1

Introduction

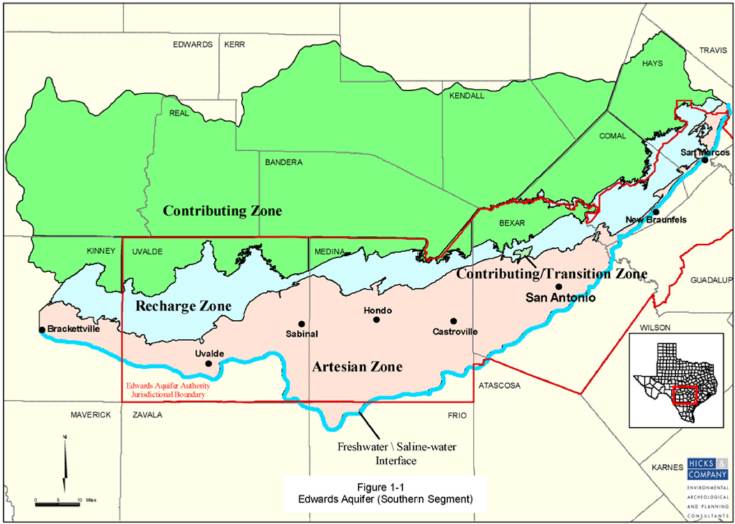

South-central Texas is home to one of the most productive karst aquifers in the world—the Edwards Aquifer. The Edwards, which covers an area of approximately 3,600 square miles (Figure 1-1), is the primary source of drinking water for over 2.3 million people in San Antonio and its surrounding communities. In addition, it supplies irrigation water to thousands of farmers and livestock operators in the region, which can account for as much as 30 percent of the total water pumped from the system each year. The Edwards Aquifer has extremely high-yield wells and springs, which respond quickly both to rainfall events and to water withdrawals for irrigation and municipal supply. The region suffers periodically from droughts, with the most recent being from 2010 to 2014. There is a risk that future droughts could reduce flow in the Edwards Aquifer and its major springs (Comal Springs in New Braunfels and San Marcos Springs in San Marcos) to a level low enough to put the aquifer and spring ecosystems in peril.

Comal Springs and San Marcos Springs and their river systems house several plants and animals found nowhere else in the world. Eight of these species are listed as threatened or endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA): the fountain darter, the San Marcos gambusia (which is presumed extinct), the Texas blind salamander, the San Marcos salamander, the Comal Springs dryopid beetle, the Comal Springs riffle beetle (CSRB), the Peck’s Cave amphipod, and Texas wild rice. To protect these species, the Edwards Aquifer Authority (EAA) and four other local entities created a 15-year Habitat Conservation Plan. The EAA is a regional government body tasked with managing domestic, industrial, and agricultural with-

drawals from the Edwards Aquifer while maintaining spring flows at quantities that can support the listed species. The EAA implements the Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP), which the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) finalized and approved in 2013 after a years-long development process. Months later the EAA requested the input of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) to review the plan and its implementation. This report is the third and final product of a three-phase National Academies study to provide advice to the EAA on various scientific aspects of the HCP that will ultimately lead to improved management of the Edwards Aquifer. The National Academies’ first report (NRC, 2015) provides a comprehensive description of the hydrology of the Edwards Aquifer and its spring systems. The reader is referred to Chapter 1 of that report for in-depth information on these topics. A very cursory summary of Edwards Aquifer hydrology and ecology is presented here, followed by discussion of the HCP.

HYDROLOGY OF THE EDWARDS AQUIFER

As shown in Figure 1-1, the Edwards Aquifer has contributing and recharge zones to the north, and pumping and artesian wells largely in the south. The contributing zone is where rain falls and is directed by streams toward the recharge zone. In the recharge zone, precipitation percolates and flows into the groundwater to replenish the aquifer. Groundwater is under high-pressure conditions in the artesian zone, such that groundwater flows to the land surface in the form of springs and seeps. At least six springs occur within the artesian zone, including the two largest in Texas, the San Marcos and Comal springs. The Edwards Aquifer is characterized by karst features, such as fractures, caves, and sinkholes, which transport large volumes of groundwater through the system on the order of several days.

Annual precipitation across the region ranges from about 22 inches in the west to over 34 inches in the east. Mean annual precipitation for San Antonio (1934–2013) was approximately 30.38 inches, although this varied annually by as much as 20 inches. Indeed, it is not unusual for the Edwards Aquifer region to experience periods in excess of 40 inches of rain per year separated by droughts. The most significant drought, referred to throughout this report as the Drought of Record, occurred from 1950 to 1956, during which time precipitation was well below the mean annual average for six consecutive years. Evapotranspiration (unhindered vegetative rate) is similarly variable across the region, ranging from more than 60 inches per year in the west to 30 inches per year in the east (Scanlon et al., 2005). Over the long term, precipitation in the region is expected to decrease and evapotranspiration is expected to increase (Loáiciga et al., 2000; Mace and Wade, 2008; Darby, 2010), which, combined with an anticipated population increase, will cause the Edwards Aquifer to be more stressed in the future.

Variations in climate in the Edwards Aquifer region are reflected in the aquifer’s water budget. From 1934 to 2016, the median annual recharge was 557,800 ac-ft1 with a range from 43,700 ac-ft during the Drought of Record to 2,486,000 ac-ft in 1992 (Blanton and Associates, 2018, App. D1). Edwards Aquifer discharge is composed of spring flows and consumptive use through wells. Total annual discharge from six of the most significant springs in the region monitored between 1934 and 2016 varied from 69,800 ac-ft in 1956 to 802,800 ac-ft in 1992, with a median annual discharge of 383,900 ac-ft (Blanton and Associates, 2018, App. D1). Well discharge estimates during the same period ranged from a low of 101,900

___________________

1 An acre-foot (ac-ft) is the amount of water necessary to cover 1 acre of land with 1 foot of water. One acre-foot equals 1,233 cubic meters (m3) of water.

ac-ft in 1934 to a high of 542,400 ac-ft in 1989, with a median annual discharge of 327,800 ac-ft.

ECOLOGY OF THE EDWARDS AQUIFER

The native species of the springs and river systems flowing from the Edwards Aquifer include a variety of submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV), such as Texas wild rice; several fish, including the fountain darter; amphibians, such as the San Marcos salamander; and a variety of invertebrates. All species in the system depend on adequate spring flow, such that reduced flow in Comal and San Marcos springs has periodically resulted in the intermittent loss of habitat and decreased populations. This loss of habitat from reduced flow is the main reason that eight species have been listed for protection under the federal Endangered Species Act (Table 1-1). Other threats to these species include increased competition and predation from invasive species, direct or indirect habitat destruction or modification by humans (e.g., recreational activities), and other factors, such as high nutrient loading and sedimentation that negatively affect water quality and

TABLE 1-1 Common and scientific names of species proposed for coverage under the Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Plan and their status according to the Endangered Species Act

| Common Name | Scientific Name | ESA Status |

|---|---|---|

| Fountain darter | Etheostoma fonticola | Endangered |

| Comal Springs riffle beetle | Heterelmis comalensis | Endangered |

| San Marcos gambusia | Gambusia georgei | Endangered |

| Comal Springs dryopid beetle | Stygoparnus comalensis | Endangered |

| Peck’s Cave amphipod | Stygobromus pecki | Endangered |

| Texas wild rice | Zizania texana | Endangered |

| Texas blind salamander | Eurycea rathbuni | Endangered |

| San Marcos salamander | Eurycea nana | Threatened |

| Edwards Aquifer diving beetle | Haideoporus texanus | Petitioneda |

| Comal Springs salamander | Eurycea sp. | Petitioneda |

| Texas troglobitic water slater | Lirceolus smithii | Petitioneda |

NOTE: Boldface indicates organisms that are the focus of this report, as discussed further in Chapter 2.

aListed as under review by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS).

habitat (FWS, 1996). It should be noted that these species are covered under the ESA primarily because of their limited range and specialized habitat. As a result, the goals for protecting these species are more about sustaining these populations, rather than rebuilding populations that are in decline.

HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN

The ESA, which in this case is enforced by the FWS, protects the listed species from actions that could jeopardize their continued survival. Most relevant to the Edwards Aquifer, the law prohibits the “take” of such species, which the Act defines to mean “harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct.” The law also allows certain entities to apply for and receive an incidental take permit, which defines the number of animals that can be “taken” by certain activities (such as groundwater pumping). For an applicant to receive such a permit, it must develop an HCP.

The HCP for the Edwards Aquifer took years to create and involved many parties (see NRC, 2015, for details). It was finally submitted by the EAA to the FWS in 2012, after which an incidental take permit was issued. The permit lasts 15 years, from March 18, 2013, until March 31, 2028. The five official permittees are the EAA, the City of San Antonio acting through the San Antonio Water System, the City of San Marcos, the City of New Braunfels, and Texas State University. All five have responsibilities under the HCP to implement minimization and mitigation (M&M) measures that will protect the listed species and their habitat. The M&M measures that make up the HCP include four spring flow protection measures as well as other measures designed to maintain and restore the habitat of listed species at both Comal and San Marcos springs. A complete list of the measures can be found in NRC (2015) or the HCP itself (EARIP, 2012). The discussion below focuses on the specific measures that are evaluated in this report for their ability to meet biological goals and objectives for the listed species.

The four spring flow protection measures were designed to provide adequate water during drought and include (1) critical period management, (2) regional water conservation, (3) a voluntary irrigation suspension program, and (4) aquifer storage and recovery. Critical period management refers to reductions in permitted discharges when the spring flow at Comal and San Marcos Springs, or water levels at reference wells J-17 and J-27, fall below certain levels. To offset the risks to listed species under these conditions, the HCP instituted a fifth stage, which would mandate reductions in pumping of 44 percent. The Regional Water Conservation Program builds upon the demand management already being conducted by the City of San Antonio. It is envisioned that new municipal conservation activities can save approximately 10,000 ac-ft/yr (12.33 million m3/yr). The

Voluntary Irrigation Suspension Program Option targets the 30 percent of annual Edwards Aquifer pumping that is withdrawn for irrigation. It relies on permitted irrigators relinquishing their pumping rights when well levels drop below certain triggers; it is intended to conserve another 40,000 ac-ft/yr (49.32 million m3/yr). Finally, the San Antonio Water System runs an aquifer storage and recovery operation in the Carrizo Aquifer that is predicted to make the greatest contribution to overall Edwards Aquifer water savings (as much as 100,000 ac-ft/yr or 123.3 million m3/yr).

Beyond the spring flow protection measures there are a variety of M&M measures designed to maintain and restore the habitat of listed species at both Comal and San Marcos springs. This report evaluates measures to preserve water quality, restore submerged aquatic vegetation, manage recreational activities, and restore riparian areas. This report also considers the refugia created to house populations of the listed species.

THE EAA-REQUESTED STUDY

In late 2013, the EAA requested the involvement of the National Academies to advise on the many different scientific initiatives under way to support the HCP. An expert committee of the National Academies was asked to focus on the adequacy of the scientific information being used to, for example: (1) set biological goals and objectives, (2) determine what M&M measures to use and their effectiveness, and (3) make decisions about the transition from Phase 1 to Phase 2 of the HCP. The study was conducted in three phases from 2014 to 2018 and produced three main reports and one interim report.

Phase 1 of the National Academies study addressed five programs within the HCP: hydrologic modeling, ecological modeling, the biological and water quality monitoring programs, and the Applied Research Program. The resulting report (NRC, 2015) was released in late February 2015. In general, the report was complimentary of the efforts of the EAA and its partners in implementing the HCP and these five programs in particular, while identifying areas that could be improved upon. Many of the report’s recommendations are being implemented, including moving to a single platform for hydrologic modeling, performing uncertainty analysis on the hydrologic model, developing a conceptual model for ecology in both spring systems, devoting new resources to better understanding the CSRB, creating a data management system, and performing statistical analysis of their biomonitoring data.

Phase 2 of the study and the second report (NASEM, 2017) took a much more in-depth look at the ecological model being developed by the EAA and made many recommendations for improving the model. This information was provided to the EAA at an early time point (in the form of

an interim report—NASEM, 2016) to allow its incorporation into model development. The second report also discussed scenarios that could be run in the hydrologic model, particularly the testing of the model against data that were not used in the model calibration—a recommendation that was subsequently followed up on by the EAA. The water quality and biological monitoring programs were again reviewed in the second report, as were the studies that make up the Applied Research Program. Finally, the Committee reviewed implementation of several M&M measures, including the flow protection measures, removal of nonnative SAV and replanting of SAV and Texas wild rice, sediment management, and dissolved oxygen management in Landa Lake. Partly as a result of the Committee’s recommendations, sediment removal in the San Marcos system and dissolved oxygen management in Landa Lake were discontinued.

After the release of each of the two main National Academies reports, the EAA went through a lengthy process to determine how to implement the recommendations of the Committee. Formal response documents, called implementation reports (EAA, 2015, 2017), were created that responded to every recommendation. Although the first implementation report was read and utilized by the Committee during Phase 2 of its study, the second has not been comprehensively reviewed by the Committee because it does not pertain to the tasks of Phase 3.

Phase 3 of the National Academies’ Study

The third and final phase of the National Academies’ study focuses on the biological goals and objectives found in the HCP for each of the listed species (Box 1-1). The first task asks whether the biological objectives, which have flow, water quality, and habitat components, can meet the biological goals, which are often stated as population measures for the listed species. The second task asks whether the M&M measures can meet the biological objectives. For consistency, this report adheres to the terminology used in the HCP of “biological goals” and “biological objectives.” In other circles, biological goals are more commonly referred to as “conservation goals.” The biological goals tend to focus on measures of organism abundance, while the biological objectives deal with the flow, water quality, and habitat conditions necessary to maintain organism abundance.

With respect to evaluating whether the M&M measures can meet the biological objectives, the Committee considered a subset of the 39 M&M measures listed in the HCP, for several reasons. First, many of the M&M measures are not truly conservation measures but are in fact programs (like the monitoring programs) run by the EAA and were already reviewed by the National Academies. Second, some M&M measures listed in the HCP are not directly tied to the achievement of a biological objective, nor were

they highlighted by the EAA as important for consideration in this final report. As a consequence, this report evaluated five major categories of M&M measures, comprising about 75 percent of those listed in the HCP. These categories, shown as gray rows in Table 1-2, are (1) spring flow pro-

TABLE 1-2 Minimization and Mitigation (M&M) Measures Considered in this Report

| M&M Measure | Habitat Conservation Plan Section(s) |

|---|---|

| Spring Flow Protection | |

| Voluntary Irrigation Suspension Program Option | 5.1.2 |

| Regional Water Conservation Program | 5.1.3 |

| Critical period management | 5.1.4 |

| Aquifer storage and recovery | 5.5.1 |

| Water Quality Protection | |

| Decaying vegetation removal program | 5.2.4 |

| Management of floating vegetation mats and litter removal | 5.3.3 and 5.4.3 |

| Low-impact development/best management practices | 5.7.3 |

| Best management practices for stormwater control | 5.7.6 |

| SAV Management | |

| Landa Lake and Comal River aquatic vegetation restoration and maintenance | 5.2.2 |

| Old Channel Environmental Restoration and Protection Area | 5.2.2.1 |

| Texas wild rice enhancement and restoration | 5.3.1, 5.4.1 |

| SAV restoration (nonnative removal and native reestablishment)/maintenance | 5.3.8, 5.4.3, 5.4.12 |

| Recreation Management | |

| Recreation control in key areas | 5.3.2, 5.4.2 |

| Bank stabilization/permanent access points | 5.3.7 |

| Management of public recreational use | 5.3.2.1 |

| Boating in Spring Lake and Sewell Park | 5.3.10 |

| Diving classes in Spring Lake | 5.4.7 |

| Creation of scientific areas | 5.6 |

| Riparian Management | |

| Riparian improvements and sediment removal specific to the Comal Springs riffle beetle | 5.2.8 |

| Bank stabilization/permanent access points | 5.3.7 |

| Restoration of riparian zone with native vegetation | 5.7.1 |

tection, (2) water quality protection, (3) SAV management, (4) recreation management, and (5) riparian management.

The spring flow protection measures that are evaluated include the Voluntary Irrigation Suspension Program Option, the Regional Water Conservation Program, the aquifer storage and recovery program of the San Antonio Water System, and emergency withdrawal reductions during Stage V Critical Period Management. Each of these four measures is intended to contribute, in a cumulative fashion, to maintaining an adequate level of continuous spring flow during a repeat of the Drought of Record conditions

(EARIP, 2012). The water quality protection measures include stormwater best management practices, water quality protection plans, management of golf course diversions, and removal of floating leaf litter. The SAV management measures are designed to restore native vegetation, including Texas wild rice enhancement and restoration in the San Marcos system, nonnative SAV removal in both systems, and SAV restoration and maintenance in both the Comal and San Marcos systems. Recreation management includes the creation of permanent access points, State Scientific Areas, and regulation of boating on and diving in Spring Lake. Finally, riparian management includes replacing invasive riparian plants with native vegetation in both systems.

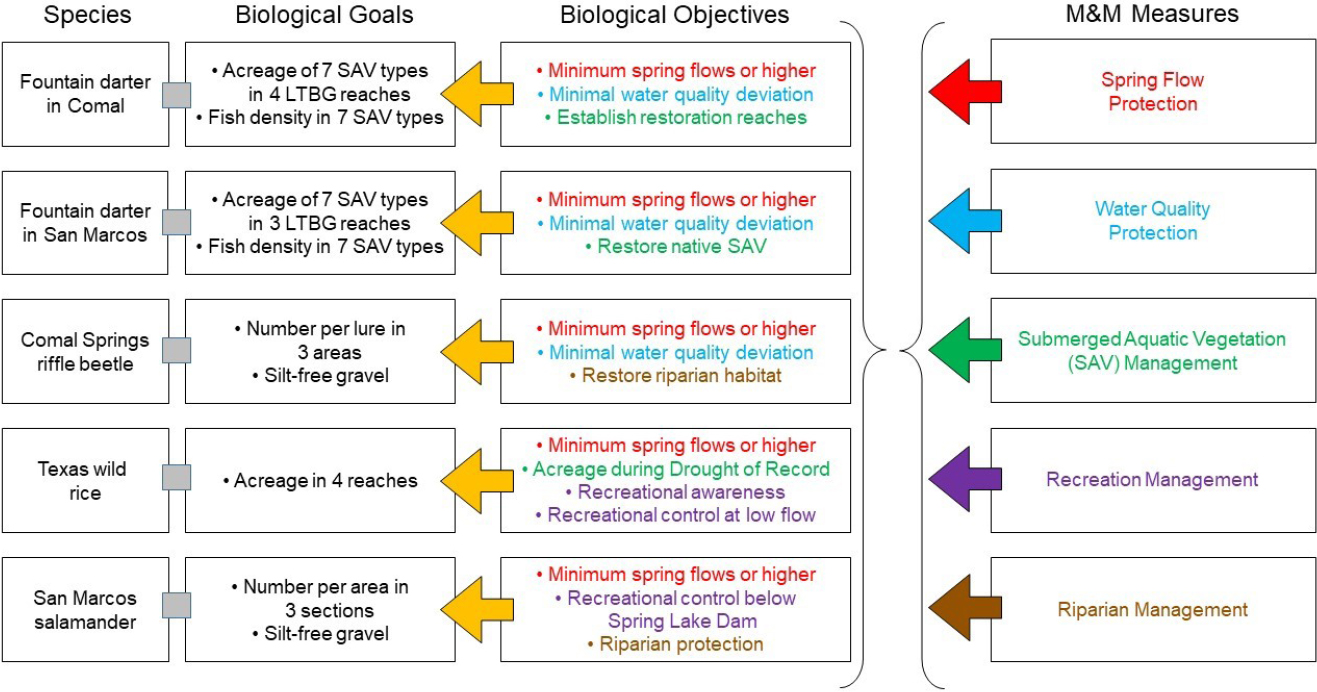

Figure 1-2 shows the biological goals, biological objectives, and M&M measures for four of the listed species considered in this report: fountain darter (shown separately for each system), CSRB, Texas wild rice, and San Marcos salamander. These four species have been identified as sentinel or indicator species that can serve as proxies for the other listed and petitioned species (see Chapter 2).

Figure 1-2 requires explanation in order for the reader to understand the report’s organization. First, the middle columns show the biological goals and objectives for the four species and are paraphrased from the HCP. Details (such as the exact densities of species and the areas in which these numbers must be achieved) can be found in Chapter 2. As mentioned earlier, the column on biological objectives has three components per species: flow, habitat, and water quality, which are indicated with colored text. Red text indicates the flow component, blue text the water quality component, and green text the habitat component of the biological objectives. Note that Texas wild rice and the San Marcos salamander were not assigned a water quality component (and hence have no blue text). Also, some of the habitat components of the biological objectives are worded redundantly with an M&M measure; those that overlap with a recreation management measure appear in purple text while those that overlap with a riparian management measure appear in brown text. The far-right column shows the M&M measures, which are color coded to assist the reader in linking M&M measures to certain components of the biological objectives. Note that Figure 1-2 shows only the five broad categories of M&M measures, not the individual measures listed in Table 1-2.

The gold arrows in Figure 1-2 link biological objectives to the biological goals for each species. (Note that the biological objectives and goals for fountain darters are slightly different for the two systems.) In particular, these arrows indicate that the spring flow, water quality, and habitat components of the biological objective are intended to work in concert to reach a biological goal. The Committee’s first task was to say whether the biological objectives will meet the biological goals (i.e., whether the gold

NOTE: LTBG = long-term biological goal; SAV = submerged aquatic vegetation.

arrows should be labeled as “highly likely,” “likely,” “somewhat likely,” or “unlikely”).

The other colored arrows in Figure 1-2 link M&M measures to certain components of the biological objectives, as indicated by their particular color. For example, the recreation management measures are intended to help achieve the habitat component of the biological objectives for Texas wild rice and the San Marcos salamander. The spring flow protection measures are intended to help achieve the flow component of the biological objectives for all species. The second task of the Committee was to say whether the M&M measures can achieve the biological objectives (i.e., whether the red, blue, green, purple, and brown arrows should be labeled as “highly effective,” “effective,” “somewhat effective,” “ineffective,” or “cannot be determined”).

Chapter 2 discusses the four primary listed species in greater detail, including information about their life history, their biological goals and objectives, and how they are monitored in both systems. Chapter 3 of this report addresses whether the biological objectives can reach the biological goals. This is done for each of the four species shown in Figure 1-2. Chapter 4 considers whether the groups of M&M measures can meet the various biological objectives. Chapter 5 considers several overarching issues, including new analyses for fountain darters and macroinvertebrates and planning for catastrophic events, such as invasive species and floods. Each chapter ends with conclusions and recommendations that synthesize more technical and specific statements found within the body of each chapter. The most important conclusions and recommendations are repeated in the report summary. It should be noted that substantial information provided in the first National Academies report, such as the descriptions of each program, definitions of terms, and rationale for previous recommendations, is not repeated in this report. The reader is referred to NRC (2015) and NASEM (2016, 2017) for such details.

It is also important to recognize what this report does not include. First, in its efforts to evaluate the likelihood of the biological objectives meeting the biological goals, and of the M&M measures meeting the biological objectives, the Committee identified actions that might enhance the likelihood. However, it did not seek to identify responses to the hypothetical situation of the current measures failing to meet either biological objectives or goals. Second, the Committee did not evaluate the influence of external factors, such as population growth and associated increases in water demand on the ability of the M&M measures to meet the objectives. Changes in water demand are handled outside of the HCP by the process through which the EAA distributes permits to water users. Third, this report does not repeat all of the important issues, conclusions, and recommendations from the Committee’s first three reports (NRC, 2015; NASEM, 2016, 2017). For

example, the ecological model is not revisited here, nor is the issue of the representativeness of sampling sites.

The HCP defined biological goals and biological objectives for each of the listed species, and this necessarily placed constraints on the Committee. For example, the biological goals were considered immovable for the purposes of this study, and so Chapter 2 does not critique the specific numeric goals. The flow objectives specify only minimum flow requirements for the listed species because a major goal of the HCP is to protect those species during a recurrence of the Drought of Record. As a result, the report does not consider the full extent of the flow regime on the listed species, although a discussion of extreme flows and their impacts is found in Chapter 5.

Finally, the HCP was written to protect the listed species and their habitat during the 15-year window of the incidental take permit, during which the effects of climate change were not considered (by design). Hence, this report does not consider how climate change may affect the ratings that the Committee assigned to the biological objectives and M&M measures of the HCP. Nonetheless, the Committee recognizes the potentially important role of climate change in the future success of any efforts to protect the listed species, and it explicitly addressed this issue in its first report (NRC, 2015). Climate change is also briefly revisited in Chapter 5.

REFERENCES

Blanton and Associates, Inc. 2018. Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Plan 2017 Annual Report. Prepared for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. March 26. http://www.eahcp.org/files/admin-records/NEPA-and-HCP/EAHCPAnnualReport2017v3_20180313_Redlined_from_Blanton.pdf.

Darby, E. B. 2010. The role of ESA in an atmosphere of climate change regulations. CLE International Conference: Endangered Species Act: Challenges, Tools, and Opportunities for Compliance, June 10-11, 2010, Austin, TX. http://www.eahcp.org/documents/2010_Darby_EndangeredSpeciesAct.pdf.

EAA (Edwards Aquifer Authority). 2015. National Academy of Sciences Review of the Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Plan: Report 1 Implementation Plan. August 20.

EAA. 2017. Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Plan: Report 2 Implementation Plan. July 31. http://www.eahcp.org/files/uploads/Final_Report_2_Implementation_Plan_2017_07_31.pdf.

EARIP (Edwards Aquifer Recovery Implementation Program). 2012. Habitat Conservation Plan. http://www.eahcp.org/files/uploads/Final%20HCP%20November%202012.pdf.

FWS (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). 1996. San Marcos and Comal Springs and Associated Aquatic Ecosystems (Revised) Recovery Plan. Albuquerque, NM: FWS. https://www.cabi.org/isc/FullTextPDF/2011/20117202434.pdf.

Loáiciga, H. A., D. R. Maidment, and J. B. Valdes. 2000. Climate-change impacts in a regional karst aquifer, Texas, USA. Journal of Hydrology 227:173-194.

Mace, R. E., and S. C. Wade. 2008. In hot water? How climate change may (or may not) affect the groundwater resources of Texas. Transactions of the Gulf Coast Association of Geological Societies 58:655-668.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016. Evaluation of the Predictive Ecological Model for the Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Plan: An Interim Report as Part of Phase 2. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2017. Review of the Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Plan: Report 2. Washington DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC (National Research Council). 2015. Review of the Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Plan: Report 1. Washington DC: The National Academies Press.

Scanlon, B., K. Keese, N. Bonal, N. Deeds, V. Kelley, and M. Litvak. 2005. Evapotranspiration Estimates with Emphasis on Groundwater Evapotranspiration in Texas. Prepared for the Texas Water Development Board. December. http://www.twdb.texas.gov/groundwater/docs/BEG_ET.pdf.