10

Exploring Recent Progress

Before considering next steps for fostering mental, emotional, and behavioral (MEB) health in children and youth, it is important to reflect on what has been accomplished in the decade since the publication of the 2009 National Research Council and Institute of Medicine report (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009). This chapter first looks at a sampling of programs that have been implemented or expanded at the federal and state levels, as well as efforts of private foundations and growing interest on the part of U.S. businesses, to illustrate the progress that has been made. It then focuses on new opportunities for promotion of MEB health that have been created by advances in technology. The last part of the chapter considers challenges that remain.

A SAMPLING OF PROMISING EFFORTS

Since 2009, both federal and state resources have been expended on developing new interventions to improve MEB health in children and youth, as well as conducting rigorous evaluations, replicating proven interventions, and adapting and disseminating them in new contexts. Important initiatives have also been undertaken by private foundations and the business community.

Federal Initiatives

The federal government has many programs focused on the MEB health of children and youth, supported by several agencies. One of these agencies is the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. SAMHSA’s mission is fostering public health efforts to advance behavioral health, and the agency has many programs designed to advance that mission.1 SAMHSA and the other federal agencies with youth-related MEB health programs have emphasized the importance of building an evidence base for these programs (Interagency Working Group on Youth Programs, n.d.) and have provided funding for

___________________

replication, adaptation, innovation, and evaluation. In 2017, for example, the U.S. Department of Education launched the Education Innovation and Research (EIR) grant program, part of a larger effort called Investing in Innovation. EIR supports the development, implementation, and scaling of innovative and evidence-based programs in coordination with state and local efforts through grants to both new and ongoing projects. In funding new projects, it focuses on launching, iterating, and refining interventions that have the potential to be scaled up; the criteria for funding ongoing projects include rigorous evaluation that justifies replication and scaling (U.S. Department of Education, 2015).

Another federal program that includes a focus on building the evidence for interventions is the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) Program, discussed in Chapter 6. MIECHV, created by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, is designed to improve maternal and child health, prevent child abuse, encourage positive parenting, and promote child development and school readiness through home visits with pregnant women and parents of young children (Paulsell, Del Grosso, and Supplee, 2014). Grants are given to states, tribal organizations, and nonprofit organizations, and grantees choose from a list of evidence-based service delivery models (states are allowed to use up to 25 percent of that funding for other programs). Grantees are required to demonstrate measurable improvement in at least four of six focus areas:

- improvement in maternal and newborn health;

- reduction in child injuries, abuse, and neglect;

- improved school readiness and achievement;

- reduction in crime or domestic violence;

- improved family economic self-sufficiency; and

- improved coordination and referral for other community resources and supports.

In addition to providing funds for home visitation programs directly, MIECHV funds a research and development platform. In 2017, for example, MIECHV awarded The Johns Hopkins University $1.3 million for the development of a network of researchers and practitioners to increase knowledge about the implementation and effectiveness of home visitation programs (Health Resources and Services Administration, n.d.). Examples of additional federal initiatives aimed at fostering MEB health are listed in Table 10-1.

TABLE 10-1 Examples of Federal Initiatives to Foster MEB Health

| Initiative | Focus Area(s) | Funding Supports | Agency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Investing in Innovation Fund (i3) | Educational access, achievement, and completion |

|

U.S. Department of Education |

| Teen Pregnancy Prevention Initiative |

|

|

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

| Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program (MIECHV) |

|

|

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

| Social Innovation Fund (SIF) |

|

|

Corporation for National and Community Service |

| Trade Adjustment Assistance Community College and Career Training (TAACCCT) |

|

|

U.S. Departments of Labor and Education |

| Workforce Innovation Fund |

|

|

U.S. Departments of Labor, Education, and Health and Human Services |

| Permanency Innovations Initiative (PII) |

|

|

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

SOURCE: See https://youth.gov/evidence-innovation/investing-evidence.

Finally, it is important to note that while federal efforts to promote MEB health and prevent MEB disorders and to evaluate their results are expanding rapidly, there has been significantly less federal emphasis on including MEB outcomes in the evaluation of programs whose principal focus is poverty, nutrition, and related areas. Many such programs are, nonetheless, likely to have important MEB outcomes.

State and Local Initiatives

States and communities have increasingly focused on implementing and evaluating evidence-based interventions to promote MEB health in the past decade. These initiatives have been diverse and have been funded through varying mechanisms and sources. They do, however, share an emphasis on expanding the evidence base for promotion of MEB health and prevention of MEB disorders, and on using this evidence base to implement programs in communities more effectively. Several examples of such initiatives are described below.

California

In 2004, California voters approved Proposition 63—the Mental Health Services Act—which legislated a 1 percent tax on all California personal incomes over $1 million to support the delivery of accessible, effective, and culturally competent prevention and mental health services for children and adults in each of the state’s 58 counties (Felton, Cashin, and Brown, 2010). Twenty percent of these funds is allocated to Prevention and Early Intervention (PEI) programs, which aim to reduce risk for mental illness and provide early treatment for mental health problems so as to reduce negative consequences, such as out-of-home placement, involvement with the justice system, and school dropout. The remaining funds are directed to such programs as Assertive Community Treatment, outreach and engagement, information technology, education and training, and innovation. In one county, 33 evidence-based PEI interventions, such as Triple P (Positive Parenting Program), have been delivered to children and adolescents, with the majority of youth showing improvement in psychological distress (Ashwood et al., 2018).

California Proposition 64—the California Marijuana Legalization Initiative—included guidance on how the tax revenue collected from legal marijuana sales should be directed. The tax revenue is first used to cover costs of administering and enforcing the measure. Next it is distributed to drug research, treatment, and enforcement, including an initial $10 million, increasing by $10 million annually until 2022, for grants to local health departments and community-based nonprofits for initiatives including mental health and substance use disorder treatment (California Office of the Attorney General, 2015). Additional revenue will also be distributed to youth drug education, prevention, and treatment initiatives (California Office of the Attorney General, 2015). The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative has released

recommendations for how these grants can be used to promote family and community resilience (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, 2019).

Colorado

A portion of the money raised by Colorado’s taxes on legal marijuana is used for community-based substance abuse prevention and health promotion programs. During 2016–2017 and 2017–2018, more than $16.1 million of marijuana-related revenue was used to implement a model called Communities That Care (described in Chapter 8) in 48 communities across the state (Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, n.d.). The effectiveness of Communities That Care has been validated on multiple levels: randomized controlled trials have demonstrated significant and sustained effects; the program has been implemented successfully in numerous communities, with fidelity to core components; and those findings have been replicated in independent trials (Communities That Care, n.d.).

Massachusetts

In 2016, the Massachusetts State Legislature convened the Special Legislative Commission on Behavioral Health Promotion and Upstream Prevention to address behavioral health needs, including opiate addiction, in the state.2 Made up of 24 community leaders with expertise in behavioral health, prevention, public health, addiction, mental health, criminal justice, health policy, epidemiology, and environmental health, the commission was tasked with identifying “evidence-based practices, programs and systems to prevent behavioral health disorders and promote behavioral health across the commonwealth.” It identified as primary goals identifying what is working, securing funding for effective programs, and thereby reducing the rates of behavioral disorders (PromotePrevent, n.d.). The commission issued a report in 2018 outlining a plan for promoting MEB health and preventing MEB disorders, and offering recommendations focused on investment in addressing behavioral problems early in young children and adolescents by applying an integrated behavioral health approach and on building the infrastructure for prevention and promotion (Cantwell, 2018).

Ohio

Ohio’s Joint Study Committee on Drug Use Prevention Education was charged with collecting information about comprehensive prevention education

___________________

2 For more information, see https://www.promoteprevent.com.

and making recommendations for substance use prevention education and other efforts in the state. The commission was a multidisciplinary group that included law enforcement officials; elected officials; and experts representing public education, prevention policy, and nonprofit entities. Its report, released in 2018, offers recommendations for providing annual age-appropriate prevention education in grades K–12 in Ohio schools, identifies best practices, and includes an inventory of effective programs (Ohio Attorney General’s Office, 2018).

Oregon

The PAX Good Behavior Game, an evidence-based program that promotes self-regulation, social-emotional learning, and a positive educational environment, has been implemented in classrooms in several Oregon counties. Funders supporting the implementation of this program include the Oregon Youth Development Council, Coordinated Care Organizations (networks of Medicaid providers), local departments of public health, and other community groups. (See Chapter 4 for a more detailed discussion of the Good Behavior Game.)

Pennsylvania

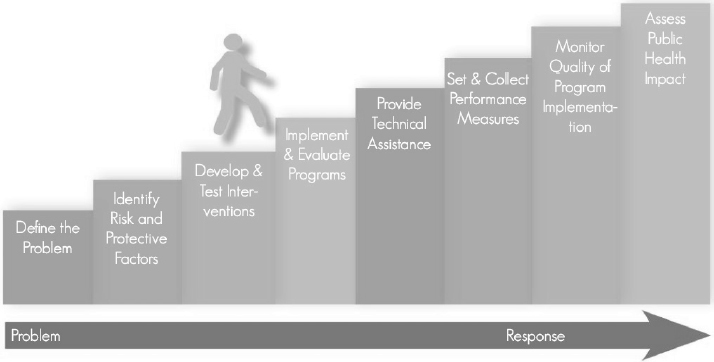

The Evidence-based Prevention and Intervention Support Center (EPISCenter) is supported by the Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs, the Department of Human Services, and the Commission on Crime and Delinquency, along with the Prevention Research Center at Penn State University. The focus of the EPISCenter is on implementing evidence-based programs in communities in order to promote youth development and reduce delinquency, violence, and substance use. To this end, the EPISCenter conducts original research and also provides assistance to communities for implementing and sustaining initiatives. The EPISCenter has developed an eight-step process for translating programs from the research laboratory into communities (see Figure 10-1). The first four steps represent the research activities that occur before programs are implemented in the field, while the last four steps are the translation and implementation activities that bring the programs to fruition in communities.

SOURCE: EPISCenter (2014).

Other State Initiatives

Like the federal government, states have a variety of policies that target other goals but can influence MEB outcomes for children and adolescents. For example, approximately 40 states, including the District of Columbia, now have universal preschool education as part of their public education systems, although eligibility, availability, and other characteristics of these programs vary (Rock, 2018). New York and California have increased minimum wage requirements. Early research suggests positive effects on workers and jobs, but effects on MEB outcomes for children and youth have not been evaluated. Efforts at the local and tribal level are also playing an important part (see, e.g., Chamberlain et al., 2016; Cwik et al., 2016).

Efforts of Private Foundations

Private foundations are also supporting efforts to build the research base and use it to implement initiatives that promote MEB health.

Evidence2Success

Evidence2Success, an initiative of The Annie E. Casey Foundation, is a framework for bringing public systems and community leaders together to improve children’s well-being (The Annie E. Casey Foundation, n.d.). The initiative provides a roadmap for efforts of cities and states to engage communities in implementing evidence-based programs and provides tools to facilitate the process. These tools include a survey with which to collect data on local youth and to highlight areas in which programs should focus their efforts, a blueprint that matches the communities’ strengths and needs with relevant evidence-based

programs, and public financing strategies to help generate or secure sustainable sources of funding for programs. Evidence2Success has been implemented in four sites.

Moving the Needle

Arnold Ventures (formerly the Laura and John Arnold Foundation) has established a number of programs designed to build the evidence base for social interventions and encourage policy makers to make decisions based on sound research and reliable evidence. One of these programs is Moving the Needle, a $15 million initiative announced in 2016. Its purpose is to provide funding for the implementation of effective social programs in order to make progress on problems including poverty, education, and crime. The policy team at Arnold Ventures performed a systematic review of programs and identified approximately a dozen that are supported by robust evidence. Government and nonprofit organizations can submit proposals for implementing these programs in their communities. Grantees must use existing resources (e.g., federal funding) to implement a program, with Arnold Ventures providing funds for technical assistance. All grantees must agree that their programs will participate in a randomized controlled trial whose results will be used to determine whether the effects found in previous studies can be replicated (Arnold Ventures, 2016).

The Pew-MacArthur Results First Initiative

The Pew-MacArthur Results First Initiative is a joint project of the Pew Charitable Trusts and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The program uses a cost–benefit analysis model that helps states identify which programs do and do not work; calculate potential returns on investment; rank programs based on costs, benefits, and risks; and predict the impact of different policy options. Results First supports this process with tools that help policy makers assess costs and benefits more accurately and formalize the use of data and evidence in decision making. In 2014, Results First released a report identifying and examining five key components of evidence-based policy making: program assessment, budget development, implementation oversight, outcome monitoring, and targeted evaluation (Pew-MacArthur Results First Initiative, 2014).

Role of the Business Community

Many U.S. businesses are devoting increased attention to ways in which they can have a positive impact on their employees’ health and well-being; on the local communities in which they are situated; and for larger entities, on such social goods as promoting the public health (Fuller and Raman, 2019; Gilbert, Houlahan, and Kassoy, 2015). This is a developing area, and relatively few such efforts address MEB health directly. However, companies are increasingly aware of the

financial benefits of addressing issues that affect employees and their families, such as reducing the costs of employee health care. Many business enterprises, large and small, have also recognized the importance of health, both physical and behavioral, for employees and their families; support for mental health is increasingly being acknowledged as an important component of comprehensive employee wellness programs, an approach that has demonstrated benefits (Osilla et al., 2012). Although such efforts seldom extend to consideration of child development outcomes and lifetime behavioral health for employees’ families, the health and well-being of communities has become a growing focus for many businesses and business groups, such as the Business Roundtable, a voluntary association of business leaders that includes promoting expanded opportunity for all in its mission.3

Many businesses also have significant resources to invest in their communities, and have begun to address their collective role in fostering better social and economic outcomes through targeted national initiatives, as well as through community support programs. Government policies, such as parental leave or minimum wage policies, can be used to encourage businesses to consider community and social issues, to provide businesses with resources and information, and to lead them to adopt family-supportive actions.

Research shows that employees with children who are physically and mentally healthy have fewer distractions and are able to be more productive in the workplace. By contrast, in many cases, employees whose children have chronic and disabling behavioral problems frequently find that either they or their spouse must quit their job to provide care and supervision for their child (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015). Given that 40 percent of the child population manifests a diagnosable behavioral disorder by age 25, this factor undoubtedly adds to employee turnover, a costly dimension of workforce maintenance (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009). Moreover, employees who have a child with a chronic health disorder are themselves at considerable risk for anxiety, depression, substance use, and other mental health disorders (Boat, Filigno, and Amin, 2017). These conditions have the potential to significantly undermine employee effectiveness.

Opportunities for business to directly support employee parents and improve the MEB development and health of their children include a number of evidence-based policies and practices. For example, paid maternity and paternity leave (see Chapter 6) have been shown to improve parent–child attachment and result in better child and family outcomes. When mothers do return to work, support for breastfeeding also encourages valued employees to stay on the job and eases their stress (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005, n.d.). Although such supports are becoming more common as more states adopt policies to encourage them, they are still inaccessible to many women. Similarly, child care that is stable and nurturing is of benefit for both children and their employee parents. Thus, the

___________________

3 For more information, see https://www.aspeninstitute.org/blog-posts/what-rolebusiness-society.

direct provision of child care or support for child care that is convenient and maximizes parent–child interaction also appears to contribute to positive child development outcomes (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018).

It is also worth noting that a healthy, thriving population can yield both strong employees and reliable customers. Poverty and unemployment are disturbingly prevalent in both urban and rural areas. Fully 40 percent of children in the United States grow up in households with incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty line (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015). Children who end up in prison, become addicted, or experience a lifetime of poverty will not benefit business interests. In short, because children’s MEB health is a significant factor in the status of both potential employees and consumers within a population, efforts to foster the healthy MEB development of children and youth can have an impact on business opportunities and growth. One obstacle to business engagement in this area is that children are not the major purchasers of products. Children’s wishes do, however, drive consumer decisions. The children of today will also be the purchasers of tomorrow, and their health outcomes will help to determine consumer resources and attitudes.

Business efforts to promote employee and community well-being are promising. While many of these efforts do not explicitly target MEB outcomes, they still promote healthy MEB development in children and youth indirectly. A few examples are highlighted in Box 10-1.

TECHNOLOGY-BASED DEVELOPMENTS

Many technological developments of the past decade have application to fostering MEB health. Interventions that use computer, mobile, gaming, and Internet technologies have a number of advantages: they can be delivered at low cost; are convenient; minimize staff burden; can deliver content while maintaining fidelity; and are appealing, particularly to adolescents. All of these advantages may make digital interventions easier to implement and sustain relative to traditional interventions.

Researchers have begun to explore the effectiveness of digital interventions in addressing MEB health among adults. For example, studies of their use with adults have suggested potential benefits in preventing the onset of major depressive episodes (Buntrock et al., 2014; Karyotaki et al., 2017). Initial reports are promising; for example, computerized cognitive-behavioral therapy produced a higher rate of recovery compared with standard face-to-face treatments. These results suggest that digital interventions may be viable alternatives to more traditional forms of intervention, with the potential advantage of substantially lower marginal costs (Coker et al., 2016).

There is also some evidence that Internet and mobile interventions can be used effectively with young people. The fields of eHealth (the provision of health services supported by electronic processes and communication) and mHealth (the provision of health services supported by mobile devices) have developed and grown because technology is ubiquitous, particularly among youth; encourages

active engagement; allows for a flexible and personalized environment; and is a primary means by which many adolescents obtain information and communicate (Lenhart, 2012). Adolescents’ heavy use of technology can make it a motivating medium for health services targeting this population. In 2013, for example, 77 percent of youth ages 12–19 owned a cell phone, and a significant majority were texting daily. Notably, those living in lower-income households are just as likely as their better-resourced peers—and in some cases more so—to use their cell phones to access the Internet (Madden et al., 2013).

The evidence for technology-based interventions for promotion of MEB health in youth is still emerging, but initial results suggest that such interventions are promising. For example, a systematic review showed the feasibility of using text messaging and apps to promote such behaviors as clinic attendance, contraceptive use, physical activity and weight management, human papillomavirus vaccination, smoking cessation, and sexual health behaviors among adolescents (Badawy and Kuhns, 2017). Approximately half of the studies reviewed demonstrated significant improvement in these behaviors. Other studies have shown the efficacy of technology-based approaches targeting MEB disorders including depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, self-harm, conduct disorder, eating disorders and body image issues, schizophrenia, psychosis, and insomnia, as well as suicide prevention (Ali et al., 2015; Huguet et al., 2018; Marsch and Borodovsky, 2016; Perry et al., 2016; Vigerland et al., 2016).

Other forms of technology show promise as well. For example, a recent meta-analysis of web-based interventions to address depression in adolescents and young adults found the interventions to be efficacious in the short term and to have a positive impact on symptoms of depression and anxiety in adolescents developing or diagnosed with those disorders (Pennant et al., 2015; Välimäki et al., 2017). Another meta-analysis covering Internet-based depression treatment for both adolescents and adults in nonclinical settings showed such treatment to be as effective as other forms of behavioral therapy and more effective than comparison conditions, such as physical activity and psychoeducation (Huguet et al., 2018). Other work has supported these findings, and has indicated that technology-based approaches for providing peer-to-peer support and suicide prevention services show promise (Ali et al., 2015; Perry et al., 2016; Vigerland et al., 2016). Early findings also suggest that therapeutic video games have potential in engaging adolescents with anxiety and reducing clinically measurable symptoms of that disorder; technology-based programs have been used to target substance use as well (Champion et al., 2013; Marsch and Borodovsky, 2016).

Overall, these results suggest that technology is a promising tool for promoting healthy MEB development, and its potential for delivering interventions at significantly lower cost relative to other approaches is reason to actively investigate its use. However, there are limitations to consider as well. For one, attrition is a major issue with digital interventions. Only a small proportion of users actually complete most digital interventions, although advocates for such interventions point out that the absolute numbers of users who complete the interventions are large given the interventions’ wide reach (Hardesty, 2012).

Another potential limitation is the fact that digital interventions have most frequently been tested with well-educated, highly motivated adults. The interventions tested may be less effective in real-world settings, where people may lack access to Internet-enabled devices or the knowledge or motivation to use the Internet.

On the other hand, digital interventions have the capacity to address disparities and bring health care to difficult-to-reach populations. For example, digital technologies have been used to address health issues in communities affected by war and other disasters (Knaevelsrud et al., 2015; Ruzek and Yeager, 2017; Ruzek et al., 2016), and to reach rural Latinos (Chavira et al., 2017) and Latinos nationally (Muroff et al., 2017; Pratap et al., 2017), as well as international populations of young people (Barrera, Wickham, and Munoz, 2015). They have also demonstrated success in delivering well-child care to low-income urban populations (Coker et al., 2016; Mimila et al., 2017). The use of technologies that can reach large numbers of individuals is especially attractive given the relative lack of health care resources in many diverse communities, including a dearth of providers who speak languages other than English in the United States. These technologies may therefore help reduce health disparities (Muñoz, 2010). This is an important consideration given research indicating not only that individuals with fewer resources have less access to health care interventions, but also that even when provided access to such interventions, they may benefit less from them relative to those with more resources.

At the same time, it is important to examine empirically whether certain segments of the population are less likely to benefit from technology-based interventions. For example, higher socioeconomic status at the country and individual levels was found to be associated with greater abstinence levels in an online smoking intervention study conducted in Spanish and English (Bravin et al., 2015). An additional concern associated with digital interventions is the possibility that third-party payers could use the evidence that digital tools are effective in preventing and treating MEB disorders to restrict reimbursement for in-person health care. Thus, it is essential to take into account the substantial impact of poverty on health status and on responsiveness to health interventions discussed in other parts of this report in decision making about the use of new intervention modes to reach greater proportions of all individuals with need.

ONGOING CHALLENGES

The programs discussed above highlight progress that has been made. We close by illustrating some of the questions that arise in the scaling up of programs that have demonstrable beneficial effects on children’s MEB development.

Trade-offs

The Nurse–Family Partnership (NFP) National Service Office is a national network of nurses who visit the homes of young pregnant women and

continue those visits through the children’s second birthday.4 This 40-year-old program has been the subject of three randomized controlled trials examining its effects on maternal and child health and child development, as well as numerous other evaluations and studies (Nurse–Family Partnership, 2017, 2018b). It has been disseminated to nearly all U.S. states, along with Canada and several European countries. The NFP website lists more than 34,000 families enrolled in 594 U.S. counties (Nurse–Family Partnership, 2018a). This is an impressive number, but it falls far short of population needs, considering that more than 20 percent of U.S. children live in families whose income falls below the federal poverty level (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015). Of those families eligible for home visitation programs, approximately half decline to enroll, and many of those who decline are identified as most in need (Goyal et al., 2014). Moreover, many participants do not remain engaged for the duration of home visitation programs (Holland et al., 2018).

As with many programs that progress to broad dissemination, this program’s effect sizes diminish with replication, even when the program is delivered with fidelity (Miller, 2015). Scaled-up delivery of NFP costs about $4,500 per child for each of the 2 years. An important challenge for implementation science and practice will be determining the extent to which cost, program complexity, and the infrastructure required for effective implementation will limit or permit rapid, broader dissemination of this and similar programs.

Home visiting programs, including NFP, served 156,000 families across the United States in 2017, reaching some families in 22 percent of rural and 36 percent of urban communities; these results were achieved with $1.5 billion appropriated through the Affordable Care Act over 5 years (Health Resources and Services Administration, n.d.). At this funding level, it appears that only a small percentage of the more than 5 million children ages 0–3 living in homes eligible for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program are reached (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015).

Reach Out and Read, a universal, low-cost early childhood and family intervention, is widely available and accepted by families of infants and young children through their primary health care well-child visits. This program aims to improve children’s communication skills and school readiness by encouraging daily time for story reading from the earliest months of life. Documented outcomes include improved receptive language, earlier reading, expanded vocabulary, and better school readiness, all of which are potential contributors to school success, which is a well-known resilience factor. There is evidence for sustained positive effects of this program through age 14 (Gilkerson et al., 2018; Thakur et al., 2016). Studies also document enhanced parent–child engagement and a reduction in maternal depression (Kumar et al., 2016). Home reading activates brain areas supporting brain imagery and narrative comprehension (Hutton et al., 2015). There is also evidence that this relatively low-cost program can boost an array of other factors in academic success and resilience factors,

___________________

4 For more information, see https://www.nursefamilypartnership.org.

including IQ and early language and reading skills, and may improve children’s social-emotional development as well (Mendelsohn et al., 2018).

The program is guided by a nonprofit organization, which in 2016 reported a budget of $12 million. It distributed books to 4.7 million families, is embedded in 6,080 health care sites in all 50 states (particularly in practice sites that serve low-resourced families), and has an annual cost of $20 per family served (Reach Out and Read, n.d.).

Positive Behavioral Intervention and Support is a school-based strategy for promoting prosocial behavior using behavioral rules and systems of reward for appropriate social behavior. This program has shown benefit in improving both academic and social behavior (Bradshaw, Mitchell, and Leaf, 2010; Horner et al., 2009). It has been implemented in 21,000 schools and reached 10,500,000 students (Sugai, Horner, and McIntosh, 2016). This is but one of a number of school-based universal interventions (in addition to the Good Behavior Game) that have been disseminated in school settings to reach large numbers of children at a low cost.

The above programs reflect very different approaches to improving MEB development. One choice is to implement high-cost, relatively complex programs whose positive impact on MEB development has been demonstrated using rigorous research methodology, but whose reach thus far has been limited. An option at the other extreme is to invest in programs that are less complex, intensive, and costly but have been widely disseminated in venues where infrastructure is already in place. These approaches may have a smaller impact on MEB outcomes for each individual child and family but affect a greater number of children overall. These choices represent trade-offs that need to be understood and factored into the selection of interventions; the same is true of policies that may improve MEB health.

Additional research will help in determining whether one approach has greater benefits or confirm that each has merit for different objectives. Being able to quantify and compare the impacts of programs based on both effectiveness and reach will be important for future program dissemination efforts. It is also important to note that this description of the dissemination of evidence-based interventions is necessarily incomplete. There is no registry of the implementation and reach of such interventions, let alone evidence on the degree to which implementation is sustained or beneficial outcomes are achieved. Such a registry is needed. A growing repository of data on the reach of interventions would make it easier to assess the fit of a particular approach, which is key to effective implementation and sustainability, as discussed in Part III of this report. Such a data repository would also support analysis of correlations among such factors as geography (cities, states, or regions) and measures of MEB and physical disorders among young people.

Financing

Many of the inner-city neighborhoods challenged by multigenerational poverty were created through structural racism in employment and housing policies, most notably the redlining of African American neighborhoods by the Federal Housing Authorities from the 1930s to 1970 and subsequent redlining by commercial banks, veterans’ programs, and other employment programs (Sampson and Wilson, 2013). City services and investment were removed from minority communities, and assets were allowed to decline over decades (Reece et al., 2015). Cleveland, Ohio, is representative of northern cities in which a small number of redlined communities resulting from policies enacted in the middle of the 20th century now account for a three-fold increase in black infant mortality, a six-fold increase in gun deaths, and a three-fold increase in school dropout compared with city averages. No single risk factor other than residence in one of these neighborhoods accounts for these changes (Reece et al., 2015).

Mental health promotion and prevention activities for children and adolescents, some two-generation community development approaches, and school-based interventions are among the approaches that can support the populations affected by these stark circumstances. Communities That Care and the Good Behavior Game, discussed in Chapters 8 and 4, respectively, are two well-regarded examples. Yet lack of consistent funding in many low-resource communities has limited their access to such programs (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015).

Traditional sources of funding are inadequate for health promotion and prevention for a variety of reasons (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019). For example, health insurance and health care resources are directed almost exclusively to treatment rather than promotion or prevention, despite evidence of their benefits. Indeed, community-delivered services that are classroom- or home-based are usually excluded from health insurance reimbursement. Philanthropic funding for such programs has been fragmented and insufficient and has not been consistently available to these neighborhoods. Moreover, available funding and programs too often are not coordinated in the service of carefully articulated goals; even Medicaid policies vary from state to state. Box 10-2 describes several innovative financing solutions with the potential to generate sustainable and effective support for community-based prevention programs.

REFERENCES

Ali, K., Farrer, L., Gulliver, A., and Griffiths, K.M. (2015). Online peer-to-peer support for young people with mental health problems: A systematic review. JMIR Mental Health, 2(2), e19.

The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (n.d.). Evidence2success. Available: https://www.aecf.org/work/evidence-based-practice/evidence2success.

Arnold Ventures. (2016). Arnold Foundation launches $15m competition to use evidence-based programs to “move the needle’” on social problems. Newsroom, April 22. Available: https://www.arnoldventures.org/newsroom/laura-john-arnold-foundation-launches-15-million-competition-useevidence-based-programs-move-needle-major-social-problems.

Arthur W. Page Center. (2019). Conscious capitalism: A definition. Available: https://pagecentertraining.psu.edu/public-relations-ethics/corporate-social-responsibility/lesson-2-introduction-to-conscious-capitalism/conscious-capitalism-a-definition.

Ashwood, J.S., Kataoka, S.H., Eberhart, N.K., Bromley, E., Zima, B.T., Baseman, L., Marti, F.A., Kofner, A., Tang, L., Azhar, G., Chamberlin, M., Erickson, B., Choi, K., Zhang, L., Miranda, J., and Burnam, M.A. (2018). Evaluation of the Mental Health Services Act in Los Angeles County: Implementation and outcomes for key programs. Rand Health Quarterly, 8(1), 2.

B Lab. (n.d.). Certified b corporation. Available: https://bcorporation.net.

Badawy, S.M., and Kuhns, L.M. (2017). Texting and mobile phone app interventions for improving adherence to preventive behavior in adolescents: A systematic review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 5(4), e50.

Barnes, A., Woulfe, J., and Worsham, M. (2017). A legislative guide to benefit corporations: Create jobs, drive social impact, and promote the economic health of your state. Available: http://benefitcompanybar.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Legislative-Guide-B-Corps_Final.pdf.

Barrera, A.Z., Wickham, R.E., and Munoz, R.F. (2015). Online prevention of postpartum depression for Spanish- and English-speaking pregnant women: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Internet Interventions, 2(3), 257–265.

Boat, T.F., Filigno, S., and Amin, R.S. (2017). Wellness for families of children with chronic health disorders. JAMA Pediatrics, 171(9), 825–826.

Bradshaw, C.P., Mitchell, M.M., and Leaf, P.J. (2010). Examining the effects of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on student outcomes: Results from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 12(3), 133–148.

Bravin, J.I., Bunge, E.L., Evare, B., Wickham, R.E., Pérez-Stable, E.J., and Muñoz, R.F. (2015). Socioeconomic predictors of smoking cessation in a worldwide online smoking cessation trial. Internet Interventions, 2(4), 410–418.

Buntrock, C., Ebert, D.D., Lehr, D., Cuijpers, P., Riper, H., Smit, F., and Berking, M. (2014). Evaluating the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of web-based indicated prevention of major depression: Design of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 25.

California Office of the Attorney General. (2015). Control, Regulate and Tax Adult Use of Marijuana Act, no. 15-0103.

Cantwell, J.M. (2018). Special commission on behavioral health promotion and upstream prevention. Available: https://www.promoteprevent.com.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2005). Support for breastfeeding in the workplace. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/pdf/BF_guide_2.pdf.

Chamberlain, P., Feldman, S.W., Wulczyn, F., Saldana, L., and Forgatch, M. (2016). Implementation and evaluation of linked parenting models in a large urban child welfare system. Child Abuse & Neglect, 53, 27–39.

Champion, K.E., Newton, N.C., Barrett, E.L., and Teesson, M. (2013). A systematic review of school-based alcohol and other drug prevention programs facilitated by computers or the internet. Drug and Alcohol Review, 32(2), 115–123.

Chavira, D.A., Bustos, C.E., Garcia, M.S., Ng, B., and Camacho, A. (2017). Delivering CBT to rural Latino children with anxiety disorders: A qualitative study. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(1), 53–61.

Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. (2019). Recommendations roadmap for California Proposition 64 expenditures: Advancing healing-centered and trauma-informed approaches to promote individual, family, and community resilience. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Coker, T.R., Chacon, S., Elliott, M.N., Bruno, Y., Chavis, T., Biely, C., Bethell, C.D., Contreras, S., Mimila, N.A., Mercado, J., and Chung, P.J. (2016). A parent coach model for well-child care among low-income children: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20153013.

Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. (n.d.). Youth substance abuse prevention: Communities That Care. Available: https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/cdphe/ctc.

Communities That Care. (n.d.). Research & results. Available: https://www.communitiesthatcare.net/research-results.

Conscious Capitalism San Diego. (n.d.). Conscious Capitalism movement. Available: https://ccsandiego.org/conscious-capitalism-movement.

Cwik, M.F., Tingey, L., Maschino, A., Goklish, N., Larzelere-Hinton, F., Walkup, J., and Barlow, A. (2016). Decreases in suicide deaths and attempts linked to the White Mountain Apache Suicide Surveillance and Prevention System, 2001–2012. American Journal of Public Health, 106(12), 2183–2189.

EPISCenter. (2014). EPISCenter 2014 Annual report. University Park, PA: Penn State University Report. Available: http://www.episcenter.psu.edu/sites/default/files/outreach/EPISCenter-Annual-Report-2014.pdf.

Felton, M.C., Cashin, C.E., and Brown, T.T. (2010). What does it take? California county funding requests for recovery-oriented full service partnerships under the Mental Health Services Act. Community Mental Health Journal, 46(5), 441–451.

Fuller, J.B., and Raman, M. (2019). The caring company: How employers can help employees manage their caregiving responsibilities—while reducing costs and increasing productivity. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School. Available: https://www.hbs.edu/managing-the-future-of-work/Documents/The_Caring_Company.pdf.

Gilbert, J., Houlahan, B., and Kassoy, A. (2015). What is the role of business in society? Available: https://www.aspeninstitute.org/blog-posts/what-role-business-society.

Gilkerson, J., Richards, J.A., Warren, S.F., Oller, D.K., Russo, R., and Vohr, B. (2018). Language experience in the second year of life and language outcomes in late childhood. Pediatrics, 142(4), e20174276.

Goyal, N.K., Hall, E.S., Jones, D.E., Meinzen-Derr, J.K., Short, J.A., Ammerman, R.T., and Van Ginkel, J.B. (2014). Association of maternal and community factors with enrollment in home visiting among at-risk, first-time mothers. American Journal of Public Health, 104(Suppl. 1), S144–S151.

Hardesty, L. (2012). Lessons learned from MITx’s prototype course. MIT News, July 16. Available: http://news.mit.edu/2012/mitx-edx-first-course-recap-0716.

Health Resources and Services Administration. (n.d.). Home visiting. Available: https://mchb.hrsa.gov/maternal-child-health-initiatives/home-visiting-overview.

Holland, M.L., Olds, D.L., Dozier, A.M., and Kitzman, H.J. (2018). Visit attendance patterns in nurse–family partnership community sites. Prevention Science, 19(4), 516–527.

Horner, R.H., Sugai, G., Smolkowski, K., Eber, L., Nakasato, J., Todd, A.W., and Esperanza, J. (2009). A randomized, wait-list controlled effectiveness trial assessing school-wide positive behavior support in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 11(3), 133–144.

Huguet, A., Miller, A., Kisely, S., Rao, S., Saadat, N., and McGrath, P.J. (2018). A systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy of Internet-delivered behavioral activation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 235, 27–38.

Hutton, J.S., Horowitz-Kraus, T., Mendelsohn, A.L., DeWitt, T., and Holland, S.K. (2015). Home reading environment and brain activation in preschool children listening to stories. Pediatrics, 136(3), 466–478.

Interagency Working Group on Youth Programs. (n.d.). Investing in evidence. Available: https://youth.gov/evidence-innovation/investing-evidence.

Karyotaki, E., Riper, H., Twisk, J., Hoogendoorn, A., Kleiboer, A., Mira, A., MacKinnon, A., Meyer, B., Botella, C., Littlewood, E., Andersson, G., Christensen, H., Klein, J.P., Schroder, J., Bretón-López, J., Scheider, J., Griffiths, K., Farrer, L., Huibers, M.J.H., Phillips, R., Gilbody, S., Moritz, S., Berger, T., Pop, V., Spek, V., and Cuijpers, P. (2017). Efficacy of self-guided Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in treatment of depressive symptoms: An individual participant data meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(4), 351–359. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0044.

Kelleher, K.J., Cooper, J., Deans, K., Carr, P., Brilli, R.J., Allen, S., and Gardner, W. (2015). Cost saving and quality of care in a pediatric accountable care organization. Pediatrics, 135(3), e582–e589.

Knaevelsrud, C., Brand, J., Lange, A., Ruwaard, J., and Wagner, B. (2015). Web-based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in war-traumatized Arab patients: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(3), e71.

Kumar, M.M., Cowan, H.R., Erdman, L., Kaufman, M., and Hick, K.M. (2016). Reach out and read is feasible and effective for adolescent mothers: A pilot study. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20(3), 630–638.

Lenhart, A. (2012). Teens, smartphones & texting. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Mackey, J., and Sisodia, R. (2014). Conscious capitalism: Liberating the heroic spirit of business. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

Madden, M., Lenhart, A., Duggan, M., Cortesi, S., and Gasser, U. (2013). Teens and technology 2013. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Makni, N., Rothenburger, A., and Kelleher, K. (2015). Survey of twelve children’s hospital-based accountable care organizations. Journal of Hospital Administration, 4(2), 64–73.

Marsch, L.A., and Borodovsky, J.T. (2016). Technology-based interventions for preventing and treating substance use among youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 25(4), 755–768.

Mendelsohn, A.L., Cates, C.B., Weisleder, A., Berkule Johnson, S., Seery, A.M., Canfield, C.F., Huberman, H.S., and Dreyer, B.P. (2018). Reading aloud, play, and social-emotional development. Pediatrics, 141(5), e201733393.

Miller, T.R. (2015). Projected outcomes of Nurse–Family Partnership home visitation during 1996–2013, USA. Prevention Science, 16(6), 765–777.

Mimila, M.A., Chung, P.J., Elliott, M.N., Bethell, C.D., Chacon, S., Biely, C., Contreras, S., Chavis, T., Bruno, Y., Moss, T., and Coker, T.R. (2017). Well-child care redesign: A mixed methods analysis of parent experiences in the PARENT trial. Available: https://www.academicpedsjnl.net/article/S1876-2859(17)30050-5/abstract.

Muñoz, R.F. (2010). Using evidence-based Internet interventions to reduce health disparities worldwide. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 12(5), e60.

Muroff, J., Robinson, W., Chassler, D., López, L.M., Gaitan, E., Lundgren, L., Guauque, C., Dargon-Hart, S., Stewart, E., Dejesus, D., Johnson, K., Pe-Romashko, K., and Gustafson, D.H. (2017). Use of a smartphone recovery tool for Latinos with co-occurring alcohol and other drug disorders and mental disorders. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 13(4), 280–290.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2015). Mental disorders and disabilities among low-income children. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/21780.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). Transforming the financing of early care and education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/24984.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). A roadmap to reducing child poverty. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/25246.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2009). Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/12480.

Nurse–Family Partnership. (2017). Nurse–Family partnership: Outcomes, costs, and return on investment in the U.S. Available: https://www.nursefamilypartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Miller-State-Specific-Fact-Sheet_US_20170405-1.pdf.

Nurse–Family Partnership. (2018a). National snapshot. Available: https://www.nursefamilypartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/NFP_Snapshot_April2019.pdf.

Nurse–Family Partnership. (2018b). Research trials and outcomes: The gold standard of evidence. Available: https://www.nursefamilypartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Research-Trials-and-Outcomes.pdf.

Ohio Attorney General’s Office. (2018). Drug use prevention resource guide. Columbus, OH: Author.

Osilla, K.C., Van Busum, K., Schnyer, C., Larkin, J.W., Eibner, C., and Mattke, S. (2012). Systematic review of the impact of worksite wellness programs. American Journal of Managed Care, 18(2), 68–81.

Paulsell, D., Del Grosso, P., and Supplee, L. (2014). Supporting replication and scale-up of evidence-based home visiting programs: Assessing the implementation knowledge base. American Journal of Public Health, 104(9), 1624–1632.

Pennant, M.E., Loucas, C.E., Whittington, C., Creswell, C., Fonagy, P., Fuggle, P., Kelvin, R., Naqvi, S., Stockton, S., and Kendall, T. (2015). Computerised therapies for anxiety and depression in children and young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 67, 1–18.

Perry, Y., Werner-Seidler, A., Calear, A.L., and Christensen, H. (2016). Web-based and mobile suicide prevention interventions for young people: A systematic review. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(2), 73–79.

Pew-MacArthur Results First Initiative. (2014). Results First in your state. Available: http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2013/results-first-in-your-state-brief2014/11/evidencebasedpolicymakingaguideforeffectivegovernment.pdf.

Pratap, A., Anguera, J.A., Renn, B.N., Neto, E.C., Volponi, J., Mooney, S.D., and Are, P.A. (2017). The feasibility of using smartphones to assess and remediate depression in Hispanic/Latino individuals nationally. Paper presented at the 2017 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and Proceedings of the 2017 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers.

PromotePrevent. (n.d.). PromotePrevent. Available: https://www.promoteprevent.com/mission.

Reach Out and Read. (n.d.). Why Reach Out and Read? How Reach Out and Read makes a difference for America’s children. Available: http://www.reachoutandread.org/our-story/why-reach-out-and-read.

Reece, J., Martin, M., Bates, J., Golden, A., Mailman, K., and Nimps, R. (2015). History matters: Understanding the role of policy, race and real estate in today’s geography of health equity and opportunity in Cuyahoga County. Columbus: The Ohio State University Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity.

Rock, A.R. (2018). Universal pre-K in the United States. Available: https://www.verywellfamily.com/universal-pre-k-2764970.

Ruzek, J.I., and Yeager, C.M. (2017). Internet and mobile technologies: Addressing the mental health of trauma survivors in less resourced communities. Global Mental Health, 4, e16.

Ruzek, J.I., Kuhn, E., Jaworski, B.K., Owen, J.E., and Ramsey, K.M. (2016). Mobile mental health interventions following war and disaster. mHealth, 2, 37.

Sampson, R.J., and Wilson, W.J. (2013). Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Storper, J. (2015). What’s the difference between a b Corp and a benefit corporation? Available: https://consciouscompanymedia.com/sustainable-business/whats-the-difference-between-a-b-corp-and-a-benefit-corporation.

Sugai, G., Horner, R., and McIntosh, K. (2016). PBIS is a multi-tiered system that is empirically validated and implemented at scale. Available: https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/sites/default/files/05_MTSS-B-Implement_2018-01-04.pdf

Thakur, K., Sudhanthar, S., Sigal, Y., and Mattarella, N. (2016). Improving early childhood literacy and school readiness through Reach Out and Read (ROR) program. BMJ Quality Improvement Reports, 5(1). doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u209772.w4137.

U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation. (2017). Building a business-led culture of health and food security. Available: https://www.uschamberfoundation.org/best-practices/building-business-led-culture-health-and-food-security.

U.S. Department of Education. (2015). U.S. Department of Education announces inaugrual education innovation and research competition. Available: https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/us-department-educationannounces-inaugural-education-innovation-and-research-competition.

Välimäki, M., Anttila, K., Anttila, M., and Lahti, M. (2017). Web-based interventions supporting adolescents and young people with depressive symptoms: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 5(12), e180.

Vigerland, S., Lenhard, F., Bonnert, M., Lalouni, M., Hedman, E., Ahlen, J., Olén, O., Serlachius, E., and Ljótsson, B. (2016). Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 50, 1–10.

This page intentionally left blank.