5

Looking to the Future

To start the second day of the workshop, Arthur Kellerman reminded participants that the workshop’s overall focus is on large-scale disasters that far exceed the resources not only of a single hospital or local government, but even of a big national health system that might have the resources, but needs to network and coordinate with others in the response process. He also noted that an adequate response is built on existing and robust relationships, a workable structure, and confidence that organizations that might compete under normal circumstances will come together and cooperate when a community or entire region is faced with a large-scale disaster. For that reason, successful models more often resemble adaptive networks rather than hierarchical structures. Successful models, said Kellerman, combine the best attributes of individual institutions and communities and of local, state, and federal governments.

He then recounted a discussion he heard the previous day in one of the small groups about what determines a region with regard to forming a regional coalition. In Texas, for example, the regions were defined by looking at where patients self-referred and where physicians sent their patients for referrals. This reminded him of the old adage that the place to put sidewalks on a college campus is to look for the wear marks across the lawn. “Maybe that is a model we need to think about in the future for defining regions,” said Kellerman.

There was a clear recognition from day one of the workshop of the need for regular interactions and drills, with no-notice drills being better than a dress rehearsal-type drill, Kellerman said. Similarly, near-misses and smaller scale events can provide insights of immeasurable value. There was

also discussion that the players involved in responding to a mass casualty event may need to respond given the ongoing evolution of American health care from a primarily hospital-based model to a more disseminated, community-based model with outpatient surgery facilities, urgent care facilities, dialysis centers, and standalone emergency departments.

Kellerman noted that the National Academy of Medicine’s concept of a learning health care system could be applied to the disaster response system. “I rarely use the word ‘research’ in disasters because the public does not understand how you can be doing research when you are trying to save lives and well-being,” he said, “but concurrent evaluation could help us refine and incorporate and systematically get better, just as the joint trauma system did when the militaries were in Iraq and Afghanistan.” The military’s joint trauma system did not do research per se while fighting a war, but it refined, implemented, and adapted based on learnings in the field and became markedly better during the latter half of those conflicts than in the first half, he said. “We can do the same thing with disaster response in this country,” said Kellerman.

One concept that came up, Kellerman summarized, was the need to relax some of the regulatory and legal standards that govern patient privacy, record sharing, and recordkeeping, for example. Another topic of discussion was whether the trauma system is the best model for coalitions, for while it is an appropriate model for some regions or situations, other mass casualty events could require a different model. A third theme Kellerman identified from the first day was that the federal government, including the VA and DoD, can contribute significant capabilities during a large-scale disaster that will enhance the community response.

The second morning’s session featured three panels that addressed various aspects of thinking about the future of the nation’s disaster response system. Open discussions followed each of the three panels. The first panel on best practices was moderated by Skip Skivington from Kaiser Permanente, and included Eileen Bulger from the University of Washington and the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma; James Jeng from the Mount Sinai Healthcare System and the American Burn Association; John Halamka from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; and Gina Piazza from the Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center, the Medical College of Georgia of Augusta University, and the American College of Emergency Physicians’ High-Threat Emergency Casualty Care Task Force.

The second panel, also moderated by Skivington, featured talks from individuals and organizations that are leading change across the field. The panelists were John Auerbach from the Trust for America’s Health; Mitchell Katz from New York City Health and Hospitals; Ana McKee from the Joint Commission; and former Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, Craig Vanderwagen currently of East West Protection.

The third panel, moderated by Jon Krohmer from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, included comments from individuals whose organizations are leading change at the local level. The panelists were Harold Engle from First Texas Cypress Fairbanks Medical Center Hospital; Lewis Kaplan from the University of Pennsylvania; Paul Kivela from the Napa Valley Emergency Medical Group and the American College of Emergency Physicians; J. Brent Myers from ESO Solutions and the National Association of EMS Physicians; and Paul Hinchey from Boulder (Colorado) Community Health.

CULTIVATING BEST PRACTICES

The American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, said Eileen Bulger, is a multispecialty organization of some 3,000 surgeons and surgical subspecialists. It sets the standards for what is required to become a trauma center and then verifies some 500 trauma centers per year. The organization also has a trauma system consultation program and a quality improvement program that engages more than 600 hospitals annually. Bulger explained that a trauma system represents the entire continuum of care for an injured patient, including injury prevention activities. From an acute care standpoint, trauma care begins with bystander intervention, she said, and toward that end, the committee has led the Stop the Bleed campaign that aims to provide civilians with basic bleeding control procedures. They define a trauma system as one that includes a trauma center, a communications system, and a close relationship with emergency medical services agencies. In their definition, care then extends into rehabilitation.

Trauma systems have also served as a model for emergency care for strokes, cardiac care, other time-sensitive medical conditions, and disaster preparedness. The keys to each of these systems are that they require timely and structured cooperation across multiple entities and that they are able to stand up on a daily basis, said Bulger. The trauma system, she said, is geared to deal with the everyday mass casualty events that occur in communities, but the communication and coordination that goes into responding to such events can provide the infrastructure needed to respond to a larger event. “When events get larger, the trauma system is able to surge in a way that can deal with a much larger group of patients, but still in a time-sensitive fashion,” said Bulger. During a mass casualty event, she noted, the trauma system engages both the trauma centers and all of the acute care facilities in a region.

A high-functioning trauma system functions as an integrated learning health care system, said Bulger, who believes that such systems can serve as models for what the nation’s disaster response systems should become. The trauma system is built on a public health approach, and good guidance is

available on how to establish a trauma system (Committee on Trauma and Trauma System Evaluation and Planning Committee, 2008; HRSA, 2006). There are good data, she noted, that show trauma systems make a difference in terms of reducing mortality (Cudnik et al., 2009; MacKenzie et al., 2006). One recent study from Arkansas showed a 48 percent reduction in preventable deaths after implementation of a statewide trauma system (Maxson et al., 2017).

The Committee on Trauma advocates for an inclusive system in which all hospitals have to care for injured patients in a disaster setting, designed to get the right patients to the right place at the right time. “We want to match the patient to an appropriate center, and that means we have triage strategies, transfer strategies, and transfer agreements that make it clear how a patient should move through a trauma system,” said Bulger. These agreements often cross health care systems, which requires establishing good relationships and communication strategies among those health care systems before a disaster strikes.

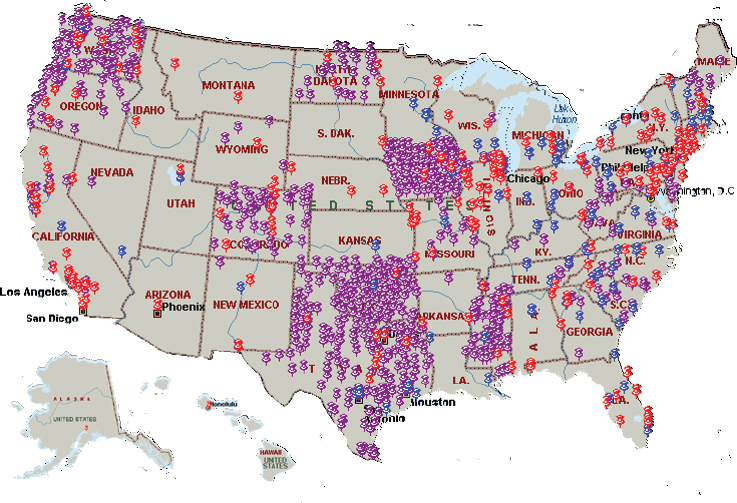

The committee also believes it is important to designate and distribute trauma centers based on the needs of the population. The goal, said Bulger, is regionalization rather than centralization, which requires defining a region based on patient flow and a network of hospitals that work together. She noted that states have taken varying approaches to creating a trauma system, with some having many trauma centers and others taking a more parsimonious approach (see Figure 5-1). Texas and Washington State, for example, take an inclusive approach that engages centers statewide to be involved in the system and have the appropriate training, infrastructure, and knowledge to move patients through the system. What this inclusivity accomplishes is that patients in rural areas will be able to reach a trauma center, be stabilized, and then transported if necessary to a higher level trauma center for further care. There are data, said Bulger, that correlate the structure of a trauma system to outcome and reveal marked variability in injury mortality by population based on system design (Brown et al., 2017).

In 2016, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine issued a report calling for a national trauma care system that integrates military and civilian systems and optimizes system design (NASEM, 2016). The vision presented in this report, said Bulger, is to develop a system in which the civilian and military trauma systems share aims, infrastructure, system design, data, best practices, and personnel. She noted that the civilian system certainly benefits from the lessons the military learns in a conflict, but the military can maintain readiness by training with the civilian system when not engaged in a war. Together, the two systems working collaboratively would make the nation more resilient in the face of a disaster.

The Committee on Trauma has developed a list of the 10 minimum requirements for a trauma system that it is vetting with outside stakehold-

SOURCE: Presentation by Bulger, March 21, 2018.

ers (see Box 5-1). Bulger said that in the committee’s view, the best strategy for trauma system development is to have minimum requirements set at the federal level that are then implemented at the regional and local levels. She noted that there is some literature on the impact of trauma systems on disaster preparedness, including a 2014 systematic review (Bachman et al., 2014). This review identified four key domains of a trauma system that affects disaster preparedness: communication, triage, transport, and training. STRAC’s approach illustrates how an entire arm of disaster preparedness can be built from the trauma council structure, said Bulger.

In Bulger’s opinion, trauma systems are the backbone for disaster planning because they offer a preexisting multidisciplinary governance structure, integration across health care systems, integration with EMS and air transport, established communication channels, and patient tracking strategies. In Washington State, for example, she can go online and see the status of every hospital in the state, get a picture of their bed status, and see changes in that status in real time.

In her final comments, Bulger listed the next steps for developing a solution to the nation’s disaster preparedness deficiencies. The first step should be to bring to fruition the national trauma action plan called for in

the National Academies report she mentioned earlier (NASEM, 2016). Doing so would require federal leadership to establish minimal trauma system standards and regional governance and implementation. There then needs to be support for trauma system development as part of disaster preparedness funding, something that Bulger said has been lacking since 2005, and optimized engagement between existing trauma systems and health care coalitions. She also explained that some mechanism is needed to facilitate the movement of licensed health care providers across state lines during a disaster, and trauma centers need to stand up and provide support to non-trauma centers, particularly during mass shooting events. She noted that the House of Representatives has passed the Mission Zero Act, which would provide funding to support the integration of military teams into civilian centers, and this bill is now awaiting approval by the Senate. Finally, the nation needs to support strategies for rapid assessment and debriefing after a major event to provide the lessons that inform improvement.

Addressing Strategic Bottlenecks

In his presentation, James Jeng pointed out that the burn care community represents one of several strategic bottlenecks in the national system response to mass casualties and other calamities. “We are a supporting actor, but the problem is there is not enough of us,” he said. He reported that currently, there are only 1,800 burn beds and 250 active burn surgeons in the United States. “We cannot make more burn units or more burn doctors because it is economically not feasible in peace time, but in times of crisis, we need to be able to surge,” said Jeng. The same can be said, he added, of orthopedic trauma, neurological trauma, radiation trauma, and other subspecialists where the economics do not enable the development of surge capacity. He called for the nation to develop a cogent strategy to deal with these bottlenecks, which he said are the weak links in the nation’s trauma care system.

When discussing threats to public health and national security, burn care needs a place at the table to cultivate innovation and improve best practices, said Jeng. He noted that over the past 8 years, the American burn community has developed a rewarding partnership with ASPR as a result of Congress mandating that money be spent on preparing and amplifying the nation’s burn response capabilities. Today, whenever there is a mass casualty event, or even when the President is speaking to a large crowd, ASPR and the Office of Emergency Management are in close contact with the American burn community. In fact, if ASPR and other federal agencies had not developed what Jeng called a symbiotic relationship with the U.S. burn care system, the nation would have no ability at all to amplify the burn care response in the event of a mass casualty. “It is this far-sighted thinking on the part of the U.S. government to help us come up with innovative ways to amplify to scale in the face of [a] 200, 2,000, or 20,000 mass burn casualty that allows me to sleep better at night,” said Jeng. He added that in an explosion, roughly 25 percent of the trauma victims will have burns that will be life threatening without specialty burn care.

Jeng said that the burn care community recognizes its capacity is limited and that it will be on its own for the first 96 hours or so after a disaster. As a result, the burn community has developed its own mutually supportive, self-organizing network in which the members know each other’s cell phone numbers and have an implicit understanding that they will only have each other to turn to for help in the first 3 to 4 days of a major crisis. He also noted that ASPR, through BARDA, has committed more than $500 million to private-sector research on burns, including the development of spray-on skin, a pineapple-based cream that melts away second-degree burn tissue before it becomes a full-thickness burn, and stem cells derived from adipose tissue. These technologies, which he predicted will be in the market soon,

represent ways to amplify a fixed burn care infrastructure and give the burn care community hope that it can respond to a situation with 2,000 or even 20,000 burn victims.

One of Jeng’s regrets is that the subspecialties that represent bottlenecks are siloed, so that each small community is doing its own lobbying for funds and developing its own protocols. These silos, he said, have the opposite effect of muscle memory when it comes to communication and coordination. “We need to start breaking down silos so that we are not islands of expertise but can be synergistic,” said Jeng. Another key challenge he sees is getting these small communities to plan and prepare to foster on-demand scalability of strategic bottleneck supporting actors.

Regarding key elements that could be used to improve situational awareness of public- and private-sector capacity and capabilities to respond to disasters, Jeng said the burn community continually feeds information to the federal government about bed availability. Unfortunately, approximately 80 percent of the nation’s burn beds are occupied on a typical day, and even moving some patients to normal beds would open only 500 to 600 burn beds in a crisis. He said the burn community is working with ASPR’s Office of Emergency Management to feed detailed situational awareness data into ASPR’s online geographical information system. As a final comment, he said the U.S. Army’s Institute of Surgical Research has an irreplaceable role to play in the event of a mass casualty disaster that involves thousands of burn victims.

Information Technology in Times of Disaster

At 11:45 AM on November 2, 2002, a regional, integrated information network developed by a number of hospitals in the Boston area collapsed (Berinato, 2003; Halamka, 2008). “The hospitals of 2002 became the hospitals of 1902,” said John Halamka. “We could not order anything, medications or labs. We could not view radiology studies. All of that automation that we depended on was gone.” Within minutes of the system crashing, the 11 hospitals in the CareGroup network began running handwritten notes with lab results between hospital units, using telephones and every other non-Internet-based communication modality imaginable to keep their patients safe. The incident lasted for 3 days, and it provided a glimpse of what could happen if an electromagnetic pulse from a nuclear weapon took out all of the nation’s electronics.

Halamka also recounted what happened in the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013, a regional incident that required care coordination, communication, and situational awareness. The mayor, however, ordered the region’s cell phone network to be shut down because of the fear that the bombs were being set off by cell phone. “No cell phone com-

munication was possible with any first responder,” said Halamka, “and we had to move to alpha text paging, a 1970s technology, but a highly resilient technology in the absence of a cell phone network.”

Another issue that arose in the bombing’s aftermath concerned the security of victim and perpetrator records. Many people who came in with traumatic injuries needed pictures of their injuries for their medical records, and the surgeons used their smartphones to take pictures. “Imagine in those first few critical hours, potentially we had perpetrator and victim photography in the cloud, not where you would want it to be,” said Halamka. “Since then, we have developed apps, secure photo repositories, and other things.”

One year later, on the eve of Patriots’ Day, the chief information officer of Children’s Hospital received a message from the hacktivist group Anonymous informing him that they were going to take down the hospital’s network as retribution for the hospital making one patient a ward of the hospital. The problem, said Halamka, was that Anonymous did not know the Internet address of Children’s Hospital, so it launched an attack on an Internet subnet that included Harvard University, Massachusetts General, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dana-Farber, Joslin, Beth Israel Deaconess, and Children’s. At 2 AM on the eve of the marathon, every hospital in Boston lost the ability to communicate and coordinate care because the Internet of the entire region was flooded with a massive denial of service attack. At 2:10 AM, Halamka had every chief information officer on the phone. By 6 AM the network was back in operation thanks to Halamka writing a $60,000 check at 2:30 AM to a large technology company that offloaded the entire network.

Halamka and his colleagues learned several important lessons from these three incidents. One lesson was to use emerging technologies such as the cloud to increase resilience. Today, for example, seven petabytes of patient-identified information of all health care in Boston are stored in the Amazon cloud, a distributed, worldwide network with 50,000 employees. “In a mass casualty, who is going to be more resilient, a regional health care delivery system or Amazon?” asked Halamka. “Our answer is Amazon.” Today, his health care system has contracts with a wide range of technology companies to provide cloud, mobile, interoperability, and machine-learning technologies. Recently, Halamka has been working with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation on a project in Africa that uses a blockchain mechanism to store data with great resiliency despite working in a region with poor infrastructure, unstable power, and governments that are not always honest. “You think about these kinds of emerging technologies that will give us as a health care system much more resiliency than any local actor,” said Halamka.

Communication and cooperation has been a repeated theme during the

workshop, and those are hallmarks of the network of health care system chief information officers in the Boston region. Halamka said they not only have each other on speed dial on their cell phones, but they plan together and drill together. They also work together on educating their workforces on downtime procedures, privacy imperatives, the latest malware and ransomware, and preparation for physical disasters. He believes the role of the private sector is increasingly important in the area of building cloud capacity and innovation and developing policies and protections so these emerging technologies can be used wisely. He pointed out that the Office for Civil Rights has been a great partner in figuring out how to keep data private and safe while moving it to these new, innovative platforms.

One of his jobs as an endowed chair of innovation at Harvard is to spread the lessons learned from incidents such as the three he discussed. In his talks around the country, he stresses that these new technologies are good enough and safe enough to serve as risk mitigators and tries to reassure health system administrators who are afraid of the cloud. His dream is that the early adopters of these technologies will join his efforts to convince everyone in health care that these technologies mitigate rather than increase risk.

High-Threat Incidents

Although a high-threat incident can describe any event that involves an ongoing physical threat to victims and responders, Piazza said she would be referring to violent criminal and terrorist-related incidents such as bombings, mass shootings, vehicle-borne attacks, and complex coordinated attacks. Such incidents disrupt public health, safety, and security. As an example, she described a 2018 event involving an active shooter. At the time, influenza cases were overwhelming emergency departments and all of her hospital’s beds were full, as were those of every other hospital in the area. When she received the active shooter alert that indicated there was a strong possibility the shooter would enter her building with the intent to kill, her first thoughts were that her institution was not ready, and the region had insufficient capacity to handle mass casualties. “If we cannot do this well on a regular day, what can we expect on an exceptional day?” she asked. “With more than 50 years of attention to trauma and emergency care in a crisis, we remain a populace, a health care system, and a nation insufficiently prepared to deal with high-threat incidents.”

In her opinion, the best opportunity to deal with such an event is to prevent it before it happens, but aside from that, the next best opportunity to intervene in the trauma chain of survival rests with empowered civilians. “The truest first responder is the closest able-bodied person to the significantly wounded casualty, and it would certainly behoove us as a

nation to ensure that all able citizens know basic trauma first aid and how to respond in a high-threat incident,” said Piazza, echoing Bulger’s earlier recommendation.

High-threat incident response is complex and involves multiple disciplines acting under extreme stress, said Piazza. Unfortunately, the perpetrators of these events have shown the ability to learn the system’s response tactics and evolve their threats to achieve maximum harm. As a result, the emergency response system must step up its efforts to learn from these events and adjust its tactics, medical interventions, transportation modalities, hospital preparations, first responder actions, and recovery elements to minimize mortality and also minimize morbidity to survivors, first responders, and the affected community and the nation that grieves along with the affected communities. One challenge to such a learning emergency response system is that there is no standardized methodology for gathering data around these events or a repository in which to place data for ongoing analysis.

To Piazza, DoD’s work on reducing battlefield deaths represents a best practice for a learning health care system. By creating its joint trauma registry and populating it with data from nearly all casualties, the military was able to determine wounding patterns and improve both countermeasures and medical response protocols, generating best practice guidelines in the process. Once implemented, she said, DoD continued to gather data, study it, and refine those best practice guidelines. “This is superior to what we have been able to do thus far around high-threat incidents given our limitations as a disconnected response in emergency care environment in the United States,” said Piazza. “Instead of learning by anecdote, news media reports, late and sometime redacted after-action reports and papers published with constraints, there might be a better way forward.”

Looking at the public–private partnership around high-threat incidents reveals some barriers and possible levers, said Piazza. Mitigation remains challenging, she said, with breakdowns in communities and social relationships, insufficient mental health care services, and evolving criminal and terrorist threats. In her opinion, there is tremendous room for private-sector engagement in fostering community wellness and preparedness, though this would likely require new payment structures and aligning financial incentives around wellness, preparedness, and surge capacity. “The private sector and the general public could demand these changes from government,” she said.

There is also room for a partnership with the public around preparedness. She cited a 1966 National Academies report that recommended that all U.S. school children past fifth grade should receive first aid training (NAS and NRC, 1966). “A prepared, educated, and empowered populous is a defense against high-threat incidents in the vein of see something, say

something, and a force multiplier in response to high-threat incidents, i.e., do something,” said Piazza. In her view, schools, community centers, public safety, hospitals, and businesses should offer such training, and insurance companies might consider lowering premiums for individuals who receive such training. Similarly, if true preparedness and surge capacity were part of quality measures or CMS conditions for participation, hospitals might be more apt to offer overtime pay for full engagement in full-scale exercises. As Piazza noted, readiness should not be an unfunded mandate and not intermittently funded by finite grants.

One best practice she would like to see adopted is to study these events and the response to them from the point of wounds through recovery. Such studies should become routine and include efforts to understand injury patterns and why some people live and others die. They should include studies of transportation methods and medical interventions by provider type. “We need to gather information as close to real time as possible and rapidly disseminate the lessons learned so that we are all better prepared for the next event,” said Piazza. She also called for establishing a single entity with the authority to gather, store, and disseminate these data.

Building on the work of a number of colleagues, the FBI’s victims services supply teams, and the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), Piazza’s task force at the American College of Emergency Physicians suggests developing rapidly deployable multidisciplinary teams of subject-matter experts with the ability to gather discipline- and casualty-specific qualitative and quantitative data and develop best practices. Establishing such teams would likely require legislation and is another area, she said, where the public, a unified house of medicine, and public safety associations could bring their weight to bear to see such legislation passed.

In closing, Piazza asked how the nation can cultivate innovation and develop best practices for high-threat emergencies. She answered her own question by stating that the nation can develop an achievable strategic plan based on 50-plus years of excellent ideas, proper incentives, and objectives that are met and sustained. “We can employ a whole-community approach, as has been discussed over the past 2 days, and we can provide our researchers, educators, and innovators sufficient time, funding, authority, and opportunity for competition so as to foster success,” she added. In addition, the nation can create a database and NTSB-style teams to facilitate learning and improvement and develop secure methodology for sharing lessons learned as rapidly as possible.

DISCUSSION

Lynne Bergero from the Joint Commission asked if the panelists had seen examples where training civilians to be prepared to respond has taken

hold and been scaled. She explained that there are grassroots organizations in Chicago, where the Joint Commission is located, that have taken it upon themselves to undergo Red Cross training in first aid and that there are nascent community emergency response teams. She wondered, then, if it would be possible to ramp up this kind of grassroots training activity and connect it to other efforts such as the Stop the Bleed campaign.

Bulger replied that Stop the Bleed is focused on minimizing the most common cause of preventable death in these events. It consists of teaching very basic skills, such as how to pack a wound and hold pressure and how to apply a tourniquet. This campaign has two parts: public education that aims to train every citizen in the country, and having the necessary equipment in place similar to the way automatic external defibrillators are widely available. This program, which was launched by the Obama administration, has taken off under the leadership of the American College of Surgeons. Currently, some 150,000 people have been trained, and there are now 16,000 registered instructors. In her opinion, Stop the Bleed should be integrated into school systems and become a requirement for graduation, which is already the case in Washington State for cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Piazza said the American College of Emergency Physicians is also a supporter of Stop the Bleed. She noted that the federal government has started the “Be the help until help arrives” campaign, and she is working on a follow-on project called First Responder On-Scene Training. Thomas Kirsch commented that the National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health is working with the Red Cross to roll out Stop the Bleed as part of its first aid training in the next few months. The Red Cross believes it can train 20 million people.

Piazza added that efforts like these to train law enforcement officers to provide initial medical care were resisted when she first started working with law enforcement, but that is no longer the case. Now, an increasing number of police officers are going into medic mode, as she called it, once the threat is neutralized, and then into transport mode to get patients to the hospital quickly. She said she would like to see more medical societies become involved in such efforts. “Imagine if every trauma surgeon and every emergency physician in this country taught one class to one group, how many people would be educated?” she said. “I truly believe that a nation prepared is going to be what allows us to have better outcomes in these events.”

Bulger said that while training bystanders she realized this was not in the scope of practice for EMS. Her organization worked to change the scope of practice for EMS this year, and all EMS training now includes wound packing. For her, having as many partnerships as possible that are

all saying the same thing will get the message out about the importance of being prepared to be a responder.

Kaplan asked Bulger to comment on the idea of using the trauma network as a framework for pandemic response. Bulger replied that her organization agrees with the criticism regarding using the trauma system as a backbone because not everything is trauma related. Having said that, the trauma system can be a model for how to set up relationships, bring a multidisciplinary group together that crosses health system boundaries, communicate regularly, and establish best practices on communication and moving patients through a system. To respond to pandemics, which are going to be much bigger events and involve more hospitals, the challenge is to build out that framework on a larger scale.

Monique Mansoura from the MITRE Corporation remarked that cyber security and information technology experts are not at the table with disaster preparedness leaders, and she asked Halamka for his ideas on how these cyber capabilities should be integrated into the broader preparedness domain. Halamka replied that cyber security is foundational to everything his health system does, noting that Harvard and its networks are attacked every 7 seconds, 24 hours per day, 7 days per week. These attacks are no longer from Massachusetts Institute of Technology students, which they used to be, but from organized crime, nation-sponsored cyber terrorists, and hacktivists who want to corrupt and damage data and steal identities. As a result, cyber security is at the table for every disaster planning activity his institution holds.

John Dreyzehner asked the panelists for ideas on how to deal with the silo problem that Jeng described. Jeng replied that while everyone complains about being constrained by limited budgets, breaking down silos is free and is a matter of collective will to not be beholden to turf wars. “Everybody in this room needs to espouse the concept [of] one team, one fight,” he said. Bulger added that one symptom of having silos is the difficulty in combining registries with burn data, electronic health records, trauma quality improvement databases, autopsy data, and other sources of valuable information. The American College of Emergency Physicians has a big initiative to figure out how to assemble those data during a large-scale event in a way that is quick, comprehensive, and does not compromise law enforcement investigations to enable learning and improvement. She noted that there are no data showing how many people Stop the Bleed has saved, something that would be good to know.

To end the discussion period, Brendan Carr made a plea for the major professional societies to create a consortium and work together collaboratively to develop a list of next steps, a shared vision for what the federal government can do to further the nation’s preparedness and response ca-

pabilities. “I hope I am not overstepping what can be said as a government official, but it would be helpful to hear a shared vision,” said Carr.

LEADING CHANGE ACROSS THE FIELD

Skip Skivington opened the second panel in this session by noting that change is at the heart of what must happen to improve the nation’s disaster preparedness and response, yet change is hard for both individuals and balkanized organizations. Nevertheless, he said, the four panelists all had experiences with fomenting change in their organizations. Craig Vanderwagen, the first panelist to speak, was the original Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response. He reminded participants that ASPR was stood up in 2006 after the passage of the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act, and it occurred partially in response to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon; the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada that raised the specter of a looming pandemic; and the 2004 tsunami that devastated Indonesia, and Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. The Act, said Vanderwagen, effectively took into consideration ASPR’s potential responsibilities in leading all federal assets in public health and medical disasters, including the formation of BARDA and the development of medical countermeasures for 15 threats identified by DHS.

The first problem he and his team faced in ASPR’s early days was changing the culture of HHS, ASPR’s parent agency. At the time, HHS was not an action-oriented organization, and its culture was dominated by two groups: the subject-matter experts, who generated the necessary evidence base but never had enough data to make a decision, and the contracting officials and lawyers, who in general believed, as Vanderwagen put it, that “you cannot get there from here.” His approach to developing an action bias culture was to identify ASPR’s mission and ensure that each person in the organization understood that mission, which was to save lives, reduce the burden of suffering, and speed recovery. “We managed and led around those objectives, and I say ‘we’ because it was a team effort,” Vanderwagen explained.

ASPR’s focus from the start was on facilitating local capacity building by incentivizing and nurturing the ability of local communities to own their outcomes in an effective way. He told how he grew up on a reservation in New Mexico, where his father’s family had lived since the 1880s, and one lesson he learned living in a tribal community is that the community’s survival and perpetuation of its culture and language are more important than the individual person. “We wanted to bring that kind of commitment to tribal survival to the communities we serve,” said Vanderwagen. He also explained that the task of making BARDA an effective tool demanded that

ASPR engage with the private sector as a trusted and respected partner in a public health emergency countermeasure enterprise. This, too, required culture change, for the prevailing attitude in HHS at the time was one that undervalued and mistrusted the private sector.

Mitchell Katz explained that the New York City hospital system that he runs includes 11 public hospitals operating in the same areas as many private hospitals. As a result, he thinks a great deal about how private- and public-sector entities can work together. The best successes he has seen occur during mass casualty events, when EMS is in charge of transporting those who have been hurt to the hospitals best able to care for specific injuries.

The times when public- and private-sector entities do not work well, he said, is when one of the hospitals in a system goes down and patients have to be moved, along with their medical records, and clinicians need to work in a new hospital. The reason why that situation is so difficult, said Katz, is because nobody is in charge. “If I want 20 of my doctors to be able to cross the street and work at NYU [New York University], is that my responsibility to make that happen or NYU’s responsibility?” asked Katz. “Who owns the medical records? Do I follow all of the discharge procedures as set in law for sending [medical personnel] in the midst of an emergency?” His answer to the last question was “presumably,” but in none of the three cities where he has worked—New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco—was there much in the way of planning or exercises that worked out how the public and private sectors worked together in that situation.

In New York City, the 11 hospitals Katz oversees work together among themselves, and he said he is sure the private systems do as well, but working independently of one another is not going to help if one hospital is knocked out during a crisis. He agreed with Jeng that collaboration is free, and he noted that money should not be a problem anyway given that the nation spends 18 percent of its gross domestic product on health care. “It is hard to say that money is the major reason we cannot respond in an emergency,” said Katz.

One issue he would like to see addressed involved defining what an emergency is. To illustrate the problem, he recalled how New York City faced a shortage of pediatric Tamiflu, which commercial pharmacies ran out of in March 2018 during the influenza outbreak. He wanted to start providing this drug to his system’s patients in the hospital and to waive the co-pay, reflecting the fact that many of the patients his system treats cannot afford the co-pay. His lawyers said he could not do that because the co-pay is contractual and is about decreasing usage. In retrospect, Katz suspects that if he had tried to argue that this was an emergency and that this contractual obligation should be waived, the lawyers would have pushed back that it was just the flu season and not a real emergency.

Katz noted that one of the most difficult things that happened during Hurricane Sandy had to do with credentialing and privileging doctors who could no longer work in their home hospitals. Normally, credentialing takes 2 months, he explained. Developing procedures that would shortcut that process during an emergency is something that should be worked out ahead of time. “We could decide what constitutes an emergency, and we could decide under these circumstances there are other ways of doing things,” said Katz.

After noting that he agreed with an earlier comment that regions define themselves, he said that one lesson he has learned from every mass casualty event is the importance of having a well-defined leadership structure. Having such a structure is not about control, but rather is about making sure that things happen in an orderly manner. In closing, Katz said that as far as he knows, the three cities where he has worked do not have a leadership structure that would know how to respond to an emergency that included both the public and private sectors, although there is such a structure within each of those sectors.

Disaster preparedness and response, said Ana McKee, are critical to the mission of the Joint Commission, which she explained is the largest and oldest accreditor of health care in the United States. To the Joint Commission, emergency preparedness is about quality and patient safety, which puts it firmly in the organization’s bailiwick. As an example of how the Joint Commission can be a resource in the national preparedness effort, McKee noted that when Ebola threatened U.S. hospitals, her organization knew that the hand hygiene rate of 40 to 50 percent across its accredited hospitals was insufficient to deal with that threat. The Joint Commission also knew from its data that the compliance rate regarding personal protective equipment was also low. If necessary, the Joint Commission could have sounded an alarm about this situation. “In many ways,” said McKee, “we know what our organizations are capable of and ready to do.”

The Joint Commission has established standards for emergency preparedness and was the first accrediting organization to require health care systems to plan and conduct drills for emergencies. McKee said these standards are excellent for being prepared to deal with a catastrophe within the walls of a hospital, and good if the disaster happens within a community, such as in a mass casualty bus accident. Where the Joint Commission, and the nation as a whole, needs to improve is in setting standards for regional disasters and for situations with massive infrastructure damage. In her opinion, a national leader with responsibility and accountability for pulling private, public, and government organizations together is needed to achieve the highest level of regional preparedness. Otherwise, she said, “the silos will kill us the next time something devastating happens.”

McKee explained that the Joint Commission coordinates a lessons

learned conference after every event that occurs in one of its accredited organizations. Those lessons are then put on its website and are available to everyone. The Joint Commission, McKee added, puts its learnings in publications and also goes on the road to train and educate its accredited organizations based on those learnings. For example, one of the lessons that came from leadership of Loma Linda University Health, which managed the response to the 2015 San Bernardino shootings, was the importance of managing an anxious workforce, something for which they had never trained. McKee said future standards will have to include something that will help leaders prepare for dealing with clinicians who are worried about their families during a disaster.

Along those lines, one lesson learned from Puerto Rico in the 2017 hurricane season was the need to take in families and their pets and to have the supplies on hand to have that capability. Other lessons the Joint Commission has learned from its organizations is that social media can play a vital role during an emergency, that a multidisciplinary approach to readiness is helpful, and that it is critical to shift from a hospital-centric approach to preparedness and response. In Puerto Rico, for example, a hospital learned how to use social media to find diesel fuel when the distribution system was destroyed.

In thinking about how to move forward, McKee said she is concerned about the capabilities of health system leadership. “What are the minimal competencies that a chief executive officer of a health system needs to have on preparedness?” she asked. “We do not speak about that.” Nonetheless, that leadership will have to take charge of the organizational changes needed to improve preparedness. She is optimistic, though, that the standards and expectations that are being introduced to hospitals will produce the necessary change.

Commenting from his experience as the Boston health commissioner during 9/11, as the Massachusetts health commissioner during the H1N1 influenza outbreak, and at CDC when it was grappling with Ebola and Zika, John Auerbach offered five observations to the workshop. The first was that the public health sector is the key to preparedness and response. Public health is evolving, he said, to be more strategic and to bring together representatives of different sectors to deal with a wide variety of issues, but it should include emergency preparedness in its mission. Public health is well equipped to bring diverse sectors together, something that several speakers mentioned during the workshop.

Auerbach’s second observation was that government resources are decreasing at a time when the number of large-scale emergencies is increasing. In 2017, for example, there were 16 emergencies that each cost more than $1 billion, yet hospital funding is 50 percent lower than it was several years ago and funding for public health is a third of what it once was, he noted.

Reauthorizing the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act will be a key to increasing preparedness funding. Reauthorization should include a preapproved emergency preparedness fund for public health, similar to what the Federal Emergency Management Agency already has. The lack of such preapproved funds cost lives during both the Zika and Ebola outbreaks. “Lives were lost because we waited too long for Congress to pass the emergency funds that were needed to respond,” Auerbach said.

His third observation was that it is important to think about the full spectrum of the public’s health care needs beyond the walls of the hospital. Two areas that are frequently overlooked, he said, are behavioral health and long-term care. “From my experience in major emergencies, the most pressing issues that we experience are anxiety, misinformation, and the trauma that the public experiences, and we have to think about how to have the kind of services that include a basic service for anxious parents or family members as well as the ability to screen for people for whom that level of behavioral health issues is more serious,” said Auerbach. During the hurricane season, for example, people in recovery who were in shelters were unable to continue to receive their substance abuse treatments, which became a problem. Regarding long-term care, he said the experience in recent regional disasters has been that the nation is not well prepared to evacuate nursing homes and long-term care facilities that are forced to close.

Auerbach’s fourth point was that the focus is too often on the acute phase of an emergency, with little attention paid to the postemergency phase. He has heard from those who have gone through emergency situations that public attention often fades after the acute phase, and sometimes resources go away too, while people are still grappling with significant health and other problems such as trauma. His final observation is the importance of dealing with the social determinants of health, including poverty, the consequences of discrimination, social isolation, and challenges related to language skills. “What we have seen is if we do not pay attention to those, the most vulnerable populations often are the ones who have significant social and economic issues in their lives that make them less likely to know about what the response should be and less likely to have access to the services,” said Auerbach.

Public health, he said, can play a key role in thinking about the specialized services that are needed to recognize the elevated risk and vulnerability of certain populations. In Boston after 9/11, for example, his office awarded contracts to train influential residents in subsidized housing on how to work with their fellow residents on pre-emergency planning. During the H1N1 outbreak, his office monitored who was getting vaccinated and noted that people who did not speak English were less likely to be vaccinated even though they were experiencing a higher level of risk of complication and death. His office was able to work with CDC to redirect funds to special-

ized community-based organizations that worked with those populations to get them vaccinated. “That required having a sensitivity and an ability to monitor whether those populations were in fact at an elevated risk and not seeking the services that were available to members of the public,” said Auerbach.

DISCUSSION

Jeng started the discussion by coining a phrase—crisis standards for health care regulation—that he proposed using to get traction with both the Executive branch and Congress to reduce the regulatory burdens that lead to “we cannot do that” and the challenges of moving personnel across state lines during a regional disaster. Vanderwagen thanked Jeng for that suggestion and noted that the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Reauthorization Act offers an opportunity to develop legislative language that would be useful to this community. He encouraged workshop participants to think about possible legislative language that would highlight an area of need and enable the federal government to support local initiatives, rather than creating a structured regulatory environment.

Katz agreed with Jeng that the goal should be to have crisis standards, and he emphasized that the purpose was not to waive standards, but to have a separate set of standards that are appropriate for a declared emergency. He asked Vanderwagen if it would be possible to have that type of language inserted into legislation. Vanderwagen suggested developing a framework that would enable states to address legal, ethical, and medical issues relevant to local laws and make their own decisions, rather than forcing them into a strict regulatory structure. For example, he is working with Alaska to identify laws that are inhibitory and put ethical constraints on what may or may not be appropriate in a crisis environment.

Arthur Kellerman said that in addition to crisis standards, he believes there needs to be a focused approach to educating leaders who can lead in crisis, who can make decisions without perfect information, who can act without worrying about legal or regulatory consequences down the road, and who can work collaboratively and communicate with their employees and the public. Vanderwagen said one approach would be to put potential leaders in a situation where they have the opportunity to lead, to fail, and also to succeed.

Katz said that in his experience, physicians, nurses, and other clinical staff know what to do and focus on the right things, but the general bureaucracy tends not to allow it. He noted that there have been several times in his career where he decided that his staff would do something because it was right for the public and staff replied that they were worried they might get arrested or sued for doing it. His response was to say, “blame me.” In

fact, he has written letters ordering people to do things so that they could have proof that he ordered them to take a particular action during an emergency situation. “Sometimes, even if you are leading, that does not mean that everybody is willing to be certain that your endorsement will cover them if something bad were to happen,” said Katz. Auerbach added that in his experience, getting support from an elected official is helpful in that situation. He also said that having high-level exercises and tabletop exercises that involve those who may called on to understand when those tough decisions need to be made can help lay the basis for a rapid decision later.

Harold Engle agreed with McKee that taking care of a hospital staff’s family members was a major concern during Hurricane Harvey. Another issue that came up then was that many hospitals did not want to declare an emergency until the hurricane actually struck so that they would not have to pay overtime in case the hurricane skirted the region. In his opinion, there is an opportunity to mandate that health care professionals come in to work during an emergency with the caveat that their families would be cared for, noting that clinicians who are worried about their families would be less able to focus on taking care of their patients.

John Dreyzehner commented on the current practice for vaccination that is based on an opt-in framework where parents have to approve of their children receiving a flu shot, even during a pandemic situation. His concern is that this framework may make it hard to provide a medical countermeasure to the most vulnerable members of the nation’s population and he wondered if an opt-out framework for medical countermeasures should be included in a crisis standard-of-care regulation.

Ronald Stewart raised the issue of recommending to the President that the nation needs a national trauma system to deal with the fact that 63,000 Americans, or 175 per day, die from violence every year. Brendan Carr, with the last comment of the discussion period, wondered if there should be a Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise equivalent developed for the private-sector delivery system and private health care insurance sector.

LEADING CHANGE AT THE LOCAL LEVEL

In Houston, which has a dense population, hurricanes and flash floods are always a concern along with hazardous material spills, terrorism, and public health emergencies, said Engle. To prepare for such potential disruptions, he and his colleagues look at their institutions’ hazard vulnerability assessments and their emergency operations plan, particularly after events occur. They also have 96-hour memoranda of operations in place to handle things internally before having to look for external resources. Engle explained that a hazard vulnerability assessment is done generally

at the hospital level. It looks at a wide range of possible events that could occur and does a risk stratification based on how prepared the institution is to respond effectively to those events, how likely the event is to happen, and how many resources the institution can commit to the response. Its purpose, he said, is to prioritize the events for which an institution needs to prepare. He noted that he would like to see more regional involvement in these assessments so that the institutions in a region can work together more efficiently.

Engle’s institution, First Texas Hospital, is rather small, but it has 20 satellite emergency departments around Houston that, in total, typically see 8,000 to 10,000 patients per month. During Hurricane Harvey, 18 of those 20 satellite facilities continued to operate at a volume 30 percent above normal. During the hurricane, many larger hospital systems closed their satellite emergency departments out of concern that they would have a patient who could not be transferred to a more appropriate facility. As a result, area EMS, which usually does not transport patients to freestanding emergency departments, started bringing patients to his system’s facilities.

One tool that Eagle thought was particularly useful during Hurricane Harvey was SETRAC’s EMResource, a Web-based tool that not only enables every health care facility in the region to post its capacity and how many patients it can take, but also make requests for needed supplies. Engle noted that SETRAC conducts tabletop exercises and drills that include home health, nursing homes, and dialysis centers. One thing that helped with Houston’s response during the hurricane was that it never lost communication capabilities, but he is concerned that there is little redundancy in the system.

Regarding staffing, Engle said it is one thing to mandate that staff remain at a facility throughout an emergency, but there need to be provisions to have replacements after 36 hours. “You do not have replacements unless you call a disaster early enough and you do not call an emergency soon enough because your hospital does not want to pay for everyone to be at work,” he said. During Hurricane Harvey, for example, his institution did not call the emergency early enough and some staff had to keep working for very long periods of time. Collaboration, as had already been mentioned, was critical for getting patients to safety during Hurricane Harvey. He, too, called for health care systems to have provisions to take care of family members of staff who have to work during an emergency.

One challenge with collaboration is when systems overcommit and overpromise and therefore are unable to collaborate during an emergency. Engle suggested that it might be useful to provide a summary reimbursement for unfunded care during a disaster, which he acknowledged would be expensive, but might encourage more collaboration. Other incentives might be to provide reimbursement based on a type of care scale or to provide tax

breaks commensurate with the amount of unfunded care. Another incentive for local systems might be a disaster preparedness certification they could use in their branding. He also suggested that CMS could penalize systems that do not fulfill certain obligations and that the Joint Commission’s standards could be tougher.

The Society of Critical Care Medicine has developed a disaster management plan designed to leverage member resources, said Kaplan. He noted that professional societies such as this one, which encompasses practitioners from several subspecialties, can be a valuable partner that regions and the federal government can call on during a large-scale disaster. During the crisis in Puerto Rico, the organization had to take a different approach because it could not get its members into the country. Instead, members gathered in Chicago, created an Amazon Smile account, and took in donated supplies. Those supplies were then collected, put onto pallets, and flown to Puerto Rico, along with one staff member, by a fruit-shipping business in Miami that was owned by a member’s husband. That staff member oversaw distribution of the 80 or so pallets of donated supplies via all-terrain vehicles, off-road motorcycles, and on the backs of farm animals.

Kaplan’s major complaint regarding Puerto Rico was that his organization did not have any direct contacts with the government, which limited the organization’s potential impact. “There was a need for pediatric critical care nurses, and we have plenty of those, but we could not get a clear answer for how many were needed, where they should go, how long they would be deployed, what clearances they needed, and whether or not their license was appropriate because they came from many different states,” he explained.

Shifting gears, Kaplan talked about the possibility of embedding a health care provider into a civilian tactical team as one way to build change from the ground level up. “We have heard about teaching law enforcement, but we have not heard about partnering with them in a robust way,” he said. In his case, it took, as he put it, two cups of coffee, two donuts, and one croissant for his town’s leadership to buy into this idea, but then it took 3 years for his university to okay the idea. The university, he explained, was concerned about workers’ compensation, how his time would be valued, who would fill in for him when he was deployed with the team, how his participation translated into relatable relative value units, and whether his service with the team would count toward reappointment or promotion. Ultimately, the university decided this activity would qualify as an outreach activity of its trauma system. In Kaplan’s mind, serving with the local tactical team was a way of demonstrating that the health care system was an actual partner that could help the team do its job better.

One benefit of this partnership was that he and others who participated in the program received training on how to use tourniquets and pack

wounds that could be used on a daily basis when law enforcement deployed for non-routine but regular occurrences. Expanding this type of collaboration would be one way to guide change at the local level, said Kaplan, because it responds to a perceived community need while also increasing capacity for responding to disasters.

Kivela, speaking from his experience as an emergency physician in Napa, which has experienced two major fires, an earthquake, and mass shootings over the past several years, echoed Engle’s comment that having to evacuate a hospital is a game-changing event. “No one is really ever prepared for that,” he said. One lesson he and his colleagues learned during the evacuation of several hospitals during the recent wildfire catastrophe was that including a physician or a nurse on non-traditional transportation, such as a bus, facilitated the evacuation process. Kivela noted that while gaining experience is inevitable when responding to a disaster, he is not sure that learning is. To facilitate learning, he suggested that the federal government should create a home for emergency systems of care that would serve as a repository of lessons learned.

One big challenge he and his colleagues faced during the wildfires was that cell phone towers in the area burned down, making it impossible to communicate with his providers. In addition, hundreds of doctors and nurses lost their homes during the fires and have been unable to find housing. Many are therefore leaving the area, leaving it vulnerable to a subsequent disaster.

Myers, speaking as a member of the National Association of EMS Physicians, noted that he and the 650 board-certified members of the association look at the world from the community perspective in toward the hospital. Noting that multiple discussions over the course of the workshop talked about the need to create a public–private partnership with ASPR, he committed his organization and others to establishing a roundtable that would allow that type of partnership to be clearly channeled through physician specialty organizations. He also said his organization wants to work with the Joint Commission, which looks from the hospital outward, to change the mechanism by which drills are conducted and scored to include a region rather than just a single hospital. “We think that would be a wonderful mechanism to improve response across the community and enhance that public–private partnership,” said Myers.

When it comes to crossing state lines, the EMS community developed the Recognition of EMS Personnel Licensure Interstate CompAct (REPLICA) program. REPLICA provides qualified EMS professionals licensed in their home state to a legal privilege to practice in another state. So far, 12 states have signed REPLICA into law, and Myers said he would welcome the federal government to encourage every state to adopt the compact. He also noted that EMS engages in public–private partnerships

routinely, and he cited the public–private partnership to provide 911 responses in the District of Columbia as one of the best in the nation. Such partnerships, he said, can be amplified during disasters.

As a final note, he said it was important to consider the mental health of first responders during a disaster. Holders of an emergency medical technician credential, he said, are 1.4 times more likely to commit suicide than other members of the general public. “For our responders to be ready to enter into disaster, we have to support them in the regular time as well and then particularly after times of disaster,” said Myers.

The final panelist, Paul Hinchey, pointed out that AMR, which has a contract with FEMA to provide resources in the event of a disaster declaration, is a notable example of a public–private partnership. Recently, he said, AMR merged with Air Medical Group holdings to become what might be the world’s largest transportation agency, with multiple communication centers, including a redundant center it operates for FEMA during disasters. In addition to the resources it brings to a disaster, AMR becomes the structure framework that addresses silos and interoperability issues by facilitating the engagement and collection of local resources in advance of an event.

AMR, said Hinchey, believes strongly that local people should take care of local disasters, but it maintains a list of agencies from around the country that are willing to engage with and contribute resources in the event of a large-scale disaster that overwhelms local capacity. AMR has the ability, then, to reach out to those agencies and activate them under a coordinated structure that can deploy both during and after the acute response. In that instance, AMR becomes the link with FEMA that allows some degree of interoperability, he explained. He added that when the federal ambulance contract is activated, AMR serves as the facilitator to bring its resources and other EMS agencies to the response. AMR also tracks the movement of personnel and pharmaceuticals, including narcotics, across state lines in regional disasters in a manner that follows the intent of the laws governing those issues, said Hinchey.

DISCUSSION

Kaplan, referring to Engle’s comment about wanting more regional involvement in conducting hazards vulnerability assessments, said that doing so in the context of a community partnership is essential because it then will include the perspective of everyone else who affects what happens at a given hospital. Involving the community would provide insights into how a nursing home, community center, first responders, and EMS view a hospital’s preparedness, said Kaplan. Incorporating those insights into a hazards vulnerability assessment would improve preparedness because it would then reflect the interconnectivity of the institutions in a community,

including those of state and federal partners. “If you do not embrace what they are bringing, you cannot prepare to interdigitate and interface with what they bring to you when you need it,” said Kaplan.

Krohmer asked the panelists how they incorporate other local health resources into their plans for a coordinated response. Kivela, from his perspective on the EMS side, said he and his colleagues have established a community paramedicine program that looks at patients after they are discharged from the hospital. One thing he learned during the recent fires from patients who were evacuated from several hospitals is that many of just wanted to go home. He suggested that it might be worthwhile to think about using EMS to check on patients to make sure they are okay. He also noted that when moving vulnerable individuals out of evacuation centers, many were fearful they would lose the possessions they had with them, which points to the importance of meeting people at their preferred location during these types of events.

Myers commented that CMS will provide to any community the number of patients by zip code who are CMS beneficiaries and who have home medical devices that require power, oxygen, or other supplies. Having this information can help the regional public–private partnership to plan to have the required supplies and power sources or have transportation prearranged to meet the needs of those individuals. He also noted that during an event, EMS is likely to be the only source of care for individuals who are on a home health care plan, and regional plans need to account for that and not assume that those individuals will be able to receive care from their usual providers.

Kivela pointed out that freestanding emergency departments may be called on to provide surge capacity or pick up the slack if a hospital closes, but they are not eligible for reimbursement from CMS for Medicare or Medicaid beneficiaries. Engle confirmed that and noted that emergency departments attached to the CMS license of a hospital are able to accept Medicare, Medicaid, and Tricare patients. In Houston, he added, freestanding emergency departments are not required to participate in SETRAC and can decide whether or not to participate. SETRAC has a freestanding emergency department task force that is trying to determine what type of patients can best be served in those facilities so that EMS will be able to better determine where to take patients with specific needs during a disaster. During Hurricane Harvey, he added, those facilities were often the only choice for EMS to use.

Hinchey said it is difficult to use a facility that has never been used before and that has not participated in planning and drills. He recounted that when he was the medical director for Austin, Texas, the city engaged freestanding departments that were part of a provider network in all of the planning activities because they were deemed to be important receiving

facilities. Those activities included helping the freestanding emergency departments be better prepared to receive and treat patients during a disaster who would normally fall outside of their usual scope of care. “If you are going to include them, the discussion needs to be held up front and they need to be part of the normal response,” said Hinchey. “If they are not part of your normal response, it is always a challenge to throw something new on the table when everything else is coming unglued.” Kaplan commented that the computing power of the U.S. National Laboratories should be harnessed to simulate what would happen if these facilities are or are not included in a response.

Kivela recalled there was a lack of communication among the hospitals, EMS, and the community during the fires in northern California. “People kept calling the hospitals,” he said. “They did not know what to do or where to go.” His suggestion was for health care providers to think about how they can use social media during a disaster to keep the community up to date on the situation and where resources are available for community members who need help. “The last thing you want is somebody going out in the flood trying to get somewhere and that place does not exist,” he said.

Bruce Evans from the Upper Pine River Fire Protection District said that as a fire chief, his equipment is listed in a number of databases, include AMR’s national ambulance strike team, the national interagency resource ordering and status system, a Web Emergency Operations Center (WebEOC) through the State of Colorado. During the Napa fires, FEMA made one call to AMR, which AMR made an immediate request for resources from his strike team, and a rig was on the road, headed to Napa within 12 hours. By contrast, when California declared a Stafford Act emergency for the Napa situation, that triggered an emergency management assistance compact request for 30 fire engines from Colorado. “That resource order came, and we finally had a truck that was able to get on the road 5 days later, by which time the damage was done in Napa,” said Evans. In his experience from several incidents, the public–private partnership between FEMA and AMR is much more efficient than the government-to-government system. In his opinion, the fault lies with bureaucracy that gets in the way when two states are deciding who is going to pay for what, who has the approval authority, how many signatures are required, and who signs on the dotted line before somebody actually calls and says get moving.

Hinchey remarked that one problem with the FEMA–AMR system is that it conflicts with the disaster medical assistance team (DMAT) program that coordinates fire-based EMS. He said that many fire agencies, which have resources they want to contribute, are reluctant to sign onto the AMR system because they are worried about potential conflicts given that the two systems are not coordinated yet. Evans said that while he relies on

DMAT funds to supplement his usual funding sources, the AMR program reimburses him within 30 days, whereas the DMAT program takes months.

Kirsch asked the panelists what they see from the ground level as the ideal way to coordinate preparedness and response activities for health care systems. Engle replied that from his perspective, the regional advisory councils are an excellent mechanism for ensuring that hospitals and other institutions are getting the necessary resources. Myers agreed and added that the regional advisory committees are the most accepting group and by their very existence are an effective public–private partnership. Kaplan noted that regional advisory committees are effective, if a region has one. In the absence of one, a regional trauma center or regional coalition can serve as a coordinating body. Kivela added that regional coalitions are important for when a disaster encompasses many jurisdictions.

Melissa Harvey asked the panelists for their thoughts on what the optimal composition of a regional coalition would be and if it is possible for a coalition to be too big to be manageable. In Houston, said Engle, the coalition is still in its infancy and trying to figure out what kind of incentives it needs to get organizations to participate. “Without that or without some type of negative reinforcement, you may not get the participation because there [are] a lot of competing resources for health care dollars,” he said. Kaplan remarked that a coalition needs a meaningful membership roster and a means of seeing itself as part of a larger framework.

Harvey then asked if a requirement for a coalition to fund a full-time position would help with right-sizing the coalitions. Engle said that might be helpful and having a full-time employee could lead to better allocation of resources at the local level. His hope, though, is that those joining coalitions would be doing so out of their desire to protect the public. Kaplan suggested that instead of funding a full-time employee, it might be required for each coalition to have at least two facilities that are in different tiers with regard to patient care.

Michael Consuelos noted that the different iterations of the Hospital Preparedness Program have driven degradations of capabilities in some areas and upgrades in others. As an example of the former, he said a hospital in suburban Philadelphia got funding during HPP’s early years and was able to establish a decontamination unit capable of operating 24 hours per day in the event of a large-scale chemical or biological event. Today, however, that hospital reports that on a good day they can run the unit for 8 hours because both equipment and training have degraded over the year. His concern going forward is that as the coalitions get larger, funding and resources will be spread thinner and thinner. “I think it is important to understand at some point there are some critical pieces that we have to make sure are continuously funded and operational, otherwise, no matter how many people we have around the table, the critical infrastructure is

not going to be there,” said Consuelos. Another concern he has is making sure that the workforce is being trained adequately at the coalition level as the number of institutions and people participating grows.

William Wachter from North Central Baptist Hospital remarked that the most important part of belonging to a coalition is coming together to do something every day, whether that is holding classes and drills together, gathering data collectively, or participating in other activities. Tener Veenema added that the nation’s 3.1 million registered nurses, as well as advanced-practice nurses, nurse midwives, nurse anesthetists, and nurse mental health professionals, will play a huge role in any response and therefore, nurses should be at the coalition table. She also noted that of the 3.1 million registered nurses, only 37,000 of them define themselves as public health nurses. “We have a potential shortage here for events where we need nurses outside of the hospital acute care health system,” she said. Veenema also noted that most Federally Qualified Health Centers and stand-alone urgent care centers are understaffed, something that needs to be considered when thinking about these as potential resources for surge capacity.