3

Creating a Pipeline of Financing for Population Health: Exploring Sin Taxes and Tax Credits

What is classified as health care is expanding, said Kathy Gerwig, vice president for Employee Safety Health and Wellness at Kaiser Permanente, and session moderator. Health issues do not stay within the walls of an exam room or a health care facility, and addressing the social, economic, and environmental determinants of health includes helping people access affordable housing, reliable transportation, and employment. Lowering the barriers to what creates an environment for health includes addressing tax policy issues. Conversations about climate change, for example, include discussions of the carbon tax. As discussed, a goal of the workshop is to provide participants with the information and tools to join in those conversations about the tax aspects of health issues and contribute in a thoughtful and meaningful way. In this session, two panels discussed different tax policy approaches for generating funding to support population health, including selective excise taxes or “sin taxes,” and tax credits.

Aysha Pamukcu, senior staff attorney at ChangeLab Solutions, discussed how sin taxes can be used as a public health tool, and what some of the unintended consequences can be.1 Xavier Morales, executive director of The Praxis Project, described his experience with the passage and implementation of the Berkeley sugar-sweetened beverage tax as an example of how leading with health justice and engaging the community

___________________

1 Pamukcu referred participants to the ChangeLab Solutions website for a variety of law and policy tools for community health. See https://www.changelabsolutions.org/tools-change (accessed February 2, 2018).

contributes to the success of proposed tax measures. Meredith Fowlie, an associate professor, and Jim Salle, an assistant professor, both in the Department of Agriculture and Resource Economics at UC Berkeley, discussed the connections between cap-and-trade pollution regulation and community and local health issues.

In the second panel, Stacy Becker, vice president of programs at ReThink Health, discussed the potential of tax credits to improve population health. In preparation for the breakout activity (see Chapter 4), Becker presented a fictional case scenario set in the state of “Ourlandia.” Nina Burke, program associate at ReThink Health, and Amanda McIntosh, program and communications associate at ReThink Health, then presented two prototype population health tax credit proposals for consideration. The panel was moderated by Anne De Biasi, director of policy development at Trust for America’s Health (TFAH). (Highlights are presented in Box 3-1.)

SIN TAXES2

Selective Excise Taxes as a Public Health Tool

Sin taxes, began Pamukcu, are selective excise taxes designed to affect consumer behavior. These targeted consumption taxes are placed on retail items such as tobacco, alcohol, and gasoline, Pamukcu said. “Sin” implies that the commodities that are the subject of this tax are somehow immoral, undesirable, or harmful to the individual or the community. While that may be the case, Pamukcu called for reimaging the sin tax as something that is less stigmatizing and more affirming for positive social good. She noted the discussion by Johnson and Brown (see Chapter 2) about the need to be more explicit about the connection between public health and tax policy. While taxes have a primary and well-understood purpose of raising money for the government, they are also a good tool to nudge consumer behavior and drive change in collective norms. In addition, these taxes provide important funding for preventative public health efforts, helping to counteract the high societal costs of certain commodities (e.g., sugary drinks as a food item are relatively inexpensive to produce and purchase; however, the costs to society through increased health care costs can be high).

Pamukcu highlighted several ways in which taxes can be used as a public health tool. First, taxation can be leveraged to address health

___________________

2 This section is the rapporteur’s synopsis of the presentation made by Aysha Pamukcu of ChangeLab Solutions, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

disparities. The burden of chronic disease caused by unhealthy retail commodities falls most heavily on underserved communities, she said. She observed that liquor stores and fast food restaurants are generally clustered in neighborhoods that also have the most advertising for these commodities and that bear the highest cost of the negative externalities of these commodities. Second, taxation can build on existing public health strategies. Taxes should be thought of as one tool among many for promoting public health, she said. For example, taxes on alcohol are a tool to reduce the negative externalities caused by binge drinking, and they

can be coupled with complementary tools that have strong evidence base, such as restricting the density of shops that can sell alcohol, maintaining limits on the days of sale, and enforcing laws that restrict sales to those who are underage. When all of the tools in the toolbox are deployed, then the negative effects of binge drinking can be combatted. Finally, taxes can produce funding for community health priorities.3 Taxes can be earmarked for specific purposes, and Pamukcu emphasized the importance of consulting with the communities that are most affected by these unhealthy commodities and ensuring they have a voice at the policy-making table. Pamukcu listed some specific examples of taxes that can be used as a public health tool, including taxes on:

- substances, such as tobacco, alcohol, cannabis;

- nutrition, such as sugary drinks, junk food, specific ingredients (e.g., high fructose corn syrup); and

- goods and activities, such as gasoline, gambling, and activities that create pollution.

Behavioral, Health Outcomes of Excise Taxes on Consumable Goods

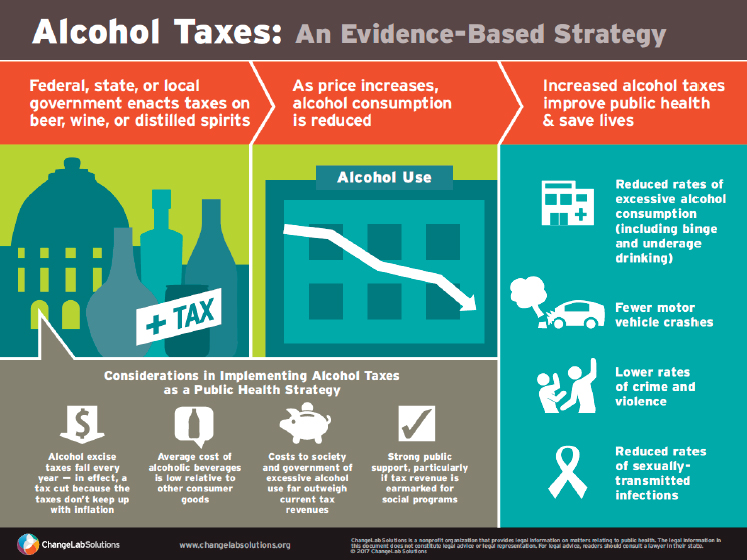

Pamukcu shared an infographic developed by ChangeLab Solutions that visualizes the relationship between taxes and public health (see Figure 3-1). The graphic illustrates the flow from alcohol tax laws, to an increase in price in the commodity, to a corresponding reduced consumption, and finally, to improved public health outcomes.

Another example is the effect of cigarette taxes on smoking in the United States. Smoking rates increased steadily from the early 1900s through the 1960s, in part, as an unintended consequence of a public policy that provided cigarettes to troops abroad during World War II (intended as a comforting gesture). These addicted troops returned home and influenced the smoking behaviors of their families, driving cigarette use higher, Pamukcu explained. Following the first Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking in 1964, and subsequent education campaigns, the rates of smoking began to level off and then decline. It was not until public policy interventions, including the nonsmokers rights movement and the doubling of the federal cigarette tax, however, that the rates of smoking declined significantly. It was these public policies that drove the decline of tobacco use, she said. In California, a comprehensive mes-

___________________

3 Although in this workshop, community health is used in reference to the health status of a geographic community (county, city, etc.), and as part of terms such as community health needs assessment or community health improvement plan, the term community health is fairly ambiguous. For a more in-depth discussion of its definitions and usage, see Goodman et al., 2014.

SOURCES: Pamukcu presentation, December 7, 2017, published by ChangeLab Solutions, https://www.changelabsolutions.org/publications/alcohol-taxes-infographic (accessed February 2, 2018).

saging and public policy campaign produced huge savings for the state. From 1989 through 2008, 6.8 billion fewer packs of cigarettes were sold, there were 25 percent fewer tobacco-related diseases (compared to the rest of the nation), and the state saved $134 billion in personal health care expenditures.

From an equity and fairness perspective, it is important to note that there are complex considerations to contend with when implementing excise taxes on consumable goods. Using tobacco as an example, Pamukcu said that, even though rates of tobacco use have been declining across the United States, not all populations experience that decline, and the corresponding health benefits, in the same way. Smoking rates are disproportionately high among racial and ethnic minority individuals (especially Native American individuals). Younger people are more likely to smoke than older people, and rates of smoking remain disproportionately high among those living in rural communities, or with limited education. The public health field and the tobacco control field will have to evolve accordingly, Pamukcu said, to craft more nuanced and equitable

solutions that are tailored to the needs of populations who are left behind by recent policy successes.

Tax Tools in Practice

The federal and state governments employ taxes on specific commodities as a public health tool, and increasingly, more local governments are starting to leverage this approach. For example, in the San Francisco Bay Area of California, there has been movement on taxing sugar-sweetened beverages (discussed further by Morales). The challenge for local governments, however, is that their ability to tax is restricted by preemption. Preemption means that the law of a higher jurisdiction invalidates the law of a lower jurisdiction, Pamukcu explained. In the case of alcohol taxes for example, a local government’s ability to tax varies by state. Only 19 states allow local governments to tax alcohol. Among those 19 states, there are various restrictions on how local governments can tax. For example, the type of commodity might be restricted, such that taxing beer is allowed but taxing wine is not. There might be a restriction on the amount of tax or a restriction on how the funds can be earmarked. Ultimately, a local government’s ability to innovate on taxes varies by state and by commodity, she said.

It is important to question who is benefiting from a given tax policy and how, Pamukcu said, and she highlighted the need to keep health equity in mind. One of the first principles of health equity and selective excise taxes is community partnership and education. It is important to recognize and respect that the people who live in the community are the experts on themselves, their lives, and their neighborhoods, she said, and they need to have a voice in tax policy making. The next equity principle is creating a positive ecosystem of health. This involves both decreasing negative, unhealthy influences in a community, and increasing positive healthful influences. Another equity principle in the framing of taxes is earmarking and the equitable use of tax revenues. Tax dollars should be directed toward supporting the people who bear the highest burden of chronic disease and unhealthy commodities, and to the priorities they articulate for their communities. Lastly, tax policy should not stigmatize individuals or groups, Pamukcu said. She noted that tax policies that affect individuals, such as a consumer tax on the price of cigarettes, can create a false sense that wellness is directly the result of individual choices. Obviously, there are broader systemic forces that determine personal and community wellness, and it is important not to lose sight of that when considering consumer-based taxes.

Putting tax tools into practice can also have unintended consequences, and Pamukcu reminded participants to “check for blind spots” when

using selective excise taxes. She shared several examples of unintended consequences and blind spots to look for. First and foremost, excise taxes are regressive. These taxes take a greater percentage of the income of low-income individuals. However, Pamukcu noted, it is necessary to consider the regressivity of excise taxes in the broader context of chronic disease, poverty, and other social determinants of health that are themselves extremely regressive by nature. Another consideration when implementing an excise tax is that the government might be dependent on the commodity for revenue. In taxing tobacco, for example, governments might find that they are dependent on the tobacco products themselves to raise funds. Undesirable consumer adaptation is another potential unintended consequence. For example, people could adapt by switching geographies (e.g., buying their cigarettes in the neighboring county) or by switching products (e.g., switching to beer, which is taxed at a lower rate than liquor). Another aspect to be mindful of, she said, is not pairing taxes with additional public health strategies. Taxes, Pamukcu stated, are one tool in a broader toolbox, and it is important to think about these strategies holistically and collectively.

Looking Ahead

The future of excise taxes (i.e., sin taxes) as a public health strategy is a question for the broader public health community, Pamukcu concluded. Deploying them as a tool will require creative thinking to answer some difficult questions. How can excise taxes be combined with other evidence-based strategies? How can it be ensured that those who are most disadvantaged will benefit from taxes and other public health strategies? To start, she reiterated the suggestion to rebrand these taxes so they are less about reducing “sin” and more about advancing health, and making them a standard part of the public health toolkit.

Leading with Health Justice: Berkeley Versus Big Soda

Building on the background provided by Pamukcu, Morales shared some of the lessons learned as Berkeley, California, worked to pass and implement the nation’s first sugar-sweetened beverage tax.4 Having studied similar attempts across the country, Morales observed that what differentiates Berkeley versus Big Soda from other efforts is that Berkeley

___________________

4 This section is the rapporteur’s synopsis of the presentation made by Xavier Morales of The Praxis Project, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Morales gave his presentation via web conference.

led with health justice as the focus. Health justice, Morales explained, is the next step beyond health equity. If, for example, equality means everyone has the same pair of shoes, and health equity means that all the shoes fit, then health justice means that the shoes help the person wearing them to navigate their environment and are suited to their personality and identity. He concurred with previous speakers about the importance of ensuring that those who are most affected are represented at the table for the policy discussions. Following the success by Berkeley, similar soda taxes have been passed in Oakland, San Francisco, and Albany, California, as well as Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Seattle, Washington. A soda tax was also passed in Cook County, Illinois, but was recently repealed, and Morales suggested that the campaign did not engage communities to the level where they would be defenders of the policy.

The Berkeley Strategy

The soda tax was passed by Berkeley voters in November 2014. Meetings and negotiations among the coalition leadership team began 1 year and 3 months beforehand. Morales said that the City of Berkeley was able to engage communities in the campaign by quantitatively demonstrating existing health disparities. The 2013 Health Status Report from the city found that 40 percent of ninth graders in Berkeley’s public schools were overweight or obese, with students of color much more likely to be overweight or obese than white students. Morales explained that a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture for nutrition education programs was expiring, and the school district needed to replace it with sustainable funding. The initial thought was to institute a soda tax and use those funds to support nutrition education programs in the Berkeley Unified School District. While that was a good idea, there was a clear need to directly address the health and nutrition needs of the communities that were most affected by the overconsumption of sugary drinks through the provision of community-based programming and services.

The coalition strategy team agreed that community-based healthy food access and early childhood nutrition programs also needed sustainable funding. Health justice concerns were raised that simply funding cooking and gardening programs in the schools would add to gentrification pressures and would reinforce the educational disparities that already existed in Berkeley between students of color and white students. It was also acknowledged that, if rates of disease in African American and Latino children were held up as the reasons why the tax was needed, then it was essential to show that the revenues were actually going back into those communities. The intent of the campaign was to increase community capacity to deliver services and build community resilience, not just

to reduce consumption of sugary drinks by raising the price so price-sensitive populations could not afford to purchase these products, Morales said.

Morales highlighted several of the challenges to pulling together the coalition and keeping true to the campaign’s intentions. Internally, there were those who prioritized funding school-based cooking and gardening programs. There were also those who prioritized investing in the communities most affected by chronic diseases that result from the overconsumption of sugary drinks. It was important to make sure that both of those perspectives were considered. Externally, there were those who truly believed that all that was needed to curb consumption of sugary drinks was to raise the price of sugar-sweetened beverages, and price-sensitive residents would then choose healthier alternatives. Also, there was a small but very vocal group of supporters that had strong anticorporate views who just wanted to “beat Big Soda.”

Having these diverse interests and diverse leadership at the table helped to successfully shape an accepted tax campaign strategy. Morales described the previous strategy that had failed 30 times across the country as “public health perfect/political bad.” The previous strategy called for raising the soda price 2 cents per ounce, as a dedicated tax (versus a general fund tax)5 and a retail tax (so consumers would feel the effect at the cash register). The major focus was on raising prices to curb demand and consumption for price-sensitive populations. Success of the tax was defined by an increase in the price of the soda, which theoretically would lead to decreased consumption.

The Berkeley strategy was based on knowing the community and understanding what was needed to win. In contrast to the previous strategy, the Berkeley strategy was “political perfect/public health good,” Morales said. The strategy included a 1 cent per ounce tax, which went into the general fund, and a panel of experts would advise the Berkeley City Council on how to invest these funds.6 The tax would be an excise tax, paid at the distributor level. The focus was on generating revenue to address the complex roots of diseases caused by the overconsumption of sugar water. Success was defined by achieving increased community knowledge, and behavior changes by those receiving the benefits of the investment.

___________________

5 California tax law requires a 66 percent majority to pass “specific” or “dedicated” taxes compared to 50 percent +1 majority to pass tax measures going into the general fund.

6 Because this is a general tax that goes into the city’s general fund, the panel of experts was added as part of the measure to give confidence that the city would approve the expenditure of general funds to improve health. Each member of the panel of experts is appointed for a specified term by each of the city council members.

The Berkeley strategy identified priority populations to help ensure that funds were targeted to the communities where they were needed most. Priority populations included children and their families, with a particular emphasis on young children who are in the process of forming lifelong habits; individuals with limited resources; groups exhibiting higher than average population levels of diabetes, obesity, and tooth decay rates; and groups that are disproportionately targeted by beverage industry marketing.

Revenues and Investments

After the first taxable year (March 2015 through February 2016), $1.4 million in revenue was contributed to the general fund from the sugar-sweetened beverage tax.7 The total revenue through July 2016 was $2.085 million. The average monthly revenue for 2015 was about $118,000, and for 2016, $128,000. Morales noted that Berkeley has about 100,000 people, and the rule of thumb is that, for every 100,000 people in the community, $1.5 million in revenue can be expected. As per the strategy, the tax is paid by the distributors, and all 44 distributors to the city were filing these taxes. In 2016, small retailers were added, increasing the number of tax filers to 144.

After the first year, the leadership group made recommendations for investments, which were approved by the city council. About 42 percent of the revenues ($637,400) were used to support school-based nutrition education and cooking classes through the Berkeley Unified School District. Another 42 percent ($637,400) went to support community-based efforts to increase awareness and change norms and practices. A significant portion of these funds went to four key community programs that had submitted proposals for consideration by the panel of experts who in turn made funding recommendations to the Berkeley City Council: Healthy Black Families, the Ecology Center, the YMCA, and Berkeley Youth Alternatives.

Because it is difficult for small community groups to staff up and operate on a 1-year grant, for the 2nd-year recommendations the leadership group asked for and received from the Berkeley City Council $3 million over 2 years to support 2-year grants. Again, about 42 percent went to the Berkeley Unified School District, another 42 percent was awarded to community programs. The Berkeley Public Health Division received 15 percent for administration and to support evaluations.

___________________

7 Again, because Measure D was a “general tax,” there is not a dollar-for-dollar equivalency between the soda tax revenues going into the City of Berkeley’s general fund and the panel of experts’ investment recommendations.

Evaluations

Morales briefly reviewed the evaluations to date. Cawley and Frisvold estimated an average pass-through rate of 43.1 percent across all beverage brands and sizes studied (Cawley and Frisvold, 2017). In other words, for every penny that was raised by the tax, 43.1 percent was passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices. Stores in Berkeley located further from the border of neighboring cities shifted more of the tax on the consumers, compared to those closer to the border of the city. Morales noted that, as neighboring Oakland and Albany have also passed a soda tax, it will be interesting to see what the subsequent data show.

An early evaluation by Falbe and colleagues, 3 months after the tax was implemented, found that the price of soda in Berkeley increased by 0.69 cents per ounce for single-sized servings (Falbe et al., 2015). Overall retail prices for sugar-sweetened beverages increased more in Berkeley than the comparison cities. Pass-through was highest for soda compared to other sugar-sweetened beverages, and across retailer types, drugstores had the lowest pass-through rates (possibly because pricing by stores such as Walgreens and CVS is regional).

In 2016, Falbe and colleagues found that the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages decreased by 21 percent in Berkeley, and increased by 4 percent in comparison cities (Falbe et al., 2016). Water consumption increased more than 63 percent, and only 2 percent of people who purchased sugar-sweetened beverages at Berkeley before the tax reported buying them in another city after the tax. Twenty-two percent of participants reported changing drinking habits as a result of the tax.

Silver and colleagues found that, across all sugar-sweetened beverages, 67 percent of the tax was passed through, but that it was more fully passed through (prices rose more than 1 cent per ounce) for both sodas and energy drinks after 1 year of the tax (Silver et al., 2017). Among 26 retailers studied in Berkeley, the tax was fully passed on in large and small chains and gas stations, but partially passed on in pharmacies. Sales in ounces of taxed sugar-sweetened beverages decreased in comparison to predicted sales, and sales of untaxed beverages, especially water, increased. There were no significant changes in overall beverage consumption, noting that Berkeley residents consumed lower quantities of sugar-sweetened beverages at baseline compared to the national average, Morales said. There was also no evidence of higher grocery bills, lower revenue for stores, or overall decreases in beverage sales for retailers.

Finally, a study focused on the UC Berkeley campus found that sales of soda declined by 30 percent (relative to other beverages) immediately after the passage of the tax, but before implementation (Taylor et al., 2016). Sales remained depressed after the tax was implemented on campus. It

is noteworthy that campus retailers did not pass on the tax to consumers until more than 1 year after implementation. Thus, Morales pointed out, these changes in soda sales were not caused by changes in retail prices. This led the authors to conclude that community education and media coverage of the campaign may have shifted social norms and affected sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among the UC Berkeley population shopping at campus stores.

Leading with Health Justice

Leading with health justice and engaging the community will significantly transform the ideas for tax measures, legislation, and campaigns, Morales concluded. He emphasized the importance of engaging the community in the process as early as possible, at the drafting stage, not after the measure has been written. Leading with health justice also generates good will and support for the measure. To garner that support, the communities that are bearing the burden of paying the tax need to be comfortable with where the money is going.

Pollution Regulation: Cap and Trade8

Pollution is a classic example of an externality, Fowlie said. Absent any regulation, producers and consumers do not factor in the damages associated with pollution in their production and consumption decisions. For example, a power plant does not think about pollution damages when making its production decisions, and consumers generally do not think about pollution damages when they are making energy purchase decisions. Pollution regulation was implemented to change behavior, either through regulated limits or through incentives. One approach is a carbon tax or a pollutant tax, where the social cost of pollution is estimated, and a corresponding tax is charged in an attempt to change behavior and influence consumption and production decisions.

Cap and Trade

Another approach is cap and trade. In this approach, regulators set a total limit on pollution, and distribute a corresponding number of permits to emitting industries that specify the limit on their emissions (the cap). Fowlie pointed out that cap and trade is similar to prescriptive regula-

___________________

8 This section is the rapporteur’s synopsis of the presentation made by Meredith Fowlie and James Sallee of UC Berkeley, and their statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

tions in that both specify a pollution limit that is not to be exceeded. The key difference, however, is that the cap-and-trade permits that specify the allowable emissions can be traded. This was done, in part, because it is difficult for a regulator to know how best to allocate the “right to pollute” to minimize the cost of achieving the emissions target. The more aggressive the targets, the higher the cost of meeting them, she said. The cap-and-trade approach harnesses the power of the market to seek out and deploy the low abatement costs first. In summary, she said, in a cap- and-trade program the right to pollute is allocated by awarding permits corresponding to the total emissions target, and firms are able to trade these permits in a market. In theory, industries reduce their own emissions to the extent that they can. At some point, continued reduction to meet the cap might no longer be cost-effective for a particular firm, and it can then purchase permit allowances from other firms that have reduced their emissions below their permitted cap.

Pollution, like income, is unequally distributed, Fowlie said. By some measures, pollution is more unequally distributed across communities than income. This is a concern because a lifetime of exposure to high pollution levels can significantly affect education, employment, and health outcomes. California has made it a priority to ensure that new environmental regulations address efficiency and cost-effectiveness, and improve conditions in disadvantaged communities. This can generate a difficult trade-off between minimizing the cost of meeting ambitious environmental and emissions targets and making sure that the benefits of reduced pollution are equitably distributed, she said. This trade-off highlights how important it is to carefully consider the consequences of policy decisions, she continued. She noted that economists favor the idea of using a market to allocate pollution reduction and abatement responsibilities and thereby minimize the costs of meeting the emissions targets. California is aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the state to 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030, which she reiterated is a very ambitious target. It is important to consider how to minimize the cost of meeting that target. However, the environmental justice community has argued that, while relying on market-based approaches may deliver the most cost-effective solution, it may not deliver the most equitable solution.

These environmental justice concerns become more complicated in the context of global climate change policy. Carbon pricing through cap and trade is targeting a global pollutant. For the climate damages associated with a ton of carbon, it does not matter where that carbon happens around the globe, Fowlie said. One might ask where local environmental problems fit in the context of global climate change policy. Fowlie explained that the local pollutants that are so problematic for low-income and traditionally disadvantaged communities (e.g., particulate matter, ozone precursors,

toxic substances) are often correlated with greenhouse gas emissions. There can be shared benefits to targeting global pollution in that reducing carbon can also involve reducing local pollutants. However, it cannot be assumed that reductions in carbon will lead to reductions in local pollution problems. For example, if a refinery wants to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions, it might do so by running the scrubber less often, as running the scrubber that removes sulfur dioxide or particulates from the emissions requires energy. Another reason why local pollution problems are part of the larger climate policy discussion is that local communities feel as though they do not have very much political power. Local communities have been trying to draw attention to local environmental problems for years, without much traction, Fowlie said. Communities in California realized that the state-level climate debate was an opportunity to steer the conversation toward local concerns.

The correlation between local pollution and global pollutants is not perfect, Fowlie said, and many economists are questioning why states are targeting local environmental problems with a policy tool that is aimed at the global greenhouse emissions problem. To address this, California is designing a cap-and-trade market-based program to deal with the carbon problem and coordinate abatement in the least costly fashion, and is committing the revenues generated to addressing the problems in local communities. Two bills are in progress. Assembly Bill 398 extends the cap-and-trade program. A companion bill, Assembly Bill 617, commits to increasing local monitoring of pollution, and to supporting local governance and local planning for addressing local health problems associated with co-pollutants and toxics. Funds from the revenues of the cap-and-trade programs are also earmarked for investments in environmental justice communities.

This is an opportunity, Fowlie concluded, to do a better job of monitoring exposures in these communities, to bring these communities to the table when a problem is identified and find a solution together, and to better understand the link between pollution and health outcomes in these communities.

Deploying the Revenue from a Selective Excise Tax

Sallee added his perspective on how to use the revenue resulting from a selective excise tax (i.e., sin tax), and the need to understand the heterogeneity across people in communities and how these tax policies affect them. As discussed, these types of policies are initially regressive. Whether it is a carbon or pollution tax, or a tax on alcohol, cigarettes, or sugary beverages, the initial burden of these policies will be disproportionately on low-income people, he said. These tax policies can be made progres-

sive, on average, by adjusting how that revenue is redistributed and used. Revenue from these taxes can be readily redistributed through program expenditures, or by simply giving money back to people by lowering their taxes or writing them a check, he said. For example, California has a modest cap-and-trade program that raises revenue and redistributes it in a twice yearly lump sum rebate that is credited to residents’ utility bills.

One aspect that is often overlooked, however, is that even if a policy has been implemented to be progressive on average, many low-income people will still be harmed because not all people are alike, Sallee said. Data show that the variation in consumption of taxed items within groups of people who are of similar income is much larger than the variation in consumption across income categories. There is significant heterogeneity in how much alcohol, cigarettes, or gasoline households of similar income consume. This means that, even though a policy might be progressive on average, so that low-income households are not hurt on average, it is very difficult to design a policy that distributes tax revenue so that no low-income households or communities experience a net harm. The data also suggest that only about 10 to 20 percent of this variation in consumption can be predicted (using a broad set of demographic variables that might be part of a tax system, such as income, household size, geographic location). Most of the variation is unpredictable, he said, and therefore is not easily targeted.

With regard to implementing a selective excise tax, Sallee noted that recent tax economics research has been focused on the salience of different taxes. In the context of a sugar-sweetened beverage tax or a cigarette tax, it is important that the tax be very salient, he said. Experimental evidence suggests that the tax should be assessed before the cash register (i.e., in the shelf price), because people are not as responsive to taxes that are added at the register.

In closing, Sallee said that economists increasingly have access to very granular data on who is affected by different policies and who benefits from which types of programs, as well as measurements of pollution, exposure, and consumption. Researchers are using tax data to measure the effect of different policies, and to link impacts or environmental exposures to long-term outcomes. Researchers are also using approaches, such as remote sensing satellite data, to measure pollution levels around the world and to study impacts and exposures. As a result, theoretical insights will increasingly be able to be associated with empirical measurement to inform better design of tax policy, as well as better evaluation.

Politics of Taxes

In response to a question about the strategy behind the Berkeley win where 30 others had failed, Morales elaborated that every locality is

complex and is going to have a different view of what is “political good” versus the “public health perfect.” Continuing to push for public health perfection can decrease the chances of winning if this “perfect” does not reflect local realities that will be expressed through the ballot box. Pamukcu added that, in achieving the political good, it is better to avoid earmarking these taxes as one-for-one, for example, taxing sugary drinks and earmarking the money specifically for obesity prevention. Rather, in Philadelphia for example, the revenues from the sugar-sweetened beverage tax go toward prekindergarten programs and neighborhood infrastructure improvements. There is a real opportunity to think creatively about what the community wants in a public health context, she said, and not necessarily create a one-for-one substitution.

A participant said that, in her prior experience, arguments that these selective excise taxes are regressive were countered with the fact that the associated conditions (e.g., alcoholism) are also regressive, and she asked if that argument was still economically valid. Morales agreed that diseases are regressive, however, in his experience, that argument does not influence legislators. These taxes exist in a political world, and it comes down to power. He said that, in his experience, educating and mobilizing the community so that they are making the requests of their legislators was a lot more effective than a third party lobbying on the idea that these diseases are more regressive than the tax. He also reiterated that, if the community is being held up as the justification for the tax, it is essential that the funding be targeted to community priorities. Too often these communities feel used politically because the money ultimately goes elsewhere. Sallee added that the distribution of the benefits is often difficult to measure. While the argument that the diseases are regressive is factually true, it is not a particularly persuasive argument. He added that the argument is not necessarily relevant for carbon, except to the extent that carbon reductions might also reduce other pollutants that have local effects.

Pamukcu agreed that the best approach to resistance from industry and legislators is to stop talking about the vulnerable population in theory, and to actually get them to the policy making table to speak for themselves and their interests. She emphasized the need for both community education and community partnership. Education flows in one direction. Partnership implies that we also want to hear and learn from them. Partnership empowers communities to determine and articulate their priorities for themselves.

Marice Ashe of ChangeLab Solutions raised the issue of preemption in the context of politics. She explained that when communities start becoming successful in passing these taxes at the local level, powerful industry lobbying leads to preemption that overrides the local ability for local control over outcomes. Community engagement can be helpful in fighting

against a preemption, but it is very expensive and time consuming. The industry can move more quickly, and with more money, than public health can. She noted that this is not limited to public health, and it also affects economic justice issues and environmental justice issues, for example. If there were to be a preemption, Morales suggested activating the same groups that were successful at the local legislative level and bringing them to the table at the state level. Those local groups that support the need for the tax are the ones that need to talk to the legislators. Pamukcu highlighted the need to work together beyond public health, and to pull together the sophisticated pockets of specialized advocates into a much broader coalition that can effectively mobilize against preemption.

EXPLORING TAX CREDITS TO FINANCE POPULATION HEALTH INVESTMENTS9,10

Tax credits are used extensively, Becker said, but not often with the explicit purpose of benefiting population health. There is a range of population health interventions that offer impressive opportunities to improve health and lower cost, but there is no functioning market for them. Tax credits offer one way of developing this market. Some tax credits are effective, while others are not, and Becker emphasized that the design of a tax credit program is paramount. There is an opportunity to redeploy tax credit funds to not only to improve population health, but to improve the returns for taxpayers.

To illustrate the concept of tax credits for population health, and to set the stage for the small group activity (see Chapter 4), Becker began by briefly describing how the hypothetical state of “Ourlandia” came to consider tax credits to fund its population health needs (see Box 3-2 and Appendix C).

The Tax Credit Landscape

As shown on the typology of tax policy options (see Figure 1-1), a tax credit is one form of tax policy known as tax expenditures, which are more commonly known as tax breaks. Tax expenditures include

___________________

9 This presentation was adapted from a ReThink Health paper in development, Exploring the Potential of Tax Credits for Funding Population Health, which was provided to workshop attendees. A working draft of the paper is available at https://www.rethinkhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/RTH-ExploringTaxCredits_v11282017.pdf (accessed February 2, 2018).

10 This section is the rapporteur’s synopsis of the presentations made by Stacy Becker of ReThink Health, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

- tax deductions, which are certain expenses that can reduce taxable income (e.g., home mortgage interest, charitable contributions);

- tax exclusions, in which certain types of income are excluded from taxable income (e.g., Social Security income); and

- tax credits, which are a dollar-for-dollar reduction on tax liability.

Tax expenditures are heavily used, Becker said. At the federal level, there are more than 200 different types of tax breaks, which are claimed on 169 million tax returns. More than $1.5 trillion in tax expenditures was

projected for 2017. State-level tax expenditures are similarly expansive, and most states issue detailed tax expenditure reports.

Despite the extensive use of tax credits at both the federal and state levels, there are very few tax credits for interventions for population health and the social determinants of health. As discussed earlier, the EITC and the LIHTC are examples of federal tax credits with some relation to population health. At the state level, Massachusetts has a tax credit for lead abatement, New Hampshire has a tax credit for opioid program coordination, Arizona has a tax credit for antipoverty organizations, and Colorado has a tax credit for early childhood education. Becker added that there is nothing that enables the funding of local portfolios for health and well-being.

Tax credits essentially operate like a rebate program, Becker explained. The federal solar tax credit gives solar energy system purchasers a 30 percent tax credit, for example. If an individual spends $10,000 on solar panels, then $3,000 can be deducted from the federal tax they owe. The intent was that tax credits would subsidize private investment (e.g., it reduces the overall cost to the individual of installing solar panels). By reducing the costs, it increases the return on investment to private investors (the benefits are the same, but their cost was reduced). This then stimulates supply and demand for these types of goods.

Becker described an opioid program as an example of a public health intervention that could be used in a tax credit portfolio. The costs of this particular program are $356 per person on average. And the benefits are split, with $379 in health care savings for taxpayers and $383 in savings for health insurers. Most would look at those numbers and feel they could make better investments with their money, Becker said. There are many positive externalities associated with this program, including both financial and social benefits; however, no one invests in this program. When a 50 percent tax credit is implemented, the costs are split. Because taxpayers get half of the costs back as a tax credit, they are now paying $178. The returns look much more appealing, people want to invest, and then the benefits of the positive externalities can accrue to the communities.

Tax Credit Design

The design of a tax credit program is extremely important. Experience shows that some tax credit programs achieve their objectives and others do not. For example, the LIHTC is an effective federal tax credit that has produced a great deal of affordable housing, Becker said, although there are some unintended consequences. At the other end of the spectrum are certain business incentives at the state level that have not been very effective.

Becker highlighted several key design questions that need to be considered in creating a tax credit for population health:

- Is there a taxpayer? Becker pointed out that many population health interventions are provided in the public sector or by nonprofit organizations. A tax credit only works if someone is paying taxes,11 she said, as it does not have any value to someone who has no tax liability.

- Is there a market for population health? For a tax credit to work there must be a specific supply and demand for something. A tax credit is a subsidy and an incentive.

- How big should the subsidy be? Because a tax credit should function as an incentive, it should not pay people for something they are already doing. A tax credit that is set too low has no effect as an incentive.

- What are the distributional impacts? Who gets to claim a tax credit? Who benefits from the distribution of funds? How are the funds from the credit used? This is where unintended consequences can come into play, Becker noted.

- What does it take to administer the tax credit? Some tax credits are very straightforward (e.g., solar tax credit), while others are very complicated. The LIHTC is very expensive to administer because it creates a tradable financial asset, Becker said. It created an entire new industry in the home market, with lawyers and financiers needed to make it work.

- How do we know it is achieving its aims? Becker cautioned that critics of tax credits will claim that tax credits are not very accountable; however, accountability can be built into a tax credit.

Becker noted that there is the opportunity to potentially redeploy the investment of existing tax credit funds. With regard to the design of business incentives, for example, Becker said there is a growing consensus that they are not achieving their intended purpose. Around $45 billion is spent annually on state and local incentives for businesses. Recent studies have shown that incentives, such as the creation of enterprise zones and empowerment zones, do not correlate with unemployment, income, or future economic growth, and do not necessarily further distributional goals of reducing poverty in the zones.

___________________

11 Tax credits also may be syndicated or sold to a third party who assumes tax liability; this process is commonly used with LIHTC (see, for example, https://www.nationalequityfund.org/whoweare/aboutlihtc [accessed June 8, 2018]).

Tax credit programs are feasible, Becker concluded. She reiterated the need to pay careful attention to design, and to look for the opportunity to redeploy funds for greater effect.

Prototype Tax Credit: Healthier Workforce Tax Credit12

Following the overview of tax credits by Becker, Burke presented a prototype tax credit program developed by ReThink Health for discussion. The Healthier Workforce Tax Credit is a tax credit for self-insured employers to broaden their investments in health. Specifically, it would provide a 50 percent tax credit to self-insured employers who invest in a certified, curated portfolio of interventions for employees and their families who they cover. Burke reviewed the design of the prototype relative to the six key design questions outlined by Becker:

- Taxpayer: Self-insured employers.

- Market: There is currently a $6 billion employee wellness program market that could be tapped.

- Size of the tax incentive: A 50 percent tax credit. The actual return on investment is dependent on what interventions the employer invests in, for how many employees, for how long, and other factors.

- Distributional effects: Limited to those who are employed by the self-insured employer, and their families.

- Administration: Fairly simple.

- Accountability: Employers choose from a portfolio of state-certified interventions with a demonstrated return on investment; there is a cap on the annual state budget for this tax credit, and a cap on the amount that employers could claim on their annual tax return based on the number of employees covered; there are annual reporting requirements for the employers and for the state department of health. The program is scheduled to last 5 years, after which it could be revised and continued as determined by evaluation of annual reports.

This idea could work, Burke said, because an estimated 100 million Americans are covered by self-funded employer plans. Employers who take on the risk of providing insurance to their employees have a business incentive for keeping their costs down as this directly affects their cash

___________________

12 This section is the rapporteur’s synopsis of the presentation made by Nina Burke of ReThink Health, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

flow. This tax credit would increase their return on investment because the benefits remain the same from whatever programs they invest in, but the tax credit directly reduces the up-front costs.

As mentioned previously, there is no perfect tax credit, Burke said, and there are potential challenges to be addressed up front. For example, employers would likely prefer short-term investments that are predictable and for which they can budget. In addition, this program will not reach the full population, only those employees who are covered and their families. Another concern is that employers select the interventions to provide their employees, which may or may not align with what the community actually needs.

In a perfect world of perfect tax credits, Burke said, a tax credit scheme such as this would lower health care costs for both employer and the employee; reduce absenteeism and increase productivity; prevent chronic disease; lead to an overall healthier workforce in the region and thereby increase regional economic productivity; and reduce social expenditures to the state and increase tax revenue because healthier people are working more and working longer. The ultimate indicator of success, she concluded would be a return on investment for all parties involved.

Prototype Tax Credit: People’s Choice Health Investment Credit13

McIntosh provided an overview the second prototype tax credit program drafted by ReThink Health. The People’s Choice Health Investment Credit uses charitable tax credits to fund “wellness funds” that would operate as part of accountable communities for health (ACHs). She reviewed the design of the prototype relative to the six key design questions outlined by Becker:

- Taxpayer: Both individuals and corporations, to provide the widest catchment possible to maximize the amount of funds.

- Market: Significant. Charitable giving was about $354 billion in 2014, and donations continue to grow.

- Size of the tax incentive: The approach is stratified to appeal to both individual and corporate donors, McIntosh explained. Research indicated that individuals responded more positively to programs that had lower caps combined with a higher tax credit (i.e., charitable giving increases with higher tax breaks). Individuals would

___________________

13 This section is the rapporteur’s synopsis of the presentation made by Amanda McIntosh of ReThink Health, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

-

receive a 50 percent tax credit, increasing over 5 years to a maximum of 62 percent. Corporations would have a higher cap, and would receive a 40 percent tax break, increasing over 5 years to 52 percent.

- Distributional effects: Donation might vary by wealth of the community.

- Administration: Straightforward administration through tax returns. (Requires state certification of eligible, evidence-based interventions.)

- Accountability: Donations are made to wellness funds that are operated by a state-certified ACH. Funds are used for state-certified, evidence-based interventions. The program lasts 5 years (and may be renewed), and annual reporting is required.

There are several potential challenges, McIntosh said. There is likely to be unequal distribution across the state, as some regions might be more civically minded or philanthropic than others, and some regions have higher concentrations of wealthier individuals. To enhance equity, the program would require each wellness fund to remit a portion of their funds back to the state for reallocation to areas receiving fewer contributions. Another challenge is that the program is reliant on other infrastructures, including the wellness funds, the ACH, and the state government. Most importantly, she said, the program is reliant on donor behavior and the ability to market the value of contributing to a wellness fund to diverse taxpayers. She added that many taxpayers have not heard of wellness funds. Finally, maintaining sustainability is a challenge, and the program design attempts to encourage sustainability with the graduated tax increase.

Charitable tax credits are a viable approach to funding population health interventions as states already operate similar targeted charitable tax credit programs (e.g., supporting antipoverty programs). Charitable giving is extremely popular in the United States and is growing. McIntosh noted, for example, that much of the response to the devastation of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico has come from wealthy individual private donors or crowd-sourced philanthropy. In addition, the donor base is expected to grow as millennials are set to inherit trillions of dollars in generational wealth over the next three to four decades. Research suggests that they are interested in investing their money on harm reduction and progressive causes, and they want to see a return on investment.

Success of the program would ultimately lead to achieving better health outcomes and reducing health care costs, McIntosh said. If successful, the program would also solidify a sustainable backbone resource (the wellness fund) and improve equity by creating local and inclusive control through the model of an ACH wellness fund.

Summary

Becker reiterated that tax credit programs are feasible, and that the effectiveness of these programs is highly contingent on design. Health is economic development, she said, and population health offers opportunities for higher returns than other current tax credit investments. As discussed throughout the workshop, many of the opportunities rest at the state level, she said. There are state funds that could be redeployed, and the requirement for annual balancing of state budgets leads to an interest in programs with high returns on investments. States are also becoming very aware of the broad benefits of investing in a healthier population.

In closing, Becker provided a comparison of taxes and tax credits (see Table 3-1).

Discussion

Following the presentations, participants raised several topics for discussion, including aspects of returns on investments and leveraging existing tax credits.

TABLE 3-1 Comparison of Taxes and Tax Credits

| Taxes | Tax Credits | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Source of funds | Amount owed to the government | More | Less |

| Participation | Mandatory | Voluntary; relies on incentives | |

| Design | Relatively easy | Relatively difficult | |

| Who invests | Government (taxpayers) | Government leverages private funds (taxpayers co-invest) | |

| Revenue predictability | Fairly predictable | Uncertain in early stages | |

| Use of funds | Decision making for use of funds | Centralized through government | Distributed through private sector |

| Amenable to portfolio approach | Yes | Limited situations | |

| Potential scope of interventions | Broad | More narrow | |

| Review | Annual budget setting | No annual review |

SOURCES: Becker presentation, December 7, 2017. Reproduced with permission from The Rippel Foundation. The Rippel Foundation is not providing an endorsement of the content within this presentation and provides permission for this to be used for non-commercial purposes only.

De Biasi suggested that tax credits might create a market that solves the “wrong pocket problem,” which is when the savings and benefits from implementing an intervention do not accrue to the investor (i.e., the return on investment goes into the wrong pocket). A good population health investment creates a range of benefits, such as reduced health care costs, improved health, longer lives, increased income, or decreased criminal justice costs, Becker said. Those benefits are distributed, however, and it is not clear that any one sector benefits. A tax credit reduces the cost of investing in an intervention, making investments seem less risky, and offering some sort of payback in the short term, instead of waiting for outcomes to accrue. A tax credit could incentivize investments by hospitals, health plans, and others that they might otherwise not be willing to make because the returns are either too far out, or they will only receive a portion.

A participant highlighted the need to take the social return on investment into account, in addition to the financial return on investment. Tax policies incentivize certain behaviors that society deems good, such as home ownership. However, the population health discussions seem focused on the need to show a financial return on investment. He acknowledged that revenue is clearly needed, but he felt the focus on a financial return on investment was worrisome, and suggested that it will limit the kinds of interventions that could be supported, some of which might be of greater value to society. Becker agreed, and referred to Morales’s discussion of balancing politics and policy. This is the starting place, she said. Proposals focus on financial return on investment to convince policy makers of the value, with the hope that they will at least invest in the minimum portfolio, and then investments that achieve social return on investment will follow.

A participant observed that, in the proposed tax credit for the wellness fund, a corporation donates to the wellness fund and the government gives them back a tax credit, and they suggested that perhaps it would be more direct for the government to simply fund the wellness fund.

Another participant suggested that existing tax credits could be leveraged for population health purposes. For example, many states are eager to encourage new entrepreneurial businesses, and perhaps provisions related to job development for underrepresented populations could be incorporated into incentives for new businesses. Becker said she was not aware that this had been done, but that there has been discussion around adding on to LIHTC. Tax credits allow for creativity, she said, and added that it is important to understand the state conditions, infrastructure, and political environment, as well as the tax structures that could be built off of or shaped around them. A participant pointed to the evidence that the EITC is effective at reducing poverty and inequality. As poverty

and inequality are key drivers of health inequities and poor outcomes, she suggested expanding something that already exists and is known to work, like the EITC. Becker agreed that the EITC is an important tax credit and should certainly be supported by population health. She felt that the focus of the workshop discussions was to find ways to fund interventions addressing other social determinants of health. De Biasi referred participants to a recent report from TFAH, Pain in the Nation, for a chart listing the EITC by state and whether it is refundable (TFAH, 2019). She noted that this could be a resource to identify states needing advocacy attention in this area.