4

Sustainability and Healthy Dietary Changes Through Policy and Program Action

In Session 3, moderated by David Klurfeld, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Beltsville, Maryland, speakers continued to explore program and policy actions that could support sustainable diets, based not just on modeling but on a variety of other types of studies as well. This chapter summarizes the presentations and discussion that took place, with highlights of the presentations provided in Box 4-1.

THE HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL ASPECTS OF DIETARY CHANGES TOWARD SUSTAINABLE DIETS

Citing the same Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) definition of sustainable diets referenced by other speakers (FAO, 2012b; see Box 2-2 in Chapter 2), Marco Springmann, Oxford University, United Kingdom, began by remarking that he would be addressing only two of the several dimensions of sustainable diets: human health and the environment.

Regarding the health impacts of food consumption, Springmann highlighted that, according to 2015 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) data, imbalanced diets are responsible for the greatest health burden globally and in most regions as well. (See Chapter 3 for a discussion of how GBD analyzes human dietary data.) Food insecurity remains a pertinent problem as well, he observed, with 2 billion people worldwide being overweight or obese, another 2 billion having nutritional deficiencies, and 800 million experiencing hunger due to poverty and poorly developed food systems (FAO et al., 2018). He stressed that the situation is expected to become worse if nothing

is done to reverse the dietary transition currently under way (Alexandratos and Bruinsma, 2012; Springmann et al., 2016b). Regarding the environmental dimension of sustainable diets, Springmann noted that food production is a major driver of climate change (Vermeulen et al., 2012); land use change and loss of biodiversity (Houghton et al., 2012; Ramankutty et al., 2008); freshwater extraction (WWAP, 2012); and fertilizer runoff and dead zones (Diaz and Rosenberg, 2008; Vitousek et al., 1997).

In light of these findings, and given the number of systematic reviews of this evidence that are beginning to appear (Aleksandrowicz et al., 2016; Hallström et al., 2015; Joyce et al., 2012; Nelson et al., 2016), Springmann believes the sustainable diet literature has reached what he described as a

“first point of maturity.” However, he observed, much of the work still revolves around national case studies, which feature widely varying reference diets, environmental footprints, and scenario designs. He emphasized that this variation complicates comparisons across studies and makes it difficult to make sense of the totality of the literature. In addition, he noted, the predominant focus with respect to environmental impact has been on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and only a few studies have examined land and water use. Moreover, he said, health impacts often are not explicitly analyzed beyond adherence to national dietary guidelines or directional changes in nutrient levels (Payne et al., 2016).

A Combined Analysis of the Health and Environmental Impacts of Sustainable-Diet Strategies

Springmann went on to discuss a combined analysis of the health and environmental impacts of sustainable-diet strategies across 158 countries.

Methods: The Dietary Change Strategies Analyzed

Springmann explained that the analysis covered three different dietary change strategies and their predicted impacts by 2030.

The first strategy (“environmental objectives”) was based on what many studies have revealed about the environmental impacts of animal-source foods. In a series of four scenarios, Springmann reported, the model reduced animal-based products and substituted plant-based products (two-thirds legumes and one-third fruits and vegetables) based on observational data on dietary patterns (how vegetarians change their diets compared with omnivores). The scenarios ranged from 25 percent substitution for animal-based foods to 100 percent substitution.

The second strategy (“food security objectives”) addressed energy imbalances, including both underweight and overweight and obesity. Again, a series of scenarios was modeled, ranging from 25 to 100 percent reduction of energy imbalance.

The third strategy (“public health objectives”) adopted nutritionally balanced dietary patterns developed by the EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems and regionalized based on country-level preferences for types of grains, fruits, and meats. Springmann explained that because these dietary patterns were also energy-balanced patterns, this third strategy addressed the same energy imbalances addressed by the second strategy. Again, a range of scenarios was modeled: flexitarian, pescetarian, vegetarian, and vegan dietary patterns. Springmann pointed out that all of these patterns are predominantly plant based—even the flexitarian dietary pattern, which includes meat-based products but in amounts that are much smaller than those in an omnivore diet. For example, the flexitarian pattern that was modeled included only 100 grams of red meat per week.

Methods: The Modeling Framework

Springmann and his research team used a coupled modeling framework supporting five analyses: (1) a mortality analysis that involved a comparative risk assessment with nine dietary and weight-related risk factors and five disease endpoints based on the Oxford Global Health model (Springmann et al., 2016a,b); (2) an environmental analysis of country-specific footprints

for GHG emissions, cropland use, freshwater use, nitrogen application, and phosphorous application (Springmann et al., 2018); (3) a regional analysis that entailed grouping all 158 countries by income (Robinson et al., 2015); (4) a nutritional analysis of 24 nutrients, based on the GENuS dataset (Smith et al., 2016) and USDA data (for vitamins B5 and B12), relative to World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations; and (5) an economic analysis of food expenditures based on country-specific estimates of food prices (Robinson et al., 2015).

Springmann observed that the Oxford Global Health model used to conduct the mortality analysis is similar to the modeling work of GBD. In addition, he noted that the environmental analysis was not life cycle based. He explained that there are two different ways of accounting for environmental impacts, one being to track at a very detailed level every emission from producing a food (i.e., life-cycle analysis [LCA]). Without going into detail, he mentioned only that the other method, which he and his team used, is a more mechanistic approach that he believes is arguably more comparable across regions and countries. (See Chapter 5 for additional discussion of the role of LCA in understanding the environmental impacts of a food system.)

Results: Mortality Analysis

According to Springmann, the mortality analysis revealed about a 10 percent reduction in premature mortality in 2030 with both the environmental strategy (the first strategy described above) and the food security strategy (the second strategy described above). The reduction associated with the environmental strategy was slightly larger, he noted, mainly as a result of increased vegetable consumption when animal-based products were replaced by plant-based products. With the food security strategy, most of the reduction in premature mortality resulted from reductions in obesity, followed by reductions in underweight.

Springmann went on to report that, because the public health strategy essentially doubles the health benefits of the food security strategy by balancing the nutritional composition of not only diet but also energy, the reduction in premature mortality associated with that strategy was similarly approximately double that of the food security strategy. It was also approximately double that of the environmental strategy. Rather than delving into any detail as to how the four public health strategy dietary scenarios (flexitarian, pescetarian, vegetarian, and vegan) compared with each other, Springmann wanted only to emphasize that all four scenarios were better in terms of reduced premature mortality than any of the other strategies (i.e., environmental or food security).

Results: Environmental Analysis

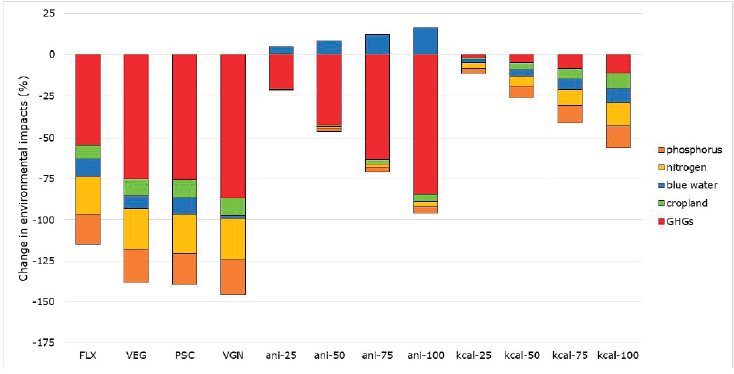

As with premature mortality, Springmann continued, all three strategies yielded reductions in environmental impact (see Figure 4-1). He explained that with the food security strategy, because there is a greater percentage of overweight and obese people than underweight people worldwide, correcting for energy imbalance effectively removes food from the system, and consequently the environmental impacts of that food.

With the environmental strategy, whereby animal-based products are replaced with plant-based products, “the story is a bit different,” Springmann said. The removal of animal-based foods led to a very high reduction in GHG emissions, thus accounting for the overall reduced environmental impact of all four scenarios. However, because many plant-based foods use a

NOTES: ani-25 = 25 percent replacement of animal-based foods with plant-based foods; ani-50 = 50 percent replacement of animal-based foods with plant-based foods; ani-75 = 75 percent replacement of animal-based foods with plant-based foods; ani-100 = 100 percent replacement of animal-based foods with plant-based foods; blue water = freshwater; FLX = flexitarian diet; kcal-25 = 25 percent reduction in overweight, obesity, and underweight; kcal-50 = 50 percent reduction in overweight, obesity, and underweight; kcal-75 = 75 percent reduction in overweight, obesity, and underweight; kcal-100 = 100 percent reduction in overweight, obesity, and underweight; PSC = pescetarian diet; VEG = vegetarian diet; VGN = vegan diet. Environmental impacts include greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, cropland use, freshwater use, nitrogen application, and phosphorous application.

SOURCE: Presented by Marco Springmann on August 1, 2018.

great deal of water, as shown in Figure 4-1, the environmental impact with respect to water use actually increased across all four dietary scenarios.

Again, Springmann reported, with the public health strategy, combining reductions in energy imbalance with a more balanced formulation of dietary intake by food group resulted in reductions in overall environmental impact much larger than those for either of the other strategies. However, some of the specific impacts, such as for water use, were not large.

Results: Regional Analysis

Springmann noted that the above results paint a global picture. He explained how grouping all 158 countries by income (high income, upper middle income, lower middle income, and low income) reveals regional specificity.

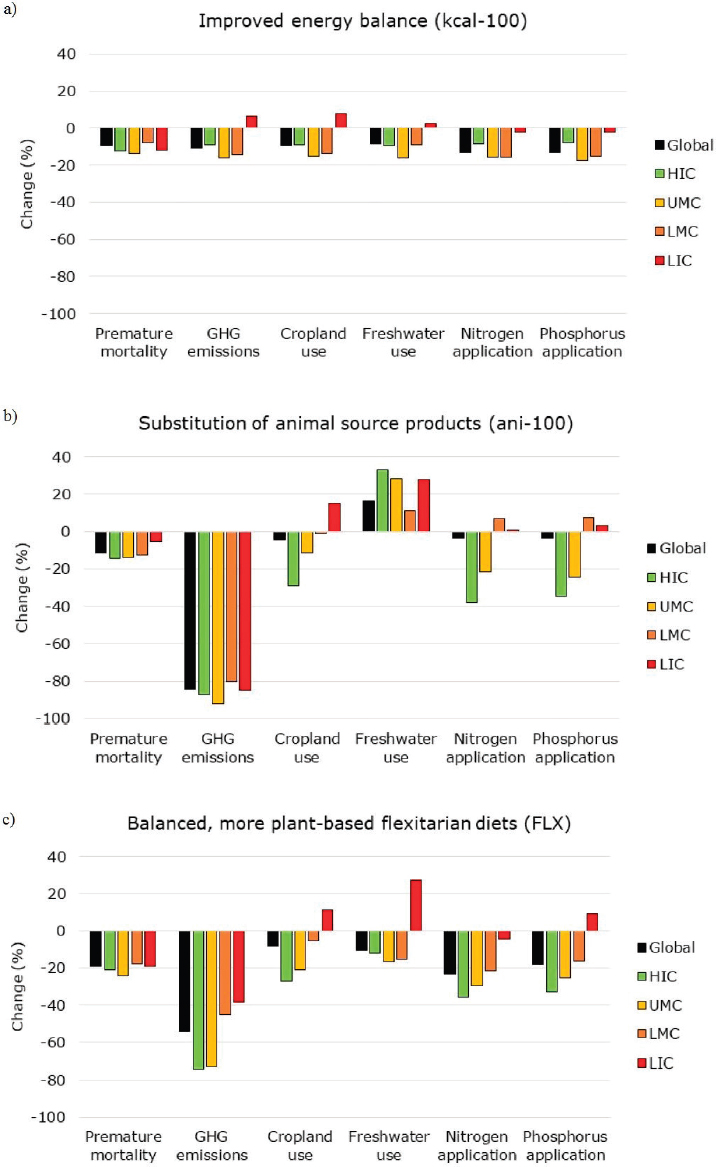

With the food security strategy, Springmann reported, all regions except low-income countries would be expected to experience small reductions in all of the measured health and environmental outcomes by 2030 (see Figure 4-2a). He interpreted these findings to mean that people in low-income countries consume too little, and that addressing energy imbalances would actually increase consumption and along with it, cropland use, GHG emissions, and freshwater use. Nitrogen and phosphorous applications, however, would be expected to decrease slightly because of future technological improvements anticipated to outweigh any increases that would otherwise occur.

In contrast, Springmann continued, with the environmental strategy scenarios, large reductions in GHG emissions occurred across all regions (see Figure 4-2b). In addition, he observed, all regions would be expected to undergo reductions in premature mortality, although those reductions would not be expected to be as large in low-income countries because these countries do not consume as many animal-based products that could be substituted for. Low-income countries would also experience a very high increase in cropland use, while all of the other regions would experience reductions. Freshwater use would increase everywhere, and the application of both nitrogen and phosphorous would increase in both low- and middle-income countries.

With a public health approach, Springmann noted, the impacts would be a little more balanced. Still, he said, “you do not get reductions everywhere. There are trade-offs.” For example, with the flexitarian diet (see Figure 4-2c), all regions would see reductions in premature mortality, GHG emissions, and nitrogen application. While most regions would also see reductions in the other impacts, cropland use, freshwater use, and phosphorous application would all increase in low-income countries.

Results: Correlation Analysis

Another way to look at these same data, Springmann continued, is to draw regional correlations between the health and environmental impacts among the different diet scenarios. Doing so reveals aligned impacts (i.e., correlations are positive) in middle- and high-income countries under most of the diet scenarios. In contrast, in low-income countries, most of the correlations are negative. Springmann explained that technologies are a major factor when one is projecting food production, particularly in low-income countries. But even with projected technologies and intensified production, he said, “there is basically no way you can align [the impacts] by 2030,” although by 2050, there should be greater alignment (i.e., fewer negative correlations between health and environmental impacts in low-income countries).

Results: Nutritional Analysis

Usually when people talk about the nutritional impacts of dietary change, Springmann observed, they focus on proteins. In this analysis, proteins were not a problem nutrient for the most part, with only low-income countries projected to have any deficiencies by 2030 and only by 1 to 2 percent in a couple of the diet scenarios. But in most other countries and under most other scenarios, protein should not be a problem. Without going into detail, Springmann commented that other nutrients, such as the B vitamins and calcium, would need to be supplemented in some regions under some of the scenarios.

Results: Food Expenditure Analysis

Springmann commented briefly on the food expenditure results. With the environmental strategy, weekly food expenditures would increase because fruits and vegetables are usually fairly expensive. In contrast, weekly

NOTE: GHG = greenhouse gas; HIC = high-income country; kcal = kilocalories; LIC = low-income country; LMC = lower-middle-income country; UMC = upper-middle-income country.

SOURCE: Presented by Marco Springmann on August 1, 2018.

food expenditures would decrease under the food security strategy—at least globally—because people would be eating less food. With the public health strategy, people would be eating better, but also less, in all the scenarios except pescetarian; therefore, the increased price associated with greater fruit and vegetable consumption would be compensated by the reduced price associated with eating less food. Thus, again at the global level, weekly food expenditures would decrease for all the scenarios except pescetarian, because fish are very expensive. Springmann added that when countries are categorized by region, the predictions for the public health strategy differ considerably, with low-income countries experiencing large increases in weekly food expenditures under all four public health scenarios. “That is a big problem,” he said.

Final Remarks

In summary, Springmann stated that improving nutrient levels and reducing diet-related premature mortality is possible in all regions of the world, but that only in high- and middle-income countries would that achievement be aligned with a reduction in environmental impacts. He called for a synergistic perspective on sustainable diets that takes account of regional considerations, including technological changes and perhaps international support mechanisms. He noted that while reducing GHG emissions is important at the global level for mitigating climate change, other environmental impacts are more context-dependent.

Among the three different dietary change strategies tested, Springmann advocates the public health strategy. A strategy that balances dietary intake and food composition could, he said, “deliver quite a bit and a way to achieve sustainable diets.” However, he cautioned that currently, most national dietary guidelines do not actually reflect the evidence on healthy eating used to deduce the dietary patterns modeled in his team’s analyses, incorporating no or overly lax limits for animal-source foods, particularly dairy. In this regard, he considers the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) to be especially problematic and they are unsupported by the evidence base. “Updating national dietary guidelines should be a priority,” he concluded, if such guidelines are to reflect the latest evidence on eating for both health and environmental sustainability.

REDUCING THE CARBON FOOTPRINT WITHOUT SACRIFICING AFFORDABILITY, NUTRIENT DENSITY, AND TASTE

For Jennie Macdiarmid, University of Aberdeen, Scotland, the key challenge for sustainable diets is to combine nutritional security with measures to address climate change. Given the substantial contribution of livestock

to climate change, she and her research team have demonstrated, through modeling, that it is possible to have a diet that meets all nutrient requirements, is affordable, and has as low a carbon footprint as possible (90 percent reduced). “Within reason,” she said, “you can optimize just about anything.” But to get that 90 percent reduction in GHG emissions, she elaborated, would require eating nothing but bran flakes, pasta, peas, a few onions, and a bit of chocolate (Macdiarmid et al., 2012). “Remember,” she said, “you are putting water on your bran flakes.” She emphasized that one cannot rely on modeling alone to develop sustainable diets; rather, “we have to have that human input.”

For a slightly more realistic diet, Macdiarmid and her research team added what they called an “acceptable” element into the same model, entailing a diet that would be more familiar to people. Again, the researchers were able to identify a combination of foods that was nutritionally adequate; with a low carbon footprint; affordable; and, in this case, also tasty. This diet contained many more food items, including small amounts of meat and dairy. The trade-off, however, was lowering the reduction in GHG emissions from 90 percent to only 25 percent.

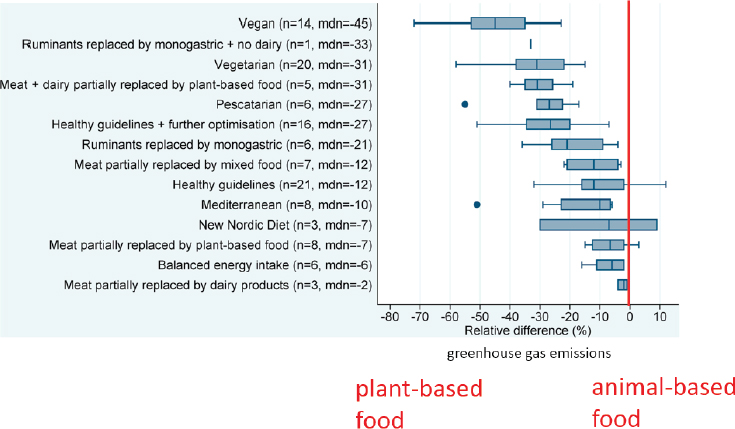

Like Springmann, Macdiarmid commented on the number of systematic reviews conducted since this first modeling work was done, highlighting one review in particular. Aleksandrowicz and colleagues (2016) concluded that not only do plant-based diets result in lower GHG emissions relative to animal-based diets, but, more interesting in Macdiarmid’s opinion, there is a range of plant-based diets with lower GHG emissions than animal-based diets (see Figure 4-3). “We mustn’t think of a vegan diet,” she stressed. “There is a whole range of vegan diets that can have implications for environmental impact.” She added that vegan diets are probably not what they used to be. “It used to be lentils,” she said, but now, such ingredients as coconut milk are being used. She emphasized the need to think about taste, not just putting foods together.

Reducing Meat Consumption: Questions and Concerns

Macdiarmid observed that discussions on reducing consumption of animal-source foods tend to focus entirely on meat. This focus, she stated, has fueled a great deal of research, a great deal of panic, and a great deal of media attention around protein and a fear that reducing meat consumption would lead to protein deficiency. She questioned whether this is a valid concern. She explained that in a recent study on nutrition security in the United Kingdom, she and her colleagues found that, between imports and domestic production, the UK protein supply is almost twice the population-level recommended intake (grams per capita per day) (Macdiarmid et al., 2018). Even if all meat were removed from the supply chain, she noted, the country

SOURCES: Presented by Jennie Macdiarmid on August 1, 2018, modified from Aleksandrowicz et al., 2016.

would still have about 125 percent of its recommended protein supply. In her opinion, the attention focused on protein replacement is a distraction from other problem nutrients. She added that in all of the modeling that she and her colleagues have done, regardless of the combinations of foods they have tested (i.e., healthy and with low GHG emissions, healthy and with high GHG emissions, unhealthy and with low GHG emissions, and unhealthy and with high GHG emissions), the one outcome they have always derived is achieving the necessary amount of protein (Macdiarmid, 2013).

Macdiarmid then turned to the other issue around meat consumption—acceptability. “If we want people to change their diets,” she asked, “how are we going to frame this?” This question is absolutely key, in her opinion, given that reducing meat consumption is currently not an acceptable notion, certainly not among most of the population and some governments. She cited another recent study in which her research team asked people whether they would be willing to reduce their meat consumption. Most people said no, although some said yes, and some said they would think about cutting down (Macdiarmid et al., 2016). Among those who said they would not eat less meat, reasons provided included “I like meat,” “It fills me up,” “I am not doing it if others will not,” “It is important to me,” and “Actually, it will make no difference whatsoever [to climate change].” It is because of responses like these, Macdiarmid said, that it is so important

for the alternative diets being offered to be ones that people can “engage with” and are willing to eat.

Macdiarmid then alluded to the large body of research on replacing meat with legumes and various other plant-based foods. She noted as well the current trend around consumption of insects. Even in Scotland, she observed, there is a hotel that has announced it will be serving midge burgers. For her, not only does that sound unpleasant but also, and more important, insects are bioaccumulators and therefore can accumulate such contaminants as heavy metals. Thus, she highlighted the lack of debate around food safety issues associated with insects. “We need to look at the whole picture,” she cautioned, “and not just say, ‘This would be a good protein replacement.’” In her opinion, moreover, the insect trend is distracting from what really needs to be examined with respect to changing diets. As an example, she pointed to the low intakes of fiber in many developed countries. She suggested that this nutrient deficiency could be a more important concern than protein intake in framing the need to reduce meat and switch to a plant-based diet that would be beneficial to both health and mitigation of climate change. She added that another food being investigated is lab meat, and said she recalled a recent claim that a company had created a vegan burger that tastes exactly like meat.

Regarding the argument that reducing meat consumption could result in less costly diets, Macdiarmid remarked that whether this is true depends on what food is used to replace the meat, as well as what the resulting overall diet looks like. “We have to remember that we do not eat individual foods,” she said. “We eat a collection of foods in meals and our total diet.”

The Importance of Taste, Choice, and “Preswallowing” Nutrition

Although Macdiarmid agreed with others that data on sustainable diets could be refined and made more accurate (an issue that arose in the discussion at the end of the previous session, as summarized in Chapter 3), she also agreed that there are enough data and enough understanding of diets and food systems now both to improve nutrition and health and to mitigate climate change (again see Chapter 3, but also the summary of Fanzo’s presentation in Chapter 2). She added that quite a bit is known about the implications of the food system for natural resources as well. But, she said, “The thing that we keep forgetting in all this discussion is around food choices. Most people do not eat just for health reasons. Most people do not eat just because they want to protect the environment.” She called for a more integrated understanding of some of the factors that are actually driving what people are eating.

Macdiarmid pointed out that national dietary guidelines have existed for a long time and are often held up as evidence of accomplishments in

public health nutrition. Yet, she stressed, “people still are not eating healthy diets.” With respect to issuing recommendations for sustainable diets, she questioned how such recommendations would actually be implemented. She cautioned that, like national dietary guidelines, such recommendations would “get stuck” at the guideline stage absent more thought about what drives people to eat what they eat. For her, the reality that people eat for different reasons raises another key point: that everybody is different. There is no average person and there is no average diet.

Borrowing from Crotty (1993), Macdiarmid referred to the habits, desires and preferences, social influences, affordability, and other factors that drive people to make food choices—in other words, what happens before they eat—as “preswallowing nutrition.” In contrast, “postswallowing” nutrition encompasses what happens biologically, or physiologically, after food is swallowed. “We focus so much on the postswallowing nutrition” and what foods do in terms of health, Macdiarmid observed, that “we have forgotten a little bit about preswallowing nutrition.” Yet, she argued, preswallowing nutrition is extremely important when thinking about how to encourage people to change what they are eating.

Macdiarmid emphasized further that the context of eating varies across countries and across cultures within countries. To illustrate this point, she shared a response from a focus group study on willingness to reduce meat consumption: “I’m aware of the environment. I take other steps, I do my bit, recycling, driving less, but I probably wouldn’t change diet” (Macdiarmid, 2013).

In addition to culture, Macdiarmid continued, social networks also matter. People tend to act the way people in their social networks act. In a study in which participants were asked whether they would be willing to reduce their meat consumption, one response was, “I don’t want people to think I’m strange or a hippy” (Lea and Worsley, 2003).

Finally, Macdiarmid emphasized, identity influences food choice as well. “Food tells an awful lot about us,” she observed. She cited a study with children who were asked to describe different foods. Boys described meat as “outgoing, popular, physically impressive, and attractive to girls,” whereas girls described it as “a fat, smelly man sitting in the corner of a bar” (Elliot, 2014). She mentioned the nongovernmental organization (NGO) in the United Kingdom called Part-Time Carnivores, which found that that name attracted more men than if it were to refer to itself as being for “flexitarians” or “vegetarians.” She interpreted this finding to mean that calling themselves “carnivores” gives men an identity that “flexitarian” or “vegetarian” does not. “These sorts of social things are really important to think about,” she stressed.

Also important, Macdiarmid continued, is thinking about how people behave in different settings. She cited a study done a number of years ago

replicating some of the work of John de Castro,1 which showed that the amount of food people eat varies depending on the people, the number of people with whom they are eating, and where they are eating.2 When eating with family or friends, people tend to eat more than when eating with work colleagues, she reported, and when eating in a restaurant, people tend to eat more calories than when eating at home.

Final Remarks

In summary, Macdiarmid reiterated that it is possible to model an ideal diet. She cautioned, however, that “leaving a computer to come up with it” will not necessarily lead to the change needed to achieve a sustainable diet. Rather, she argued, one should consider eating habits and behavior. She underscored the need to think about what can be done to get people to change their diets. In addition, she highlighted the need to remember that there is no such thing as an average diet. Without providing details, she briefly mentioned work of her research team showing that there are many different ways in which people can change their diet to achieve nutrient requirements while also reducing GHG emissions, and that the optimal way varies among individuals.

Finally, Macdiarmid highlighted the need to think of the food system not as a linear process but as one with many feedback loops. She emphasized that consumption is a product not just of processing and distribution but also of acceptability, preferences, the nutrition transition, cultural and social factors, and economic access.

A MENU OF SOLUTIONS FOR A SUSTAINABLE FOOD FUTURE

Building on Macdiarmid’s call to better understand what drives people to make dietary choices, Janet Ranganathan, World Resources Institute (WRI), Washington, DC, discussed lessons learned from the private sector about how to shift behavior. First, however, drawing on the WRI report Creating a Sustainable Food Future,3 she posed the question of how the world can feed nearly 10 billion people in 2050 in a manner that advances development and well-being while reducing pressure on the environment. “This is the question,” she asserted, not just for this workshop, but for

___________________

1 For more information, see de Castro (2000).

2 Personal communication, S. Whybrow, European Congress of Obesity Conference, 2009.

3 Final version forthcoming. Published installments can be viewed on the WRI website: https://www.wri.org/our-work/project/world-resources-report/world-resources-report-creatingsustainable-food-future (accessed December 18, 2018).

humanity. She has worked on almost every environmental issue during her 23 years at WRI, and every issue—from deforestation, to climate change, to eutrophication, to biodiversity—always comes back to food. Food, she said, is “the mother of all sustainability issues.”

Ranganathan explained how addressing this question requires balancing three needs. First, the world needs to close the 56 percent calorie gap between 2010 and 2050, that is, the 56 percent increase in calories that WRI has predicted will be needed to feed 9.8 billion people by the latter year. According to Ranganathan, WRI predicted this gap even while assuming an additional 540 billion hectares of agricultural land and large yield improvements on par with what occurred with the green revolution. (WRI’s calorie gap analysis was based on Alexandratos and Bruinsma [2012]; Bruinsma [2009]; FAO [2017a]; and UNDESA [2017].)

Second, Ranganathan observed, given that 28 percent of the world’s people are employed in agriculture but that agriculture represents only about 3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) globally (according to World Bank data) and about 1 percent in the United States, the incomes of farm workers are low. Yet, she stressed, the world needs agriculture to support economic development. She mentioned just having attended a Farmer Income Lab addressing the problem that farmers in the food company supply chains that end in developing countries are not making a living wage, adding that this explains in part why many of these people are moving to cities. She asserted that this low-income problem needs to be addressed as well while closing the calorie gap.

Third, Ranganathan identified the need for the world to reduce agriculture’s impact on the environment. Currently, she observed, WRI analysis indicates that about one-quarter of the world’s GHG emissions are due to agriculture when land use change is taken into account. In addition, 37 percent of the Earth’s landmass (excluding Antarctica) is devoted to food production. Ranganathan pointed out that, just within her own lifetime, the agricultural footprint has expanded by about 500 million hectares, or about 60 percent of the size of the contiguous United States. “We cannot keep doing that,” she stressed. Water withdrawal is a serious issue as well, she added. (WRI’s environmental impact analysis was based on EIA [2012]; EPA [2012]; FAO [2011, 2012a]; Foley et al. [2005]; Houghton [2008]; IEA [2012]; and Lindquist et al. [2012].)

Production Versus Consumption Strategies for Sustainably Closing the Food Gap

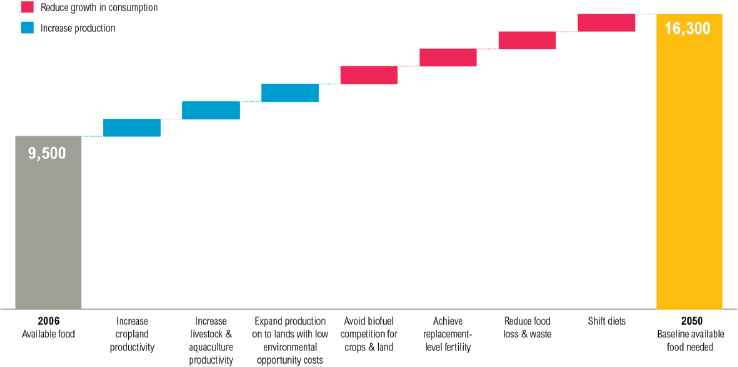

According to Ranganathan, WRI recognizes that there is no “silver bullet” for meeting the above needs. She asserted that, although dietary shift may be a “shinier silver bullet” than many of the others, “we need

all solutions on the table,” including strategies for increasing production sustainably and other strategies for reducing growth in consumption (see Figure 4-4). Building on what several previous speakers had mentioned, she briefly described several examples of both types of strategies.

Increasing Production

According to Ranganathan, sustainable production solutions include, first, sustainably boosting yields through crop breeding. She called attention to “the other GM,” meaning Gregory Mendel and classical breeding, and highlighted the potential of modern genomics to accelerate conventional crop breeding. In addition, she stressed, there are significant opportunities to increase the productivity of orphan crops, which cover large portions of land, particularly where poor farmers live.

As a second production strategy, Ranganathan pointed to improving soil and water management. As examples, she cited bringing forests back into agricultural systems and rainwater harvesting.

The third production strategy identified by Ranganathan is restoring degraded land and using it to produce food. Depending on one’s definition of degraded land, there may be 1 billion hectares of degraded lands globally, she observed.

NOTE: Values depicted by bars are global crop production in trillions of kilocalories.

SOURCES: Presented by Janet Ranganathan on August 1, 2018; Ranganathan et al., 2016.

In addition to boosting crop yields, Ranganathan continued, another set of solutions pertains to sustainably increasing livestock productivity. Even though most of the research on intensification has focused on crops, she pointed out, about twice as much land is devoted to livestock production. In her view, there are many promising opportunities to increase both pastureland and livestock productivity—especially with ruminants, and beef in particular—not necessarily in the United States but in developing countries. The same is true, she suggested, for wild fish. While she acknowledged that wild fish catch will probably have to be reduced to allow overexploited fisheries to recover, there are again, she argued, good opportunities to increase the productivity and sustainability of aquaculture.

Reducing Consumption

According to Ranganathan, strategies for reducing consumption include, first, as previous speakers had mentioned, reducing food loss and waste. She noted that globally, about one-third of food by weight and about one-quarter of food by calories is lost between farm and fork. She reported that WRI is developing a protocol for measuring food loss and waste, based on the premise that “what gets measured gets managed.” In addition, the Institute is building a coalition of leaders who have made commitments to reducing food loss and waste by 50 percent by 2030 and to sharing lessons learned. Known as Champion 12.3 (named after the Sustainable Development Goal and target devoted to reducing food waste), the coalition includes leaders and heads of supermarkets, companies, states, and countries. Ranganathan observed that if food waste were a country, it would rank third in GHG emissions behind China and the United States. “Just think about that,” she said. “It is wasted water. It is wasted land. It is wasted greenhouse gas emissions. And it is wasted money. We have to get on that one.”

Ranganathan identified as a second consumption strategy achieving replacement-level fertility. She sees this as an important opportunity in sub-Saharan Africa in particular, where the fertility rate has been about 5 births per woman over the past 5 years and is predicted to drop to about 3.2 by 2050. “We can speed that up,” she argued, by doing things that should be done regardless, such as keeping girls in school, providing access to reproductive health services, and reducing infant and child mortality.

Another consumption strategy cited by Ranganathan is reducing demand for biofuel crops. She pointed out that a target of 20 percent biofuel in the energy system by 2050, an actual target in some countries, would require almost the entire biomass harvest of 2000. “Think about the extraordinary potential for competition that would create between food and fuel,” she observed. “That is something we must deal with.” (See Chapter 3 for a summary of Wilde’s discussion of biofuel and its influence on prices.)

Finally, Ranganathan highlighted shifting diets as another consumption strategy for achieving a sustainable food future, as Springmann and others had discussed. She noted that animal-based foods are generally more land-, water-, and GHG-intensive to produce relative to plant-based foods. For every food calorie generated, she elaborated, ruminant meat requires more feed and land input and emits far greater amounts of GHGs compared with other foods. According to Ranganathan, efforts to date to shift diets have focused on education, information, and abstinence. While she believes that these approaches are important, she asserted that they are not enough. She spent the remainder of her talk discussing what WRI has learned from the private sector about shifting behavior, as summarized below.

Later, during the discussion period, Ranganathan clarified that while she was not convinced that information provided in the DGA directly influences what foods people order or buy, she believes it does in fact have a significant influence on the food manufacturing and food services sectors.

Strategies for Shifting Diet: Lessons from the Private Sector

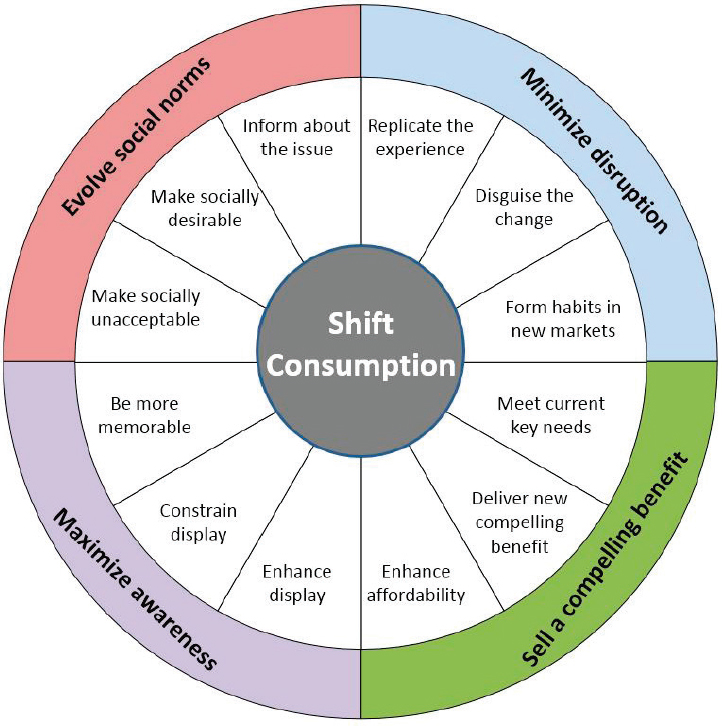

“The private sector knows how to influence people’s consumption choices,” Ranganathan said. Rather than examining how taxes, subsidies, and other governmental mechanisms can influence people’s food choices, WRI chose to examine how the private sector uses marketing and behavioral science to influence people’s choices.

Four Common Strategies

In an analysis of more than 20 successful consumption shifts that have already occurred in the consumer goods sector, Ranganathan and colleagues identified four common strategies that work in concert.

The first is to minimize disruption. According to Ranganathan, this is what companies marketing fake meat are trying to do by providing something that looks like regular meat and can be barbequed or otherwise prepared like regular meat. This is also why some merchants place soy milk in the refrigerated section of the market where people habitually go to get their milk, even though soy milk does not need to be refrigerated.

The second strategy is to sell a compelling benefit. In other words, Ranganathan explained, do not tell people why a product is good for them or bad for the environment and hope that they will shift to something else. Rather, think about what consumers actually want, such as taste and affordability.

The third strategy is to maximize awareness, which Ranganathan characterized as “a tried and tested strategy by the private sector.” The products marketers want to sell the most, for example, are placed at the end of an

aisle in a supermarket or at the top of a menu in a restaurant. Things they do not want consumers to purchase because those products have a lower profit margin are placed on lower supermarket shelves.

Fourth is evolving norms. Ranganathan cited just one example: “If you think about the last time you saw a man in public cooking food, he was probably cooking a beef burger on a barbeque.” She referred to Macdiarmid’s earlier discussion of other examples of social norms and encouraged more thinking about how to evolve them to favor more sustainable food choices, such as plant-based rather than animal-based food.

Case Study: Low-Alcohol Beer

Around 2000, the UK government stated that it wanted to remove 1 billion units of alcohol from the market, out of concern about binge drinking and alcoholism. Thus, Ranganathan explained, the government challenged the beverage sector to help shift consumers from drinking beverages with high to those with low alcohol content. She recounted how Molson, which makes Carling, accepted the challenge because it had a low-alcohol alternative and did not want to lose market share. But the company faced a number of barriers, she observed: people did not want low-alcohol beer, they did not like the taste of it, and it was usually located in the low-traffic, “low-alcohol” section of supermarkets. To get around these barriers, Ranganathan explained, Molson took a number of actions, all of which aligned with those presented in WRI’s shift wheel (see Figure 4-5): it masked the bitter taste by creating ginger and lime flavors (i.e., it minimized disruption by disguising the change); it positioned the new product around the benefit of a lower-carb refreshment, making no mention of its alcohol content (i.e., it sold a compelling benefit); and it gave the product a new name, Carling Zest. At the same time, Ranganathan added, the UK government increased the excise tax on high-alcohol drinks and reduced it on low-alcohol beer, so the price of the new product went down. Instead of passing that savings on to consumers, Molson passed it on to retailers, increasing the profit margin from selling this brand, thus incentivizing the retailers to give Carling Zest a more prominent shelf space (i.e., maximizing awareness). As a result of these actions, according to Ranganathan, this was a successful rebranding campaign.

Ranganathan described how Unilever did much the same thing to shift people from cod-based to pollock-based fish fingers, that is, from an overfished to a more prevalent species, and in the process to reduce its raw material costs. The barriers to this strategy, Ranganathan observed, were a strong association between fish fingers and cod; an assumption that pollock does not taste as good as cod; and the gray, not white, color of pollock, which was off-putting to consumers. She explained that by positioning

SOURCES: Presented by Janet Ranganathan on August 1, 2018, modified from Ranganathan et al., 2016.

the pollock-based product around the health benefit of its higher omega-3 content (i.e., selling a compelling benefit) and by passing on some of the savings in raw material costs to retailers, the company encouraged retailers to promote and display the new fish fingers (i.e., maximizing awareness).

Strategies for Shifting Diet: Lessons from the Food Services Sector

In addition to its study of the retail sector, Ranganathan continued, WRI has been studying consumer behavior in the food services sector. She argued that, with respect to encouraging consumers to choose more plant-based foods, the food services sector may be an easier target than the retail

sector for three reasons. First, she observed, in the United States, as much money is spent on food consumed outside as inside the home. Second, she pointed out that the incentives of the food services sector are aligned with the objective of shifting diets because it sells meals, not foods. Third, she noted that habits formed outside the home are often brought back into the home.

Ranganathan reported that WRI created its Better Buying Lab with a group of food service companies to experiment with ways of shifting food choices in the United States and the United Kingdom. She explained that the lab generates ideas, tests those ideas with the food service companies, and then shares more broadly what has been learned. Currently, she said, the lab is focused on three areas: (1) transforming how the food industry communicates about plant-based foods, (2) popularizing dishes rich in plants, and (3) identifying the right environmental targets and metrics. She then discussed the first two of these efforts in more detail.

Language and Framing: Transforming How the Food Industry Communicates About Plant-Based Foods

Ranganathan asked workshop participants to imagine being presented at a restaurant with a menu containing an entrée described as “baked squash with rice and grits.” Then, she asked them to imagine being presented with a menu describing that same entrée as “roasted butternut squash with sweet and spicy coconut rice and fresh Thai basil.” Which is more attractive to you? she asked.

It is not just language but also positioning on a menu that can be used to shift behavior, Ranganathan continued. She described a study that WRI conducted in collaboration with the London School of Economics that involved comparing menus containing a separate box for vegetarian dishes (“vegetarian” menu) with menus in which vegetarian dishes were included in the main section of the menu (“control” menu). She reported that, among 760 study participants in the United Kingdom, 13.4 percent ordered vegetarian entrées from the control menu, compared with only 5.9 percent who ordered from the vegetarian menu (Bacon and Krpan, 2018).

Ranganathan described another study, not conducted by the Better Buying Lab, in which researchers compared four ways of framing the same vegetable: indulgent (e.g., “twisted garlic ginger butternut squash wedges”), basic (“butternut squash”), healthy restrictive (“butternut squash with no added sugar”), and healthy positive (“antioxidant-rich butternut squash”) (Turnwald et al., 2017). The study revealed that using indulgent language resulted in significantly more people selecting a vegetable relative to when that same vegetable was described using either basic, healthy restrictive, or healthy positive language. “Language, I think, does matter,” Ranganathan

concluded. At the same time, however, she cautioned against overselling this claim, and she described this as a nascent but fertile research area.

Power Dishes: Popularizing Dishes Rich in Plants

A second strategy being tested at the Better Buying Lab is to popularize dishes rich in plants by increasing the number of plant-based “power dishes,” defined as dishes that are prevalent on menus in mainstream restaurants. Currently, Ranganathan reported, only one vegetarian dish—the ubiquitous “veggie sandwich/wrap”—is among the top 25 most prevalent dishes on menus in U.S. restaurants. She described how the lab has been working on introducing three additional vegetarian power dishes: a blended burger (30 percent mushroom, 70 percent beef), a veggie bowl, and an avocado club sandwich. Given that 1 billion beef burgers are sold in the United States annually, she observed, even if only 30 percent of the beef in each of those burgers was replaced with mushrooms, in terms of GHG emissions that would be like taking 2.3 million cars, or about the total number of cars in San Diego, off U.S. roads.

Supply Chain Greenhouse Gas Emissions

In closing, Ranganathan mentioned briefly that while many food service companies have made commitments to GHG reduction, most of their efforts are centered around transportation and energy. She stated that WRI is also working to encourage them to think about the GHG emissions resulting from their food supply chains. She observed that shifting consumers to more plant-based foods can be an effective GHG reduction strategy as well.

THE CASE FOR NUTRITION-SENSITIVE VALUE CHAIN INTERVENTIONS: WHAT GETS MEASURED GETS IMPROVED

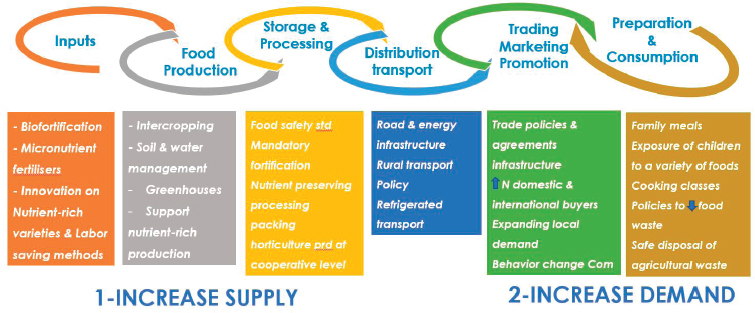

While most of the workshop discussion on actions that can support sustainable diets revolved around production versus consumption strategies, Maha Tahiri, former food industry executive, addressed the challenges and opportunities for achieving sustainable diets through a different lens: nutrition-sensitive value chain (NSVC) interventions. Referring back to Fanzo’s earlier remarks about policy making (see Chapter 2), she suggested that NSVCs are something policy makers and the private sector should take into account.

Historically, Tahiri observed, most food chain interventions have been aimed at increasing yield and the well-being of farmers. She explained how the concept of an NSVC, with its focus on nutritional outcomes, not just economic value, emerged about 10 years ago based on the premise that “what gets measured gets improved.” She noted that, in the NSVC

definition articulated by an FAO-hosted Rome-based Agencies4 working group on NSVCs (FAO, 2017b; see Box 4-2), she was particularly struck by its focus on the whole value chain, from input, through preparation, to consumption.

Rationale for the NSVC Approach

Tahiri called attention to a handful of studies reporting that traditional interventions, such as food fortification, complementary feeding, and promotion of breastfeeding, are not enough to achieve global nutrition targets. First, she pointed to a study conducted by The Lancet’s Maternal and Child Undernutrition Group as being particularly important (Bhutta et al., 2008). Among 36 countries representing 90 percent of the global malnutrition burden, the researchers concluded that implementation of evidencebased interventions would not achieve global targets. Tahiri then cited a follow-up study in which Bhutta and colleagues (2013) demonstrated that implementing 10 evidence-based nutrition-specific interventions, including breastfeeding, fortification, and community interventions, with 90 percent coverage would reduce deaths among children younger than 5 years by only 15 percent and reduce stunting by only 20 percent. The authors concluded that nutrition interventions should be combined with nutrition-sensitive approaches that address the underlying determinants of malnutrition, such as women’s empowerment, education, employment, social protection, and

___________________

4 The Rome-based agencies include FAO, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the World Food Programme (WFP), and the Bioversity International.

safety nets. Lastly, Tahiri highlighted a review paper on the impacts of agriculture on nutrition (Webb and Kennedy, 2014), in which the authors analyze 10 well-implemented interventions and conclude that the “empirical evidence for plausible and significant impacts of agriculture on defined nutrition outcomes remains disappointingly scarce.” Tahiri pointed out, however, as the authors do, that the absence of evidence is not the same as evidence of absence. Agriculture and nutrition are both very large domains, she explained, and unless an analysis is more specific, it makes sense that significant correlations would not be detected.

Strategies for NSVC Intervention

Tahiri identified as one particularly positive feature of NSVCs that they make it possible to divide the complex food system into different parts and visualize, depending on the situation (i.e., increased demand versus increased supply), how an intervention at any point along the value chain could enhance nutrition (see Figure 4-6). In this way, she posited, they help people formulate questions in a more expansive way, including how to act in the interest of sustainability.

As an example of a possible NSVC intervention in a situation of high demand and inconsistent supply, Tahiri mentioned labor-saving methods at the input stage, which would also have sustainability implications in the sense that such a strategy would mean more time for mothers to care for their children. She cited refrigerated transport at the distribution/transport stage as another example of an NSVC intervention in such a situation that would also have implications for sustainability. In contrast, in a situation of

NOTE: N = population; prd = product; std = standard.

SOURCES: Presented by Maha Tahiri on August 1, 2018, modified from FAO, 2017b.

high demand and consistent supply, she suggested that the focus probably should be on food safety. In a situation of demand constraint and consistent supply, she stated that interventions would be targeted at the trading/marketing/promotion stage of the value chain. Finally, she observed that in a situation of demand constraint and inconsistent supply, interventions would probably need to be applied all along the chain.

NSVC Interventions: An Example and Proof of Concept

As an example of an NSVC, Tahiri described work conducted by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) in Rwanda and Uganda to increase the availability of, access to, and demand for nutritious beans (Mazur et al., 2009). She noted that beans are very important in both countries. She reported that the researchers conducted field trials with new varieties of beans, training farmers on the spacing of rows and other production techniques. They also trained farmers on anaerobic storage and other postharvest technologies. In addition, they worked with the farmers to help them understand the market and to sell their beans collectively. Tahiri pointed out that when the farmers sold individually, only about 10 percent would actually sell their beans on any given day, whereas when they sold collectively, more than 81 percent were able to sell their beans. Finally, Tahiri said, the researchers also worked with the farmers to improve their negotiation skills and increase demand from other countries, namely South Sudan and Kenya. In sum, she explained, they examined all aspects of the value chain to see where they could make improvements. However, she cautioned, this was not a controlled study, so it was not possible to say that the interventions were any more effective than traditional interventions.

Tahiri said she was unaware of any controlled studies of NSVC interventions. What she characterized as the “best” she could find was what she considers a proof-of-concept study conducted in North Senegal (Le Port et al., 2017). She described how this study involved a value chain that already existed—a local dairy factory, Laiterie du Berger—that had been receiving milk from its network of seminomadic, pastoralist dairy farmers, but on an irregular basis. Tahiri explained that the intervention involved a yearlong exchange between the farmers and the factory, whereby the farmers delivered a constant supply of milk to the factory 5 days per week in return for a fortified yogurt produced from that milk that the farmers would then feed to their children. She added that the study was conducted while a behavioral change communication campaign related to fortified products was being implemented nationwide. The researchers found that after 1 year, the prevalence of anemia among children aged 24 to 59 months had declined from 80 percent to 60 percent. The impact was greater on boys than on girls. Although this was not a case-control study, Tahiri said, it was “what

I would say is really good proof of concept of a nutrition-sensitive value chain intervention.”

Final Remarks

Tahiri concluded by highlighting what she considers to be key factors in the success of NSVC interventions. She identified as one of the most important that there be a clear definition of the nutrition problem, and therefore of the nutrition goal. In addition, she called for an expansive search for creative solutions that can be applied locally. Next, she highlighted coordination of the whole chain as key, although she acknowledged that this sometimes is not possible; for example, when no transportation is available.

Tahiri cited adding value to all actors along the value chain as another key factor driving success and as one of the keys to the success of the North Senegal dairy intervention: Laiterie du Berger received a constant supply of milk, and the herders received a fortified yogurt for their children. Referring to the philanthropic work done by many companies in Africa, India, and elsewhere, she pointed out that “all actors along the value chain” include the private sector. She encouraged more engagement of the private sector—from large, vertically integrated, multinational companies to individuals who transport, store, aggregate, or sell food.

Yet another key factor in success, Tahiri stressed, is to adopt a “consumer first” approach, which she believes is the best way to increase or create demand. Even when people say they want to have sustainable products, she noted, consumer research has shown that when consumers are actually making a purchase, they do not buy a product unless there is something specific and “close to home” about it that they can embrace.

Finally, Tahiri underscored the need to focus on influencing policy. Specifically, she pointed to the importance of elevating nutrition in the agenda.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR INTEGRATING SUSTAINABILITY AND DIETARY GUIDANCE

Barbara Schneeman, University of California, Davis, who served on a National Academies committee examining the process for establishing the DGA (NASEM, 2017), addressed how sustainability could be integrated into the DGA. She used that committee’s report, Redesigning the Process for Establishing the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, as the basis for her presentation. She characterized it as particularly useful for this purpose because the committee did such a thorough job of examining the evolution of the DGA and the methodology used to establish the guidelines. The committee, she explained, identified three essential functions, or phases, currently carried out by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC),

working in collaboration with staff from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and USDA: (1) strategic planning, (2) analysis, and (3) synthesis/interpretation. Schneeman did not think it necessary, for the purposes of this talk, to go into detail on the redesign of the DGA cycle proposed by the National Academies committee (i.e., a 5-year cycle between releases of subsequent DGAs). She did emphasize, however, the committee’s recognition that each phase requires the right expertise and right investment of time and resources. Therefore, she reported, the committee proposed that different DGA committees be responsible for each of the three essential phases. Schneeman went on to consider how sustainability could be integrated into each of these phases through the work of the proposed DGA committees and in other ways.

Integrating Sustainability into Dietary Guidelines for Americans Strategic Planning

In general, the National Academies committee encouraged more strategic planning across DGA cycles and a longer-term look at development of the guidelines. Specifically, the committee proposed that a Planning and Continuity Group “provide the secretaries of USDA and HHS with planning support that assures alignment with long-term strategic objectives spanning multiple DGA cycles, identify and prioritize topics for the [Dietary Guidelines Scientific Advisory Committee] to evaluate in subsequent DGA cycles, and oversee monitoring and surveillance for new evidence.” Schneeman clarified that this planning group would not be involved with developing or evaluating evidence, but with determining whether there is evidence suggesting that a topic might be “ready for prime time.”

In the context of how sustainability might be integrated into the strategic planning phase, Schneeman identified two key opportunities: first, determining how sustainability relates to the purpose of the DGA, and second, delineating sustainability topics to be addressed in subsequent cycles.

Determining How Sustainability Relates to the Purpose of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans

The National Academies committee identified multiple statements about the purpose of and audience for the DGA, Schneeman reported, leading it to urge continuity and clarity around these statements. In fact, she said, the committee proposed a singular purpose statement aligned with wording in the legislation that established the DGA cycle (i.e., the National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act): “The purpose of the DGA is to provide science-based ‘nutritional and dietary information and guidelines for the general public’ that form the basis for ‘any federal food, nutrition,

or health program.’” Schneeman added that the committee proposed that the audience for the DGA be the general public and that the goals of the guidelines be to promote dietary intake that helps improve health and reduce the risk of chronic disease and to provide the federal government with a consistent approach for nutrition policy and messaging. Although sustainability is not an explicit part of the proposed purpose statement, she asserted that there would be ways to accomplish this.

Delineating Sustainability Topics to Be Addressed

Regarding the identification and prioritization of topics to be evaluated during subsequent DGA cycles, Schneeman continued, the National Academies committee divided criteria for topic selection into three categories: topic identification, topic selection, and topic prioritization. She explained that the first two categories are areas in which there probably should be nongovernmental stakeholder as well as government input. In contrast, the committee identified topic prioritization as a task for the proposed Planning and Continuity Group. As with the purpose statement, Schneeman added, sustainability was not incorporated as an explicit criterion for any of the three categories of criteria. Criteria for topic identification, she elaborated, focus more on relevance to diet, nutrition, and health. While the criteria for prioritization suggest cost-effectiveness studies, their focus is more on public health urgency and the availability of evidence-based intervention. In Schneeman’s opinion, again, there clearly is an opportunity to consider how sustainability could be integrated into this scheme. She mentioned that HHS and USDA asked for comments on topics during the last DGA cycle, so there does appear to be some interest in opening the process up to suggestions. However, she was unaware of whether any sustainability-related topics were advanced. She stressed that in the future, depending on the topic(s) chosen, the relevant expertise will need to be brought to bear, either through membership of the Planning and Continuity Group or through any subcommittees that are formed. Either way, she said, “that expertise needs to be part of the process.”

Challenges to Integrating Sustainability into Dietary Guidelines for Americans Strategic Planning

In Schneeman’s opinion, integrating sustainability into DGA strategic planning presents an opportunity, but also challenges. She identified as a key challenge understanding the objective for incorporating sustainability. Is it to justify the recommendations? Is it to consider the environmental impacts of dietary shifts? Or is it to see whether the recommendations are feasible given current economic and agricultural capacity? Schneeman

observed that all of these questions had been touched on during this workshop. In addition, she pointed to a 1998 WHO/FAO report, Preparation and Use of Food-Based Dietary Guidelines, which emphasizes the importance of addressing such issues as economic and agricultural capacity when developing food-based dietary guidelines (WHO and FAO, 1998).

Integrating Sustainability into Dietary Guidelines for Americans Analysis

According to Schneeman, the types of evidence currently used to develop the DGA include original systematic reviews conducted with support from USDA’s Nutrition Evidence Library (NEL); existing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reports that are relevant and that meet the process criteria; descriptive data analyses, such as intakes of food and nutrients (e.g., from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey’s [NHANES’s] What We Eat in America); and, increasingly, food pattern modeling analyses aimed at determining what kind of food patterns meet the DGA recommendations. The National Academies committee proposed the use of technical expert panels (TEPs) to provide independent expertise during the analysis phase. Schneeman explained that a TEP could be assembled to help with systematic reviews, or if there were a specialized topic relating to a certain aspect of sustainability, a TEP could be assembled to assist with the technical review of that topic. In Schneeman’s opinion, supplemental expertise in food pattern modeling and descriptive data analysis could become critical if sustainability were incorporated as a factor.

In Schneeman’s opinion, probably the most important challenges to integrating sustainability into the analysis phase of the cycle are defining the topics and research questions that can be addressed with systematic reviews and identifying the descriptive data analyses that are most relevant. As she had mentioned previously, the NHANES is one of the primary sources currently used for descriptive data analysis. But what is the most relevant tool from a sustainability point of view?, Schneeman asked. And how should food pattern modeling be considered in relation to sustainability? Given that food pattern modeling is used to see what patterns meet the DGA recommendations, does sustainability now need to be built into the way these models are constructed? Again, Schneeman stressed, the TEPs would need to include experts with knowledge in these areas.

Integrating Sustainability into Dietary Guidelines for Americans Synthesis and Interpretation

Schneeman observed that work conducted during the third phase, synthesis and interpretation, is what most people associate with the current DGAC. She noted that the National Academies committee proposed

renaming the DGAC the Dietary Guidelines Scientific Advisory Committee (DGSAC) to emphasize the science, as it is during this phase that the DGAC synthesizes, interprets, and integrates the data and evidence across studies to develop conclusions and recommendations. In addition, the DGAC identifies new analyses that might be needed, topics on which more evidence is needed, and topics for future DGA cycles, as well as research recommendations. The main task, though, according to Schneeman, is to produce a scientific report for the secretaries of HHS and USDA to serve as a foundation for the DGA Policy Report.

Schneeman explained that integrating sustainability into this third phase would involve, again, including experts who can provide relevant knowledge and context for a review of the evidence on topics identified as relevant for consideration in the DGA. She noted the report of the National Academies committee (NASEM, 2017) refers to an earlier report on the selection process for DGAC members, and she pointed out that those same criteria would have to be applied to the selection of sustainability experts for the DGAC (or the renamed DGSAC).

The main challenge to integrating sustainability into the DGA synthesis and interpretation phase, as Schneeman sees it, is that the process for nominating and selecting DGAC (DGSAC) members with the relevant sustainability expertise would depend on having identified specific areas of sustainability to be considered in that cycle.

Final Remarks

The opportunities discussed by Schneeman for integrating sustainability into the three key phases of the DGA process are summarized in Table 4-1. She noted that she had not discussed the final phase, federal review and update, which is what leads to publication of the DGA Policy Report. In her opinion, if there is transparency in the three earlier phases regarding the integration of relevant sustainability topics, this final phase “takes care of itself.”

Schneeman’s take-home message was that to integrate sustainability into the DGA, it will be necessary to clarify the relationship between sustainability and the purpose of the DGA. Another key challenge, she suggested, will be to reexamine the resources for the three phases (strategic planning, analysis, and synthesis/interpretation) to see how they might need to be shifted so that sustainability can be addressed.

Finally, Schneeman mentioned that one of the recommendations of the National Academies committee was to consider the emerging importance of systems approaches. Specifically, recommendation 7 of the committee’s report (NASEM, 2017) was: “The secretaries of USDA and HHS should commission research and evaluate strategies to develop and implement

TABLE 4-1 Opportunities to Integrate Sustainability into the Different Phases of the National Academies’ Proposed Dietary Guidelines for Americans Process

| Phase | Opportunities |

|---|---|

| Strategic Planning |

|

| Analysis |

|

| Synthesis and Interpretation |

|

| Federal Review and Update |

|

NOTE: DGA = Dietary Guidelines for Americans; DGSAC = Dietary Guidelines Scientific Advisory Committee.

SOURCE: Presented by Barbara Schneeman on August 1, 2018; reprinted with permission.

systems approaches into the DGA. The selected strategies should then begin to be used to integrate systems mapping and modeling into the DGA process.” The committee recognized that this would not “happen overnight,” Schneeman said, because understanding how a systems approach can be helpful requires investment. In her opinion, a systems approach may also be a way to integrate sustainability into the DGA.

DISCUSSION

In the discussion following Schneeman’s presentation, she, Springmann, Macdiarmid, Ranganathan, and Tahiri participated in an open discussion with the audience, summarized here.

Integrating Sustainability Components into the Dietary Guidelines for Americans

There was considerable discussion around sustainability and the DGA, beginning with Drewnowski’s reminder that there are four dimensions of sustainable diets according to the FAO definition: (1) nutrition and health, (2) economic, (3) social and cultural, and (4) environmental. He expressed disappointment that the DGA have mentioned only the first of these. He stated that, to its credit, the DGAC has mentioned affordability, financial burden, and health equities in its work; however, the final documents have made no reference to these components, nor has there been any reference to societal value or food acceptance. He pointed out, for example, that among the current USDA healthy food patterns, the Mediterranean-style pattern is more expensive than the vegetarian pattern. He called for the incorporation of affordability, as well as the societal value and environmental components of sustainability, into future DGA.

In response, Schneeman reflected on the different ways in which people think about the objective of integrating sustainability into the DGA and suggested that probably everyone can bring something to the table. While acknowledging that it would be difficult with the current cycle, she encouraged the audience, “If the topics start to emerge and we have agreement on how sustainability relates to the purpose of the dietary guidelines, then we have a way to start thinking about how [to] build that into the dietary guidelines going forward.”

Peter Lurie, Center for Science in the Public Interest, Washington, DC, and Food Forum member, suggested reframing Drewnowski’s question in a slightly different way. Instead of asking why not, he proposed asking what is feasible. What is the likelihood that sustainability can be integrated into the DGA? Or which elements of sustainability that Drewnowski had laid out are most likely “to fall on receptive ears”? (For more detail on Drewnowski’s exposition of the four dimensions of sustainability, see Chapter 2.)

Schneeman said she was unaware of which topics, other than B-24 (nutrition for children up to 24 months), will be considered in the next cycle of the DGA. She pointed to B-24 as a good case study of what it takes to bring a topic forward in a way that is suited to and positioned for the DGA process. She also commented on how the National Academies committee believed it would be helpful to move away from the practice of reviewing every topic during every DGA cycle, as there are some areas in the DGA that have not changed for 20 or 30 years (NASEM, 2017). This does not mean, she clarified, that those topics should never be reviewed, but that having a longer cycle of review for some topics would open up the opportunity to explore new topics.

Tahiri added that consumer research could help inform specific economic or social and cultural topics to include in the DGA process. In other words, it could reveal what American consumers want included in the DGA.

Rose pointed to the fact that there are two reports—the DGAC report and the final DGA. He views this as a gap given that the last DGAC report contained a chapter on sustainability that was excluded from the final DGA. He asked whether it would be possible to go back to the practice of the DGAC’s issuing the final DGA without that final report being filtered through federal oversight.

Schneeman clarified that, even as far back in 1990, when she first served on the DGAC, the DGAC report went to the secretaries of HHS and USDA, who would then release the final DGA. The difference, she noted, was that the DGA at that time was a 20- or 30-page consumer pamphlet. Although its report contained a great deal of scientific detail and justification regarding any recommended DGA revisions, the DGAC was told that any new language it was recommending should be written at an eighth-grade level. Not until the 2005 DGA, Schneeman observed, was it realized that it made no sense to produce a consumer bulletin through the DGAC; rather, the DGAC’s strength was conducting a scientific evaluation and examining the evidence supporting the recommendations in the DGA or any revisions thereof. Thus, she continued, it was decided that the DGAC report should serve a scientific advisory purpose and that the DGA would no longer be a consumer bulletin, but a report aimed at policy makers. It would then be the responsibility of those policy makers to develop a consumer brochure. Schneeman added that today, a federal working group reviews educational materials issued by HHS or USDA to ensure that they are consistent with the DGA. Regarding the issue of sustainability, she noted that this issue sparked a great deal of controversy in the last DGA cycle. She referred again to the report of the National Academies committee and a recommendation therein relating to the responsibility of any advisory committee that, in the process of its work, becomes aware of an issue it views as important but was not chartered to address (NASEM, 2017). Maybe that committee’s job, she suggested, is to make sure that this issue is brought forward such that it will be addressed in the future, and that this, in fact, is what happened with sustainability in the last DGA. “Why are we having this discussion today?” she asked. “It is because of the controversy around how to include sustainability. Think of it as a success.”

Claudia Hitja, USDA, asked whether any country had successfully integrated sustainability into its national dietary guidelines. Springmann directed Hitja to an FAO/Food Climate Research Network (FCRN) report titled Plates, Pyramids, Planet: Developments in National Healthy and Sustainable Dietary Guidelines (Fischer and Garnett, 2016).

Country-Level Versus Local Data

Drewnowski pointed to the correlation between the distribution of plant protein consumption across Seattle and socioeconomic status. “People who consume plant proteins are the ones who consume salad and live in nice houses on the waterfront,” he observed. “When looking at grossly aggregated data by country, you really are losing track of the very small geographic distinctions.” He asked Springmann how useful it is to look at country-level data.

Springmann agreed that country-level analyses examine only general trends, such as trends in what people consume or what they are thought to be eating. But that is the intent of such analyses, he asserted: to illustrate those generalities and tease out country differences, not to inform local understanding. “There are discussions to be had at any level, I suppose,” he commented.

The Evidence for Successful Dietary Shifts

Curious about whether there is any evidence to suggest that sustainable diet goals will be achievable, Afshin pointed out that no country has been successful at reducing the prevalence of overweight and obesity over the past 30 years. In addition, he noted that the consumption of nuts has increased by only 2 grams over that same period. “Is it possible to increase that by 20 grams over the next 20 years?” he asked. “Has any country been able to achieve at least any of these [dietary change] scenarios over the last few years?”

At the country level, Springmann responded, this probably has not been accomplished. However, he stressed, there is evidence that specific dietary interventions can be successful. As an example, he mentioned weight loss studies conducted by Oxford University researchers demonstrating that overweight and obesity can be reduced, although success requires intensive resources and follow-up. In addition, he cited an effort in North Karelia, Finland, to reduce the intake of saturated fats, which he characterized as “pretty successful.” And he suspects that there have been other, similarly successful small-scale interventions involving broad dietary changes. He also referred to an analysis of the effect of GHG taxes on food consumption. While the analysis predicted that taxing food according to its GHG emissions could influence food consumption, diets would probably not change significantly. Thus, he emphasized, “you really need a multitude of different interventions.” He stressed, too, that the lack of evidence of large-scale, country-level changes does not mean there should be no efforts to achieve such changes. “I think we are called to action on all dimensions,” he argued.

Tahiri suggested that by also examining socioeconomic changes, as Drewnowski had emphasized, one might in fact be able to detect country-level dietary shifts.