2

Governance in Theory and Practice

This chapter summarizes the substantive presentations and accompanying discussions during plenary sessions that provided background and context for the participants. Copies of the presentations are also available on the project website.1

GOVERNANCE AS A LAYERED SYSTEM ACROSS THE RESEARCH ENTERPRISE

Following the introduction to the goals of the workshop, Alta Charo of the University of Wisconsin–Madison further elaborated on the concept of governance. Beginning at the international level, Charo emphasized that no single international institution has the mandate and capacity to provide oversight of dual use biotechnologies. She noted that a number of institutions provide or could provide a forum for discussions of dual use issues to develop common understandings and approaches to action. The cornerstone of the biological disarmament and nonproliferation regime is the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BWC), which builds on the 1925 Geneva Protocol banning the use of chemical and biological agents in war. The BWC addresses aspects of research indirectly through a prohibition on developing, producing, stockpiling, or otherwise acquir-

___________________

1 The project website is available at National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Governance of Dual Use Research in the Life Sciences: An International Workshop. Available at http://nas-sites.org/dels/events/dual-use-governance (accessed September 4, 2018).

ing or retaining “microbial or other biological agents, or toxins whatever their origin or method of production, of types and in quantities that have no justification for prophylactic, protective or other peaceful purposes” (Biological Weapons Convention, 1972). This indirect link to research provides little clarity on what types of research, including defensive research, are or are not acceptable. The treaty lacks formal mechanisms to verify compliance with its provisions or respond to violations, but serves as an important forum for discussions of dual use issues and a focus for international efforts to develop common understandings about research practices and oversight.

Charo next outlined a number of different approaches to analyzing the governance of biotechnology. One approach is to look at the actors involved. The work of Migone and Howlett (2009) on genomic policy making, for example, identified four key categories of actors. The first, governments, played a role as funders and regulators of research, and the second, universities, were producers of basic and applied research. The third category was private-sector bodies that functioned as users and producers of innovation (as well as financers and thereby sources of governance themselves). The final category was the public, who may be both consumers and critics.

A second approach is to focus on different regulatory issues, and Charo illustrated this by drawing on a framework developed for agricultural applications that included intellectual property rights, public information, retail and trade, food and health safety, consumer choice, and public research investment (Haga and Willard, 2006: 967). Charo explained that different regulatory issues faced differing research, legal, economic, educational, and acceptance challenges, and that the framework could be explored to look at how policy options stifle or promote research. She used issues around consumer choice to illustrate that the more technology is accepted, the more investment will flow into it and the larger the scale of research and development will be. This in turn changes how and where the technology is used in the food chain, affecting its capacity for diversion into destructive uses and the opportunities at which governance can take place.

Building on this point, Charo discussed the model developed by Robert Paarlberg in his studies of approaches to policy for genetically modified foods to illustrate how options operate along a spectrum, ranging from “promotional” to “preventive” (Paarlberg, 2000: 6). Using the case of intellectual property rights, she argued that patents could be seen as promotional because they encourage investment, whereas if intellectual property rights are eliminated, business interest is eliminated as well. For biosafety, policies could take either a promotional or a preventive approach. With the promotional approach, the technology is assumed to

be safe, and no specialized review is required without a a specific signal of hazard. By contrast, with a preventative approach, risk is assumed, and everything is viewed as dangerous until proven safe. In between lies a case-by-case review in which each use is examined, with neither safety nor hazard assumed. The speed of introduction into the market (or into research use) depends largely on which approach is taken.

Charo suggested that, while many people associate governance with regulations and laws, it would be more useful to think of governance as an “ecosystem” in which there are many different types of actors and multiple instruments that can be applied. The actors involved include funders of life sciences research; scientists from both academia and industry; institutions, such as universities and medical centers; journal publishers and others involved in disseminating research results; national governments; and regional and international bodies. The instruments include obvious measures such as treaties, laws, regulations, and policies, and restrictions on funding from public sources. In addition, other measures such as self-governance activities undertaken by the scientific community on a voluntary basis, are also important to responsible conduct of research, as had been the case in her experience with the governance of embryonic stem cell research.2 And she commented that there are also a number of other instruments that do not receive much attention in discussions of dual use issues, including intellectual property rights, restrictions by private funders, material transfer restrictions, oversight committees, and advisory bodies and stakeholder/advocacy groups.

She provided a number of specific examples of the different parts of the ecosystem, which are described in greater detail in Chapter 3. Charo began with formal legal measures, citing the obligations imposed at the international level by the BWC to put in place implementing legislation. As a second example she cited the work undertaken by the government of Pakistan, which included both a number of different legislative efforts related to dual use research as well as a number of administrative activities.

As an example of nonlegislative or regulatory measures, Charo cited the United Kingdom, where there have been a number of self-governance initiatives by the scientific community, including activities by the academic community, learned societies, and professional bodies to provide

___________________

2 The International Society for Stem Cell Research has developed widely accepted guidelines for the conduct of research using stem cells (see International Society for Stem Cell Research, Guidelines for Stem Cell Research and Clinical Translation). Available at http://www.isscr.org/membership/policy/2016-guidelines/guidelines-for-stem-cell-research-and-clinical-translation (accessed September 18, 2018).

education and training and to promote responsible research.3 She mentioned that, in Portugal, dual use research and Dual Use Research of Concern (DURC) are overseen by “biosecurity committees within institutions and informal bottom-up awareness-raising activities” (Millett, 2017). She also raised several examples of opportunities from education, including the case studies produced by the Federation of American Scientists and various resources from the Bradford Disarmament Research Centre (see Appendix E).

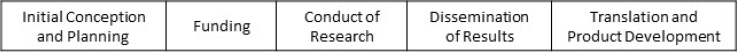

Charo stressed the importance of governance activities at every stage of the research “life cycle”: conception and initial planning; funding; conduct of research; dissemination of results; and translation and product development (see Figure 2-1).

At the conceptual or initial planning stage there are basic choices in approaching governance. Such choices in the private sector could include whether “dangerous” information would be subject to trade secrets and therefore hidden, with fewer people having open access, or taken forward through patents, thereby making potentially dangerous information open. In the U.S. context, the initial planning stage for publicly funded research would involve oversight bodies for biotechnology research, including reviews by an Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC), and since 2015, the additional policy changes, oversight, and consultations required in cases of research involving DURC agents and experiments (U.S. Government, 2014a).4 She elaborated on the 15 DURC agents and the 7 categories of

___________________

3 At the time of the workshop, the United Kingdom was finalizing its first Biological Security Strategy, released in July 2018 (UK Home Office, 2018).

4 U.S. Dual Use Research of Concern (DURC) policy applies to specific types of experiments with specified biological agents and toxins that “can be reasonably anticipated to provide knowledge, information, products, or technologies that could be directly misapplied to pose a significant threat with broad potential consequences to public health and safety, agricultural crops and other plants, animals, the environment, materiel, or national security” (U.S. Government, 2012: 1–2). The 15 agents and toxins are (a) avian influenza virus (highly pathogenic), (b) Bacillus anthracis, (c) botulinum neurotoxin, (d) Burkholderia mallei, (e) Burkholderia pseudomallei, (f) Ebola virus, (g) foot-and-mouth disease virus, (h) Francisella tularensis, (i) Marburg virus, (j) reconstructed 1918 Influenza virus, (k) rinderpest virus, (l) toxin-producing strains of Clostridium botulinum, (m) Variola major virus, (n) Variola minor virus, and (o) Yersinia pestis. The policy applies to an experiment if it “a) Enhances the harmful consequences of the agent or toxin; b) Disrupts immunity or the effectiveness of an immunization against the agent or toxin without clinical or agricultural justification; c) Confers to the agent or toxin resistance to clinically or agriculturally useful prophylactic or therapeutic interventions against that agent or toxin or facilitates their ability to evade detection methodologies; d) Increases the stability, transmissibility, or the ability to disseminate the agent or toxin; e) Alters the host range or tropism of the agent or toxin; f) Enhances the susceptibility of a host population to the agent or toxin; or g) Generates or reconstitutes an eradicated or extinct agent or toxin listed above” (U.S. Government, 2012: 7–8).

experiments that are the focus of current DURC policy to illustrate how this limited list was intended to identify core concerns. When it comes to institutional review under the DURC policy, the initial responsibility lies with the principal investigators (PIs) to identify potential DURC, which is then subject to an institutional review process. The objective is to identify the anticipated benefits, in conjunction with the risks, and if necessary develop a “risk mitigation plan.”

Funding decisions are a second important phase, and one that is subject to different national approaches. In the case of the United States, in 2017 the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy recommended, in addition to the existing DURC policy, prefunding review mechanisms for federal agencies that “conduct or support the creation, transfer, or use of enhanced pathogens of pandemic potential” (U.S. Government, 2017: 1). In the United Kingdom, the three largest funders of life sciences research, two government agencies and one private foundation, jointly require applicants to consider the risks of misuse associated with their proposal, and reviewers are given guidance for assessing cases (BBSRC et al., 2015). In the European Union, she noted that “research grant applications are subject to an ethical review panel and a security scrutiny committee can be convened if a research project has ethical or security implications” (Lentzos, 2015: 11).

A third phase identified by Charo was the conduct of research. Risk mitigation measures identified as relevant to this area include modifying the design or conduct of the research, enhancing security at laboratory facilities, and restrictions on personnel. Another measure that had received less attention in this phase was the incorporation of biological control mechanisms into research. For example, this approach is being employed in the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Safe Genes program.5 She suggested that such mechanisms can provide additional biological safeguards to complement the physical safeguards of the laboratory. Her final example of governance measures in the conduct of research was examining the efficacy of existing medical countermeasures and, where required, conducting experiments to determine their efficacy against agents and toxins resulting from dual use research.

___________________

5 Information on the program is available at Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, “Safe Genes.” Available at https://www.darpa.mil/program/safe-genes (accessed September 4, 2018).

The fourth phase of the research life cycle concerned the dissemination of results. Charo noted that the principle of free movement of ideas was crucial to journalism and science; yet at the same time there was some awareness that there could be occasions where the publication of information can be more harmful than helpful. She provided examples of past initiatives in this area, highlighting how these extend beyond formal classification processes. The first example was the 2003 statement by leading journals endorsing review of manuscripts for dual use material (Journal Editors and Authors Group, 2003), and the second was the white paper prepared by the Council of Science Editors, which made a similar call (Council of Science Editors, 2018).

Finally, in terms of the fifth phase, translation, Charo noted that there are export controls and technical innovations to control or limit spread (e.g., the DARPA Safe Genes program). Additionally, owners of intellectual property can act as a significant source of governance through the use of conditions on patent licenses and material transfer agreements to control uses and third-party dissemination. She provided an example of how this had been employed in the area of stem cells, wherein intellectual property owners were in a position to put conditions into every license stipulating that the intellectual property could (or could not) be used for cloning. She suggested that this was an existing avenue that needs to be given more attention.

Charo’s talk was followed by insights provided by Michele Garfinkel of the European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) from the perspective of the individual researcher, drawing on her experience and understanding of how researchers think and operate on a daily basis. Garfinkel argued that, in her experience, researchers generally want to do the right thing, are embedded in society, and primarily just want to do science. However, she continued, researchers do not have time to think in depth about concepts related to dual use governance, and she cautioned that if outreach and engagement are not done properly, dual use governance could become perceived as simply another element of the “bucket of things” that get in the way of research. Finding ways to avoid this reflexive rejection by researchers is essential to fostering effective governance.

Garfinkel also discussed the importance of intellectual property and funders, with the latter particularly important in the funding review process and in encouraging investigators to provide reassurance by supporting training in responsible research. In the current European context, she suggested that grant recipients often received no training in responsible research generally, let alone dual use–specific training. Accordingly, EMBO had provided training courses on the topic to fill the gaps, and she encouraged more efforts by funders to provide training for grantees.

Garfinkel also highlighted the importance of journals, given their

power to stop publications and also to assist researchers in understanding when their research might be dual use through the use of prepublication checklists, and through posteditorial, prepublication discussions with authors and editors. She explained that EMBO journals are run by professional editors who consider issues such as dual use as part of their publication process. In addition, EMBO makes use of an appointed board that includes people who are knowledgeable about dual use concerns. Many other journals, however, depend on volunteer academic editors who do not necessarily have a great deal of time or much knowledge of dual use issues and are therefore less well placed to support governance at this stage. She also noted that publication is the last chance to catch problems and, if an issue related to dual use is submitted to publication, then there must have been failures of oversight during the process. Garfinkel concluded by commenting that changes can take time to be fully implemented, even when ideas for change come from within the community.

Discussion

In the ensuing discussion, participants raised a number of points. One participant had concerns about private-sector research and the extent of controls in the entrepreneurial sector, arguing that there are no requirements to publish in the private sector and, in some cases, research only becomes visible through intellectual property. The participant suggested that government funding for academic research ensured that there is a degree of control, but not in the case in the private sector. Other participants countered this suggestion, arguing that many companies in the private sector had undertaken voluntary measures in support of dual use governance. It was suggested that this demonstrated some awareness of the challenges of dual use governance, as well as private-sector support for governance-related activities.

The role of publishers was also discussed further, with one participant echoing Garfinkel’s comments about some of the challenges faced by academic editors and the lack of knowledge of dual use–related issues among some editors. As other participants noted, this increased the chances that peer-review processes would fail to catch dual use issues. Others suggested that these challenges were being confounded by the emerging practice of prepublication, in which researchers post papers online prior to the completion of the peer-review process. The trend toward prepublication dissemination practices could considerably undermine the role of publishers as an intervention point for dual use governance.

The notion of an ecosystem of governance was also discussed, with one participant concerned that substantial changes in the regulatory ecosystem along with the rapid progress of science had rendered it dysfunc-

tional and there was a need for governments to catch up. Participants presented some initial thoughts about how this could be achieved, with one identifying a need for coordination through a clearinghouse-type mechanism so that people seeking advice and guidance on what to do with a manuscript that raises dual use concerns would know where to go. Another suggested there could be a scope for a system with different levels of scrutiny depending on the reputation of the organization. According to this logic, which built on the notion of “consistently trusted exporters,” organizations with higher standards would be subject to lower levels of oversight, whereas new actors or those with lower standards would be subject to more scrutiny.

LIFE SCIENCES GOVERNANCE IN ACTION

The second plenary, led by Iqbal Parker of the University of Cape Town, was divided into two sections. The first was an introduction to recent examples of life sciences research with dual use implications; the second was a panel with presentations providing examples of life sciences governance activities, outcomes, and lessons. He opened the plenary by describing some of his own experiences with biosafety and security governance activities undertaken in the context of South and sub-Saharan Africa as an example of the roles that academies of science can play. He described an assessment of existing legislation and regulations undertaken by the South African Academy of Sciences at the request of the South African government to identify strengths and weaknesses of such measures; provide a critical overview of measures in laboratories in southern Africa; conduct an assessment of dual use concerns; and evaluate existing measures and capacity to prevent natural, accidental, and deliberate events. The report, issued in 2015, raised concerns about both the legislation and the implementation of measures related to biosecurity and biosafety (Academy of Sciences of South Africa, 2015). A subsequent regional workshop for southern Africa on March 19 and 20, 2018, in Johannesburg, South Africa, provided an opportunity to discuss the topic further (Academy of Sciences of South Africa, 2018). Parker concluded by emphasizing the importance of avoiding cumbersome regulatory structures in these areas.

Examples of Research with Dual Use Implications

The first speaker, Piers Millett of the iGEM Foundation, provided an introduction to examples of recent life sciences research with dual use implications. Millett began with a short overview of the International Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM) competition, which engages

undergraduate and high school teams who spend a summer engineering biological systems using standardized parts to address real-world challenges.6 The speaker noted that last year some 6,000 participants from 340 teams around the world participated in iGEM. Millett then described how the iGEM safety committee has developed robust safety and security practices that are used to guide participants.

Millett stressed that even when research has dual use implications, invariably it has been undertaken for legitimate reasons. He echoed the Fink report’s conclusion that just because research had dual use implications did not mean it should not be done (NRC, 2004: 5–6), and he stated that there are a variety of different risk mitigation techniques that can be employed to minimize risks of dual use research. He then provided examples of actual experiments that have provoked controversies about potential dual use implications.

The first example he gave was the chemical synthesis of polio (Cello et al., 2002). The research demonstrated that the functional equivalent of a virus can be created through processes of chemical synthesis. If one can chemically synthesize viruses, it provides a new way for those with hostile intent to acquire dangerous pathogens and evade export controls. The second example was research to reconstruct the virus that caused the 1918 influenza pandemic (Tumpey et al., 2005). Millett noted that, prior to this research, the 1918 flu virus did not exist on the planet in a functional state and, as such, no one had access to it. However, this research potentially allowed nefarious actors to obtain things that would not otherwise exist.

Millett then described how it has now become possible to produce large pieces of DNA. This had raised concerns around whether it might be practically possible to synthetically produce large, complex viruses that do not have a natural reservoir. A particular concern identified by the security community was the creation of highly complex orthopox viruses. He pointed to research on the synthetic construction of infectious horsepox virus, which had been synthesized and rebooted by researchers,7 noting that this was important because of the similar relationship between horsepox and vaccinia virus vaccines (Noyce et al., 2018). The research thus raised biosecurity concerns as it demonstrated the possibility of making smallpox, which is otherwise only found in two secure laboratories in Russia and the United States. Additionally, the research raised concerns

___________________

6 More information about iGEM may be found at International Genetically Engineered Machine Competition. Available at http://igem.org/Main_Page (accessed September 4, 2018), with safety and security issues addressed at “Safety & Security at iGEM.” Available at http://igem.org/Safety (accessed September 4, 2018).

7 Additional steps are required to go from a syntheized viral genome to a viable organism. “The process of inducing raw genetic material to perform biological functions is known as ‘booting,’ a term borrowed from computer technology” (NASEM 2018: 194).

that it had changed the nature of the research field by both expanding knowledge of smallpox and lowering technical barriers to the creation of such viruses (DiEuliis et al., 2017).

Millett next provided examples of dual use research projects that could fall under each of the seven experiments of concern originally identified in the work of the Fink committee (NRC, 2004: 5–6) and now the focus of U.S. DURC policy. First was research that made vaccines ineffective. Research in this area was exemplified by the mousepox interleukin-4 (IL-4) experiment (Jackson et al., 2001), along with subsequent work on the expression of rabbit IL-4 (Kerr et al., 2004). Second were experiments that would confer resistance to antibiotics or antivirals. Millett indicated that this was evident in research on the regulators of multidrug resistance in Yersinia pestis (Galimand et al., 1997). Third was research on enhancing virulence, and he noted that research has been undertaken on elucidating variations in the nucleotide sequence of Ebola virus associated with increasing pathogenicity (Dowall et al., 2014). Fourth and fifth were experiments that involved increasing transmissibility of pathogens and expanding the host range, respectively. These aspects of DURC were clearly evident in the gain-of-function research conducted by Fouchier (Russell et al., 2012) and Kawaoka (Imai et al., 2012), which had been discussed at length (see, for example, NASEM, 2016; NRC, 2013, 2015). Sixth was research on the evasion of diagnostics. Millett identified a paper that studied the manipulation of surface proteins, as this essentially involved making diagnosis more difficult (Anisimov, 1999). Finally, with regard to improved weaponization, research had been undertaken that explored the role of large porous particles for pulmonary drug delivery (Edwards et al., 1997).

Millett proceeded by highlighting four conclusions he believed needed to be considered in the governance of dual use research in the life sciences. The first was the importance of “information hazard management.” He commented that governance measures have traditionally focused on physical controls and restricting access to physical materials. However, the examples discussed above illustrated the importance of looking not only at materials, but also at information and differentiating between the regulation of products on the one hand, and knowledge and information on the other. The latter, Millett argued, lay at the heart of the dual use issues and required policies of information hazard management and management of communications to minimize risks.

His second conclusion was the importance of addressing dual use issues prior to publication stage. He noted that in most of the research examples highlighted above, the debate over dual use took place at the publication stage. This was too late; governance efforts should not wait to address dual use at the point of publication. The third conclusion was the

need for greater awareness and willingness among scientists to address potential risks of research. This required making people aware of the potential for their work to be used for malicious purposes. He considered this to be a big, but not impossible, task. Fourth, and finally, he emphasized that this was not just about pathogens. The importance of thinking beyond pathogens was illustrated by his experience in iGEM, when one team came close to developing a gene drive. This was only picked up toward the end of the competition because none of the parts used were on iGEM control lists and it had not triggered any attention. Millett noted that iGEM had since created a specific gene drive policy under which teams are not allowed to create gene drives without permission from the safety committee.

Examples of Life Sciences Governance Activities, Outcomes, and Lessons

Following the introduction by Millet, the workshop moved to a panel format with a focus on examples of life sciences governance involving different activities and actors.

Governance of Dual Use Research in the Life Sciences in Australia

The first panel speaker was Julia Bowett of Australia’s Department of Defence Export Control Branch who drew from her expertise as both a technical adviser on export controls in the life sciences area and a co-chair in the Australia Group. Bowett introduced the Australia Group as an informal arrangement among 42 countries plus the European Union as an institution that meets annually to discuss trade restrictions on certain sensitive technologies of concern in order to counter the proliferation of chemical and biological weapons.8

She then outlined Australia’s approach to export controls, and the lead role of the Department of Defence in controlling traditional dual use items, that is, those with military utility as well as uses in legitimate research, commercial, or industrial uses. Controlled goods or technologies are listed in a document called the Defence and Strategic Goods List (or the DSGL), which is developed in conjunction with members of various international nonproliferation and export control regimes.9 The DSGL

___________________

8 More information may be found at The Australia Group. Available at https://australiagroup.net/en/index.html (accessed September 4, 2018).

9 The list and supporting information are available at Australian Government Department of Defence, “Defence and Strategic Goods List.” Available at http://www.defence.gov.au/ExportControls/DSGL.asp (accessed September 4, 2018).

is divided into two parts: the first contains goods and technologies that are designed for military purposes, such as munitions, explosives, and training equipment; the second contains dual use goods and technologies that may be used in a military program or could contribute to the development or production of chemical, biological, or nuclear weapons. This includes items such as chemicals, pathogens, toxins, electronics, computers, sensors and lasers, and navigation and avionics equipment. Bowett noted that some of these items required an export license if they met specific technical criteria.

With regard to the life sciences, the list of controlled items includes a number of human, animal, and plant pathogens and toxins (including various types of bacteria, viruses, and fungi), along with certain genetic materials and genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Listed agents are controlled under circumstances that include, for example, isolation of live pathogen cultures, extraction of a toxin, or inoculation of living material with a listed agent. Dual use equipment and chemicals are also regulated, including biological agent production equipment such as high-containment-level facilities, centrifugal separators, and fermenters; chemical production equipment such as reaction vessels, reactors, agitators, condensers, and pumps; and 65 chemical weapon precursors.

Regulations address two different types of exports. The first is tangible exports of physical items sent outside Australia by sea freight or air cargo or carried by a person; the second is the supply of intangible technology, which refers to non-physical assets such as information. The second category has the greatest connection to dual use research. The regulations for both types of exports apply to industry, universities, and research sectors.

Recognizing the complexities of the issues, the Australian government set out to create an open-source Life Sciences Guide (Australian Government Department of Defence, 2016). To ensure regular feedback from the life sciences sector in Australia, a working group made up of representatives from universities, research institutes, public health networks, and other government agencies was created. Consultations with the working group extended for approximately 2 years over the various iterations of the Guide. Bowett commented that the Guide included all of the controls that might apply to life scientists and the exemptions the Australian government makes available to them. The working group also addressed sector-specific concerns using scenarios and she provided several illustrative examples.

The single biggest challenge for the regime, Bowett argued, is dealing with the intangible transfer of technology and the electronic supply of information over email or via cloud computing. This is a challenge for governments the world over, not just Australia. As an example of intan-

gible technology supply that would require a permit, she presented the case in which someone in Australia collaborates with an entity in Japan to create a new method of developing an export-controlled pathogen (e.g., Lassa fever virus), and the Australian entity emails the research findings to the Japanese entity. A second challenge is understanding university culture, and she posited there was a need to find a very fine balance between the needs of the research community in Australia and the requirements of the counterproliferation obligations that the Australian government has undertaken. A related challenge is addressing misunderstandings, such as explaining specifically where the thresholds for export controls lie, when researchers should talk to the government, and what amounts to a “supply” of technology.

Bowett concluded by stressing the importance of providing information to the regulated community and elaborated on the extensive outreach that Australian export control authorities had conducted to universities, public health networks, and companies, including through a “capital cities roadshow” each year. She commented that the roadshow sessions in particular invariably reached capacity. Every university in Australia now has an export control manager who serves as a point of contact for the regulators, and with whom they maintain good working relationships. She stated that if a university or company requests assistance for a major project, the authorities invariably visited them and walked them through the export controls that apply, explaining what they have to do. Additionally, the team at the Australian Defence Export Controls Branch provided a free export control helpline and frequently presented at conferences and expos.

Governance of Dual Use Research in the Life Sciences

Joseph Kanabrocki of The University of Chicago, the second panelist, introduced himself as a faculty member who also oversaw the research safety office. To begin, he provided an overview of The University of Chicago, indicating that it supports nearly $500 million in externally sponsored research annually and involves approximately 400 principal investigator (PI)-led research groups, with approximately 300 PI laboratories in the Biological Sciences Division.

He indicated that the university had two IBCs; one on the main campus at Hyde Park and a second in its Select Agent High Containment Facility. When the U.S. government created its policies for oversight of DURC for institutions receiving federal funds in 2014, it also included a requirement to create an Institutional Review Entity (IRE) in addition to the IBC (U.S. Government, 2014a). In the case of the University, its IRE (also called the DURC Task Force) includes a diverse range of mem-

bers: those involved in DURC, as well as participants from the Office of Research, which includes those dealing with export controls, the Office of General Counsel, and faculty members who are also members of one or both of the University’s IBCs. He commented that DURC was the driving force for this task force but the program was not limited to the 15 agents and 7 experimental approaches detailed in the U.S. DURC policy.

The University of Chicago’s DURC governance structure begins with the PIs, who are in constant communication with the IBC. The Office of Research Administration works with PIs and funding agencies, thereby closing the circle. In their traditional role, the IBCs require the registration of recombinant DNA work and/or any project that involves human, animal, or plant pathogens. When protocols for associated work are registered, the IBCs attach certain training requirements and Kanabrocki indicated that no protocol can be approved without the training system attached to it. Additionally, PIs are required to answer questions about whether the proposed research plan would involve experiments in any of the seven areas of concern identified by the Fink committee (NRC, 2004: 5–6). He commented that sometimes PIs answer “no” to all the questions because they do not understand what they are working with; others check “yes” to ones that are not relevant. Yet although there may be confusion over the questions, he argued that the process of using this questionnaire was a form of education in and of itself.

Kanabrocki said there were two types of review for DURC: the first was at the beginning when the proposal is written, when they undertook an initial review, and a second at the end, when the manuscripts are written. Based on the outcome of the first review, the DURC Task Force provides binding recommendations and supervision related to the conduct of the DURC. The University has developed a Framework for Review of Risk Mitigation Plans with four steps, following the guidance provided by the U.S. government. The first involves “[a review of] the research to verify that it still directly involves nonattenuated forms of one or more of the listed agents.” The second step involves “[assessing] whether the research still produces, aims to produce, or can be reasonably anticipated to produce one or more of the listed experimental effects.” The third step is to “determine whether the research still meets the definition of DURC,” and the fourth is to “review and, as necessary, revise the risk mitigation plan” (U.S. Government, 2014b: 44).

He also described a number of possible risk mitigation measures. These included consideration of—and changes to—the “timing, mode, or venue of communication for the DURC in question,” as well as “[establishing] a mechanism for prepublication or precommunication review by the institution and/or the appropriate USG funding agency” (U.S. Government, 2014b: 38). On the latter point, he commented that mecha-

nisms for prepublication review are often not well received and PIs are eager to publish their work. Other risk mitigation measures employed in communicating DURC could include adding material to the text to “emphasize the biosafety and biosecurity measures that were in place throughout the course of the research” (U.S. Government, 2014b: 38), and placing emphasis on the public health benefits, thereby focusing attention on the benefits rather than the potential harm.

He indicated that there were common elements in all of the University’s DURC risk mitigation plans, including a description of the enhanced biosafety and biosecurity measures in place in all formal communications (e.g., manuscript, abstract, poster, etc.); training investigators about DURC; the provision of a forum for ongoing monitoring of DURC projects; and the creation of a code of ethical conduct for all researchers. In addition, for work involving Select Agents, the code is signed annually by all investigators and discussed during annual interviews. The code includes commitments to standard practices of responsible conduct, but also an obligation to report accidents and injuries as well as suspicious behavior.

Kanabrocki concluded by addressing some programmatic limitations experienced by the university. For example, the program was limited to the life sciences as the university did not have an in-house mechanism to review physical science experiments as systematically as it does life sciences experiments. Moreover, the current regulatory framework is list based, which makes little sense to him as some of the experiments do not fit easily within the categories. He also acknowledged that there is limited screening of molecular engineering and synthetic biology research and the current mechanisms for dual use research screening rely on a risk mitigation platform originally established for the oversight of work with recombinant DNA. Nonetheless, he concluded that it was a start and the current screening paradigm provides a platform for the development and delivery of dual use research education and puts consideration of DURC on investigators’ radar screens.

Role of Young Academies in Promoting Responsible Conduct of Research: The Malaysian Experience

The third panelist was Abhi Veerakumarasivam from Sunway University. Veerakumarasivam began by emphasizing the importance of striking a balance between research activity for progress on the one hand, and regulations intended to protect on the other. He presented presented citation data from different countries between 1996 and 2016 indicating the sizeable number of papers produced by Southeast Asian countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. This

reflects the aspirations of many such countries to become world class in scientific research and, they hoped, improve their economic situation. Yet as research became more extensive, so too did the spotlight on research concerns, and he indicated that they had experiences with both high-profile retractions of publications and apprehensions over nefarious activities. This underscored his argument for the need to balance research and protection, taking into account that much of the research was undertaken to serve humanity.

Veerakumarasivam outlined the history of the responsible conduct of research program in Malaysia beginning with a workshop in 2013 that was organized by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (NAS), which provided many in the region with an introduction to the concept of responsible conduct of research (RCR).10 He indicated that the introduction to active learning pedagogy as part of the workshop had an immediate impact, as they had not thought much about this issue before. He further noted the importance of collegiality at this event and outlined how subsequently the NAS allocated funding for four further workshops to introduce RCR and active learning. These workshops helped in building critical capacity, generating momentum, and, perhaps more importantly, developing a greater understanding of the local context.

He discussed the levels of awareness among the participants, indicating that the majority had never attended RCR training and were unaware of whether their universities provided clear guidance for addressing research misconduct. He suggested that biosecurity and dual use research were the least understood in terms of RCR knowledge and the workshops were able to “double” knowledge levels. It was also noted that there were large variations in awareness evident across individuals and, as he pointed out, when asked the question, “When you witness your colleague committing research misconduct, what would you do?” senior experienced researchers (i.e., those with more than 10 years of experience) were more inclined to inaction. This suggested to him that there was utility in the voices of young people.

Next, he discussed some of the challenges to global harmonization and identified a number of issues. The first was the desire for greater national competitiveness; the second was that dual use issues were seen by some as a Western initiative and were met with both skepticism and cynicism. He suggested this perhaps reflected the inability to contextualize on the part of some. The third challenge to global harmonization was gaps in the capacity of relevant actors to conduct, assess, and monitor

___________________

10 For further information, see National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, “Educational Institute on Responsible Science (SE Asia).” Available at http://nas-sites.org/responsiblescience/iircs/institutes/institute-in-se-asia (accessed September 20, 2018).

activities. A final challenge was posed by differences in religion, culture, and values that may affect which issues are perceived to be of greatest relevance and concern. He also noted that there were issues with risk perception and response and, even when hazards are known, risks are still taken, with risk perception often proving to be context specific.

Veerakumarasivam also discussed the results of a report from the Global Young Academy about the heterogeneity of the global state of young scientists in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) (Geffers et al., 2017) and emphasized the importance of creating spaces and training opportunities for young scientists in the region. He noted that his experience in the ASEAN science leadership program suggested that young people are both concerned about and interested in topics related to responsible conduct. He decribed the launch of the Malaysian code of responsible conduct of research and the establishment of an educational module (Chau et al., 2018). He added that the educational module included a dedicated chapter on addressing dual use issues in the Malaysian context. Veerakumarasivam noted that they had tried to address issues beyond life sciences and dual use, and to engage engineers and physicists, for example. He added that there was an ASEAN young scientists group trying to create a larger group of trainers in this area, and concluded by noting that first, the experience thus far would not have been possible without the help of the NAS, and second, that education is key and young scientists are important.

Neuroenhancement, Responsible Research, and Innovation

The final panel speaker was Agnes Allansdottir of the Toscana Life Sciences Foundation, who spoke about a project that illustrated governance of research with dual use potential beyond pathogens. Neuroenhancement, Responsible Research, and Innovation (NERRI) was funded by DG Research in the European Commission and comprised a consortium of institutions in 11 European countries and the United States.11 It was established to explore the means to promote a broad societal debate, leading to proposals for responsible research and innovation (RRI) in neuroscience, specifically neuroenhancement (NE).

Allansdottir began with a definition of responsible research and innovation from the work of von Schomberg:

___________________

11 Additional information is available at “Final Report Summary: NERRI (Neuro-Enhancement: Responsible Research and Innovation).” Available at https://cordis.europa.eu/result/rcn/192408_en.html (accessed September 4, 2018).

Responsible Research and Innovation is a transparent, interactive process by which societal actors and innovators become mutually responsive to each other with a view to the (ethical) acceptability, sustainability and societal desirability of the innovation process and its marketable products (in order to allow a proper embedding of scientific and technological advances in our society). (von Schomberg, 2013: 19)

For the purposes of the workshop discussion, Allansdottir noted four key dimensions of RRI that were taken into account: anticipation, reflexivity, inclusiveness, and responsiveness (Stilgoe et al., 2013). “Anticipation” refers primarily to the preliminary stages of what has been termed “anticipatory governance” in the sense of actors involved in scientific and technological development collectively attempting to forecast the future trajectories of developments, including social, ethical, and legal aspects. In other words, what visions of society would potential developments of NE give rise to? “Reflexivity” refers to taking into account that all issues can have diverse and divergent framing. For example, particular developments in NE within a strictly medical context might take on a completely different framing and connotations outside that medical context. In other words, reflexivity imposes on those developing science and technology “to blur the boundary between their role responsibilities and wider, moral responsibilities” (Stilgoe et al., 2013: 1571). “Inclusiveness” implies going beyond consultations with stakeholders and shareholders in an attempt to invite wider society into a reasoned dialogue over a given issue or development. The NERRI project, along with other projects publicly funded by the European Commission, aimed to explore the way inclusiveness could potentially be reached in different cultures and countries and across segments of society. “Responsiveness” refers to how activities structured along the first three dimensions will lead to actual policy outcomes, that is, how the knowledge and experiences captured in the course of public engagement activities can be made relevant to policy makers and affect policy-making processes. She suggested that these dimensions should be considered as guidelines for work in progress.

As described by Allansdottir, NERRI built on the conceptual tools of mutual learning exercises in which experts and lay audiences discuss and learn from each other, as opposed to experts simply informing lay people about “facts” (Zwart et al., 2017). The project was inspired by the idea of decentralization, with the aim of including a wide variety of voices in a reasoned societal dialogue to make science and technology more relevant to society. Project partners conducted more than 60 events, bringing together a range of stakeholders and members of the public to discuss the feasibility, ethical acceptability, and social desirability of neuroenhancement. A variety of formats were used, from small discussion groups with a dozen selected participants to large open fora with hundreds of attend-

ees, from science cafés to activities in major exhibitions, and from theater plays to hands-on “hackathons” where enthusiasts engaged in NE design and development. Participants were always encouraged to contribute their own moral judgments and viewpoints.

The project focused on four areas of neuroenhancement: pharmacological, brain stimulation (Bard et al., 2018), gene modification (Gaskell et al., 2017), and an open-ended category of “other means.” Allansdottir indicated that the project did this in two different contexts. The first focused on employment and the second on education in all participating countries, and in this context raised questions: Was it acceptable to give children stimulants to increase their educational achievement? Would it be acceptable to take stimulants? Will NE help or hinder growing demands and pressures on the workforce? These initial questions were developed as the technology evolved and became contextualized. A small dedicated case study focusing on NE in the military context was carried out by partners from the United Kingdom and Italy. In the case of Italy, this followed a 2013 report that provided advice to the Italian government on cognitive enhancement and a second document on the use of human enhancement in the military context.12 A preliminary workshop with military personnel used a vignette approach to stimulate discussion by presenting participants with a story to discuss from their own perspectives. The project team employed the following vignettes:

- Pharmacological stimulation: The protagonist is a pilot about to be deployed on a high-stakes mission.

- Neuroprosthetics: A soldier gets a “better” arm following an accident in order for him to return to combat.

- Moral enhancement: Empathy-enhancing drugs are used in interrogations of terrorist suspects and gathering of intelligence.

- Neural implants: In futuristic settings, implants allow military personnel to become more efficient and effective in combat.

She provided some elaboration on the neuroprosthetic vignette, presenting the story that was discussed in order to elicit the views of military

___________________

12 Further information may be found at Italian Committee for Bioethics (Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri). Available at http://bioetica.governo.it/en (accessed September 4, 2018). Reports on “Human rights, medical ethics and enhancement technologies in military contexts” and “Neuroscience and pharmacological cognitive enhancement: bioethical aspects” are compiled in Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri Segretariato Generale. Italian National Bioethics Committee Opinions 2013–2014. Roma: Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, Dipartimento per l’informazione e l’Editoria. Available at http://bioetica.governo.it/media/3518/9_opinions_2013-2014.pdf (accessed October 2, 2018).

personnel and stimulate thinking around issues that might not have otherwise been considered.

Allansdottir concluded with some reflections on the lessons from the NERRI experience. She indicated that such discussions can stimulate wider thinking, including around topics not previously given consideration. Other lessons from the project included the tendency toward “hype” rather than reality and the difficulties derived from the fact that NE is not a single technology but cuts across a range of domains of research that have implications for potential dual use. The distinction between restoration and enhancement, for example, is blurred, yet important. Public engagement was enlightening and necessary, but the project found that the wider public’s points of view diverge. She argued that established medical regulation is insufficient in the case of NE and that a more comprehensive governance framework is needed, and a fundamental rights approach might be considered. Finally, she noted that resilient governance should involve citizens and insights from the social sciences.

Discussion

The panel stimulated a number of questions, particularly around the Australian approach to export controls. One participant asked how the protocol for export controls was written and what happens if someone does not report an export. Others asked about feedback from the scientific community related to export controls and whether, for example, export licenses were required for speaking at a conference or applied to vaccine production. Others raised the issue of whether export controls on equipment, such as biosafety cabinets, were outdated.

Bowett provided a detailed response, indicating that they did not require scientists to obtain an export license to present at a conference, and that they had set the control threshold very high so the content of a PowerPoint presentation overseas would not be detailed enough to cross the threshold. Bowett reiterated the difficulties posed by export controls on intangible technology, highlighting the importance of outreach to deal with this and explaining how they engaged with universities and the circumstances in which researchers would need to come and speak with her organization. She indicated that it was very difficult to police emails, but through cooperation with colleagues in other government departments there was a legal route available to gain access to them if required. In relation to the question about vaccine production, Bowett noted that it was exempt from export controls if the vaccine was already developed or was going through certification. Pertaining to the question about biosafety cabinets, she noted that current control lists were a product of the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s, and, although non-State actors do not necessarily

need 100-liter fermenters, such lists nonetheless provide a basis for talking to universities. Finally, Bowett indicated that the program issues about 4,000 permits per year, of which 350 permits are for the life sciences, and added that the vast majority of permits are not for intangible technology; in the past 3 years they have only had two intangible technology export requests in the life sciences area.

FOSTERING CHANGE

In addition to presentations on the concept of governance and examples of a range of governance activities, this workshop included presentations drawing on insights from the behavioral and social sciences to inform the participants’ discussions of potential strategies and activities to enhance current approaches to the oversight of dual use research.

Coalface Governance: Fostering Daily Compliance in Laboratories

The first speaker was Ruthanne Huising of Emlyon Business School, a sociologist by training, who studied biosafety and security regulation and sought to translate her research into action at the working level. She argued that, based on her research and experience, improved compliance with regulations was needed. Making improvements required, in part, better understanding of both the way scientists and regulators interact in the workplace and of the challenges of translating normative codes and regulatory measures into action in laboratories.

Huising began with the example of how to get people to wear laboratory coats to illustrate some of the challenges of governance in real workplace settings, before relating this to the more sophisticated topic of dual use.

She outlined issues with compliance in academic laboratories, noting that most researchers’ experience with compliance requests is as an intrusion on—and impediment to—their work (Gray and Silbey, 2014; Smith-Doerr and Vardi, 2015). Moreover, researchers often communicated safety measures as peripheral to core research work and delegated them to students and laboratory technicians (Huising and Silbey, 2013). She suggested that researchers will incorporate safety features into their practices when the features either align with efforts to control physical matter or help them do their research better (Bruns, 2009). There is variation in responses to regulation across disciplines. Chemists, for example, are in general significantly more accepting of regulation than biologists, and she attributed the differences to the fields’ epistemologies, the tools used, and the ways chemists and biologists organized their laboratories. Huising commented that most violations are minor housekeeping prob-

lems but added that this should not mean violators are not held accountable since smaller violations can trigger bigger problems. She also noted that evidence suggests that a small number of laboratories account for the majority of violations (Basbug et al., 2016).

Huising then addressed the question of what was different about academic laboratories. Although corporate and diagnostic laboratories were generally doing quite well in terms of compliance, the structure of academic environments, the employment relationships, resources, rules and procedures, and work were different, at least from a North American perspective. In North American academic laboratories, PIs often have significant authority over their laboratories. Moreover, PIs report to their peers and department chairs; these are rotating positions, so there is a form of collegial governance in which, to some extent, the laboratories are regulating each other, rather than adopting the hierarchical model of decision making that was more commonly associated with corporate or diagnostic laboratories. Huising argued that the implementation of basic human resources policies is also different. In the academic context, implementation may vary considerably; for example, postdoctoral students are not employees of the laboratory, and laboratory membership is often rotating and determined by the PI. This contrasts with the corporate approach, in which the rules and procedures from the central human resources office that cover employes are followed much more consistently. Compared with corporate or diagnostic laboratories, academic laboratories also have less stability and cyclical resource flows, along with rules and procedures that are often quite localized and tacitly passed on through training. Moreover, in academic laboratories organizational-level rules were secondary, an important contrast with the corporate approach in which rules and procedures were developed at the organizational level in written form. The speaker also suggested that, in terms of the work processes and the expertise of personnel, academic laboratories tended to be more collaborative and open, with considerable variation across laboratories within the same institution.

Huising turned to discuss the roles of the professional bureaucracy and organizational cultures, suggesting that academics do not always respect bureaucracies. Yet, professional bureaucracies have significant implications for safety and security. They determine the responsibility for legal and administrative requirements, maintain the authority to enforce requirements (formally or informally), and hold control over the resources for compliance activities and equipment. Bureaucracies also represent allocations of authority over people working in laboratories.

In terms of organizational culture, she noted the increased attention to the topic by policy makers (Silbey, 2009). Organizational culture was seen as both a problem—“lax” or “insufficient cultures”—and a solution,

as evident in proposals for building a “culture of safety” or “changing the culture.” As such, organizational culture was understood by policy makers and managers as a tool to change and manage behavior. She suggested that the focus on change at the organizational level was overshadowing other important complementary levers to modify individual and collective behavior and reduce noncompliance in the laboratory setting (Huising and Silbey, 2018). One approach is the notion of “nudges,” which focus on relatively small changes that can nonetheless affect individual behavior and prompt improved compliance (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). A second is “relational,” such as networks that can be developed to resolve logistical barriers to compliance that are often overlooked. A third approach is through the bureaucracy and bureaucratic process, such as written policies, placement of signs and reminders, the training of staff, and the inspection and correction regime. These important functions are usually sustained by professional staff, typically biosafety officers. The example of laboratory coats mentioned above illustrates how these complementary approaches could be applied. She noted that researchers not wearing laboratory coats in laboratories was a common infraction and something scientists openly admitted, in part, she suggested, because wearing them was perceived as a signal that the wearer was an amateur.

Beginning with nudges, she suggested that changes to choices about laboratory design or work routines, along with the placement of signs, messages, and personalized reminders, could be considered nudges intended to change how people think about simple compliance issues. More specifically, repositioning sinks or the location where laboratory coats were hung could affect whether people washed their hands and used their laboratory coats.

The second lever is the concept of “relational regulation,” which involves networks and teams that work beyond their official roles to understand compliance issues and craft local, pragmatic solutions (Huising and Silbey, 2018). She commented that there are numerous logistical issues tied to compliance. In the case of laboratory coats, the challenges include who supplies the coats, what type of coat should be worn, and who pays for, cleans, and replaces the coats. While these may seem like petty issues, they are nonetheless logistical barriers to compliance. Moreover, when identified, such issues are usually resolved by people who go beyond their formal roles, departments, and responsibility to solve the types of problems that often fall through the cracks. Such relational regulations are necessary to supplement bureaucratic means that often overlook such problems.

Huising stressed the importance of the role of techno-legal experts in organizations. Specifically, organizations depend on environment, health, and safety (EHS) staff (i.e., biosafety officers) to ensure compliance and

- walk researchers through record keeping, inspections, and corrections, and maintain compliance (Huising, 2015);

- negotiate increased daily compliance by working in laboratories, generating familiarity, trust, and relationships; and

- anticipate problems and identify emerging dangers.

She indicated that these are the people who are able to walk past a laboratory familiar to them and swiftly determine if something is wrong. She also noted that these “boots on the ground” are chronically underfunded and experience challenges to their authority.

As the final lever, Huising turned to organizational culture as one that should be supplemented. She explained the concept of organizational culture change as a conscious attempt to influence the action, language, thoughts, and feelings of employees. Changing organizational cultures can involve the promotion of values and norms reinforced through organizational rituals, symbols, language, stories, and other artifacts. However, she cautioned that culture change is both an expensive and long-term project, adding that anyone who wants culture change needs to secure the support of senior managers and sufficient funding. She also suggested that a key element of cultural change was determined by human resource practices and leadership.

Returning to the laboratory coat example, she commented that wearing laboratory coats was not common in promotional material for grant winners and questioned what message this sent to students. This reinforced her point that cultural change has to start at the top with those who control resources and seek to shape values and norms and to make decisions that align with those norms.

In her final comments, Huising returned to her earlier point that a very small number of laboratories were particularly problematic and asked whether, although controversial, it may be time to start profiling them, noting that laboratories employing tenured staff and receiving funding windfalls were particularly prone to a large number of violations. She concluded by discussing the notion of “coalface” (i.e., front-line) governance and the importance of structural factors, noting that the distribution of authority and resources and the structure of employment have important implications for compliance. She suggested that, for the purpose of the governance of dual use research in the life sciences, multiple levers should be used simultaneously and recognition given to the central role for biological safety professionals. She also noted that it was important to understand the implications of biosafety professionals moving into the field of biosecurity.

Social, Behavioral, and Decision Science in Risk Management

Baruch Fischhoff of Carnegie Mellon University spoke on the role of social, behavioral, and decision sciences in risk management. He began by indicating that there were five different aspects of human behavior in risk management in this area:

- Biosafety—how materials are handled;

- Biosecurity—how other parties might use research, perhaps for nefarious purposes;

- Risk analysis—how one predicts the risks (and benefits), a human activity that is difficult to quantify;

- Risk management—how one addresses risks (and the missed benefits of not fully taking advantage of someone’s science); and

- Risk communication—how one addresses others’ concerns and manages the risks in a way that is perceived as appropriate.

Fischhoff argued that research has found that how people assess situations and the probability of things happening follows many simple principles. He gave several examples.

- People are good at tracking what they see, but not at detecting sample bias.

- People have limited ability to evaluate the extent of their own knowledge.

- People have difficulty imagining themselves in other visceral states.

- People have difficulty projecting nonlinear trends.

- People confuse ignorance and stupidity. (Presented by Fischhoff on June 12, 2018; Fischhoff, 2013: 14036.)

The speaker then outlined five examples of simple principles of choice emerging from the research:

- People consider the return on their investment in making decisions.

- People dislike uncertainty, but can live with it.

- People are insensitive to opportunity costs.

- People are prisoners to sunk costs, hating to recognize losses.

- People may not know what they want, especially with novel questions. (Presented by Fischhoff on June 12, 2018; Fischhoff, 2013: 14036.)

Fischhoff said that, while behavior follows some simple principles, the set of principles is large, the contextual triggers are subtle, and the

interactions are complex. As a result, broad knowledge and detailed analysis are needed to develop effective interventions.

In this regard, he noted the three-step design process followed by decision science. The first step, analysis, examines what decisions people face; the second step, description, examines how people currently make decisions; and the third step, the intervention phase, assesses how they can better make decisions based on the science. He noted that this was always an iterative process that was never right the first time.

Fischhoff commented that there are many real-world cases of applying the methodology drawing on this toolkit, including radon, preterm birth, climate change, phishing, and avian influenza. These had all been done in collaboration with subject matter experts who made sure participants in the design process were working around the same problem and “kept honest.” He noted that the insights provided by previous workshops of the U.S. National Academies on gain-of-function research for pathogens with pandemic potential (NASEM, 2016; NRC, 2015) and previous work on building communication capacity to counter pandemic disease threats (NASEM, 2017b) were particularly relevant to the governance of dual use research.

Fischoff also identified three recommendations from an Institute of Medicine report on environmental justice (IOM, 1999) with implications for dual use governance: (1) improve the science base, to identify and verify environmental etiologies of disease and develop and validate research methods; (2) involve the affected populations, that is, engage with citizens from the affected populations in communities of concern, who should be actively recruited to participate in the design and execution of research; and (3) communicate findings to all stakeholders with an open, two-way process of communication.

In terms of human behavior in risk management, Fischhoff suggested there was good news because we can draw on more than a century of relevant basic science, with applications to many risks. The bad news is that, first, everyone is an intuitive behavioral scientist and has a theory about human behavior, so that actual science seems unneeded. In addition, many institutions lack not just internal expertise in behavioral research, but perhaps worse, lack what some economists call the “absorptive capacity” to obtain the needed expertise. Finally, he indicated that scientists may have perverse incentives, such as financial interests or those driven by personal interests and skills, that make them reject or ignore the insights behavioral science offers.

In terms of possible solutions, he suggested three bridging activities: the first was making relevant research available and accessible to those who would like to start a conversation; the second was creating general templates that could be adapted to local contexts; and the third was

establishing working relations that facilitate collaborative work. Fischhoff elaborated on each of these activities, beginning with making research accessible. He identified a number of sources of guidance for developing scientific communication (Fischhoff and Kadvany, 2011; Kahneman, 2011; Morgan, 2017). He also cited the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) text on communicating risks and benefits (Fischhoff et al., 2011) and the U.S. National Academy of Sciences Sackler Colloquia on the “Science of Science Communication,” which expanded the sphere of people addressing a particular topic13 and provided the basis for a major National Academies report (NASEM, 2017c).

Regarding the creation of adaptable templates as a solution, Fischhoff suggested that one approach was to develop protocols for consultative arrangements and presented an example for standard risk management processes (Fischhoff, 2015). These included a reality check at each stage, along with risk communication as a two-way process designed to make sure that people in the relevant communities were consulted and their views incorporated. He then noted work by Casman and others (2000) on the contamination of drinking water as a general model that could be applied to a variety of situations, as well as Bayesian approaches that could be used to improve the quality of the conversation even in the absence of quantitative variables (Fischhoff et al., 2006). The latter model, he suggested, could be applied to biosecurity and perhaps adapted to include differentiations among different sorts of scientists. He argued that adaptable templates could also be developed for risk-benefit communications, citing the FDA Guidance on Communicating Risks and Benefit (Fischhoff et al., 2011) as a useful source of information that summarizes the science, offers best guesses at practical implications, and shows how groups with different levels of financial resources can evaluate communications.

In terms of establishing working relations, Fischhoff presented examples of how this had been achieved in other domains, including intelligence analysis and cybersecurity, emphasizing the importance of creating a common language and drawing on an organizational model from behavioral science for these forms of collaboration (NASEM, 2017d;

___________________

13 Materials, including videos and links to related activities for the three colloquia in 2012, 2013, and 2017 may be found at National Academy of Sciences, “Arthur M. Sackler Colloquia: The Science of Science Communication.” Available at http://www.nasonline.org/programs/sackler-colloquia/completed_colloquia/science-communication.html; “Arthur M. Sackler Colloquia: The Science of Science Communication II.” Available at http://www.nasonline.org/programs/sackler-colloquia/completed_colloquia/agenda-science-communication-II.html; and “Arthur M. Sackler Colloquia: The Science of Science Communication III, Inspiring Novel Collaborations and Building Capacity.” Available at http://www.nasonline.org/programs/sackler-colloquia/completed_colloquia/Science_Communication_III.html. (accessed September 21, 2018).

NRC, 2011a). Such an organizational model requires basic familiarity with behavioral science and ongoing contact with behavioral scientists, as well as some in-house absorptive capacity.

Fischhoff concluded by discussing the FDA’s strategic plan for risk communication and template for making risk-benefit decisions (FDA, 2013), noting the template had been developed through collaborative effort in a manner that drew from the behavioral sciences and employed design principles such as stakeholder engagement. He noted that this template was used in Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use (NASEM, 2017e) and could be applied to other cases.

Discussion

The presentations stimulated a number of questions from the audience around several themes. One participant asked about the extent to which codes of conduct might stimulate cultural change beyond serving as a vehicle for transmitting messages. Huising responded that the evidence surrounding the effects of codes of conduct was mixed and that she was not familiar with any systematic research on this topic. Codes can make people feel good, which in itself may be transformative, but this was an area that requires further research.

Another participant asked whether risk perception was culturally specific and, looking beyond the focus on the United States, would risk perceptions be different elsewhere? Fischhoff responded that, generally speaking, how people think might be fairly similar across groups. However, what they believe and what matters to them likely varies much more.

Another participant asked Fischhoff about more formal risk-benefit analysis methodologies, to which he responded that risk analysis began as a design tool for looking at relative risks in circumstances where the overall safety level could not be assessed. Over time, this shifted to trying to estimate absolute levels of risk and benefit, even in situations where they cannot be meaningfully quantified.

A participant commented on the status of biosafety and EHS officers suggesting that they were not taken as seriously as academic researchers, and asked how one could increase the effectiveness of such individuals and their knowledge. Huising replied that with academic tenure came power, in contrast to others in staff roles who were apt to be ignored. However, she argued that there was scope for using knowledge and relationships with those in authority to get people to do things and exert influence in particular ways.

One workshop participant offered anecdotal evidence of his experi-

ence of top-down risk management following a workplace accident that totally changed the operation of the organization, triggering the release of resources and leadership from the highest levels that brought everyone into line. In another case, the participant outlined how he helped to address community concerns through the establishment of a citizens group with a rotating chair that allowed the community to become more closely involved in the conversation. Related to this, Huising dealt with a question about self-interest and situational reactions by drawing on her experience of group learning between the regulators and the regulated, something that, it was suggested, needs to be studied further.

This page intentionally left blank.