1

Introduction and Workshop Overview

On April 2–3, 2018, the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convened a Workshop on Examining Special Nutritional Requirements in Disease States in Washington, DC.1 As guided by the Statement of Task (see Box 1-1), the workshop had the following objectives:

- Examine pathophysiological mechanisms by which specific diseases impact nutrient metabolism and nutrition status and whether this impact would result in nutrient requirements that differ from the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs).

- Explore the role of genetic variation in nutrition requirements.

- Examine nutrient requirements in certain chronic conditions or acute phases for which emerging data suggest a contribution of nutrition status to disease outcomes. Consider the scientific evidence needed to establish such relationships and discuss principles about the relationship between nutrition requirements and specific diseases.

___________________

1 The role of the workshop’s planning committee was limited to planning the workshop, and this Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the workshop rapporteur as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

-

- Explore how a disease state impacts nutrient metabolism and nutrition status and, conversely, what is the impact of nutrition status on the disease state.

- Identify promising approaches and challenges to establishing a framework for determining special nutrient requirements related to managing disease states.

During the planning phase of the workshop, the committee gave the presenters several broad questions about the topic of special nutrient requirements to consider as they developed their presentations:

- What are the genetic basis and the related biological mechanism(s) that are disturbed in this specific disease state and how do they lead to the special nutritional requirement (or requirement for specific method of nutrient delivery)?

- How well does the genetic make-up predict what the specific nutrient needs are for this disease state? What is the evidence that there is a nutritional requirement different from that of the healthy population? (Focus on specific nutrient[s], not diet as a whole.)

- Is the disease state (or nutrition status or health-related outcomes) responsive to a specific nutritional intervention?

- What are potential complexities, including heterogeneity of responses? Why do these heterogeneities occur?

- Does a dose–response relationship exist between the nutrient and outcome of interest?

- What are the gaps in information? Are there pressing research issues?

In guiding the presenters to consider these questions in relation to their particular disease specialty, the committee hoped to generate insights that would inform the discussions about the topic as a whole. This Proceedings of a Workshop summarizes the presentations and discussions that took place over the course of the workshop.2 It is not intended to be a comprehensive summary of the topic. Furthermore, citations listed in the proceedings correspond to those presented on speakers’ slides and explicitly referred to during discussions and do not constitute a comprehensive reference list on any of the subjects covered during the workshop.

___________________

2 Materials from the workshop, including presentations and videos, can be found at http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/Nutrition/ExaminingSpecialNutritionalRequirementsinDiseaseStatesWorkshop/2018-APR-02.aspx (accessed June 14, 2018).

ORGANIZATION OF THIS PROCEEDINGS OF A WORKSHOP

The organization of this Proceedings of a Workshop parallels the workshop agenda. This chapter provides an overview of the objectives and scope of the workshop, along with welcoming and opening remarks. Speakers during this session also provided some background and context for later sessions by defining special nutrient requirements and describing underlying biological processes of special nutrient requirements. Chapter 2 summarizes Session 2 presentations and discussions. Speakers discussed nutrient needs due to loss of function in several genetic diseases, including phenylketonuria (PKU) hydroxylase deficiency, mitochondrial-associated metabolic disorders, and complex inborn errors of metabolism. Chapter 3 summarizes Session 3 presentations, which looked at nutrient needs resulting from disease-induced loss of function. Speakers discussed intestinal failure, cystic fibrosis, inflammatory bowel disease, blood–brain barrier dysfunction, and chronic kidney disease. Chapter 4 summarizes Session 4 presentations on disease-induced nutrient deficiencies and conditionally essential nutrients. The session focused on arginine in sickle cell anemia, potential nutrient needs in traumatic brain injury, and metabolic turnover, inflammation, and redistribution. This session was also to have included a presentation on nutrient needs in burns, cachexia, and surgery, but the presenter, Paul Wischmeyer of Duke University School of Medicine, was unable to participate. Chapter 5 summarizes Session 5 presentations, which considered a range of research issues that are relevant to building the evidence base in this area. Speakers discussed inflammatory bowel disease and cancer as illustrative examples. Chapter 6 summarizes the final session, in which a panel of presenters and participants were invited to reflect on themes and principles that emerged during the workshop and to discuss potential opportunities for progress in this area. The workshop closed with remarks by a speaker from each of the workshop sponsors. The speakers expressed their appreciation for the thoughtful presentations and discussions and highlighted key themes from the workshop that echo their own missions and initiatives. The workshop agenda is presented in Appendix A. Biographical sketches of the speakers and moderators are presented in Appendix B.

WELCOMING REMARKS

Barbara Schneeman, Professor Emerita, University of California, Davis, and chair of the Planning Committee, opened the workshop by providing background and insight on the origins of the workshop and the planning committee’s approach to developing the agenda. She began

by highlighting several key sentences from the Statement of Task, which captured the essence of the workshop’s intent: The task is to convene a public workshop to explore the evidence for special nutritional requirements in disease states and medical conditions that cannot be met with normal diet. The workshop will review the currently available evidence used to determine potential nutritional requirements that are not encompassed within the normal population variation.

Schneeman then reviewed the five questions in the Statement of Task and pointed out that the Statement of Task did not cover medical foods. Medical foods are under the purview of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which has provided guidance on the criteria that are necessary for a product to be considered a medical food. The focus of this workshop, she emphasized, was on special nutrient requirements that would not be met through normal diets. Schneeman also noted that health claims, nutrient content claims, and structure and function claims attached to foods for the general population were not part of the workshop’s task.

Schneeman then reviewed the workshop objectives, putting them in the context of related National Academies work, including the DRI reports, the 2017 consensus study report Guiding Principles for Developing Dietary Reference Intakes Based on Chronic Disease (NASEM, 2017a) and the 2018 proceedings Nutrigenomics and the Future of Nutrition: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief (NASEM, 2018).

Finally, Schneeman referred participants to the National Academies’ report Redesigning the Process for Establishing the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (NASEM, 2017b). She noted that this report acknowledged that the Dietary Guidelines for Americans cover the general population, which may include individuals with certain types of chronic disease. All these reports together, she said, provide a useful framework for understanding the current thinking about nutrition for the general population. One of the questions left unresolved, however, Schneeman felt, is the role of nutrition in managing disease, which the current workshop would begin to explore.

With that context, Schneeman introduced the two speakers for this session. Patsy Brannon, Professor, Division of Nutritional Sciences, Cornell University, set the stage by providing an overview of DRIs and how special nutrient requirements might differ from them. Patrick Stover, Vice Chancellor and Dean for Agriculture and Life Sciences at Texas A&M AgriLife, discussed the underlying biological processes of special nutritional requirements, with a focus on biomarkers.

WHAT DEFINES A SPECIAL NUTRITIONAL REQUIREMENT?3

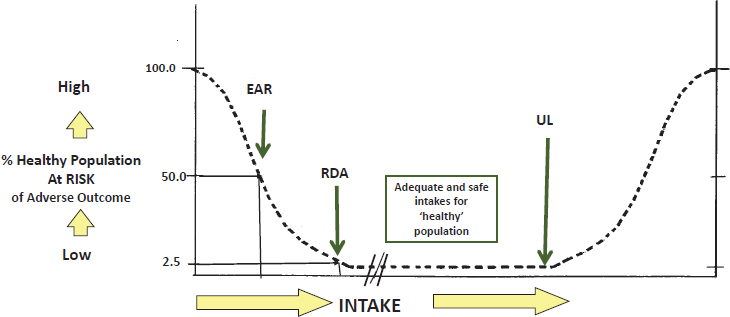

The traditional DRIs reflect a distribution of requirements and risk of adverse outcomes in a healthy population4 (see Figure 1-1), although questions and controversies exist about what constitutes healthy when the general population contains a substantive prevalence of chronic disease. In this distribution, Brannon explained, the risk of adverse outcomes increases when intakes are too low or too high. The Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) is defined as the intake that meets the needs of 50 percent of the population, and the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) is defined as a level of intake that, if consumed on a chronic basis, may lead to adverse outcomes. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) is set to meet the needs of 97.5 percent of the population.

Within this framework, intakes at or above the RDA and below the UL constitute an adequate and safe intake for healthy populations. Brannon noted that another way of looking at this distribution is the U-shaped curve nested within the distribution, which shows the EAR. Brannon then explained that the current process for setting DRIs occurs within a risk assessment framework. The first step is to identify one or more health outcome(s) related to consumption of a specific nutrient; causality is important in this relationship. Once a health outcome(s) is identified, the next step is to assess the dose–response association in order to set the reference value. Additional steps in the DRI process are to examine the assessment of intakes in the population and to characterize risk at various levels of intake.

Identifying Health Outcomes

Beginning in 1997, Brannon stated, the usual health outcome for DRIs was nutrient deficiency diseases, and most of the DRIs were set to prevent deficiency. Chronic disease endpoints were considered in setting DRIs for two nutrients—fiber and vitamin D. In 2011, beginning with vitamin D and calcium, DRI committees began to incorporate systematic reviews into their work. Regardless of the nutrient under consideration, DRI committees face a number of challenges in conducting these systematic reviews, including

- selecting outcomes with the greatest value; which may be a challenge of particular importance for special nutrient requirements because the health outcome for a specific disease population may differ from that of the healthy population;

___________________

3 This section summarizes information presented by Patsy Brannon.

4 For DRI values, see http://nationalacademies.org/HMD/Activities/Nutrition/SummaryDRIs/DRI-Tables.aspx (accessed June 6, 2018).

NOTE: DRI = Dietary Reference Intake; EAR = Estimated Average Requirement; RDA = Recommended Dietary Allowance; UL = Tolerable Upper Intake Level.

SOURCE: As presented by Patsy Brannon, April 2, 2018.

- identifying which outcomes, designs, populations, and other factors are of limited value;

- minimizing the differences in priorities and outlooks of the various members of the systematic review technical expert panel, which may affect decisions about the outcomes chosen;

- establishing instructions on weighing outcomes to eliminate variability; and

- selecting tools (e.g., evidence maps) to facilitate decision making.

The EAR and the RDA are usually based on the same health outcome because the EAR is specified, if possible, and then the RDA is set at two standard deviations above the EAR. When the existing evidence does not allow for the establishment of an EAR, an Adequate Intake (AI) is established. It is not certain as to how the AI relates to the distribution of the requirement, but it generally meets the needs of most of the population. The UL is often based on a different health outcome than the EAR and the RDA. Compared to the EARs and RDAs, a more cautious approach is taken in looking at the evidence for establishing ULs because randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are not typically conducted to identify toxicity health outcomes and, therefore, causality can be difficult to establish.

Nutritional Kinetics, Dynamics, and Requirements

Brannon noted that when nutrients are consumed, kinetic and dynamic processes occur that result in nutrient concentration at a site of action. At a minimum, the kinetic processes include absorption, which includes digestion and bioavailability, distribution in terms of the volume and the compartments in which the nutrient is distributed, metabolism, and excretion. The dynamic processes include actions, including toxicological actions, of the nutrient at a site in the body. These relate to dose response and effect, maximal efficacy, and the temporal response. Individuals vary in these kinetic and dynamic processes because of a number of factors, including genetics, epigenetics, age, sex, the physiological state (e.g., whether the individual is growing, pregnant, lactating), nutrient–diet interactions, nutrient–environment interactions, and drug–nutrient interactions. With this context, Brannon then noted that disease state is a critical factor that can affect the kinetics and dynamics of nutritional requirements. The following are several examples of how the nutritional requirements of several disease populations might differ from the distribution of nutrient need in a generally healthy population:

- Because of an alteration in phenylalanine metabolism, individuals with PKU may have a lower UL for ingestion of phenylalanine, relative to the distribution in a healthy population.

- Because of an impairment in digestion, most individuals with cystic fibrosis have an increased need for fat-soluble vitamins.

Special nutrition requirements can be thought of as a distribution of nutritional requirements for a specific disease population outside of the DRI distribution for healthy populations (see Box 1-2). The evidence needed to determine whether this difference exists would need to consider the following factors:

- The mechanism for the altered requirement. Is it kinetic, dynamic, system wide, tissue specific, or some combination thereof?

- Biomarkers of effect. What are the challenges of using biomarkers? Are systemic biomarkers or specific tissue biomarkers needed?

Brannon noted that the first step in setting DRIs—identifying the health outcome—helps determine whether the focus should be on management or nutritional treatment of the disease. The second step—determining dose–response—allows for a comparison to the DRI distribution for generally healthy populations so that a difference (if one exists) can be demonstrated.

Brannon closed her remarks by stating that a particular challenge in the DRI-setting process is determining how to compare the distribution of a dose response for a special nutritional requirement if the health outcome for that disease population is a different health outcome than for the generally healthy population. She expressed the hope that workshop discussions would shed light on this issue.

THE UNDERLYING BIOLOGICAL PROCESSES OF SPECIAL NUTRITIONAL REQUIREMENTS5

A central question that has been asked for years when considering recommendations about dietary and nutrient adequacy is adequate for what? The discussion around this question, Stover said, has evolved over time from an emphasis on avoiding deficiency to an emphasis on chronic disease prevention. The workshop’s focus has taken this discussion a step further by considering disease management.

Stover then noted that the recent reports from the National Academies on the redesign process for the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (NASEM, 2017b) and the development of DRIs based on chronic diseases (NASEM, 2017a) are an acknowledgment that dietary recommendations must now cover highly diverse populations, including those with chronic diseases and challenges to metabolic health. A systems perspective must be brought to bear when thinking about dietary requirements in the context of disease prevention and management. This systems orientation, explained Stover, requires a rethinking of biomarkers as integrative biomarkers that capture the interactions of all the nutrients within the system and all the other inherent biological factors, such as genetic variation. Furthermore, if aging is a risk factor for chronic disease, then investigators need to understand the biomarkers of aging and how nutrition or nutrient supply alters the aging trajectory toward health or disease.

Stover also noted that the committee for DRIs in chronic disease (NASEM, 2017a) established that any recommendation based on a chronic disease endpoint should have a moderate level of evidence using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system. He stated that this level of evidence sets a very high bar for the nutrition community, and that it exists for very few nutrient and chronic disease relationships.

Modifiers of Nutrient and Food Needs

The amount of nutrients required by an individual is determined by a number of physiological processes, including absorption, catabolism, excretion, metabolism, stability, transport, bio-activation, energetic state, and nutrient storage. Stover stated that all of these biological processes have modifiers and sensitizers, such as sex, pregnancy, lactation, age, the microbiome, pharmaceuticals, toxins, nutrient–nutrient interactions, genetics, food matrix, and epigenetics. All of these factors influence the physiological processes that determine nutrient needs and provide varia-

___________________

5 This section summarizes information presented by Patrick Stover.

tions in requirements in the population. Disease can also be a major modifier of these processes.

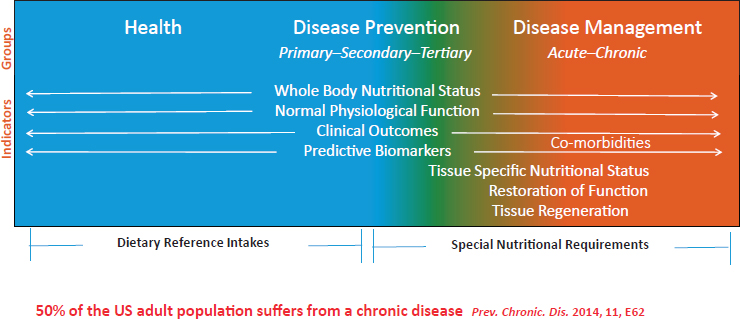

Stover then illustrated current thinking about nutrient requirements for different populations (see Figure 1-2). For health and disease prevention, the DRIs capture the level of intake that is required to maintain whole body nutritional status, normal physiological function, or clinical outcomes in healthy people. Predictive biomarkers can be useful in determining nutrients that are needed currently and their effect on the risk, or onset, of chronic disease in the future. Recent estimates show that about half of the U.S. population suffers from, and is being treated for, a chronic disease (Ward et al., 2014). Based on this, Stover suggested that the DRIs may not be suitable for 50 percent of the U.S. population. Therefore, how should nutrient requirements in disease management be considered? For example, evidence may suggest that some of the comorbidities associated with a disease are due to the effect of that disease on nutritional status or nutritional function, which then increases susceptibility to other diseases. Diabetic neuropathy is a comorbidity that may be due to some sort of a nutrient deficiency related to the diabetes, Stover noted.

Tissue-specific nutritional status is also relevant. Sometimes, a disease is isolated to a single tissue and measuring and quantifying the nutritional needs of that diseased tissue in the absence of whole body indicators of the effect of a nutritional deficiency or nutritional excess can present a formidable challenge. Another issue in determining nutrient needs in a disease state is restoration of function that requires conditionally essential nutrients and tissue regeneration. A final consideration is that special nutritional requirements may optimize the number of stem cells avail-

SOURCE: As presented by Patrick Stover, April 2, 2018.

able, the quality of those stem cells, and their ability to restore an organ in terms of both the number of cells and their function.

Drugs, Nutrient Levels, and Biomarkers

Stover then noted that the effects of drugs on nutrient levels and their biomarkers need to be better understood and considered. Some examples are the effect of anti-hypertensives on folate levels; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin on vitamin C and iron; hypoglycemics on vitamin B12, calcium, and vitamin D; and acid-suppressing drugs (proton pump inhibitors) on vitamin B12, vitamin C, iron, calcium, magnesium, and zinc.

Because fulfilling special nutritional needs is not equivalent to treating a primary disease, a relevant question is whether a nutrient intervention to respond to that special requirement may have a physiological or drug (i.e., an off-target) effect. Stover suggested that special nutritional needs act through evolutionarily derived physiological mechanisms to restore nutritional adequacy and physiological function, thereby managing a specific disease state, not through off-target effects. Niacin is an example of a nutrient that at pharmacological doses (i.e., 10 times the DRI6) improves lipid profiles, and it is not given because of a niacin deficiency. Therefore, niacin is not a special nutritional need but it is having an off-target effect that results in clinical improvement. Stover then set out the following considerations for proposed standards for special nutritional needs:

- A robust biological premise must be established. How and why are the nutritional needs different? What are the relevant biomarkers of these altered nutrient needs? Is it possible to use the same biomarkers for populations with a disease that are used with healthy populations?

- Efficacy must be addressed. Does the increased or decreased intake address disease-induced changes in nutrient needs? Does it affect nutritional status and/or nutrient function? Moreover, are these effects chronic or acute? Does the altered intake address any of the symptoms of the primary disease resulting from the nutritional deficiency and/or any comorbidities that are secondary to the primary disease, but that act through nutrition?

- Classification must be considered. What is the heterogeneity around nutritional requirements for any given disease or disease subtype?

___________________

6 For DRI values, see http://nationalacademies.org/HMD/Activities/Nutrition/SummaryDRIs/DRI-Tables.aspx (accessed June 6, 2018).

All of the factors involved in disease-related etiology (e.g., inflammation in combination with genetic predisposition, autoimmunity, mitochondrial dysfunction, pharmaceuticals, and trauma) can influence physiological processes related to nutrition. Absorption, transport across the brain or nerve barriers, catabolism of nutrients, excretion of nutrients, altered metabolism, and altered distribution of nutrients among tissues can all be affected by a disease process and they affect human nutrition in terms of causing whole body deficiencies, tissue-specific deficiencies, and nutrient toxicities. These processes can also affect both the function and the status of biomarkers. Tissue-specific biomarkers of nutrient deficiency therefore become valuable ways to assess nutritional status. Predictive biomarkers that can reflect depleted nutrients and disease, progression of a disease, or progression of comorbidities related to that disease will all be needed, said Stover. An example of the complexities involved in factors that affect nutrient status and/or biomarkers of disease is acquired arginine deficiency syndrome, in which the enzyme arginase that degrades arginine is elevated. Infection, which results in tissue redistribution or excretion of nutrients such as iron, is another example.

Stover noted that a number of workshop speakers would address inborn errors of metabolism. These conditions, where nutrition compensates for functional deficits caused by genetics, may be a good model for considering nutrition in chronic disease. In the context of chronic disease, it may be possible to think about nutrition compensating for functional deficits caused by the disease.

The Cochrane PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparisons, Outcomes) approach provides a way to think about this, suggested Stover. Each of the PICO elements can be seen through the DRI or special nutritional needs lens (see Table 1-1).

Stover closed his presentation by noting that special nutritional requirements are an important area of research. When the American Society for Nutrition published its research agenda in 2013, it listed variability in responses to diet and medical management as two of its six research priority areas (ASN, 2013). The USA Interagency Committee on Human Nutrition Research included “How do we enhance our understanding of the role of nutrition in health promotion and disease prevention and treatment?” as the first question in its National Nutrition Research Roadmap 2016–2021 (ICHNR, 2016). Its second question was “How do we enhance our understanding of individual differences in nutritional status and variability in response to diet?”

TABLE 1-1 Comparison of Dietary Reference Intakes and Special Nutritional Needs

| DRI | Special Nutritional Needs | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Healthy populations Sex, age, pregnancy, lactation | Clinical populations Classifiable condition/disease |

| Intervention | Diet, dietary supplement | Needs may not be met by “diet” alone |

| Comparisons | Dose response | Dose response |

| Outcomes | Avoid nutrient deficiency, support physiological processes, and/or chronic disease prevention | Avoid disease-induced nutrient deficiency, support compromised physiological processes in disease and/or support tissue regeneration (dietary management of disease) |

NOTE: DRI = Dietary Reference Intake.

SOURCE: As presented by Patrick Stover, April 2, 2018.

MODERATED PANEL DISCUSSION AND Q&A

In the discussion period following the Brannon and Stover presentations, participants addressed a variety of topics.

Characterizing Nutrients

The discussion highlighted the fact that the definition of a “nutrient” might be too narrow and panelists agree that using the broader term “nutrient and other food substance,” as in the recent National Academies report on setting DRIs in chronic diseases (NASEM, 2017a) will be more helpful. Brannon envisioned a scenario in which a disease affects nutritional requirements or metabolism such that a bioactive food component might have an important role to play in managing those effects and it could influence nutrient distributions and other factors.

Virginia Stallings, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, followed up by suggesting the related idea of a special dietary pattern that could influence the response of nutrients because of small, synergistic effects with bioactive food components.

Lessons from Research in Aging

Stover noted that investigators have shown that as people age, their epigenetic profiles decay. This decay results in more randomness in gene expression, which leads to functional decay in networks. Observational studies in aging populations show a correlation between the rate of decay

of gene expression patterns or epigenetic landscape and the risk of chronic disease. Those whose epigenetic patterns decay more rapidly tend to have chronic diseases. Those who are able to retain earlier epigenetic signatures and gene expression profiles tend to age much more healthily. They have a lower biological age than their chronological age.

Stover continued that the role of nutrition in this environment is of considerable interest now. It is known that nutrition is essential in establishing embryonic epigenetic landscapes and work in fetal origins of disease suggests that what the mother eats affects what her child’s epigenetic patterns will be. What is not known, he said, is whether nutrition can be used to reprogram stem cells so that they can repopulate an aging organ with a younger gene expression pattern that could lead to metrics with improved function.

Nutrients and Bioactive Food Components

Schneeman commented that, although fiber is not considered a nutrient, a DRI was established for a fiber AI based on disease risk reduction. She also thought that Stover’s discussion of comorbidities, and the notion that they should be managed as part of the disease process, was a new and thought-provoking notion.

An attendee asked Brannon and Stover to comment on other functional substances derived from foods. These substances may not have DRIs but are known to have an effect on biomarkers. For example, whey protein is concentrated with transforming growth factor beta. Oral immunoglobulin formulations have been tested since 1972 for infectious neuropathy, inflammatory bowel disease, or even irritable bowel syndrome. Some probiotic formulations can help in managing a disease when they are combined.

Stover agreed that this question raises the intriguing issue of what a nutrient is and how to consider combinations of nutrients. It may not be possible to meet special nutritional requirements by diet alone. In that case, nutrient formulations must be carefully considered. Stover also noted that any consideration of the gut must include the microbiome. The connection between nutrition, gut health, and overall physiological health will not be fully understood until interactions with the microbiome are studied further.

Use of Biomarkers

On a participant’s question related to the clinical implications of identifying and using biomarkers to improve nutritional management of disease states, Brannon responded that she is not aware of much work

that links physical exams either by a physician or another health care practitioner or registered dietician nutritionist with special nutritional requirements. She suggested that continued work in this area will be part of the translational research that might be necessary to make progress. She agreed that integrating validated biomarkers or surrogate endpoints into clinical practice and diagnosis will be difficult.

Schneeman added that one of the critical needs in this area, and in nutrition generally, is the importance of validated biomarkers. For a regulatory process, she stated that it is particularly important that those biomarkers be validated as surrogate endpoints.

Levels of Evidence

The suggestion that at least a moderate grade of evidence is necessary for meaningful recommendations to inform clinical practice was discussed as an issue of particular importance in nutrition science because few large RCTs are available to inform this work, and the lack of convincing evidence is a concern. Brannon noted that, in her opinion, a need for moderate strength of evidence does not necessarily equate to conducting many RCTs but can be generated with congruent and consistent effects integrated across observational studies and RCTs. She added that one reason for recommending at least a moderate strength of evidence is that it is currently difficult to make policy on a lesser grade of evidence. Reflecting from his experience on the DRI and chronic disease committee, Stover added that the GRADE framework is the standard for evaluating medical data and making recommendations and, if the goal is to connect diet to health, a high standard of evidence is needed. Schneeman added that she serves on the World Health Organization (WHO) Nutrition Guidance Expert Advisory Group, which uses the GRADE system for evaluating evidence. She stated that WHO recognizes that grading the strength of the evidence is just one step in the process. Another critical element, she states, is the strength of the recommendation that can be made based on that evidence.

Translation to the Clinical Setting

Concerns were raised regarding the translation of special nutritional requirements to patients when a regulatory path currently does not exist to get that treatment to patients. Susan Berry, University of Minnesota, replied that this situation is very common in inherited metabolic diseases. Some in the field, she said, had misgivings about arginine becoming a drug because of the difficulties in setting up appropriate studies when the number of patients available is limited. This makes it very difficult to achieve an important but very high standard in nutritional requirements.

Schneeman added that in the current regulatory framework a statement that a compound will treat, cure, prevent, or manage disease makes that compound a drug or a medical device. To provide an alternative, the Orphan Drug Act created a category called medical foods. A 1996 Federal Register notice outlined FDA’s thinking about what constituted a medical food and foods for special dietary uses, but the notice was eventually withdrawn and an approval process for medical foods does not currently exist. A manufacturer can declare a product to be a medical food, and if FDA does not agree with this determination, the agency may send a warning letter. Schneeman concluded by saying that if the concept of special nutrient requirements can be defined and is relevant to the criteria for medical foods, a framework is necessary that will allow the public to have confidence in the claims being made.

Personalized Nutrition

A question was raised about the use of technological innovation to meet individual needs of certain patients. Stover responded first, saying that disruptive technologies are likely to play an important role in the future. For example, the same paper microfluidic device that enables pregnancy tests is now being commercialized with chronic disease markers, nutritional status markers, and other markers. Individuals will have considerable personal data and will be able to get real-time readouts of their physiological status and disease status. Schneeman agreed, stating that advances in genetics and metabolomics will help to define smaller populations where unique or special nutrient needs can be examined and where personalized nutrition can be defined in a way that is meaningful to individuals.

REFERENCES

ASN (American Society for Nutrition). 2013. The American Society for Nutrition announces nutrition research needs and a statement on fiber: 6 nutrition research areas with greatest opportunity for health impact. Nutrition Today 48(5):189–190.

ICHNR (Interagency Committee on Human Nutrition Research). 2016. National nutrition research roadmap 2016–2021: Advancing nutrition research to improve and sustain health. Washington, DC: Interagency Committee on Human Nutrition Research.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2017a. Guiding principles for developing Dietary Reference Intakes based on chronic disease. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2017b. Redesigning the process for establishing the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2018. Nutrigenomics and the future of nutrition. Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Ward, B. W., J. S. Schiller, and R. A. Goodman. 2014. Multiple chronic conditions among US adults: A 2012 update. Preventing Chronic Disease 11:E62.

This page intentionally left blank.