2

Influences on Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Development

As discussed in Chapter 1, a growing body of work has significantly strengthened understanding of the factors that influence mental, emotional, and behavioral (MEB) development from well before a child is born through adolescence, the mechanisms through which they exert that influence, and the complex interactions among them. It has long been understood that factors at the individual, family, community (including school and health care systems), and societal levels have profound effects on children’s development. Nor is it news that the ratio of positive, supportive influences to negative ones is likely worse for children born into lower socioeconomic circumstances. There is, however, growing evidence of how and when these influences, which begin before conception, promote or impede positive MEB development, and how they play out across communities and generations. This chapter first explores new perspectives on how the myriad influences on MEB development interact. It then looks in detail at the neurobiological basis for MEB development and at individual-, community-, and society-level influences.

It is important to note that this emerging picture of influences on MEB development has resulted from weaving together different sources of evidence. Both evidence collected in the laboratory about biological processes that occur at the microscopic level and sophisticated statistical analysis of large volumes of data (big data)1 have played a part. More challenging has been establishing how policies (including governmental, legal, and administrative actions, as well as the efforts of foundations and other entities) and the environments in which child development occurs are associated with outcomes for individual young people or populations.

___________________

1 The term “big data” is loosely used to refer to extremely large sets of digital data that are analyzed using computer analytics, such as, in this context, population-level surveys, birth cohort studies, and data from electronic health records that are available in large volume. The importance of these new types of data is discussed in Chapter 11 and in Appendix B.

AN INTEGRATIVE PERSPECTIVE ON MEB DEVELOPMENT

The 2009 National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (NRC and IOM) report gives careful consideration to the individual risk and protective factors that affect healthy MEB development in children and adolescents (NRC and IOM, 2009). These factors are considered within a model in which the child is at the center of concentric rings of influences, beginning with the family and moving outward to encompass school, community, and broader social influences. Subsequent developments in the science of child development have brought updates to this model, showing more clearly the interdependency among individual-level factors and the broader context in which those factors operate.

First, as we discussed in Chapter 1, models of the life course have been updated to account for the ways in which these risk and protective influences interact over time, and to reflect their importance for both individuals and populations more precisely. Second, research has produced an emerging picture of how environmental influences act at the molecular level—beginning before a child is even conceived—to generate a dynamic pathway to MEB development. Third, developing research has expanded understanding of the fundamental impact of nurturing and attachment in the earliest years and elaborated the significant concrete impacts of community- and society-level factors across developmental stages and for a range of outcomes. Finally, there is growing recognition that a child’s vulnerability, strengths, and resilience—to which biological and environmental processes contribute—also play an important role that varies over time and across family, community, and physical environments. Together, these new understandings, along with research that has harnessed large-scale datasets to investigate multiple sites and large numbers of participants across the United States, have yielded a significantly more sophisticated picture of the influences on healthy MEB development.

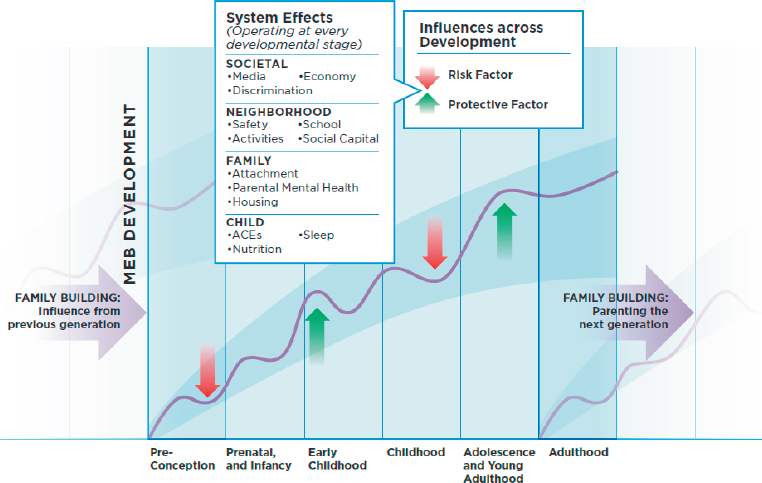

Figure 2-1 is a contextual schema showing healthy child and youth MEB development. It depicts the types of risk and protective factors that influence MEB development across the life cycle at each level (the individual child through the broader society). The horizontal arrows on each side of the figure emphasize cross-generational influences that operate at every life-cycle stage, including effects that are important even before a child is conceived and effects on the parenting of the next generation.

Since the 2009 report was published, research on the biological and environmental influences on children’s MEB health has typically focused on factors at the individual level. While this approach has identified potential contributors to the process of MEB development, it has not adequately described the process whereby a developing child is both influenced by and interacts with her socially and physically complex environment, and the ways in which both she

and her world are continuously changing.2 Although these are challenging concepts to model, researchers have developed integrative approaches that support more robust predictions of MEB outcomes and theoretical models that can be applied across contexts and populations (Martin and Martin, 2002). These models describe biological and environmental integration and the ways in which the two interact.

Biological Integration

Although neurobiological mechanisms are a central focus of research on MEB outcomes, it is important to note that these mechanisms are the downstream consequence of complex cellular and molecular variation that emerges in response to the interplay between genes and environments. Genes and environments both operate to create variation, and the interplay between these variables is the foundation for the emergence of individual variation. Moreover, there is statistical evidence for gene–environment interactions, in which genetic variations are predictive of an outcome only in the presence of specific environmental conditions, or alternatively, environmental influences on an outcome are apparent only among individuals carrying a particular genetic variant.

___________________

2 The committee recognizes that there are important questions about the use of gendered personal pronouns but that style on this issue is in flux; for clarity, we have used both “he” and “she” in this report when referring to hypothetical individuals.

Advances in molecular biology provide new insights into the nature of these interactions. Epigenetics—the environmental alteration of the genome structure through chemical processes—is an evolving field of study for researchers in child development. Epigenetics describes the chemical and molecular changes to chromatin, which include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and noncoding RNA, and how these changes influence the ways genes are expressed and shape physical and behavioral phenotypes (characteristics). These mechanisms may be modified by a broad range of environmental cues. It has been estimated that a substantial proportion of the variation in DNA methylation that occurs during the first month of life, as well as obstetric outcomes such as infant birthweight and gestational age, and even some childhood behaviors, can be explained by interactions between DNA sequence variation and aspects of prenatal environments, such as maternal smoking, depression, and body mass index (Teh et al., 2014).

Although integration of epigenetics within the framework of gene–environment interaction has broadened the biological perspective relevant to MEB health, there are still other factors to consider. The roles of epigenetic factors in neurodevelopment are also being modulated by the activity of multiple other biological systems. For example, the interactions between the immune system and the brain are critical to predicting mood, stress reactivity, and behavior. Exposure to circulating hormones has a significant role developmentally in shaping the brain and continues to influence cognition, mood, and social behavior across the life span (Engler-Chiurazzi et al., 2017; McEwen and Milner, 2017; Sisk and Zehr, 2005). Brain–gut interactions have also emerged as a developmentally important signal (influence) with potential to shape MEB health (Borre et al., 2014).

Unlike the stable and static genome, these biological systems are dynamic, which means developments in these systems are potentially reversible. Studies in rodents, for example, suggest that the microbiome (the array of bacteria found in an organ, often the intestinal tract) can be used as a target for reversing the effects of early life adversity on behavioral outcomes (Cowan, Callaghan, and Richardson, 2016), further highlighting the complex interactions among mental and physical systems and the environment. Epigenetic changes induced by adversity can also be reversed (Brody et al., 2016), which provides some hope that effective interventions can have a biological and lasting as well as immediate influence on behavioral development and behaviors.

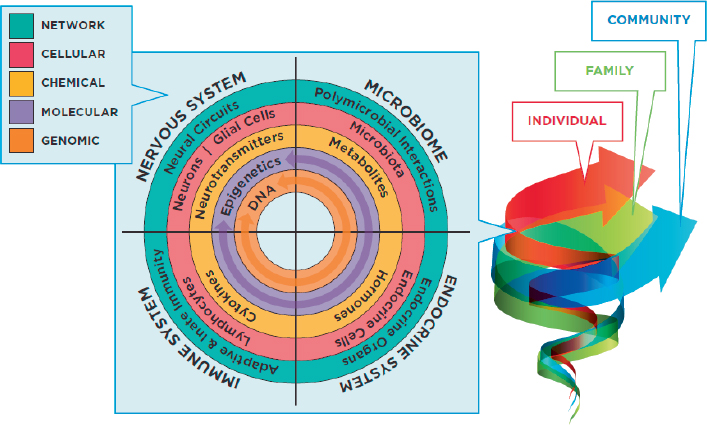

Figure 2-2 depicts the interactions among these biological factors that occur at every developmental stage. These factors may operate at the genomic level through variation in DNA sequence (the inner ring of the model in Figure 2-2), or at the molecular level through changes in how genes are expressed (the epigenetic changes represented by the purple ring). They may be reflected in chemical processes, such as hormonal changes, changes in the pathways of neurotransmitters, or changes in metabolites. Or they may occur at the cellular level through changes in the functioning of neurons, lymphocytes, microbiota, or endocrine

cells (the red ring), or changes within the networks of cells in each system, shown in the green, outermost ring.

Adopting an integrated perspective on the biology of a developing child—a perspective suggesting that a broad array of experiences shape MEB outcomes and should be evaluated—has implications for promoting MEB health. For example, research integrating health measures into the study of the development of social and academic achievement has revealed the phenomenon of “skin-deep resilience,” the idea that the occurrence of surface-level improvements in functioning (resilience) can be accompanied by a long-term biological cost, such as impaired health and biological aging (Brody et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2015). These findings further highlight the interactive influence of environment, behavior, and biology and the importance of careful consideration of how influences on MEB development affect health more broadly.

Environmental Integration

A further complexity is the influence of environmental experiences on these multilayered and interacting biological systems. Though these biological systems exist at the individual level and can be affected by the individual’s experiences, the family and the community context also shape these individual-level experiences by altering the development and functioning of biological systems, and hence MEB outcomes.

Integrative approaches are beginning to incorporate larger-scale environmental variables that may influence MEB health outcomes, although disentangling particular influences is complex. Generally, environmental factors

are conceptualized as consisting of multiple levels (i.e., individual, family, community, society) and multiple domains (i.e., social, physical), and integration of these levels and domains has typically been limited. It is possible to measure such factors, but researchers have not yet developed models of how outcomes are influenced by the interplay among proximal (e.g., family) and distal (e.g., societal) environments. This methodological limitation may in some cases lead to an overemphasis on proximal environmental cues at the expense of considering the contextual factors embedded within the community and society. This failure to address contextual factors may compromise the effectiveness of interventions targeted at the individual or family level. For example, interventions focused on individual-level anxiety may have limited effect if they do not also take into account family conflict or neighborhood violence.

The impacts of an individual’s physical environment (e.g., toxins, pollution, air quality, climate) and social environment (e.g., safety, nurturance, peer relationships, policies) are often considered separately. These qualities of the environment act on the individual organism to shift epigenetic variation and can alter neurodevelopment and the network of biological systems that interact with the brain. These exposures are also likely to co-occur, such as when a poor-quality physical environment (e.g., high pollution) is associated with low socioeconomic status. Thus, this is another area in which an integrative approach that takes such interactions and their timing into account is important. Indeed, studies of the genome or microbiome increasingly suggest that environmental factors operate not singularly but as part of a complex web of environmental and social factors that interact with child and adolescent biology and the genome, most likely through common socioemotional or biological pathways, to increase or decrease risks for unhealthy development in children.

The web of environmental variables acting at the broad societal level and the proximate social or physical levels has been termed the “exposome” to signify parallels with the genome, the proteome, the microbiome, and others (Guloksuz, van Os, and Rutten, 2018). The study of environmental variables as networks or webs of risk and protective factors will be complicated, but such research will be essential to the understanding of variation in MEB outcomes.

THE NEUROBIOLOGICAL BASIS OF MEB OUTCOMES

The development of the human brain occurs over a lengthy developmental window, starting early in fetal life and with continued structural and functional refinement being observed into young adulthood. Since the 2009 report was issued, the expanded use of neuroimaging technologies to examine brain changes from infancy through adulthood has yielded a number of important findings related to MEB development.

Developmental Acceleration

Development accelerates in response to environmental threat. For example, girls who encounter several types of challenges experience the onset of puberty earlier than girls who do not. The challenges for which these connections have been established include an absent father, maternal depression, family conflict, and low ratio of income to needs, but these effects can be buffered by secure childhood attachment (Deardorff et al., 2011; Ellis and Garber, 2000; Sung et al., 2016). Neuroimaging studies suggest that the acceleration of development is also evident in brain systems, such as those that regulate fear and learning (Gee et al., 2013), and in the connectivity between cortical and subcortical brain structures that have implications for emotional regulation (Callaghan and Tottenham, 2016). The “stress-acceleration” hypothesis collectively supported by these findings is also consistent with research showing cellular and molecular indications of accelerated biological aging including telomere length (Drury et al., 2012) and epigenetic age (Lawn et al., 2018)—biological indices of senescence that may be predictive of longevity and disease risk in children who have experienced adversity.

Differential Susceptibility and Sex Differences

Genetic, environmental, neurobiological, and behavioral characteristics account for differences in the ways individuals respond to influences such as stress or adversity. This phenomenon, known as differential susceptibility, provides a framework for thinking about ways to account for both healthy MEB development and the development of MEB disorders, a framework that focuses not on the relative vulnerability or resilience in distinct subtypes of individuals but on the degree of plasticity an individual exhibits. Cortical sensory processing capacity and the ability of the prefrontal cortex to filter emotional stimuli have been suggested as potential neural mechanisms accounting for differential susceptibility (Boyce, 2018). Increasing understanding of such mechanisms has been the basis for the development of pharmacological treatments, such as drug therapies used for depression.

One of the primary sources of variability in an individual’s developmental trajectory and response to genetic and environmental factors is biological sex. MEB outcomes are expressed differentially in males and females in response to chromosomal, hormonal, social, and broader environmental variables, and this variation is manifest in structural and functional neurobiological sex differences. These sex differences emerge early in fetal development and persist into adulthood. The interaction between sex and a broad range of influences occurring across the life span has been observed in MEB development. Accounting for the unique way in which males and females respond to these influences will be critical to predicting vulnerability or resilience to risk (Adams, Mrug, and Knight, 2018; Molenaar et al., 2019; Stroud et al., 2018). Individual vulnerability based on

gender identity has also emerged as a critical variable, as transgender and nonbinary youth are a growing proportion of the population and experience high rates of significant stressors, including bullying and lack of family support (Aparicio-García et al., 2018; Becerra-Culqui et al., 2018).

Genetic and Epigenetic Variation

The brain serves as a critical mediator of genetic and epigenetic variation in MEB development. Consistent with the move toward biological integration, establishing the impact of genetic variation on the brain’s anatomical microstructure, circuitry, and functional activation patterns will help researchers assess the mediating role of biology in MEB development. Progress is being made toward the development of a complex conceptualization of genetic influences on neurobiology that goes beyond the identification of individual genes that may account for particular phenomena by incorporating genome-wide data and more robust analytic approaches (Hibar et al., 2015). Although it is currently not possible to determine the epigenetic characteristics of genes involved in these neural phenotypes in the living brain, better understanding of the potential utility of peripheral epigenetic biomarkers (e.g., those measured in blood cells) for predicting neural epigenetic states may make predicting such characteristics and accounting for individual differences in brain and behavior trajectories feasible.

Sensitive Periods

Sensitive periods—times during which an individual’s neural development is particularly active and vulnerable—have been a key focus of research on MEB development and influences. While a cascade of neurodevelopmental events occurs from conception through adolescence, that stretch of time includes periods of intense neural plasticity during which key sensory, social, emotional, and cognitive capacities are established. Evidence that the period from birth to age 3 is one such sensitive period has been the basis for strong arguments that early intervention is important both for fostering healthy development and for preventing or delaying the onset of disorders that may disrupt subsequent sensitive periods. The period of puberty and adolescence is another time of rapid biological change, and another window for especially effective interventions. Although the importance of sensitive periods was recognized before the 2009 report was issued, recent research has shed light on the molecular pathways through which sensitive or critical periods are created (Kobayashi, Ye, and Hensch, 2015; Takesian et al., 2018). This line of research has identified strategies for reopening critical periods by increasing neural plasticity, which can result in improved sensory and behavioral outcomes. The potential to foster reversibility of deficits in MEB health through these molecular pathways may provide important insights into the mechanisms of effective interventions.

INDIVIDUAL INFLUENCES

Given the essential interconnected nature of environmental influences and neurobiological development, it is useful to examine the mechanisms through which physical, social, and other experiential factors influence development for individuals. These factors range from parents’ exposures to toxins before they even conceive a child to stresses or depression in adolescence that carry over into the individual’s later experience of conception and childbirth.

Preconception and Prenatal Factors and Premature Birth

The literature concerning parents’ influences on their children’s birth and MEB developmental outcomes is extensive but has not yet settled many important questions. Researchers have provided a clear picture of prenatal and postnatal influences on MEB outcomes, but much more work is needed to fully explain how preconception factors shape those outcomes. It is clear that these factors exert both direct and indirect influences. Direct exposure to preconception and prenatal influences, such as toxins or diet during pregnancy, may affect MEB health and development. Similarly, birth outcomes such as gestational age and weight at birth, which may be the consequence of preconception and prenatal factors, are also known to influence later MEB outcomes.

Preconception

There is strong reason to believe that both men’s and women’s exposures to a broad range of factors both physical (e.g., toxins, drugs) and social (e.g., stress)—even before they conceive a child—can affect that child’s MEB development. While such exposures have been associated with undesirable outcomes for children, the links have not been strongly established, and little is known about the pathogenic mechanisms involved. However, there is evidence that events occurring before pregnancy, such as high-level stress, influence pregnancy outcomes such as preterm birth, which in turn affect MEB development (Cheng et al., 2016).

Since the 2009 report was issued, research has increasingly focused on the preconception period. Epidemiological data support the hypothesis that maternal and paternal preconception exposures and experiences have important influences on the child later conceived (Stephenson et al., 2018; Witt et al., 2016). Perinatal depression often occurs in women who had mental health problems prior to conception (Patton et al., 2015). Similarly, for women there is an association between self-harm during young adulthood and both future perinatal mental health concerns and difficulties with mother–infant bonding (Borschmann et al., 2018). Although women often modify behaviors that could harm their fetus once they learn they are pregnant, the fetus may still have been exposed during an especially vulnerable time.

Studies of both animals and humans have indicated that the epigenetic effects of parental preconception exposures that influence neurodevelopmental and behavioral traits in offspring may persist across generations, and that parental exposure to a broad range of substances and psychosocial stressors can be associated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes (Knezovich and Ramsay, 2012; Zuccolo et al., 2016). Another clue is provided by research on the degree to which a pregnancy was planned, which may coincide with other parental socioemotional and physical contextual factors during preconception and beyond (Saleem and Surkan, 2014). Growing evidence of the concerning effects of events occurring prior to conception has led the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to issue recommendations regarding the planning of parenthood following potentially risky exposures (Knezovich and Ramsay, 2012).

The Prenatal Period

Gestation is a period of rapid neurodevelopmental change in the fetus, during which all of the fundamental processes of brain development that build the foundations of the adult brain are taking place. The plasticity occurring during this developmental window makes it a period of heightened risk for neurodevelopmental disruption, which can have implications for neurocognitive and neurobehavioral outcomes. Risk factors associated with adverse development include in utero exposure to cigarette smoke, alcohol, illicit drugs, some prescription drugs, and toxins; poor nutrition; maternal immune activation; maternal psychopathology; and maternal exposure to stress. For example, emerging evidence suggests that maternal depression and anxiety may be associated with the development of brain white matter microstructure in infancy, although how this phenomenon affects the child’s MEB outcomes is yet to be determined (Dean et al., 2018).

These factors may affect MEB development through multiple routes, including direct exposure-related interactions with the developing fetal brain and exposure effects on the placenta that affect the transfer of oxygen and nutritional resources and hormonal gatekeeping between mother and fetus (Monk, Spicer, and Champagne, 2012). These factors may also have effects on postnatal mother–infant interactions. Since the 2009 report was issued, understanding of the mechanistic pathways through which a broad range of prenatal influences affect child and adolescent MEB outcomes has expanded to include epigenetic changes within the placenta and in offspring, immune dysregulation, and structural and functional neurobiology.

These prenatal effects may serve as predictors of aspects of MEB development, such as cortisol reactivity, self-regulation (Conradt et al., 2015), and cognitive development (Tilley et al., 2018). Researchers have used the ability to monitor and image the brain during the prenatal period to develop new insights into the timing of the neurodevelopmental cascade that contributes to MEB vulnerability and resilience.

There have been increasing concerns about the influence of pharmacological treatments given during pregnancy on fetal and infant outcomes. Depression medications taken by mothers may be associated with changes in fetal brain development, although further research is needed to trace the potential influences on MEB development (Lugo-Candelas et al., 2018; Malm et al., 2016). However, untreated maternal depression can also be a serious risk factor for the health of both mother and child, and treatment with psychotropic medications during pregnancy can be indicated when other approaches (nutritional, behavioral, or psychotherapy-based preventive interventions) are not effective on their own or when women do not have access to those alternatives (Vigod et al., 2016). Optimal means of promoting maternal physical and psychological health before and during pregnancy will be an important direction to explore in future work (see Chapter 3 for further discussion of these issues [Bramante, Spiller, and Landa, 2018]).

Preterm Birth

Perhaps the most pernicious risk factor associated with the perinatal period (the time from earliest viability of the fetus through the first 4 weeks after birth) is preterm birth, defined as delivery before 37 weeks of gestation. This outcome occurs in almost 10 percent of pregnancies in the United States, with black mothers having higher rates (14%) than their white counterparts (9% [Martin and Osterman, 2018]). The frequency and severity of adverse MEB outcomes increase with decreasing gestational age and birthweight. Extremely premature babies have the highest incidence of undesirable outcomes, such as periventricular hemorrhage, strokes, and other catastrophic brain injuries. These children are at higher risk for manifesting cognitive deficits, impaired executive functioning, depression, anxiety, autism spectrum disorders, and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Hack et al., 2009; Singh et al., 2013). Although the frequency and severity of adverse MEB outcomes are generally higher the lower the baby’s gestational age and birthweight, neurodevelopmental disorders that may be more subtle are also observed among infants born early but closer to term (Franz et al., 2018).

The prevalence of premature birth in the United States had been steadily declining from 2007 to 2014, coinciding with public health campaigns to decrease teen birth rates (Ferré et al., 2016). Since 2014, however, its prevalence has been on the rise, particularly among non-Hispanic black women (Martin and Osterman, 2018). Other factors have been associated with preterm birth,2 but relatively little progress has been made in reducing the likelihood of this outcome.

___________________

2 For more on causes of preterm birth, see https://www.nap.edu/catalog/11622 (IOM, 2007).

Infancy and Childhood

Infancy and childhood are a period of continued neuroplasticity and behavioral development, and the first 3 years of life are a time of particularly rapid neurodevelopment. Advances in neuroimaging techniques and applications have provided more in-depth insights into the changes that characterize children’s developmental trajectories and the ways in which these trajectories are altered by a broad range of genetic, physiological, and experiential factors. During this period, the experiences of the infant and child are shaped predominantly by the quality of interactions with caregivers; researchers have recently focused on how sensory and socioemotional interactions with parents can affect MEB development.

Research has shown that mothers affected by postpartum depression have fewer positive interactions with their babies and more negative ones (including both over- and understimulation), compared with those not affected by this condition (Beebe et al., 2011; Field, 2010; Hummel, Kiel, and Zvirblyte, 2016; Mantis et al., 2019). Research also has shown that infants of mothers with postpartum depression demonstrate greater incidence of a number of problems, including slower cognitive development; problems with secure attachment; increased risk of behavioral difficulties; and more depressive interaction styles, including more crying and gaze avoidance, compared with infants of non-depressed mothers (Bigelow et al., 2018; Granat et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017; Priel et al., 1995, 2019). Moreover, infants and children of depressed mothers are at higher lifetime risk for major depression and other mental disorders (Hammen, 2018; Netsi et al., 2018; Shen et al., 2016; Weissman et al., 2016).

Nurturing interactions may be particularly important for infants and children who have experienced adversity during earlier developmental stages. For example, preterm infants exposed to increased caregiver interactions exhibit improved neurodevelopmental and behavioral outcomes (Welch et al., 2015, 2017). Likewise, infants that have experienced severe social deprivation through institutional rearing can show significant cognitive and socioemotional improvements following adoption (Nelson, Zeanah, and Fox, 2019), and there is evidence that the quality of parent–child interactions is a significant mediator of improved MEB outcomes in previously institutionalized children (Harwood et al., 2013). Neglect or institutional rearing can induce epigenetic and neurodevelopmental changes that coincide with other broad biological changes in immune, hormonal, and microbiome systems that influence MEB development (McLaughlin, Sheridan, and Nelson, 2017). Evidence of changes to these systems following interventions involving improved caregiver–child interactions (Bick et al., 2019; Naumova et al., 2019) illustrates potential opportunities to reduce the likelihood of MEB disorders.

Adverse Childhood Experiences

The term adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) encompasses a variety of traumatic experiences, such as physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and neglect (including peer bullying), that occur before a child turns 18. In a measurement of nine ACEs, the 2016–2017 National Survey of Children’s Health found that 20.5 percent of children had experienced at least two of them. For children with special emotional, behavioral, or developmental health care needs, that proportion increases to 46.2 percent (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, n.d.).

ACEs have been studied extensively over several decades and have been correlated with negative MEB outcomes, such as depression, suicide, substance use, and risky sexual behavior (Hillberg, Hamilton-Giachritsis, and Dixon, 2011; Norman et al., 2012). They are also correlated with poor social relationships, social rejection, and association with deviant peers. Furthermore, substantial evidence points to the critical importance of secure attachment relationships with caregivers and peers that promote warmth and provide consistent social interactions (see below). The absence of warmth and stability and the presence of disruptive and unrelenting (toxic) stress-inducing interactions are sources of lasting biological and behavioral changes. These changes are evident in heightened stress reactivity, biological aging (decreased telomere length and increased epigenetic age), neurodevelopmental disruption, and impairments in all of the domains of functioning necessary for healthy MEB development (Britto et al., 2017; Garg et al., 2018; Ridout, Khan, and Ridout, 2018).

Researchers have not conclusively identified causal relationships between ACEs and such effects, and it is possible that the same factors that cause poor mental health also contribute to ACEs. Experiences with parental psychopathology and substance use (discussed above), for example, have been linked to increased rates of psychiatric disorders and subsequent poor social functioning in offspring (Field, 2010; Goodman et al., 2011; Gureje et al., 2011; Stein et al., 2014). In a meta-analysis of 114 studies examining the effects of childhood exposure to violence, posttraumatic stress symptoms were equally associated with direct victimization and with witnessing or hearing about violence (Fowler et al., 2009). ACEs in early childhood have been associated with a cascade of immediate and long-term effects that manifest in problem behaviors in school and peer contexts. Parents’ own ACEs also have a negative effect on the neurobehavioral development of their own children (Folger et al., 2018).

ACEs are associated with adverse outcomes that last into adulthood. Adults who have had such experiences as children (including maltreatment, parental mental illness or substance use, and household disruptions such as parental incarceration and divorce) have an increased risk of psychological, behavioral, and physical health conditions, although it is possible that these conditions have an inherited component (Bethell et al., 2014; Felitti et al., 1998). The early work in this area has been confirmed by a recent meta-analysis of 37 studies demonstrating the relationship between adverse experiences and health (Hughes

et al., 2017). This work has shown that stressful childhood experiences are associated with an increased likelihood in adulthood of inflammatory processes, stress reactivity, cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disorders, and premature death, as well as depression, antisocial behavior, and substance abuse (Schilling, Aseltine, and Gore, 2007).

There is some evidence that the adverse outcomes associated with ACEs can be mitigated by promoting healthy MEB development in children and youth. For example, interventions that support parents and schools in preventing traumatic events such as child abuse and bullying can promote resiliency (Bethell et al., 2016; NASEM, 2016a, 2016b). Resiliency, defined as “staying calm and in control when faced with a challenge,” is associated with higher rates of school engagement among children with adverse childhood experiences (Bethell et al., 2014).

Peer Influence

Negative peer influence has been well established as a risk factor for the development of multiple MEB disorders, including antisocial behavior; use of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs; risky sexual behavior; and academic failure (Ary et al., 1999; Biglan et al., 2004; Duncan et al., 1998). At the same time, peers also influence the development of normative behaviors (Laninga-Wijnen et al., 2016). Indeed, some experimental evidence indicates that when adolescents receive encouragement to engage in specific prosocial behaviors from an unfamiliar peer, they are more likely to engage in those behaviors, especially if the peer has high social status (Choukas-Bradley et al., 2015). Young people’s development of self-control skills is also associated with greater peer support (Orkibi et al., 2015). Still other evidence has shown that peers can buffer the effects of harsh parenting on adolescent depression (Rusby et al., 2016; Tang et al., 2017).

Another way in which peers influence each other’s behavior is through bullying and harassment. More than 20 percent of students ages 12–18 have experienced bullying at school (e.g., mockery; insults; name calling; or physical actions such as shoving, tripping, or spitting), and of those who report being bullied, 33 percent say it occurs at least once or twice per month (PACER’s National Bullying Prevention Center, 2017).3 Nearly 60 percent of teens report that they have experienced some form of cyberbullying, such as name calling, spreading of false rumors, and physical threats (Anderson, 2018). Youth who bully have been shown to be more likely to use drugs later in life (Ttofi et al., 2016), while victims of bullying are at increased risk of behavioral and mental health problems and also have poorer school attendance and lower academic performance (Gardella, Fisher, and Teurbe-Tolon, 2017; PACER’s National Bullying Prevention Center, 2017).4 There is an association as well between both

___________________

bullying and being bullied and other adverse childhood experiences (Forster et al., 2017). A longitudinal study of students who reported exposure to harassment in middle school found that this harassment predicted association with deviant peers, more aggressive and antisocial behavior, and more cigarette smoking in high school (Rusby et al., 2016). Further investigation of the interplay among the social and emotional roots of these issues will be valuable.

Adolescence

Adolescence is a time of numerous physiological, cognitive, and emotional developmental changes that occur in the context of rapid physical growth. These changes do not always occur in sync. For example, many teens develop physically and sexually by their midteens while brain development is continuing; maturation occurs earlier for females than for males, but for males it continues until about age 25. This gap between brain development and other aspects of development creates a window in which MEB disorders, such as depression, can emerge. In addition, inadequate development of self-control skills can lead to hypersensitivity to reward- and risk-seeking behaviors.

In the past decade, there has been considerable progress in understanding of the neurocognitive development that occurs during adolescence. Research has identified a number of neurobiological markers that predict the onset and escalation of mental health disorders, as well as treatment outcomes. For example, volumetric alterations in frontal, limbic, and white matter structure detected through magnetic resonance imaging are predictive of the onset of adolescent depression (Pagliaccio et al., 2014; Whittle et al., 2011). Additionally, social determinants are critical during adolescent development. Recent reviews provide compelling evidence that poverty (Yoshikawa, Aber, and Beardslee, 2012), racism and discrimination (Priest et al., 2013), and other social determinants affect the health and well-being of these young people.

Protective Factors in Adolescence

While the IOM 1994 and NRC and IOM 2009 reports focused on risk factors and pathology, many researchers in the past decade have pivoted to focus on the factors that promote positive mental health and support adolescents in overcoming disadvantage or adversity (Dray et al., 2017; Lee and Stewart, 2013). This work has identified a number of protective factors for fostering healthy MEB development, including strong attachment to family; high levels of prosocial behavior in family, school, and community; high social skills/competence; strong moral beliefs; high levels of religiosity; a positive personal disposition; positive social support; and strong family cohesion (see https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/protective/resources.htm). These factors are associated with lower levels of anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, stress, and obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents (Bond et al., 2005; Hjemdal et al., 2007, 2011).

These factors appear to be protective across racial/ethnic groups and socioeconomic status. A recent review found that for at least one racial/ethnic group and in at least one risk context, the following factors were protective: employment, extracurricular activities, father–adolescent closeness, familism (priority of the family’s needs over the needs of any one member), maternal support, attending predominately minority schools, neighborhood composition, nonparent support, parental inductive reasoning, religiosity, self-esteem, social activities, and positive early teacher relationships (Scott, Wallander, and Cameron, 2015).

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

For many young people, questions about their sexual orientation and gender identity become a focus as they are undergoing puberty, and for some, they arise even earlier. Those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer or are nonbinary (LGBTQ+) can be vulnerable for a variety of reasons that may have significant implications for their mental and emotional health.5 The process of recognizing and understanding sexual orientation and gender identity may be stressful for adolescents if they are not supported, and bias-based bullying or victimization also harm MEB health (Russell and Fish, 2016).

Existing research offers insights into both risk factors for adolescents who self-identify as LGBTQ+ and factors that tend to offer protection. A recent systematic review of the psychosocial risk and protective factors for depression among LGBTQ+ adolescents found that among the sexual orientation and gender identity stressors reported by adolescents, the most prominent risk was an association between internalizing negative societal attitudes and beliefs and depression (Hall, 2018). The adolescents studied also cited stress related to managing, hiding, and disclosing their LGBTQ+ identity (coming out). Other work has suggested that, relative to non-LGBTQ+ youth, LGBTQ+ adolescents are more likely to experience depression, consider suicide, and experience bullying (Elamé, 2013; Hall, 2018; Kann et al., 2016; Peguero, 2012; Russell and Fish, 2016; Toomey, Syvertsen, and Shramko, 2018).

A number of protective factors for MEB disorders among LGBTQ+ youth have also been identified. Strong evidence indicates that feeling connected, particularly with a parent, but also with nonparental adults and a positive school environment, confers protection against such risks as nonsuicidal self-injury, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation (Taliaferro, McMorris, and Eisenberg, 2018). A systematic review of protective factors for depression among LGBTQ+ adolescents, for example, found positive relationships with family and friends to

___________________

5 We note that categories of gender and sexual identity continually evolve and that existing studies of the relationship between sexual orientation and gender identity and MEB health have focused on varying populations. For more on sexual orientation and gender identity, see https://gaycenter.org/about/lgbtq.

be important in mitigating depression and promoting mental health (Hall, 2018). This research suggests that feelings of connection and safety within the adolescent’s social ecology likely support and facilitate strategies for coping with stressors and negative experiences. A few studies have examined the interaction between racial/ethnic identity and gender/sexual identity among adolescents (see, e.g., Burns et al., 2015; Kertzner et al., 2009; Mustanski and Liu, 2013), but this work has not yet supported consistent conclusions, and this is another area warranting further study.

Lifestyle Factors

An individual’s immediate environment is characterized by behavioral and lifestyle factors that influence physical health at all ages. Health and lifestyle are interdependent, an integrative biological–environmental unit that is shaped by the individual’s household and the lifestyles of close peers. Lifestyle factors linked to MEB health include sleep, exercise, nutrition, relaxation, recreation, and relationships (Walsh, 2011). There is reason to believe, however, that a significant proportion of young people are not benefiting from these lifestyle factors. For example, a survey of U.S. 8- to 11-year-olds showed that just one-half or fewer were meeting such targets as engaging in 60 minutes of physical activity per day, limiting screen time to less than 2 hours per day, and getting 9 to 11 hours of sleep per night (Walsh et al., 2018).

Lifestyle factors have the potential to influence MEB outcomes at a population level across ages, genders, geographic locations, and socioeconomic strata, as well as at a family level. These factors are also interdependent: improvement (or decline) in one lifestyle factor can influence another and amplify effects on MEB development (Chennaoui et al., 2015; Miller, Lumeng, and LeBourgeois, 2015). The evidence for specific claims about lifestyle factors is mixed, as reviewed below.

Physical Activity and Nutrition

While there is evidence supporting the association between physical activity and depression in adults (Morres et al., 2019; Schuch et al., 2016), the evidence is less conclusive for children and youth (Biddle et al., 2019). A recent review found support for a causal association between physical activity and cognitive functioning, but only partial support for a link between physical activity and depression in young people (Biddle et al., 2019). Associations between physical activity and mental health in both young and older people are repeatedly reported in the literature, but the research designs of such studies are frequently weak, and reported effects are generally modest. The most consistent associations occur between sedentary screen time and poorer mental health, especially anxiety and depression (Biddle and Asare, 2011). The overall grade on a report card on physical activity for U.S. children and youth was a D— (Katzmarzyk et al., 2016).

A rich literature addresses the relationship between nutrition and neurobehavioral development, primarily but not exclusively consisting of studies conducted with animals (Smith and Reyes, 2017). This research suggests that maternal and early childhood nutritional effects may manifest in epigenetic changes that persist across the life span (Liu, Zhao, and Reyes, 2015). Food scarcity and diets consisting of unhealthy foods may both be risk factors for suboptimal MEB development (Kimbro and Denney, 2015; McLaughlin et al., 2012).

Likewise, obesity—a problem for a large segment of children and adolescents, as well as young adults—is associated with an array of behavioral disorders in childhood (Small and Aplasca, 2016), and some antipsychotic medications may induce weight gain (Dayabandara et al., 2017). Whether obesity contributes to unhealthy MEB development or is the result of behavioral dysfunction, the association is strong, and reducing obesity is likely to foster healthier MEB development.

Sleep

Sleep quality and quantity are both influenced by environmental factors and associated with MEB health outcomes across the life span. Sleep insufficiency in childhood is the result of both individual factors, such as obstructive sleep apnea, and environmental factors, including chaotic households, lack of a bedtime routine, and nighttime engagement with electronic devices. Sleep serves a number of critical roles, supporting processes including memory consolidation (Feld and Born, 2017) and emotional processing (Altena et al., 2016), and promoting neural plasticity (Abel et al., 2013). Bidirectional effects of sleep on MEB health are also suggested by the high comorbidity of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders and sleep disruption. Examples include children with obstructive sleep apnea, who experience more ADHD and mood disorders, and children with autism spectrum disorder, for whom sleep is often a major challenge. Concern is also increasing that physical and social environments that include high levels of noise (Halperin, 2014) and light exposure (including from electronic devices) may disrupt sleep, with consequences for metabolism, stress physiology, neurobiological function, and the emergence of cognitive and emotional disorders (Cain and Gradisar, 2010).

Technology Use and Screen Time

A significant development since publication of the 2009 report has been the increase in access to social media among children and youth. Young people are much more involved in unmonitored social interactions on the Internet and social media than ever before (or than adults are). The Pew Research Internet Project found that 95 percent of 13- to 17-year-olds had a smartphone or access to one, and 45 percent said they were online on a near-constant basis (Anderson and Jiang, 2018). Ninety-seven percent of online teens reported using some sort of

social media: YouTube (85%), Instagram (72%), Snapchat (69%), Facebook (51%), and Twitter (32%) (Anderson and Jiang, 2018). Social media can be socially isolating for some children and adolescents or create a forum for negative social interactions, though it also can facilitate contact with peers (Adams, Daly, and Williford, 2013; Lee and Horsley, 2017).

Research on connections between social media and MEB health is relatively sparse. A 2014 literature review highlights some concerning signs, such as bullying on social media and social media’s capacity to foster risky behaviors, such as suicidal thinking, self-harm, and drug and alcohol abuse (Patton et al., 2014). A few other studies have indicated that exposure to bullying on social media is linked to adolescent suicides, internalizing symptoms, concurrent and later depression, and social anxiety (Landoll, 2012). On the other hand, one study suggests potential benefits of young people’s social media interactions, such as the availability of anonymous contact with nonjudgmental peers and the possibility that others may intervene in response to such warning signs as suicidal ideation (Robinson et al., 2016). This is an important area for further study.

Interaction with technology (which can be defined as the quality and quantity of time spent viewing digital programming or using a computer or mobile device) is a lifestyle factor that can either enhance or interfere with healthy MEB development among children and youth, and is another area in which research is emerging (Radesky and Christakis, 2016). While access to high-quality digital content or information available online has benefits, excessive exposure and exposure to inappropriate content have potential negative effects. For example, negative behavioral effects of extended or inappropriate exposure have been observed at all childhood and adolescent ages (American College of Pediatricians, 2016). The possible consequences for MEB health of excessive screen time and exposure to media violence may include increased calorie intake (snacking) and decreased physical activity, both of which contribute to overweight and obesity; sleep insufficiency; social isolation; and addiction to video games (American College of Pediatricians, 2016; Anderson et al., 2017; Busch, Manders, and de Leeuw, 2013; Carter et al., 2016; Glover and Fritsch, 2018).

FAMILY INFLUENCES

The quality of parenting or caregiving within the home or family is a strong determinant of MEB outcomes. It is also within the family that intergenerational factors influencing children’s MEB development play out. Thus, a better understanding of the features of a family and the family processes that shape the quality of this environment is essential.

It is important to consider how a family is defined. The traditional definition of parents as a child’s biological mother and father has evolved to include heterosexual, gay, and lesbian parents; single individuals; caretaking family members; and parents who use assisted reproductive technologies such as in vitro fertilization, egg donation, sperm donation, embryo donation, or surrogacy (Golombok, 2017). Moreover, the concept of a family now encompasses

- the biological parents who carry the child’s genes;

- the environmental family, that is, the biological and nonbiological relatives or cohabitants with whom the child lives; and

- the caretaking family, who may or may not overlap with the above individuals and may or may not live with the child (Weissman, 2016).

Family factors are the most well-studied and most proximal influences on a child, especially the child’s early development. Researchers have focused on familial breakdown and negative parenting that result in frequent disputes, neglect, parental coldness, and physical aggression—all of which appear to have negative consequences for children’s MEB development (Golombok et al., 2017). However, it is important to distinguish between modern families that exemplify new configurations and families whose structure has been shaped by the breakdown of relationships or parental distress. We discuss three areas in which research has provided a relatively clear picture of connections between attributes of family life and MEB development: parenting and family stability, substance use, and effects of chronic illness and severe health problems in children and youth.

Parenting and Family Stability

Parents play a pivotal role in shaping the MEB health of their offspring from infancy through young adulthood and beyond. Parenting practices, including how children are disciplined, praised, monitored, engaged in verbal interactions, and provided with a secure environment, are key risk and protective factors for children’s MEB functioning, helping to develop their self-concept, their capacity to identify and evaluate stressful events, and their coping strategies. Further, consistent interactions and secure attachment between parents and children have promotive and protective effects on children’s MEB development (Bethell, Gombojav, and Whitaker, 2019; Bowlby, 1988; Brumariu and Kerns, 2010; Kerns and Brumariu, 2014; NASEM, 2016b; Sonuga-Barke et al., 2017).

Researchers have established both that positive parenting is important to healthy MEB development and that it can be taught (e.g., Office of Adolescent Health, 2019; Ryan, O’Farrelly, and Ramchandani, 2017; Stafford et al., 2016). At the same time, research has associated coercive family processes (interactions characterized by hostility or those in which some family members are demeaned or controlled through punitive behavior) with the development of aggressive behavior, and also with a developmental trajectory that makes academic failure, delinquency, violent behavior, depression, and substance use more likely (Dishion and Snyder, 2016; Patterson, Forgatch, and Degarmo, 2010). Coercive family processes are also associated with marital discord and maternal depression (Del Vecchio et al., 2016). Similar evidence indicates that reducing punitive practices in schools is associated with improved academic performance and increased prosocial behavior and the prevention of diverse behavioral problems (Beets et

al., 2009; Durlak et al., 2007; Flannery et al., 2003; Horner et al., 2009; Snyder et al., 2010).

Given the key role of the family in promoting healthy MEB development and preventing MEB disorders, it is important to observe that research from the past 10 years suggests that the family may be under greater threat than in the past (AEI/Brookings Working Group on Poverty, 2015). The disruption of parental relationships may result in lower family income and reduced psychological and social support for children’s development. Social stress in the family is also associated with an increased risk of academic failure, school dropout, teenage pregnancy, drug and alcohol use, and psychological disorders, as well as with earlier onset of puberty in girls (Webster et al., 2014).

Substance Use

Substance use disorder is a major public health concern. The use of substances and their detrimental effects can start during adolescence or earlier and have lifetime as well as intergenerational sequelae. About 12.3 percent of children under 17 live in households with at least one parent with a substance use disorder (predominantly alcohol), and parents’ substance use has major impacts on their children’s MEB development (Lipari, 2017; Smith et al., 2016). These parents have an increased likelihood of financial difficulties and elevated risks for unstable living conditions and frequent moves, legal problems, and parental conflict (Barnard and McKeganey, 2004; Keller et al., 2002). Children born to mothers who are actively abusing substances are at risk for lower birthweight, feeding difficulties, increased irritability as infants, and stunted cognitive and physical development (Behnke and Smith, 2013). Children whose parents or caregivers have substance use disorder are also at higher risk for less secure attachment, physical abuse, and poor emotional development (Osborne and Berger, 2009).

The children of parents with substance use disorder also are at increased risk of having substance use problems and other mental health disorders. These children experience increased rates of family conflict and poor parenting practices, including failure to set guidelines, monitor children’s behavior, and provide appropriate consequences, in affected families (Accornero et al., 2002; Brook, Brook, and Whiteman, 2003; Fals-Stewart et al., 2004; Teti et al., 1995). A longitudinal study of nearly 5,000 children born between 1998 and 2000 that examined several questions about families at risk demonstrated that children of parents with a substance use disorder, especially when both parents had the disorder, were more likely to have increased symptoms of aggressive, oppositional defiant conduct, and anxiety/depression disorders (Osborne and Berger, 2009).6

___________________

6 For more about this study, see https://fragilefamilies.princeton.edu/publications.

Effects of Chronic Illness and Severe Health Problems

The prevalence of chronic health conditions and disabilities among children and youth has increased over the past century, primarily because of four conditions: asthma, obesity, mental health conditions, and neurodevelopmental disorders (Perrin, Anderson, and Van Cleave, 2014). While there have been reductions in the impact of other conditions, severe ongoing health problems are also increasing, and have been estimated as affecting approximately 1 in 20 children and youth (Boat, Filigno, and Amin, 2017). These increases reflect improved treatments and decreased mortality rates, and may also reflect changes in diagnostic standards and screening, such as those that have resulted from research on ADHD.7

Chronic disorders can have adverse consequences for the MEB health of those affected and the functioning of their families. Anxiety, depression, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are more prevalent in these young people than in the population of children and youth at large (Bethell, Gombojav, and Whitaker, 2019; Wilcox et al., 2016). Life-threatening and disabling chronic disorders also are a frequent factor in parental anxiety and depression, which pose a major risk to parenting adequacy (Boat, Filigno, and Amin, 2017). Caring for children with such a disorder is a challenge that affects the entire family. A study of families with children affected by cystic fibrosis, type 1 diabetes mellitus, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and sickle cell disease found that, in general, parents had less time to engage in activities with their children, more family conflict, and less problem solving compared with control parents who did not have a child with a complex medical condition (McClellan and Cohen, 2007). Another study (Spieth, 2001) found that families with a child with cystic fibrosis scored lower on the domains of family communication, involvement, affect management, and behavior control. Parental separation, distancing, and disengagement are common. Mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms are frequent in parents of affected children, often surfacing soon after the child’s diagnosis (Quittner et al., 2014). All of these findings reinforce the relationships between physical and mental health, as well as the key role of family functioning.

COMMUNITY- AND SOCIETY-LEVEL INFLUENCES

The majority of prevention science research over the past 40 years has focused on identifying individual and proximal risk and protective factors that influence MEB development, with an eye to devising interventions that may alter these factors. Researchers have also been interested, however, in how the

___________________

7 Estimates of prevalence vary depending on definitions (Perrin et al., 2012 [https://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/33/3/99)]). For discussion of means of identifying children with chronic or special health care needs, see Bethell et al. (2015; [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4778422/]).

characteristics of local communities and the broader society influence outcomes for young people. This emphasis, as discussed in Chapter 1, has grown in recent years and is an important focus of this report. Indeed, it only makes sense that healthy communities play a key role in shaping the social, economic, and environmental conditions in which children and families live, learn, work, and play, and that in turn have a major influence on young people’s MEB health. As the authors of a recent economic assessment of the links between early life experiences and long-term outcomes put it, “relatively mild shocks early in life can have substantial negative impacts,” though the effects are heterogeneous, reflecting the myriad differences among individuals, families, and social circumstances (Almond, Currie, and Duque, 2018, p. 1360).

The sorts of evidence that have established associations between the characteristics of communities and society and outcomes for children and youth are somewhat different from those regarding influences at the individual and family levels because the connections are more distal. That is, associations between exposure to toxins and neurological development or between parenting practices and MEB health are fairly direct (proximal), whereas associations between the characteristics of a neighborhood or city and outcomes for the young people who live there are more indirect (distal), requiring different research approaches. We look briefly here at the research that has explored community- and society-level influences on MEB development.

Community Influences

To illustrate how the community environment can affect child development, we explore evidence on three elements of community: neighborhood attributes, school organization and characteristics, and foster care.

Neighborhood Attributes

Researchers in fields including public health and economics explore population-level connections between social determinants of health—the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, including health systems—and how long and how well they live. When children and families have access to social, economic, and physical resources that promote health and wellbeing (e.g., safe and affordable housing, quality education, public safety, availability of healthy foods, and safe play spaces), they have more opportunities to thrive (National League of Cities, 2009). Conversely, children growing up in communities that lack these positive environmental conditions tend to suffer poorer health outcomes relative to their peers (National League of Cities, 2009).

Researchers have pointed to the overpowering risk for developmental, cognitive, and affective problems among children whose families have lived in impoverished urban neighborhoods or isolated rural areas across multiple generations (Collins et al., 2009; Wodtke, Harding, and Elwert, 2011). In addition,

longer residence in such neighborhoods is associated with multigenerational epigenetic changes and multiplicative education and health problems for children (McEwen, 2017; Sharkey and Faber, 2014).

Policies at the local and federal governance levels have contributed to multigenerational poverty in inner-city neighborhoods. Research has documented structural racism in employment and housing policies, such as the redlining (discriminatory lending practices) in African American neighborhoods by federal housing authorities, which continued into the 1970s and later was practiced by commercial banks (Greene, Turner, and Gourevitch, 2017; Hall, Crowder, and Spring, 2015). Similar discrimination has been identified in veterans’ home loan programs and employment programs (Sampson and Wilson, 2013), as well as city services and investments in minority communities (Reece et al., 2015). Data from Cleveland, Ohio, illustrate this connection. In a small number of neighborhoods that were affected by discriminatory policies during the mid–20th century, rates of black infant mortality, gun deaths, and school dropout are three times higher than city averages. No single risk factor accounts for these differences other than residence in one of these neighborhoods (Reece et al., 2015). Similar associations between policy and MEB disorders have been documented in some rural areas (Kelleher and Gardner, 2017).

School Organization and Characteristics

School plays an important role in children’s development, beginning in the earliest years. For example, work in the past decade has suggested that students in school environments characterized by supportive and nurturing relationships among teachers, staff, and students; a sense of physical and emotional safety; and shared learning goals across multiple school stakeholders tend to have fewer mental and emotional problems and greater academic success than their peers in school settings that lack some or all of these attributes (Cohen and Geier, 2010; Lee, 2012; Wang, 2009; Yang et al., 2018). Other work has shown that peer support and school safety are associated with reductions in bullying behavior (Konishi et al., 2017). A positive school climate has also been shown to moderate the negative outcomes and foster better outcomes for LGBTQ+ students (Birkett, Espelage, and Koenig, 2009). Likewise, research on the school characteristics that yield the greatest improvement for students, based on longitudinal data, has shown the power of the school community, including parent engagement and a student-centered learning climate (Bryk et al., 2010).

Other research has examined what is called an authoritative school climate, one characterized by a strict but fair disciplinary structure and students’ perception that school staff treat them with respect and genuinely want them to succeed. This type of climate has been found to support students’ motivation to achieve by fostering their engagement with school and reducing peer victimization (Cornell, Shukla, and Konold, 2015; Wang and Eccles, 2013). It is important to note here the racial/ethnic disparities in students’ perceptions of school climate. Black students report fewer positive school experiences than white

students, regardless of socioeconomic status and diversity within the school (Bottiani, Bradshaw, and Mendelson, 2014, 2016).

The role of teachers’ social and emotional competence and well-being and the working conditions that support their job satisfaction and well-being have also been studied (Greenberg, Brown, and Abenavoli, 2016; Kraft and Papay, 2014). Teachers report the highest stress levels of all occupational groups (45% [Gallup, 2014]), and in a recent survey of K–12 public school teachers, 59 percent reported regularly experiencing great stress, an increase from 35 percent of teachers who did so in 1985 (Markow, Macia, and Lee, 2013). This survey also showed a significant decrease in job satisfaction among teachers, from 62 percent in 2008 to 39 percent in 2012.

When teachers regularly experience high levels of stress and negative emotions, it can have a negative impact on their students’ behavior and academic performance as well as their own performance (Greenberg, Brown, and Abenavoli, 2016). A longitudinal study of elementary school teachers found that those experiencing greater stress and more symptoms of depression were less able to create and maintain classroom environments conducive to learning, leading to poorer academic performance among their students (Bottiani, Bradshaw, and Mendelson, 2016).

Contributors to teacher stress may include school factors, such as a lack of leadership on the part of principals and of support from colleagues, poor school climates, poor salaries, and insufficient materials and supplies. The perception of a lack of autonomy, reported by many teachers, may also play a role, as do teachers’ own competencies for managing stress (Greenberg, Brown, and Abenavoli, 2016). When schools provide needed supports and teachers develop the social and emotional competencies required to manage the demands of their work, teachers can better regulate their emotions (Hoglund, Klingle, and Hosan, 2015; McLean and McDonald Connor, 2015). Strategies for reducing teacher stress are discussed in Chapter 4.

One area of growing concern has been the negative effects of out-of-school discipline, such as suspension and expulsion, on the MEB development of young people, especially minority children and youth. African American students are suspended three times more frequently than their white peers, a disparity that begins as early as preschool (U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, 2014). Black preschool children, for example, receive 48 percent of out-of-school suspensions from preschool, although they make up only 29 percent of preschool enrollment; students with disabilities, English learners, and boys also receive harsh discipline at rates that exceed their representation in school populations (U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, 2014).8 Teachers’ implicit racial biases may play a role in such disparities (Girvan et al., 2017). The problem is serious enough to have been termed the “preschool to prison pipeline,” and the trauma for young children of receiving severe punishments has been associated with negative MEB outcomes (Meek and

___________________

8 See https://ocrdata.ed.gov/Downloads/CRDC-School-Discipline-Snapshot.pdf.

Gilliam, 2016). Students who receive school suspensions, for example, are more likely to show later antisocial behavior, such as criminal activity and violence, as well as to experience incarceration and victimization in adulthood (Hemphill et al., 2006; Lamont, 2013; Wolf and Kupchik, 2016).

Foster Care

As noted above, trauma such as child abuse and neglect can have serious and long-lasting effects on a child’s MEB development. Despite being necessary for the safety and well-being of a child, however, the removal of a child from the home can also be devastating and confusing.9 Once children enter foster care, moreover, they may experience prolonged stays and numerous moves, experiences that can have lifelong impacts. Of the 238,230 children who exited foster care nationally in fiscal year 2014, 53 percent had been in care 12 months or longer (Children’s Bureau, 2016). The longer a child is in placement, the greater the likelihood that he will move from one foster placement to another, putting him at increased risk of negative social and emotional outcomes (Sudol, 2009). It has been estimated that 80 percent of young people involved with the child welfare system require mental health intervention and services to address developmental, behavioral, or emotional issues, including complex and secondary trauma (McCue Horwitz et al., 2012; Pecora et al., 2009). The child welfare system has also been critically affected by the ongoing opioid epidemic, which has greatly increased foster care placements and added stress to an overburdened system. In the 5-year period of 2012 to 2016, the number of children in foster care nationally rose by 10 percent, from 397,600 to 437,500 (Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2019).

Young people experiencing frequent moves in foster care face continual disruption of relationships with friends, siblings, and other relatives; coaches, teachers, and classmates; religious leaders; and others. Partly as a result of this disruption, children and youth in foster care have high levels of mental health needs, and those needs often are not being met (Szilagyi et al., 2015; Turney and Wildeman, 2016). Children in foster care also may be given psychotropic medication without proper treatment planning and medication management (Levinson, 2018).

Some state policy makers understand that children and youth in foster care face long-term risks from their exposure to violence, maltreatment, and other adverse experiences, and have pursued opportunities for states to identify and implement strategies for minimizing the long-term consequences of these experiences and reducing the associated costs (Williams-Mbengue, 2016).

___________________

9 Kinship care, in which children are cared for by relatives when their parents are unable to carry out that role, is widely preferred to foster care, in which the state identifies households in which to place children. Kinship care may minimize trauma and have other benefits as well (https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/outofhome/kinship/about), but there is less research on this form of care than on foster care.

Recently, the National Council of State Legislators reviewed state policy and legislative initiatives from 2008 to 2015 to identify areas in which state legislatures have been active. These efforts include convening child and family system leaders, promoting the coordination of mental and physical health care and child welfare, encouraging comprehensive screening and assessment, implementing evidence-based services, and encouraging the use of Medicaid to improve the social and emotional well-being of children in foster care (Williams-Mbengue, 2016).

Societal Influences

A growing body of evidence is revealing the ways in which characteristics of the more distal social environment affect development. These factors include poverty and inequality, discrimination and racism, marketing of unhealthy products, and effects of involvement with the criminal justice system. These more distal influences on MEB development place distinct limits on society’s ability to foster healthy MEB development and prevent MEB health disorders at a population level.

Early childhood is a time of high plasticity that affords opportunities to foster healthy MEB development. Healthy early development (physical, social, emotional, and cognitive) strongly influences a wide range of later outcomes, including mental health, heart disease, literacy and numeracy, criminality, and economic participation across the life span. Health disparities adversely affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health based on their racial or ethnic status; religion; socioeconomic status; gender; age; mental health; cognitive, sensory, or physical disability; sexual orientation or gender identity; geographic location; or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion (Healthy People, 2015). A meta-analysis of nearly 50 studies showed that almost 20 percent of deaths in a single year for people over age 25 were associated with social factors, such as poverty, racial segregation, and low social support (Galea et al., 2011). The antecedents of many of these outcomes are found in the early years of life.

The committee was asked to consider not only the prevention of MEB disorders but also the promotion of healthy MEB development. For this reason, we address the impact of society-level factors on a broad range of undesirable outcomes, including not only MEB disorders, such as depression, antisocial behavior, and drug abuse, but also obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome; academic failure; and other chronic disorders and disabilities that in turn influence MEB development. For example, childhood poverty appears to be a risk factor for a wide variety of psychological and behavioral problems (Yoshikawa, Aber, and Beardslee, 2012), as well as all-cause mortality (Galobardes, Lynch, and Smith, 2008). Changing these outcomes will require higher levels of health promotion at a societal level, including the promotion of childhood well-being.

One important example is the social determinants of health. By one estimate the United States spends $3.5 trillion per year on health care (Centers for Medicare

& Medicaid Services, 2018), which is 18 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (Squires and Anderson, 2015). Health care costs per person in the United States exceed those found in any other member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (Sawyer and Cox, 2018). Yet, this spending does little to address some of the most important factors affecting health: social determinants of well-being such as housing, food insecurity, poverty, and discrimination.

Poverty and Inequality