5

Strategies for Health Care Settings

Visits to a medical office or clinic provide an ideal opportunity for delivering many kinds of supports for children’s mental, emotional, and behavioral (MEB) health and development. In pediatric primary care settings, children are seen on repeated occasions for well-child care, at which time parents may receive education and support (anticipatory guidance). Clinicians have a chance to build trusting relationships with patients and their families during frequent well-child visits in the first 2 years, and perform less frequent surveillance and scheduled periodic assessments for healthy development of children thereafter (Leslie et al., 2016). Also important is the frequent contact that pregnant and postpartum women have with the health care system, where they can receive guidance for safe gestation and preparation for supporting healthy child development, as well as early intervention for such risks as parental depression and concerning lifestyle and home environments at a time when the fetus and child are undergoing rapid brain development (Shonkoff et al., 2012). Care that addresses the family as a unit can help foster the parent–child connection and the resilience of children and families.

Indeed, health care settings provide opportunities to support families at every stage that have the potential to influence a child’s MEB development—from before conception and throughout development, including

- preconception and prenatal health care involving both mother and father;

- child health care starting at birth and extending into young adulthood, including well-child care as well as care for acute and chronic conditions;

- health care for adolescents and young adults in the childbearing years; and

- parental health maintenance.

This array of opportunities could have a significant impact, but there is a notable gap between these possibilities and the reality of many health care settings. Neither health care personnel nor the health care system take full advantage of the opportunity to contribute systematically to improvement of the

MEB development of children and youth. Overall rates of developmental screening and surveillance remain low (Coker, Shaikh, and Chung, 2012; Hirai et al., 2018). Barriers to success also include a paucity of behavioral training for health professionals to carry out this work in primary care settings and low levels of reimbursement for preventive and behavioral pediatric care in office-based settings. Further, the health care system is not equipped to improve MEB health in children on its own and would benefit from partnerships with other community efforts.

While efforts to comprehensively improve child MEB development are not yet regularly included in health care for children, youth, and families, there is growing interest in how this might be accomplished. For example, interdisciplinary teams in primary care allow practices to attend more easily to all dimensions of health, including MEB development (Boat et al., 2016; Leslie et al., 2016). These teams often include

- physicians from various disciplines, such as pediatrics, family medicine, obstetrics/gynecology, and psychiatry;

- nurses and advance practice nurses;

- clinical psychologists and other behavioral health professionals;

- social workers, particularly those with behavioral health training and experience; and

- parent counselors, community health workers, peer parenting advocates, and other paraprofessionals.

Efforts to integrate primary child health care clinics and home visitation programs can enhance previsit planning of well-child visits in order to ensure that those visits address family needs and concerns, and also provide a way to monitor and enhance family attention to health care plans. Another example is embedding child, parent, and family community services into health care settings to provide “one-stop shopping” to address family MEB health needs. A third example is health care systems that partner with preschool and school health care programs. In this chapter we review the possibilities for universally fostering MEB health in health care settings, beginning with preconception health care. We close with a summary discussion of the issues that make this avenue for achieving population-level improvements challenging.

PRECONCEPTION HEALTH CARE

An important strategy to foster the MEB health of children and youth is to optimize the physical, behavioral, and social health of prospective parents and minimize the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. This strategy has been termed “three-generation health” because it has potential benefits for parents, their children, and those children’s future children (Cheng, Johnson, and Goodman,

2016). However, few evidence-based programs based on this strategy have been developed and implemented.

There are a number of challenges for delivering care that directly benefits the health of future parents. Young people in general participate in organized health care inconsistently, and participation is least likely among adolescent and young adult males. Young women seek care in a number of health care settings, including gynecology, pediatric adolescent medicine, internal medicine, and family medicine. However, those who most need health surveillance and advice during the preconception period are the least likely to connect with the health care system (Bish et al., 2012). Family health care is often segmented across separate systems that serve children and adults. Discontinuity in insurance and funding programs and limited training programs for providers are additional challenges. Although schools and school health clinics provide an opportunity to improve preconception health (Charafeddine et al., 2014), the involvement of additional community partners, including public health systems, will likely be needed to bring preconception care to the populations who most need it (Shannon et al., 2014).

Nevertheless, preconception reproductive risk assessments in primary care settings have had some positive results. A systematic review of studies of multiple- or single-component interventions for preconception health assessment found evidence for improved maternal self-efficacy, locus of control, and risk behavior that are pertinent to mothers’ ability to provide the nurturance children require, although the authors were unable to draw any conclusions about the effects of the interventions on adverse pregnancy outcomes (Hussein, Qureshi, and Kai, 2014).

Several public health models of preconception care have been proposed (Shannon et al., 2014). In 2004, the Preconception Health and Health Care (PCHHC) initiative extended the length of maternity care to include the period prior to pregnancy (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). To reinforce this idea, the PCHHC initiative published A National Action Plan for Promoting Preconception Health Care in the United States (Floyd et al., 2013). This action plan provides a model for use by states, communities, and public or private organizations in strategic planning for preconception care projects.

The PCHHC initiative proposed measures for assessing preconception wellness and sharing information related to pregnancy intention and planning, access to care, preconception use of a multivitamin with folic acid, tobacco avoidance, controlling depression, healthy weight, the absence of sexually transmitted infections, optimal glycemic control in women with pregestational diabetes, and avoidance of medications that disturb the growth and development of a fetus (Frayne et al., 2016). Implementation and outcome reports for the PCHHC initiative will help determine whether increased attention to preconception health can foster safe, stable, and nurturing environments and healthy MEB development in children at a population level.

PRENATAL HEALTH CARE

Several MEB development risk factors are associated with the prenatal period. The most common of these is preterm birth (see Chapter 2); fetal exposures to toxic substances and maternal adverse health conditions also pose significant risks. Despite evidence that promotion of healthy pregnancy and prevention of in utero risks support healthy MEB outcomes in children, relatively modest progress has been made toward these goals. Therefore, more comprehensive access to medical surveillance and care for women in the early stages of pregnancy is an important opportunity to improve children’s MEB health.

Preterm Birth

Overall, premature birth has occurred in nearly 10 percent of U.S. pregnancies over the last several decades and the United States has had among the highest prevalence of preterm births in the world (Blencowe et al., 2012). However, there are large disparities by race and ethnicity. Black women have a preterm birth rate that is 49 percent higher than that of white women (13.4% compared with 8.9%); Asians/Pacific Islanders have the lowest percentage of preterm births (8.6%) (March of Dimes, 2018). The percentage of preterm births for Hispanics is 9.2 percent, while that of American Indians/Alaska Natives is below the national average at 10.8 percent (March of Dimes, 2018).

Many children born prematurely are at high risk for concerning neurobehavioral outcomes that currently are not preventable, although recent work has focused on identifying therapeutic agents that may protect brain development in preterm babies (Mürner-Lavanchy et al., 2018; Schang, Gressens, and Fleiss, 2014). The causes are genetic and environmental factors (Zhang et al., 2018), and researchers are pursuing understanding of contributing biological pathways as well as means of detecting and mitigating the risk for premature birth.

The risk factors that are known to be associated with preterm birth include maternal inflammatory conditions (Cappelletti et al., 2016), smoking during pregnancy (Wisborg et al., 1996), maternal disordered sleep (Felder et al., 2017), maternal stress (Wadhwa et al., 2011), and maternal anxiety and depression (Staneva et al., 2015). Multiple pregnancies, which occur more frequently with assisted reproductive technologies, are more likely to result in preterm deliveries (Barri et al., 2011).

Each of these risk factors may be amenable to prevention interventions, but evidence for effective interventions is limited. Interventions that may be effective include

- a stress-coping software application for hospitalized pregnant women at risk for premature labor (Jallo et al., 2017); and

- providing financial supports to low-income families (Beauregard et al., 2018).

Other interventions have proved beneficial for supporting the health and development of preterm babies. These include home visiting programs that target parent–child interactions, which provide short-term benefits for the healthy development of preterm babies (see Chapter 9 for an example) (Goyal, Teeters, and Ammerman, 2013) and providing early intervention services for children born prematurely until their entry into school (Chung, Opipari, and Koolwijk, 2017).

Some positive results have been shown for efforts to provide universal and anticipatory health care and support reproductive choice starting before or early in pregnancy, and for community-level efforts to address health risks associated with preterm birth. For example, the banning of tobacco smoking in public spaces and workplaces and measures to improve access to long-acting reversible contraceptives have both been associated with declines in rates of preterm birth in European countries (Been et al., 2014; Cox et al., 2013; Mackay et al., 2012; Simón et al., 2017).

Adverse Exposures and Conditions

In utero exposure to a long list of toxins and medications, including tobacco smoke, alcohol, opioids, and other substances of abuse, and prescription drugs such as antiepileptics and antidepressants, is known to affect fetal brain development adversely and can interfere with children’s healthy MEB development. Maternal health problems that pose risks for the fetus include poor nutrition; obesity; stress; and mental disorders, especially anxiety and depression. Rigorous surveillance of maternal health is key to mitigating these risks, which reinforces the importance of prenatal health care starting from the earliest possible time after conception.

Some of these adverse exposures are better understood than others. For example, the adverse effects on fetuses and young children of exposure to any level of lead has received considerable attention (Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2012). Perhaps less well known is that maternal obesity prior to conception is associated with adverse neurobehavioral effects in the child, including attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorders, and cognitive delays (Harmon and Hannon, 2018), and is a risk factor for premature birth as well. Insufficient or rapid weight gain during pregnancy also has adverse effects on neurobehavioral outcomes (Aubuchon-Endsley et al., 2017). Optimal nutrition during pregnancy has many dimensions, and close monitoring by the health care system is an important means of tracking whether expectant mothers are progressing optimally in this regard. Women of low socioeconomic status are at greatest risk for suboptimal nutrition because of poor access to both healthy food and nutritional guidance by health care providers.

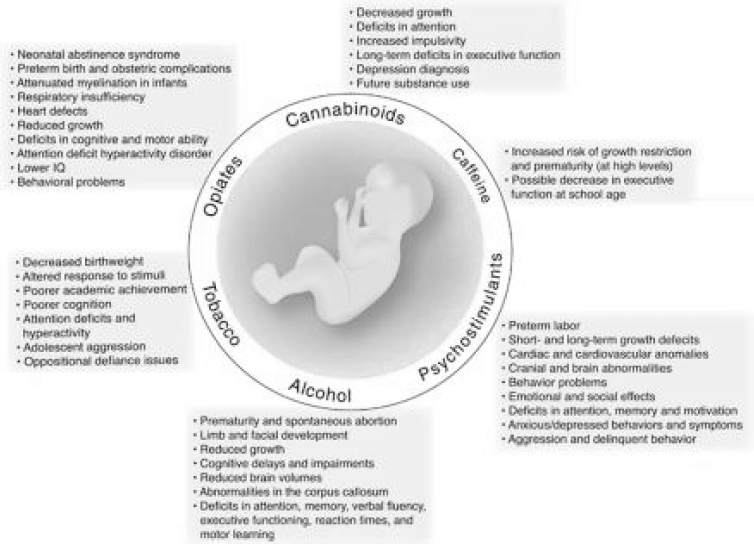

Perhaps the largest class of exposures is to legal and illegal drugs, including alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, psychostimulants, and opioids, which can cross the placenta and affect the brain development of a fetus and cause related harms. Some of these substances have effects at the molecular level that are different for the fetal brain than for adults, for example, and these effects may also interact

with environmental factors (Ross et al., 2015). Pregnant women who use such substances also frequently have MEB disorders, environmental stressors, and inconsistent prenatal care (Forray, 2016). Pregnant women’s exposure to these substances is widespread, although it varies by substance. Estimates vary, but a 2015 overview of the data found that among pregnant women ages 15–44, approximately

- 5.9 percent used illicit drugs;

- 17 percent had used cigarettes within the previous month, and 12 percent smoked throughout their pregnancies,1 with many more being exposed to secondhand smoke; and

- 12 percent reported having used alcohol within the previous month (Ross et al., 2015).

These exposures can cause a range of harms to the fetus, including to physical, cognitive, and emotional development, as well as an increased likelihood of low birthweight (Ross et al., 2015). The effects vary depending on the stage at which the fetus is exposed and other factors, but they can be severe; see Figure 5-1. Adverse developmental, cognitive, and behavioral outcomes related to fetal alcohol exposure have been estimated to affect 1.5 in every 100 children in the United States (Popova et al., 2016). This prevalence is approximately the same as that for autism spectrum disorder (Baio et al., 2018) and may be considerably higher in low-resourced populations (Bell and Chimata, 2015). Heavy consumption of alcohol also tends to be accompanied by poor nutrition, a factor that may contribute further to adverse fetal outcomes. Use of cocaine and amphetamines during pregnancy has been linked to adverse neurobehavioral outcomes for children and youth (Forray and Foster, 2015). Infants exposed to tobacco products in utero have demonstrated effects including irritability, poor self-regulation (requiring more caregiver attention), and other deficits; older children with such exposure show signs of attention deficit (Ross et al., 2015).

Evidence-based options for treating pregnant women who use potentially harmful substances during pregnancy or have substance use disorders exist, but are not currently adequate to address pregnant women’s needs (Bishop et al., 2017). Treatment approaches including cognitive-behavioral therapy; a community reinforcement approach; brief screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment; and 12-step programs and other types of support groups have been shown to be effective for various types of substance use, but in practice many facilities do not offer services tailored for pregnant women, and access is limited by a shortage of providers and other factors (Bishop et al., 2017).

___________________

1 A more recent estimate for the prevalence of smoking during pregnancy in the United States was 7 percent (Drake, Driscoll, and Mathews, 2018).

SOURCE: Ross et al. (2015).

The prevalence of smoking during pregnancy is concerningly high, and this practice is associated with a well-known array of adverse outcomes, including stunted fetal and postpartum growth and more frequent cognitive and behavioral concerns, including ADHD. The available information about supporting pregnant women who smoke illustrates some of the challenges. Mothers who smoke may not be aware or acknowledge publicly that they are pregnant, delaying any options for intervening to prevent fetal exposure to smoke. E-cigarettes have been touted as a safer substitute for tobacco smoking, but e-cigarettes and other nicotine delivery devices have not been shown to be safer for pregnant women, and may eventually increase smoking for women of childbearing age (Klein, 2018). While studies of different interventions for smoking cessation show that monetary incentives may be the most effective, the rate of cessation of this addictive behavior is low with any intervention (Halpern et al., 2018).

Preventing potentially harmful substance use during pregnancy and mitigating harm to children are key objectives, and there is evidence of benefit for some efforts to do both. For example, preconception health care that includes self-care strategies for limiting alcohol consumption in sexually active women may contribute to reduced fetal exposure to alcohol. And early identification and introduction of targeted interventions for affected children show promise for improving functional outcomes and mitigating secondary behavioral disabilities

(Chasnoff, Wells, and King, 2015). Early developmental intervention programs for the children of substance-using mothers have also shown promise (Lowe et al., 2017; Maguire et al., 2016). As discussed above, opioid, cocaine, and other illicit substance use before or during pregnancy has adverse effects on the fetus and postpartum child. Preventing the initiation of use is likely to have greater impact than treating pregnant women already affected. The Youth Risk Index is a validated instrument for us in primary health care settings to target early teens; it detects initiation or risk for initiation of substance use and has considerable potential for prevention if linked to an effective intervention program (Ridenour et al., 2015).

Past policy approaches to potentially harmful substance use during pregnancy have included punitive legal measures that have proved ineffective and sometimes harmful in themselves (Bishop et al., 2017). More recently, the focus has been on public health approaches that emphasize mitigating harm and promoting access to evidence-based care and services (Bishop et al., 2017). However, further research is needed to fill in the picture of how developing babies are affected by combinations of circumstances that include mothers’ substance use; the effectiveness of prevention and treatment options; and ways to increase public awareness of the potential risks of substance use in sexually active women, particularly those wishing to conceive.

Prenatal Parenting Education

Prenatal parenting education is an important tool for promoting healthy MEB development in children. One opportunity to provide prenatal parenting education is through classes organized by obstetric providers, including midwives. These widely popular classes focus on management of pregnancy and the birth process, but can also promote positive parenting. Prenatal visits at pediatric clinics, which are recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), are another opportunity to address the elements of positive parenting (Yogman et al., 2018). However, because this prenatal visit typically occurs only once during the pregnancy, its impact may be limited unless it is also linked to continuing discussion throughout postnatal visits. Parenting education within the health care system can be supplemented by evidence-based prenatal parenting programs such as Family Foundations and Centering Pregnancy (see Boxes 5-1 and 5-2, respectively).

POSTNATAL HEALTH CARE

Primary health care currently offers the best opportunity to address children’s early (0–3) MEB development at a population level. Nearly all children and their caregivers are seen in primary care settings for well-child visits, with multiple visits in the first 3 years of a child’s life: the AAP recommends up to 13 such visits. These well-child checks have generally focused on physical and developmental health outcomes such as growth and immunizations, but tracking of children’s socioemotional development is now increasingly being incorporated into pediatric primary care practice (Weitzman and Wegner, 2015). The most recent (fourth) edition of the AAP’s Bright Futures guidelines, which are used by

primary care providers including pediatricians, family medicine physicians, and nurse practitioners, addresses elements of child care and includes more content than previous editions on attending to socioemotional outcomes for children.

Multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary primary care has gradually been embraced, first by clinics serving children from underresourced families, and more recently by private practices. Participants in this approach to comprehensive care include nurses and nurse practitioners, social workers, behaviorally trained practitioners including child psychologists, and parenting specialists. Inclusion of behavioral practitioners has been initiated through collocation or integration models that place these individuals geographically at the practice site or embed them in the practice (Stancin and Perrin, 2014). The objective of collocation of behavioral practitioners has been the provision of “one-stop shopping” for families of children with behavioral health disorders, and this development should facilitate activities targeting integrated MEB health promotion. (See the discussion of integrated behavioral and primary health care in the next section.) Only recently, however, has increased attention been paid to screening for behavioral disorders, such as autism spectrum disorders for young children and depression in adolescents, and screening of parents (largely mothers) for risks associated with negative parenting practices (Briggs et al., 2014; Dubowitz et al., 2011). For example, all children enrolled in Medicaid (currently approximately 40% of U.S. children) are supposed to be screened for behavioral issues, but the majority of those children are not yet receiving that screening (Children’s Bureau, n.d.).3

Most approaches for targeting healthy MEB development and better socioemotional outcomes through primary care are in the experimental or early implementation stages. A systematic review of 44 studies of behavioral health interventions for families of children ages 0–5 delivered in primary care found mixed evidence about impact and pointed to questions not yet answered by research about their mechanisms, trust in the primary care provider with respect to MEB issues, and populations most likely to benefit (Brown, Raglin Bignall, and Ammerman, 2018). The evidence base for the effects of these activities in achieving improved parenting skills and improved child outcomes is nascent but growing, and thus far there is some evidence to support the efficacy of parenting programs that are linked to or embedded in primary care practice.

One rationale for such programs is that the practice providers can selectively identify parents in need of enhanced parenting knowledge and skills, and that as trusted professionals, they may be successful in efforts to advise parents to join a parenting group or class (Leslie et al., 2016). An example is offering the Incredible Years parenting classes, in which parents bring their children to both academic-site pediatric practices and private practices in the Boston area (Perrin et al., 2014). Improved parent and child outcomes were documented at 1 year in this experimental intervention, but the program was not sustained after the research

___________________

3 See https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/systemwide/bhw/federal/epsdt.

effort (National Research Council, 2014). A number of other programs have tested recruitment for parenting interventions within the primary health care setting and determined that they may offer advantages. These programs include the Chicago Parenting Project (Breitenstein et al., 2007); Family Checkup (Shaw, 2017); and Familias Unidas, which enrolled 90 percent of referred parents of adolescents who had been identified in primary care as being at risk for substance use and other risky behaviors (Pantin et al., 2009).

An example of a program that embeds parenting specialists in a practice site is Healthy Steps (see Box 5-3). Other programs that have been studied include

- Reach Out and Read, which targets verbal and cognitive development (discussed in Chapter 10); and

- the Video Interaction Project, which targets socioemotional development (Mendelsohn et al., 2018).

INTEGRATING BEHAVIORAL CARE AND PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

The importance of addressing both the MEB and physical health needs of children is increasingly recognized (Foy and American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Mental Health, 2010). The AAP reports that nearly one-third of pediatric office visits in the United States involve a behavioral concern about the

child. In a call to action, the American Board of Pediatrics has identified behavioral health as a critical but neglected dimension of children’s health, and has proposed stronger behavioral health training for future pediatricians (McMillan, Land, and Leslie, 2017). As noted above, many pediatric offices do offer screening for certain disorders (e.g., autism spectrum disorders and adolescent depression) although the evidence base for doing so is currently viewed by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force as weaker than the base for other kinds of screening (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2016). Pediatric offices also frequently work with schools to identify and treat uncomplicated ADHD (Epstein et al., 2010). But while pediatric offices use well-child checks to work with families on a long list of prevention interventions for adverse physical health outcomes, MEB health promotion and prevention of MEB disorders are currently, at best, only a small part of pediatric care.

Although many efforts to promote MEB health through primary health care exist, particularly for children in the first 2 to 3 years of life, the health care system is not systematically taking full advantage of such opportunities, particularly opportunities to work with other community partners. One reason is the organization and structure of child health care practices, and another is a reimbursement system that has compensated poorly, if at all, for promotion and risk prevention directed at healthy MEB development (Counts et al., 2018). Another challenge is that relatively few primary pediatric and family medicine child health care providers have been trained to address behavioral issues, particularly at the level of promotion or risk prevention (Boat, Land, and Leslie, 2017).

A number of innovative efforts to change this situation are notable and may signal a move toward fully integrated universal practice. One such effort has been to strengthen training to address behavioral health. As noted, this type of training has typically played a small part in pediatricians’ education, and has tended to target identification of behavioral disorders, not MEB health promotion and prevention of risks. Efforts are being made to address this lack. For example, as part of the implementation of the Triple P Parenting Program in Seattle, Washington (see Chapter 3), pediatric residents acquired knowledge and skills that translated into more effective interactions concerning parenting practices with the caregivers of their patients (McCormick et al., 2014). Another evidence-based intervention is the Safe Environment for Every Kid Program, which trains health professionals, including pediatric residents, to better address the psychosocial risks of child maltreatment (Dubowitz et al., 2011). The training of psychologists to participate as members of the care team for children and families in the primary care setting has also been described (Stancin and Perrin, 2014).

Some research has examined the full integration of behavioral care, oriented toward both promotion/prevention and diagnosis/treatment, in primary care settings (Boat, Land, and Leslie, 2017; Herbst, Burkhardt, and McClure, 2017). In these settings, child psychologists partner with the pediatricians in working with child and caretaker dyads at well-child visits. Emphasis is placed on promoting and modeling positive caregiver–child interactions, as well as coaching

caregivers to adopt positive parenting practices. Parents have embraced this model, and the rate at which caregivers and their children return to the next well-child appointment is higher for those families who spend time with the psychologist. Screening for maternal depression and socioemotional assessment of the child are carried out routinely. While MEB outcomes for children who receive this comprehensive intervention have not yet been reported, the feasibility and acceptability of combined physical and behavioral care have been demonstrated for a diverse population that is largely supported by Medicaid. Furthermore, both pediatric and psychology residents have the opportunity to observe and practice this mode of care.

Universal, comprehensive behavioral care in child primary health care practices may be one of the best opportunities to address the agenda of fostering MEB health in the first years of life at a population level. Challenges include demonstrating improved parenting and child MEB outcomes, as well as convincing child health training programs, health systems that largely control the practice of medicine in the United States, and payer organizations that this approach is programmatically and economically feasible and cost-beneficial.

Adolescent medicine and the care of children and youth with chronic medical conditions are two areas in which the integration of behavioral and medical care plays a key role.

Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine

As noted in Chapter 1, the lifetime prevalence of any mental disorder among adolescents is estimated to be 49.5 percent (National Institute of Mental Health, 2019). Furthermore, 1 in 25 adolescents has a substance use or abuse condition (American Addiction Centers, 2019) and suicide is the second leading cause of adolescent death (Heron, 2016). However, the ratio of board-certified adolescent medicine providers to adolescents is 0.8 to 100,000 (American Board of Pediatrics, 2018). While the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education began requiring that pediatric resident training include one block (4 weeks) in adolescent medicine in 1997, faculty to provide comprehensive training in adolescent issues are in short supply, and pediatric residents report unmet needs in this area; many never encounter common adolescent issues in the course of their training (Ruedinger and Breland, 2017). Thus, while behavioral medicine has emerged as a greater part of adolescent care, much work remains to be done in this area.

Promotion of emotional health and prevention of depression and anxiety in this population appear to be substantial health care needs. Screening and treatment for depression are important not only for the health of adolescents but also for the well-being of their future progeny, and need to be a routine part of practice. Increasing the size of the medical workforce for adolescent medicine, whether through internal medicine, family medicine, or pediatric pathways, will be critical for a robust response to adolescent MEB needs. Anxiety also has emerged as an increasingly frequent concern in adolescents. Currently, 10.2 percent of those ages

12–17 have anxiety problems (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, n.d.). College counseling services have reported large increases in students seeking assistance with anxiety (Center for Collegiate Mental Health, 2018). Preventive interventions, such as mind–body techniques and other self-monitoring and cognitive-behavioral practices, have been studied in student populations from the grade school to health professions school levels, with evidence for improved outcomes, at least in the short term (see Chapter 3) (Cotton et al., 2011).

Chronic Disease Care for Children and Youth

MEB disorders frequently co-occur with physical conditions that may cause stress to both the child and the family. Three to 5 percent of children and youth in the United States have a disabling or life-threatening chronic illness, and many more are considered to have special health care needs. This population of children has increased dramatically as medical technology has extended the life span of children with the most serious conditions (Perrin, Anderson, and Van Cleave, 2014). Often, the care burden results in home life that is disrupted and chaotic, and these children and their parents have a high prevalence of anxiety and depression (Quittner et al., 2014). Such cases add considerably to the MEB health burden in the United States, and the MEB needs of these families have only recently been recognized as an important target for pediatric subspecialty and chronic disease care (Boat, Filigno, and Amin, 2017).

Promoting family wellness in the face of devastating chronic disease by working with families on such lifestyle issues and better management of situational and chronic stress is possible in the context of most chronic medical care that is provided by teams of nurses, psychologists, social workers, dieticians, physical therapists, and physicians. In addition, screening of these families for such care needs as attention to behavioral disorders (Quittner et al., 2014) and socioeconomic adversities (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015) is being tested and implemented in practice. Further, many children with chronic disease do not succeed in school at a level that will allow them to prepare adequately for independent living and self-support, or are not adequately accommodated at their school. Therefore, partnerships between health care providers and schools to ensure a responsive school environment and academic success, a potent resilience factor, is another important opportunity (Cruden et al., 2016; Filigno et al., 2017).

SUMMARY

Strategies to promote optimal MEB development within the health care system have great potential and offer particular benefits for young children in low-resourced populations. Researchers have only begun to focus on some of the possibilities, while others are better established.

REFERENCES

American Addiction Centers. (2019). Alcohol and drug abuse statistics. Available: https://americanaddictioncenters.org/rehab-guide/addiction-statistics.

American Board of Pediatrics. (2018). Pediatric physicians workforce data book, 2017–2018. Chapel Hill, NC: American Board of Pediatrics.

Aubuchon-Endsley, N., Morales, M., Giudice, C., Bublitz, M.H., Lester, B.M., Salisbury, A.L., and Stroud, L.R. (2017). Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and gestational weight gain influence neonatal neurobehaviour. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(2). doi:10.1111/mcn.12317.

Baio, J., Wiggins, L., Christensen, D.L., Maenner, M.J., Daniels, J., Warren, Z., Kurzius-Spencer, M., Zahorodny, W., Robinson, C., Rosenberg, White, T., Durkin, M.S., Imm, P., Nikolaou, L., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., Lee, L.-C., Harrington, R., Lopez, M., Fitzgerald, R.T., Hewitt, A., Pettygrove, S., Constantino, J.N., Vehorn, A., Shenouda, J., Hall-Lande, J., Van Naarden, K., Braun, and Dowling, N.F. (2018). Prevalence of autism spectrum

disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 67(6), 1–23.

Barri, P.N., Coroleu, B., Clua, E., and Tur, R. (2011). Prevention of prematurity by single embryo transfer. Journal of Perinatal Medicine, 39(3), 237–240.

Beauregard, J.L., Drews-Botsch, C., Sales, J.M., Flanders, W.D., and Kramer, M.R. (2018). Preterm birth, poverty, and cognitive development. Pediatrics, 141(1), e20170509. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-0509.

Been, J.V., Nurmatov, U.B., Cox, B., Nawrot, T.S., van Schayck, C.P., and Sheikh, A. (2014). Effect of smoke-free legislation on perinatal and child health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 69(9), 521–523.

Bell, C.C., and Chimata, R. (2015). Prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders among low-income African Americans at a clinic on Chicago’s south side. Psychiatric Services, 66(5), 539–542.

Bish, C.L., Farr, S., Johnson, D., and McAnally, R. (2012). Preconception health of reproductive aged women of the Mississippi River delta. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(Suppl. 2), 250–257.

Bishop, D., Borkowski, L., Couillard, M., Allina, A., Baruch, S., and Wood, S. (2017). Pregnant women and substance use: Overview of research & policy in the United States. Washington, DC: The George Washington University Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health. Available: https://publichealth.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/downloads/JIWH/Pregnant_Women_and_Substance_Use_updated.pdf.

Blencowe, H., Cousens, S., Oestergaard, M.Z., Chou, D., Moller, A.-B., Narwal, R., Adler, A., Vera Garcia, C.V., Rohde, S., Say, L., and Lawn, J.E. (2012). National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: A systematic analysis and implications. The Lancet, 379(9832), 2162–2172. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673612608204.

Boat, T.F., Filigno, S., and Amin, R.S. (2017). Wellness for families of children with chronic health disorders. JAMA Pediatrics, 171(9), 825–826.

Boat, T.F., Land, M.L., and Leslie, L.K. (2017). Health care workforce development to enhance mental and behavioral health of children and youth. JAMA Pediatrics, 171(11), 1031–1032.

Boat, T.F., Land, M.L., Leslie, L.K., Hoagwood, K.E., Hawkins-Walsh, E., McCabe, M.A., Fraser, M.W., de Saxe Zerden, L., Lombardi, B.M., Fritz, G.K., Hawkins, J.D., and Sweeney, M. (2016). Workforce development to enhance the cognitive, affective, and behavioral health of children and youth: Opportunities and barriers in child health care training. NAM Perspectives, 6(11).

Breitenstein, S.M., Gross, D., Ordaz, I., Julion, W., Garvey, C., and Ridge, A. (2007). Promoting mental health in early childhood programs serving families from low-income neighborhoods. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 13(5), 313–320.

Briggs, R.D., Silver, E.J., Krug, L.M., Mason, Z.S., Schrag, R.D.A., Chinitz, S., and Racine, A.D. (2014). Healthy steps as a moderator: The impact of maternal trauma on child social-emotional development. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 2(2), 166–175.

Brown, C.M., Raglin Bignall, W.J., and Ammerman, R.T. (2018). Preventive behavioral health programs in primary care: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 141(5), e20170611.

Cappelletti, M., Della Bella, S., Ferrazzi, E., Mavilio, D., and Divanovic, S. (2016). Inflammation and preterm birth. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 99(1), 67–78.

Center for Collegiate Mental Health. (2018). 2017 annual report. University Park, PA: Penn State University.

Centering Healthcare Institute. (2019). CenteringPregnancy. Available: https://www.centeringhealthcare.org/what-we-do/centering-pregnancy.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Overview: Preconception health. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/preconception/overview.html.

Charafeddine, L., El Rafei, R., Azizi, S., Sinno, D., Alamiddine, K., Howson, C.P., Walani, S.R., Ammar, W., Nassar, A., and Yunis, K. (2014). Improving awareness of preconception health among adolescents: Experience of a school-based intervention in Lebanon. BMC Public Health, 14(774).

Chasnoff, I.J., Wells, A.M., and King, L. (2015). Misdiagnosis and missed diagnoses in foster and adopted children with prenatal alcohol exposure. Pediatrics, 135(2), 264–270.

Cheng, T.L., Johnson, S.B., and Goodman, E. (2016). Breaking the intergenerational cycle of disadvantage: The three generation approach. Pediatrics, 137(6).

Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. (n.d.). National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) data query. Available: www.childhealthdata.org and www.cahmi.org.

Children’s Bureau. (n.d.). Behavioral health and Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT). Available: https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/systemwide/bhw/federal/epsdt.

Chung, P.J., Opipari, V.P., and Koolwijk, I. (2017). Executive function and extremely preterm children. Pediatric Research, 82(4), 565–566. doi:10.1038/pr.2017.184.

Coker, T.R., Shaikh, Y., and Chung, P.J. (2012). Parent-reported quality of preventive care for children at-risk for developmental delay. Academic Pediatrics, 12(5), 384–390.

Committee on Obstetric Practice. (2012). Lead screening during pregnancy and lactation. Committee Opinion, 533.

Cotton, S.M., Luxmoore, M., Woodhead, G., Albiston, D.D., Gleeson, J.F.M., and McGorry, P.D. (2011). Group programmes in early intervention services. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 5(3), 259–266.

Counts, N.Z., Halfon, N., Kelleher, K.J., Hawkins, J.D., Leslie, L.K., Boat, T.F., McCabe, M.A., Beardslee, W.R., Szapocznik, J., and Brown, C.H. (2018). Redesigning provider payments to reduce long-term costs by promoting healthy development. NAM Perspectives, 8(4).

Cox, B., Martens, E., Nemery, B., Vangronsveld, J., and Nawrot, T.S. (2013). Impact of a stepwise introduction of smoke-free legislation on the rate of preterm births: Analysis of routinely collected birth data. British Medical Journal, 346, f441.

Cruden, G., Kelleher, K., Kellam, S., and Brown, C.H. (2016). Increasing the delivery of preventive health services in public education. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 51(4), S158–S167.

Drake, P., Driscoll, A.K., and Mathews, T.J. (2018). Cigarette smoking during pregnancy: United States, 2016. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db305.pdf.

Dubowitz, H., Lane, W.G., Semiatin, J.N., Magder, L.S., Venepally, M., and Jans, M. (2011). The Safe Environment for Every Kid Model: Impact on pediatric primary care professionals. Pediatrics, 127(4), e962–e970.

Epstein, J.N., Langberg, J.M., Lichtenstein, P.K., Altaye, M., Brinkman, W.B., House, K., and Stark, L.J. (2010). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder outcomes for children treated in community-based pediatric settings. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 164(2), 160–165.

Family Foundations. (n.d.). Family Foundations: The program. Available: https://famfound.net/the-program.

Felder, J.N., Baer, R.J., Rand, L., Jelliffe-Pawlowski, L.L., and Prather, A.A. (2017). Sleep disorder diagnosis during pregnancy and risk of preterm birth. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 130(3), 573–581.

Filigno, S.S., Strong, S., Hente, E., Elam, M., Mara, C., and Boat, T. (2017). Poster session abstracts. Pediatric Pulmonology, 52(S47), S214–S516.

Floyd, R.L., Johnson, K.A., Owens, J.R., Verbiest, S., Moore, C.A., and Boyle, C. (2013). A national action plan for promoting preconception health and health care in the United States (2012–2014). Journal of Women’s Health, 22(10), 797–802.

Forray, A. (2016). Substance use during pregnancy. F1000Research, 5, F1000 Faculty Rev-1887. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4870985. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7645.1.

Forray, A., and Foster, D. (2015). Substance use in the perinatal period. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(11), 91. doi:10.1007/s11920-015-0626-5.

Foy, J.M., and American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Mental Health. (2010). Enhancing pediatric mental health care: Algorithms for primary care. Pediatrics, 125(Suppl. 3), S109–S125.

Frayne, D.J., Verbiest, S., Chelmow, D., Clarke, H., Dunlop, A., Hosmer, J., Menard, M.K., Moos, M.K., Ramos, D., Stuebe, A., and Zephyrin, L. (2016). Health care system measures to advance preconception wellness: Consensus recommendations of the cinical workgroup of the preconception

health and health care initiative. Obstetrics and Gynocology, 127(5), 863–872.

Goyal, N.K., Teeters, A., and Ammerman, R.T. (2013). Home visiting and outcomes of preterm infants: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 132(3), 502–516.

Halpern, S.D., Harhay, M.O., Saulsgiver, K., Brophy, C., Troxel, A.B., and Volpp, K.G. (2018). A pragmatic trial of e-cigarettes, incentives, and drugs for smoking cessation. New England Journal of Medicine, 378(24), 2302–2310.

Harmon, H.M., and Hannon, T.S. (2018). Maternal obesity: A serious pediatric health crisis. Pediatric Research, 83(6), 1087–1089.

Herbst, R.B., Burkhardt, M.C., and McClure, J. (2017). Universal promotion of child behavioral health in primary care. Available: https://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/dbassesite/documents/webpage/dbasse_176126.p df.

Heron, M. (2016). Deaths: Leading causes for 2013. National Vital Statistics Reports, 65(2), 1–95.

Hirai, A.H., Kogan, M.D., Kandasamy, V., Reuland, C., and Bethell, C. (2018). Prevalence and variation of developmental screening and surveillance in early childhood. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(9), 857–866.

Hussein, N., Qureshi, N., and Kai, J. (2014). The effects of preconception interventions on improving reproductive health and pregnancy outcomes in primary care: A systematic review. Contraception, 90(3), 339.

Jallo, N., Thacker, L.R., 2nd, Menzies, V., Stojanovic, P., and Svikis, D.S. (2017). A stress coping app for hospitalized pregnant women at risk for preterm birth. MCN. The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 42(5), 257–262.

Klein, J.D. (2018). E-cigarettes: A 1-way street to traditional smoking and nicotine addiction for youth. Pediatrics, 141(1).

Leslie, L.K., Mehus, C.J., Hawkins, J.D., Boat, T., McCabe, M.A., Barkin, S., Perrin, E.C., Metzler, C.W., Prado, G., Tait, V.F., Brown, R., and Beardslee, W. (2016). Primary health care: Potential home for family-focused preventive interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 51(4 Suppl. 2), S106–S118.

Lowe, J., Qeadan, F., Leeman, L., Shrestha, S., Stephen, J.M., and Bakhireva, L.N. (2017). The effect of prenatal substance use and maternal contingent responsiveness on infant affect. Early Human Development, 115, 51–59. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.09.013.

Mackay, D.F., Nelson, S.M., Haw, S.J., and Pell, J.P. (2012). Impact of Scotland’s smoke-free legislation on pregnancy complications: Retrospective cohort study. PLoS Medicine, 9(3), e1001175.

Magriples, U., Boynton, M.H., Kershaw, T.S., Lewis, J., Rising, S.S., Tobin, J.N., Epel, E., and Ickovics, J.R. (2015). The impact of group prenatal care on pregnancy and postpartum weight trajectories. American Journal of

Obstetrics & Gynecology, 213(5), 688.e681–e689. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.06.066.

Maguire, D.J., Taylor, S., Armstrong, K., Shaffer-Hudkins, E., Germain, A.M., Brooks, S.S., Cline, G.J., and Clark, L. (2016). Long-term outcomes of infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Neonatal Network, 35(5), 277–286.

March of Dimes. (2018). 2018 premature birth report cards. Available: https://www.marchofdimes.org/mission/prematurity-reportcard.aspx.

McCormick, E., Kerns, S.E., McPhillips, H., Wright, J., Christakis, D.A., and Rivara, F.P. (2014). Training pediatric residents to provide parent education: A randomized controlled trial. Academic Pediatrics, 14(4), 353–360.

McMillan, J.A., Land, M., Jr., and Leslie, L.K. (2017). Pediatric residency education and the behavioral and mental health crisis: A call to action. Pediatrics, 139(1), e20162141.

Mendelsohn, A.L., Cates, C.B., Weisleder, A., Berkule Johnson, S., Seery, A.M., Canfield, C.F., Huberman, H.S., and Dreyer, B.P. (2018). Reading aloud, play, and social-emotional development. Pediatrics, 141(5), e20173393.

Minkovitz, C.S., Strobino, D., Mistry, K.B., Scharfstein, D.O., Grason, H., Hou, W., Ialongo, N., and Guyer, B. (2007). Healthy steps for young children: Sustained results at 5.5 years. Pediatrics, 120(3), 658–668.

Mürner-Lavanchy, I.M., Doyle, L.W., Schmidt, B., Roberts, R.S., Asztalos, E.V., Costantini, L., Davis, P.G., Dewey, D., D’Illario, J., Grunau, R.E., Moddemann, D., Nelson, H., Ohlsson, A., Solimano, A., Tin, W., and Anderson, P.J. for the Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity Trial Group. (2018). Neurobehavioral outcomes 11 years after neonatal caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. Pediatrics, (141)5, e20174047. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-4047.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2015). Mental disorders and disabilities among low-income children. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/21780.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2019). Mental illness. Available: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml.

National Research Council. (2014). Strategies for scaling effective family-focused preventive interventions to promote children’s cognitive, affective, and behavioral health: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/18808.

Pantin, H., Prado, G., Lopez, B., Huang, S., Tapia, M.I., Schwartz, S.J., Sabillon, E., Brown, C.H., and Branchini, J. (2009). A randomized controlled trial of Familias Unidas for Hispanic adolescents with behavior problems. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(9), 987–995.

Perrin, E.C., Sheldrick, R.C., McMenamy, J.M., Henson, B.S., and Carter, A.S. (2014). Improving parenting skills for families of young children in pediatric settings: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(1), 16–24.

Perrin, J.M., Anderson, L.E., and Van Cleave, J. (2014). The rise in chronic conditions among infants, children, and youth can be met with continued health system innovations. Health Affairs, 33(12), 2099–2105.

Popova, S., Lange, S., Shield, K., Mihic, A., Chudley, A.E., Mukherjee, R.A.S., Bekmuradov, D., and Rehm, J. (2016). Comorbidity of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 387(10022), 978–987.

Quittner, A.L., Goldbeck, L., Abbott, J., Duff, A., Lambrecht, P., Sole, A., Tibosch, M.M., Bergsten Brucefors, A., Yuksel, H., Catastini, P., Blackwell, L., and Barker, D. (2014). Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with cystic fibrosis and parent caregivers: Results of the international depression epidemiological study across nine countries. Thorax, 69(12), 1090–1097.

Ridenour, T.A., Willis, D., Bogen, D.L., Novak, S., Scherer, J., Reynolds, M.D., Zhai, Z.W., and Tarter, R.E. (2015). Detecting initiation or risk for initiation of substance use before high school during pediatric well-child check-ups. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 150, 54–62.

Ross, E.J., Graham, D.L., Money, K.M., and Stanwood, G.D. (2015). Developmental consequences of fetal exposure to drugs: What we know and what we still must learn. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 40(1), 61–87.

Ruedinger, E., and, Breland, D. (2017). Resident desires and perceived gaps in adolescent health training. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(2), S52. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.10.286.

Schang, A.L., Gressens, P., and Fleiss, B. (2014). Revisiting thyroid hormone treatment to prevent brain damage of prematurity. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 92(12), 1609–1610.

Shannon, G.D., Alberg, C., Nacul, L., and Pashayan, N. (2014). Preconception healthcare delivery at a population level: Construction of public health models of preconception care. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(6), 1512–1531.

Shaw, D.S. (2017). The use of the family check-up in pediatric care: The safekeeping youth and smart beginning projects. Paper presented at the Society for Prevention Research.

Shonkoff, J.P., Garner, A.S., Siegel, B.S., Dobbins, M.I., Earls, M.F., McGuinn, L., Pascoe, J., and Wood, D.L. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246. doi:10.1542/peds/2011-2663.

Simón, L., Pastor-Barriuso, R., Boldo, E., Fernández-Cuenca, R., Ortiz, C., Linares, C., Medrano, M.J., and Galán, I. (2017). Smoke-free legislation in Spain and prematurity. Pediatrics, 139(6), e20162068.

Stancin, T., and Perrin, E.C. (2014). Psychologists and pediatricians: Opportunities for collaboration in primary care. American Psychologist, 69(4), 332–343.

Staneva, A., Bogossian, F., Pritchard, M., and Wittkowski, A. (2015). The effects of maternal depression, anxiety, and perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth: A systematic review. Women and Birth, 28(3), 179–193.

Trotman, G., Chhatre, G., Darolia, R., Tefera, E., Damle, L., and Gomez-Lobo, V. (2015). The effect of centering pregnancy versus traditional prenatal care models on improved adolescent health behaviors in the perinatal period. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 28(5), 395–401.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2016). Autism spectrum disorder in young children: Screening. Available: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/autism-spectrum-disorder-inyoung-children-screening.

Wadhwa, P.D., Entringer, S., Buss, C., and Lu, M.C. (2011). The contribution of maternal stress to preterm birth: Issues and considerations. Clinics in Perinatology, 38(3), 351–384.

Weitzman, C., and Wegner, L. (2015). Promoting optimal development: Screening for behavioral and emotional problems. Pediatrics, 135(2), 384–395. Available: https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/135/2/384-395.full.pdf.

Wisborg, K., Henriksen, T.B., Hedegaard, M., and Secher, N.J. (1996). Smoking during pregnancy and preterm birth. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 103(8), 800–805.

Yogman, M., Lavin, A., Cohen, G., and Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. (2018). The prenatal visit. Pediatrics, 142(1), e20181218. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-1218.

ZERO TO THREE. (n.d.). HealthySteps: Become a site. Available: https://www.healthysteps.org/become-a-site.

Zhang, G., Feenstra, B., Bacelis, J., Liu, X., Muglia, L.M., Juodakis, J., Miller, D.E., Litterman, N., Jiang, P.P., Russell, L., Hinds, D.A., Hu, Y., Weirauch, M.T., Chen, X., Chavan, A.R., Wagner, G.P., Pavlicev, M., Nnamani, M.C., Maziarz, J., Karjalainen, M.K., Rämet, M., Sengpiel, V., Geller, F., Boyd, H.A., Palotie, A., Momany, A., Bedell, B., Ryckman, K.K., Huusko, J.M., Forney, C.R., Kottyan, L.C., Hallman, M., Teramo, K., Nohr, E.A., Davey Smith, G., Melbye, M., Jacobsson, B., and Muglia, L.J. (2018). Genetic associations with gestational duration and spontaneous preterm birth. New England Journal of Medicine, 337, 1156–1167. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1612665.