2

Privacy, Security, and Confidentiality of Data Sharing and Storage

The second day of the workshop was devoted to discussions about how to protect the privacy, security, and confidentiality of data produced in international research collaborations. The day was divided into four sessions; each focused on a different aspect of this subject and featured perspectives from speakers that approached the policy challenges of protecting data privacy and security from varying roles in government, universities, and industry. The first panel discussed some of the general theoretical issues to consider when developing international research agreements to establish a common level of understanding among participants about the landscape of concerns and principles within agreements that pertain to privacy, security, and confidentiality of data sharing and storage. The second panel considered domain-specific challenges to collaboration and addressed issues discussed in the preceding session to enable a “compare and contrast” across issue-specific domains. The four presentations in this session also served to seed the breakout group discussions that occurred later in the workshop. The third session featured a presentation on responsible data sharing in the context of international and interdisciplinary research, and the fourth session considered purpose-specific, population-specific, and data type-specific concerns regarding privacy, security, equity, confidentiality, and resilience with consideration for regional sensitivities.

THE UPSIDE AND DOWNSIDE: PROTECTIONS, INCENTIVES, DISINCENTIVES, AND RISKS

The first panel session featured presentations on legal and technical issues by Ruxandra Draghia, Vice President of Public Health and Scientific Affairs at Merck Global Vaccines, and Nick Feamster, professor of computer science at Princeton University’s Center for Information Technology Policy. An open question-and-answer session was moderated by Mark Seiden, Director of Information Security at 1010data and Security Advisor at Internet Archive. Then, Kristin Tolle, Director of the Data Science Initiative at Microsoft Research Outreach, Brad Fenwick, Senior Vice President of Global Strategic Alliances at Elsevier,

and Stuart Haber, chief scientist at Auditchain, gave talks on political and economic concerns, followed by an open question-and-answer session moderated by Mark Seiden.

Legal and Technical Concerns

The process to develop the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which went into effect on May 25, 2018, took place over several years of intense negotiations. GDPR, explained Ruxandra Draghia, applies to the processing of personal data, either wholly or partly by automated means, but it does not apply to the processing of data in five specific instances:

- when it is in the course of an activity that falls outside the scope of European Union law;

- when it is by member states carrying out activities that fall within the scope of common foreign and security policy;

- when it is by a natural person in the course of a purely personal or household activity;

- when it is by competent authorities for the purposes of the prevention, investigation, detection, or prosecution of criminal offenses or the execution of criminal penalties, including the safeguarding against and the prevention of threats to public security; and

- if the person is deceased, in general.

One of the essential elements of GDPR, said Draghia, is its territorial scope in that it now applies to all companies processing personal data of subjects residing in the European Union, regardless of the company’s location. GDPR applies to data clouds, she added, and so do the penalties, which can reach €20 million or 4 percent of annual revenue, whichever is higher, per infraction. She also used a hypothetical situation to explain two terms, controller and processor, which are germane for determining who is responsible for following GDPR regulations. If company X sells a medical device to consumers and uses company Y to email consumers on its behalf and track use of the device, then company Y is called the data processor company and X is the data controller with regard to that email activity and has principal responsibility. One effect of this distinction is that if a consumer wants to revoke the consent they may have given, they must contact the controller to initiate that request, and the controller must go to the processor, who must act in good faith to remove those data from its database.

GDPR, said Draghia, was developed to serve as a harmonized and simplified framework for data protection to replace the patchwork of rules, regulations, and laws that had proliferated in the European Union. It includes one interlocutor and one interpretation, creates a level playing field across the entire European Union, and cuts red tape by abolishing most prior notification and authorization requirements, including those regarding international transfers of data.

The legal basis for processing health data is governed by two articles in the law, one of which says that there needs to be clear, explicit, affirmative consent, so simply clicking a box is no longer allowed, she said. A 15-page consent full of legalese that few if any participants in a clinical trial will read or understand will not pass muster as clear, explicit, and affirmative consent, and nor will the elaborate terms of conditions used by companies, which Draghia predicted will therefore be trimmed down substantially. At the same time, consent for research can be for relatively broad content for specific areas of research, such as consent to use a patient’s tissue sample for all types of brain cancer, not just glioblastoma multiforme.

GDPR does contain a provision that further conditions, including limitations, might be included by member states regarding the processing of genetic, biometric, or health data, though the European Commission has created working groups to harmonize national laws. It also includes exemptions from obtaining clear consent to process genetic, biometric, and health data. One exemption, which rare-disease advocacy groups lobbied for, is when the individual makes the data public, such as by posting it on Facebook or Twitter as part of an effort to share information about a rare disease. Another exemption applies to situations where data release is necessary for reasons of substantial public interest, such as when trying to stop cross-border transmission of an infectious disease such as Ebola or ensuring high standards of quality and safety of health care and of medical products or medical devices.

Data processing is also exempt from the consent process when it is necessary for the purposes of preventive or occupational medicine, for assessing the working capacity of an employee, or for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes, or statistical purposes. This latter provision means that if data collected today, for example, suddenly become useful in the future when combined with new data, the participants in the original study do not need to be re-consented. Anonymized data, Draghia added, fall outside of the scope of GDPR.

In addition to requiring consent and terms of conditions to be transparent, clear, and written in accessible language, GDPR also confers other rights for individuals, including the right to have their own data and the right to object to the use of their data in any specific type of processing. Individuals now have a right to be informed about and object to one company transferring data to another company and to not be subjected to automated decision making. Regarding the latter, Draghia explained that if a company decides to move its data from Europe to China, individuals have a right to say no. On the other hand, when individuals move from one country to another, they have the right to take their electronic health record with them. Finally, consumers now have the right be notified of a data breach within 72 hours of it occurring. Draghia noted that member states have the right to maintain or introduce further conditions and limitations, but the general idea behind GDPR was to minimize those instances and instead strive for harmonization.

When GDPR was being developed, said Draghia, it was decided to refer to the existing European infrastructures for storing, curating, and processing data

that had been developed as part of Europe’s Horizon 2020 Societal Challenge to address health, demographic change, and well-being. Such infrastructures included the Information Platform for Chemical Monitoring and the Biobanking and Biomolecular Research Resource Infrastructure. These existing architectures provide for data management plans for projects, including those with multiple project partners and in multinational settings. In particularly the Biobanking and Biomolecular Research Resource Infrastructure includes a code of conduct that underpins the ethical and compliant conditions that apply to the use of biomedical data. She noted that existing European and international research networks have worked with the European Union to facilitate the coordinated actions needed to comply with GDPR.

Draghia noted that a court case involving Facebook data and safe harbor provisions led to the ruling that safe harbor provisions do not protect the data of individuals. In fact, she said, the protections of personal data in the United States are in general not compliant with European rules, which led to the concern that U.S. and European researchers would not be able to work together. Passage of GDPR and its impending application in May 2018 led to a flurry of work by U.S. companies to develop binding corporate rules for protecting individuals’ data that would be compliant with GDPR. To replace safe harbor provisions, some companies are using Privacy Shield,1 two self-certification frameworks designed by the U.S. Department of Commerce and the European Commission and Swiss Administration to provide companies on both sides of the Atlantic with a mechanism to comply with data protection requirements when transferring personal data from the European Union and Switzerland to the United States. Draghia said she believes the rules of engagement are much clearer with the provisions included in GDPR, and she believes it will foster high-quality research internationally.

Next, Nick Feamster discussed the different actors that are gathering data about individuals and the diverse ways they are doing so. He started by explaining online behavioral targeting, in which publishers of content on the internet are connected to ad networks that, in turn, use the information they collect on the sites and individual visits to place targeted ads on the content publisher’s Web pages. “What is effectively going on with behavioral targeting is that advertisers, by virtue of their interaction with these ad networks, can place ads in ways that are very, very specific to your interest, your likes, what you have done in the past, your demographic profile, so on and so forth,” said Feamster. “The more targeted the ads can be toward your behavior and profile, the higher value the placement of those ads are.” As a result, there is huge incentive in this ecosystem to collect as many data as possible about an individual.

As far as who is collecting these data, the answer, said Feamster, is everyone. Much of the data are collected on the internet, but mobile devices, internet service providers, virtual private networks, and the Internet of Things also are rich sources of data on the behavior of individuals. On any given website, there are tens to hundreds of trackers linked to ad networks, he explained, and they are

___________________

1https://www.privacyshield.gov/welcome (accessed May 28, 2018).

informed by cookies that track the websites that users visit. For example, when someone visits YouTube to watch a video, YouTube places a cookie on the user’s computer. When that user visits another website containing a YouTube video—the BBC or The New York Times websites, for instance—the cookie records that information and Google, YouTube’s owner and one of the largest ad networks, starts building a profile of that user. The more videos it can place on the sites of different content publishers, the easier it is for Google to track individuals as they go around the Web. Feamster explained that every site with a Twitter share button or Facebook like button is collecting information on individuals that visit those sites, without the user’s explicit consent. In fact, on a typical top-50 website, there are an average of 64 trackers, each placing and receiving cookies from the individuals who visit those sites.

Cookies are not the only way information is gathered about users. Even when using cookie blockers and ad blockers, the unique characteristic of an individual’s browser can enable tracking of individuals. Feamster explained that of the hundreds of thousands of different browser configurations, there are perhaps a few hundred people with the identical configuration. In addition, trackers can trade information from cookies and browser configurations with other cookies using a technique called cookie synchronization. He noted there are other, more pernicious aspects of tracking as well.

Mobile phones are another important source of information gathering for advertisers, one that collects information on every Wi-Fi network the phone connects with as it passes through an area, as well as when the phone’s owner tilts it—that is important because it indicates the user is looking at the phone—and barometric pressure, which can provide information on what floor the user is on inside a shopping mall, for example. Together, said Feamster, that information can tell the phone’s operating system exactly what store a user is passing by at any given moment. Similarly, internet service providers and some virtual private networks are also collecting information in a drive to become players in the advertising space.

The next privacy frontier is the Internet of Things (IoT), the collection of devices making their way into the smart home of the future. “This is probably the Wild West as far as [privacy experts] are concerned,” said Feamster. “If you thought browsers and phones were bad, I think it is going to get worse.” He explained that while large companies providing smart devices are generally good at software updates and encryption, others are not. A Wi-Fi-enabled photo frame that he and his collaborators examined, for example, was sending unencrypted information over the internet, as was a Wi-Fi-enabled video camera. “Not all IoT devices are bad, but buyer beware,” said Feamster.

This potential for abuse has caught the attention of policy makers and regulators, he said. In one case in 2017, for example, the Federal Trade Commission and New Jersey attorney general levied large fines on a smart television manufacturer for collecting information about what viewers were watching without their consent. His advice to those at the workshop with children was to avoid buying them internet-connected toys. Looking to the future, Feamster said he is not quite

sure what the mechanisms will be to address privacy issues in an increasingly interconnected world. While installing an ad blocker might break a website, there are workarounds, but what happens when an IoT ad blocker shuts down a furnace and the pipes freeze, he asked. From a technical and policy perspective, there are many challenges with respect to privacy. “There are certainly questions here about consumer protection, when do we bring in the regulators, and how do we bring them in,” he said. “To what extent do we rely on industry to self-regulate and what can we assume about consumers and their behaviors?”

Ending on a positive note, Feamster said he believes privacy is a solvable problem, but not one that will be purely technical. One step forward would be for every smart device to provide easy-to-check information about what it was collecting about users, something that is difficult today. He noted that every website has a privacy policy, but adding in trackers from dozens of various places makes privacy so complicated that there is no hope of a consumer understanding it, he said. Getting consent, he added, is a hard problem that is getting harder. At the same time, most people like that websites seem to know what ads to display for them. “How do we balance the benefits of behavioral advertising and tracking with the massive collection of data that is going on?” asked Feamster. “Thankfully, security practices continue to improve, but we have a lot of work to do on the rest of these topics.”

Responding to a question about how all of this affects those who use the Web to communicate research information or to collection information for research purposes, Feamster said that the Federal Communications Commission, in its most recent rules on privacy, included a researcher exception. He also noted that he hears regulators and policy makers talk about aggregation of data as the way to protect privacy, but some applications, such as the ability to detect a compromised IoT device, depend on examining disaggregated device-specific information, in addition to the examples that Garfinkel noted where aggregating data does not guarantee privacy. He also commented on developments in which artificial intelligence and machine learning methodology could be used to mine data to predict health-related incidents such as a person with bipolar disorder starting to have a manic episode based on data usage or a person displaying suicidal behavior based on online postings on social media. Deciding who gets that information and whether intervening is ethical or not is an open question, he said, but one that needs an answer.

Political and Economic Concerns

Microsoft’s approach to security and privacy is perhaps a little more extreme than at other companies, said Kristin Tolle, so much so that the company’s products are not allowed to share data between one another. She agreed with previous speakers that triangulation, which combines data from two or more data sets to identify individuals, is one of the biggest risks in the privacy realm, and for that reason, Microsoft only shares data from specific products through strict nondisclosure agreements with researchers. Those agreements, she said, are written to

ensure that the person taking the data is legally responsible and liable for taking those data and securing them in a way that does not compromise people’s privacy.

Regarding GDPR, Tolle wondered why it or something like it had not been developed sooner and why it took European regulators to get U.S. companies to finally get serious about this type of privacy issue. In her opinion, it should be part of a company’s business to not only take these provisions seriously, but also help its customers be compliant. “That is something we are embracing wholeheartedly and would like to see more of, not less,” said Tolle.

The thing that Tolle said probably frightens her the most is the potential for artificial intelligence to affect privacy. “We not only need to start thinking about the data itself, but the products of the data and what privacy looks like,” she said. In thinking about how to build privacy into products, her approach would be to start with privacy and then build the product and not treat privacy as an afterthought.

Brad Fenwick pointed out that Elsevier, which is the world’s largest publisher, is transitioning from a content company to a data company, which aligns with its sister firms LexisNexis and Risk. In fact, Elsevier is now the fourth largest data company in the world, with Bloomberg probably being the world’s largest data company today. “The amount of data we ingest and evaluate is quite astonishing,” said Fenwick. “If you are a researcher at a university, a technology company, or a government, you are our client. We are either taking data from you, giving you data, or exchanging data with you.” He noted that Elsevier has a profile of every individual who has ever published in any of its 5,000 journals. Lexis has a profile on every individual who has ever bought a car, had a mortgage, got married, had a complaint filed against them, or been quoted in a newspaper. In addition, Elsevier links to all the images on the Web. “As a big data company, if it is out there, we will ingest it and figure out how to use it later if we do not already know how to use it,” he said. In his opinion, any business that is not using data analytics to inform its business will probably not be in business for long.

Regarding the topic at hand, he noted that research is data driven and is increasingly multinational and collaborative. More importantly, data give research validity, and the expectation that the underlying data supporting a publication should be available is going international. There is an increased expectation from funders, he said, to make data more transparent for reproducibility purposes, just as there is an increased expectation that data should be available so that society can reap the economic gains that come from using data that are often produced using public funds. The challenge, said Fenwick, is that although data cannot be patented or copyrighted, it does provide the underpinning for patents and copyrights, which is changing the behavior of intellectual property offices at universities to control the flow of data out of their institutions.

As a global company, harmonization of how data are generated is a barrier to Elsevier, and the company has certain ethical issues in some countries with institutional review boards, which may not be required in some parts of the world. “If you do not appreciate the ethics of how the data were generated and then you build on top of that, whether for political policy purposes or business operations,

there is a huge risk,” Fenwick explained. He noted that researchers are inherently suspicious of other people’s data, since their reputations depend on working with good data. Increasingly, though, as collaboration increases globally, researchers are being put in the position of having to trust data generated by others and to think more seriously about the source of the data and who owns it. In addition, cross-border sharing of data is a difficult matter for his company.

In his final remarks, Fenwick commented on the link between ownership and storage, curation, and security of data, all of which come with great cost. Elsevier, for example, has begun offering to store the data that underlie the papers published in its journals. However, it did not consider the cost of doing so. This is a serious issue for data aggregators such as Elsevier and Bloomberg, both of which accumulate and organize data and return it to users in an accessible form. How to pay for that is an issue, he said.

To finish the session, Stuart Haber spoke briefly about the cryptographic mechanism known as blockchain that provides a way to preserve data integrity by time-stamping and checking bit-by-bit integrity (Bayer et al., 1993; Haber and Stornetta, 1991, 1997). Preserving data integrity, said Haber, is orthogonal to the issue of encrypting data and deciding who has access to it. As to why blockchain, or any cryptographic technique, is germane to political concerns, he referred to a paper by the cryptographer Phillip Rogaway (2015), who argued that because cryptography rearranges power and configures who can do what from what, cryptography is inherently a political tool, and it confers on the field an intrinsically moral dimension to do a better job protecting data and resisting mass surveillance.

In the discussion that followed, the panelists and several workshop participants talked about the need for open and transparent discussions regarding the development of ethical guidelines for data sharing and ensuring the integrity of data. In particular, it was noted that one challenge going forward is to further develop the nascent work being done to identify methods of protecting against false conclusions being driven by corrupt data. It was also noted that cryptographic techniques such as blockchain do nothing to prevent publication of bad or false data, but only serve to protect the integrity of data once they are published.

DOMAIN-SPECIFIC EXAMPLES

The second panel session of the day provided a diverse set of domain-specific examples of how ethics and data issues play out in international research collaborations. The panelists were Joseph Pelson, professor and Emeritus Director of the Space and Advanced Communications Research Institute at George Washington University; Eric Perakslis, Chief Science Officer at Datavant; Shelley Stall, Director for Data Programs at the American Geophysical Union; James Shultz, founder and Director of the Center for Disaster and Extreme Event Preparedness at the University of Miami School of Medicine; and Nancy Potok, Chief Statistician of the United States. Following the five presentations, Ruxandra Draghia moderated an open question-and-answer session.

Communications and Space Science

The idea of using supersecure cryptographic coding methodologies such as blockchain is becoming increasing critical to maintaining the security of information, goods, and values transmitted electronically, said Joseph Pelton, but there is both good and bad associated with protecting digital information. The good is in the protection such methods afford to digital transactions and protecting an individual’s identity and privacy, but the bad is that these methods can be used to disguise a person’s identity and enable them to be engage in undesired activities such as trolling or committing crimes. “The push for privacy, for borderless and clandestine currency, and for anonymous communications or data protection has produced the growth of the dark Web, where people are trying to do nefarious things,” said Pelton. He also noted that in 2016, the online political reporting network Buzzfeed reported that the top fake new reports online had a significantly larger impact on measures of facetime over actual legitimate factual news stories during the U.S. presidential election. Buzzfeed noted that the engagement of Facebook users with “fake news” as purveyed by bots and trolls exceeded the page views of 19 legitimate news outlets combined (Pelton and Singh, 2018; Silverman, 2016).

There is a need, said Pelton, to protect vital information against cloud cybertheft, power outages, and solar storms, with the last of particular importance. The reason, he explained, is that there are some models suggesting that the protective shielding against solar storms provided by the Earth’s magnetic field will fall as much as 15 percent in the coming decades, which means that electronic systems and the data they produce and maintain will become more exposed to damage from these storms. As the population of cities grows, an increasing number of people on the planet will be vulnerable to the infrastructure damage that could result from such storms.

The growth of artificial intelligence and machine learning has the potential to create an additional data security issue. To explain, Pelton said that digital algorithms using artificial intelligence will be used to preprocess enormous amounts of data before the data get to the researcher. While this may make large data sets more amenable to human analysis and understanding, it raises the possibility that there will be a time when “sentient” processors might distort data for various reasons, as was the case with the computer HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Similarly, in the age of IoT, traffic coming from smart devices is projected to increase by a factor of 30 in the next 20 years, which Pelton said means most communication will be between machines. “We really do need to be paying attention to human-machine interface protections if those algorithms go wrong,” he said.

One instance playing out today involves what to do with the data gathered by Mars remote sensing spacecraft. Sending the data back in raw form would be ideal, but very slow, while preprocessing the data would increase data transfer efficiency by 20-fold. The issue with preprocessing is that it is difficult to ensure the integrity of the data after it has been processed. Kristin Tolle noted, however, that it may be better to test the ability of artificial intelligence to filter and sort data on Mars than here on Earth, a comment with which Pelton agreed. Both

agreed that humans need to be involved in the decisions made by machines to act as a brake when something goes wrong.

Health Care and Biomedicine

Eric Perakslis discussed the developments around data ethics in the health care and biomedicine domain by describing a number of projects he has been involved in throughout his career that have shaped his understanding of the challenges of managing and protecting the data of healthcare patients, especially those in vulnerable positions.

Perakslis described four projects related to developing data management systems and platforms with varying degrees of privacy and security concerns. The first project was tranSMART, an open-source knowledge management and data analytics platform, which uses open-source software to put the company’s preclinical and clinical trials data into the cloud and integrate those data across therapeutic regimes and stages of drug development. (Scheufele et al., 2014). Today, this platform is administered by the tranSMART Foundation and is in use at no charge by 300 to 400 different governments, agencies, and nongovernmental organizations around the world.

The Undiagnosed Diseases Network for the National Institutes of Health (Gahl et al., 2015, 2016), is a database of information on children who appear to have one-of-a-kind, often fatal diseases. The unusual thing about this network is that patients are not de-identified simply because they cannot be. “You are deeply phenotyping them and sequencing their entire living pedigree,” said Perakslis. While the data are protected by the provisions of the Federal Information Security Management Act and are kept behind a firewall, the patients and their families allow the information to be made public with the hopes of finding others with the same phenotype to allow for further research.

Perakslis also mentioned the development of a system for handling the enormous amount of data generated in Takeda Pharmaceuticals’ digital clinical trials employing wearable sensor devices (Izmailova et al., 2017). This is a relatively new development in the pharmaceutical industry but one he believes will become far more important in the near future. “There is a lot to be learned about this space, but we are getting there,” he said. One issue that needs addressing is the inferior quality of the sensors available today.

The last project Perakslis mentioned was an app called CommCare which was developed out of a need during the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone to improve diagnosis. The app walked people through their symptoms to help them differentiate between a possible Ebola infection and the more common symptoms of malaria. While there were many doubters that the people of Sierra Leone would ever figure out how to use this app, the fact was that smart phones are ubiquitous in West Africa, and the people absorb these types of technologies quickly. He noted that a year and a half later, he received a text message from one of the residents who was involved in this project telling him that there were now

110 community health workers using the CommCare app as part of an expanded mobile medical surveillance and data collection process.

There are many complexities in conducting good clinical practices and research in areas like the hot zone in Sierra Leone and other countries, Perakslis concluded. He emphasized the importance of investing in capacity building, respecting the wisdom of the locals, and listening to the local Ministry of Health.

Earth, Space, and Environmental Sciences

The American Geophysical Union (AGU), explained Shelley Stall, has data management responsibilities related to its publications and to its members and their scientific work. To help with that responsibility, the AGU has issued a position statement stating that Earth and space science data are a world heritage that when properly documented, credited, and preserved will help future scientists understand the Earth, planetary, and heliophysics systems.2 More recently, in September 2017, AGU’s Board of Directors adopted an updated ethics policy defining harassment as scientific misconduct on equal footing with fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism in a work environment (Gundersen, 2017; Hanson, 2017). AGU has also been involved in creating the Coalition on Publishing Data in the Earth and Space Sciences, which issued a statement on behalf of every Earth and space science publisher and data repository committing them to making data transparent, open, and protected.

A survey conducted by the Belmont Forum, which works with environmental data, found that researchers have a variety of challenges in using data, with the top four issues being data complexity, finding relevant existing data, a lack of data standards and exchange standards, and data management and storage. “What does that matter for publication?” asked Stall. “If you cannot find data to build your research upon that is valuable to you, and it is not something that you understand, and it is not in a standard that you can use, then you are losing out on using something that already exists.” In other words, she said, if data that support a paper are not discoverable because they are stuck in a supplement or another paper, then they are not benefiting researchers and society as much as they could. To address this problem, a diverse set of stakeholders representing academia, industry, funding agencies, and scholarly publishers came together to design and jointly endorse a concise and measurable set of principles they called the FAIR Data Principles, where FAIR stands for findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (Wilkinson et al., 2016). Stall noted that the bulk of the Earth and space science data is open and findable using Google or any other search engine.

With a grant from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation awarded to the Earth and space science community, Stall and her colleagues are working to align publishers and repositories in following best practices to enable FAIR and open data and to create workflows so that researchers will have a simplified, common

___________________

2 Available at https://sciencepolicy.agu.org/files/2013/07/AGU-Data-Position-StatementFinal-2015.pdf (accessed May 29, 2018).

experience when submitting their paper to any leading Earth and space science journal. The objectives of this project, she said, are to create FAIR-compliant data repositories that will add value to research data, provide metadata and landing pages for discoverability, and support researchers with documentation guidance, citation support, and data curation. In addition. FAIR-compliant Earth and space science publishers will align their policies to establish a similar experience for all researchers. Data will be available through citations that resolve to repository landing pages and will not be placed in supplements.

She noted that these are “deep and very heavy lifts” from both the publishing and repository communities, but both are motivated. According to data from PLoS One, only 20 percent of the papers published in that journal are in a repository, so there will be some substantial changes coming. To drive this effort, stakeholders are working on an 18-month timeline that ends in July 2018 to develop, adopt, and implement guidelines, recommendations, and policies. Stall explained that although AGU is acting as a convener for this work, the solutions have been community driven and build on previous work done by the Coalition for Publishing Data in the Earth and Space Sciences. She also pointed out that the data associated with all publications will be open by default.

Stall then told a cautionary tale about the importance of protecting data. In the December 1, 2016, issue of Science, the editor, Jeremy Berg, published an editorial expression of concern, noting that the authors of a paper notified the journal that the laptop on which all of the data supporting the paper had been stolen (Berg, 2016). Worse yet, the data had not been backed up or deposited in an appropriate repository. The following May, the authors retracted the paper because an ethical review board determined that the data were no longer available, there was no way to build upon the science, nor was there a way to validate that the science was good (Berg, 2017).

Data and Disasters

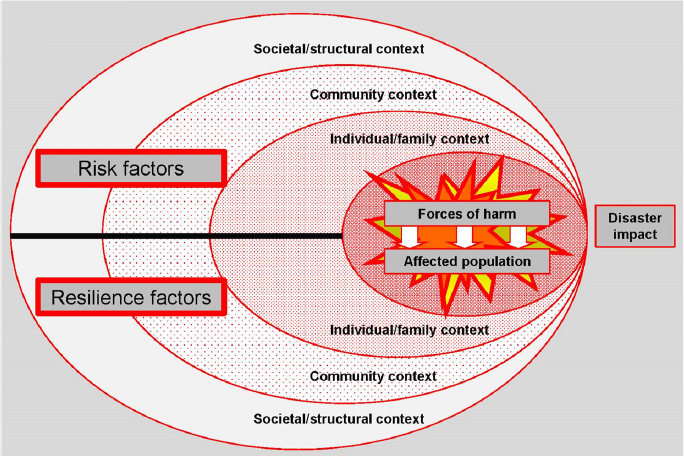

A disaster, said James Shultz, is characterized as an encounter between forces of harm and a human population in harm’s way as influenced by the ecological context. This encounter creates demands that exceed the coping capacity of the affected community and requires the community to ask for outside assistance. In the disaster ecology model that Shultz and his collaborators have developed, the ecological context comprises the individual and family context, the community context, and the societal and structural context, some of which exacerbate risk and some of which build toward resilience (Figure 2-1). He noted that the Center for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters characterizes one subset of disasters as natural, which includes meteorological, hydrological, climatological, geophysical, biological, and extraterrestrial incidents, and another subset as anthropogenic, which includes both intentional and nonintentional. Most nonintentional disasters result from a technological failure, such as a building collapse or a hazardous material spill.

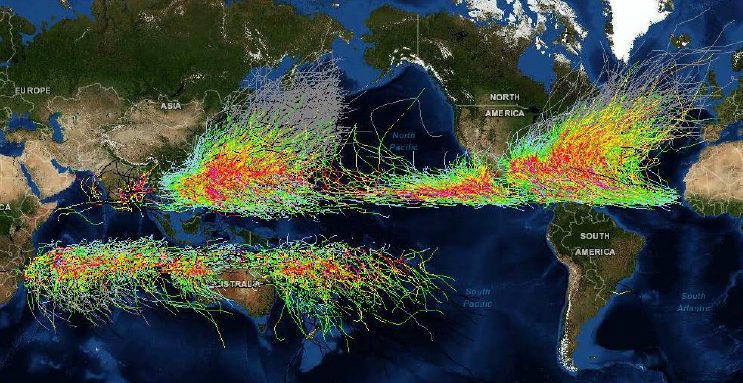

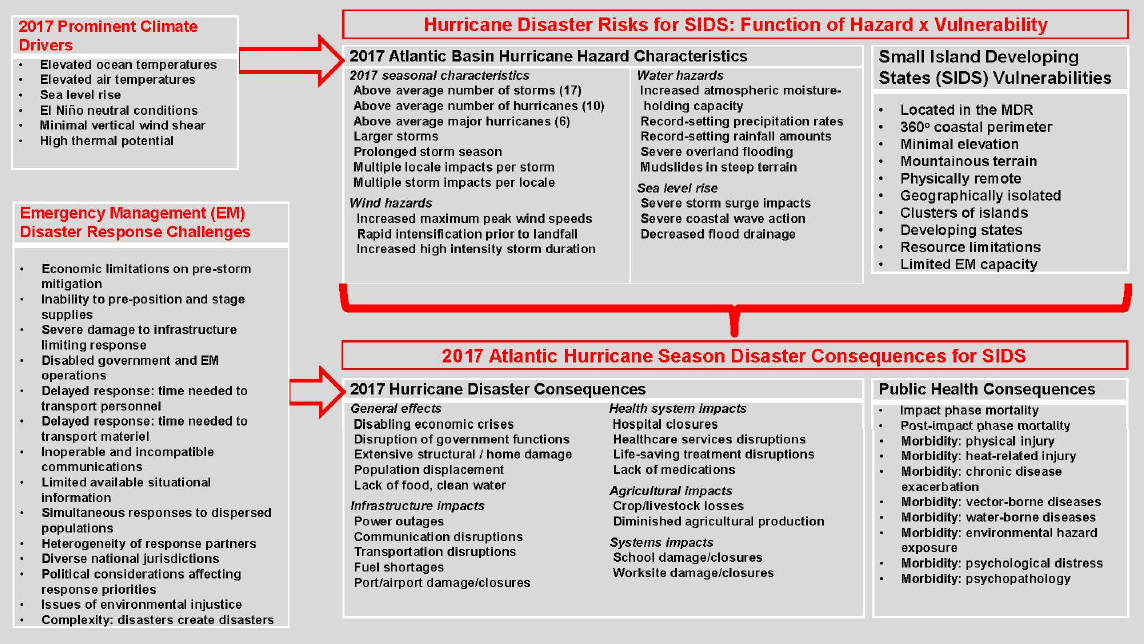

As an example of how data and disasters go together, Shultz focused on hurricanes, starting with the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season. One of the prominent features of the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season was the role that climate drivers played in setting up the hazard characteristics of those storms. “When we look at the climate drivers, we know we have elevated air and ocean temperatures and we have sea level rise,” said Shultz. “In this particular season, we had El Niño neutral conditions that allowed for minimal vertical wind shear that tears hurricanes apart, allowing them to stay intact and very strong.” In addition, the ocean waters were very warm at extraordinary depths, creating a high thermal potential that could provide energy to developing hurricanes. The result of these climate drivers was an above-average number of major hurricanes and a prolonged storm season. He noted that in 2014-2016, there was a record-setting El Niño that suppressed hurricane formation in the Atlantic Ocean but led to an extraordinary number of typhoons in the Pacific Ocean.

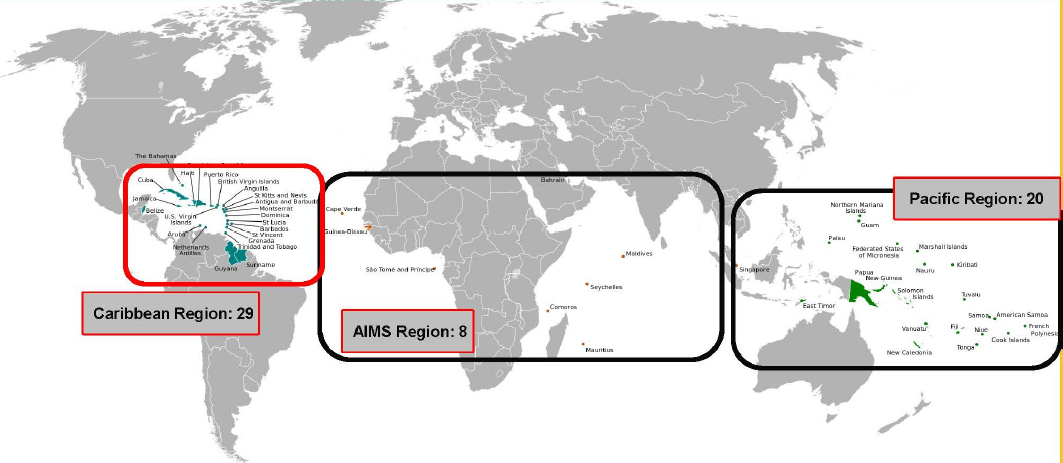

In terms of vulnerability, the small island developing states—some 50 nations and territories so designated by the United Nations—sit for the most part in hurricane and typhoon belts (Figures 2-2 and 2-3). Some of these nations have minimal elevation above sea level and are at risk of devastating floods, while others are mountainous and susceptible to mudslides. As developing states, they tend to have limited resources and limited emergency management capacity, Schulz said.

Data are important for understanding the risks to these nations and for trying to develop ways of mitigating these risks and associated public health consequences (Figure 2-4) (Shultz and Galea, 2017a, b; Shultz et al., 2018). One thing the data reveal is that the psychological “footprint” of these disasters is far bigger than the size of the medical footprint, said Shultz. In a disaster, he explained, the psychosocial consequences extend along a spectrum of severity, where the severity relates to the degree and intensity of exposure. The psychosocial consequences of a disaster also expand across a range of durations. Almost everyone who has a life-threatening exposure to a disaster experiences fear and distress, while a smaller subset will engage in harmful behaviors, such as trying to drive on flooded roadways. A smaller but not insubstantial group, perhaps up to 30 percent of the population, will develop diagnosable posttraumatic stress disorder, major depression, generalized anxiety, somatic disorders, and increased alcohol use.

His final point was that in a disaster the exposure time may be relatively short, but the consequences will last far longer. From a meteorological perspective, Puerto Rico’s exposure to Hurricane Maria in 2017 lasted only 3 days, but 6 months later, there are still resource shortages, human losses, and enduring life changes, including displacement. Understanding all these consequences, from the physical devastation to the psychological and social toll, requires putting together many different data elements compiled by multiple disciplines, said Shultz.

U.S. Government Statistical Data

As the Chief Statistician of the United States, Nancy Potok’s job is to ensure the objectivity, integrity, relevance, timeliness, and confidentiality of federal statistical data across the decentralized federal statistical system. From an international perspective, she leads the U.S. delegation to the United Nations Statistical Commission, which has been engaged over the past few years in putting together the metrics for assessing progress on the 2030 sustainable development goals the United Nations has adopted. “What we see internationally is a varied picture in terms of capacity of national statistical offices and the willingness of governments to create an independent framework for statistical offices,” said Potok. Her worry is that some governments will merely purchase publicly available open data and bypass the national statistical offices and ignore the ethical frameworks for data independence and informed consent. She noted that the United Nations, with the involvement of the United States, has been putting resources into helping nations develop their national statistical offices and establish principles around open data. There has also been a great deal of work, she said, to develop platforms and standards for interoperability, metadata, and data security.

In the United States, protections in the federal statistical system first arose in the late 1880s because the business community was fearful of providing the government with proprietary data and having it shared and released. Then, in response to President Nixon firing people at the Bureau of Labor Statistics because he did not like the unemployment data the agency was releasing, Congress passed legislation that put today’s protections in place and made the U.S. statistical system much more independent of political influence, said Potok. Part of her job today is to develop and release standards that reinforce that independence, which she added is tested to some degree by every new administration.

In her position, she considers data to fall into one of three tiers: open data, restricted data, and highly restricted data that are collected under a pledge of confidentiality. For open data, the only significant issue from a statistical perspective involves re-identification, which has become a very real concern. She and her colleagues are taking a hard look at what they can release as public data given the re-identification risk and the pledge of confidentiality given when collecting those data. Some of those data, she said, may be moved into the tier of more restricted data.

As an example, she noted that the National Center for Health Statistics is using what is called the Five Safes framework, which breaks down the decisions surrounding data access and use into five related but separate dimensions: safe projects, safe people, safe data, safe settings, and safe outputs.3 The safe projects domain asks whether the specific use of the data is appropriate, lawful, ethical, and sensible. The safe people domain examines whether the researchers can be trusted to use the data in an appropriate manner. The safe data domain questions if the data contain sufficient information to allow confidentiality to be breached.

___________________

3 Available at http://www.fivesafes.org/ (accessed May 29, 2018).

The safe settings domain looks at whether the access facility limits unauthorized use or mistakes, and the safe outputs domain examines the risks of re-identification and disclosure related to the way the users are going to release their findings. “That is a framework that we are looking at more because researchers do want access to restricted data, and if we have to keep pulling back on what is going to be available publicly, then restricted data have to become more readily available in locations that can be safeguarded,” said Potok.

Highly restricted data, she explained, include data collected by the Census Bureau, tax data, and other statistical data collected under a pledge of confidentiality according to the Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act of 2002. This law includes many legal restrictions on how such data can be shared, and it requires a proposal, a background check, and being sworn in as a special agent, Potok explained. “This is not at all like some of the things I have heard described [at this workshop], which is basically a free-for-all, where if you can collect it and sell it, go for it regardless of anybody’s privacy protection,” she said. Aside from being alarmed by this type of “make it up as we go along” system, Potok is also concerned about the quality of data being released by those systems. “I come from a system where we consider official federal statistics to be the gold standard in quality,” she said. “It may not be 100 percent perfect, but it probably is as close to the truth as you are going to get with some of these data.

There is, however, one growing problem in the federal statistical system: people do not want to answer surveys anymore, and administering surveys is getting more expensive at a time when federal budgets are being cut. At the same time, the demand for high-quality data at a more granular level and on a more timely basis is stressing the system because putting out a national indicator based on a small sample size is not good enough anymore. One concern for her is that, as the federal statistical agencies move more toward combining data, they are buying data from commercial sources and combining it with government records. This raises questions such as how to determine the quality of those data and how to talk about it in terms of fitness for use. Research by the federal government on commercial data sets has shown that the quality is bad compared to official government data. Commercial data, she said, are often not complete and have built-in biases.

Addressing the issue of bias, Potok used the American Community Survey as an example of the difficulties that arise when trying to combine data from different sources. This survey, conducted by the Census Bureau, determines how the federal government distributes some $800 billion a year to states and local governments. In an attempt to shorten this comprehensive survey, the Census Bureau has been researching the possibility of substituting commercial data about the value of houses, mortgages, and assessments for survey questions. What the Census Bureau found was that commercial data are sparse in rural areas because there is not much profit motive to spend time collecting rural data. In addition, some states do not have automated databases, so entire states were missing from the

commercial data. As a result, the commercial data and survey data were inconsistent, creating the challenge of how to resolve those inconsistencies when private companies do not have to share the algorithms they used to calculate housing values and other measures and the biases they introduce through the use of those algorithms. “The challenge is to get a private company to reveal proprietary algorithms so you know what the bias is, because if you know what it is, you can start to deal with it, but if you never see it and do not understand it, you do not know what is in your data,” Potok explained.

What worries her is that people will try to bypass official statistics and buy data that have not been well curated or collected using standard quality measures. Potok said she knows of at least two companies that are working to put all the data in the world into an open-access cloud with no curation whatsoever. While some people may try to intentionally corrupt data sets, her fear is that the databases will be corrupted simply because the quality of the data being put into them is poor and that those data will be used to develop bad public policy and draw incorrect conclusions with important public impact. Her recommendation to the workshop was to look at the existing, mature federal framework for statistical data to see if some of its features can be adopted for the open data environment.

Engaging in Good Data Management Practices

In the ensuing discussion, Pelton commented on the massive amount of data being generated and the difficulty in getting useful information from those data and on ensuring the quality and curation of those data. Stall agreed and said one of the tasks she is undertaking is to make researchers aware of what good data management entails. “It is not part of their curriculum, and if they get data management skills it is because they were sitting next to someone who was telling them what a good way was to manage their data and what was not,” said Stall. One advantage Earth and space science projects have in this realm, because they generated enormous data sets by their very nature, is that their data management aspects are well funded. She is concerned, though, about studies that are generating smaller data sets, that include multiple-data-type datasets, and that may not have the resources to engage in good data management practices.

Perakslis said that what people have to understand is that the very nature of data is changing. In his opinion, the words “dirty data” should be banned, with the term “wild-type data” substituted because that is what those data really are. In the clinical trial world, for example, biostatistics has not changed since the best computer available was the slide rule, and those statistical methods cannot account for exceptional responders, targeted therapies, and other new models of disease therapeutics. What this means, he said, is that while precision, standards, and quality are important, those measures must be put in context of the data being examined.

The discussion also brought up the matter of what to do when federal law prohibits federal statistical agencies from collecting certain data, such as on firearm ownership or religion. Potok said the hope is that credible, high-quality research institutions that do solid work will collect such data. In fact, the Pew

Research Center, for example, conducts a large religion survey and is transparent about how it collects, manages, and analyzes the resulting data.

Several participants ended the discussion session by putting questions on the table for further discussion at a later time. One question asked was whether it was possible to do more to make sure that humanitarian data, since they do not go through the normal channels of collection, are made available for appropriate use. A second question concerned the quality filters used to put data into repositories and how they can be developed to ensure that the data are of high quality.

SHARING RESPONSIBLY: DATA ETHICS IN PRACTICE

Data are foundational to contemporary science, and there are many legal, regulatory, and methodological challenges to using data that the previous speakers had described. The most important challenges, argued Madeleine Murtagh, professor of sociology and bioethics at Newcastle University, are those associated with the people who generate and use data. “It is the peopled nature of data sharing that introduces the greatest complexity, regardless of what discipline or sector we are in,” said Murtagh. That, she said, is where data ethics come into play.

While the 2004 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development declaration on access to research data from public funding calls for full and open access to scientific data should be the international norm, there cannot be unfettered open access to human data, said Murtagh. Human data are sensitive data, not only when they come from humans as direct subjects of research, but also when doing small-area geography, as Simson Garfinkel noted in his presentation. “We know from our statistical colleagues that pseudonymization, de-identification, and anonymization are highly problematic, because the minute you start triangulating, the minute you start inferentially comparing data, you have problems of identification,” she said. “We do need to have the right to choose when and where our data gets used, how we take it back, and how it gets erased.” She also pointed out that an individual is not just his or her data.

Data sharing cultures today are necessarily interdisciplinary, intersectional, and, Murtagh would argue, in need of including some element of public engagement. Many biomedical studies, for example, cannot use the existing small studies because their statistical power is not big enough. “We have to share to make findings, especially when we have got small-size effects such as with rare diseases,” she said. The problem in sharing across disciplines is that they come from different epistemic cultures; that is, they have different ways of understanding how the world works and what constitutes data. Similarly, sharing data across sectors involves dealing with different policies and practices from diverse cultural backgrounds. Addressing epistemic and practice differences requires conversations, sometimes thorny ones, and working together to understand and bridge those differences, said Murtagh. These conversations, however, need to involve an often-neglected sector, the public.

Speaking from a philosophical point of view, Murtagh said that if communities and disciplines and sectors are connected, it is predictable that there will be

interactions and those interactions will inevitably shape how individuals behave. Philosophers talk about entanglements, and when it comes to ethics, legal, technological, social, and economic factors are irrevocably entangled. She asked the workshop participants to keep that idea in mind as she presented some examples of data ethics in practice.

There is a framework for responsible data sharing developed and published in 2014 by the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH) that is similar to the General Data Protection Regulations. This framework, the GA4GH Framework for Responsible Sharing of Genomic and Health-Related Data,4 aims to activate the right to science and the right to recognition for scientific production by promoting responsible data sharing. In contrast to other frameworks that are based on the principle of protection from harm, the GA4GH’s framework is based on an interpretation of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Knoppers, 2014; Knoppers et al., 2014). Entrenched within this declaration is a right to have access to the benefits of science, a right for those who develop that science to be recognized, and the duty to the community. “When we are talking about data, we are often talking about individual data, but we are also, as we have heard at this meeting, talking about communities and populations and the impact is more broad than simply at the level of the individual,” said Murtagh. In the context of responsible sharing of genomic and health-related data, these rights translate into the principle that advancing science is an ethical contract that researchers have signed, and they lead to the core elements for responsible data sharing, which include

- transparency;

- accountability;

- data quality and security;

- privacy, data protection, and confidentiality;

- risk-benefit analysis;

- recognition and attribution;

- education and training; and

- accessibility and dissemination.

In addition to ethical frameworks, there are technical solutions, such as DataSHIELD, a privacy-protecting statistical software package that takes the analysis to the data instead of moving the data (Gaye et al., 2014). As Murtagh explained, this approach leaves data on the server where they are produced or archived and lets the analysis happen behind that server’s firewall, which has several advantages. Because this software only pulls out summary statistics and not the original data, disclosure is unnecessary. In addition, this approach allows data

___________________

4 Available at https://www.ga4gh.org/ga4ghtoolkit/regulatoryandethics/framework-forresponsible-sharing-genomic-and-health-related-data/ (accessed May 30, 2018).

from countries that prohibit it from leaving national borders to be useful for advancing science, and it can coordinate parallel analyses of multiple data sources. “We are not trying to get around ethics by doing this but finding another way of looking at how you do ethics,” said Murtagh.

One major problem with the approach is that current governance structures can prevent it from happening. In a project called BioSHARE, Murtagh and her collaborators conducted a proof-of-concept experiment using this approach. The statistical analysis came out with the exact same result as when the analysis was performed in the traditional manner, but when they tried to put it into practice, current governance mechanisms would not allow it (Murtagh et al., 2016). As she noted, “I think that the very big hurdles in science are human hurdles, human relationships, and problems that have nothing to do with the science.”

Another effort in which Murtagh has been involved is the Managing EthicoSocial, Technical, and Administrative Issues in Data Access (METADAC) program that looks at data access for multiple studies. METADAC is an independent body for granting access to longitudinal research projects in the United Kingdom that use phenotypic and genotypic data and associated sample collection. This is an example, she said, of where humans need to make decisions, and in this case those humans include common citizens. The METADAC Access Committee assesses sensitive data and sample applications and it operates on the principle that governance of complex data requires expertise from across domains and disciplines, including that of study participants. Committee members, said Murtagh, include bioscientists, social scientists, clinicians, lawyers, ethicists, and participants in longitudinal studies. Citizens are involved to get their views and bring their experiences as study participants into the decision-making process and to develop policies that help ensure achievable, reasoned, and responsible decisions (Murtagh et al., 2018).

In fact, said Murtagh, bringing participants into the decision-making process has helped the committee make different—and better—decisions and do a better job of communicating with the public. One of the most important criteria the committee now uses to decide if it going to approve access to the data from a longitudinal study is whether doing so will upset or alienate the participants in the study. “That is an absolute bottom line, but we are not in a position as the professionals to make those decisions,” she said, and that is where someone who has participated in a study can bring expertise and perspective to bear on the approval process.

Murtagh’s final example of data ethics in action was the Great North Care Record (GNCR), an approach for making data in the United Kingdom’s health system appropriately accessible for individual health care, service planning, and research. She noted that while most people in the United Kingdom believe that their health record data are accessible no matter where they are in the country, that is not the case because the data are in silos at different institutions. While data sharing across health care facilities would help deliver better care, data sharing would also benefit researchers, too. For that to work, though, the population must trust the researchers and be comfortable with having their data shared. GNCR is

building trust by engaging with people through surveys, engaging with outreach activities designed to reach vulnerable, hard-to-reach, and underserved populations, and involving them in governance and decision making. Murtagh noted that 96 percent of the general practitioners in the region covered by GNCR have signed up to participate in the project. The technology behind GNCR is being rolled out at different scales to see how to make it work across the entire region.

In closing, Murtagh said, “If you are serious about people’s involvement, get them making decisions. But even more so, we want to go upstream so that we are creating trustworthy technologies and infrastructures for data that people are happy with, and one of the ways you do that is to co-produce it with them.” She describes this as a sociotechnical approach to data governance, data ethics, and making data more usable. “Sharing data responsibly is not simply made up of, but I would argue absolutely requires, interdisciplinarity, intersectionality, public engagement, and entanglements, and even if they are sometimes thorny entanglements, we still need them,” said Murtagh.

In response to a question about how citizen science fits into the ethics of data access, Murtagh said there is a project under way in the United Kingdom that will use DataSHIELD to allow citizens to access aggregated data on young people’s sexual health and enable them to do some real science. In her opinion, this approach of having a controlled mechanism of access, with rules about data access and publication and a committee to approve access, is preferable to providing access through legal means such as a freedom of information request. The goal will be to grant data access and allow citizen science in a thoughtful and responsible manner, she said.

EQUITY, SUSTAINABILITY, AND PRIVACY

The final session of day two featured two presentations, from Cheikh Mbow, Executive Director of START, and Roger-Mark De Souza, President and Chief Executive Officer of Sister Cites International. An open question-and-answer period, moderated by Andreas Rechkemmer, professor and American Humane Endowed Chair of the Graduate School of Social Work at the University of Denver, followed the two presentations.

Domination or Dependence for Data Collaboration in Africa

When START was founded some 25 years ago, its mission, said Cheikh Mbow, was to ensure that science is infused into society in the developing countries of Africa and Asia. That mission continues today, now augmented by the need to package and deliver to developing countries the capacity to deal with and make use of the enormous quantities of data available to further the goals of sustainable development. Doing so requires addressing ethical issues involving data ownership, data sharing, and data disparities and power relationships between the global North and South.

Ethics, said Mbow, are closely tied to culture, and cultural differences influence the way communities think about the ethics of data collection, storage, and sharing. There is common ground, though, among all ethical cultures, which is to never do harm and always give back. Generosity, he said, is an intriguing personal characteristic of scientist, but a scientist must be generous because science that is not shared does not exist. “Everything you keep to yourself is nonexistent,” said Mbow. “It only exists when people can use the information you have.”

Ethics and data interact in multiple spheres, he said. The legal and administrative sphere considers which kinds of rules matter and which kinds of regulations regarding data collection are appropriate. In the political sphere, ethics plays a role in determining who makes decisions about the types of data that can be collected and which interests are involved in the decision-making process. In some African countries, for example, there are types of data that are politically sensitive and thus difficult to collect. In addition, the political powers in some nations will try to control the type of data that needs to be collected. “There is this tension in the political sphere that always orients the way we collect data, the way we use data, or the way we speak about data, and the comfort of disclosing sensitive information or the discomfort of not saying it,” said Mbow.

In the natural science sphere, there is the tension between people who want to protect the indigenous natural resources and those who want to make discoveries from those resources, patent them, and not share the intellectual property or associated economic benefits with the people who have protected those resources for centuries. In the technological sphere, a tension exists between indigenous people who want to preserve local forests, for example, and those who want to use technology to develop and harvest those resources. “You can see that the issue of just collecting data is influenced by many other factors that will expand the scope of the ethical analysis if you want to include them, and it is important to do so when it comes to the developing countries in Africa,” said Mbow.

Science, however, is not only created using data, he said. Science requires a budget, and it requires the ability to store data, manage it, and make it both interoperable and accessible. The latter is a prominent issue in Africa, where penetration of the internet is only around 35 percent and penetration of mobile phones has remained at around 30 percent for the past 20 years. As a result, the assumption that data will be freely accessible just because they are in a cloud somewhere is likely not to be accurate for every African nation. Science also must balance the desire to do research on a particular subject and the aspirations and needs of a community, and it needs to consider areas that are understudied and where data are scarce, such as in the Sahara or Deep Congo Basin. “Scientists do not always collect data where data are needed,” said Mbow. “They collect data where it is possible to collect data.”

Africa is a large continent, one that would fit the United States, China, India, Japan, and much of Europe within its borders, and Mbow questioned who it is telling the story of Africa and who gets the data. Most of the data relevant to

Africa exist outside of the continent, and that disparity continues despite the efforts of several governmental and nongovernmental organizations, including the U.S. Agency for International Development and the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development, which are trying to support capacity building for domestic data collection and use. Mbow recalled how when he was asked to design the layout of the Great Green Wall of the Sahara and Sahel Initiative, an African-led project to combat the effects of climate change and desertification, the only place that he could find productivity data across Africa was at the U.S. Geological Survey, which readily shared the data with him. In fact, he said, it was easier to get those data than the small amount of data existing in various African institutions. “The issue is not the tension between North and South,” he said. “It is about the way data are organized in different parts of the world and how those data are used in the African continent.”

Mbow noted that less than 1 percent of the world’s research output comes from Africa, which is home to 12 percent of the global population. Based on numbers of publications, Europe and the United States dominate science in Africa, though most publications on research in Africa do include an African collaborator. One observation he made is that collaboration rarely occurs among African scientists from different countries or different regions on the continent. One reason for this is that there is value to African scientists to be affiliated with researchers or institutions from outside the continent, something that shows up in the number of students who travel abroad to get their Ph.D. China has taken over from the United States as the country African students are most likely to go to for their Ph.D., part of China’s efforts to build soft power through data and the partnerships that result between a graduate student and the host country.

What this means at the local level, said Mbow, is that it stifles the development of building research capacities in Africa and leaves such efforts dependent on countries outside of the continent. It also means that data continue to be generated in Africa but reside outside of Africa. Data and knowledge mean power, and thus the struggle to have data is inherently a political one, said Mbow. To address the current power imbalance, researchers from the developed world need to engage users to identify what data they need to serve the interests of their communities. Perhaps more important is the need to help local researchers and other groups in communities develop and learn how to use the tools that turn data into knowledge and innovation and that ensure access by all to the fruits of knowledge mobilization and innovation. As part of this effort, it is important to minimize what Mbow referred to as the data fatigue that results from communities being asked to collect data for which they have no idea what it will be used or how it is relevant to their information needs.

Regarding the issue of investing in data collection, it is necessary to consider where the money is coming from and where it is invested. In his opinion, it is important not just to fund data collection, but to create connections between the funder, the national government, and the local communities that will serve as the data source. Such connections are vital, he said, to ensure that data are benefiting those communities and enabling them to innovate for their own good.

Mbow pointed out that global data, such as satellite-generated vegetation maps, are useful for conceptualizing problems and workable solutions, but when it comes to action on the ground, data with much finer granularity are needed. Communities, he explained, need to know how their villages are being influenced and will be affected by a project. He noted that there are programs in Africa now that are trying to move from the satellite scale to the village scale, but the challenge is mobilizing the human resources to collect data in different portions of the continent.

On the subject of data governance, Mbow said governance requires multiple connections among many partners and countries, and forming those connections, particularly with countries that have no data governance policies, can be difficult. He also commented that countries produce data in different formats, making interoperability a significant challenge and a barrier to multinational collaboration. His message to the workshop was that data operations must be built in a way that manages ethics, governance, and open data policies from the very start. Toward that end, START is engaged in the Partnership for Resilience and Preparedness to help visualize and customize data, improve access to data through good governance and open-access platforms, and thereby support the climate resilience ecosystem.

Mbow concluded his presentation by recounting something he was told by a friend, which is that at times, the role of local researchers in the developing world is often reduced to that of a tourist guide in that they help negotiate and open the physical and cultural terrain rather than conceive of projects or contribute equally. Local researchers accept this role, perhaps because the resources and facilities otherwise available to them do not allow them to rectify the imbalances of privilege. For them, the choice then becomes one of being the last author on a paper or not being an author at all. “There are many solutions we can envision when we talk about data and ethics in that perspective,” said Mbow. I hope that some of them will be implemented with unrelenting diligence.”

Perspectives on Data, Cities, and Resilience

Sister Cities International, explained Roger-Mark De Souza, focuses on matching cities, states, and counties looking for areas of commonality that will serve as a basis for engaging what the organization calls citizen diplomats. In that regard, questions of data use, privacy, resilience, and sustainability are at the heart of much of what the organization does. Cities, he said, have been using technology and data to manage urban congestion, maximize energy efficiency, enhance public security, allocate scarce resources based on real-time evidence, and even educate their citizenry through remote learning. Today, though, the concept of the data-driven “smart city” is evolving as a radical new approach to remedy urban problems and make urban development more sustainable (Paskaleva et al., 2017). One concern of his is that experimentation with future internet technologies, cloud computing, and the Internet of Things has been led by commercial enterprises and

research centers, with less involvement from external stakeholders such as citizens and decision makers. However, realizing urban sustainability goals depends on the direct participation of local actors and stakeholders in the process of thinking, defining, planning, and executing social, technological, and urban transformations in smart cities.

Mayors, said De Souza, are seeing a unique opportunity to mobilize themselves to form networks with their fellow mayors to use data for sustainability purposes. They also credit themselves with playing an instrumental role in securing a dedicated goal on inclusive and sustainable cities in the United Nation’s 2030 Agenda and sustainable development goals. Since then, he added, hundreds of local leaders have committed to supporting these sustainable development goals in their cities. Sister Cities fits into this effort through its ability, demonstrated over its 62-year history, to bring together people from different countries in an atmosphere of mutual respect, understanding, and cooperation.

The programs Sister Cities engages in involve scientists, volunteers, nonprofit organizations, civic groups, and business, and they build on arts exchanges, data exchanges, technology innovation, health, and disaster mitigation from the perspective of looking at how cities can learn from one another. Sister Cities has 500 U.S. members, and is engaged in more than 2,000 projects in partnerships with municipalities in 142 countries on six continents. As an example, De Souza discussed a partnership between San Francisco and Cork, Ireland, that links middle and high school students and computer coding experts to exchange coding insights in the context of other science, technology, engineering, and math activities. In this project, Irish students taught peers at a school in San Francisco how to code and learn from senior engineers in the coding field.

A 10-year collaboration between San Diego and Jalalabad, Afghanistan, operates computer labs at 18 high schools in Jalalabad, where students receive training in information technologies and English. Students in the two cities connect with each other through Skype and Facebook. All told, the program has directly engaged over 6,200 boys and over 5,200 girls, along with an additional 9,000 observers. A project linking Austin, Texas, and the Borough of Hackney in the United Kingdom features cross-cultural and cross-functional teams working together and receiving joint training on marketing, research, and prototyping. British Airways brought the student teams from Hackney to Austin to pitch their final solutions to the business community at a pop-up venue established during the SXSW Festival.

Not all projects involve students, though. For example, in May 2013, the mayors of Paris and San Francisco signed a memorandum of understanding to support joint research programs on smart city technology, serve as experimental sites, and share data from these experiments. Projects under way include one that looks at mobility in the two cities, the data being collected around that, and how those data can be used to help citizens make commuting decisions. Other projects are looking at how homebuyers can use technology to help with their search for a new house, how a combination of ride-share services and public transportation can shorten commutes and ease congestion, and how technology can help moms

find kid-friendly locations in the city and individuals with disabilities find accessible public spaces.

In February 2018, Sister Cities hosted the first Mexico–United States Mayors’ Summit that brought 30 mayors from each of the two countries and 300 other participants to look at several issues, including technology transfer across borders. The summit brought together technologists, entrepreneurs, disrupters, and some of the best hackers from the two countries to compare notes and discuss data use and privacy issues.

What has come from discussions such as these, said De Souza, is that mayors are looking at how they can harness new data sources, such as mobile phones and geospatial technologies, to inform their policies and budget allocations and make progress on meeting the sustainable development goals put forth by the United Nations. He noted that philanthropic organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and other donors are already increasing the capacity of local governments to use new and existing data sources to support evidence-based policies and interventions. From a political economy framework for data-drive governance, there is a problem and data to address the problem, and what is needed is governance regarding permissions, privacy, and incentives for locally elected officials to access, analyze, and apply the data to inform policy decisions (Edwards et al., 2016).