8

Reimagining Sustainable Investments to Counter Microbial Threats

Session III, part A, examined ways to invest in sustainable solutions to combat microbial threats globally and in resource-limited settings. The session was moderated by Peter Sands, executive director of The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. The session featured two presentations: Dean Jamison, professor emeritus in global health at the University of California, San Francisco, presented on the economics of international collective action to control microbial threats, focusing on the landscape of development assistance for country-specific and global health functions. Tania Zulu Holt, partner at McKinsey and Co., discussed economic bottlenecks in delivering medical products across Africa and the role of human-centered costing to ensure supply chain sustainability in resource-limited settings.

ECONOMICS OF INTERNATIONAL COLLECTIVE ACTION TO COUNTER MICROBIAL THREATS

Dean Jamison, professor emeritus in global health at the University of California, San Francisco, began by describing two realms of decision making brought about by international aid that aims to counter microbial threats: country-specific decisions by national governments and international collective action by global institutions. The two are interrelated and often part of a two-stage decision process, since national governments respond with resource allocation decisions based on aid disbursement and policy decisions of international agencies. Jamison described the potential issues of the two-step process of aid flow and recalled Lawrence H.

Summers’s remarks on fungibility of aid (see Chapter 2). For example, once a donor allocates $10 million designated for tuberculosis (TB) control to a country, the country’s government then responds by using donor funds on TB control but potentially reallocating its domestic TB budget elsewhere in the health sector or outside of health altogether.

Decision Making About International Aid for Health at the Country Level

As for decision-making dynamics within a national government, Jamison described how health investment decisions are made. He specified that ministries of finance are often the ones responsible for allocating funds. When making such decisions, he said, ministries of finance are concerned with identifying the resource needs, weighing the specific value of different kinds of investments in activities such as pandemic preparedness to their country, and determining what fraction of the value of that investment will fall outside of the country. He argued that ministries of finance tend to be primarily concerned with maximizing the fraction of funds that will remain in the country.

Jamison mentioned four broad motivations of international aid agencies to influence decision making in recipient countries. First, he noted the aid agencies may be motivated to ease resource constraints. For the poorest countries, he said easing resource constraints is the primary goal of aid, but for middle-income countries where the goals shift, the issue of fungibility surfaces more prominently. Second, Jamison said aid flow has effects on national prices and incentives faced by governments when making budgetary allocation decisions, noting that incentives may change the ease of conducting certain activities because of the addition of donor funds. He added that the third motivation may be to change the information environment. When aid is done well, he clarified, a substantial amount of technical information and knowledge learned in one country or from a scientific community is transferred to another country. Finally, he noted that the international system adopts shared risks facing individual countries when donor agencies provide aid.

Country-Specific Versus Global Functions in International Aid for Health

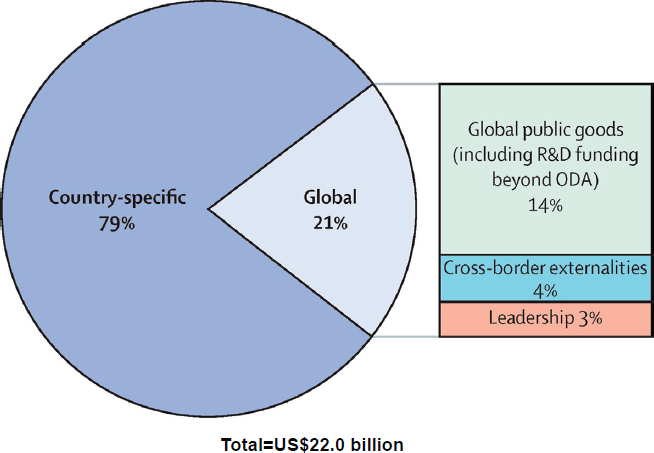

Jamison explained that there are functions of international aid for infectious disease management that can be divided into two categories. One is country-specific functions that strengthen national disease control and health systems, and the other category is global functions that aim to meet global goals, such as those supporting core global public goods (e.g., research and development [R&D]), managing cross-border threats (e.g., outbreak and antimicrobial resistance response), and fostering leadership

and stewardship. Currently, country-specific investments are the predominant way development aid for health is used (see Figure 8-1). He specified that the focus of investments for country-specific or global functions are different in low- and middle-income countries versus high-income countries. For example, the majority of donor funds for country-specific functions in low- and middle-income countries are focused on financing health services delivery, whereas in high-income countries they are focused on training health workers from low- and middle-income countries. He added that investments for global functions in low- and middle-income countries assist with national efforts in transnational activities, such as pandemic preparedness. In high-income countries these investments also target management of cross-border externalities, as well as global public goods, leadership, and stewardship initiatives.

Jamison pointed to some of the problems of investments for country-specific functions. He reiterated the disposition of some finance ministers, who would be reluctant to invest in domestic preparedness activities if

NOTE: ODA = official development assistance; R&D = research and development.

SOURCES: Jamison presentation, June 13, 2018; Schäferhoff et al., 2015. Reprinted from The Lancet, Vol. 386, Schäferhoff, M., S. Fewer, J. Kraus, E. Richter, L. H. Summers, J. Sundewall, G. Yamey, and D. T. Jamison, “How much donor financing for health is channelled to global versus country-specific aid functions?”, Pages 2436–2441, Copyright (2015), with permission from Elsevier.

the value of the investment is seen as more beneficial on the transnational level and particularly if external aid will make up the difference. Jamison also highlighted the spectrum of aid fungibility among the country-specific functions, where pandemic preparedness is less fungible than health system strengthening and disease control investments. On the other hand, he said aid for global functions toward R&D of health tools and managing cross-border externalities are considered nonfungible.

To conclude, Jamison drew attention to two main gaps in the $22 billion in overall annual health aid across country-specific and global functions. First, he said existing international systems are likely preventing donor funds from effectively benefiting the poor in middle-income countries; the more fungible the aid funding, the less likely it is to reach the poor. Thus, funding more R&D and other global functions as opposed to country-specific functions may be a better strategy to ensure that donor support reaches poor individuals in middle-income countries more directly (Schäferhoff et al., 2015). In addition, Jamison prioritized several key global functions that continue to be underfunded, including development of better drugs and vaccines for TB and influenza pandemic preparedness. Shifting aid away from country-specific purposes toward these global function priorities is what Jamison believes economic analyses is increasingly pointing toward as a desirable path.

OVERCOMING ECONOMIC BOTTLENECKS IN DELIVERING MEDICAL PRODUCTS TO ADDRESS MICROBIAL THREATS ACROSS AFRICA

Tania Zulu Holt, a partner at McKinsey and Co., presented on the realities she has observed on the ground of supply chain bottlenecks in delivering medical products across Africa. She began with a vignette of a nurse named Amina in Nigeria and her struggle to provide vaccination, reproductive health care, and other services at clinics because of inconsistent access to medical products (see Box 8-1). Holt noted that this portrayal is not representative of the country or continent but provides context for the complicated layers of supply chains that can run through one facility, which is magnified to thousands of facilities nationally and relies on dozens of data systems tailored to different donors.

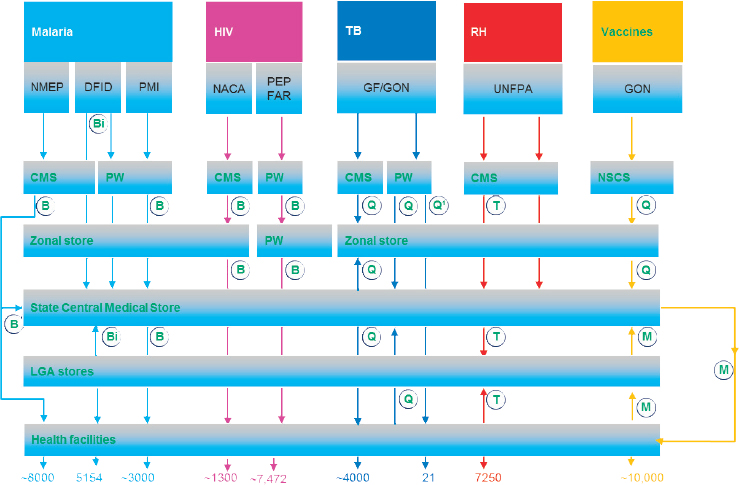

Holt described how medical products are often delivered through vertical, disease-specific supply chains that operate through different mechanisms, funding streams, and resources (see Figure 8-2). She noted that different commodities can be delivered twice per year, three times per year, quarterly, bi-monthly, or monthly. While some products pass through state and local government warehouses, others bypass these levels and are delivered directly to clinics. According to Holt, this leads to multiple inefficien-

cies and economic bottlenecks that lead to significant costs and barriers to effective service delivery. Frontline health workers, like Amina, are expected to manage these overlapping systems by devising their own unique coping strategies in order to deliver health services.

Human-Centered Approach in Costing Medical Product Supply Chains

Holt described the high costs typically accounted for in systematic planning of medical product delivery to health facilities, including the costs associated with procurement, warehousing, and delivery. She argued that

NOTES: Medical products for malaria, HIV, tuberculosis (TB), reproductive health (RH), and vaccination are delivered through various pathways through the Nigerian health system.

B = bi-monthly; Bi = twice per year; CMS = Central Medical Store; DFID = U.K. Department for International Development; GF = The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; GON = Government of Nigeria; LGA = local government area; M = monthly; NACA = National Agency for the Control of AIDS; NMEP = National Malaria Eradication Program; NSCS = National Strategic Cold Store; PEPFAR = The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief; PMI = President’s Malaria Initiative; PW = private warehouse; Q = quarterly; T = three times per year; UNFPA = United Nations Population Fund.

SOURCE: Holt presentation, June 13, 2018.

this approach ignores the last mile costs, which are often out-of-pocket payments made by nurses, doctors, and health extension workers who travel to higher-level facilities to pick up supplies. Additionally, the opportunity cost for patient care is unaccounted when skilled health care workers are traveling to get medical supplies when they could be seeing patients. Another cost occurs when patients visit a clinic for health services and are turned away because of stock outs. These patients also spend money to travel to these facilities in addition to time and wages that they forgo by

missing work. Holt stated that in higher levels of government, supply chain managers and program officers often use their own resources to sponsor operational funds or to coordinate logistics since government funding is not necessarily released to align with supply chains. According to Holt, these “human-centered costs” are not adequately accounted for in supply chain evaluations and require looking beyond on-the-surface warehousing and fuel costs. She argued that this oversight leads to underperforming systems, supply shortages, and other inefficiencies.

Potential Strategies for Reducing Economic Bottlenecks

Holt described four strategies to reduce economic bottlenecks in the medical product supply chain, despite the challenge in distilling the exact costs of integrating supply chains and investing in other potential solutions. Firstly, zero-based budgeting, where all economic costs are reevaluated bottom up and justified for each new time period, can help to better account for human-centered costs and provide a more accurate baseline in countries and remove hidden costs. Second, she noted that there are many inefficiencies associated with multiple vertical supply chains for warehousing and last mile delivery, and that these should be better integrated to reduce costs. Outsourcing of supply chain operations to the private sector is another strategy that can also increase efficiency, reducing costs by 5 to 15 percent, Holt said. She acknowledged that outsourcing is not an easy option for governments to consider, but it can overcome many last mile economic bottlenecks by distributing commodities directly to facilities. The fourth strategy she highlighted is investing in better, single platform data systems to reduce waste and improve quantification at the facility and central levels.

Holt provided an example of cost savings on integrating last mile delivery of health commodities for potentially addressing these bottlenecks. From a McKinsey analysis of overlap in last mile delivery across 1,121 primary health facilities and 5 donor programs in a Nigerian state, Holt noted that only 12 percent of facilities were delivering the full complement of services being evaluated. However, the calculated annual savings could potentially reach $10.6 million if full last-mile integration of health commodity supply chains across the various service delivery programs were applied to the entire country (see Box 8-2).

Holt concluded by highlighting the need to invest in country-level supply chain systems that can be leveraged for both routine services and for future emergencies. While international donors are spending billions of dollars on health commodities in Africa, she noted that there is not nearly enough spending on product delivery. Conversely, the pharmaceutical industry spends between 4 and 11 percent of their commodity value on supply chain, she said. Holt argued that if between 2 and 3 percent of

health commodity value in Africa was directed toward this goal, it would equate to nearly $1 billion available to strengthen supply chains and inter-agency collaboration.

DISCUSSION

The discussion began with two questions on health systems strengthening, focusing on country ownership and cost-effectiveness of health interventions. Kimberly Thompson, president of Kid Risk, Inc., asked about the difficulties of tracking fungible health systems investments and the need for more transparency to understand the full costs embedded in systems, in order to build local capacity. She inquired about holding countries accountable for service delivery performance across disparate national health systems. Jamison responded that despite the traction behind health systems strengthening, aid is still predominantly spent on disease-focused programs since broader systems-focused programs are more difficult for donors to evaluate and attribute health outcomes to their funds. In his opinion, country-specific efforts that are tightly focused on health objectives such as mortality reduction, will preserve accountability and avoid the fungibility issue.

Katharina Hauck, senior lecturer at the Imperial College London, observed the scope of the McKinsey analysis of primary health facilities in Nigeria and asked about the methodological challenges of evaluating the cost-effectiveness of health systems strengthening initiatives, particularly

with the economies of scope for clinics delivering multiple services. Holt highlighted the need for more cost-effectiveness analyses at the country level despite the challenges, in order to evaluate current inputs into health systems, performance level, and benefits from investments in one area over the other. Without understanding the trade-offs, she said it would be difficult for payers within the system to direct program design and make future investments. On the issue of aid accountability, Holt commented that some countries are too fragile to consider health systems strengthening initiatives, while others are economically developed enough to aim for service delivery beyond traditionally donor-funded diseases. In this second category of countries, there is an opportunity to engage and support them in transitioning from vertical programs to a systems approach though there will be challenges with accountability, she said.

The discussion transitioned to specific questions about Jamison’s presentation. Jonna Mazet, executive director of the One Health Institute at the University of California, Davis, asked about the relative benefits of country-specific versus international collective action approaches and wondered about the potential for hybrid programs. For example, U.S. Agency for International Development programs invest in both global functions, such as R&D, with country-specific aims to build local capacity for national pandemic preparedness. Jamison responded that the hybrid program she described was the political “sweet spot” of funds advancing a global public good while actually being spent within countries. He noted that spending to advance international collective action such as pandemic preparedness can be done at any level—within low- or middle-income countries, high-income countries, or in agencies.

Finally, Mukesh Chawla, advisor for health, nutrition, and population at the World Bank, asked Jamison how to better bridge the political and economic incentives behind investments for global public goods in conversations among countries, donors, and the international community. Jamison noted that a major motivation yet challenge of aid is translating international experiences to local contexts. Jamison stated that both politics and economics are important considerations, but that the international community “often has little to say about domestic politics and a great deal to say about economics. I think we, on the outside, should probably focus on the economics.” Similarly, he said while health systems are unquestionably important, they are domestic issues, about which the international community does not always have robust knowledge and understanding. Rather, the international community has the technocratic capacity for disease control such as for HIV and TB, and some supply chain management issues that could bring value to countries, he said. Jamison argued for the international community to focus on areas where it has clear capacity and knowledge to bring value to countries.

This page intentionally left blank.