4

Strategies for Educational Settings

From preschool through college, the school setting is a universal touch point for children—a place that provides daily opportunities for educators and other professionals to connect with children and families, identify problems, and offer supports. Aside from a child’s home, no other setting has more influence on a child’s mental health and well-being, and it is a critical place to foster healthy mental, emotional, and behavioral (MEB) development.

The relationship between school climate and some MEB outcomes has been well documented, and both researchers and practitioners have explored ways to intervene at the school system level to bring organizational changes that affect whole populations, as opposed to delivering isolated programs aimed at preventing single disorders—a key emphasis of this report. In this chapter, we examine developments in school-based strategies for promoting MEB health and preventing MEB disorders. We focus in turn on early education and preschool settings; grades K–12; and postsecondary settings, for which the evidence is comparatively sparse. We highlight both promotion and prevention programs addressing a range of MEB needs, many of which focus on enhancing social and emotional learning or teaching such contemplative practices as mindful awareness and yoga.1

EARLY EDUCATION AND PRESCHOOL SETTINGS

The value of high-quality early childhood care and education for improving MEB outcomes, especially among children at risk, has been well established, and includes long-term positive impacts on academic learning, socioemotional development, and health (Yoshikawa et al., 2013). Although there is no single definition of what constitutes high-quality early childhood care, the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) has established 10

___________________

1 There are no precise definitions of mindful awareness or mindfulness, but they are commonly understood to have roots in the Buddhist practice of meditation and to encompass activities intended to direct an individual’s attention to the present moment and to cultivate acceptance and curiosity (see, e.g., Bishop et al., 2004).

standards of excellence for early childhood education.2 These standards go beyond basic requirements for creating a safe and healthy learning environment to include factors that promote multiple facets of child development and wellbeing. For example, NAEYC standards require the inclusion of activities that promote positive relationships and encourage individual children’s sense of self-worth; a coherent curriculum that fosters all areas of child development; the inclusion of ongoing progress assessment and home–school communication; instruction in health, nutrition, and injury/illness prevention; access to well-qualified teaching and professional staff; and coordination with community resources.

All children benefit from high-quality preschool, and children from low-income families derive particular benefit (Adams, Zaslow, and Tout, 2007). Yet while research suggests that high-quality universal preschool has the potential to help narrow the academic achievement gap between children living in poverty and ethnic minority children and their more economically advantaged and ethnic majority counterparts, it is the less-advantaged children who are less likely to have access to high-quality preschool (Valentino, 2018).

In the past decade, research has added to the evidence that high-quality early childhood interventions have long-term positive effects on MEB health lasting into adulthood. For example, programs designed to foster social-emotional learning in preschool settings have been found to improve socioemotional development, prosocial behavior, and adjustment to kindergarten (Bierman, Greenberg, and Abenavoli, 2017). This section reviews research on the long-term effects of high-quality preschool and then turns to research on the promotion of social-emotional learning in preschool settings, including a new approach to teaching contemplative practices in early childhood educational settings.

Evidence That Early Education Matters

A number of seminal studies from as early as the 1960s have documented the importance of early childhood education. Preschool programs including the Abecedarian Project, Head Start, the Chicago Child-Parent Center, and the HighScope Perry Preschool Project have now reported longitudinal evidence of benefits that last into adulthood. These examples illustrate the significance of early childhood education for long-term MEB development.

The Abecedarian Project

The Adecedarian Project, developed in the 1970s, was designed to expose children to high-quality care and education from birth until they entered school. It has served primarily African American children in low-income settings in rural

___________________

2 See https://www.naeyc.org/our-work/families/10-naeyc-program-standards.

North Carolina.3 Participants received intensive pediatric monitoring, improved nutrition, and a more predictable and less stressful child care experience, which resulted in improved adult outcomes (Campbell et al., 2014). Longitudinal studies of participants have shown positive outcomes that last at least into young adulthood. For example, participants studied as adults were found to have had more years of education, to have been more consistently employed, and to have been less likely to receive public assistance. While there were no differences in rates of criminal conviction, participants were significantly more likely to have delayed parenthood (Campbell et al., 2012). Most striking was the impact of the program on participants’ health in their mid-30s. As adults, the participants showed significantly lower rates of prehypertension and hypertension and a lower risk for coronary heart disease, and none exhibited symptoms of metabolic syndrome.

Head Start

The federally sponsored Head Start program focuses on improving the school readiness of children from low-income families by providing comprehensive enriched classroom experiences, nutrition, and family supports from birth until age 5.4 Strong evidence indicates that this program improves long-term outcomes. Analysis of data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study–Birth Cohort, a nationally representative sample of children born in 2001 (Schanzenbach and Bauer, 2016), showed that Head Start participants were more likely to graduate from high school; attend college; and earn a degree, license, or certificate. Other benefits to participants include improved self-control and self-esteem and the use of positive parenting practices when they become parents themselves.

However, recent evaluations of statewide preschool programs have raised questions about the extent of universal public health benefits when these otherwise high-quality programs are implemented at scale. For example, Lipsey and colleagues (2018) examined long-term outcomes for a subsample of children randomly assigned to attend the state-mandated Tennessee Preschool Program and followed this sample through 3rd grade. By the end of pre-K, program participants did indeed show better outcomes on measures of academic achievement and school readiness, compared with children who did not attend the state-mandated program. However, those effects were not sustained into subsequent years, and by the end of 3rd grade, the pre-K program participants actually scored lower on achievement measures and had more disciplinary infractions compared with nonparticipants. The authors of this study identified questions about the design and implementation of the state pre-K program and

___________________

3 For more information, see https://abc.fpg.unc.edu/design-and-innovativecurriculum.

4 For more information, see https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ohs/about.

called for additional research on the implementation quality and heterogeneity of effects.

Early Head Start is a federally funded community-based program created in 1995 for low-income families with infants and toddlers and for low-income pregnant women. The goal of Early Head Start is to provide prenatal support to pregnant women, support healthy family functioning, and support the development of children from birth to age 3. Studies of the program have documented significant benefits for program participants, including improved parenting skills, vocabulary, and cognitive functioning, and superior social-emotional functioning among students and families who participated in the program (Administration for Children and Families, 2002, n.d.).5

The Child-Parent Center

The Child-Parent Center Education Program is a publicly funded intervention that begins in preschool and provides up to 6 years of support to children and families in inner-city Chicago schools.6 A study examined the long-term impacts of this program on indicators of well-being up to 25 years later among more than 1,400 participants (Reynolds et al., 2011). As adults, participants demonstrated higher educational attainment, income, socioeconomic status, and rates of health insurance coverage relative to the comparison group, as well as lower rates of involvement in the justice system and less substance abuse. Impacts were strongest for males and children of parents who had dropped out of high school.

The HighScope Perry Preschool Project

Beginning in 1962, researchers began following a cohort of 123 African American preschool-age children with risk factors for school failure; data collection continued until they reached age 50. These children were randomly assigned to participate in a high-quality preschool program or to receive no preschool.7 The preschool program used the play-based HighScope curriculum and also included home visiting and parenting support. Multiple studies have confirmed the preschool program’s effectiveness (Schweinhart, 2013). Compared with nonparticipants, those assigned to receive preschool performed better in school, showed less antisocial behavior, were more likely to graduate from high school, were more likely to be employed, earned more, and were more likely to

___________________

5 A three-phase evaluation study was carried out between 1996 and 2010. See https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/research/project/early-head-start-research-and-evaluationproject-ehsre-1996-2010. See also DiLauro (2009), Raikes et al. (2003), and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2002, 2003, 2006, 2010).

6 For more information, see https://cps.edu/Schools/EarlyChildhood/Pages/Childparentcenter.aspx.

7 For more information, see https://highscope.org/perry-preschool-project.

own their own homes. Participants were also significantly less likely to engage in criminal behavior by age 40. An updated cost/benefit analysis found that the program’s return on investment was seven times the costs involved in operating the program (Schweinhart, 2013). Most recently, follow-up research has documented benefits for the siblings of the original participants and also for the children of the children who originally participated, including higher levels of educational attainment and employment, fewer school suspensions, and lower levels of participation in crime (Heckman and Karapakula, 2019a, 2019b).

Challenges

The studies cited above demonstrate the long-lasting influence that early childhood intervention can have well into adulthood. What has also been evident over the past 50 years, however, is that high-quality, multicomponent early education programs such as these can also be challenging to scale up. At present, access to high-quality early childhood education is very uneven across and within states, and also varies significantly by income level and race; according to the U.S. Department of Education, “more than 2.5 million four-year-olds don’t have access to publicly funded preschool programs” (U.S. Department of Education, 2015, p. 4). Factors in the ongoing challenge of ensuring that all children have access to high-quality programs include the cost of providing high-quality care, limitations in the preparation of many members of the early childhood education and care workforce, and low compensation levels for this workforce, especially in underresourced communities. These barriers will need to be addressed if preschool is to contribute to the healthy MEB development of children at a population level.

Social-Emotional Learning in Early Childhood Education

The past 15 years have seen a trend toward introducing academics in kindergarten, which in turn has increased concern that preschools need to better prepare children academically (Bassok, Latham, and Rorem, 2016). But this trend has also prompted warnings that young children are being asked to engage with content for which they are not yet developmentally ready, resulting in such negative outcomes as increased stress, reduced motivation and efficacy, and increases in negative attitudes toward school (Carlsson-Paige, McLaughlin, and Almon, 2015; Stipek, 2006). Another concern is that this focus on academics is crowding out time for social-emotional learning and undermining the development of skills shown to promote school success and feelings of connection with school (Bierman, Greenberg, and Abenavoli, 2017). These skills are critical. For example, one recent study suggests that kindergarten children’s ability to get along with others, follow rules and procedures, and persist with tasks that are challenging predicts later success in both school and life (Jones, Greenberg, and

Crowley, 2015). Indeed, children without such skills may have difficulty adjusting to school and learning (Durlak et al., 2011).

Preschool is an optimal time to introduce social-emotional learning programs because socioemotional development, including associated brain development, is rapid during these years and benefits from high-quality interactions with adult caregivers (Blair and Raver, 2015). Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that evidence-based programs can promote these skills during the preschool years (Bierman and Motamedi, 2015; McClelland et al., 2017; Schindler et al., 2015). Comprehensive social-emotional learning programs in preschool focus on both interpersonal skills (making friends, getting along with others, taking turns, sharing, controlling aggressive behavior) and intrapersonal skills, such as emotion regulation and cognitive control (paying attention, inhibitory control, following directions). Such programs also provide support for teachers—both professional development and support in building teachers’ own social-emotional learning skills (Bierman, Greenberg, and Abenavoli, 2017; McClelland et al., 2017).

This body of work has shown that at the preschool level, the most effective interventions apply direct instruction and practice in daily activities and interactions, enabling children to practice and generalize social-emotional learning skills across various contexts and situations. In the most effective programs, more complex and challenging activities are introduced as children mature and grow, and children’s families are involved so the skills learned generalize to the home context. Strategies to educate parents in ways to support children’s social-emotional learning have also shown promise (McClelland et al., 2017).8

Some programs designed to support socioemotional development among preschoolers involve contemplative or mindful awareness activities. While more research is needed to improve understanding of the potential benefits of such programs, two examples illustrate their potential. The Kindness Curriculum introduces children to simple, developmentally appropriate mindful awareness practices designed to promote attentional skills, kindness, compassion, and gratitude. One study found that the program had significant impacts on children’s teacher-rated social competence, prosocial behavior, and grades, but no effect on executive function (cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, or capacity for delayed gratification) (Flook et al., 2015). Another example is MindUp, a social-emotional learning program that integrates mindful awareness practices with practices from positive psychology (see Box 4-1). Two quasi-experimental studies of the preschool version of MindUp showed significant impact on teacher-reported executive functioning, literacy, and vocabulary skills, but no impact on receptive vocabulary, observed classroom interactions, social skills, or academic skills (Thierry et al., 2016, 2018). And a rigorous RCT examining the impact of

___________________

8 Practitioners and policy makers can find information about evidence-based social-emotional learning programs at https://healthdata.gov/dataset/evidence-based-practices-resource-center; https://casel.org/guide; and https://www.blueprintsprograms.org.

MindUp found effects for executive function, empathy, perspective taking, emotional control, optimism, school self-concept, math achievement, mindfulness, peer-rated prosocial behavior, and peer acceptance. The researchers also found reduced depression and aggression in students who participated in the program (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015).

K–12 SETTINGS

Interventions designed for the K–12 level include promotive programs, such as those intended to develop positive school climates or teach social and emotional skills, and programs targeted at specific problems, such as bullying and suicide, and populations of students at particular risk.

Promotion of MEB Health

School-wide programs that promote MEB health at the K–12 level are most commonly designed to improve the ways school staff respond to problem behaviors and to support the social-emotional learning of students.

Promoting a Positive School Climate

A positive school climate can significantly influence learning and positive youth development, as we discussed in Chapter 2. There is evidence that school climate can influence students’ sense of social connectedness and foster greater school engagement, academic achievement, and prosocial behavior, and some states have begun to assess school climate and include it in their accountability systems (Kostyo, Cardichon, and Darling-Hammond, 2018). The Department of Justice recently issued a report on the importance of creating and sustaining a positive school climate, to promote school safety and yield benefits for students that include better socioemotional health (Payne, 2018). The report notes that

while research has identified ways to improve school climate, there is a gap between the research and existing policy, and that many states, districts, and schools are using tools to promote positive school climates that are not grounded in the evidence that has been amassed. The report points out the lack of a shared definition of school climate and the need for further research on ways to assess it. A key message of the report, based in the research reviewed, is that the entire school community must be involved in an effective effort to build a strong climate, a view that is extensively documented in another recent report that summarizes a broad base of literature on the subject (Darling-Hammond and Cook-Harvey, 2018).

One example of a universal intervention that promotes a positive school climate is School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, which focuses on changing the behavior of school staff and improving the conduct of such administrative tasks as discipline, data management, and office referrals. An RCT showed that social-emotional learning, prosocial behaviors, concentration, and externalizing behaviors all significantly improved in the participating schools (Bradshaw, Mitchell, and Leaf, 2010; Bradshaw, Waasdorp, and Leaf, 2012). Teacher-reported student bullying and peer rejection were also reduced (Waasdorp, Bradshaw, and Leaf, 2012).

Chapter 2 also notes that preventing adverse childhood experiences and peer rejection may have significant positive effects on MEB development, and schools nationwide have begun to support staff education about the effects of trauma on children (Chafouleas et al., 2016). However, despite interest in “trauma-informed schools,” there are few evaluations that document how whole-school strategies to improve school climate affect trauma-related mental health and well-being in children.

Promoting Social-Emotional Learning

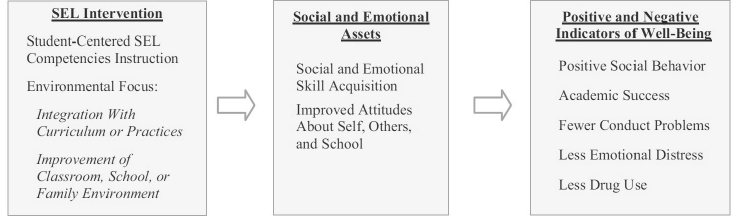

Increasingly, states are using the teaching of social-emotional learning skills to improve school climate and student engagement, and thereby promote healthy MEB development in schools: All 50 states now include social-emotional learning in their educational standards for preschool, and a growing number have adopted these standards for grades K–12 (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, 2018). (See the introduction to Part I of this report for discussion of competence domains defined for social-emotional learning.) Many programs to promote these skills focus on integrating them into the overall curriculum in schools and engaging teachers and other school staff in teaching students how to better manage emotions, set positive goals, express empathy, and establish positive peer relationships (Durlak et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2017). Figure 4-1 illustrates the theory of change for social-emotional learning interventions: such interventions foster assets in young people, which in turn promote positive behavioral, academic, and mental health outcomes.

NOTE: In this framework for positive youth development, interventions designed to promote social and emotional learning foster assets (skills and attitudes) that bring positive outcomes.

SOURCE: Taylor et al. (2017).

Several recent reviews have confirmed the short- and long-term benefits of universal school-based health promotion interventions that teach one or more social-emotional learning skills; these include positive and lasting effects across a range of key developmental outcomes, both promoting wellness and preventing illness. A meta-analysis of universal social-emotional learning interventions found positive effects, including improvements in social skills, mental health, prosocial behaviors, academic achievement, and prevention of antisocial behavior and substance abuse (Sklad et al., 2012). Another meta-analysis of school-based social-emotional learning interventions showed that program effects were significant for outcomes ranging from general social-emotional learning skills (social-cognitive and affective competencies) to positive social behavior, prevention of conduct problems and emotional distress, and gains in academic achievement (Durlak et al., 2011).

A third meta-analysis examined follow-up effects (outcomes 6 months or more postintervention) for 82 studies of school interventions focused on social-emotional learning published from 1981 to 2014, involving more than 97,000 K–12 students (Taylor et al., 2017). This meta-analysis not only found that social and emotional functioning improved with social-emotional learning interventions, but also documented modest improvements in academic performance as assessed by grades and test scores from school records, changes that exceeded those found with many educational programs (Hill et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2017). Findings from Taylor and colleagues (2017) further demonstrate that these results are similar regardless of students’ race, socioeconomic background, or school location. Moreover, cost/benefit analyses of these programs have shown that every $1 spent yields an $11 return (Belfield et al., 2015) (such analyses are discussed in Chapter 9).

Other researchers have focused on programs that build resilience, defined as the “maintenance of, or return to, positive mental health following adversity by using a collection of multiple internal (personal characteristics or strengths) and external (qualities of wider family, social, and community environments)

resilience protective factors (assets and resources) that enable an individual to thrive and to overcome disadvantage or adversity” (Dray et al., 2017, pp. 813–814). A meta-analysis of universal prevention programs in schools showed effectiveness for programs focused on strengthening at least three internal resilience protective factors for preventing mental health problems (Dray et al., 2017). The majority of trials included in this review used cognitive-behavioral therapy approaches, but other trials implemented positive psychology, social-emotional learning, teaching of social skills and mindfulness, and other strategies. Across all trials, these interventions had a positive effect on behavioral outcomes. Child but not adolescent interventions had a significant effect on anxiety symptoms; no differences were found for conduct and hyperactivity symptoms. Box 4-2 describes an example of a social-emotional learning curriculum.

Although high-quality professional development is critical to the effectiveness of social-emotional learning programs, teacher preparation typically does not include instruction in social-emotional skill development and the knowledge and skills required to deliver such instruction effectively, Jennings and Frank, 2015). Consequently, few teachers are prepared to deliver social-emotional learning programs and generalize those skills in their classroom management strategies and interactions with students, or to integrate social-emotional learning concepts into other curricular content. Furthermore, the quality and duration of training teachers receive in delivering social-emotional learning programs vary widely (Jennings and Frank, 2015).

Promoting Contemplative Practices

Since 2000, considerable attention has been focused on evaluating the impacts of interventions based on contemplative practices or mindful awareness. Promising results for adult populations have generated interest in applying such practices to fostering healthy MEB development among children and youth in school settings.9 While mindfulness is typically associated with meditation, it can be cultivated through a variety of other practices included under the rubric of mindful awareness, such as yoga, tai chi, and qigong, and can be practiced both formally and informally, such as while engaging in routine daily activities (e.g., eating, listening, or walking) (Williams and Kabat-Zinn, 2011).

Mindfulness approaches designed to be delivered in school settings for both students and teachers are becoming more common, and a growing body of research is showing that these interventions hold promise (Felver and Jennings, 2015). More research is needed, however, on which practices are most effective at developing mindfulness, for whom and at what ages, the optimal dosages and frequencies of program exposure for different types of mindfulness practices, and how best to integrate mindfulness approaches into school settings. As with training for teachers in the delivery of social-emotional learning programs, mindfulness programs have varied in duration and intensity, from daily activities offered across the school year to limited-duration programs lasting for several weeks to several months. Conclusions from research on these programs to date have been limited by small samples, few rigorous RCTs, a lack of longitudinal data, measurement limitations, and a lack of fidelity monitoring.

Although several models of the key components of mindfulness approaches have been proposed to explain their effects, their specific mechanisms are not fully understood (Grabovac, Lau, and Willett, 2011; Howell and Buro, 2010; Jankowski and Holas, 2014; Shapiro et al., 2006; Zelazo and Lyons, 2012). One hypothesis is that mindfulness practices help individuals cultivate distress tolerance, or the general capacity to persist in goal-directed behavior despite experiencing strong emotions (Broderick and Frank, 2014; Daughters et al., 2008). Through engagement in mindfulness practices, students learn to be more attentive to present-moment experiences and more aware of emotions that arise. This metacognitive awareness is a first step toward the cultivation of strategies for managing strong emotions through nonjudgmental awareness, openness, and acceptance. These skills in turn serve as key emotion regulation strategies that can be used to moderate affective experiences to meet the demands of different situations and achieve personal and learning goals during times of heightened stress (Campos, Frankel, and Camras, 2004; Eisenberg and Spinrad, 2004; Op’t Eynde and Turner, 2006). The increased levels of awareness and control over emotional responsiveness attained through mindfulness practices may decrease

___________________

9 Mindfulness-based interventions were popularized as an approach to stress reduction through the work of Jon Kabat-Zinn (1982).

negative affect and reduce rumination and somatic symptoms that have been implicated in the development of anxiety, depression, drug use, and poor school performance (Broderick and Jennings, 2012; refer to Figure 4-1).

Mindfulness practices also strengthen emotion regulation because they shift the individual’s focus away from the past (e.g., memory of a troubling incident) and the future (e.g., apprehension of impending trouble) and disrupt patterns of automatic responding. Together, these benefits may help protect children and adolescents against the potential risks of developing internalizing and externalizing problems linked to deficits in emotion regulation and reduce overall reactivity to stress known to impair executive functions, including attentional control, working memory, and problem-solving capacity (Blair, 2002; Liston, McEwen, and Casey, 2009). In addition, voluntarily and repeatedly orienting attention to a specific object of focus (e.g., breath) while deliberately letting go of distractions may strengthen key executive functions involved in the regulation of attention.

A few individual studies illustrate how some mindfulness approaches are designed and their results. For example, study of the weekly .b or “dot-be” Mindfulness in Schools Project (2013), a training program for students, has shown null and/or iatrogenic effects for depression and eating disorders and increased anxiety in a sample of young adolescents, although the authors cite the quality of program delivery as problematic (Johnson et al., 2016, 2017). Another approach is that of the MindUp program, discussed earlier (refer to Box 4-1). Another program for which there is some evidence of effectiveness is MindfulKids, a universal primary school-based prevention strategy (van de Weijer-Bergsma et al., 2012). Fewer studies have been conducted on yoga interventions for youth, but researchers have begun to explore it. Most youth yoga interventions have been delivered in school contexts, and there is evidence of such benefits as improvements in stress management and reductions in self-reported anxiety and other psychological distress symptoms (Cramer et al., 2015; Daly et al., 2015; Fishbein et al., 2016; Frank, Bose, and Schrobenhauser-Clonan, 2014; Hagins, Haden, and Daly, 2013; Khalsa et al., 2012; Mendelson et al., 2010; Noggle et al., 2012). As with other research on mindfulness approaches, however, the emerging research on yoga for youth has a number of methodological limitations. Because the outcome domains and measures are heterogeneous, it is difficult to draw conclusions about program effects on any given outcome. More than half of studies have included an active control condition, but some control groups have consisted of existing school programming (e.g., gym class), so the researchers could not control for such intervention elements as novel programming and exposure to unfamiliar instructors. Many studies also suffer from biases, including failure to blind participants or to report on participant attrition.

Several narrative and systematic reviews and meta-analyses have examined the effects of mindfulness and more general contemplative practices (including yoga) in school-age youth. Narrative reviews, including those by Meiklejohn and colleagues (2012), Greenberg and Harris (2012), and Thompson and Gauntlett-Gilbert (2008), indicate that mindfulness-based approaches are feasible and

promising, but the authors cautioned that further, more rigorous research is needed. Two meta-analyses of mindfulness-based interventions involving children and adolescents found positive and significant effects on multiple psychological outcomes. Zoogman and colleagues (2014) report on a synthesis of 20 studies published between 2004 and 2011 examining the efficacy of mindfulness meditation with clinical and nonclinical youth samples (e.g., psychiatric outpatients) across several dimensions of psychological functioning and well-being. Subsequent meta-analyses conducted by Zenner and colleagues (2014) of mindfulness approaches delivered in school settings also found evidence of effects on youths’ cognitive performance, resilience, and stress measures. A recent random-effects meta-analysis examined studies of mindfulness-based interventions for children and adolescents up to October 2017 and showed significant positive impacts for mindfulness approaches in strengthening executive functioning and attention and reducing depression, anxiety, stress, and negative behaviors (Dunning et al., 2019).

Many mindfulness approaches that have been tested for children and adolescents were adapted from existing adult programs. With few exceptions (e.g., Tan and Martin, 2013), limited detail has been provided in publications regarding the rationale for modifications, and the optimal duration and frequency of practices across populations of developmentally heterogeneous youth are currently unknown. However, it is important to note that many of the components common in youth mindfulness programs (e.g., diaphragmatic breathing, body scan) have been used within the context of other, non-mindfulness-based programs safely for many years (Benson et al., 1994; Wyman et al., 2010).

Furthermore, programs vary with regard to the degree of home practice involved and its nature. Children and adolescents are likely to be more engaged in mindful awareness practices embedded into daily routines, such as mindful eating, listening, and body scan prior to sleep, as these daily routines can serve as a cue to practice. Finally, even older adolescents have less well-developed verbal and abstract reasoning skills than adults. Traditional sitting mindfulness meditation practice is generally modified to accommodate these differences (e.g., by shortening the practice or simplifying the instructions), but the modifications necessary to make the content understandable and engaging for diverse groups of students are not well understood. Additional research on these interventions, including analysis of hypothesized core program components (see Chapter 7) and implementation fidelity, will be valuable (Gould et al., 2016).

Health Promotion for the Education Workforce

Teaching at all levels (pre-K–12) is stressful and emotionally demanding (see Chapter 2), but research, policy, and practice are only beginning to focus attention on the development of teachers’ social-emotional competence, their well-being, and the working conditions that support their job satisfaction and emotional and physical health (Greenberg, Brown, and Abenavoli, 2016; Papay

and Kraft, 2013). Causes of stress for teachers include characteristics of the school (such as leadership, salaries, resources, and collegial relationships); job demands (such as high-stakes testing and behavioral issues among students); and teachers’ perceptions of their autonomy and capacity to manage stress (Greenberg, Brown, and Abenavoli, 2016). When schools provide the support teachers need and teachers develop the social-emotional competencies required to manage the demands of teaching, they can better regulate their emotions and behavior and are more able to provide emotional support to their students; these capacities are linked to desired student outcomes (e.g., academic achievement, prosocial behaviors, and students’ own social-emotional competencies) (Fried, 2011; Jennings and Greenberg, 2009).

Research in this area is limited, but several programs and policies have been found to reduce teachers’ stress, promote their well-being, and improve classroom and student outcomes. Mentoring and induction programs for beginning teachers improve teachers’ satisfaction and retention and improve students’ academic achievement (Ingersoll and Strong, 2011). Workplace wellness programs reduce health risk, health care costs, and absenteeism (Aldana et al., 2005; Merrill and LeCheminant, 2016; Merrill and Sloan, 2014). Programs designed to promote students’ social-emotional learning and improve their behavior have been found to create more positive teacher engagement with students and to reduce teacher stress (Abry et al., 2013; Domitrovich et al., 2016; Tyson, Roberts, and Kane, 2012; Zhai, Raver, and Li-Grining, 2011). Finally, mindfulness-based stress reduction programs reduce teachers’ stress and improve their coping skills, and also improve classroom interactions and student outcomes (Brown et al., 2017; Jennings et al., 2017; Jennings, Minnici, and Yoder, 2019; Roeser et al., 2013).

Prevention Strategies

Some school-based interventions foster healthy MEB development by focusing on the prevention of specific behavioral health conditions that affect individuals—such as disruptive behavior disorders, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, depression, and substance use disorders—as well as problems that affect the broader school community and result from multiple individual, social, and system conditions, such as bullying, violence, and suicide. While some school-based prevention programs have focused mainly on one disorder, researchers increasingly have been examining multiple outcomes and developing programs aimed at both promoting healthy development and preventing MEB disorders.

Disruptive Behavior

School-based interventions to prevent disruptive behavior include universal, selective, and indicated approaches and are frequently delivered during the elementary school years. Universal approaches (e.g., the Good Behavior Game, described in Box 4-3) are often integrated into general school practices.

Interventions classified as social-emotional learning programs, discussed above in the context of MEB health promotion, also often have a goal of reducing disruptive behavior. For instance, multiple studies have shown that the Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies Program not only improves social and emotional outcomes for children but also reduces aggressive and disruptive behavior (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009). Other programs for which there is evidence of effectiveness include

- The Incredible Years Training Series, programs designed to reduce disruptive behavior and improve social-emotional learning and self-regulation in children ages 0–12 (Baker-Henningham et al., 2012; Hutchings et al., 2013; Kirkhaug et al., 2016; McGilloway et al., 2010);

- INSIGHTS into Children’s Temperament, an intervention that teaches students, teachers, and parents about temperament differences and how best to support healthy development for children of different temperaments (O’Connor et al., 2014);

- Anger Coping/Coping Power, a cognitive-behavioral intervention with school and parent components, targeted at reducing aggressive or disruptive behavior (Lochman et al., 2013);

- First Step to Success, a 3-month school- and parent-focused intervention for students in grades 1–3 with externalizing problems (Sumi et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2009); and

- Fast Track, an intensive school-based intervention targeting kindergarten children identified as at risk for behavior problems (Albert et al., 2015).

Anxiety Disorders

School-based programming focused on anxiety prevention has often been delivered in the elementary grades because anxiety disorders begin to emerge in childhood, with the onset of specific phobias and separation anxiety disorder being more common in children and the onset of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder being more common in late childhood and adolescence (Burstein et al., 2012). Anxiety prevention programs are most commonly delivered in a group format with a focus on cognitive-behavioral strategies; both universal and selective approaches have been used.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of these programs have generally reported small but significant effects in reducing anxiety symptoms immediately following programming (Ahlen, Lenhard, and Ghaderi, 2015; Corrieri et al., 2014; Fisak, Richard, and Mann, 2011; Neil and Christensen, 2009; Werner-Seidler et al., 2017). Some reviews have found that indicated approaches had more robust effects than universal approaches did (Stice et al., 2009; Teubert and Pinquart, 2011), whereas others have found no differences related to prevention level (Werner-Seidler et al., 2017). Intervention benefits also have not been found to differ as a function of program delivery by school personnel versus external facilitators (mental health professionals or research staff) (Ahlen, Lenhard, and Ghaderi, 2015; Werner-Seidler et al., 2017), a promising finding with respect to the potential for sustainability and scale-up. Other reviews have found that delivery by an external facilitator was more effective (Fisak, Richard, and Mann, 2011; Stice et al., 2009; Teubert and Pinquart, 2011), but these findings may have been influenced in part by the fact that indicated programs were more likely to use mental health professionals as facilitators given the higher symptom levels of participants (Ahlen, Lenhard, and Ghaderi, 2015; Stice et al., 2009).

Cognitive-behavioral approaches are the most commonly used interventions in school-based anxiety prevention programs. Some studies, however, have evaluated the potential of other approaches, such as interpersonal and mindfulness programs.10

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Trauma

The effects of traumatic events and adverse experiences on the development of children and youth can be profound (see Chapter 2). In addition to the effects on a student’s biological and MEB development, these adverse experiences have been shown to be related to negative changes in academic performance, school attendance, disciplinary referrals, and graduation rates, which are outcomes of high priority for educators (Kataoka et al., 2012; Strøm et al., 2016). Prevention

___________________

10 Examples include the FRIENDS Program (Barrett, 2010), the Coping Cat/C.A.T. Program, Cool Kids/Cool Kids Chilled, and Social Effectiveness Training for Children (SET-C).

programs have been developed to support students who have undergone these experiences (Santiago, Raviv, and Jaycox, 2018).

A systematic review of school-based interventions for symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder found 16 studies that used cognitive-behavioral therapy, 11 of which had effect sizes in the medium to large range (Rolfsnes and Idsoe, 2011). Other approaches studied included Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, play and art therapy, and Mind-Body Skills, all of which showed promising results. This review found as well that school professionals could deliver these trauma interventions feasibly and effectively.11

The importance of schools in providing access to prevention services is supported by evidence from Jaycox and colleagues (2010). They compared two effective trauma interventions—one delivered in schools and the other in a clinical setting—and found that 91 percent of those randomly assigned to receive services in a school completed the intervention, compared with only 15 percent of those assigned to receive care in a clinic.

More recent studies have examined classroom interventions for traumatized youth in urban schools in the United States and youth experiencing war and political violence outside the United States. The Mindfulness Stress Reduction Program, a 12-week curriculum originally created for adults and adapted for students in grades 5–8, teaches mindfulness, meditation yoga, and mind–body connection (Sibinga et al., 2016). In an RCT, the students who completed this program showed greater improvements in posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms relative to those randomized to a health education program.

Similarly, an evaluation of a universal classroom curriculum for youth exposed to war trauma, consisting of psychoeducation, skills training, and resiliency strategies for traumatic stress combined with strategies to reduce stereotyping and discrimination, found improvement in posttraumatic stress, depression, anxiety, and somatization, as well as a relationship between reduction in posttraumatic stress and decreased prejudicial attitudes toward minorities (Berger, Gelkopf, and Heineberg, 2012). A follow-up study showed positive effects for the teachers, decreasing their primary and secondary traumatic stress symptoms, in addition to improving their self-efficacy in helping other trauma survivors, their sense of hope for the future, and their use of positive coping strategies (Berger, Abu-Raiya, and Benatov, 2016). Another teacher-led classroom prevention program for adolescents exposed to war trauma taught teachers and school counselors strategies for enhancing students’ self-efficacy and social support in a crisis following war. In an RCT, researchers found improvements in emotional symptoms and psychological distress, as well as mobilization of social support and self-efficacy, for those receiving the program compared with a control group (Slone, Shoshani, and Lobel, 2013).

Despite the strong and growing evidence of the negative effects of trauma and adverse experiences on the MEB development of children, few school-based

___________________

11 See also Chemtob, Nakashima, and Carlson (2002); Layne et al. (2008); and Stein et al. (2003).

trauma interventions have as yet been extensively evaluated using rigorous designs. Schools may be the ideal setting in which to deliver early interventions to prevent traumatic stress in youth, including promising strategies for whole classrooms that are delivered by teachers, as well as selective and indicated interventions that also can be delivered in schools. Studies of the feasibility and sustainability of trauma interventions in schools yielding evidence for better MEB outcomes, along with dissemination studies with diverse populations, would provide important information about opportunities for improvement at a population level.

Depressive Disorders

Prevention of depression is a key focus for school-based prevention programming. Given that the risk for depression begins to increase during adolescence, most school-based depression prevention programs are delivered in middle school in a group format and based on cognitive-behavioral therapy principles (e.g., Gillham et al., 2012; Rohde et al., 2015). Some programs have also been tested with high school students (e.g., Melnyk et al., 2013, 2015). Both universal and targeted approaches have been used. Several reviews over the past 10 years have evaluated trials of depression prevention programs delivered in schools (Calear and Christensen, 2010; Corrieri et al., 2014; Werner-Seidler et al., 2017). Other recent reviews have included depression prevention trials for children and adolescents more generally, with most but not all being conducted in schools (Ahlen, Lenhard, and Ghaderi, 2015; Das et al., 2016; Hetrick et al., 2015; van Zoonen et al., 2014).

Studies assessing factors that may moderate the impact of school-based depression prevention have yielded mixed results. As with interventions focused on prevention of anxiety, for example, some reviews have found that program effects do not differ significantly regardless of whether programs are delivered by external facilitators, such as mental health professionals, research staff members, or school personnel such as classroom teachers (Ahlen, Lenhard, and Ghaderi, 2015), whereas others have found better outcomes with external facilitators (Calear and Christensen, 2010; Werner-Seidler et al., 2017). Some reviews have found larger effect sizes for indicated versus universal programs (Calear and Christensen, 2010). There is also some heterogeneity in the intervention outcomes assessed; most studies have assessed depressive symptoms as the outcome, but some studies have generated evidence for significant prevention effects on depression incidence (Merry et al., 2011).

Prevention programs generally have shown small but statistically significant effects in reducing depressive symptoms in children and adolescents (Ahlen, Lenhard, and Ghaderi, 2015; Calear and Christensen, 2010; Corrieri et al., 2014; Merry et al., 2011; Stice et al., 2009; Teubert and Pinquart, 2011; Werner-Seidler et al., 2017). There is consistent evidence that small but significant benefits of depression prevention interventions were sustained over follow-up periods of less

than 1 year, but several reviews found that benefits generally were not maintained over longer periods (Ahlen, Lenhard, and Ghaderi, 2015; Kavanagh et al., 2009; Merry et al., 2011; Stice et al., 2009; Werner-Seidler et al., 2017). A recent integrative data analysis of 19 adolescent depression trials testing nine interventions through 2-year follow-up, however, found a significant overall effect on reduction of depressive symptoms at 2 years (Brown et al., 2018). This study indicated stronger effects for interventions that specifically targeted depression, rather than problem behaviors or general mental health, and for youth with elevated depressive symptoms.

Substance Use Disorders

School-based interventions to prevent substance use are generally delivered in middle or high school, the ages when many young people begin to experiment with smoking, alcohol, and illicit drugs. Most substance use prevention programs have targeted tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, or illicit drugs specifically, although some have targeted substance use more generally.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of school-based programs targeting tobacco use have reported mixed findings. A meta-analysis of 16 trials of smoking prevention programs for girls did not find overall evidence for efficacy (de Kleijn et al., 2015). Another meta-analysis of smoking prevention programs found no effect for the pooled trials at 1-year follow-up or prior but did find a modest reduction in smoking initiation (Thomas, McLellan, and Perera, 2015). This review also found that intervention curricula based on teaching skills derived from theories of social competence and social influences produced significant gains at both follow-ups. Consistent with that finding, Flay and colleagues had earlier observed that school-based smoking prevention programs based on these theories were more likely to be effective than other approaches and that intervention characteristics associated with success also included 15 or more sessions, starting program delivery in upper elementary or middle school and continuing into high school, and involving older peers (Flay, 2009). These reviews did not, however, address the potential of social competence and influence theories to prevent alcohol and illicit drug use.

With respect to programs targeting alcohol, one meta-analysis of interventions to reduce alcohol use in adolescents found that brief school-based interventions were effective in reducing adolescents’ alcohol use relative to controls (Hennessy and Tanner-Smith, 2015). Effectiveness was greatest with a motivational enhancement approach and with individual versus group programs. As most motivational enhancement programs were delivered individually, however, it was unclear whether group formats were not effective, or effective alcohol intervention strategies had not yet been used in a group format (Hennessy and Tanner-Smith, 2015). Another meta-analysis showed that program impacts were not affected by the intensity of program dosage or by program delivery in junior high versus high school (Strøm et al., 2014). Agabio and colleagues (2015) identified the Unplugged Program, an intervention delivered and tested in Europe,

as the alcohol prevention program with the most robust evidence base in the European context. Fewer school-based programs have targeted marijuana and illicit drug use in isolation. A meta-analysis of cannabis prevention programs did find small but significant effects, but not on intentions to use or refusal skills (Lize et al., 2017).

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses highlight that diverse strategies can be effective for substance use prevention, although not all strategies are equally beneficial across different types of substances. For instance, a recent meta-analysis found benefits for multicomponent school interventions—approaches that went beyond health education curricula to address social determinants of health, such as by altering the physical or social school environment or promoting health schoolwide (Shackleton et al., 2016). Multicomponent interventions were found to be effective in reducing smoking, but evidence for their impact on alcohol or drug use was limited. Approaches that integrate health-based education in substance use prevention skills within broader academic curricula also appear promising (Melendez-Torres et al., 2018). Another study found support for the effectiveness of universal resilience-building interventions aimed at enhancing at least one individual and one environmental protective factor for youth ages 5–18 in reducing illicit substance use, but not tobacco or alcohol use (Hodder et al., 2017). Peer interventions delivered in schools may also be an effective strategy for reducing the likelihood of using tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs (MacArthur et al., 2016).

The developmental timing of school-based substance use prevention merits careful attention. Onrust and colleagues (2016) attempted to resolve inconsistencies in the substance use prevention literature by assessing 288 universal and targeted programs for four different age groups (elementary school, early adolescence, middle adolescence, and late adolescence). Their findings were broadly consistent with prevailing hypotheses; they found that while some prevention strategies were effective across multiple age groups, most had differential effects based on the age group to which they were delivered. Across multiple age groups, students participating in universal interventions showed improvements in self-control, problem solving, and cognitive-behavioral skills, and students participating in targeted interventions showed improvements in social influence skills, refusal skills, and health education. However, the impact of other approaches varied significantly by participants’ ages. For instance, programs that explicitly included training related to substance use (e.g., refusal skills) were not effective with elementary school children, whereas training in basic social, self-control, and problem-solving skills worked well with that age group. By contrast, late adolescents benefited from universal programs that taught refusal skills using a social influences approach, consistent with the emphasis in late adolescence on developing one’s identity (Onrust et al., 2016) (see Box 4-4 for an example).

Bullying

Over the past decade, awareness has grown of the deleterious effects of bullying and cyberbullying—a subset of bullying that involves using electronic or digital media to hurt or socially isolate a victim—on students’ social, emotional, and academic development.12 It is estimated that between 18 and 31 percent of youth have experienced bullying in school, and 5 to 15 percent of youth have experienced cyberbullying. Some subgroups of young people are at particular risk; for instance, data suggest sexual minority and gender minority youth experience bullying victimization significantly more often than do heterosexual and cisgender youth (Reisner et al., 2014; Robinson, Espelage, and Rivers, 2013). Many states have passed antibullying legislation, and bullying prevention programs have been instituted in schools across the country (see Box 4-5 for an example). A number of the social-emotional learning interventions and universal interventions aimed at preventing disruptive behaviors discussed above also can prevent bullying; this section reviews only those programs for which outcomes related to bullying have been specifically measured.

Researchers have examined school-wide efforts to address bullying and support affected students (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016). The authors found that the most effective bullying prevention programs include multiple components and are implemented schoolwide, meaning that all school staff, teachers, and administrators adopt the practices within a school. The report also cautions that certain practices and policies, such as routine use of out-of-school discipline, as is seen with zero tolerance policies, should not be the primary strategy for responding to bullying incidents. Given the power differential inherent in bullying, peer mediation and encouraging students who have been targeted by bullying to “fight back” may also be harmful practices.

Several recent meta-analyses of school-based bullying prevention programs have shown small to moderate effects (Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2016; Lee, Kim, and Kim, 2015; Yeager et al., 2015), with stronger results for the more recently published studies (Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2016). Although some meta-analyses have found that bullying prevention programs that target younger children were more effective (Yeager et al., 2015), others have found that programs for older students did better (Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2016). Lee and colleagues (2015) found that those studies that taught emotional control had larger effect sizes on victimization than those without this training. Ttofi and Farrington (2011) conducted a meta-analysis of 44 studies and found that school-based bullying

___________________

12 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines bullying as “any unwanted aggressive behavior(s) by another youth or group of youths who are not siblings or current dating partners that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated. Bullying may inflict harm or distress on the targeted youth including physical, psychological, social, or educational harm” (Gladden, 2014, p. 7).

prevention programs lowered bullying by 20 to 23 percent and victimization by 17 to 20 percent. They concluded that more intensive programs, those with parent involvement, and those that involved greater playground supervision were more effective. Evans and colleagues (2014), however, concluded from their systematic review of school-based bullying prevention programs that results were mixed; 45 percent of studies showed no program effects on bullying perpetration, and the

authors question the measurements in studies of programs that did show effects. They note that the program with the strongest effects was from Finland and was tested on a homogeneous population; when bullying prevention programs have been tested in the United States with culturally diverse youth, results have been mixed.

Another meta-analysis focuses on bystanders, defined as those who witness bullying but do not participate on behalf of either the bully or the victim. Research on the role of bystanders in the social context of bullying has shown that intervening with bystanders can be key, given that they represent such a large proportion of students (Polanin, Espelage, and Pigott, 2012).

A recent meta-analysis of the relationship between bullying and victim suicide indicated that bullying is related to both suicidal ideation and attempts, and that cyberbullying is more strongly associated with suicidal ideation than general bullying is (Van Geel, Vedder, and Tanilon, 2014). Given the relatively recent identification of this latter type of bullying, few studies have been conducted on its prevention. However, evidence suggests that general bullying prevention can also decrease cyberbullying and cyber victimization (Gradinger et al., 2015).

Violence

As schools attempt to maintain a safe and supportive campus, strategies for violence prevention can be of utmost importance. Schools are relatively safe places, with less than 2.6 percent of all youth homicides occurring on a school campus (Zhang, Musu-Gillette, and Oudekerk, 2016).13 However, about 20 percent of students report being bullied at school, and 7.8 percent are involved in a physical fight (Kann et al., 2016).

Schools have a number of strategies for preventing violence before it happens through universal prevention programs, such as those that target disruptive behaviors and bullying, discussed earlier. In addition, a number of interventions that prevent substance use disorders also prevent aggression and violent behavior (Bavarian et al., 2013, 2016; Botvin, Griffin, and Nichols, 2006). A recent meta-review of youth violence prevention programs (Matjasko et al., 2012) found that school-based programs consisting of classroom curricula and peer mediation, conflict resolution, and conduct behavior modification programs generally had moderate to strong effects on youth violence–related outcomes.

Despite evidence of effective MEB health promotion and MEB disorder prevention programs, schools continue to use out-of-school discipline, such as suspension and expulsion, inappropriately for such common disruptive behaviors as defiance and noncompliance. School staff also mete out discipline unevenly,

___________________

13 Although multiple-victim shootings in the United States are on the rise in general, that is not the case in schools. There is an average of about one per year across the nation’s 100,000 schools. In the 1992–1993 school year, about 0.55 students per million were shot and killed; in 2014–2015, that rate was closer to 0.15 per million (Fox and Fridel, 2019).

disproportionately disciplining African American youth (Skiba et al., 2014). For example, although African American males make up just 8 percent of U.S. enrolled students, they represent 25 percent of students with suspensions (U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, 2014). Some link high and disproportionate rates of out-of-school discipline for African American students with other forms of social disadvantage (Meek and Gilliam, 2016). Increasing the use of strategies to improve school climate and social-emotional learning may mitigate overuse of out-of-school discipline (Osher et al., 2010); national policy recommendations outline nondiscriminatory administration of school discipline (U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. Department of Education, 2014).

Another alternative to out-of-school discipline has been the dissemination in schools of restorative justice practices, which are based on practices observed in indigenous communities (Anfara, Evans, and Lester, 2013; Johnstone, 2011). This approach involves fostering dialogue between students involved in a conflict and encouraging participation of victims and offenders in resolving a conflict (Zehr, 2002). Although no rigorous evaluations of restorative justice practices have yet been published, practice-based evidence indicates that reductions in suspensions and referrals for violent behavior may be attributable to these practices, which are becoming increasingly common in the United States. Further research in this area would be a valuable contribution (Davis, 2014; Song and Swearer, 2016).

Schools have access to a range of strategies for responding to violence and other school crises, although there is little empirical evidence of effectiveness for many of these strategies (Kataoka et al., 2012). One promising crisis response strategy in schools is Psychological First Aid, a brief teacher-led intervention that provides guidance for teachers to enhance their connectedness with students following a crisis (Pynoos and Nader, 1988; Ramirez et al., 2013; Schreiber, Gurwitch, and Wong, 2006). In a 2012 RCT, the Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines for determining next steps following a student threat of violence were compared with care as usual (Cornell, Allen, and Fan, 2012). Use of this threat assessment tool led to greater use of mental health services, better engagement with parents, and fewer school suspensions among students making these threats. Further research is needed to guide schools regarding best practices before, during, and after a school crisis.

Researchers have also focused on interventions to prevent teen dating violence. Box 4-6 describes an example of one such intervention. Teen dating violence is common, affecting 21 percent of female and 10.4 percent of male adolescents who date (Vagi et al., 2015). Interventions to support the development of healthy relationships in early adolescence are important, especially given that teen dating violence predicts later heavy episodic drinking, depressive symptoms and suicidality, smoking, and intimate partner violence as a young adult (Exner-Cortens, Eckenrode, and Rothman, 2013). Low and colleagues (2013) offer a social-ecological model of risk and protective factors for dating violence. These include individual factors such as attitudes about violence and myths about rape,

family factors such as parenting style, exposure to violence and maltreatment, peer support of dating violence, and school policies.

School-based preventive interventions for teen dating violence are universal, with educational components that attempt to change the school culture by promoting respect and lessening aggression. A meta-analysis of 23 studies of interventions to prevent teen dating violence among middle and high school students found improvements in knowledge and attitudes but not consistent changes in rates of dating violence and victimization (De La Rue et al., 2016).

Another study, however, did document change in dating violence behavior (Miller et al., 2013). In Coaching Boys Into Men, high school male athletes received weekly, brief violence prevention messages from their trained athletic coach (Miller et al., 2012). At 1-year follow-up, youth in the intervention compared with those in the control group perpetrated less dating violence and engaged in less negative bystander behavior (Miller et al., 2013).

Overall, a wealth of school-based prevention strategies can address youth violence broadly, with multiple interventions showing positive effects on various types of violence (Foshee et al., 2014) and on high-risk behaviors associated with youth violence, including delinquency, substance use, and sexual risk behaviors (Beets et al., 2009; Botvin, Griffin, and Nichols, 2006; David-Ferdon and Simon, 2014). Cross-cutting prevention strategies that result in the prevention of multiple health risk behaviors may be the most efficient targets for the limited resources available in schools.

Suicide

The suicide of a student, although a rare event, can have devastating repercussions on a campus and pose a minor but significant risk of social contagion (Gould, Jamieson, and Romer, 2003). Unfortunately, as discussed in

Chapter 2, suicide among adolescents has been rising over the past decade (Simon, 2017), and it was recently estimated to be the second leading cause of death among adolescents and transitional-age youth (those ages 15–24) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). Among girls ages 15–19, the rate of suicide doubled from 2007 to 2015 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014; De Silva et al., 2013; Katz et al., 2013). Rates of suicidality and depressive symptoms were also found to be higher in sexual minority as compared with heterosexual adolescents, and the increased risk for sexual minority youth persists through the transition to adulthood (Marshal et al., 2013).

In a recent review of school-based suicide prevention programs, the authors conclude that data in support of suicide prevention in schools are limited, with only two programs—Signs of Suicide and the Good Behavior Game—demonstrating effects on reducing suicide attempts (Katz et al., 2013). Signs of Suicide, which has been studied in middle and high school students, aims to increase knowledge and attitudes about depression, encourage individual and peer help-seeking, reduce stigma around mental illness and help-seeking, engage teachers and parents in gatekeeping activities, and encourage schools to expand mental health partnerships and services (Aseltine and DeMartino, 2004; Schilling et al., 2014). Evaluation of this suicide intervention at 3-month follow-up found that those who received Signs of Suicide were 64 percent less likely to report a suicide attempt compared with the control group and had improved knowledge and attitudes about intervening with friends who were suicidal. They were also more likely to seek help themselves (Schilling, Aseltine, and James, 2016).

The Good Behavior Game, discussed earlier (refer to Box 4-3), although not developed with the explicit aim of reducing youth suicidal thoughts, behaviors, or attempts, has been found to have multiple long-term benefits for participating young people. For instance, a young adult follow-up of students who had participated in the Good Behavior Game during elementary school found reductions in suicidal ideation and attempts for both males and females (Wilcox et al., 2008).

School Dropout

Dropping out of school has long-term adverse impacts over the life course, and there are persistent racial and socioeconomic disparities in high school graduation rates (McFarland et al., 2019; Rumberger, 2011; Rumberger et al., 2017). Some dropout prevention programs target individual students or small student groups, whereas others target whole schools. A meta-analysis of general dropout prevention programs (152 studies) showed that programs generally increased high school completion if implemented with fidelity, but that no particular program or approach emerged as clearly superior (Wilson et al., 2011). However, findings from the Institute of Education Sciences What Works Clearinghouse (Rumberger et al., 2017) and work by other researchers (Mac Iver and Mac Iver, 2009) indicate that specific approaches may be particularly beneficial, including early interventions, whole-school multitiered systems of

support, and multicomponent programs suitable for reaching different subgroups of youth at risk for high school dropout.

Relatively few programs have these features: most interventions are currently single-component, address individual students or small groups, and are delivered in high school (Freeman and Simonsen, 2015). There is a need for more multitiered approaches that address distinct subgroups of youth to be implemented and rigorously evaluated. Strategies to promote academic achievement and readiness for employment or postsecondary education are also critical, as standardized testing data indicate that many students are not proficient at core academic competencies (McFarland et al., 2019), and many high school graduates are deficient in key skills for future success. Integration of programs to prevent emotional and behavioral problems with dropout prevention and academic achievement promotion strategies—and assessment of emotional, behavioral, and academic outcomes—is also an important direction for future research, so that programs can be well aligned and efficiently integrated within school settings.

POSTSECONDARY SETTINGS

Prevention strategies have also been developed and tested in higher education settings. College-age young people often live apart from their families and have increasing independence to make decisions about their own lives. Those attending college are generally exposed to many opportunities to engage in potentially harmful behavior, including alcohol and drug use and risky sexual behavior. This is also a period of life when the onset of such psychiatric disorders as depression and anxiety is common and can have serious negative impacts on academic and social functioning.

Most preventive interventions in the college setting target alcohol use. In a meta-analytic review of 41 RCTs that examined strategies to prevent and reduce alcohol use in the first year of college, many programs were found to be efficacious for reducing alcohol use and related problems (Scott-Sheldon et al., 2014). The inclusion of such features as personalized feedback and goal setting was associated with better outcomes. By contrast, meta-analytic reviews have concluded that interventions targeting social norms (Foxcroft et al., 2015) or using motivational interviewing (Foxcroft et al., 2016) have no meaningful benefits for preventing alcohol misuse in young people up to age 25. Reviews have also evaluated features of intervention delivery that may be differentially associated with outcomes. For instance, a narrative review found that interventions targeting young adults’ expectations regarding the likely outcomes of alcohol use were most effective when delivered to all-male student groups (Labbe and Maisto, 2011). A meta-analytic review comparing computer-delivered and face-to-face alcohol interventions reported superior performance for the latter (Carey et al., 2012). And a review of only seven mobile interventions to prevent and reduce risky drinking in college students notes variable findings and concludes that further development and testing of mobile interventions is needed (Berman et al., 2016).

Interventions have also addressed mental health, with a focus on depressive and anxiety symptoms and stress. A meta-analysis of universal mental health prevention programs in higher education identified 103 RTCs of interventions for college, graduate, and professional students (Conley, Durlak, and Kirsch, 2015). Skills-training programs with opportunities for supervised practice showed promising effects on psychological symptoms and outperformed both skills-training programs without supervised practice and programs that provided psychoeducation (Conley, Durlak, and Kirsch, 2015).

Some prevention programs addressing psychological symptoms are delivered using technology. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 RCTs of computer- or web-based interventions to prevent depression, anxiety, or stress found significant overall effects for these interventions when compared with inactive controls (i.e., those receiving no treatment) but not active controls (i.e., those who received materials designed to mimic the attention received by participants assigned to an intervention) (Davies, Morriss, and Glazebrook, 2014), which suggests that benefits may not relate to hypothesized core intervention components. A more recent meta-analysis of technology-delivered preventive interventions in higher education identified 22 universal and 26 indicated interventions as well supported; indicated interventions that provided support in person, online, or via e-mail produced better outcomes than those that did not (Conley et al., 2016).

Very few suicide prevention programs have been tested in higher education. A 2014 Cochrane systematic review identified only eight studies testing interventions for the primary prevention of suicide in postsecondary students (Harrod et al., 2014). Included studies were heterogeneous with respect to design, content, and findings. Five of the studies had a high risk of bias, and the authors concluded that the evidence was not sufficient to support any suicide prevention program or policy.

SUMMARY

Because young people spend so much of their time in school and are significantly influenced by their school experiences, this is a critical setting for efforts to both promote healthy MEB development and prevent MEB disorders. A wide variety of research has explored efforts for students from preschool through postsecondary education, although the research varies somewhat in rigor, and certain areas have been studied more comprehensively than others. Findings consistently indicate that school-based interventions for promotion of MEB health and prevention of MEB problems are both feasible and beneficial. A great deal of work remains to be done in determining how best to integrate different evidence-based intervention approaches so that they can be delivered across development and can efficiently target multiple risk and protective factors that promote MEB health across multiple social, emotional, and behavioral domains.

REFERENCES

Abry, T., Rimm-Kaufman, S.E., Larsen, R.A., and Brewer, A.J. (2013). The influence of fidelity of implementation on teacher-student interaction quality in the context of a randomized controlled trial of the responsive classroom approach. Journal of School Psychology, 51(4), 437–453.

Adams, G., Zaslow, M., and Tout, K. (2007). Early care and education for children in low-income families. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Administration for Children and Families. (n.d.). Early Head Start research and evaluation project (EHSRE), 1996–2010. Available: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/research/project/early-head-start-research-and-evaluation-project-ehsre-1996-2010.

Administration for Children and Families. (2002). Making a difference in the lives of infants and toddlers and their families: The impacts of Early Head Start volume I: Final technical report. Washigton, DC: Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation.

Agabio, R., Trincas, G., Floris, F., Mura, G., Sancassiani, F., and Angermeyer, M.C. (2015). A systematic review of school-based alcohol and other drug prevention programs. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, 11(Suppl. 1 M6), 102–112.

Ahlen, J., Lenhard, F., and Ghaderi, A. (2015). Universal prevention for anxiety and depressive symptoms in children: A meta-analysis of randomized and cluster-randomized trials. Journal of Primary Prevention, 36(6), 387–403.

Albert, D., Belsky, D.W., Crowley, D.M., Bates, J.E., Pettit, G.S., Lansford, J.E., Dick, D., and Dodge, K.A. (2015). Developmental mediation of genetic

variation in response to the fast track prevention program. Development and Psychopathology, 27(1), 81–95.

Aldana, S.G., Merrill, R.M., Price, K., Hardy, A., and Hager, R. (2005). Financial impact of a comprehensive multisite workplace health promotion program. Preventive Medicine, 40(2), 131–137.

Anfara, V.A., Evans, K.R., and Lester, J.N. (2013). Restorative justice in education: What we know so far. Middle School Journal, 44(5), 57–63.

Aseltine, R.H., Jr., and DeMartino, R. (2004). An outcome evaluation of the SOS suicide prevention program. American Journal of Public Health, 94(3), 446–451.