Appendix D

Technical Appendixes to Select Chapters

APPENDIX D, 2-1

A BRIEF HISTORY OF POVERTY MEASUREMENTS IN THE UNITED STATES

The nation’s Official Poverty Measure (OPM), developed in the 1960s by Mollie Orshansky of the Social Security Administration, is based on research showing that, in the 1950s, the average family spent about one-third of its after-tax income on food (Fisher, 1992). Orshansky then multiplied the cost of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s “basic” diet food plan by three to calculate poverty thresholds for families of different compositions and sizes (she used somewhat different methods for families of one and two people). Families with resources (regular money income as measured in a supplement to the Current Population Survey) below these amounts were considered to be poor. These thresholds have been adjusted for inflation every year using the Consumer Price Index. The official poverty rate is calculated in essentially the same way now as it was in the 1960s.

This approach to measuring poverty has numerous shortcomings: It is based on the now outdated assumption that families spend one-third of their post-tax income on food (today they spend less than one-half that amount); it fails to adjust for geographic differences in living costs; and, more importantly, it counts neither in-kind benefits nor refunded tax credits as income. Thus, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the Child Tax Credit, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, child care assistance, subsidized housing, and many other in-kind benefits are ignored in computing the poverty rate. It is also an absolute poverty

measure in that the poverty thresholds are updated for inflation but not for changes in the country’s standard of living.1

These problems with the OPM were considered serious enough to generate congressional interest in an improved measure. Funding from a provision in the Family Support Act of 1988, which mandated a National Research Council study of a national minimum benefit standard for the now defunct Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) Program, combined with funding from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Department of Agriculture, supported the work of an NRC panel of poverty experts. This panel produced an influential report, Measuring Poverty—A New Approach, in 1995.

Despite the attention generated by that panel’s report, the OPM remains unchanged for many reasons, two of which are of major importance. First, numerous pieces of legislation stipulate that cash grants are to be provided to states, cities, and school districts, and the allocation of those grants is often based on the area’s poverty rate. Changing the poverty measure used in allocation formulas would affect the distribution of money among states and local areas, substantially in some cases.

Relatedly, the official poverty thresholds (actually a variant of them) are used to determine eligibility of families for a number of assistance programs. Second, defining a poverty level requires making judgments. Given the financial stakes of determining who is poor and who is not, Congress would certainly be mired in a long and contentious debate if it sought to set new poverty thresholds or change other aspects of the official measure.

Nonetheless, following the 1995 report, analysts at the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics began the complicated work of implementing many of the report’s recommendations for improving the measurement of poverty. By 2011, after more than a decade of study, the Census Bureau released a new method of defining poverty. The title of the new measure—the “Supplemental Poverty Measure” (SPM)—made it clear that the federal government, and in particular the Census Bureau, was not proposing to replace the OPM with a new one, but rather adding a new measure that would advance research and provide additional information for policy discussions.

___________________

1 Because the inflation index used for the Official Poverty Measure (OPM) overstated price changes for a period, the official thresholds have actually been updated to some extent in real terms—that is, for changes in living standards. See Appendix D, 2-2, for a discussion of absolute versus relative poverty measures and the use of different inflation measures for adjusting thresholds.

APPENDIX D, 2-2

TYPES OF INCOME-BASED POVERTY MEASURES AND THE ADVANTAGES OF USING THE ADJUSTED SPM FOR POLICY ANALYSIS

Poverty measurement requires a set of decisions about the purpose and specifications of the measure. As background, Box D2-1 defines key terms in poverty measurement, such as threshold and resource concepts and whether the measure is intended to be absolute or relative. It also briefly defines types of poverty measures, including economic measures, such as those based on income or consumption, and other kinds of deprivation and hardship indexes.

The committee’s charge is to identify and estimate the benefits and costs of government policy and program options that can reduce child poverty and deep poverty in the United States within 10 years and to propose practical measures to do so given the available data. For this purpose, it is necessary to use an income-based economic poverty measure, which can clearly show the effects of one or another policy option on the adequacy of families’ resources. Other types of measures, such as deprivation and material hardship indexes, add to the picture of families’ living situations and well-being but present challenges to any straightforward estimation of the effects of government tax and transfer policies on them. This is also a limitation at present of consumption-based economic poverty measures—see Appendix D, 2-3.

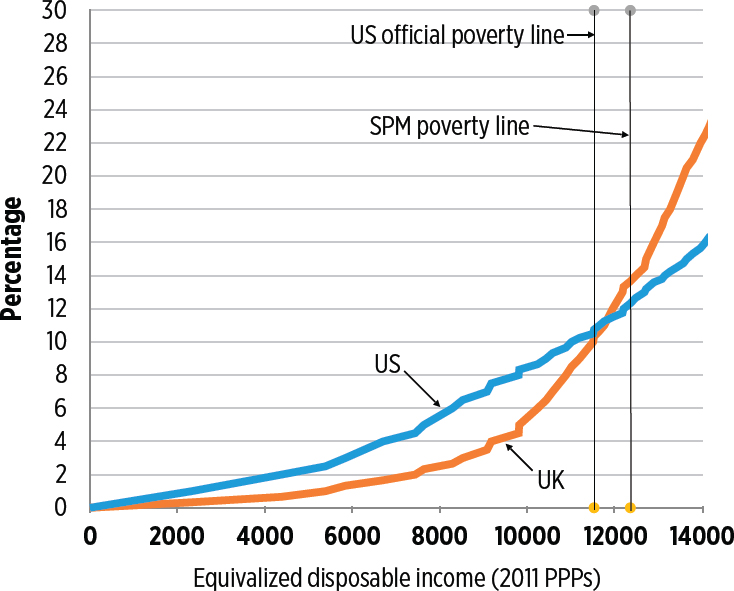

The committee’s charge directs us to base our analyses on the income-based SPM and not on either the OPM or a consumption-based poverty measure. Unlike the Census Bureau, we use an adjusted SPM, in which we correct the underlying data for some types of income underreporting using the Urban Institute’s Transfer Income Model, Version 3 (TRIM3) microsimulation model. This appendix section describes and assesses the OPM, the SPM, and the adjusted SPM. It then discusses several contentious issues for income-based poverty measurement: relative versus absolute poverty; inflation adjustments; and the implications for income-based poverty, particularly deep poverty, of error in the underlying data source—the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC). See Appendix D, 2-3, for a discussion of consumption-based poverty measures, for which issues of relative versus absolute poverty, inflation adjustments, and data quality are also relevant.

Three Income-based Poverty Measures: OPM, SPM, Adjusted SPM

The OPM, the SPM, and the adjusted SPM used in this report are based on resources defined by a family’s income. A family is defined as poor if

family income is below a specific cutoff. The cutoff is chosen to indicate the income needed to attain a minimum or basic level of goods and services. This simple description masks the many specific decisions that are required to define an acceptable, feasible, and useful income-based poverty measure. Table D2-1 compares the OPM, the SPM, and the adjusted SPM on 11 dimensions: uses, measurement unit, threshold concept, threshold adjustments, threshold updating, treatment of health benefits and costs, resource measure, reference period, metric(s) estimated, data source, and data quality.

Three key differences between the OPM and the SPM merit fuller discussion: the type of measure (absolute or relative), the threshold concept, and the definition of family resources. Other important differences—in the adjustments to the thresholds for family composition and the unit of measurement—are briefly described in Table D2-1.

Type of measure. The OPM officially became an absolute measure in 1969, when proposals to update in real terms the original 1963 thresholds (based only on food needs—see next section) were turned down because policy makers were reluctant to show any increase in poverty.2 Since then, the thresholds have been updated for inflation only, using the flagship series published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics—the All Items Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, known as the CPI-U. Overestimation of inflation in the CPI-U, however, resulted in real increases to the thresholds in the 1970s and early 1980s (see discussion of inflation indexes below).

The SPM, in contrast, is a quasi-relative poverty measure in which the thresholds are based on needs for a specific set of goods—but a broader set than food—and are recalculated every year as spending on those goods changes. It is similar to an absolute measure because the thresholds are

___________________

2 See https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/1995/demo/fisher3.pdf. Between 1963 and 1969, changes in the costs of Economy Food Plan were used to update the thresholds.

TABLE D2-1 Dimensions of Three Income-Based Economic Poverty Measures: Official Poverty Measure (OPM), Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), Adjusted SPM

| Measure/Dimension | Official Poverty Measure | Supplemental Poverty Measure | Adjusted SPM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinds of Uses | Statistical (from 1967 in annual Census Bureau publications): —monitor trends over time and among population groups and geographic areas—see Ch. 2 Research: —study how child poverty affects child (e.g., health) or longer-term adult (e.g., employment) outcomes—see Ch. 3 —aggregate over families in neighborhoods (e.g., census tracts) to study effects on outcomes—see Ch. 8 Policy: —determine eligibility for government programs —simulate effects on poverty of existing and proposed programs and policies that affect cash income |

Statistical (from 2011 in annual Census Bureau publications): —monitor poverty trends over time and among groups (see Fox et al., 2015, for series back to 1967 using an anchored SPM); for geographic areas, the Fox et al. anchored SPM series is available by state, and some states and cities have developed SPM estimatesa Research: —too new to be used for long-term outcomes research Policy: —growing uses, which can include simulation of full range of government policies and programs that affect disposable income (e.g., tax credits, SNAP) |

Policy: —used in TRIM3 model to simulate effects of programs and policies with a more accurate income measure (see Resource Measure below) |

| Measure/Dimension | Official Poverty Measure | Supplemental Poverty Measure | Adjusted SPM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comment: | OPM is used extensively because of its official status; ill-designed for monitoring differences among groups and areas and for policy analysis because it neglects importance sources of government income support and nondiscretionary costs (see Resource Measure below) | SPM could be used as extensively as OPM; well designed for policy analysis of effects of government benefits delivered in-kind and through tax credits (see Resource Measure below); would likely be improvement over OPM for outcomes research (although any reasonable way to identify low-income groups can work) | Same as SPM with advantage of providing a more accurate income measure (see Resource Measure below) |

| Measurement Unit | Family (individuals related by birth, marriage, or adoption co-resident in the same house) or unrelated individual age 15 or older living in a house | Resource unit (official family definition plus any co-resident unrelated or foster children under age 18, or unmarried partners and their relatives) or other unrelated individual age 15 or older | Same as SPM |

| Comment: | Does not define poverty for unrelated children in a house (e.g., foster children) under age 15; does not include anyone living in an institution (e.g., prison) or who is homeless. These limitations are inherent in the underlying data—see Data Source below | “Family” definition is more inclusive than OPM and thereby responds to societal changes, such as the increase in the number and percentage of cohabiting partners with children; does not include people living in prisons or other institutions or homeless people | Same as SPM |

| Poverty Threshold Concept | Three times the cost of a minimum food diet in 1963, derived from the ratio of all (after-tax) spending to food spending for families in a 1955 survey (a so-called “expert” budget method of establishing poverty thresholds) | Based on expenditures for food, clothing, shelter, and utilities (FCSU), and a little more, derived from Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE) data for the 33rd percentile of FCSU spending by families with 2 children. The multiplier for “a little more” is 1.2 | Same as SPM |

| Comment: | Threshold concept is outdated: today, families spend 8 times the cost of food consumed at home or eaten outside | Covers broad set of basic necessities (about 45% of total spending); 33rd percentile validated by comparison with other types of income-based thresholds and assistance program needs standards (see National Research Council, 1995, Ch. 2) | Same as SPM |

| Threshold Adjustments | Vary by family size, composition, and age of householder (see App. D, 2-4) | Vary by family size and composition (see App. D, 2-4) and tenure (rent, own home with mortgage, own home free and clear); also vary geographically by differences in housing costs (see App. D, 2-5) | Same as SPM |

| Comment: | Method to determine family size/composition threshold adjustments produced hard-to-justify variations; no adjustment for geographic variations in costs of living | Equivalence scale used for family size and composition adjustments well justified; adjustments for housing cost differences across areas address largest component of spending | Same as SPM |

| Threshold Updating | CPI-U (flagship index published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics) | 5-year moving average of expenditures on FCSU (each year in a 5-year average is updated to the most recent year using the CPI-U) | Same as SPM |

| Measure/Dimension | Official Poverty Measure | Supplemental Poverty Measure | Adjusted SPM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comment: | OPM is an absolute poverty measure with thresholds updated only for inflation since 1963; because the CPI-U was corrected for overestimation of inflation, the OPM thresholds are estimated to have actually increased in real terms (see text) | SPM is a quasi-relative poverty measure with thresholds updated for changes in real spending on necessities on a lagged basis; does not depend on an inflation measure except to adjust 5 years of CE data in calculating each year’s thresholds | Same as SPM |

| Treatment of Health Care Costs and Benefits | OPM thresholds implicitly include a small amount for out-of-pocket medical care spending; resources ignore health care benefits and costs | SPM thresholds explicitly exclude health care insurance premiums and other out-of-pocket medical care costs; resources deduct out-of-pocket costs | Same as SPM |

| Comment: | OPM ignores expansion of health care benefits and costs | SPM treats out-of-pocket medical care costs as nondiscretionary but ignores expansion in health care benefits; National Research Council (1995, pp. 223-237) recommended a separate “medical care risk index” | Same as SPM |

| Resource Measure (to compare to threshold) | Gross before-tax regular money income (see App. 2-5) | Disposable income: sum of regular money income, plus noncash benefits that resource units can use to meet FCSU needs, minus taxes (or plus tax credits), minus work expenses, out-of-pocket medical expenses, and child support paid to another household (see App. D, 2-6) | Same as SPM except for adjustments for underreporting of certain income types (see Data Quality below) |

| Comment: | Gross money income concept relevant in the 1960s before expansion of government assistance through in-kind programs and tax credits, but outdated today; captures effects of economic cycles but not of important programs or nondiscretionary expenses | Disposable income concept is relevant today | Same as SPM with the advantage of correcting for some kinds of income underreporting |

| Reference Period | Calendar year | Calendar year | Calendar year |

| Comment: | Annual is standard reference period; estimates have been constructed for poor months over a year or poor years over a period (e.g., childhood) | Same as for OPM; little use made to date of SPM for measuring short-term or long-term poverty | Same as SPM |

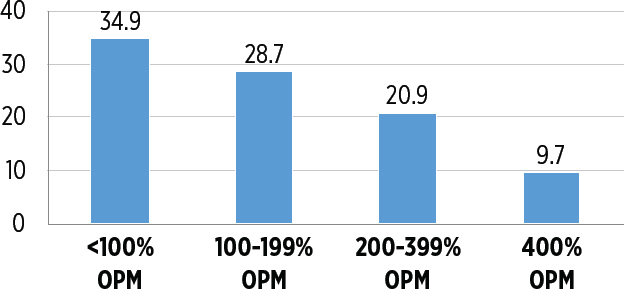

| Metric(s) estimated | Statistics typically presented as ratios of income to the poverty threshold: less than 50% (deep poverty); less than 100% (poverty); 100–150% (near poverty); poverty gap sometimes calculated (aggregate amount of income by which families are below poverty) | Same as OPM | Same as SPM |

| Comment: | Additional metrics could be calculated (see National Research Council, 1995, Ch. 6) | Same as OPM | Same as SPM |

| Data Source | Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC)—sample of 100,000 households | Same as OPM, but uses additional CPS-ASEC data, such as in-kind benefits and nondiscretionary expenses; tax credits/debits are modeled by the Census Bureau | Same as SPM with some kinds of income adjusted for underreporting |

| Measure/Dimension | Official Poverty Measure | Supplemental Poverty Measure | Adjusted SPM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comment: | OPM measures have been constructed with many datasets—e.g., ACS for small-area estimates and SIPP for part-year estimates | SPM measures have been constructed with SIPP and, by some states and cities, with ACS (often augmented with administrative data to fill in ACS gaps) | Could be constructed with other datasets |

| Data Quality | CPS ASEC obtains high response rates but exhibits underreporting of many income types, even after imputation (which itself can create error) of amounts for respondents reporting receipt (see text) | Same as OPM | Adjusts three income types for underreporting: SNAP, SSI, and TANF (see text) |

| Comment: | Quality concerns with income data in the CPS (ACS and SIPP have similar problems) are an important disadvantage of the OPM (see text) | Same as OPM | Some but not all quality concerns are reduced because of adjustments |

NOTE: ACS = American Community Survey; CPI-U = Consumer Price Index-Urban Consumers; NRC = National Research Council; SIPP = Survey of Income and Program Participation; SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; SSI = Supplemental Security Income; TANF = Temporary Assistance to Needy Families.

a See, e.g., https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/24401/904570-Expanded-Poverty-Measurement-at-the-State-and-Local-Level.PDF [January 2019].

SOURCE: Compiled by committee staff from Census Bureau and other sources.

based on a specific set of needs, but it has an element of a relative measure because the thresholds change as spending on those goods changes over time in the U.S. population. The SPM consequently does not require an inflation index per se except to make all 5 years of Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE) data used in constructing the thresholds consistent in real terms.3 The recalculation of SPM thresholds every year is intended to produce a conservative or quasi-relative measure compared with a relative measure, such as a percentage of median income (see discussion of absolute vs. relative measures and inflation indexes below).

Threshold concept. The OPM thresholds, developed originally for 1963, represent a type of “expert budget.” Specifically, U.S. Department of Agriculture nutritionists costed out a basic food plan (the Economy Food Plan) that would be minimally nutritious and palatable. Mollie Orshansky at the Social Security Administration multiplied the cost of the food plan for different sizes and compositions of three-or-more-person families by three to allow for all other needed spending, using the spending patterns of the average family in 1955 as the basis for the multiplier. She used a different method for two-person families and single individuals, with lower thresholds when such a family was headed by someone aged 65 or older, on the grounds that their food needs were less.

The SPM thresholds, in contrast, allow for the costs of a much broader bundle of basic needs, including food, clothing, shelter, and utilities (FCSU), plus a small multiplier (1.2) to account for other necessary items, such as non-work-related transportation and personal care. The FCSU component is based on actual consumer expenditures for families with any number of adults and two children at the 33rd percentile of the distribution. A lower percentile is not used because families’ spending could be constrained by their income, and therefore a lower percentile could underestimate their basic needs. The thresholds for two-child families are calculated separately for renters, homeowners with a mortgage, and homeowners who own their homes free and clear. Homeowners without mortgage debt have a lower threshold than the other two groups because their out-of-pocket housing needs are less. A formal equivalence scale is used to adjust the SPM thresholds for different sizes and composition of families (see Appendix D, section 2-4), and, finally, the thresholds are adjusted for geographic variations in the cost of housing (see Appendix D, section 2-5).

Resource concept. The OPM has a limited measure of family resources, namely, regular money before-tax cash income, which was the definition used for data collection in the CPS. The definition was not unreasonable at the time before the expansion of tax credits and in-kind benefit programs.

___________________

3 That is, the thresholds rise over time in response to price increases only to the extent that the prices of the basic goods rise.

The SPM defines resources (see Appendix D, section 2-6) to recognize that substantial government assistance is provided to families through the tax system and in-kind transfers, such as housing subsidies, free school lunches, and SNAP (formerly food stamps). The SPM uses a disposable money and near-money income resource definition, not only including the cash value of such programs as SNAP and lump sums received as tax credits, but also recognizing that some expenses are nondiscretionary. Specifically, the SPM definition subtracts work-related expenses including transportation and child care, child support payments to another family, out-of-pocket medical care payments (including premiums, co-pays, deductibles, and uncovered care), and net taxes (federal income and payroll and state income) after credits. This definition provides a much more realistic picture of families’ resources for their everyday needs for food, clothing, shelter, utilities, and a little more.

The adjusted SPM is the same as the SPM published by the Census Bureau with one important exception. The TRIM3 model used by the committee for its analyses adjusts three types of government transfers for underreporting by survey respondents, using aggregate totals from administrative records as benchmarks. These three sources are SNAP, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF). They contribute importantly to low-income families’ resources and also suffer from significant and increasing underreporting in the CPS ASEC and other surveys (see discussion below).

Key Issues for Economic Poverty Measurement

This section discusses three key issues that are sources of debate in evaluating not only the OPM, the SPM, and the adjusted SPM, but also consumption-based measures (see Appendix D, section 2-3). They are absolute vs. relative measures; inflation indexes; and the implications of the well-documented underreporting of income in surveys for poverty measurement, particularly deep poverty.

Absolute vs. Relative Measures

The OPM is intended to be an absolute poverty measure even though the thresholds were inadvertently adjusted in real terms because of problems with the CPI-U used to update them for inflation. Recent work on consumption-based poverty also uses an absolute measure, or more precisely, an anchored measure (see Appendix D, section 2-3).

An absolute measure may make sense for monitoring poverty trends for a period of time because it affords a fixed standard of need. In contrast, relative measures offer a moving target, which may be less intuitive to the public and policy makers. Maintaining an absolute measure over long

periods, however, can give results that do not square with contemporary perceptions of deprivation and are not helpful for policy. The National Research Council (1995, Figure 1-1) illustrated this phenomenon by comparing the OPM two-adult/two-child threshold with a subjective threshold derived from public opinion and a threshold (similar to that used in many countries) of 50 percent of median after-tax money income, all in constant 1992 dollars. In 1963, all three thresholds were in agreement, but in 1947, the other two thresholds were only 68-75 percent of the OPM threshold. In contrast, by 1970, the other two thresholds exceeded the OPM threshold by 20 percent (National Research Council, 1995, Tables 2-3, 2-4).

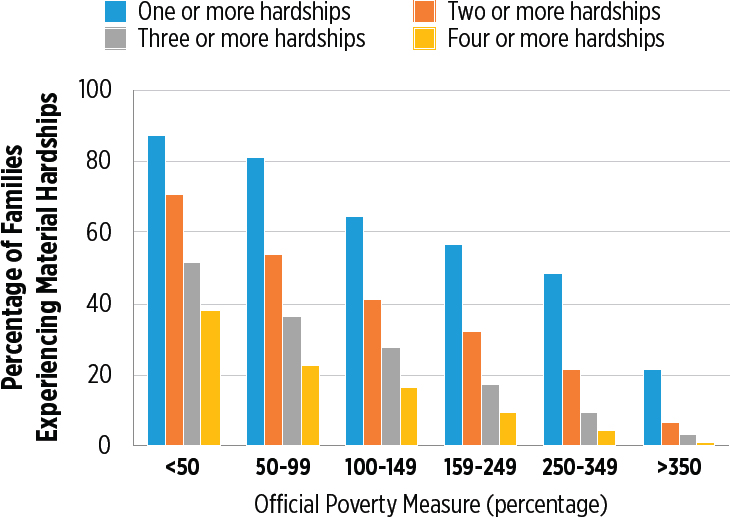

At the heart of the difference between absolute and relative poverty measures is whether the basic needs that society deems that every family should have should be allowed to change over time. This is most clearly illustrated by the concept of deprivation and material hardship (see Appendix D, Box 2-1). Arguments have been made, by looking at such deprivation measures as material hardship, that the poverty rate is not as high as the OPM or even an income-based measure corrected for income underreporting would indicate (see, e.g., Meyer and Sullivan, 2011). For example, more lower-income families had air conditioning and other appliances in 2009 compared with 1980 (the period studied in Meyer and Sullivan, 2011), and using an absolute measure poverty declined between those years. More generally, living standards overall have increased over the past 30 years for the entire population. Yet that increase does not mean that an absolute poverty measure, established 30 or 40 years in the past, is necessarily preferable to a relative or quasi-relative measure, because what is regarded as a basic need by society generally increases along with living standards.

An historical example is telling in this regard: In 1940, 45 percent of U.S. households lacked complete plumbing facilities compared with only 7 percent in 1970 shortly after the OPM was adopted.4 Yet it is unlikely that a 1940 poverty threshold would have been set so as to result in a 45 percent poverty rate. Conversely, the OPM threshold set in 1963, which was universally felt to be “right” at the time (see National Research Council, 1995, p. 110), gave a poverty rate for 1970 of 12.6 percent, almost twice as high as the percent of households then with inadequate plumbing. Moreover, as noted above, by 1969 the OPM threshold itself was viewed as too low, and today basic budgets constructed by nongovernmental organizations, when expressed in comparable terms, are as high as the SPM thresholds, which represent a real increase over the OPM thresholds (see, e.g., the “Household

___________________

4 See https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/housing/census/historic/plumbing.html.

Survival Budget” calculated for counties in 18 states as part of the United Way ALICE Project).5

The National Research Council (1995) study that recommended a new poverty measure, which with some modifications became the SPM (see Appendix D, 2-1), did not recommend a completely relative measure, such as a percentage of median income, as used in many other countries (see Appendix D, 2-11). Instead, it recommended what it termed a “quasi-relative” updating procedure, based on changes in consumption of basic necessities (food, clothing, shelter, and utilities) in the lower part of the distribution of consumer expenditures as measured in the CE. The 1995 study (Ch. 2) cited evidence that subjective thresholds, based on public opinion, lagged increases in median income as support for its supposition that a quasi-relative updating procedure would be more acceptable to the public and policy makers. It further cited evidence that real increases in consumption on necessities lagged real increases in total expenditures as measured in the Bureau of Economic Analysis Personal Consumption Expenditures series as justification for its recommended updating procedure.

Inflation Indexes

All poverty measures that have any absolute element, including anchored measures, require a measure of price change or inflation to keep their thresholds constant in real terms. It is well known that the CPI-U, which is used to adjust the OPM thresholds each year, has overstated inflation in the past. BLS maintains the CPI-U-Research Series (CPI-U-RS) to provide a historical series that estimates improvements in the CPI-U back through 1978, with the CPI-U-RS reestimated annually to incorporate as many additional improvements in the CPI-U as is feasible. Most, but not all, of the improvements reflected in the CPI-U-RS produced lower inflation rates relative to the corresponding CPI-U, often significantly so prior to 2000. Since 2001, the two series are very similar.

In 2002, BLS introduced a chained CPI series, the C-CPI-U, which lowered inflation even more than the CPI-U-RS by more fully capturing consumers’ ability to substitute among items in the face of price changes. In 1999, a method for capturing substitution within item categories was introduced into the CPI and CPI-U-RS; the C-CPI-U, also beginning in

___________________

5 ALICE stands for Asset-Limited, Income-Constrained, Employed, as the focus of the ALICE Project is on the working poor; see https://www.unitedwayalice.org/overview. Note that alternative basic budgets typically need to have several components subtracted for comparability with the SPM thresholds—e.g., child care, work-related transportation, medical care, and taxes must be subtracted from the ALICE Household Survival Budget because these items are subtracted from SPM resources and are therefore not included in SPM thresholds. Interestingly, the Household Survival Budget includes smartphone costs as a basic need.

1999, uses in addition a method for capturing substitution among item categories.6 Between 1999 and August 2017 (the latest estimate available), the C-CPI-U has averaged 1.9 percent inflation per year, compared with 2.2 percent for the CPI-U and the CPI-U-RS between 1999 and 2017.7

Whether the official poverty thresholds should be adjusted with the C-CPI-U rather than the CPI-U, or whether they should be adjusted with an index that exhibits even less inflation than the C-CPI-U, are questions for further research.8 The SPM does not require an inflation index, except to make all 5 years of CE data used in the threshold calculations expressed in the same dollars and except when SPM thresholds are anchored for purposes of historical analysis (see Appendix D, 2-10), although its thresholds do rise over time as the price of its basic necessities rise in addition to rising because of increased consumption (in real terms) of these necessities.

Data Quality and Deep Poverty

Chapter 2 notes the extent of income underreporting in the CPS ASEC for many types of income and not just those accounted for in the adjusted SPM. Researchers (e.g., Winship, 2016; Appendix D, 3-1) have cited underreporting as a reason to doubt estimates of deep poverty, even with TRIM3 adjustments to some types of income. Meyer and Sullivan (2012a; online appendix table 10), using the 2010 CE, find that families in deep poverty with an SPM measure (unadjusted for underreporting) do not lack for amenities (e.g., major appliances) any more than officially deeply poor families. Further analysis would be required to assess these findings using the adjusted SPM measure, which in our analysis yields a very low deep poverty rate for children in 2015—2.9 percent—compared with a rate of 4.9 percent with the unadjusted SPM and a rate of 8.9 percent for the official measure.

Yet, cognizant that problems in income reporting could affect our estimates of adjusted SPM deep poverty, given the low thresholds involved (about $13,000 for two-adult/two-child renters and owners with a mortgage in 2015), we investigated further the characteristics of deeply poor

___________________

6 See https://www.bls.gov/cpi/additional-resources/chained-cpi-questions-and-answers.htm.

7 The C-CPI-U historical series is available at: https://www.bls.gov/cpi/additional-resources/chained-cpi-table24C.pdf; the CPI-U and CPI-U-RS calculations are derived from a spreadsheet provided by Bruce Meyer and James Sullivan to the committee in an e-mail, January 8, 2019.

8 Indeed, there are many reasons for research into the effects of using different price indices in measuring well-being over time for specific populations. For instance, some think that the prices paid by poor people differ from those paid by rich people.

families with children in 2015.9 We found evidence of anomalies resulting from the treatment of self-employment income in the CPS ASEC. Thus, deeply poor children in families with self-employment income made up 12.6 percent of the deeply poor group (15% of these families, or 1.9% of all deeply poor, had negative self-employment income). The CPS ASEC asks respondents for their profit or loss from self-employment, which means that many self-employed people may report accounting losses (or a lesser amount of profit) when they have not, in fact, experienced real declines in their ability to meet their needs.

We also found anomalies in the case of interest and dividend income. Thus, 28.1 percent of deeply poor children lived in families receiving dividends or interest (although two-thirds of these families had their dividend or interest income imputed by the Census Bureau). Examining the distribution of interest and dividends (imputed and reported), the dollar amounts for most families were small (the 75th percentile value for deeply poor children was $142, compared with $109 for poor children and $1,200 for all children). But there were outliers with relatively high amounts of dividend income (the 90th percentile value for deeply poor children was $1,559, compared with $1,001 for poor children and $5,879 for all children). These results suggest that some imputations of high values for interest and dividend income may have been made erroneously, especially given that the 90th percentile values for deeply poor children in families with reported interest and dividends were several hundred dollars lower than those for imputed and reported combined. It is also likely that at least some deeply poor families with income from such sources as self-employment and interest and dividends were not usually poor, let alone deeply poor, but had a below-average year with high out-of-pocket medical care expenditures or work expenses that pushed them into deep poverty.

Our very preliminary analysis suggests that further research is needed into the characteristics of children living in families classified as deeply poor under the adjusted SPM. Research is also needed on better ways to collect self-employment income in the CPS ASEC and to evaluate imputation procedures to be sure they take relevant variables into account and do not impute high values of such sources as interest and dividends inappropriately.

Advantages of the Adjusted SPM for Policy Analysis

From what is known about the strengths and weaknesses of the three income-based poverty measures reviewed above, the committee concludes

___________________

9 Results presented for self-employment and interest and dividend income were performed at the committee’s request by the Urban Institute using TRIM3.

that for its purpose of analyzing government policies and programs that can reduce income-based child poverty:

- The SPM is preferable to the OPM because, among other improvements, it includes “near-cash” benefits from SNAP, housing subsidies, and other assistance programs and from refundable tax credits. It also accounts for costs of work, such as day care. By contrast, the OPM counts only regular gross money income and thereby overstates the extent of child poverty and underestimates the positive effects of government programs in reducing child poverty. Critical for the committee’s purposes is that the OPM cannot be used to estimate the effects on child poverty of policy or program options that involve in-kind benefit programs or tax credits.

- The adjusted SPM is preferable to the unadjusted SPM because of its corrections for underreporting of income from SNAP, SSI, and TANF in the CPS ASEC, which has worsened in recent years.

- The adjusted SPM shares some of the drawbacks of the SPM (and the OPM) as a measure of income, namely:

- The adjusted SPM (also the SPM and OPM) underestimates the poverty-reducing effects of medical care coverage, such as from Medicaid and Medicare (see Ch. 7 for a proposed solution).

- The adjusted SPM does not correct for underreporting of sources of income other than SNAP, SSI, and TANF, including underreporting of market income.

- The adjusted SPM (also the SPM and OPM) may overestimate the extent of deep poverty as a result of how certain kinds of income are collected in the CPS ASEC, such as self-employment losses, and as a result of error in imputations for families reporting receipt but not amounts of some income types. These problems could be ameliorated with research and improvements to the quality of CPS ASEC income data (see Ch. 9).

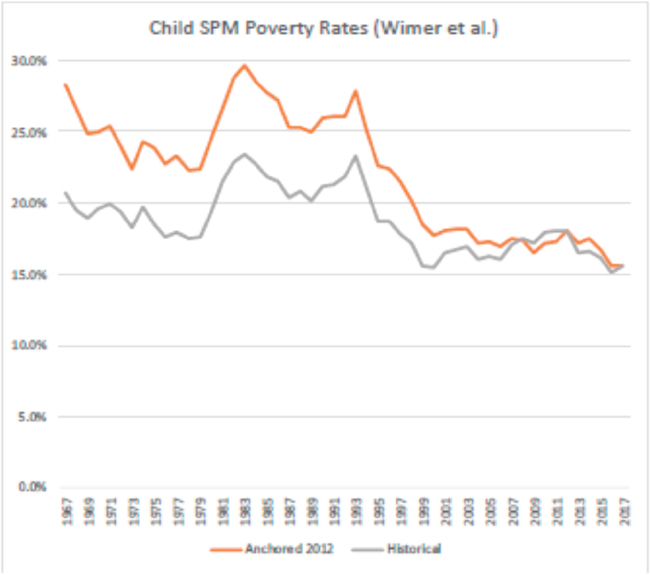

Finally, we note that parts of our report rely on the OPM or an anchored (unadjusted) SPM. For example, our review in Chapter 3 of the literature on the consequences of child poverty for outcomes necessarily uses the OPM, because the SPM has not been available for a long enough period for outcomes research. While the SPM (even better, a fully adjusted SPM) would be an improvement over the OPM, any reasonable measure of low income can suffice for this type of research. Our review of trends in child poverty in Chapter 4 uses an unadjusted SPM anchored in 2012, because TRIM3 adjustments to the SPM are not available historically. Consequently, the poverty rates shown are somewhat higher than they

would be with the adjusted SPM, but there is no reason to believe that the overall trends are invalid (see Appendix D, 2-10). None of our simulated packages in Chapters 5 and 6—and therefore none of our calculations for which programs would reduce poverty by 50 percent—use the OPM or an anchored SPM. In addition, as experience is gained with the SPM going forward, particularly if our recommendations in Chapter 9 for improvements to the CPS ASEC are adopted so that the SPM can be derived from complete income information, we are confident that the SPM will continue to be useful and informative for research and policy.

APPENDIX D, 2-3

CONSUMPTION-BASED POVERTY MEASURES

All of the economic poverty measures discussed in Appendix D, 2-2, use variants of an income-based measure of resources. An alternative approach to economic poverty measurement is to use a family’s consumption rather than its income to capture family resources. In this appendix, we discuss the definition of consumption poverty, how it has been measured, and the arguments in favor of a consumption-based poverty approach. We also discuss a number of problems with implementing a measure of consumption-based poverty using data currently available from the federal statistical system.

Most economists believe that consumption is a better measure of well-being than income because their theories consider a family’s well-being (“utility”) to be generated by the goods and services consumed by the family. If, over the course of every month, a family consumes exactly 100 percent of its monthly income, then income and consumption would be equal and would indicate the same level of well-being. But incomes can fluctuate from period to period. Provided that a family is able to save its income and/or access credit from one period to the next, it should be able to “smooth” consumption against income fluctuations, which would produce more stable and consistent amounts of monthly consumption than would be indicated by monthly income. If smoothing is feasible for families, then consumption should provide a better measure of well-being.

In practice, however, low-income families have little in the way of assets and savings (see Ch. 8), so it is unclear whether the low-income families with children who are the focus of our report can do much, if any, smoothing (Hurst, 2012, p. 191). Indeed, to the extent that families facing declining income maintain their consumption by such strategies as unsecured credit, pay-day loans with high interest rates, and the like, a consumption-based poverty measure may not provide as timely an indicator of when low-income families are under increasing financial stress as an income-based poverty measure, assuming good measurement of income.

As detailed in the main body of Chapter 2, a practical challenge with income poverty measurement in the United States is significant underreporting of government transfers and other kinds of income in the CPS ASEC and other household surveys (Meyer, Mok, and Sullivan, 2009, 2015; Moffitt and Scholz, 2009; Wheaton, 2008). A potential advantage of a consumption-based definition of poverty stems from more complete survey reports of expenditures than income. Thus, Meyer and Sullivan (2003, 2011) find that expenditures (and consequently consumption, which is derived from expenditures) appear to be better measured than income in the CE for lower-income Americans (although CE income is less well reported than CPS ASEC income).10 It is not known how much of the difference is a result of underreporting of conventional sources of income in the CE versus families’ not being asked to report or not reporting less conventional sources, such as unsecured credit and gifts or short-term loans from relatives and friends, as income.11

The CE has a number of drawbacks for measuring consumption poverty. It collects data on expenditures and asset holdings but not consumption per se. A comprehensive consumption measure requires imputing service flows to such assets as housing, vehicles, and consumer durables (e.g., appliances) and may also involve subtracting some types of expenditures because they are viewed as investments or for other reasons (see below). As with income data in all government household surveys, expenditures in the CE are underreported and are subject to important measurement error, attrition bias, and nonresponse bias (National Research Council, 2013).

The CE also has much smaller sample sizes than income surveys such as the CPS ASEC and especially the American Community Survey (ACS).12 Thus, in its current form, the CE is not well suited to generate subnational estimates for poverty; in fact, the public-use version of the CE does not even identify state of residence. The CE data, in their current form, also are challenging to work with because they must be assembled for five quarters to measure consumption during a calendar year for a consumer unit (a family

___________________

10 Once the CE began in 2004 to impute amounts for people who said they had income but did not provide an amount, the ratio of CE income to CPS/ASEC income rose from under 80 percent to about 95 percent across all income types; see https://www.bls.gov/cex/twoyear/200607/csxcps.pdf, text Table 4.

11 The CE Interview Survey questionnaire module on income asks about lump sum payments from “persons outside your household” as part of a broad question on lump sum income; the CE Interview Survey asset and liability module asks about balances on credit cards, student loans, and all other loans, including personal loans, but this information is not integrated with “income” for purposes of comparing with expenditures (see https://www.bls.gov/cex/capi/2017/2017-CEQ-CAPI-instrument-specifications.pdf).

12 The CE Interview Survey obtains about 7,500 consumer unit interviews per quarter, compared with the CPS ASEC’s 94,000 household interviews per year and the ACS’s 2.2 million household interviews per year.

or one or more people in a household who share income). Alternatively, quarters of expenditures can be pooled and annualized. This approach (used by Meyer and Sullivan in their studies—see below) maximizes the available sample but may not produce the same results as if expenditures were constructed for the same consumer units over the year. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has a program under way to redesign the CE to improve its measurement of expenditures and related information, but implementation will take a number of years, and there is unlikely to be expansion of the sample.13

Most recent research on using the CE to measure trends in consumption inequality that attempts to correct for the CE’s measurement errors shows that consumption inequality tracks income inequality very closely through the mid-2000s (Attanasio and Pistaferri, 2016). Meyer and Sullivan (2017) show that the two measures diverge after approximately 2006, although they use a nonstandard price index (see below), which accounts for a good part of the divergence.

Meyer-Sullivan Consumption-Based Poverty Measure

Meyer and Sullivan, in a series of studies (Meyer and Sullivan, 2012b, 2017, 2018), use the CE to measure consumption poverty across groups and over time. They construct poverty thresholds by finding the threshold (after equivalizing consumption using equivalence scales from National Research Council, 1995) that leads to the same consumption and income poverty rates in some base year. They adjust the threshold from one year to the next using an inflation index that subtracts 0.8 percentage points per year from the All Items Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers-Research Series (known as the CPI-U-RS—see Appendix D, 2-2). Meyer and Sullivan (2012b) term this a “bias-corrected” CPI-U-RS (see further discussion below).

Using 1980 as the base year, Meyer and Sullivan (2018, Table 3) find that in 2017, 3.5 percent of children are poor based on their measure of consumption poverty compared with 9.4 percent based on their measure of income poverty. They measure income poverty using an after-tax-and-transfer resource measure that has some similarities to but is not the same as the SPM (see Box D2-2). Comparing the two series over time, their consumption and income poverty measures track each other fairly closely until 2000, when their child income poverty measure flattens out (as does the SPM), whereas the consumption-based measure of child poverty continues to decline steadily. They use the same inflation index, namely, their bias-corrected CPI-U-RS, for both series, so the sources of the difference

___________________

in trends must be due to other factors. Some possible explanations include these: the CE could have experienced an increasing rate of income underreporting after 2000 (similar to the CPS ASEC);14 homeowners could have given increasingly inflated estimates of the rent they expect their homes would bring;15 other expenditures could have become better reported over time;16 consumption, perhaps supported by credit, could have grown markedly faster than income; or some combination of these and other factors.

Comparing Meyer and Sullivan’s consumption measure for the whole population with the OPM using CE income data (they do not show results for the OPM comparison separately for children), the two measures track each other fairly closely until 1990, when the OPM poverty rate remains fairly steady, whereas the consumption rate declines steadily and substantially. By 2017, OPM poverty for the entire population was 12.3 percent compared with 7.0 percent for their income measure compared with only 2.8 percent for their consumption measure (Meyer and Sullivan, 2018, Table 1). The continued higher poverty rate for the OPM not only reflects the factors that account for the difference between Meyer and Sullivan’s income and consumption measures, but also two other factors: (1) increases in noncash benefits (e.g., SNAP) and tax credits over the period, which are not included in the OPM resource measure; and (2) the “bias-corrected” CPI-U-RS price index used by Meyer and Sullivan in contrast to the OPM, which uses the CPI-U (see further discussion below).

Meyer and Sullivan’s work uses an anchored measure of consumption-based economic poverty. In anchored measures, the starting (or ending) threshold value is selected to facilitate analysis of trends rather than on the threshold’s merits in level terms (see Appendix 2-2). For their series anchored in 1980, Meyer and Sullivan selected their threshold to give the same 13 percent poverty rate as the OPM. Consequently, their threshold was at the 13th percentile of the distribution of their measure of consumption, which amounted to $8,100 for a two-adult/two-child family in 1980

___________________

14 Meyer, Mok, and Sullivan (2009, Tables 2-9) show increased underreporting in both surveys over the 1990s and through 2006–2007 compared with earlier years for transfer program income, including SNAP and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families. Whether 2000 is the precise inflection point for marked deterioration in reporting would require closer examination of the data.

15 With regard to housing, the ratio of the CE estimate of imputed homeowners’ rent to the comparable estimate from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) personal consumption expenditures (PCE) series rose continuously from the mid-1990s to as high as 120 percent in the mid-2000s, falling back during the Great Recession (see Bee, Meyer, and Sullivan, 2012, Figure 1a). The ratio has stayed constant for 2014–2018 at 110 percent (see https://www.bls.gov/cex/cepceconcordance.htm).

16 The evidence on the accuracy of CE reporting of various expenditures, relative to the BEA PCE series, beginning in 2000 is mixed—with some types of expenditures exhibiting better reporting and others worse (see Bee, Meyer, and Sullivan, 2012, Figures 1a–1i).

dollars. That threshold was 97 percent of the official poverty threshold of $8,350 for 1980.17 The Meyer and Sullivan approach thus shares the OPM defect of using absolute needs in a particular year and then deriving poverty rates in other years without any direct assessment of whether needs are changing, unlike what is done in the SPM.

Further, Meyer and Sullivan did not assess basic consumption needs against their 1980 thresholds to see if the thresholds made sense relative to living standards at the time. Yet by 1980 it was clear that the OPM

___________________

17 The 97 percent figure is from Meyer and Sullivan (2012b, footnote 7); 1980 official poverty thresholds are available at https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/1982/demographics/p60-133.pdf; the threshold cited in the text is for “other” nonfarm families with four members, including two children.

thresholds fell considerably below other kinds of thresholds, such as those based on one-half of median income or those derived by asking samples of people their assessment of a poverty line (so-called subjective thresholds—see Appendix 2-2).

As it turned out, using their “bias-corrected” CPI-U-RS inflation factors, Meyer and Sullivan’s two-adult/two-child threshold for the current end point in their series (2017) was $17,765, which was only 71 percent of the comparable OPM threshold of $24,858.18 Yet they intend their

___________________

18 The Meyer and Sullivan threshold for 2017 was derived using deflators provided by Bruce Meyer and James Sullivan in an e-mail communication, January 9, 2019; 2017 official poverty thresholds are available at https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-263.pdf.

series not only for analytic purposes (as in the committee’s use of anchored SPM thresholds—see Ch. 2 and Appendix 2-10), but also as the basis for a substantively meaningful poverty series for policy makers. Given how their anchored thresholds were developed, it is hard to know how to assess the face validity of their thresholds either in 1980 or today.

Meyer and Sullivan’s use of their “bias corrected” CPI-U-RS is a major reason for the marked decline in poverty observed in their consumption-based measure. It is well known that the CPI-U has overstated inflation in the past and that BLS has endeavored to correct the CPI-U going forward. BLS produces the CPI-U-RS as a historically comparable series back to 1978 that incorporates the latest CPI-U improvements. BLS also, beginning in 1999, has produced a chained CPI-U (C-CPI-U), which corrects for a remaining source of overstatement of inflation in the CPI-U (the C-CPI-U averages about 0.3 percentage points per year below the CPI-U—see Appendix 2-2).

Meyer and Sullivan rely on several studies of bias in the CPI-U for their decision to subtract 0.8 percentage points per year from each year’s growth in the CPI-U-RS. The studies include Berndt (2006), the Boskin Report (Advisory Commission to Study the Consumer Price Index, 1996), and Hausman (2003). Berndt (2006), which reviewed what was done to improve the CPI-U following the Boskin report and other studies, found that BLS had made and was continuing to make major improvements. Meyer and Sullivan’s bias correction, which is applied at the same rate every year, does not have a direct basis in any particular prior study.

Whether there is justification for the sizeable correction Meyer and Sullivan make for upward bias in the CPI-U and CPI-U-RS is unclear and would require more study.19 More study would also be needed to investigate the optimum schedule for updating poverty thresholds in real terms—continuously as in the SPM and percentage-of-median income measures (which do not rely on an inflation measure); close to 40 years (as in the Meyer-Sullivan consumption measure); 55 years as would be the case for the OPM if the CPI-U had not been found to overestimate inflation; or a shorter interval. Suffice it to say that the use of the bias-corrected CPI-U-RS by Meyer and Sullivan to keep their 1980 threshold constant over almost 40 years produces contemporary thresholds and poverty rates that seem unrealistically low compared with other thresholds and rates.

It should also be emphasized that the method of anchoring used by Meyer and Sullivan makes the actual poverty rate in any given year an

___________________

19 Researchers often prefer the PCE deflator produced by BEA, which generally increases at a lower rate than the CPI-U (see, e.g., Winship, 2016). It also differs significantly from the CPI in scope (e.g., including medical care costs paid for by insurers) and other features, so that its advantages for adjusting poverty thresholds are not clear. See, for example, Johnson (2017).

arbitrary function of the anchoring year chosen. For example, if Meyer and Sullivan anchored their consumption poverty series in 2015 instead of 1980, they would conclude that the poverty rate in 2015 is the same as the OPM poverty rate—13.5 percent—and not the 3.4 percent they obtain for 2015 when anchoring in 1980. But that would imply that their poverty rate in 1960–1961 was as high as 62 percent (see Meyer and Sullivan, 2018, Table 2). Thus, their inflation index results in either implausibly high 1960–1961 poverty rates or implausibly low contemporary poverty rates, depending on the anchoring year chosen.

Reasons to Use the Adjusted SPM for This Study

For the purposes of our report, we do not use a consumption measure of poverty for four reasons:

- The TRIM3 model adjusts the CPS ASEC for underreporting of three major types of transfer income, thereby addressing a large component of the problem with the use of income survey data.

- The available data on consumption have the measurement issues discussed above.

- Because the congressional charge to our committee is to assess how current and alternative transfer and other programs might change poverty, using a consumption poverty measure would require knowing how changes in those programs would affect consumer expenditures, and the research base on that relationship is scant and far from sufficient to use as a basis for simulations. Moreover, while the effect of transfers on income is conceptually straightforward and mostly mechanical, the effect of transfers on consumer spending requires understanding individual behavior and necessarily requires a higher level of research understanding than for income.

- The Statement of Task for our committee directs us to use a specific income-based measure of poverty.

Taking this all into account, income poverty measured with the adjusted SPM is the appropriate measure for our use. The ability to incorporate corrections for underreporting of government transfers, using the TRIM3 model, is clearly crucial. A longer-term solution is to invest in improving our household surveys for income measurement—see Chapter 9. In fact, there is significant effort at the Census Bureau to incorporate administrative data into household surveys to do just that. Initial work by Meyer and coauthors (Meyer and Mittag, 2015; Meyer and Wu, 2018) shows that this is feasible and can lead to important findings on the measurement of

poverty and the evaluation of the antipoverty effects of government tax and transfer programs.

Work to improve the CE for measurement of expenditures and related information, as is currently under way at BLS, is also a worthwhile investment in an important component of the suite of essential federal statistics for research, public understanding, and policy analysis. The 1995 National Research Council report that recommended what became the SPM in fact recommended (p. 13) improvements in the CE that could support consumption-based poverty measures. Further research on how to relate changes in government policies and programs to consumption would also be very worthwhile.

APPENDIX D, 2-4

HOW EQUIVALENCE SCALES ARE USED TO ADJUST POVERTY THRESHOLDS

The resources needed for a family to achieve a basic standard of living, however defined, vary with the size and composition of the family. Expenditures on some basic need categories, such as shelter and utilities, may not increase dramatically with a marginal increase in household size; meanwhile, expenditures on other basics, such as food and clothing, may be more sensitive to the number of people in the household.20

Since the amount spent on some necessities by larger families is greater than the amount spent by smaller families, poverty thresholds based on a 5-year moving average for consumption of food, clothing, and shelter must be adjusted to reflect the differences. Equivalence scales are typically used to make these adjustments so that families of various sizes and composition may be compared on as equal a basis as possible. The OPM thresholds, however, were constructed using a different approach (see National Research Council, 1995, Ch. 3).

As described in the first section of Chapter 2, for the SPM the poverty threshold is based on the 33rd percentile of expenditures on FCSU for resource units (families),21 multiplied by 1.2.22 The SPM poverty threshold is estimated using 5 years of data from the CE on out-of-pocket FCSU spending by household units with one or more adults and exactly two children; this is referred to as the resource threshold for the reference family.

___________________

20 Although, even in these cases, economies of scale may be realized. Consider hand-me-downs, which allow expenditures on clothing for a second child to be lower than those for the first child, or the fixed costs associated with preparing a meal for, say, five versus four people.

21 The expenditures on FCSU include the value of spending funded through in-kind subsidies for SNAP, school lunches, WIC, and rental subsidies (Garner, 2010).

22 In contrast, for the OPM, the threshold is defined as three times the cost of a minimum food diet (as established in 1963); see App. D, 2-2, for more detail.

A different reference threshold value is calculated for renters, owners with mortgages, and owners without mortgages.

A “three-parameter” scale is used to adjust the reference threshold to families of differing size and composition mix, specified as follows (Short, 2001):

- Scale for units with one and two adults = (number of adults) 0.5

- Scale for single parent units = (number of adults + 0.8 * first child + 0.5 * number of other children) 0.7

- Scale for all other families = (number of adults + 0.5 * number of children) 0.7

The equations contain both “multipliers” (as in 0.8 and 0.5 in the second equation) and “exponents.” The 0.8 and 0.5 multipliers recognize that children do not consume as much as adults (who are assigned a multiplier of 1.0). The exponents 0.5 and 0.7 recognize that the additional costs of adding a member to the resource unit decreases with the number in the resource unit; in other words, the per-unit cost of basic needs decreases with household size. The threshold resource level for the reference family is multiplied by the resulting equivalence scale to determine the thresholds for each combination of family size and composition.

Table D2-2, displays the equivalence scaling ratios for selected family types relative to that of the reference family. So, for example, to achieve the poverty threshold, a one-parent, two-child family is assumed to require about 83 percent of the level of resources required by a two-parent, two-child family. In 2015, the reference renter family is assigned an SPM threshold of $25,583, estimated using the CE.23

Table D2-3, provides a comparison of the SPM equivalence scale to the equivalence scales implicit in the three government benefit programs: the EITC, SNAP, and the Child Tax Credit (CTC).

APPENDIX D, 2-5

COST-OF-LIVING ADJUSTMENTS IN POVERTY THRESHOLDS AND BENEFITS

The cost of maintaining a given standard of living changes over time and varies from place to place. In the case of the former, prices may rise (or fall) from one period to the next, meaning that an individual or household requires more (or less) nominal income to purchase a similar “basket” of goods and services. Regarding change by place, the cost of purchasing a

___________________

23 This is the figure for renters—the threshold for owners with a mortgage is about the same, and the threshold for owners without a mortgage is quite a bit lower than the $25,583 figure.

TABLE D2-2 SPM Equivalence Scales by Household Size, 2015

| Household Size | Implied Equivalence Scale | 2015 SPM Thresholds |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Parent, 1 Child | 69.94 | $17,891.94 |

| 2 Parents, 1 Child | 88.02 | $22,517.73 |

| 1 Parent, 2 Children | 83.03 | $21,241.05 |

| 2 Parents, 2 Children | 100.00 | $25,583.00 |

| 1 Parent, 3 Children | 95.29 | $24,376.83 |

| 2 Parents, 3 Children | 111.39 | $28,497.99 |

SOURCE: Fox (2018).

similar market basket may vary from one city, state, or country, to another. Cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) are used as a method to equate dollar amounts, in terms of purchasing power, either temporally or spatially; they are often applied to payments such as those made for wage contracts.

However, with the exception of SNAP, none of the cash or near-cash benefits paid to low-income people, including the EITC and the CTC, contains any set of regional COLAs. The benefits are the same nominal amount across the entire nation. The only exception is public housing allowances, which are implicitly tied to the cost of rentals and which vary widely across the nation. In this appendix section, we explore these differences in the treatment of COLAs on the threshold side and the benefit or income side of income-based poverty measures; we also describe how the OPM and SPM address COLAs.24

The Role of COLAs in Setting Poverty Thresholds

While the income thresholds (the boundary designating who is and is not living in poverty) established by the Census Bureau’s OPM are updated to account for price inflation over time (using the CPI-U), they do not include adjustments to account for geographic differences in the cost of living. As a result—assuming the measurement goal is to provide an accurate perception of the relative economic well-being of populations across the country—in high-cost states the OPM undercounts the number of people living in poverty, and in low-cost states it overcounts them, relatively speaking.

By contrast, the income thresholds set by the SPM are designed to incorporate changes in the standard of living over time and are also

___________________

24 SNAP contains a modest adjustment for differences in housing costs across areas by allowing for deductions (against earned income) for shelter cost.

TABLE D2-3 Implied Equivalence Scales for EITC, CTC, and SNAP Programs by Household Size

| Household Size | Basic SPM Equivalence Scale | Implied EITC Equivalence Scale | Implied CTC Equivalence Scale | Implied SNAP Equivalence Scale | Max EITC Credit 2016 | Max CTC | SNAP Max Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Parent, 1 Child | 69.94 | 60.53 | 50 | 55.01 | $3,373 | $1,000 | $ 4,284 |

| 2 Parents, 1 Child | 88.02 | 60.53 | 50 | 78.74 | $3,373 | $1,000 | $ 6,132 |

| 1 Parent, 2 Children | 83.03 | 100.00 | 100 | 78.74 | $5,572 | $2,000 | $ 6,132 |

| 2 Parents, 2 Children | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100 | 100.00 | $5,572 | $2,000 | $ 7,788 |

| 1 Parent, 3 Children | 95.29 | 112.51 | 150 | 100.00 | $6,269 | $3,000 | $ 7,788 |

| 2 Parents, 3 Children | 111.39 | 112.51 | $6,269 | $3,000 | $ 9,252 |

SOURCE: Committee-generated, using data from Tax Policy Center (2017).

partially adjusted to reflect geographic differences in families’ living costs. The SPM income thresholds are based on a measure of resources required to purchase necessities—food, clothing, shelter, and utilities—at a basic level, as estimated using the previous 5 years of CE data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.25 They are re-estimated every year instead of being adjusted for inflation. The SPM thresholds generally, but not always, show a greater year-to-year increase than the OPM thresholds, indicating that living standards are outpacing inflation.

The geographic COLAs in the SPM compensate for differences in the price of rental housing, as measured by the median rent index, across areas. The median rent index is the ratio of the median outlays by renters for rent and utilities (for a two-bedroom unit with complete kitchen and plumbing facilities) in a specific metropolitan area or state to the median outlays nationwide for the same type of unit (Renwick, 2018). Rental price data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey are used to adjust the housing component of the poverty thresholds.

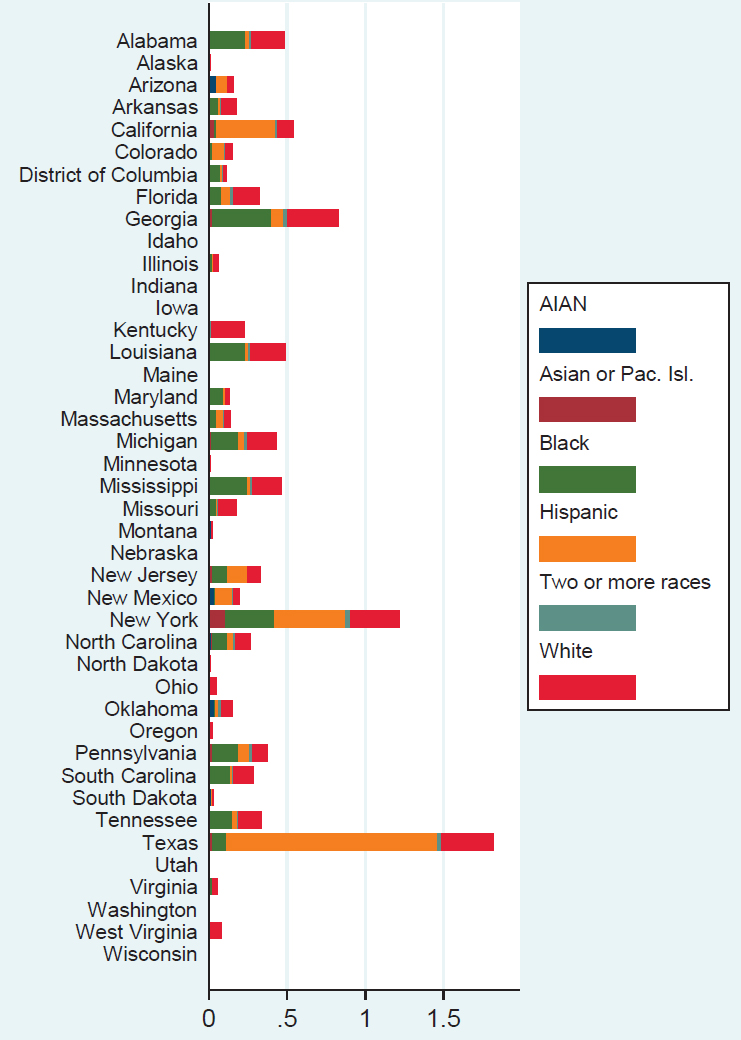

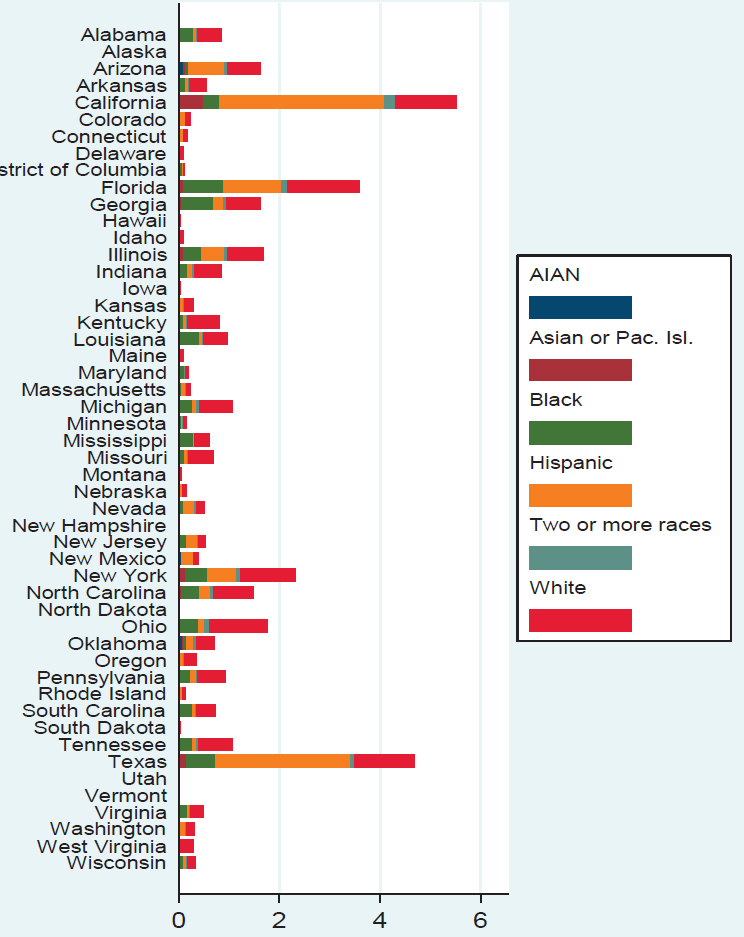

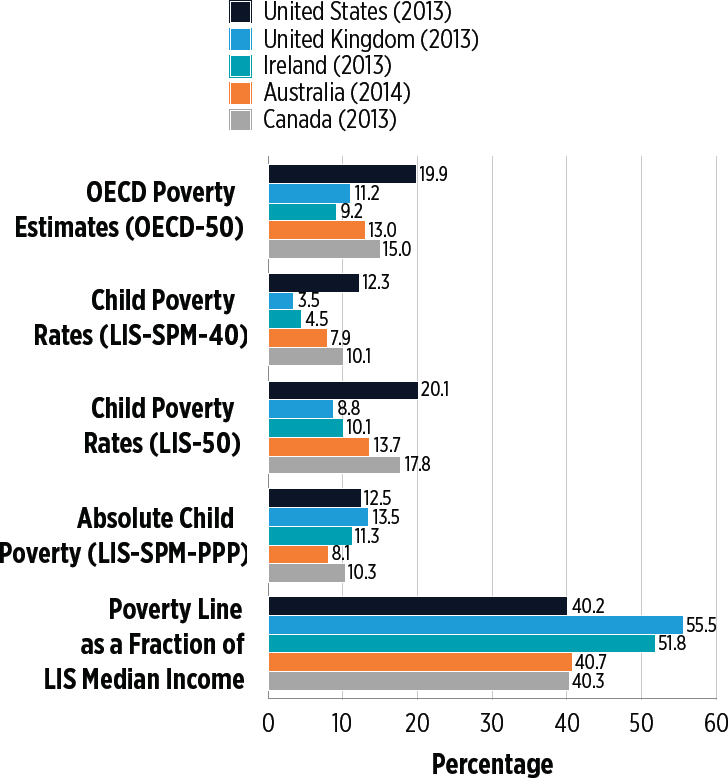

The impact on poverty threshold levels of including regional COLAs—whether based only on housing costs or on consumption items more broadly—turns out to be quite significant in terms of the resulting distribution of the population on either side of the line. It follows that incorporating geographic variation into poverty guidelines used in determining eligibility for public-benefits programs would have a considerable impact on the number of families eligible in different parts of the country (the overall number eligible nationwide might not vary much, if at all).26 In high-cost areas, such as the urban areas of the East and West coasts, COLAs increase the size of the population falling below the poverty line, both in absolute terms and proportionally. Meanwhile, in lower-cost regions, such as states in the South and Midwest, the portion of the population falling below the poverty line decreases (Curran et al., 2008). For example, based on Census Bureau data for 2015–2017, Mississippi’s official poverty rate for the total population of 19.5 percent was more than 3 percentage points higher than the cost-of-living adjusted SPM for the same period. In California, during the same period, the SPM rate was 5.6 percentage points higher than the OPM rate, and at 19 percent was the second-highest rate in the nation (Fox, 2018).

___________________

25 Thresholds are adjusted to reflect family size and composition. See App. D, 2-4 for a full discussion of equivalence scales.

26 Poverty guidelines are a version of the official poverty thresholds that use a simpler method for adjusting for family size. They are developed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services for use in determining program eligibility (e.g., for SNAP)—see https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines.

Alternative Approaches to Geographic COLAs

An alternative geographic COLA approach, explored in Renwick et al. (2014), involves applying state and metropolitan regional price parities (RPPs), which account for cross-area variation in a broader set of essential consumption items rather than simply housing costs. This method may draw from either an “all item” index that tracks prices from a broad group of expenditure classes, or from an index focused on food, clothing, and rents. The Bureau of Economic Analysis has been measuring variation in living costs through its RPP program for several years (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2017). Its estimates (which combine CPI data for various consumption expenditure classes, including rents, food, apparel, transportation, housing, education, recreation, medical, and other goods and services) can be used to express price levels for states and metropolitan areas in comparison to the overall national averages. Using the RPPs produced by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the Tax Foundation (2017) demonstrated that, relative to what can be purchased at the national level for $100, a market basket can be purchased worth $116.01 in Mississippi, worth $115.21 in Alabama, and worth $114.42 in Arkansas. At the other end of the spectrum, $100 is effectively worth only $84.18 in Hawaii, $85.47 in the District of Columbia, and $86.73 in New York State.

Renwick et al. (2014, p. 2) found significant differences between poverty thresholds adjusted by the rent index only and those adjusted by an all-item RPP, “resulting in higher poverty rates for 15 states and lower rates for 26 states.” Even when the narrower (food, clothing, and rent) RPP COLA was used, poverty estimates were “higher than the median rent index poverty rates in 20 states, lower in 22 states and not statistically different in 9 states.” In metropolitan areas, use of the RPP lowers the poverty rates when compared to the median rent index, because percentage differences in the combined price level of goods and services are generally not as large as those for rents alone.

Both the 1995 National Research Council report on measuring poverty27 and a report by an Interagency Technical Working Group (2010) concluded that although adjusting the entire market basket may be desirable for an SPM, data on price differences for elements other than rent and utilities were inadequate to do so. However, given the subsequent work on RPPs by the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s Regional Price Branch, the situation has changed such that a COLA could be implemented.

___________________

27Measuring Poverty: A New Approach. Available at: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/4759/measuring-poverty-a-new-approach.

The Role of COLAs in Setting Benefits

Just as it makes sense to adjust poverty income/resource thresholds to reflect regional variation in the cost of achieving a given standard of living, it is also reasonable to consider treating benefit payment formulas similarly. Currently, most anti-poverty programs do not feature COLAs that would formulate variations in payment levels across regions. The CTC and the EITC are examples of programs that fall into this category, making them much more valuable in lower-cost areas (Fitzpatrick and Thompson, 2010).

Likewise, eligibility for SNAP, administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, is determined by a uniform national standard with maximum benefit allotments, deductions, and income eligibility standards (by family size) adjusted for price inflation over time (COLAs take effect on October 1 each year). With only a couple of exceptions, however, SNAP benefits to low-income families are not distributed according to the cost of living in a city or metropolitan area (USDA, 2013). Net monthly income (eligibility) limits, set at 100 percent of the poverty level for the household size, are different (higher) only for Alaska and Hawaii, and maximum benefit amounts only vary for Alaska, Hawaii, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.28

Regional COLAs for food have less impact than COLAs for housing, because grocery costs vary by region considerably less than rental costs do. For example, the Council for Community and Economic Research survey estimates that average housing costs in Tulsa are only 66 percent of the national average, while in Baltimore and San Francisco they are 155 percent and 295 percent, respectively. But even in the case of food, there are some extreme differences. In Manhattan, for example, costs are 158 percent of the national average, while food costs in Tulsa are 81 percent of the national average (USDA, 2013). In either expenditure category, however, measured child poverty rates would be increased (relative to the OPM) in places like New York and California by including COLA adjustments to offset high housing or food costs.

APPENDIX D, 2-6

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE RESOURCE MEASURES USED BY THE OPM AND SPM POVERTY MEASURES

As noted in the text (see also Appendix D, 2-2), family resources in both the OPM and SPM poverty measures are the sum of money income from all sources, including earnings and government cash benefits such as Social Security and Unemployment Compensation. A key difference

___________________

28 Families with housing and utility costs that exceed one-half of net income are allowed a deduction for excess shelter costs, which may be more likely to occur in areas with higher-than-average housing costs generally.

between the OPM and SPM resource definitions is that SPM-based family resources also include “near-cash” income benefits such as SNAP (formerly known as food stamps) and housing subsidies, as well as near-cash benefits from many smaller programs. The SPM resource measure is also an after-tax measure, including deductions for payroll and federal and state income taxes as well as additions to resources through the EITC and the CTC. Table D2-4 provides a more complete accounting for the differences between OPM resources and SPM resources.

APPENDIX D, 2-7

POVERTY AMONG AMERICAN INDIAN AND ALASKA NATIVE CHILDREN

American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIAN) make up a small but rapidly expanding proportion of the U.S. population (Norris, Vines, and Hoeffel, 2012).29 Of the 5.3 million people who identify as AIAN, nearly one-half also identify as some other race, and the mixed-race population is growing faster than the AIAN-alone group (Norris, Vines, and Hoeffel, 2012). Because of the AIAN population’s relatively small size, data documenting it are scarce, particularly concerning AIAN children. In this appendix, we draw upon data from large-scale data collections efforts conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Unlike other minority groups in the United States, the AIAN population is also recognized as a political group, with political rights that may or may not align with racial or ethnic designations. As such, the AIAN population is eligible for certain programs and benefits that would otherwise be deemed illegal or unconstitutional in other settings (e.g., preferential hiring, treaty payments, and sovereign immunity). These benefits accrue directly as a result of their unique political status and not from a racial or ethnic designation. In the discussion that follows, we will primarily discuss the AIAN population as a racial and ethnic group; in Chapter 7, we discuss potential programs that may be of benefit only to the AIAN population that are considered citizens of their tribal nations.

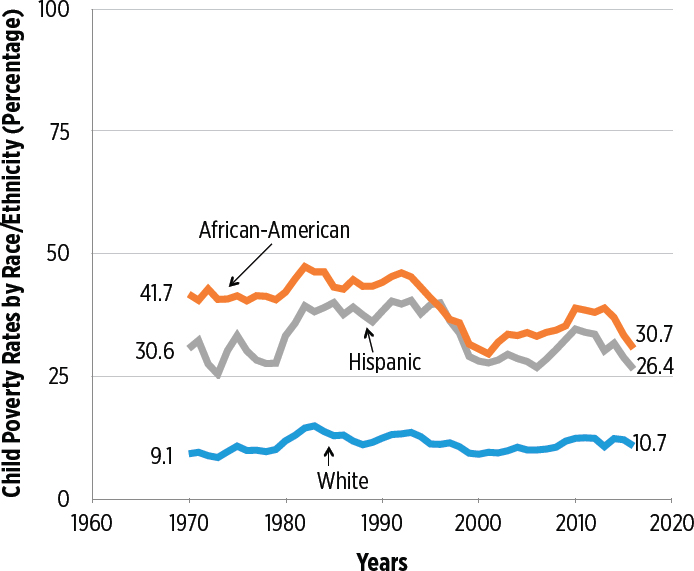

As measured by the OPM,30 the child poverty rate among the AIAN population as a whole was 31 percent in 2015, but there are differences by race and geography (Table D2-5). The OPM poverty rate for the entire population identifying as at least part AIAN increased from 27 to 31 percent from 1990 to 2016. However, for the AIAN-alone child population,

___________________

29 This appendix is adapted from a study (Akee and Simeonova, 2017) commissioned by the committee for this report.

30 Poverty data measured by the Supplemental Poverty Measure for this population were not available for all time periods covered in this analysis.

TABLE D2-4 Difference Between OPM Resources and SPM Resources

| Resource | Measures | Market Income Poverty | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OPM | SPM | ||

| Market Income | |||

| Wages and Salaries | X | X | X |

| Self-Employment Income | X | X | X |

| Farm Income | X | X | X |

| Returns from Assets | X | X | X |

| Child Support and Alimony | X | X | X |

| Private Disability and Retirement | X | X | X |

| Transfers | |||

| AFDC/TANF | X | X | |

| Social Security Ret./SSDI | X | X | |

| SSI | X | X | |

| Unemployment Insurance | X | X | |

| Food Stamps | X | ||

| Free/Reduced Lunch | X | ||

| Housing Subsidies | X | ||

| LIHEAP | X | ||

| Veterans Payments, Workers Comp | X | X | |

| Taxes | |||

| EITC | X | ||

| Child Tax Credit | X | ||

| Additional Child Tax Credit | X | ||

| Stimulus Tax Credits/Rebates | X | ||

| Federal Taxes, Other | X | ||

| State Taxes | X | ||

| Payroll Contributions to Social Security and Medicare | X | ||

| Deductions | |||

| Child Support | X | ||

| Medical Out-of-Pocket Expenditures | X | ||

| Other Work Expenses | X | ||

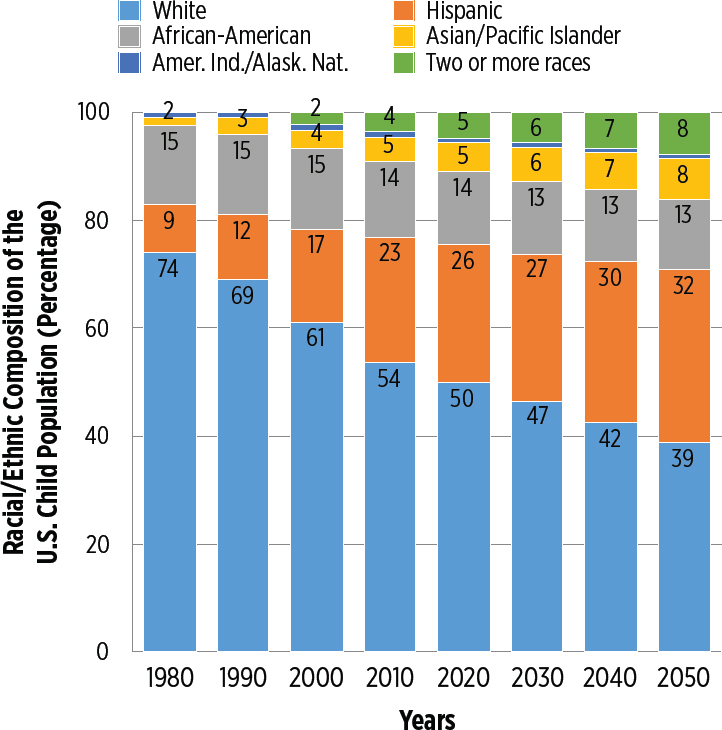

| Child Care | X | ||