4

The Health System Landscape

The workshop’s third panel session featured presentations by two speakers who discussed how the health system is addressing some of the challenges facing older adults. Anne Tumlinson, founder of Anne Tumlinson Innovations and founder of Daughterhood.org, addressed navigation of long-term services and supports (LTSS). Lisa Gualtieri, assistant professor of public health and community medicine at the Tufts University School of Medicine, addressed whether technology deployed by a health care system can facilitate or serve as a barrier to care for older adults. Following the two presentations, Deidra Crews, associate professor of medicine and vice chair for diversity and inclusion at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, moderated an open discussion with the panelists.

NAVIGATING LONG-TERM SERVICES AND SUPPORTS1

Anne Tumlinson had spent most of her career thinking that if the nation can create a way to pay for long-term care, it would solve all the problems with caring for older Americans. Then she started having family members and friends who had to interact with the nation’s health and long-term care system and realized that she did not know anything. “One of the most surprising things that I learned in the process of having personal experiences with the system is that just because you have money to pay for

___________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Anne Tumlinson, founder of Anne Tumlinson Innovations and founder of Daughterhood.org, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

something does not mean you are going to get good care, and it does not mean you will be able to find it,” said Tumlinson.

Frailty in old age, a risk everyone faces, is shorthand for the experience of needing LTSS. That need arises, Tumlinson said, from lacking the ability to perform certain types of basic activities of daily living, such as feeding or dressing oneself, without assistance from someone else. According to the Urban Institute, which has developed a model that estimates the risk of needing LTSS over the lifetime, half of all Americans who cross age 65 can expect to need a high level of LTSS at some point in their lives as a result of needing help with two or more activities of daily living or some kind of severe cognitive impairment (Favreault and Dey, 2016). Of those who do need LTSS, about half will need them for 2 or more years, and about 25 percent will need them for 5 or more years. Women, she added, are more likely than men to need LTSS before they die.

Based on an analysis of the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Survey, approximately 10 percent of the population aged 65 and older living in the community—approximately 3.5 million people—has a high need for LTSS (Freedman and Spillman, 2014b). This figure is based on using a narrow definition of LTSS of requiring help with two or more activities of daily living or having severe cognitive impairment and needing help with one activity of daily living or three instrumental activities of daily living, which include activities such as doing laundry, shopping for groceries or personal items, handling bills and banking, making hot meals, or handling medications or injections. Using a broader definition of LTSS need that includes difficulty with two or more activities of daily living, requiring help with one or more activity of daily living, or severe cognitive impairment and needing help with one activity of daily living or three instrumental activities of daily living, the estimate soars to more than 20 percent of the population, or more than 7 million older adults, that requires LTSS.

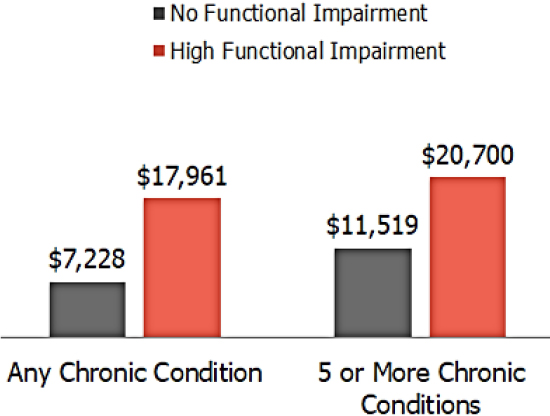

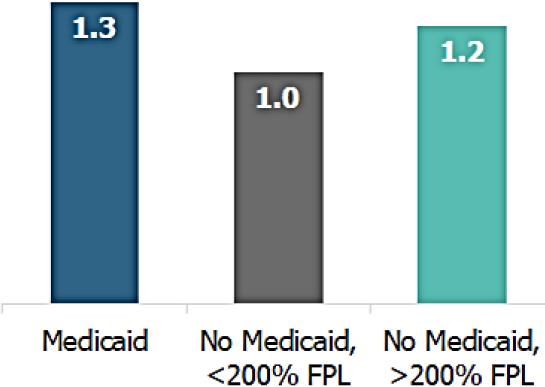

Having a need for LTSS, added Tumlinson, comes with a doubling of one’s health care costs (Windh et al., 2017) (see Figure 4-1). Though Medicaid and long-term care may be synonymous in the minds of many policy makers, only one-third of the 3.5 million older adults who need LTSS are eligible for Medicaid (see Figure 4-2). This is the population, she said, that accounts for an outsized proportion of Medicare spending.

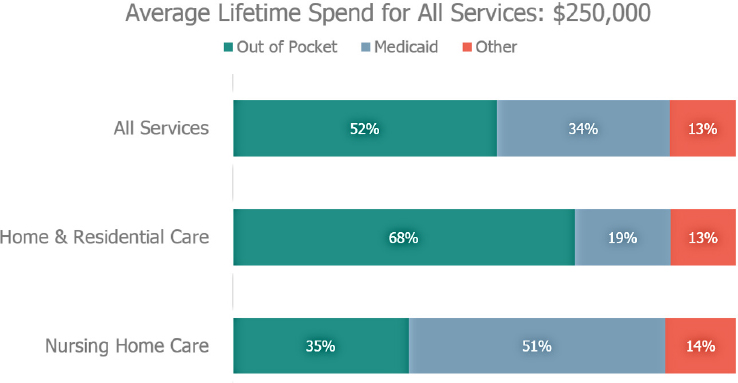

Approximately 75 percent of older adults with a high need for LTSS live at home, with the rest living in a nursing home, assisted living facility, or other facility-based care (Freedman and Spillman, 2014a). Nearly all of those living at home are cared for by family caregivers, and half of them are being cared for exclusively by family caregivers, Tumlinson noted. Eventually, individuals who need help lasting longer than 2 years start using paid care of some kind, and the out-of-pocket costs associated with paid care are substantial (see Figure 4-3). In total, the average lifetime spending for

SOURCES: As presented by Anne Tumlinson at the workshop on Health Literacy and Older Adults on March 13, 2018; Windh et al., 2017.

NOTE: FPL = federal poverty level; LTSS = long-term services and supports.

SOURCES: As presented by Anne Tumlinson at the workshop on Health Literacy and Older Adults on March 13, 2018; Windh et al., 2017.

NOTES: LTSS = long-term services and supports. Percentages may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding.

SOURCES: As presented by Anne Tumlinson at the workshop on Health Literacy and Older Adults on March 13, 2018; Favreault and Dey, 2016.

all paid care services is $250,000 (Favreault and Dey, 2016). Tumlinson noted that the disparity between the out-of-pocket costs for home- and community-based care and nursing home care results from Medicaid policy, which she explained guarantees financing for nursing home care, but not home- and community-based care. The bottom line, said Tumlinson, is that the nation is financing long-term care primarily through the unpaid care provided by family caregivers.

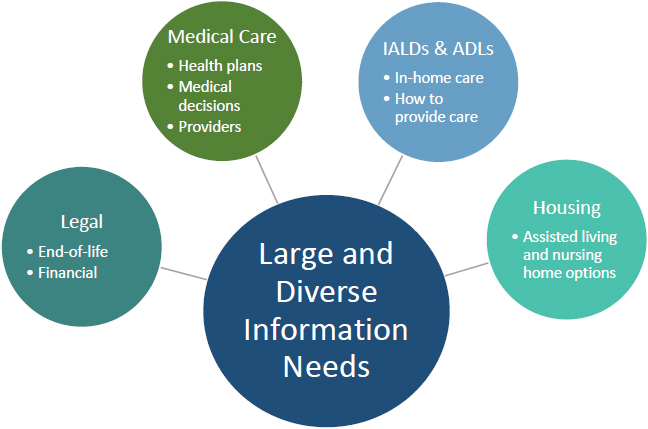

In addition to providing hands-on caregiving that family members are providing—helping with bathing, eating, and dressing—they are also doing a significant amount of management and coordination, as well as making decisions about and handling challenging financial, legal, and family issues (see Figure 4-4). Family caregivers, said Tumlinson, not only have to navigate the medical system for their loved one but they are also navigating the entirely separate LTSS system. The latter requires finding a home care worker or finding an assisted living facility, senior housing, or adult day care center. “I would say they are making [these decisions] in a vacuum,” Tumlinson claimed. “We do not have an infrastructure to support the kinds of decisions that people have to make.” She recalled how a friend and mentor of hers, an expert in long-term care, once said to her that if he had to find home care for his elderly aunt, he would not know where to start

NOTE: ADLs = activities of daily living; IALDs = instrumental activities of daily living; LTSS = long-term services and supports.

SOURCE: Adapted from a presentation by Anne Tumlinson at the workshop on Health Literacy and Older Adults on March 13, 2018.

other than opening the Yellow Book. “I started calling this the Yellow Book problem,” said Tumlinson.

One source of help is area agencies on aging, but there is not enough funding for these organizations to meet the needs for information and support for the growing number of older adults. What is missing, said Tumlinson, are the following three things:

- An ability to match family members with the right types of service supports based on their goals and preferences.

- Resources to support family caregivers in the coordination of all of those services.

- The ability to support family caregivers in the communication that they must engage in among all the disparate parts of the system.

As an example of how hard it is to navigate the long-term care system, Tumlinson talked about Daughterhood.org, the organization she founded and runs. This organization is a community of women across the country, many of whom form local daughterhood circles, that aims to support and build confidence in women who are managing their parents’ care. Recently,

she surveyed the members and asked them what their primary challenge is in finding information. The 100 or so respondents said that information on the Internet is too dispersed or hard to trust; that most “finders,” such as those on Alzheimers.org or eldercare.gov, produce long lists that do not reflect quality; and that many “free” referral sources are biased because they get paid for referrals.

There is also an emotional context to the issues facing family caregivers, who primarily feel overwhelmed, guilty, and alone. “It is hard to consume information when you are panicking and you feel overwhelmed,” said Tumlinson. The other point she made was that health care information that family members receive when their loved one is discharged from the hospital is usually medically focused and excludes long-term care. “It does not say which home care agency or nurse agency to call or how to find an adult day care center so you can go back to work,” she said. “What we need is a care delivery system that revolves around the consumer and family needs and a way for our so-called value-based delivery system to really support this.”

Concluding her presentation, Tumlinson spoke about some innovative, technology-based caregiver solutions that are evolving across three domains: matching, coordination and management, and communication. Matching applications use online directories and in-person support to help individuals find and connect with traditional long-term care providers in their market. Coordination and management applications provide personalized support to address a range of navigational and management issues, such as coordination of health care services, communications with older adults, and applications that use technology to support communications across delivery systems of caregivers and providers. The main challenge for all these applications is formulating a business model that will enable the developers of these applications to make money. “Consumers are not ready to pay out of their own pockets for navigational assistance, despite the fact that they so clearly need it,” said Tumlinson, and selling these applications to employers, providers, and even financial services firms has proven difficult.

TECHNOLOGY AS A FACILITATOR OR BARRIER FOR OLDER ADULTS2

In the last workshop presentation, Lisa Gualtieri discussed RecycleHealth, a nonprofit organization she founded in 2015 to collect fit-

___________________

2 This section is based on the presentation by Lisa Gualtieri, assistant professor of public health and community medicine at the Tufts University School of Medicine, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

ness trackers that people are no longer using and give them to people who might benefit most from their use. To date, RecycleHealth has collected more than 3,000 trackers, including some donated by vendors. She and her colleagues have been using them to conduct research primarily with older adults to learn if they would accept them, use them, and, as a result, increase their physical activity level. Her organization has also worked with community-based organizations to distribute trackers to underserved populations including developmentally disabled adults and veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder.

One new initiative Gualtieri has started works with physicians to understand how data from trackers and other digital health devices can be integrated into clinical care. The goal is to provide them with a display of accurate information about their patient’s activity level since their last appointment and enable them to open discussions about exercise with their patients while being mindful of the limited time physicians have to review the data that trackers produce. From the research she had done with older adults, Gualtieri has found that pivotal points in people’s lives, such as retirement, illness in the family, and death of a spouse, can dramatically change their activity levels (Gualtieri et al., 2016). One key finding from this study was that most people are surprised when they find out how little they exercise in a given day. Other findings were that getting people to make small changes, such as using the stairs instead of the elevator, produces a real increase in activity level that is quantified by the tracker, and that trackers are great for providing a visual reminder of a person’s commitment to increase activity.

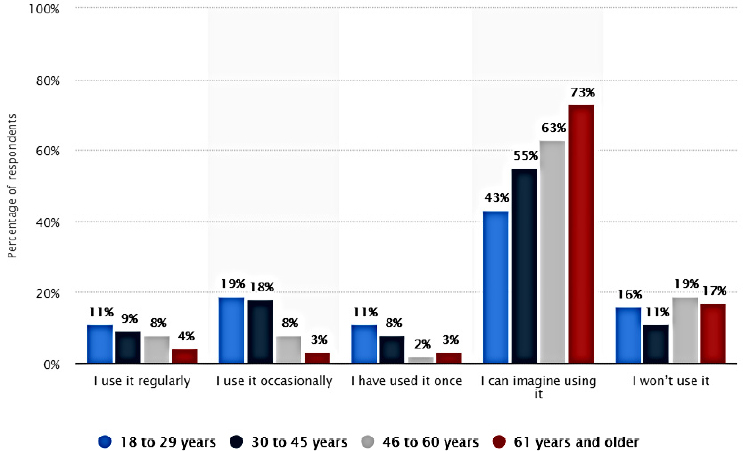

What Gualtieri really wants to uncover are the barriers and facilitators to tracker use, which leads to the larger question of what keeps older adults from accessing digital health. What much of the research she has seen concludes is that older adults are interested in using digital health technologies, but often they are not doing so (see Figure 4-5). When she was recruiting older adults at senior centers in lower-income areas around Boston, she observed that cost and training were two barriers to adoption. “But what we started to discover is that there was a wealth of issues beyond these,” she said. One barrier was that while many older adults own smartphones, they are many generations old or the individuals were on pay-as-you-go plans and could not download apps. Another was that many individuals had never downloaded an app themselves. “We started to see that the barriers to adoption were endless,” said Gualtieri.

Even the design of apps presented challenges to many people. For example, many apps use a spinner to enter in date of birth, and older adults would get frustrated with having to keep spinning to reach their birth year. Gualtieri said some older adults would joke that they had to spin a lot to reach their birth year. Another issue was that the default on some of the

SOURCES: As presented by Lisa Gualtieri at the workshop on Health Literacy and Older Adults on March 13, 2018; www.statista.com/statistics/698633/us-adults-that-would-use-an-app-to-measure-health-metrics-by-age (accessed July 26, 2018).

activity apps was 10,000 steps per day, which she said was far beyond the capabilities of these older adults, as well as many younger adults. “We would provide them guidance based on their current activity level of what might be a good starting point and show them it was easy to change this setting,” said Gualtieri. Her conclusion was that while smartphones are being widely adopted, that does not mean people are adept enough at using them to access the wealth of available digital health tools. “Not being able to access and comfortably use technology becomes a barrier to digital health technologies,” she said.

In Gualtieri’s opinion, a new digital divide is being created, and many older adults are on the wrong side of the divide even if they have a smartphone. Coming to this conclusion has prompted her to try to understand what older adults need to have access to and need to learn to comfortably and adeptly use these new technologies without feeling inept or old simply because the technology is not well designed for this group of older adults or even marketed to older adults.

Gualtieri and her colleagues have been looking at facilitators as well as barriers, and one facilitator is having access to hands-on help that not

only enables older adults to use technology successfully but to feel comfortable using it and not have to depend on having their grandchild set up the device. What she and her interns and students do is go into senior centers and connect with these older adults before trying to teach them about their devices. One of her interns, she recounted, was so calm and patient with these older adults: She was happy to let them tell their life story, and they would enjoy the process of learning how to use their tracker. Now, said Gualtieri, she gets hugs when she goes to these senior centers, and people brag about how many steps they had already taken that day. The challenge, she said, will be to scale this type of high-contact program.

As to how more people can access technology, one step will be to develop apps that work on older versions of smartphones and smartphone operating systems, and another will be to design apps and devices that appeal to and are usable by older adults. For example, Nokia donated some trackers that look like watches but have an extra dial that displays step count. “We discovered that the older adults we were working with liked how it looked, and they liked the comfort of the band, instead of the more typical plastic bracelet-like bands,” said Gualtieri. For many vendors, older adults are not a target population, something that is obvious when reading the directions on how to set up and use most technologies and applications. “As people working in health literacy know, offering simple explanations will increase access for all,” said Gualtieri. One recommendation she offered to vendors is to provide paper, in-person, phone, and online support tailored to the needs and language of older adults. Another was to design their devices and apps to enable information flow and messaging between patient and doctor; that accounts for the complex health needs of older adults and their relationships with clinicians and caregivers.

During her research, one complaint she has heard from older adults is that they have trouble sleeping. Given that, Gualtieri wondered if technology that tracked sleep might benefit many older adults. “That is not something that I have explored as part of my research group, but it is something that I think has enormous potential,” she said. In her final comment, she offered what she considered the most important message for an audience that specializes in health literacy, which was to think carefully about how digital literacy coupled with health literacy can be the road for older adults to access, use, and benefit from digital health.

DISCUSSION

Crews began the discussion by asking Tumlinson to list some of the barriers she sees to further innovation in the space of long-term care support. One barrier, Tumlinson replied, is that the need for information to navigate the health care system is often not connected to the need for infor-

mation to navigate the long-term care system. That information needs to be integrated, she said. A lack of a financing system for long-term care is another barrier, as is information on how to value the various care services that are available. A third issue, she said, is that there is often a great deal of conflict in families and with medical professionals as to what the best course of care is for an individual.

Crews then asked Gualtieri for her ideas as to what would make the older adult market attractive to manufacturers and developers. Gualtieri replied that this issue comes down to one of perspective in terms of whether it is more important to make as much money as possible or to help more people achieve their health goals and still profit. She added that even with the growing population of older adults, too many manufacturers do not see older adults as a high-profit market and that it would be advantageous to their business model to design their products to appeal to older adults.

Christopher Trudeau from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences asked Tumlinson to talk about the general legal needs that she has seen most often through her interactions with Daughterhood. “The greatest challenge that I hear about is confusion over roles among siblings,” said Tumlinson, which she said leads to issues about money and control. Another area of conflict she has seen is when one sibling is providing all the care for a parent and wants to be paid and another sibling disagrees. What is needed for those situations, she said, is a legal and social framework to help the family function as a caring system for their older parent.

Trudeau also asked if Tumlinson had any ideas on how to design a long-term care delivery system that integrates the legal, social, and medical sides. Tumlinson said she did not have an answer to that question, but whatever the answer is will depend on long-term care providers or medical providers recognizing and identifying the legal and social needs as they arise in the context of their practices.

Thomas posed the question of why there is no equivalent to Angie’s List for long-term care. Tumlinson said Thomas is one of many people, including herself, who have asked that same question. In fact, she added, there is something similar, called caring.com, but people do not want to subscribe to it as they do to Angie’s List. Tumlinson explained that, as a result, caring.com is supported by the facilities that advertise with the site, which gives them higher placement in the generated lists. She added that another issue is that people do not want to review sites because they worry about the ramifications for their family members. Part of what Tumlinson is trying to do with daughterhood circles is create friend groups from existing communities so that people can get word-of-mouth referrals, just as they do when they need a plumber.

Jay Duhig from AbbVie Inc. applauded Gualtieri’s pointing out that adoption is more than just “if you build it, they will come.” He asked her

if any of her research has looked at the effectiveness of providing a device in concert with a drug or other therapy as part of a treatment regimen. Doing so might address a patient need and create a market for such a device. In fact, said Gualtieri, she has a friend who is a psychiatrist who gives some of the trackers she collects to patients when he gives them new medications as a means of looking for side effects, such as becoming increasingly sedentary or having sleep problems. She also provided a tracker to someone who was in a rehabilitation center and had that person use it to track the progress the individual was making in physical therapy. Establishing a tracker lending library might be one way of encouraging physicians to prescribe a tracker along with a new medication. “That might be my next research project,” she said.

Lawrence Smith from Northwell Health asked if it makes a difference in terms of success at home whether the older adult has sons or daughters and how far the child lives from home. Tumlinson said that she does not know of any research that asked those specific questions, but she does have research on what a difference it makes when the family member has support. One study she did with an organization that provides nurse practitioner support to the family caregiver looked at integrating the family caregiver into the medical team and providing the caregiver with some monetary support as a means of reducing emergency department and ambulance use. The results showed a reduction in hospital use. “More support for the family helps it do a better job and creates better outcomes,” said Tumlinson.

Koss noted that the Consumer’s Checkbook in Washington, DC, and San Francisco both list local resources with provider ratings, as well as an Angie’s List–type service for several health care services. She then noted that elder abuse occurs most often at the hands of a family member, and the more isolated an individual is, the easier it is to abuse the person emotionally, financially, and physically. She also said she is a firm believer in the individuals stating their preferences, but the tensions among family members around the preferences and how they get resolved often falls to the legal system. Given that, she asked the panelists how to take those facts into account when thinking about how to involve families in the care of their older adults.

Tumlinson responded that she has no ideas for avoiding the legal system in those types of situations, though she suspects that better educating everyone about all the issues involved in caring for their older family members would help. “It is just so important for individuals to set up their wishes, make them clearly known, and really think through the ramifications in advance of being in a dire situation,” she said. When people ask her how to prevent themselves from being a burden to their children, her advice is to tell them what they want now and give them permission now to take

steps such as taking away their keys when the time is right in the future or what to do if one sibling becomes difficult. “These are conversations that the sooner you can have them with each other in as honest a setting as possible, the less you are going to be running into situations where you have lost control of a loved one’s care,” said Tumlinson.

Regarding elder abuse, Super noted there are technology solutions that can address financial exploitation and there are arrangements that can be made with banks to prevent a sibling from making unusual withdrawals or transfers of funds. The broader issue is that most instances of elder abuse arise from an economic need, lack of education, or other societal need that must be addressed. As an example, she cited a case in which adult protective services stepped in to take charge of an elderly woman who had horrible bed sores and found that her illiterate adult son had never been told that he had to turn his mother to prevent bed sores. “I do not think that he meant to abuse his mother,” said Super. “He simply did not have the skills he needed to care for her.”

Lindsey Robinson from the American Dental Association noted that many medications older Americans take can have a significant effect on oral health. She wondered if families and caregivers are aware of the relationship between oral health and medications and if they have a hard time finding dental care for their loved ones, particularly given that Medicare does not include a dental benefit. Tumlinson replied that this a big issue, and there is little understanding among the public about the ramifications of medications. She has also heard of a great deal of stress among caregivers around dental care for their parents.

Super commented that n4a has a new national resource center for engaging older adults. The grant for this program requires a focus on creativity and arts, technology, generational issues, and lifelong learning. She also noted that there is a program in New York City, Older Adults Technology Services, that provides older adults with hands-on training to use their own devices, as well as on how to use technology-enabled exercise equipment. She then asked Gualtieri if she has looked at hands-on training that benefits older adults with technology. Gualtieri replied that many programs similar to the one in New York are focusing on clients at senior centers to increase the digital literacy of older adults. The problem, she said, is that devices such as iPhones are marketed as being easy to use, which leaves people thinking they should be able to learn how to use them on their own. Too often, when they cannot, they enlist someone to set the device up for them, which does not provide the opportunity to learn more about the device. This is why she believes in the importance of hands-on training. When RecycleHealth gives a tracker to someone, she or one of her colleagues sits with them and walks them through the set-up process and helps them configure the device to meet their needs and change the settings

as they progress. Classes are fine, but hands-on instruction is what is really needed when working with older adults, she said.

Zimmerman commented that Silver Spring Village offers an informal program on technology just for people with Android devices. It is offered every 2 weeks at the local recreation center, and it involves village members helping other village members, which Zimmerman said makes the program work. She also noted a problem she has with trackers, which is that she does not have touch sensation in her fingers anymore, which makes it impossible to pull little buttons out from the side of the device to configure it. Gualtieri agreed that form factors are important for older adults and that dexterity can be an issue with many devices. She also noted that some devices send too many messages that do nothing to help motivate and support people in reaching their fitness goals.

Nicole Holland from the Tufts University School of Dental Medicine asked if trust issues related to big data and tracking health information are a barrier for older adults to use technology. Gualtieri replied that she asked people in her initial studies if they were concerned about the privacy of their information. “We got the exact same from almost everybody, which is given credit card breaches, given whatever the latest massive breach in the news was, if somebody has access to my height, weight, and how many steps I walked today, I do not really care,” said Gualtieri. People are so numb to some of the privacy issues that she worries that the trust level is greater than it should be.

Alicia Fernandez from the University of California, San Francisco, remarked that she takes care of very low-income individuals, usually immigrants, and for a while she tried misguidedly to get her patients to use their automatically loaded fitness app on their smartphones to keep track of their steps. She also recounted how 6 or so years ago she tried to buy her mother, who was having issues with cognitive impairment, a simple phone and would have been willing to pay twice what she paid for her smartphone. None existed then, which she says is a market failure. She noted that who pays for care is a critical issue. In San Francisco, for example, ride-sharing services are starting to bill Medicaid for ride shares to medical appointments, and that a service called GoGoGrandparent allows an older adult to call someone who will then order a ride share using preloaded information. “Perhaps that is the way to go rather than trying to train every individual to be able to do these things,” said Fernandez. She wondered, too, if it might be more useful to provide a walking partner who wears the tracker instead of training an older adult to use one.

Gualtieri agreed that there is a significant market failure when it comes to products for older adults. There have been smartphones designed to be simple, but she wonders if they were tested with the intended population and designed with a real understanding of what functions an older adult

wants in a simpler phone. Regarding who pays for these technological solutions, Gualtieri said the challenge is to develop a cost–benefit argument. “If you can give someone a tracker and it is going to increase people’s health, decrease hospitalizations, et cetera, then it is a worthwhile expenditure for an insurance company,” she said.

Gualtieri has studied the failure of corporate wellness programs and believes there is a lesson that can be applied to the use of technology with older adults. The programs that failed, she said, were offering a service that many employees did not care about or want. Similarly, handing a tracker or providing a smartphone app to someone who does not want it or care about it is not going to lead to success. The problem, she said, is that programs pay for these services or technologies without thinking about how to integrate them into people’s lives and what kind of training is needed to help them use services or technologies in a way that fits into their lives.

Addressing the idea of walking partners, Gualtieri said the social support aspect of having a walking buddy is powerful, but the challenge is orchestrating how walking groups form. “You need people who like each other and have something to talk about because that is motivating, and it makes it fun instead of just exercise,” said Gualtieri. “You need people who have similar schedules and who walk at similar paces for something like this to work well.” One thing she suggested to members of one of the senior centers where she worked was to organize car pools for walking sessions at the mall when the weather was bad.