6

The Private Sector and Planetary Protection Policy Development

PRIVATE-SECTOR SPACE ACTIVITIES AND PLANETARY PROTECTION

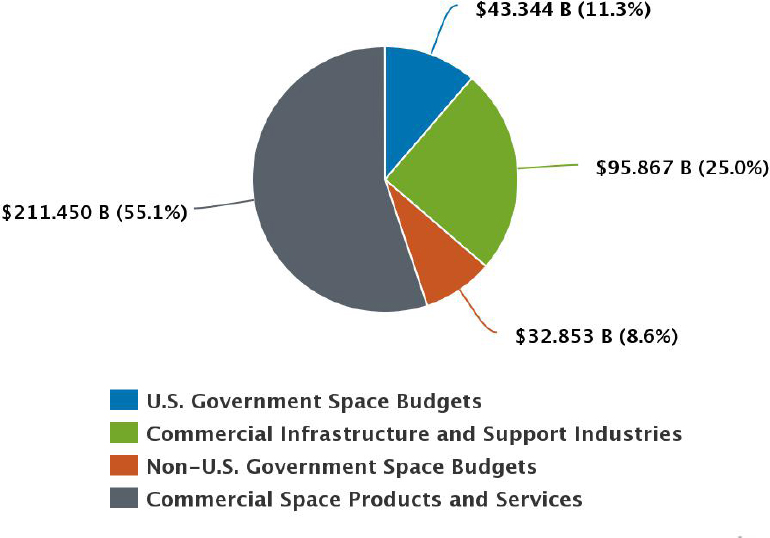

Private-sector enterprises have long been involved in space activities, such as launching and operating communication satellites.1 Today, private-sector work with communications satellites and their associated distribution networks account for approximately 80 percent of the more than $375 billion global space economy (see Figure 6.1).2 Traditional private-sector space activities, such as launching and operating communications satellites, do not generate planetary protection concerns. As noted in Chapter 3, this fact helps explain the lack of private-sector involvement in planetary protection policy development processes, such as those of the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR).

In addition, the committee noted the emergence of private-sector interest in new types of space activities, which fall within what is variously called “space entrepreneurship” and “new space.” These new activities include delivering crew and cargo to the International Space Station, launching and operating remote sensing technologies, plans for asteroid mining, interest in space tourism, transport to the lunar surface, and missions to Mars. The only “new space” areas that implicate serious planetary protection concerns are missions to Mars.3

___________________

1 In the 2010 National Space Policy, “commercial space” activities involve “space goods, services, or activities provided by private sector enterprises that bear a reasonable portion of the investment risk and responsibility for the activity, operate in accordance with typical market-based incentives for controlling cost and optimizing return on investment, and have the legal capacity to offer these goods or services to existing or potential nongovernmental customers.” Executive Office of the President, National Space Policy of the United States of America, June 28, 2010, p. 10. https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/national_space_policy_6-28-10.pdf.

2 The Space Foundation, The Space Report 2017, https://www.thespacereport.org/year/2017.

3 Some “new space” activities, such as missions to the lunar surface, would have to satisfy procedural planetary protection requirements (e.g., documentation and inventory of organics), such as being assigned a category (e.g., Category II, mission to the Moon), but, once these procedural obligations are met, the activities would not have to comply with any substantive planetary protection requirements. Returning extraterrestrial materials to Earth may potentially cause planetary protection concerns. Samples returned from the Moon are classified as unrestricted Earth return. Current COSPAR policy for the return of samples from asteroids, comets, and other small solar system bodies requires determination as to whether a mission is classified as restricted or unrestricted Earth return. This determination “shall be undertaken with respect to the best multidisciplinary scientific advice, using the framework presented in the 1998 report of the US National Research Council’s Space Studies Board entitled, Evaluating the Biological Potential in Samples Returned from Planetary Satellites and Small Solar System Bodies: Framework for Decision Making.” It is conceivable that the referenced framework could trigger a determination of restricted Earth return for certain organic- or water-rich small bodies. The martian moons, Phobos and Deimos, are currently a gray area with respect to their sample-return categorization. This uncertainty is currently being addressed by parallel studies sponsored by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency and by NASA and the European Space Agency.

Finding: Current planetary protection policy and requirements do not mandate significant actions beyond documentation and inventory of organic materials for the vast majority of ongoing and planned private-sector space activities.

In connection with missions to Mars, Chapter 5 noted that at least two major companies have expressed interest in and described plans to send their own robotic and/or human missions to Mars. The planetary protection challenges that robotic and human missions to Mars would create also arise with the development and execution of plans for private-sector missions to Mars.

Recommendation 6.1: Planetary protection policies and requirements for forward and back contamination should apply equally to both government-sponsored and private-sector missions to Mars.

The possibility of private-sector missions to Mars creates two planetary protection policy issues requiring attention by the policy development process: (1) the so-called “regulatory gap” in federal law; and (2) the participation of the private sector in the development of planetary protection policy.

PLANETARY PROTECTION, THE PRIVATE SECTOR, AND THE REGULATORY GAP

No federal regulatory agency has the jurisdiction to authorize and continually supervise on-orbit activities undertaken by private-sector entities, including activities that could raise planetary protection issues.4 The com-

___________________

4 See, for example, Subcommittee on Space of the Committee on Science, Space and Technology, U.S. House of Representatives, Hearings on Space Traffic Management: How to Prevent a Real Life “Gravity,” May 9, 2014, https://science.house.gov/legislation/hearings/space-subcommittee-hearing-space-traffic-management-how-prevent-real-life; and Hearings on Exploring Our Solar System: The ASTEROIDS Act as a Key Step, September 10, 2014, https://science.house.gov/legislation/hearings/subcommittee-space-exploring-our-solar-system-asteroids-act-key-step.

mittee heard from numerous experts that this regulatory gap is a serious problem in U.S. space law.5 Despite legislative and executive branch attention to this issue, Congress has not, to date, eliminated the regulatory gap.6 Addressing this gap is a necessary prerequisite to the development and implementation of an effective planetary protection policy applicable to private-sector entities. As a current example of this concern, on February 6, 2018, SpaceX conducted a test launch of its new Falcon 9 Heavy vehicle in which the dummy payload (i.e., a used Tesla roadster) was boosted into a Mars-crossing orbit. Only after the initial release of this report was it revealed that formal, but limited, consultations on the launch’s planetary protection implications took place between the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), NASA, and SpaceX (Appendix H).7

In 2015, Congress required a report from the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) on how the United States could authorize and continually supervise private sector on-orbit activities to meet its Outer Space Treaty (OST) obligations.8 OSTP proposed legislation under which Congress would authorize the Department of Transportation to grant authorizations for private-sector space missions. In exercising this authority, the Secretary of Transportation would be advised by “an interagency process in which designated agencies would review a proposed mission in relation to specified government interests, with only such conditions as necessary for fulfillment of those government interests.”9

For private-sector space activities that raise planetary protection issues, such as robotic or human missions to Mars, the regulatory gap creates concerns under the OST. The treaty requires the United States to authorize and continuously supervise the space activities of nongovernmental entities,10 including activities that create potential forward or backward contamination risks. This obligation also requires the United States to “adopt appropriate measures” for planetary protection purposes.11 Thus, government and private space activities are required to meet equivalent standards and perform in equivalent ways under the treaty’s planetary protection obligations. In addition to legal authority, the agency given this jurisdiction will require relevant technical and scientific expertise or access to such expertise.

NASA is not a regulatory agency and, therefore, cannot authorize and continually supervise private-sector space activities. However, NASA is where the federal government’s expertise on planetary protection resides. Possible regulatory agencies, such as the Department of Commerce or the Department of Transportation, have the competency to regulate private-sector space activities. However, they do not have the necessary scientific and technical expertise to guide the development of regulations on planetary protection for the private sector. Any approach to eliminating the regulatory gap needs to ensure that the expertise NASA uses to address planetary protection informs the exercise of regulatory authority. One model for achieving this goal is the memorandum of

___________________

5 Other bodies of federal law that apply to private-sector space activities, such as export control regulations, do not address the regulatory gap with respect to planetary protection. Export control regulations have raised issues with, for example, private-sector launching and operation of satellites and remote sensing technologies. However, these space activities do not involve planetary protection concerns. For export control regulations, see International Traffic in Arms Regulations, 22 CFR Parts 120-130 (implemented by the Department of State), and Export Administration Regulations, 22 CFR Parts 730-774 (implemented by the Department of Commerce).

6 The “regulatory gap” affects other private-sector space activities that do not necessarily implicate planetary protection, such as lunar missions and asteroid mining. In reviewing private-sector plans for lunar missions, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) tested the scope of its regulatory authority, leading it to conclude that the FAA might need additional authority to evaluate future missions in order to ensure the United States complies with the OST. See, for example, FAA, Fact Sheet—Moon Express Payload Review Determination, August 3, 2016, https://www.faa.gov/news/fact_sheets/news_story.cfm?newsId=20595.

7 I. Klotz, Launch of Tesla casts U.S. policy into new legal regime, Aviation Week and Space Technology, February 15, 2018, http://aviationweek.com/commercializing-space/launch-tesla-casts-us-policy-new-legal-regime.

8 U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, P.L. 114-90. (2015), Section 108.

9 Executive Office of the President, Office of Science Technology Policy, Report submitted in fulfillment of a requirement contained in the U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, April 4, 2016 (“Section 108 Report”), https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/csla_report_4-4-16_final.pdf.

10 Outer Space Treaty, Article VI (“The activities of non-governmental entities in outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, shall require authorization and continuing supervision by the appropriate State Party to the Treaty.”).

11 Outer Space Treaty, Article IX.

understanding NASA and the FAA entered to “avoid conflicting requirements and multiple sets of standards [and to] exchange knowledge and best practices” in the context of commercial transport of passengers to low Earth orbit.12

Although Congress has not yet enacted the necessary legislation, it could resolve the regulatory gap in different ways. It could empower a single agency to regulate private-sector space activities that raise planetary protection concerns. Congress could also adopt the approach recommended by the OSTP—provide a federal regulatory agency with authority over private-sector space missions, the exercise of which is informed by an interagency process.13,14 Whatever approach Congress adopts to close the regulatory gap would benefit from the inclusion of mechanisms helping the private sector become familiar with expected authorization processes and associated timelines.

Finding: A regulatory gap exists in U.S. federal law and poses a problem for U.S. compliance with the OST’s obligations on planetary protection with regard to private sector enterprises. The OST requires states parties, including the United States, to authorize and continually supervise nongovernmental entities, including private sector enterprises, for any space activity that implicates the treaty, including its planetary protection provisions.

Recommendation 6.2: Congress should address the regulatory gap by promulgating legislation that grants jurisdiction to an appropriate federal regulatory agency to authorize and supervise private-sector space activities that raise planetary protection issues. The legislation should also ensure that the authority granted be exercised in a way that is based upon the most relevant scientific information and best practices on planetary protection.

PRIVATE-SECTOR PARTICIPATION IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF PLANETARY PROTECTION POLICY

The need to fill the regulatory gap and apply planetary protection policy equally to government-sponsored and private-sector missions highlights issues related to the participation of the private-sector in making planetary protection policy. Historically, the private sector has not been involved in the development of planetary protection policy because the space activities pursued by companies have not generated concerns with forward or backward contamination. However, the interest of some private-sector enterprises in missions to Mars generates questions about private-sector participation in planetary policy development. The vibrancy and innovation associated with “new space” activities suggest that private-sector interest in missions to Mars might increase as NASA moves its Mars projects forward, and as the Falcon 9 Heavy launch on February 2018 has demonstrated, at least one private entity has the wherewithal to send an object to Mars.

On the one hand, the committee has identified only two companies that space exploration experts presently consider potentially serious players in missions to Mars. Even with these two companies, doubts exist whether they will be able to mount their own missions to Mars, as opposed to providing goods and services to government-sponsored missions. Creating new participation rights or mechanisms for the private sector in terms of planetary protection policy development on this basis could be perceived as granting special treatment for specific enterprises.

___________________

12 2012 Memorandum of Understanding Between the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) for Achievement of Mutual Goals in Human Space Transportation, https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/files/NASA-FAAMOU_signed.pdf.

13 In February 2018, the reestablished National Space Council recommended that the Department of Commerce take the lead in regulating private-sector space activities (See https://spacepolicyonline.com/news/second-national-space-council-meeting-focuses-on-regulatory-reformchina). In April 2018, the House of Representatives passed H.R. 2809, the American Space Commerce Free Enterprise Act, which designates the Department of Commerce as the federal agency responsible for the authorization and supervision of private-sector space activities called for in Article VI of the OST. However, H.R. 2809 retains the licensing roles of the FAA (for launch and reentry) and Federal Communications Commission (for space communications) will retain their traditional roles in licensing launch/reentry and space communications, respectively. For more information about H.R. 2809, see https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/2809). To date, the Senate has not acted on this or any related bill.

14 In late May 2018, President Trump signed Space Policy Directive 2 and thereby initiated a process to streamline regulations on the commercial use of space as recommended by the National Space Council in February 2018. For more details see https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/space-policy-directive-2-streamlining-regulations-commercial-use-space.

On the other hand, the private sector already participates in making space policy. NASA directly engages with the private sector on various space issues, and companies can communicate with members of Congress on legislation, the White House on policy, and federal agencies on regulations affecting their space activities.15

At the international level, COSPAR has long been open to the participation of representatives from the private sector. COSPAR permits officials or staff from companies to attend its colloquia, workshops, symposia, assemblies, and policy-making deliberations. COSPAR allows industry representatives to have the same membership status as scientists. Despite its openness to commercial participation, not many companies have been involved in COSPAR activities on planetary protection. Few firms have taken out Associated Supporter status,16 and few individuals working in the private sector appear within the ranks of COSPAR associates.17 The lack of private-sector participation in COSPAR’s planetary protection policy development primarily exists because, to date, companies have not pursued space activities that implicate planetary protection.18

This pattern might change if commercial interest in Mars increases in the coming years, but, at the moment, there is little evidence of such a change. COSPAR officials told the committee they would like to increase private-sector participation in COSPAR’s planetary protection policy development processes. One option for COSPAR to expand such participation would be to partner with an organization having a larger level of private-sector participation, such as the International Astronautical Federation (IAF). Past joint COSPAR-IAF congresses have not been especially effective at promoting substantial cross-organizational interactions.19 Another option is for COSPAR and other interested parties to sponsor special sessions on planetary protection issues at the annual IAF-organized International Astronautical Congress.20 Nevertheless, with sufficient motivation by all the players, such a partnership might enhance how the COSPAR process reflects private-sector input on the science informing planetary protection policy and facilitate private-sector commitment to complying with planetary protection guidance from COSPAR.

Finding: To date, planetary protection policy development at national and international levels has not involved significant participation from the private sector. The lack of private-sector participation creates potential challenges for policy development, because private-sector actors need to be able to understand and embrace appropriate planetary protection measures.

Recommendation 6.3: NASA should ensure that its policy-development processes, including new mechanisms (e.g., a revitalized external advisory committee focused on planetary protection), make appropriate efforts to take into account the views of the private sector in the development of planetary protection policy. NASA should support the efforts of COSPAR officials to increase private-sector participation in the COSPAR process on planetary protection.

___________________

15 For example, commercial space groups are widely represented in the Commercial Space Transportation Advisory Committee (COMSTAC), which advises the FAA and other agencies on the development of regulatory standards for safe and competitive space flights. See “Department of Transportation” in Chapter 3. For more information about COMSTAC, see https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ast/advisory_committee.

16 As of August 2017, there were two companies each from the United States. and China and five from Europe that are Associated Supporters. See COSPAR, https://cosparhq.cnes.fr/associated-supporters.

17 The committee has been unable to confirm this with objective data because COSPAR does not collect data on the research or employment background of its associated members, who number in the thousands.

18 Another reason could arise from the lack of interest scientists and engineers have for joint meetings. For example, the history of joint meetings between the International Astronautical Federation (which is rich in commercial engineers) and COSPAR (which is focused on the science of planetary protection) has been disappointing.

19 Two such joint COSPAR-IAF meetings have taken place in recent decades: The first and second World Space Congresses took place in Washington, D.C., and Houston, Texas, in 1992 and 2002, respectively.

20 One such special session, “New Challenger for Planetary Protection,” is being organized at the 2018 IAC in Bremen, Germany.