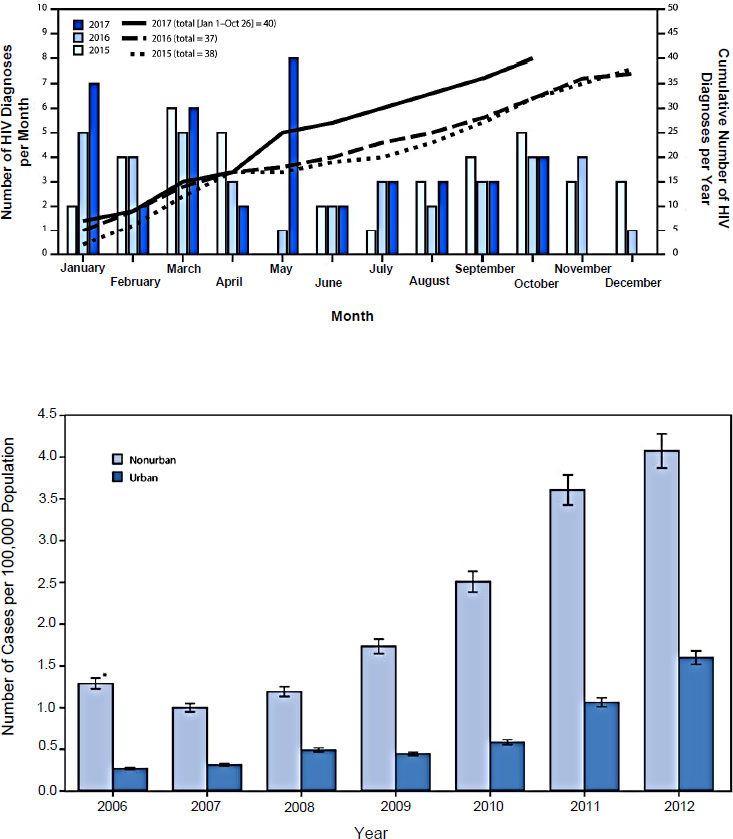

Zaller presented data on the spikes of HIV and HCV infections in rural areas of Southern states (see Figure 3-3). The top figure illustrates rising trends in the numbers of HIV diagnoses in rural West Virginia that warrant serious concern (Evans et al., 2018). Many of the diagnoses are attributable to injection drug use among people who have recently started

___________________

5 Data on rates of persons using PrEP in the United States in 2016 are from https://aidsvu.org (accessed April 12, 2018).

* 95% confidence interval.

SOURCES: As presented by Nickolas Zaller at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 12, 2018; Evans et al., 2018; Zibbell et al., 2015.

injecting and lack access to sterile syringes. The steady increase in HCV among people younger than 30 in rural areas of Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia (illustrated in the bottom figure) also demonstrates how this epidemic is sweeping across the country among people who start out using and then misusing prescribed opioids, with some transitioning to heroin (Zibbell et al., 2015). Increases in infectious diseases are striking communities that do not have the historical level of prevention and preparedness that other communities have, warned Zaller.

Opioid Use in the South: Transition from Prescribed Opioids to Heroin

Zaller traced the advent of opioid use in the South in recent years. There has been a tremendous surge in prescribing medications for pain to people in rural areas who often have jobs associated with a higher risk of injuries, such as coal mining and agricultural labor. He suggested that a cultural phenomenon has emerged whereby no amount of pain is acceptable: patients expect to receive medication for pain; providers are willing to prescribe them; and opioids are aggressively marketed. The heretofore low prevalence of opioids, coupled with the rural geography, means that there are limited prevention and treatment services. The transition from prescribed opioids to heroin is the other component of the epidemic, Zaller said, although good surveillance data on PWID is currently lacking across the South. One of the largest analyses found that incident use of heroin was 19 times more likely among those with prior nonmedical use of prescription opioids (Muhuri et al., 2013); another study found that the transition from nonmedical prescription opioid use to heroin appears to occur at a relatively low rate (Compton et al., 2016). However, overdose and treatment admissions associated with heroin are increasing in rural areas.

According to data from CDC on the age-adjusted deaths per 100,000 population from heroin in 2014 and 2015 by region, the South has an increasing number of heroin overdose deaths, but the rate is not increasing at the same magnitude as it is in the Midwest and the Northeast.6 He attributed this to lower rates of people who inject heroin and lower levels of fentanyl in the drug supply compared with the Northeast. Treatment admissions for opioid use are on the rise across Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, said Zaller. Between 2007 and 2012, the proportion of admissions to substance abuse treatment centers (among people aged 12–29 years) that were attributed to any opioid injection increased from around 5 percent to more than 18 percent, far exceeding

___________________

6 Data source: https://wonder.cdc.gov (accessed April 12, 2018).

the increase in admissions attributable to other drug injections (around 2 percent to 4 percent) (Zibbell et al., 2015). He noted that this increase in treatment admissions for heroin or injection opioids unsurprisingly overlaps with increases in HCV in those states during the same period.

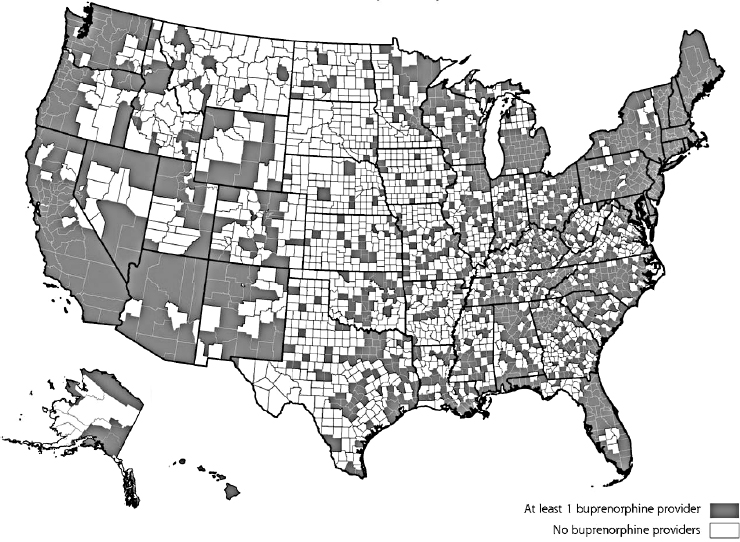

Zaller explained that this “tidal wave” of opioid use and its infectious disease consequences can be tracked spreading from the northeast of the country into Kentucky, North Carolina, West Virginia, and southern parts of Indiana and Ohio. Primary prevention is urgently needed in rural communities with extremely limited access to harm reduction resources and drug treatment, he cautioned. Urban areas that have been dealing with injection drug use for decades are seeing increasing proportions of overdose associated with fentanyl-laced heroin, but those areas often have more resources in place to stem the tide. This is evidenced by the locations of SSPs for PWID. One study found that in 2013, there were only 14 total SSPs in the entire South, compared with 43 in the Northeast and 61 in the West (with 20 SSPs in Washington state alone) (Des Jarlais et al., 2015). Of the few SSPs that do exist in the South, only one is located in a rural location. This problem is aggravated by the existing climate of tremendous stigma that makes it extremely challenging to provide syringe access in rural areas. Prevention from injection-related harms is not the only concern, continued Zaller. Access to physicians who have waivers to prescribe buprenorphine is very poor in large swaths of the South, compared to the high levels of coverage in the Northeast and along the West coast (see Figure 3-4). He noted that the states in the South that have many counties with no buprenorphine prescribers are the same states that have skyrocketing rates of opioid prescribing (Rosenblatt et al., 2015).

Prevention Opportunities in Arkansas

Zaller presented a case study on a prevention opportunity in Arkansas. He described the state as in some ways representative of the South, although he was wary of overgeneralizing about this very complicated region, in which each state has its own local culture, flavor, and politics. Arkansas ranked second in the nation in terms of opioid prescribing rates in 2016, with almost 115 prescriptions per 100 residents for its 3 million residents.7 According to data from the state’s prescription monitoring program from 2016, opioids were the most frequently sold drug type with almost 240 million pills sold; this is more than double the number of depressants sold and more than three times the number of stimulants

___________________

7 Data on state-by-state opioid prescribing rates are available at https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/maps/rxstate2016.html (accessed April 12, 2018).

SOURCES: As presented by Nickolas Zaller at the workshop Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic on March 12, 2018; Rosenblatt et al., 2015. Copyright 2018 by the Annals of Family Medicine, Inc.

sold.8 Similar trends of astronomical prescription rates occurred in states like Kentucky and West Virginia, he warned. In Arkansas, they are in the process of “shutting off the spigot” by going after so-called super-prescribers, but that alone will not solve the problem. Arkansas also ranks third in the nation for its high rates of nonmedical use of prescription pain relievers among people 12 and older (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015).

The data available show that heroin eventually becomes cheaper when people engage in nonmedical use of prescription opioids to a great enough extent. According to data from the state prescription monitoring program, Arkansas differs somewhat from other states in that women tend to get prescribed opioids at a significantly higher rate than men. The

___________________

8 Data on prescription drugs sold by class in Arkansas are available at http://www.arkansaspmp.com (accessed April 12, 2018).

proportion of overdose deaths among women in 2016 in Arkansas was 46 percent, ranking it third in the nation.9 Older people are highly vulnerable to overdose and are also receiving opioid prescriptions at a high and increasing rate, he added.

To work toward quelling the opioid epidemic, Zaller highlighted the importance of providing more treatment resources. A recent analysis found that the counties in Arkansas and Kentucky with the highest rates of overdose mortality are all very rural and all lead their respective states in opioid overdose deaths mortality. Four of those five counties in Arkansas with the highest overdose mortality rates (ranging from 20 to 22 per 100,000) have no physicians waivered to prescribe buprenorphine. According to anecdotal accounts, Zaller said that medical examiners in Arkansas are reluctant to classify overdose deaths because of the high level of stigmatization, which calls the accuracy of overdose death numbers into question. Kentucky has much higher rates of overdose mortality among its six most affected counties (ranging from 51 to 79 per 100,000), but five of those counties have no waivered physicians. This demonstrates the lack of infrastructure and capacity for treatment that is urgently needed in those communities, he said.

Ongoing Surveillance in County Jail

Zaller explained that Arkansas is situated in the “super-incarceration belt” that spans the South; the jail system in Arkansas has expanded to such an extent in just 5 years that it is now third in the nation, behind Texas and California. He described efforts to carry out ongoing surveillance of nonmedical use of prescription opioids at the county jail in Little Rock, Arkansas. They began by screening people who enter the jail for opioid use disorder and of almost 1,000 people screened, around 10 percent were identified as opioid dependent (Wickersham et al., 2015). Zaller surmised that this relatively low prevalence rate is attributable to under-reporting because people are reluctant to admit their illegal opioid use, but he said it serves as a reasonable proxy that can be used as a baseline for monitoring and tracking in subsequent years. More than 60 percent of jail detainees are African American, illustrating that there is a significant racial disparity at play in Arkansas—and across the South—in the disproportionate incarceration of African Americans. However, most of

___________________

9 Data on opioid overdose by gender are from a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of “Multiple Cause of Death 1999–2016” in the CDC WONDER Online Database, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. To request the data, see http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html (accessed April 12, 2018).

the detainees who were identified as having opioid use disorder in this sample were white. As an additional step, the jail staff began screening for HIV risk among those who reported injecting drugs; they also received funding to look at linkages to PrEP postrelease from the county jail. In January 2018, 77 detainees had reported injecting drugs prior to their most recent incarceration. They also found that while only around 20 percent of detainees in the jail are female, 30 percent of the sample is female—nearly 25 percent of whom reported sharing syringes. This is a serious concern, warned Zaller, because there is no access to SSP in the county where the jail is located.

Next Steps in Arkansas

Efforts are under way to address the lack of primary prevention in Arkansas, Zaller said. Partnerships with correctional facilities, such as the county jail, are enabling plans to link detainees to PrEP upon their release and facilitating research aimed at improving the quality of surveillance. Because the quality and reliability of surveillance in Arkansas is generally very poor, he noted, it is difficult to garner resources. The 21st Century Cures Act is expected to provide state treatment and response funding to support naloxone distribution as well as MAT expansion in primary care and in correctional institutions. This is critical because the state has very limited access to MAT. Methadone access is virtually nonexistent, and the numbers of buprenorphine prescribers per capita are very low; extended-release naltrexone is available but not yet covered by the Medicaid formulary. Zaller concluded by underscoring the urgent need for more data and resources for prevention, particularly in counties in the South where there are literally no services available to engage people.

Discussion

del Rio commented that Zaller carried out work in the Republic of Georgia years ago, which found that prescription opioids were also the most commonly injected drug and people who injected prescription opioids were less likely to be infected with HBV and HIV than people who injected street drugs. He asked whether safe injection sites have been considered as an intervention in Arkansas. Zaller said that they have not yet been considered, and furthermore, they do not actually know how prevalent injection is because of deep structural issues such as the tremendous amount of stigma surrounding both substance use and HIV. Some providers refuse Ryan White funding because they do not want to care for HIV patients. The state’s initial-phase focus is now on reining in doctors’ excessive prescribing of opioids for pain, which Zaller described as out of

control. Efforts to ramp up treatment access and distribute naloxone are being considered, he said, but resources will be the biggest barrier going forward. In Arkansas, Medicaid expansion set forth various restrictive work requirements, but the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) opened up unprecedented access to behavioral health care. If the ACA is repealed, he warned, it will be critical to find alternative ways to cover addiction treatment.

Judith Feinberg of West Virginia University reflected on her experience doing research in southern West Virginia, the center of the coal industry and the part of the state that is poorest and hardest hit by the opioid epidemic. Because the population is scattered across tiny communities in a state that is essentially one big mountain, the basic ability to travel from one community to another is the primary problem they face. “It really comes down to not having money for the gas or a car or a car that works,” she said. When social determinants of health are discussed, conversations should focus on how to get things done in the most practical way, she recommended. County health departments offer free testing for HBV, HCV, and HIV, but people cannot access them because most of those counties have no public transportation. They have discussed using ride-sharing services, she added, but cell coverage is very poor. Zaller remarked that other settings with large proportions of rural geographies face similar problems, because people without a source of transportation cannot be reasonably expected to travel long distances. They are already using telemedicine for basic services, such as stroke care and prenatal care for pregnant adolescents and other women with high-risk pregnancies who cannot access care otherwise (Arkansas has the highest rate of adolescent pregnancy in the nation). Given the success of those programs, he suggested that telemedicine could also be used to help treat addiction or to provide other mental health and psychiatric services. Another potential avenue would be to incorporate strategies used in global health to deal with access issues, he said, such as peer support and community health workers.

PANEL DISCUSSION

Sandy Springer, associate professor at the Yale School of Medicine, shared work she had recently presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections pertaining directly to the overlap between treatment of opioid use disorder and the HIV care continuum. Given that drug treatment is HIV prevention, she said, the aim should be to find the best and fastest way to start medication treatment for PWID and people who use opiates. Specifically, the goal with respect to HIV is to have 90 percent of patients with suppressed viral loads within 2 years

and to have every patient suppressed by 2030. Older data show that people who are incarcerated can get their viral loads suppressed before they are released, but 3 months after release, most of them are no longer suppressed—relapse to drug use is one of the major factors. She has been examining the use of effective, evidence-based interventions, including medications that can treat opiate use disorder. A previous study with buprenorphine in a nonrandomized control trial showed that staying on buprenorphine improves viral load suppression. Springer presented the results of their recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial among people who were incarcerated, which looked specifically at the effect of extended-release naltrexone on HIV viral suppression and whether people would continue to take naltrexone after release from the correctional facility.10 Eligibility criteria were designed to be minimally exclusive; participants could have a co-occurring SUD or mental illness. The intent-to-treat analysis demonstrated that the baseline characteristics of participants were broadly representative of the U.S. criminal justice system: predominantly racial/ethnic minorities, homeless people, and high rates of HCV comorbid infection. Within 6 months, participants who received placebo did not have improved viral suppression rates from baseline, but those given extended-release naltrexone were able to statistically significantly improve their viral suppression at 6 months postrelease. Multivariate regression analysis of other potential predictors indicates that the only one that stayed significant was receipt of extended-release naltrexone, which had an odds ratio of 2.902 in predicting viral suppression at less than 50 copies at 6 months postrelease. These results were replicated in another cohort as well. These results show that MAT for SUD combined with HIV treatment can lead to improvements in the continuum of care for people who are released from correctional facilities, said Springer.

del Rio pointed out a training gap: physicians need to be trained in opioid use disorder and how to provide MAT. Springer replied that there needs to be a systemic paradigm shift toward the idea that health care providers should treat everyone, including people with opiate addiction. del Rio commented on a related systemic issue—providers tend to feel like they have done their job just by giving patients a referral for substance abuse treatment and then hoping for the best. He asked about system interventions that could be used to address this problem. Todd Korthuis, program director for OHSU’s Addiction Medicine Fellowship, replied

___________________

10 She clarified that she was not endorsing extended-release naltrexone per se; it was chosen because at the time, it was the only long-acting injectable medication that could be started before release and then continued after release. Subsequently a long-acting buprenorphine (SUBLOCADE) has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

that the easy step is to make a concerted effort to encourage infectious disease physicians to obtain buprenorphine waivers. The harder steps involve building capacity to support providers working within a busy clinic schedule, in which HIV-infected patients are seen every 30 minutes or less. He suggested dovetailing with the emerging field of addiction medicine fellowships, as there are more than 45 1-year fellowships across the country already. He also raised the possibility of combining addiction medicine and infectious disease training for dual board certification. Zaller added that there are no infectious disease physicians in large parts of the country, so prevention will need to be provided by primary care and family medicine physicians who will need training.