6

Policy Strategies

As discussed in Chapter 2, the influences on mental, emotional, and behavioral (MEB) development include not only proximal factors that operate on individual children and families but also distal factors—characteristics of communities and society that shape opportunities and experiences. The intervention strategies discussed thus far address the promotion of MEB health and prevention of MEB problems directly, but other, more indirect strategies can promote well-being and alleviate sources of economic and other stress through policies with broad, population-level effects. We use the term policy to refer to actions taken by government entities at the community, state, or federal level to pursue social improvements; these actions may include formal rules, legislative actions, administrative programs, targeted funding initiatives, or other mechanisms.1 While much remains to be learned about how policies influence the environments in which MEB development occurs, increasing attention to the possibilities for using scientific evidence about the effects of policy on public health and other social objectives has strengthened the foundation for policy strategies (see, e.g., Brownson, 2011; Catalano et al., 2012; Rajabi, 2012; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016).

Policy can affect the full range of institutions and structures in neighborhoods, communities, and society, including families, schools, churches, health care systems, community organizations, businesses, and corporations. The resulting characteristics and actions of those institutions and structures in turn affect the physical, economic, and social environments experienced by children and their families in their communities. Thus, policy can influence the distribution of wealth; employment; and the health care, education, child welfare, and juvenile justice systems—all of which, as discussed in Chapter 2, have implications for MEB development and health.

___________________

1 The term policy is used interchangeably with the term law throughout this chapter. In its narrowest sense, law may refer only to formal rules passed by legislative bodies and implemented by executive branches, but the discussion here also includes regulatory actions by government agencies.

Policies also can be used as a public health tool to protect populations against risks and prevent disease or harm. For example, some policies provide guidelines that directly alter the environment, thereby influencing exposure to risks or protections. Public health gains have been achieved through such laws, including through the regulation of dangerous substances such as lead, air pollution, alcohol, and tobacco. Tax law and safety net programs have direct effects on family resources, as well as on the distribution of resources within a society. Policy can also support opportunities for positive parenting, education, and economic mobility, the effects of which may explain large differences in health outcomes by neighborhood (Chetty and Hendren, 2018; Komro et al., 2016).

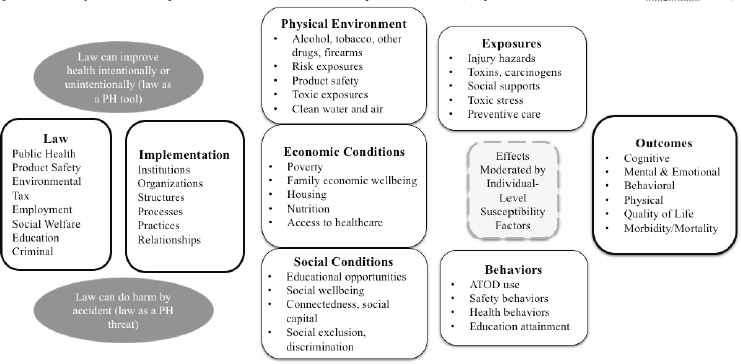

Figure 6-1 illustrates the processes through which laws influence child development and health, and highlights how the environments of children can be altered to reduce adverse exposures or increase protective factors (Komro, O’Mara, and Wagenaar, 2013). The figure demonstrates how the many dimensions of the environment drive exposures and behaviors that, when moderated by individual-level factors, ultimately affect population-level child outcomes (Komro, Flay, and Biglan, 2011).

This chapter looks at policies at all levels of government that can affect MEB development and health outcomes in children and youth in the areas of health care and nutrition, economic well-being, risk behavior and injury, and education.

SOURCE: Adapted from Komro, O’Mara, and Wagenaar (2013).

HEALTH CARE AND NUTRITION

A number of large-scale federal policies are designed to facilitate low-income families’ access to health care and adequate nutrition.

Health Care

Several federal programs are focused on access to and affordability of health care for children and adolescents. Other health care–related federal programs include the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) Program and the Mental Health Parity Act (MHPA).

Access to and Affordability of Health Care

One federal health care program that has had a substantial effect on the MEB health of children and youth is Medicaid, established by the Social Security Act of 1965. Medicaid provides health insurance to millions of low-income adults, children, pregnant women, and people with disabilities, and it is supplemented by the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). In 2016, these two programs provided coverage to 45 million children under the age of 18, 45 percent of U.S. children under 6, and 35 percent of those ages 6–18 (Chester and Burak, 2016).2 Medicaid is the single largest payer for mental health services in the United States (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, n.d.-a). Because the states and the federal government fund Medicaid jointly, states have considerable latitude in choosing which Medicaid benefits to provide.

The Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit is the specific component of Medicaid that targets child health. States are required to provide EPSDT services—including developmental and behavioral screening, vision services, dental services, and hearing services—for all children under age 21 enrolled in Medicaid. When a screening examination indicates a need for further evaluation, EPSDT provides diagnostic services. Additionally, EPSDT requires that necessary health care services be made available for the treatment of all physical and mental illnesses discovered during the screening and diagnostic processes (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, n.d.-b).

The 1997 passage of CHIP built on the Medicaid program to provide coverage to additional American children. As of 2017, 9.4 million children were enrolled in CHIP (David-Ferdon and Simon, 2014). Like Medicaid, CHIP is jointly funded by the states and the federal government. Notably, all CHIP programs cover physical, occupational, and speech and language therapies. CHIP also requires the developmental and behavioral screenings covered by EPSDT.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), enacted in 2010, extended Medicaid coverage to millions more American families. It also specified essential health benefits whose coverage was mandatory for all individual and small-group health plans. Mental health and substance use disorder services, including behavioral health treatment, are among these essential health benefits (Davies, Morriss, and Glazebrook, 2014).

___________________

2 See https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2016/12/13/fact-sheet-medicaids-role-for-youngchildren.

States’ flexibility in both Medicaid and CHIP program design results in differences in coverage that can lead to negative MEB health outcomes. Beginning in 2020, for example, states will have greater flexibility in choosing essential health benefits, which may result in reduced access to mental health services for Medicaid participants (de Kleijn et al., 2015). Additionally, while some states choose to reimburse providers for screening for maternal depression through the Medicaid program, most states do not. It should also be noted that in most states, neither Medicaid nor CHIP supports reimbursement of providers for MEB-related promotion and prevention programs, even though global access to such programs is associated with earlier pregnancy care, better birth outcomes, and early developmental screening.

Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) Program

The MIECHV Program was the first federal program to support large-scale promotion and prevention programs aimed at improving parenting practices and children’s MEB outcomes. A prevention component of the ACA, it serves as a national support mechanism for the provision of home visitation for mothers and children at risk for adverse MEB outcomes (De La Rue et al., 2016). While the program has been able to serve only a segment of all children with need for those services, it represents the first national-level attempt to expand complex, effective support programs for infants and young children at high risk for adverse MEB development. It is currently being studied, but no outcome data are yet available.

Mental Health Parity Act (MHPA)

The MHPA, passed in 1996, prevented large group health plans from imposing annual lifetime limits on mental health benefits that are less favorable than the limits imposed on medical or surgical benefits. The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 built on the MHPA by adding new protections, including the extension of parity requirements to substance use disorders. The result of this federal law has been a significant reduction in the number of health plans that impose limits on behavioral health treatment (Thalmayer et al., 2017), potentially benefiting children in families in which mental health disorders interfere with caretaking.

Nutrition

Federal programs focused on the growth and healthy development of young children include the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); and the National School Lunch Program (NSLP). Evidence suggests that these programs reduce food insecurity and improve nutrition in children, and that broadening eligibility for these programs would foster children’s healthy MEB development.

Special Supplemental Nutrition Program Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)

The WIC program provides federal grants to states for supplemental foods, health care referrals, and nutrition education for low-income pregnant, breastfeeding, and postpartum women, as well as for infants and children up to age 5 who are at nutritional risk. In 2017, more than 7 million participants benefited from the WIC program (Food and Nutrition Service, 2019).4 The WIC program is associated with small but significant increases in birthweight and increased intake of healthy food and nutrients among pregnant and postnatal women (Black et al., 2012). After reviewing 40 years of research on WIC, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities concluded that it is a “cost-effective investment that improves the nutrition and health of low-income families—leading to healthier infants, more nutritious diets, and better health care for children, and subsequently to higher academic achievement for students” (Carlson and Neuberger, 2017, p. 1).

In 2009, the WIC food package policy was revised to promote consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy products. This revision is associated with an increase in the availability of healthy foods and beverages in authorized WIC stores and improved dietary intake among WIC participants (Schultz, Byker Shanks, and Houghtaling, 2015).

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

SNAP is a federal program that provides food-purchasing assistance to eligible low-income individuals and families (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2018). In 2017, an estimated 42 million people benefited from SNAP (Nchako and Cai, 2018). According to a recent report, SNAP is the primary source of nutrition assistance for many low-income families. It reduces food insecurity among children, enables families to purchase healthier food, and is associated with improved child health and fewer low-weight births. Moreover, exposure to the program during early childhood is linked with improved health in adulthood (Carolson and Keith-Jennings, 2018).

At the same time, SNAP does not eliminate food insecurity. SNAP benefits are estimated to be 25 percent less than the average cost of a low-income meal, and do not cover the cost of a low-income meal in 99 percent of U.S. counties (Waxman, Gundersen, and Thompson, 2018). Evidence supports the importance of expanding SNAP benefits during the summer months, when children lack access to free and reduced-price lunches through school (Carolson and Keith-Jennings, 2018).

___________________

4 See https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/frequently-asked-questions-about-wic.

National School Lunch Program (NSLP)

The NSLP is a federally assisted meal program that provides nutritionally balanced free or reduced-price lunches to children in public and nonprofit private schools. Children may be eligible to participate in this program if their families also participate in SNAP, or based on their status as a homeless, migrant, runaway, or foster child. They can also qualify on the basis of household income and family size. In 2016, 30.4 million children participated in the NSLP (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2017).

Children receiving free or reduced-price NSLP lunches consume fewer empty calories and more fiber, milk, fruit, and vegetables relative to income-eligible nonparticipants. They also are more likely to have adequate average intakes of calcium, vitamin A, and zinc. In addition, the NSLP is associated with lower rates of food insecurity among households with children (Ralston and Coleman-Jensen, 2017).

ECONOMIC WELL-BEING

Poverty and the risk factors associated with it present challenges at every phase of MEB development.5 Thus, economic policies that promote livable wages and income supplementation may have broad effects on children’s MEB health. Policies aimed at reducing poverty, especially those affecting neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage, are an important foundation for fostering healthy MEB development. Such policies include minimum wage laws, paid family leave, and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). Other policies, such as child care subsidies and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), are also designed to alleviate family poverty.

Although research on the impact of housing, employment, and economic policies (e.g., policies on supplemental security income) on MEB outcomes for children and families is limited, some evidence demonstrates an association. For example, more than 5 million low-income households receive federal housing assistance through Housing Choice Vouchers, Section 8 Project-based Rental Assistance, and Public Housing (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2017a), and more than one-third of these are households with children (Fischer, 2016). The receipt of housing vouchers among families with children has resulted in reduced homelessness, crowding, housing instability, and family poverty (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2017a). It is also clear that supplemental security income policies have enabled many families with children with disabilities to rise above the federal poverty level (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015). More detailed evidence about the relationship between poverty and child well-being can be found in a recently released National

___________________

5 The discussion in this section includes findings gathered by Komro (2018) for a paper commissioned for this study, available for free download at https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25201.

Academies report on poverty (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019).

Minimum Wage Laws

The current federal minimum wage is $7.25 per hour, and it has not increased since 2009. However, states, cities, and counties can set a higher minimum wage for their communities, and there are documented benefits to doing so that relate to MEB development and health. Increases in the minimum wage are associated with reduced smoking during pregnancy and increased prenatal care (Komro et al., 2016). Moreover, a $1 increase in the minimum wage is associated with both a 9.6 percent decline in reports of neglect of children ages 0–12 (Raissian and Bullinger, 2017) and a decreased rate of teenage pregnancies (Bullinger, 2017). At the same time, some evidence suggests unintended negative effects of increasing the minimum wage, including increases in alcohol-related fatalities among youth and in binge drinking, especially among adolescent males (Adams, Blackburn, and Cotti, 2012; Hoke and Cotti, 2015).

Paid Family Leave

The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) of 1993 mandates that employers with 50 or more employees provide 12 weeks of job-protected leave for workers so they can manage their own illnesses, care for a newborn or newly adopted child, or care for an immediate family member with an illness or disability. This leave, however, does not have to be paid and covers only about 60 percent of workers (Greenfield and Klawetter, 2016). The unpaid nature of the FMLA creates access barriers that affect lower-income working parents disproportionately, as only an estimated 34 percent of working parents meet eligibility requirements and earn enough to afford taking unpaid leave (Joshi et al., 2014). Evidence at the state level shows that when leave is paid, leave taking among minority workers increases significantly compared with when leave is unpaid (Joshi et al., 2014).

Substantial evidence indicates that paid leave for families with a newborn is beneficial: it is associated with decreases in maternal depression, improvements in infant health, increases in breastfeeding, a higher likelihood of infant immunization and well-baby visits, and improvement in children’s cognitive outcomes (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016; Wilson-Simmons, Setty, and Smith, 2018). Additionally, longitudinal studies of 16 European and 18 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries found that the provision of paid maternity and parental leave was associated with reductions in neonatal, infant, and child mortality. These benefits increased as the length of leave increased, and no benefits were found for leave that was unpaid or did not provide job protection (Heymann, Earle, and McNeill, 2013). A natural experiment with parental leave in Norway also provided evidence about leave policies. In 1977, Norway changed its leave policy

from one similar to that of the United States—12 weeks of unpaid leave—and began to provide 18 weeks of paid leave. Research comparing outcomes for children of matched women before and after the policy change demonstrated better long-term outcomes for the children of mothers taking paid leave, including higher IQ, better academic achievement, and less teen pregnancy (Murray Horwitz et al., 2018).

Among 44 countries surveyed by the OECD in 2019, the United States was the only one in which women are not entitled to any amount of paid maternity leave not voluntarily provided by their employers; the average across those countries was 37 weeks (OECD, 2019). In recent years, several U.S. states, including California, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island, as well as the District of Columbia, have passed their own paid family leave legislation; similar laws will take effect in Washington and Massachusetts in January 2020 (National Partnership for Women & Families, 2018). Currently, however, only about half of U.S. working women receive any paid leave before or after childbirth through employer or state programs (Laughlin, 2011), even though a U.S.-based study of paid family leave showed a reduction in maternal and infant rehospitalizations and increases in maternal exercise and stress management among those who took paid leave versus those who took unpaid or no leave (Jou et al., 2018). A U.S.-based study of unpaid leave also showed that children of college-educated and married mothers who were most able to take advantage of unpaid leave had small increases in birthweight, decreases in the likelihood of a premature birth, and substantial decreases in infant mortality (Rossin, 2011). Thus, while paid leave may provide the opportunity for greater benefits in child development, unpaid leave does offer some benefit.

Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)

The EITC is a tax benefit for low- to moderate-income working people (Sawhill and Pulliam, 2019). In addition to the federal EITC, 29 states plus the District of Columbia have established their own EITCs, which build on the federal credit (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2017b). In 2016, the EITC lifted an estimated 5.8 million people, including 3 million children, out of poverty; it reduced the severity of poverty for an additional 18.7 million people, including 6.9 million children. Without the EITC, the number of poor children would have been more than 25 percent higher (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2018).

Furthermore, federal and state EITCs have been found to have a positive effect on families’ economic circumstances; increase participation in the labor force, particularly among single mothers; and improve educational outcomes among both mothers and children (Gassman-Pines and Hill, 2013; Sherman, DeBot, and Huang, 2016; Spencer and Komro, 2017). Expansions of the EITC are associated with decreases in maternal smoking, decreases in low birthweight, and increases in average birthweight, especially among those with greater socioeconomic risk and the greatest increase in EITC income (Hamad and Rehkopf, 2015; Hoynes, Miller, and Simon, 2015; Markowitz et al., 2017; Strully,

Rehkopf, and Xuan, 2010; Wicks-Lim and Arno, 2017). States with more generous EITCs see larger improvements in infant health outcomes over time (Markowitz et al., 2017). Among children ages 6–14, state EITCs have been associated with an increase in private health care coverage, a lower probability of being in fair or poor health, and a high probability of being in excellent health (Baughman and Duchovny, 2016).

EITCs also are linked to specific MEB outcomes. EITC payments and EITC-related higher income are associated with improved home environments and reduced problem behaviors (Hamad and Rehkopf, 2015). There is evidence as well of an association between EITCs and a reduction in mother-reported child neglect and child protective services involvement, particularly among low-income single mothers (Berger et al., 2017), as well as fewer hospital admissions for abusive head trauma in children under the age of 2 (Klevens et al., 2017).

Child Care Subsidies

Most public expenditures on child care subsidies are provided by the Child Care and Development Fund, which was created alongside welfare reform in 1996 and is supported as a block grant to states (Herbst and Tekin, 2016). Eligibility for child care subsidies is conditioned on fulfilling a state-defined work requirement, which typically includes paid employment or participation in a job training or education program (Herbst and Tekin, 2016).

Evidence is mixed for the benefits of child care subsidies in improving child well-being. Whereas such subsidies have been shown to increase maternal employment (Herbst and Tekin, 2016), some evidence indicates that children who receive subsidized child care in the year before kindergarten score lower on tests of cognitive ability and show more behavioral problems (Johnson and Ryan, 2015). These negative effects largely disappear by the time children finish 1st grade and may be the result of poor quality or intermittent availability of child care. Additionally, the presence of wait lists for access to subsidized child care is associated with an increase in maltreatment investigations (Klevens et al., 2015).

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)

Through the TANF program, states receive block grants from the federal government to design and implement programs intended to help needy families achieve self-sufficiency. To receive these block grants, states must require that mothers work to be eligible for TANF benefits once their child reaches a certain age, as established by the state. States in which mothers are required to return to work earlier in their child’s life show significantly higher rates of infant mortality among unmarried women with a high school education or less and at least one previous birth (Leonard and Mas, 2008). Early maternal employment also is associated with negative effects, including increased depressive symptoms and reduced rates of breastfeeding (Herbst, 2017).

TANF benefits have little demonstrated effect on child well-being (Dunifon, Hynes, and Peters, 2006; Wang, 2015), likely because the benefits are too small to lift families out of poverty (Wang, 2015). Indeed, strict lifetime limits on TANF benefits and tougher sanctions for noncompliance are related to higher levels of substantiated child maltreatment (Paxson and Waldfogel, 2003).

The degree to which TANF and the other programs discussed here influence the health and well-being of children is understudied. Future research that includes child health outcomes as a measure for program analysis would be a valuable contribution to the literature.

RISK BEHAVIOR AND INJURY

Policies designed to limit harmful behaviors and exposures and to prevent injuries have also benefited young people.

Limiting Harmful Behaviors and Exposures

Policies that discourage harmful behaviors or exposures—especially to alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, opioids, and lead—have pronounced benefits for preventing harm to children and promoting healthy MEB development. Children’s healthy MEB development can be fostered by policies that discourage substance use by parents and youth, and that protect fetuses and children from toxic exposures. There are several mechanisms through which this can be accomplished.

Alcohol

A number of policies have proven effective in reducing alcohol use and alcohol-related harms among youth. Raising the minimum legal drinking age to 21 has reduced both frequent and heavy drinking (DeJong and Blanchette, 2014; Hingson and White, 2014; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016; Wagenaar and Toomey, 2002). It is also associated with a reduced suicide rate among youth (Xuan et al., 2016), and has the potential to reduce preconception and prenatal alcohol use.

There is also evidence that policies making it illegal for those younger than age 21 to drive with any measureable blood alcohol concentration reduce both driving after drinking among youth and alcohol-related traffic deaths (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). Moreover, social host liability laws, which hold liable adults who host underage drinking parties on their property, are associated with declines in binge drinking, driving after drinking, and alcohol-related traffic deaths (Hingson and White, 2014; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). Requirements for signs warning against the risk of drinking during pregnancy are associated with a significant reduction in prenatal alcohol exposure, as well as decreases in very low-birthweight and very preterm births (Cil, 2017). Evidence also shows that increasing the price of

alcohol through taxation reduces alcohol-related harms among underage youth (Elder et al., 2010; Xu and Chaloupka, 2011). However, the effects of increased alcohol taxation on alcohol use by pregnant women have not been assessed.

Tobacco

Clear evidence demonstrates that increasing the price of cigarettes through taxation provides significant benefit in preventing young people from taking up smoking (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). Also beneficial in preventing or reducing smoking are mass media campaigns, comprehensive community programs, comprehensive statewide tobacco control programs, and laws restricting the sale of tobacco to minors (DiFranza, 2012). Evidence shows further that comprehensive smoke-free legislation is associated with reductions in preterm births and pediatric hospital admissions for respiratory tract infections and asthma, both of which pose risks for adverse MEB development (Faber et al., 2016, 2017).

There is also evidence that comprehensive bans on tobacco advertising, which prohibit all types of advertising or promotion designed to encourage tobacco use, can reduce tobacco consumption (Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, n.d.). However, restrictions in the United States permit some forms of marketing, and there is currently no evidence that such partial bans effectively reduce tobacco consumption (American Lung Association, 2019). International studies comparing the effects of restrictions on point-of-sale tobacco marketing have found reductions in exposure to marketing and impulse purchasing of cigarettes among adults (Li et al., 2013) and reductions in experimental and regular smoking among youth (Shang et al., 2015, 2016).

E-cigarettes, now the most commonly used tobacco products among youth, pose a public health concern (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). Little is known about legal and regulatory efforts to prevent initiation of use of these products among youth. One policy move has been the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) crackdown on the sale of e-cigarettes to minors and young people (Jenco, 2018), and this issue continues to be recognized as important. FDA recently proposed restricting sales of flavored e-cigarettes to closed-off areas of stores that are inaccessible to minors, as well as banning menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars (Kaplan and Hoffman, 2018), policies targeting youth users of tobacco products.

Marijuana

As of 2018, 30 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico had legalized the use of medical marijuana, while 8 states and the District of Columbia had legalized marijuana’s recreational use (Peeling, 2018; Smith, 2018). Few jurisdictions have legalized the use of medical marijuana for young people, and its use for recreational purposes has not been legalized at all for people under age 21 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016).

Studies have thus far found both benefits and risks associated with the legalization of marijuana. Consistent evidence indicates that states in which marijuana use is decriminalized have higher rates of unintentional exposure among children under age 6 (Wang et al., 2014). Other research has found that legalization of medical marijuana in states was followed by a decline in use of multiple drugs among 8th graders, no change in drug use among 10th graders, and increased cigarette and nonprescription opioid use among 12th graders. Legalization of recreational marijuana for people over age 21 was associated with increased rates of marijuana use among college students for those reporting recent heavy alcohol use (Kerr et al., 2017), but a decrease in marijuana use among all children under 18 (Dilley et al., 2019).

Studies have found no definitive evidence of an association between medical marijuana laws and traffic fatalities or youth suicide. Additional research in these areas could be useful. Also deserving attention is the potential of adverse effects on the MEB development of offspring of pregnant mothers who continue to use marijuana during their pregnancy (see Chapter 2).

Opioids

Current evidence on the value of policies aimed at restricting prescriptions for opioids is limited, but some work suggests that prescription drug monitoring programs may have a beneficial effect. Researchers have examined the effects of such programs, as well as policies to control the dispensing of narcotics not indicated medically. One study, for example, compared Georgia, where neither type of policy was in place, with Florida, which had both prescription drug monitoring and dispensing policies, and found that while Florida had modest reductions in dispensing of opioid prescriptions, there was no effect on length of treatment. The benefits were observed in patients and prescribers who were the heaviest users and dispensers (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). However, a nationwide study found mixed results for policies aimed at monitoring nonmedical use of prescription drugs and heroin, probably because these policies were varied in nature (Ali et al., 2017). Recent studies show some evidence that the strength of a monitoring program may be the most important variable (Bao et al., 2016; Pardo, 2017).

In the face of an increase in medically unnecessary opioid use among pregnant women, state lawmakers have increasingly responded with laws that criminalize this practice. Although limited research has been conducted, obstetricians and gynecologists have cautioned against such policies because they may prevent women from seeking prenatal care and other preventive health care services, as well as alienate vulnerable patients from their providers (Krans and Patrick, 2016; Kremer and Arora, 2015).

Lead

Since the 1970s, the United States has enacted several laws aimed at reducing blood lead levels in children. The first of these was the 1971 Lead-Based Paint Poisoning Prevention Act, which prohibited the use of lead paint in government-funded housing. Other federal efforts include the Environmental Protection Agency’s phase-out of lead in gasoline, limits on lead in residential paint and children’s products, the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act, and the prohibition against the use of lead pipes and plumbing (Komro, 2018). As a result of these policies, the average blood lead levels among children in the United States have declined about 94 percent, from 15 micrograms per deciliter in 1976 to 0.86 micrograms per deciliter today (Komro, 2018).

Ongoing management of children’s exposure to lead is critical, as any level of lead in children’s blood can have detrimental effects on their cognitive and behavioral development (Lanphear et al., 2005). If childhood lead exposure were completely eliminated, an estimated $84 billion in long-term benefits could be realized for each birth cohort. Children would be likely to have higher grade point averages, and more likely to earn high school diplomas and graduate from college. They would also be less likely to become teen parents or be convicted of crimes (Komro, 2018).

Injury Prevention

Policies to prevent injuries in young people address motor vehicles, bicycle helmets and concussion protocols, and firearms.

Motor Vehicles

The benefits of seatbelt and motor vehicle safety laws have been recognized for decades. Since the mid-1980s, all states have had some type of child restraint laws. However, state laws vary widely in the specificity of the population, restraint devices, vehicle operators, and penalties covered. Most state laws now include general seatbelt or restraint requirements and restraint based on height/weight definitions instead of age (Bae et al., 2014). Evaluations of state laws designed to increase use of booster seats have found increases in child restraint and correct restraint and reductions in traffic injury rates, injury hospital expenditures, and motor vehicle fatalities among covered children following the laws’ implementation (Eichelberger, Chouinard, and Jermakian, 2012; Farmer et al., 2009; Mannix et al., 2012; Pressley et al., 2009; Sun, Bauer, and Hardman, 2010).

States also have passed graduated driving licensing (GDL) laws in response to the increased risk of motor vehicle crashes among adolescents. GDL laws ideally include three stages: first requiring that an adult with a valid license be present at all times, second allowing the new driver to drive alone but with certain restrictions, and third providing full licensure to drive independently under the

usual laws and regulations. A systematic review found consistent evidence that GDL laws reduce crash and injury rates among young drivers, with stronger laws being associated with greater fatality reduction (Russell, Vandermeer, and Hartling, 2011).

Bicycle Helmets and Concussion Protocols

Growing evidence supports the effectiveness of laws and campaigns promoting the use of bicycle helmets. Studies have demonstrated an increase in helmet use following helmet legislation, especially among younger age groups and in those communities with low pre-intervention use (Karkhaneh et al., 2006; Macpherson and Spinks, 2008). This increased helmet use is also associated with a decrease in head injuries among children (Macpherson and Spinks, 2008).

Given increased attention to the long-term consequences of repeated traumatic brain injuries, all 50 states plus the District of Columbia have passed legislation requiring medical attention for head injuries among young athletes. These laws typically include concussion education, criteria for removal from play, requirements for evaluation, and requirements regarding return to play after concussion (Tomei et al., 2012). The laws focus on identifying and responding to traumatic brain injuries; no current state law focuses on primary prevention (Harvey, 2013). Whether these laws have resulted in the prevention of long-term MEB consequences of repeated concussions remains unknown.

Firearms

Consistent evidence shows that higher rates of U.S. household firearm ownership are associated with overall higher rates of gun suicide and homicide for every age group (Miller, Azrael, and Hemenway, 2002; National Research Council, 2004; Siegel and Rothman, 2016). Evidence also consistently suggests that waiting periods and background checks are associated with lower statewide suicide rates and decreased rates of firearm homicide (Anestis and Anestis, 2015; Lee et al., 2017). Age-specific laws, including those addressing child access prevention, which focus on safe storage and juvenile age restrictions, are associated with a decrease in suicide among adolescents (Parikh et al., 2017), in pediatric unintentional firearm injuries (Parikh et al., 2017), and in unintentional firearm deaths (Santaella-Tenorio et al., 2016).

EDUCATION

Laws and policies at the federal, state, and local levels affect schools and their ability to promote MEB health. Chapter 4 reviews MEB interventions delivered within schools; here we look briefly at education policies intended to influence young people’s behavior and welfare.

Zero Tolerance Policies

The zero tolerance philosophy became widespread in schools in the early 1990s as a method for requiring predetermined consequences for the actions of students. Although there is no singular definition of zero tolerance, it typically refers to punitive responses that are meant to be applied regardless of the gravity of the individual’s behavior or the situational context (American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force, 2008). The underlying assumption behind these policies is that they will deter other students from engaging in similar behavior, thus creating an improved school climate. Zero tolerance policies are often linked to exclusionary discipline, such as expulsion and out-of-school suspension.

Although zero tolerance policies have been widely criticized by teachers, parents, and students alike, they remain relatively popular in American schools. Research shows, however, a negative relationship between the use of school suspension and expulsion and school-wide academic achievement, even after controlling for such demographic factors as socioeconomic status (American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force, 2008). Evidence also demonstrates the potential for zero tolerance policies to have negative impacts on MEB health. Specifically, such policies may lead to increases in student alienation, anxiety, rejection, and breaking of healthy adult bonds. Additionally, rather than reducing the likelihood of classroom disruption, school suspension appears to predict higher future rates of misbehavior and suspension among those students who are suspended. In the long term, students experiencing suspension and expulsion have a moderately higher likelihood of dropping out of school and failing to graduate on time. Prevention interventions may be more effective than zero tolerance policies as a means of achieving school discipline (American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force, 2008).

One study offers corroboration with respect to the negative impact of school policies that prescribe suspension or expulsion for drug use (Evans-Whipp et al., 2015). A cross-national study of school policy showed that the likelihood of student marijuana use was higher in schools in which administrators reported using out-of-school suspension for drug-related violations of school policy, and students reported low policy enforcement. Student marijuana use was less likely where students reported receiving abstinence messages at school and where students violating school policy were counseled about the dangers of marijuana use.

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)

ESSA, signed into law in 2015, includes various provisions meant to ensure success for both students and schools. This federal policy gives states the opportunity to receive grant funding by submitting education plans that align with general U.S. Department of Education goals; states and local education authorities have considerable leeway to use the funding to meet their own goals. States may

identify their own accountability targets and plans for meeting them, but must use indicators of academic proficiency as well as measures of student and educator engagement, school climate and safety, and other elements of public schooling (Education Week, 2015). Other provisions address protections for disadvantaged and high-need students and offer support for evidence-based local interventions.

This act established social-emotional development as a priority for schools, and it makes several funding streams available for social-emotional learning. The authors of ESSA also identified 60 evidence-based interventions for promoting social-emotional learning that schools can implement across all grade levels. Many of these interventions have been validated with samples that consist mainly of students from low-income families or racial/ethnic minority groups (Grant et al., 2017).

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

IDEA guarantees a free appropriate public education to children with disabilities and ensures that they receive special education and related services. The law emphasizes the importance of improving educational results for children with disabilities to ensure that they can enjoy equality of opportunity, full participation, independent living, and economic self-sufficiency. Under IDEA, more than 6.9 million children with disabilities receive special education and related services designed to meet their individual needs. More than 62 percent of children with disabilities now spend at least 80 percent of their school day in a general classroom. Early intervention services are being provided to more than 340,000 infants and toddlers with disabilities (Conley, Durlak, and Kirsch, 2015). Individual Education Plans and 504 Plans provide for school accommodations for an array of health problems, including those in the behavioral health area, and enhance opportunities for these children to grow academically and socially.

State Policies on Social-Emotional Learning

Recognizing the growing evidence that efforts to teach social-emotional learning can be effective (as discussed in Chapter 4), many states have passed regulations or enacted statutes to encourage instruction in this area in schools, either as part of a health curriculum or as a stand-alone component. A policy scan by Child Trends, an independent nonprofit organization, showed that 15 states require some form of social-emotional learning or character education, and another 15 states recommend it (Gabriel et al., 2019). Curricula in nearly 40 states include requirements related to some type of social-emotional learning skills, such as emotional or mental health or healthy relationships; curricula in 11 states include requirements for trauma-informed care (attention to past trauma in addressing students’ problems). In short, social-emotional learning requirements are not yet universal, but attention in this area appears to be increasing.

SUMMARY

We have discussed policies most directly related to MEB development in children and youth, predominantly those that are national in effect. Other policy approaches are likely to be of benefit as well. For example, evidence supports the common-sense observation that large-scale incarceration of adult males in low-income neighborhoods has negative outcomes for families (Brookings Institute, 2014; Wiltz, 2017). Policy approaches in such areas warrant extensive further study because they address important social determinants of child health and wellbeing.

It is also important to note the great variation in the implementation and sustainability of federal, state, and local policies that directly affect the health and well-being of not only individual children and families but also entire neighborhoods and communities. Research on these issues has been limited with respect to the MEB development of children and adolescents. For example, state and local tobacco policies vary greatly by locale, and their influence is affected even by the density of tobacco outlets within neighborhoods and by the specific enforcement efforts of neighborhood police and health departments within communities. Also varying widely are local and state policies on assessment for eligibility, enrollment, and continuation reviews for the federal Supplemental Security Income program for children with disabilities. It is important to learn about the impact of these policy variations on children’s MEB development and health. In fact, if linked to rates of MEB problems in young people, this variation could make a positive contribution to understanding the effectiveness of these policies.

REFERENCES

Adams, S., Blackburn, M.L., and Cotti, C.D. (2012). Minimum wages and alcohol-related traffic fatalities among teens. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(3), 828–840.

Ali, M.M., Dowd, W.N., Classen, T., Mutter, R., and Novak, S.P. (2017). Prescription drug monitoring programs, nonmedical use of prescription drugs, and heroin use: Evidence from the national survey of drug use and health. Addictive Behaviors, 69, 65–77.

American Lung Association. (2019). Tobacco industry marketing. Available: https://www.lung.org/stop-smoking/smoking-facts/tobacco-industry-marketing.html.

American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force. (2008). Are zero tolerance policies effective in schools? An evidentiary review and recommendations. American Psychologist, 63(9), 852–862.

Anestis, M.D., and Anestis, J.C. (2015). Suicide rates and state laws regulating access and exposure to handguns. American Journal of Public Health, 105(10), 2049–2058.

Bae, J.Y., Anderson, E., Silver, D., and Macinko, J. (2014). Child passenger safety laws in the United States, 1978–2010: Policy diffusion in the absence of strong federal intervention. Social Science & Medicine, 100, 30–37.

Bao, Y., Pan, Y., Taylor, A., Radakrishnan, S., Luo, F., Pincus, H.A., and Schackman, B.R. (2016). Prescription drug monitoring programs are associated with sustained reductions in opioid prescribing by physicians. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 35(6), 1045–1051.

Baughman, R.A., and Duchovny, N. (2016). State earned income tax credits and the production of child health: Insurance coverage, utilization, and health status. National Tax Journal, 69(1), 103–132.

Berger, L.M., Font, S.A., Slack, K.S., and Waldfogel, J. (2017). Income and child maltreatment in unmarried families: Evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit. Review of Economics of the Household, 15(4), 1345–1372.

Black, A.P., Brimblecombe, J., Eyles, H., Morris, P., Vally, H., and O’dea, K. (2012). Food subsidy programs and the health and nutritional status of disadvantaged families in high income countries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 12, 1099.

Brookings Institute. (2014). The economic and social effects of crime and mass incarceration in the United States. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Brownson, R.C. (2011). Evidence-based public health. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bullinger, L.R. (2017). The effect of minimum wages on adolescent fertility: A nationwide analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 107(3), 447–452.

Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. (n.d.). Comprehensive advertising bans reduce tobacco use. Available: https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/global/pdfs/en/APS_tobacco_use.pdf.

Carlson, S., and Neuberger, Z. (2017). WIC works: Addressing the nutrition and health needs of low-income families for 40 years. Available: https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/wic-works-addressing-the-nutrition-and-health-needs-of-low-income-families.

Carolson, S., and Keith-Jennings, B. (2018). SNAP is linked with improved nutritional outcomes and lower health care costs. Available: https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-is-linked-with-improved-nutritional-outcomes-and-lower-health-care.

Catalano, R.F., Fagan, A.A., Gavin, L.E., Greenberg, M.T., Irwin, C.E., Jr., Ross, D.A., and Shek, D.T. (2012). Worldwide application of prevention science in adolescent health. The Lancet, 379(9826), 1653–1664.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2017a). Policy basics: Federal rental assistance. Available: https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/policy-basics-federal-rental-assistance.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2017b). Policy basics: State earned income tax credits. Available: https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/policy-basics-state-earned-income-tax-credits.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2018). The Earned Income Tax Credit. Washington, DC: Author.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Author. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99237.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (n.d.-a). Behavioral health services. Available: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/bhs/index.html.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (n.d.-b). Early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment. Available: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/epsdt/index.html.

Chester, A. and Burak, E.W. (2016). Fact sheet: Medicaid’s role for young children. Available: https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2016/12/13/fact-sheet-medicaids-role-for-young-children.

Chetty, R., and Hendren, N. (2018). The impacts of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility I: Childhood exposure effects. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(3), 1107–1162.

Cil, G. (2017). Effects of posted point-of-sale warnings on alcohol consumption during pregnancy and on birth outcomes. Journal of Health Economics, 53, 131–155.

Conley, C.S., Durlak, J.A., and Kirsch, A.C. (2015). A meta-analysis of universal mental health prevention programs for higher education students. Prevention Science, 16(4), 487–507.

David-Ferdon, C., and Simon, T. (2014). Preventing youth violence: Opportunities for action. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Davies, E.B., Morriss, R., and Glazebrook, C. (2014). Computer-delivered and web-based interventions to improve depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being of university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(5), e130.

de Kleijn, M.J., Farmer, M.M., Booth, M., Motala, A., Smith, A., Sherman, S., Assendelft, W.J., and Shekelle, P. (2015). Systematic review of school-based interventions to prevent smoking for girls. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 109. doi:10.1186/s13643-015-0082-7.

De La Rue, L., Polanin, J.R., Espelage, D.L., and Pigott, T.D. (2016). A meta-analysis of school-based interventions aimed to prevent or reduce violence in teen dating relationships. Review of Educational Research, 87(1), 7–34.

DeJong, W., and Blanchette, J. (2014). Case closed: Research evidence on the positive public health impact of the age 21 minimum legal drinking age in the United States. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(Suppl. 17), 108–115.

DiFranza, J.R. (2012). Which interventions against the sale of tobacco to minors can be expected to reduce smoking? Tobacco Control, 21(4), 436.

Dilley, J.A., Richardson, S.M., Kilmer, B., Pacula, R.L., Segawa, M.B., and Cerdá, M. (2019). Prevalence of cannabis use in youths after legalization in Washington state. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(2), 192–193. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4458.

Dunifon, R., Hynes, K., and Peters, E. (2006). Welfare reform and child wellbeing. Children and Youth Services Review, 28(11), 1273–1292.

Education Week. (2015). The Every Student Succeeds Act: Explained. Available: https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2015/12/07/the-every-studentsucceeds-act-explained.html?cmp=cpc-goog-ew-dynamic+ads&ccid= dynamic+ads&ccag=essa+explained+dynamic&cckw=&cccv=dynamic+a d&gclid=CjwKCAi.

Eichelberger, A.H., Chouinard, A.O., and Jermakian, J.S. (2012). Effects of booster seat laws on injury risk among children in crashes. Traffic Injury Prevention, 13(6), 631–639.

Elder, R.W., Lawrence, B., Ferguson, A., Naimi, T.S., Brewer, R.D., Chattopadhyay, S.K., Toomey, T.L., Fielding, J.E., and Task Force on Community Preventive Services. (2010). The effectiveness of tax policy interventions for reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38(2), 217–229.

Evans-Whipp, T.J., Plenty, S.M., Catalano, R.F., Herrenkohl, T.I., and Toumbourou, J.W. (2015). Longitudinal effects of school drug policies on student marijuana use in Washington state and Victoria, Australia. American Journal of Public Health, 105(5), 994–1000.

Faber, T., Been, J.V., Reiss, I.K., Mackenbach, J.P., and Sheikh, A. (2016). Smoke-free legislation and child health. NPJ Primary Care Respiratory Medicine, 26(1), 16067. doi:10.1038/npjpcrm.2016.67.

Faber, T., Kumar, A., Mackenbach, J.P., Millett, C., Basu, S., Sheikh, A., and Been, J.V. (2017). Effect of tobacco control policies on perinatal and child health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health, 2(9), e420–e437.

Farmer, P., Howard, A., Rothman, L., and Macpherson, A. (2009). Booster seat laws and child fatalities: A case-control study. Injury Prevention, 15(5), 348–350.

Fischer, W. (2016). Chart book: Rental assistance reduces hardship, promotes children’s long-term success. Available: https://www.cbpp.org/research/

housing/chart-book-rental-assistance-reduces-hardship-promotes-childrens-long-term-success.

Food and Nutrition Service. (2019). WIC frequently asked questions (FAQs). Available: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/frequently-asked-questions-about-wic.

Gabriel, A., Temkin, D., Steed, H., and Harper, K. (2019). State laws promoting social, emotional, and academic development leave room for improvement. Available: https://www.childtrends.org/state-laws-promoting-social-emotional-and-academic-development-leave-room-for-improvement.

Gassman-Pines, A., and Hill, Z. (2013). How social safety net programs affect family economic well-being, family functioning, and children’s development. Child Development Perspectives, 7(3), 172–181.

Grant, S., Hamilton, L., Wrabel, S., Gomez, C., Whitaker, A., Leschitz, J., Unlu, F., Chavez-Herrerias, E., Baker, G., Marrett, M., Harris, M., and Ramos, A. (2017). Social and emotional learning interventions under the Every Student Succeeds Act: Evidence review. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Greenfield, J.C., and Klawetter, S. (2016). Parental leave policy as a strategy to improve outcomes among premature infants. Health & Social Work, 41(1), 17–23.

Hamad, R., and Rehkopf, D.H. (2015). Poverty, pregnancy, and birth outcomes: A study of the earned income tax credit. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 29(5), 444–452.

Harvey, H.H. (2013). Reducing traumatic brain injuries in youth sports: Youth sports traumatic brain injury state laws, January 2009–December 2012. American Journal of Public Health, 103(7), 1249–1254.

Herbst, C.M. (2017). Are parental welfare work requirements good for disadvantaged children? Evidence from age-of-youngest-child exemptions. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 36(2), 327–357.

Herbst, C.M., and Tekin, E. (2016). The impact of child-care subsidies on child development: Evidence from geographic variation in the distance to social service agencies. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 35(1), 94–116.

Heymann, J., Earle, A., and McNeill, K. (2013). The impact of labor policies on the health of young children in the context of economic globalization. Annual Review of Public Health, 34(1), 355–372.

Hingson, R., and White, A. (2014). New research findings since the 2007 Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent and reduce underage drinking: A review. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(1), 158–169.

Hoke, O., and Cotti, C. (2015). Minimum wages and youth binge drinking. Empirical Economics, 51(1), 363–381.

Hoynes, H., Miller, D., and Simon, D. (2015). Income, the earned income tax credit, and infant health. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 7(1), 172–211.

Jenco, M. (2018). AAP: FDA crackdown on e-cigarette sales doesn’t go far enough. AAP News, September 13. Available: https://www.aappublications

.org/news/2018/09/13/ecigarettes091318.

Johnson, A.D., and Ryan, R.M. (2015). The role of child-care subsidies in the lives of low-income children. Child Development Perspectives, 9(4), 227–232.

Joshi, P.K., Geronimo, K., Romano, B., Earle, A., Rosenfeld, L., Hardy, E.F., and Acevedo-Garcia, D. (2014). Integrating racial/ethnic equity into policy assessments to improve child health. Health Affairs (Millwood), 33(12), 2222–2229.

Jou, J., Kozhimannil, K.B., Abraham, J.M., Blewett, L.A., and McGovern, P.M. (2018). Paid maternity leave in the United States: Associations with maternal and infant health. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 22(2), 216–225.

Kaplan, S., and Hoffman, J. (2018). F.D.A. Seeks restrictions on teens’ access to flavored e-cigarettes and a ban on menthol cigarettes. The New York Times, November 15. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/15/health/ecigarettes-fda-flavors-ban.html.

Karkhaneh, M., Kalenga, J.C., Hagel, B.E., and Rowe, B.H. (2006). Effectiveness of bicycle helmet legislation to increase helmet use: A systematic review. Injury Prevention, 12(2), 76–82.

Kerr, D.C.R., Bae, H., Phibbs, S., and Kern, A.C. (2017). Changes in undergraduates’ marijuana, heavy alcohol and cigarette use following legalization of recreational marijuana use in Oregon. Addiction, 112(11), 1992–2001.

Klevens, J., Barnett, S.B., Florence, C., and Moore, D. (2015). Exploring policies for the reduction of child physical abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 40, 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.013.

Klevens, J., Schmidt, B., Luo, F., Xu, L., Ports, K.A., and Lee, R.D. (2017). Effect of the Earned Income Tax Credit on hospital admissions for pediatric abusive head trauma, 1995–2013. Public Health Reports, 132(4), 505–511.

Komro, K.A. (2018). Laws influencing healthy mental, emotional, and behavioral development. Commissioned Paper for the Study on Fostering Healthy Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Development. Available: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25201 (under Resources tab).

Komro, K.A., Flay, B.R., and Biglan, A. (2011). Creating nurturing environments: A science-based framework for promoting child health and development within high-poverty neighborhoods. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(2), 111–134.

Komro, K.A., Livingston, M.D., Markowitz, S., and Wagenaar, A.C. (2016). The effect of an increased minimum wage on infant mortality and birth weight. American Journal of Public Health, 106(8), 1514–1516.

Komro, K.A., O’Mara, R.J., and Wagenaar, A.C. (2013). Understanding how law influences environments and behavior: Perspectives from public health. In A.C. Wagenaar and S. Burris (Eds.), Public health law research. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Krans, E.E., and Patrick, S.W. (2016). Opioid use disorder in pregnancy: Health policy and practice in the midst of an epidemic. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 128(1), 4–10.

Kremer, M.E., and Arora, K.S. (2015). Clinical, ethical, and legal considerations in pregnant women with opioid abuse. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 126(3), 474–478.

Lanphear, B.P., Hornung, R., Khoury, J., Yolton, K., Baghurst, P., Bellinger, D.C., Canfield, R.L., Dietrich, K.N., Bornschein, R., Greene, T., Rothenberg, S.J., Needleman, H.L., Schnaas, L., Wasserman, G., Graziano, J., and Roberts, R. (2005). Low-level environmental lead exposure and children’s intellectual function: An international pooled analysis. Environmental Health Perspectives, 113(7), 894–899.

Laughlin, L.L. (2011). Maternity leave and employment patterns of first-time mothers: 1961–2008. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau.

Lee, L.K., Fleegler, E.W., Farrell, C., Avakame, E., Srinivasan, S., Hemenway, D., and Monuteaux, M.C. (2017). Firearm laws and firearm homicides: A systematic review. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(1), 106–119.

Leonard, J., and Mas, A. (2008). Welfare reform, time limits, and infant health. Journal of Health Economics, 27(6), 1551–1566.

Li, L., Borland, R., Fong, G.T., Thrasher, J.F., Hammond, D., and Cummings, K.M. (2013). Impact of point-of-sale tobacco display bans: Findings from the international tobacco control four country survey. Health Education Research, 28(5), 898–910.

Macpherson, A., and Spinks, A. (2008). Bicycle helmet legislation for the uptake of helmet use and prevention of head injuries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2008(3), CD005401.

Mannix, R., Fleegler, E., Meehan, W.P., III, Schutzman, S.A., Hennelly, K., Nigrovic, L., and Lee, L.K. (2012). Booster seat laws and fatalities in children 4 to 7 years of age. Pediatrics, 130(6), 996–1002.

Markowitz, S., Komro, K.A., Livingston, M.D., Lenhart, O., and Wagenaar, A.C. (2017). Effects of state-level earned income tax credit laws in the U.S. on maternal health behaviors and infant health outcomes. Social Science & Medicine, 194, 67–75.

Miller, M., Azrael, D., and Hemenway, D. (2002). Rates of household firearm ownership and homicide across U.S. regions and states, 1988–1997. American Journal of Public Health, 92(12), 1988–1993.

Murray Horwitz, M.E., Molina, R.L., and Snowden, J.M. (2018). Postpartum care in the United States—New policies for a new paradigm. New England Journal of Medicine, 379(18), 1691–1693.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2015). Mental disorders and disabilities among low-income children. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/217800.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Parenting matters: Supporting parents of children ages 0–8. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/21868.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). A roadmap to reducing child poverty. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/25246.

National Partnership for Women & Families. (2018). State paid family and medical leave insurance laws. Washington, DC: Author.

National Research Council. (2004). Firearms and violence: A critical review. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/10881.

Nchako, C., and Cai, L. (2018). A closer look at who benefits from SNAP: State-by-state fact sheets. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). (2019). Key characteristics of parental leave systems. Available: http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF2_1_Parental_leave_systems.pdf.

Pardo, B. (2017). Do more robust prescription drug monitoring programs reduce prescription opioid overdose? Addiction, 112(10), 1773–1783.

Parikh, K., Silver, A., Patel, S.J., Iqbal, S.F., and Goyal, M. (2017). Pediatric firearm-related injuries in the United States. Hospital Pediatrics, 7(6), 303–312.

Paxson, C., and Waldfogel, J. (2003). Welfare reforms, family resources, and child maltreatment. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 22(1), 85–113.

Peeling, A. (2018). State marijuana laws interactive map. Available: https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/legal-and-compliance/state-andlocal-updates/pages/marijuana-laws-by-state.aspx.

Pressley, J.C., Trieu, L., Barlow, B., and Kendig, T. (2009). Motor vehicle occupant injury and related hospital expenditures in children aged 3 years to 8 years covered versus uncovered by booster seat legislation. Journal of Trauma, 67(1 Suppl.), S20–S29.

Raissian, K.M., and Bullinger, L.R. (2017). Money matters: Does the minimum wage affect child maltreatment rates? Children and Youth Services Review, 72, 60–70.

Rajabi, F. (2012). Evidence-informed health policy making: The role of policy brief. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 3(9), 596–598.

Ralston, K., and Coleman-Jensen, A. (2017). USDA’s national school lunch program reduces food insecurity. Available: https://www.ers.usda/gov/amber-waves/2017/august/usda-s-national-school-lunch-program-reduces-food-insecurity.

Rossin, M. (2011). The effects of maternity leave on children’s birth and infant health outcomes in the United States. Journal of Health Economics, 30(2), 221–239.

Russell, K.F., Vandermeer, B., and Hartling, L. (2011). Graduated driver licensing for reducing motor vehicle crashes among young drivers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (10), CD003300.

Santaella-Tenorio, J., Cerdá, M., Villaveces, A., and Galea, S. (2016). What do we know about the association between firearm legislation and firearm-related injuries? Epidemiologic Reviews, 38(1), 140–157.

Sawhill, I.V., and Pulliam, C. (2019). Lots of plans to boost tax credits: Which is best? Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Schultz, D.J., Byker Shanks, C., and Houghtaling, B. (2015). The impact of the 2009 Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children food package revisions on participants: A systematic review. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 115(11), 1832–1846.

Shang, C., Huang, J., Cheng, K.W., Li, Q., and Chaloupka, F.J. (2016). Global evidence on the association between POS advertising bans and youth smoking participation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(3), E306. doi:10.3390/ijerph13030306.

Shang, C., Huang, J., Li, Q., and Chaloupka, F.J. (2015). The association between point-of-sale advertising bans and youth experimental smoking: Findings from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS). AIMS Public Health, 2(4), 832–844.

Sherman, A., DeBot, B., and Huang, C.-C. (2016). Boosting low-income children’s opportunities to succeed through direct income support. Academic Pediatrics, 16(3), S90–S97.

Siegel, M., and Rothman, E.F. (2016). Firearm ownership and suicide rates among U.S. men and women, 1981–2013. American Journal of Public Health, 106(7), 1316–1322.

Smith, K.B. (2018). Governing states and localities + state and local government (6th edition). London, UK: CQ Press.

Spencer, R.A., and Komro, K.A. (2017). Family economic security policies and child and family health. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 20(1), 45–63.

Strully, K.W., Rehkopf, D.H., and Xuan, Z. (2010). Effects of prenatal poverty on infant health: State earned income tax credits and birth weight. American Sociological Review, 75(4), 534–562.

Sun, K., Bauer, M.J., and Hardman, S. (2010). Effects of upgraded child restraint law designed to increase booster seat use in New York. Pediatrics, 126(3), 484–489.

Thalmayer, A.G., Friedman, S.A., Azocar, F., Harwood, J.M., and Ettner, S.L. (2017). The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) evaluation study: Impact on quantitative treatment limits. Psychiatric Services, 68(5), 435–442.

Tomei, K.L., Doe, C., Prestigiacomo, C.J., and Gandhi, C.D. (2012). Comparative analysis of state-level concussion legislation and review of current practices in concussion. Neurosurgical Focus, 33(6), E11, 1–9. doi:10.3171/2012.9.FOCUS12280.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2017). The National School Lunch Program. Washington, DC: Author.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2018). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Available: https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health. Washington, DC: Author.

Wagenaar, A.C., and Toomey, T.L. (2002). Effects of minimum drinking age laws: Review and analyses of the literature from 1960 to 2000. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, (Suppl. 14), 206–225.

Wang, G.S., Roosevelt, G., Le Lait, M.C., Martinez, E.M., Bucher-Bartelson, B., Bronstein, A.C., and Heard, K. (2014). Association of unintentional pediatric exposures with decriminalization of marijuana in the United States. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 63(6), 684–689.

Wang, J.S.-H. (2015). TANF coverage, state TANF requirement stringencies, and child well-being. Children and Youth Services Review, 53, 121–129.

Waxman, E., Gundersen, C., and Thompson, M. (2018). How far do SNAP benefits fall short of covering the cost of a meal? Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Wicks-Lim, J., and Arno, P.S. (2017). Improving population health by reducing poverty: New York’s earned income tax credit. SSM—Population Health, 3, 373–381.

Wilson-Simmons, R., Setty, S., and Smith, T.T. (2018). Supporting America’s low-income working families through universal paid family leave. New York: National Center for Children in Poverty.

Wiltz, T. (2017). Locked up: Is case bail on the way out? Stateline, March 1. Available: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2017/03/01/locked-up-is-cash-bail-on-the-way-out.

Xu, X., and Chaloupka, F.J. (2011). The effects of prices on alcohol use and its consequences. Alcohol Research & Health, 34(2), 236–245.

Xuan, Z., Naimi, T.S., Kaplan, M.S., Bagge, C.L., Few, L.R., Maisto, S., Saitz, R., and Freeman, R. (2016). Alcohol policies and suicide: A review of the literature. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(10), 2043–2055.