6

Investing in National Preparedness Initiatives Against Microbial Threats

During session II, part A, of the workshop, speakers explored the challenges and opportunities of investing in national preparedness initiatives to counter future microbial threats. The session was moderated by Beth Cameron, vice president for global biological policy and programs at the Nuclear Threat Initiative. She provided opening remarks, highlighting the importance of investing in preparedness to counter infectious disease threats to avoid the high costs of outbreak response. There has been some progress in preparedness efforts, as several countries have strived to implement capacities to boost preparedness by complying to international preparedness instruments including the International Health Regulations (IHR) and the Performance of Veterinary Services (PVS) Pathway; furthermore, the global community has begun to understand the cost of preparedness through the Joint External Evaluation (JEE).1 However, she said there are several gaps that need to be filled to achieve robust preparedness at the country level and around the globe and hoped that the presenters would illuminate opportunities to overcome these challenges.

The session began with a review by Tolbert Nyenswah, director general of the National Public Health Institute of Liberia, of Liberia’s experience

___________________

1 The IHR is an international agreement that is legally binding on 196 of the World Health Organization’s member states. The aim of the IHR is to help the global community to prevent and respond to public health events that may have international consequences. The PVS Pathway, developed by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), aims to sustainably improve the compliance of a country’s veterinary services with OIE international standards. The JEE is a voluntary, collaborative process to assess a country’s capacity under the IHR to prevent, detect, and rapidly respond to public health threats.

building microbial threat preparedness capacities through the development of a national action plan. Andreas Gilsdorf, consultant on public health security, then described the challenges and opportunities of implementing the IHR and investing in outbreak preparedness and response. Franck Berthe, senior livestock specialist at the World Bank, followed with a discussion on the PVS Pathway to help facilitate investments for preparedness that affect health systems. Finally, Katherine Lee, assistant professor, Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology, University of Idaho, reviewed the economics of implementing a One Health approach to address microbial threats.

EPIDEMIC PREPAREDNESS: LESSONS FROM LIBERIA

Tolbert Nyenswah, director general of the National Public Health Institute of Liberia, shared his experiences with strengthening epidemic preparedness capacities in Liberia. He discussed the country’s response to recent infectious disease epidemics and their economic impact, and he highlighted the importance of investing in national action plans to prepare for microbial threats.

Economic Impact of Ebola and Other Infectious Diseases

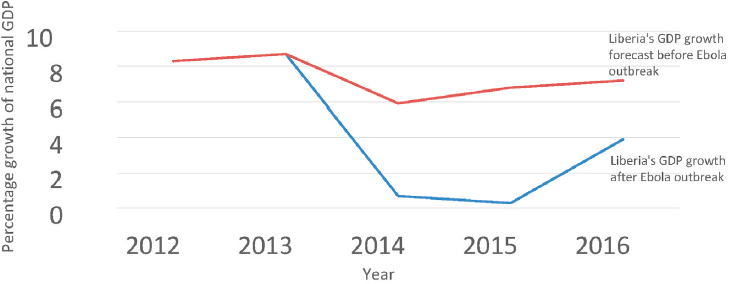

The Ebola outbreak significantly affected trade, travel, and health service delivery in Liberia (CDC, 2016a). Nyenswah reflected on the outbreak’s consequences, including school closures, hospital closures, airline disruption, reduced economic activity, and social isolation. The World Bank has estimated the economic impact of Ebola for Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone amounts to $2.8 billion (World Bank, 2016). He noted that prior to 2014, Liberia experienced nearly double-digit growth in its gross domestic product (GDP). The outbreak, combined with falling global commodity prices, led to a reduction in annual GDP growth to less than 1 percent (World Bank, 2015b) (see Figure 6-1). He added that the economic impact is outlasting the epidemiological effects in the region and that Liberia is still having difficulty recovering from the crisis, particularly with stagnation in the mining and service sectors.

Since the Ebola epidemic, Liberia has experienced additional outbreaks of several other infectious diseases, including measles, Lassa fever, meningococcal disease, and monkey pox, a disease that had not occurred in more than 20 years. Specifically in 2017, Liberia experienced 39 different outbreaks, three of which required a humanitarian response (NPHIL, 2017). In April 2017, there was a bacterial meningitis outbreak, which many people feared was a reintroduction of Ebola, but with the help of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Liberian govern-

SOURCES: Nyenswah presentation, June 12, 2018; data from World Bank, 2015b.

ment responded to it swiftly (Patel et al., 2017). He argued that despite having controlled these outbreaks, the economy of the country was affected.

Strategic Planning for Epidemic Preparedness

Nyenswah described Liberia’s progress on epidemic preparedness and the importance of national action plans to enhance health security. He explained that national action plans based on global or regional initiatives are subject to routine internal and external assessments based on established metrics such as those outlined in the Global Health Security Agenda Action Packages and JEE tool. National action plans, he added, should engage players across multiple sectors to ensure alignment of individual sector activities and crosscutting activities with national priorities. These plans should also include simulation and training activities to avoid loss of historical memory or complacency among rapid response teams caused by staff turnover and infrequency of outbreaks, he said.

Nyenswah explained that in Liberia the training package for the standardized rapid response teams incorporates strategies from the national epidemic preparedness and response (EPR) plan, the National Technical Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response guidelines, as well as lessons learned from the Ebola crisis. This package was used to train hundreds of rapid response team members at the national and district levels in 2016. While this type of training is an important step toward a standardized approach for the management of major outbreaks, he repeated that the national EPR plan requires regular refresher training and simulation exercises to sustain efficacy.

An additional benefit of national action plans, Nyenswah noted, is to help identify how to balance preparedness needs with resource constraints. When new activities to address national priorities for preparedness are added to the action plans, they can be mapped to existing opportunities, and where appropriate, leverage resources from across different projects and sectors. The Field Epidemiology Training Program,2 through the African Field Epidemiology Network and CDC, has been successful in preparedness planning in some of the districts in Liberia, he added.

Nyenswah described the importance of integrating the One Health approach in the national action plan.3 He noted that Liberia has made progress with implementing this approach with the development of a national One Health Coordination Platform in 2017. This platform sets out to coordinate and ensure multisector participation, resource mobilization, accountability, and transparency at all levels. This platform, he added, has facilitated the development of strategic operational and costing plans for rabies prevention and control and antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Nyenswah stated that as part of its One Health approach, Liberia has also prioritized adherence to the PVS Pathway, focusing on animal vaccines and medicines, veterinary laboratory services, and livestock officer training. The pathway has led to the creation of Ministry of Agriculture offices at the district level, better coordination between country-level agriculture officers and district level staff, and formal partnerships with private veterinary providers.

POTENTIAL CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR INVESTING IN NATIONAL-LEVEL PREPAREDNESS

Andreas Gilsdorf, consultant on public health security, described the challenges and opportunities for investing in preparedness initiatives to counter infectious diseases through the lens of monitoring and evaluation of the IHR. He noted that despite the growing body of knowledge on the economic impact of microbial threats, policy makers are not doing enough to address the issue.

Challenges for Investing in Preparedness Initiatives

Gilsdorf presented several challenges that inhibit adequate action to strengthen outbreak preparedness and response. He noted that while the

___________________

2 The program trains field epidemiologists around the world, giving them critical skills to collect, analyze, and track data to prevent infectious disease outbreaks.

3 One Health is “a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary approach—working at the local, regional, national, and global levels—with the goal of achieving optimal health outcomes recognizing the interconnection between people, animals, plants, and their shared environment” (CDC, 2018).

IHR is the most important legal framework on global health security, the specific details presented in the IHR are open to interpretation and lack precision on priorities, making it difficult to use the document as a tool to catalyze national preparedness and response. Many of the IHR targets have a long timeline, which is not attractive to policy makers, also making its implementation challenging. Additionally, Gilsdorf pointed to the issues of making the investment case for prevention, such as the difficulty to measure what was avoided, and the high startup cost to pay for staff and equipment. Moreover, funding for these initiatives is typically not coordinated, nor is it necessarily embedded in the national planning cycle, he said.

Gilsdorf highlighted the multitude of organizations and tools involved in national preparedness efforts. There are many donors involved, each that tend to have their own particular perspectives and interests. He argued that although different tools such as the JEE and PVS are useful, they often overlap and have separate implementation approaches that can lead to different recommendations. This further creates a challenge for policy makers trying to choose a way forward.

Multisectoral Coordination for Preparedness

Because of the multiple players in preparedness efforts, Gilsdorf emphasized the need for multisectoral coordination within government agencies, across international organizations, and with the private sector, as well as high-level political commitment and supporting legal structures. He highlighted that the involvement of the private sector is particularly needed for better exchange of information and better use of limited resources. While this coordination can be difficult, it can lead to better and more sustainable results.

Gilsdorf noted that existing mechanisms could be leveraged or new ones could be created to facilitate coordination among different groups. He highlighted the importance of having the relevant players meet with one another on a regular basis to better understand each other’s aims and needs. On the operational level, setting up joint emergency operation centers could allow stakeholders across and within agencies to be better coordinated as well as run everyday operations in between outbreaks, and does not require investing in any specialized equipment.

He also noted the importance of joint outbreak investigation teams and simulation exercises conducted by multidisciplinary teams, where roles and responsibilities are distributed across teams, which builds trust and understanding. He shared his experience participating in a tabletop simulation for Group of Twenty health ministers in 2017. The exercise helped to create awareness among leaders of the consequences of implementing an adequate and effective response during major outbreaks. He concluded that while

preparedness initiatives and multisectoral collaboration can be expensive, they are worth the investment. He reiterated the need for moving toward a multisectoral collaboration approach with better understanding of the perspectives of the different stakeholders involved.

USING THE PERFORMANCE OF VETERINARY SERVICES PATHWAY TO BOLSTER PREPAREDNESS

Franck Berthe, senior livestock specialist at the World Bank, discussed the PVS Pathway and its implications for strengthening health systems. He began by describing a recent outbreak in Burundi of peste des petits ruminants (PPR), a viral infection affecting small ruminants such as goats and sheep (OIE, 2018a). He noted that the World Bank, working with its partners at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and OIE, were able to quickly assess the needs and launch a successful vaccination program because of the country’s strong health and veterinary service networks.

Performance of Veterinary Services Pathway

The PVS Pathway is a cyclical process made up of four phases that aim to sustainably improve a country’s veterinary services by addressing food safety, veterinary medicine, antimicrobial resistance, zoonotic diseases, laboratory infrastructure, and human resources (OIE, 2018b). Berthe described the four phases of the process. First, the orientation phase provides information and lessons on veterinary services generally as part of regional or subregional workshops, which are valuable as they bring together countries with common interests and shared challenges. Next, the evaluation phase uses the PVS evaluation tool to assess country-level resources and capacities, as well as additional follow-up and more narrowed focus tools such as the PPR tool. The planning phase includes the PVS gap analysis, which determines and confirms the country’s veterinary service priorities and helps to develop an indicative costing of the resources required for the implementation of the activities identified (see more details in the next section). Finally, the targeted support phase consists of supporting the implementation of the actions identified in the planning phase and linking interventions with JEE and PVS recommendations. Berthe shared examples of targeted support activities including assisting countries on drafting legislation, integrating services through a One Health approach, providing laboratory support, and veterinary professional education.

Berthe presented examples from Thailand and Ethiopia that illustrate country responses to the PVS evaluation and the PVS gap analysis findings. In Thailand, PVS results from 2012–2013 were used to successfully advo-

cate for a 13 percent increase in the budget of the Department of Livestock Development, recruit additional veterinarians, create a new government agency division focused on livestock feed safety, and develop new regulations on animal welfare and food product manufacturing (OIE, 2018b). In Ethiopia, the findings from the PVS gap analysis in 2012 led to the creation of a mobile phone-based animal health information system, improved reporting on animal processing facilities, and a road map to improve veterinary services (OIE, 2018b).

Performance of Veterinary Services Gap Analysis

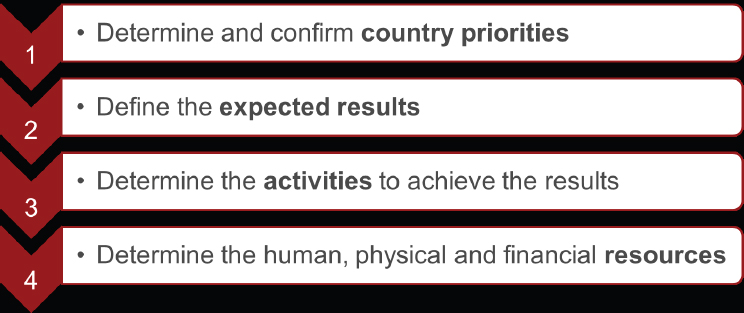

Berthe described the four steps for implementing the PVS gap analysis (see Figure 6-2). Step 1 is the determination of the country’s high-level priorities across five pillars: livestock development and trade, animal health, veterinary public health, laboratories, and management. During this step, countries have the opportunity to decide on their priorities for policy development by identifying two to four priority areas within each of the five pillars. Step 2 involves defining the expected results by setting critical competency target levels for the next 5 years. The PVS tool scores countries on a scale of 1 to 5, so Berthe noted that countries decide the score they want to achieve within the 5-year timeline. Steps 3 and 4 include developing a plan of activities under each critical competency and determining their costs using a spreadsheet tool that links the activities to a costing database. The most important outcome of this analysis is the development of a 5-year

SOURCE: Berthe presentation, June 12, 2018.

budget for veterinary services with operational and investment components, he concluded.

According to Berthe, 115 out of 181 OIE members have requested PVS gap analysis, and 95 countries have actually gone through this process. However, only 22 of these reports are publicly available on the OIE website, and an additional 37 reports have been shared with the donor community and development partners. He noted that making these reports public is critical as these results are not only relevant to the country itself but can also be used by other countries or agencies when designing national or regional projects.

Berthe shared an example of the World Bank Regional Sahel Pastoralism Support Project that invested $50 million in Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, and Senegal toward animal health initiatives (World Bank, 2015a). The project includes activities to upgrade the infrastructure and capacities of national veterinary services and support surveillance and control of priority animal diseases. These investments were selected based on the PVS analyses previously conducted in these countries. Beyond a domestic exercise, Berthe concluded that the PVS Pathway and gap analysis tool guide the design and implementation of investments to strengthen veterinary health systems toward compliance with international standards. The PVS findings have revealed how chronically underresourced veterinary services are in many countries. He added that the PVS Pathway is a shift away from the short-term, vertical, single disease programs approach.

COSTS AND BENEFITS OF IMPLEMENTING A ONE HEALTH APPROACH AGAINST MICROBIAL THREATS

Katherine Lee, assistant professor, Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology, University of Idaho, described the costs and benefits of the One Health approach to microbial threat preparedness. She began her presentation by laying out three questions that need to be addressed to understand the economics of microbial threats and One Health: What is the value of managing infectious disease threats? When should we invest in management? How should we build the management framework to cost-effectively address these risks? Within this framework, she said the question is then if there is a place for One Health to cost-effectively approach some of these emerging infectious diseases.

Understanding the Value, Timing, and Strategy to Counter Emerging Infectious Diseases

Over the past 50 years, zoonotic infectious disease outbreaks have increased in frequency and severity (Jones et al., 2008). These outbreaks

are increasing in relation to rising agricultural intensification, globalization, and changing patterns of interactions between humans and food sources. Lee explained that these outbreaks are associated with significant economic impact and thus there is value in investing in the management of them, especially through early detection and rapid response, to change the trend of increasing emerging infectious diseases. She highlighted the opportunity for the One Health approach to reduce and mitigate zoonotic outbreaks by targeting interventions on both wildlife and livestock.

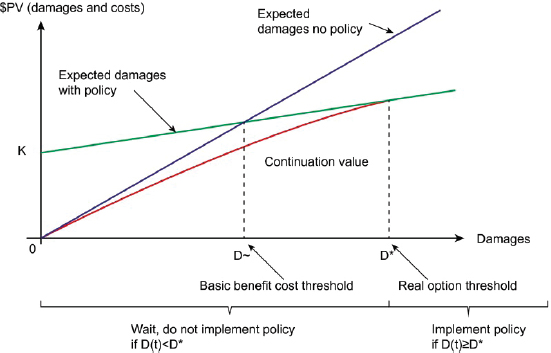

Because these risks are dynamic, the timing of investments is also important, and economic analysis can determine the value of investments made at different points in time (see Figure 6-3). She noted that early investments in outbreak prevention are more cost-effective than later investments in outbreak response (Pike et al., 2014). However, she cautioned that there is a threshold where the expected damages for the projections of future events exceed whatever the returns are from investing in a preventive framework or an early response framework for managing these risks. While it is important to take time to evaluate options and strategies, according to Lee, “Investing early is investing better. But we better not wait too long to sort this out.”

Once there is understanding about how timing fits into the problem, Lee stated the final question is how to design policies to effectively address the risks. Lee presented research that examined how the $5.4 billion the United States appropriated to the 2014–2016 West Africa Ebola epidemic

NOTE: D = damages; K = cost; PV = present value.

SOURCES: Lee presentation, June 12, 2018; Pike et al., 2014.

response could have been spent—either to prevent the outbreak from happening or to rapidly respond to the outbreak by mobilizing capital and labor to the source of that outbreak and mitigate the damages (Berry et al., 2018). The study found that an upfront investment of about $1 billion in mobile capital, a global network of laboratories, and highly trained surveillance teams placed in high-risk areas around the globe would serve as insurance against continuous threat of emerging infectious diseases. This network would employ best management practices and respond quickly to outbreaks as they occur, resulting in savings of more than $10 billion in reduced costs from avoiding expected future emerging disease impacts. Therefore, she argued that this option would be better than waiting for an outbreak to occur and spend millions in response.

One Health and Land Use

Lee moved on to describing how to better address emerging infectious disease threats through a One Health approach. She said one way to think about this is through examining other overlapping global issues such as land use changes, specifically surrounding land conversion for industrial purposes versus conservation efforts. According to Lee, greater land conversion is associated with more frequent interactions with wildlife, and therefore an increase in emerging infectious disease outbreaks. While the benefits of land conversion are clear—namely economic growth and job creation—further research is needed to evaluate the costs, which include loss of carbon storage, loss of wildlife habitats, and higher disease incidence, she said. Lee argued that the topic of land use requires quantifying and assessing trade-offs as well as regulation, since industry and policy makers often ignore the externalities of their decisions on how much land they want to convert in a given year.

In conclusion, Lee said there is a huge opportunity for both research and policy developments using a One Health approach to managing multiple global issues simultaneously. She called for better understanding of the total economic costs, both direct and indirect, of emerging infectious disease events to inform policy options. The health costs associated with lost ecosystems, she added, can be used to build discussion and change incentives for the implementation of a One Health approach.

DISCUSSION

As moderator, Cameron posed the first question to the panelists, asking them to identify an area that they would like policy makers to prioritize for strengthening national preparedness for microbial threats.

- Nyenswah stated that he would push for a One Health approach to preparedness, linking animal health and human health surveillance and response efforts. He noted that he has witnessed the benefits of this strategy in the context of rabies, Lassa fever, yellow fever, malaria, and Ebola control in Liberia.

- Gilsdorf called for increased multisectoral collaboration with a clear understanding of each sector’s needs and agreement on a way to work together. In addition, he emphasized the importance of investing in training the public health workforce responsible for outbreak preparedness and response.

- Berthe agreed that investing in implementing a One Health approach is critical, focusing on educating the new generation of public health workers to prevent them from working in siloes.

- Lee noted that investment in prevention is a difficult sell to policy makers. Therefore, she proposed highlighting the direct and indirect costs of existing health threats, including livestock diseases and vector-borne illnesses. She shared the example of malaria, which has numerous indirect costs including its effect on tourism and lost productivity. She argued that showing the actual costs of such threats to policy makers would make a stronger investment case for prevention as well as introducing the cobenefits of the One Health approach to manage them.

Cameron opened up the discussion to the audience, which first focused on specific issues related to the development and implementation of preparedness efforts. Jay Siegel, former chief biotechnology officer of Johnson & Johnson, asked about the current research efforts in the field of behavioral economics and communications to support the design and implementation of interventions for outbreak preparedness and response. Lee stated that there is much to learn from studies that evaluate public thinking and the adoption of new practices around topics such as climate change. She highlighted the need to understand how people discount future values to consider present benefits or costs. Berthe agreed that when it comes to behavior, providing facts is not enough. He cited AMR as an example where knowledge has not been sufficient to address this threat. Therefore, he highlighted the need for investing in health systems that can respond when an unexpected outbreak occurs. Gilsdorf noted that it is critical to invest in communication research to achieve behavioral change and consider the way information is transmitted and has evolved through new media and new styles of journalism and political activity.

Thomas Inglesby, director of the Center for Health Security of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, asked the panelists for examples of a strong national One Health intervention and its key

features. Berthe responded by listing champions of One Health including Bangladesh, Botswana, Liberia, Senegal, and Vietnam. He added that the global response to H5N1 influenza has raised the profile of the One Health approach, but that there is a need for better indicators to consistently measure the success in implementing this approach.

Kimberly Thompson, president of Kid Risk, Inc., noted the challenge of accounting for the full effect of preparedness efforts that are put in place and wondered about the possibility of leveraging existing health networks and initiatives to help support these efforts that can lead to systemwide impact. Thompson asked how these challenges are taken into account when modeling the cost of preparedness efforts. Berthe responded by stating that there is a need to invest in systems. He noted that veterinary services and food safety are examples of systems that should be in place for routine services and can be ready in case they are needed to respond to an outbreak. Gilsdorf argued that preparedness should not focus on one or two diseases, but instead be generic enough to be able to counter a variety of threats. Measuring the success of this approach, however, is more difficult compared to disease-specific programs, he said. Nyenswah stated that preparedness programs should be holistic, and involve emergency operation centers, training, capacity building, and simulation exercises. While Cameron recognized the importance of investing in strengthening health systems, she highlighted the challenges of raising funds for this purpose and noted that these efforts may need to be linked to specific diseases to be successful. This allows policy makers to understand and demonstrate the linkages between investments and outcomes, she said.

Patrick Hickey, chair of the Department of Pediatrics at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, asked how the economics community can help policy makers to design interventions with enough specificity to ensure impact, but also enough flexibility to respond to evolving needs. To illustrate his question, Hickey shared his experience in the West Africa Ebola response, where funding was available for building treatments units that were no longer needed but could not be used to address other critical needs. Nyenswah agreed that funding should be flexible enough to respond to changing circumstances. He argued that policy makers should build flexibility into funding programs so the institutions implementing them can respond to evolving situations. He reiterated that in Liberia, it was difficult to move the funding assigned to building temporary Ebola treatment units to focus on health systems strengthening. Gilsdorf agreed that flexible funding is a challenge, and shared his experience interacting with health ministers who said that the issue stems from the realities of zero budgeting for national programs. On interaction with policy makers, Gilsdorf noted that effective communication is essential, which sometimes means simplifying information rather than providing more details.

Martin Meltzer, senior economist and distinguished consultant at CDC, asked the panelists how to measure and best demonstrate the effect of improved surveillance and response when the public health community mainly relies on measuring the effect of an intervention with the number of deaths and cases averted. Nyenswah responded that the number of deaths averted can be a good indicator of the effect of a robust surveillance system. He cited as an example that the improvements made in the health system in Liberia (including a stronger surveillance system) prevented many deaths during several Ebola flare-ups, a meningitis outbreak, and a measles outbreak.

The discussion ended on the topic of building the investment case and persuading policy makers about preparedness. Peter Sands, executive director of The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, commented that it is difficult to convince governments to make investments toward threats in the future when they face high burdens of diseases in the present. He highlighted the need for a broader definition of health security that starts with the diseases that currently pose the highest risk and build capacities and infrastructure to address those, which would also prepare the world to better respond to future threats. Lee responded by emphasizing the potential for the One Health approach to address preparedness from the perspective of both current endemic and emerging infectious diseases. She shared the example of malaria, where the One Health approach raises issues related to environmental interactions and the breeding grounds for mosquitoes. Nyenswah stated that the resources in low- and middle-income countries are directed according to local burdens of disease. However, he noted, there is an opportunity for a greater impact if the investments coming from development partners are used to implement a more holistic approach after agreeing on shared priorities. He recommended that initiatives focusing on countering infectious diseases prioritize making systemwide impacts instead of creating vertical programs.

Finally, Keiji Fukuda, clinical professor and director of The University of Hong Kong School of Public Health, observed that the health sector has failed to convince policy makers of the need to consider health and preparedness as good investments, rather than see them as expenditures needed to respond to emergencies. He noted that the uncertainty around the inclusion of health as a Sustainable Development Goal demonstrated this challenge and asked panelists to comment on how to shift this paradigm on health investments. Gilsdorf responded by calling for more efforts focused on recognizing infectious diseases as economic and security threats, which in the past couple of years the public health community has been somewhat successful. He noted that building strong health systems should be an issue of high societal concern, but noted that this is difficult given the short-term vision of decision makers.

Cameron concluded the discussion by agreeing with the need to make better arguments on the importance of investments in the health sector. She noted that health broadly, and not only pandemic preparedness, should be considered a security-related investment, and funders and governments should come together to discuss and agree on the right messaging to advocate for this investment.