5

The Growing Complexity of Farm Business Structure: Implications for Data Collection

A better data collection strategy is needed to improve the measurement of complex farm operations, and that is what we seek to present in this chapter. Particular attention is given to the Census of Agriculture and Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS), for which a critical aspect of data collection is construction of the sampling frames used to enumerate and survey farm entities at appropriate levels of disaggregation.

Defining the population of productive or income-producing units is a prerequisite to frame construction. Depending on the purpose of the survey instrument, the relevant population may be businesses, land units, or households. The presence of large complex farm operations creates challenges to defining statistical units for observation and reporting, challenges that do not exist to the same extent in the case of simple farms. The operator dominant methodology currently used in many U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) surveys and the operation dominant methodology used in the Census of Agriculture are compared here with alternative methods for organizing the reporting of farm production and finances.

A second issue addressed in this chapter is the relationship between data collection approaches and potential respondent burden, with the goal of improving both survey response rates and data accuracy. Several actions are recommended to reduce respondent burden, including strategic use of administrative and other nonsurvey data sources. Because USDA currently exploits nonsurvey data sources for other reporting efforts, it is a natural extension to treat complex farm operations within the context of an integrated system of data collection. In fact, doing so would be consistent with efforts across the federal statistical system to increase reporting capacity by

exploiting linkages across survey, administrative, and private-sector data collection programs.

5.1. DEFINING THE STATISTICAL UNITS OF FARM, FARMER, AND LAND

A statistical unit is an identifiable element or group of elements that may be selected from a frame when drawing a sample for a survey or census. For a business list frame, the statistical unit is the operation or the operator, recorded in the sampling frame by their name or ID (or both). For an area frame, the statistical unit could be a segment, a tract, or a field. When considering the appropriate statistical unit for measuring complex farm operations, the motivating question should be “what do we want to measure?” At least conceptually, there are three types of statistical units that can come into play, each with a distinct emphasis:

- the farm operation: institutional unit (later in this chapter redefined as statistical enterprise/establishment)

- the people: individuals and households

- the land: farmland, subdivided into fields

As documented in Table 5.1, each type of statistical unit embodies different attributes. Key variables may be best collected using statistical units that are not necessarily the same across different situations. All of these units, however, should in principle be capable of being linked to one another and, in some cases, to additional information. The variables that can be collected from each type of statistical unit can overlap in some cases, such as for land use and production information, but in many other cases the variables are unique and refer only to that particular type of unit.

Linkages exist between each of these statistical units. For example, ownership, decision making, or employment linkages exist between the business unit and the individuals and household involved, and a geospatial link exists between the business unit and the land. Designing sample frames that maintain reliable linkages between statistical units should be a high priority in a data collection program, because such linkages can be used to indirectly generate representative samples of statistical units across different frames. Using these linkages can allow one to overcome the challenges in creating a complete frame for a single unit-type, which otherwise can be prohibitively expensive or simply infeasible. For instance, a probability sample of farms can be used to define an induced probability sample of households, with its probabilities determined by applying indirect sampling principles (Lavallée, 2007).

TABLE 5.1 Statistical Sampling Units in Agriculture and Their Attributes

| Institutional Unit of Farm (enterprise/establishment) | Individuals and Households | Land | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture Nomenclature |

|

|

|

| Attributes |

|

|

|

| Key Variables |

|

|

|

| Potential Sampling Frames |

|

|

|

| Linkages to Other Statistical Units |

|

|

|

As farms become increasingly complex, the traditional perception of farms as self-contained, family-operated businesses no longer accurately captures the contemporary institutional units responsible for the majority of agricultural production in the United States. The statistical and policy-making communities are better served by recognizing that while there is a set of attributes that can be applied to the business part of the operation, there is also a nonoverlapping set of attributes that belong to the operators of those businesses. The remainder of this section examines in greater detail delineations between these different types of statistical units.

Applying alternative definitions of farm (an income-generating institutional unit), farmers (the individuals and households connected to the ownership and operation of farms), and farmland (the locations where production activities occur) may lead to changes in the conclusions reached about important contemporary agricultural policy issues. For instance, an alternative definition of farmland could encompass urban farms. Clearer alternative definitions should also yield more informative answers. Moreover, comparing how these answers change depending on the definition employed is itself an informative exercise.

Some of the challenges currently encountered by USDA exist because of the amorphous statistical unit that arises (in part) by allowing farmers to define the farm and its boundaries. When farms are complex—so that there is no longer perfect overlap between the institutional unit, the household, and the location—this ambiguity makes it difficult for the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) and Economic Research Service (ERS) to accomplish their missions of providing policy makers, researchers, and producers with reliable estimates of agricultural production activity. For this reason, as discussed below, more structure should be imposed on respondents regarding the definition of their farms and operations (two terms that are replaced in later sections with enterprise and establishment).

To provide this definitional structure, one should build on three broad principles: (i) definitional clarity; (ii) recognition of the sampling unit that is best suited to provide particular information; and, as explained above, (iii) continuing maintenance of a “crosswalk” that links each type of sampling unit with the others. These principles, summarized by example in Table 5.1, are briefly explained next.

The Farm as an Institutional Unit

Farms may be classified by their primary and secondary industries, using the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). The farm activities themselves (and the resultant output) can also be classified, using the North American Product Classification System (NAPCS). Although a farm will typically be classified under one primary industry,

such as crop production, it may also be involved in other productive activities—including those classified as agricultural production, such as cattle ranching, or outside agriculture, such as local trucking—that are not in that industry.1 Other attributes of the farm include its ownership, legal structure, farm typology, and geographic location.

As institutional units, farms are best equipped to answer questions related to the operation of the farm, including its finances, management practices, input usage, and output.

Individuals and Households

A key part of USDA’s mission is to provide information regarding the well-being of households involved in operating farms (as discussed in Chapter 2). However, individuals have different attributes from the farms they manage, and the type of information that can be obtained from individuals, as statistical units, is different from what can be collected from a farm as an institutional unit.

The link of an individual to a farm varies from case to case. Different individuals may be involved in different day-to-day decisions regarding the operation. Individuals can be categorized by age, education, and years of experience, and their relationship with the farm may be one of ownership, decision making, work as a paid manager, or as some other type of employee. Moreover, an individual may engage in both on-farm and off-farm business activities.

The key variables that can be collected from individuals or households include on-farm and off-farm income, assets, and debt. Households may also have on-farm and off-farm employment.

Land

Production activity can be tracked for the whole farm, but it can also be tracked by geographical location. A farm’s land can be broken down into segments, tracts, and fields; the latter is the smallest meaningful unit of disaggregation for which information can be reported, for example on the commodity grown, fertilizer applied, or irrigation used.2

___________________

1 One outcome of the classification system is that some of the largest complex farms, in fruit and vegetable agriculture for example, are not listed as farmers; Dole Food Company falls under NAICS 424480 (fresh fruit and vegetable merchant wholesalers) and Premier Raspberries LLC under NAICS 424410 (general line grocery merchant wholesalers). These firms hire farm workers and have contracts with farm worker unions.

2 As noted in Chapter 2, a field is defined as a continuous area of land devoted to one crop or land use (according to the ARMS Phase II manual). In the June Area Survey, the one-mile-by-one-mile segment is subdivided into tracts (a portion of the farm that is located in the sampled

Attributes of a plot of land include physical location, soil and climate, and water and land use, as well as the commodity produced. In addition to production information, other information that can be collected from a plot of land includes ownership and tenure (if rented), size (acres), and use.

In complex farm operations, the linkages between the farm, the individuals and households involved, and the land are more difficult to track. Understanding these linkages is important for the USDA to deliver on its information commitments (as identified in Chapter 2).

5.2. AREA SAMPLING FRAME METHODS USED BY THE USDA’S RESEARCH, EDUCATION, AND ECONOMICS (REE) MISSION AREA

The USDA/REE has a well-established sampling frame methodology. By using a combined frame of farm businesses and individuals, NASS and ERS track the linkages between individuals and farms. This structure works well for simple farms, but measurement issues arise as operation complexity increases. In this section, the current USDA/REE approach is described and some of its limitations are presented.

NASS List Frame

NASS uses a dual sampling frame approach for most large-scale national surveys and the Census of Agriculture. It uses the list frame, which includes names for both persons and operations, to identify, stratify, and sample operators and operations of interest.

NASS maintains the Enhanced List Maintenance Operations relational database, which includes tables organized by person, by operation, and by person operation. Every record in the database is associated with at least one row or entry from each of these three tables, where a PID (person ID) uniquely identifies a person, OID (operation ID) uniquely identifies an operation, and POID (person-operation ID) is a unique combination of person and operation. For example, an operation (OID) can be associated with multiple persons (PIDs), leading to several person-operation pairs (POIDs). All of these IDs are used to select the statistical units for the NASS surveys and the Census of Agriculture. NASS uses both operator-dominant and operation-dominant statistical units, depending on the survey. Operator-dominant statistical units are operators reporting for all their operations, and this is used for all multiple frame surveys like ARMS. On the other hand, operation-dominant statistical units are based on operations,

___________________

segment, so equal to or less than the full farm acres), with only one tract per farm, and then into fields. The June Area Survey Data Manual provides additional details on these definitions.

rather than individuals, and are used for the Census of Agriculture and the majority of surveys conducted by NASS.3

As a result of this structure, a “person” has two roles in the statistical framework. The first role is as a contact for the operation. The second role is as a statistical unit in their own right. The first role makes sense for supporting a list of farms, but the second role is likely not the optimal approach to use when seeking to obtain a sample of households.4

Currently, the list frame is maintained mostly at NASS headquarters, where sample selection is also undertaken. Surveys are typically conducted by the NASS state and regional offices, whose staff modify list frame information based on feedback received from those surveys. Regional field offices are responsible for procuring new list sources and are involved daily in reviewing and updating their list frames. Recognizing that this allocation of responsibilities could create disconnects in sharing and updating list frame information, in 2012 NASS created the Frames Maintenance Group in St. Louis to better centralize maintenance of the list frame. This has led to more consistency and efficiency in the frame’s maintenance.

More broadly, there are a range of ways in which NASS’s list frame information can be updated: (i) through the Census of Agriculture, as a complete enumeration; (ii) using data from other surveys; and (iii) based on administrative records. NASS is well-equipped to systematically handle the first two sources. Ideally, as detailed in Chapter 6, NASS would have access to a broader set of administrative data, such as tax information, information collected for income-support programs administered elsewhere in USDA, and information from other federal statistical agencies.

Area Frame

The NASS area frame is intended to be an exhaustive collection of land use segments. Unlike the list frame, the area frame is, in principle, complete with respect to coverage of the population of farms. However, it is inefficient and expensive to maintain and to enumerate. It is difficult to link a specific plot of land to a farm or farm household through farm operators. One of the main purposes of the area frame has been to provide a way to estimate the undercoverage of the list frame through selecting and enumerating a sample of the land segments, matching the operations on the

___________________

3 Special codes simplify overlap by maintaining target name and operator dominant classification for individual/partnership, secondary decision maker, decision maker for multiple operations, and large/complex farms.

4 ARMS is the primary example of when the agency focuses on households. This approach may be efficient for multiple frame surveys, and for ease of “overlapping” the Area Frame to the List Frame for measuring list incompleteness. It should again be noted that the number of entities with “multiple” operations on the list frame is a very small percentage.

area frame sample to the list frame and determining those area frame farm operations not on the list. This information is used to create dual-frame estimates for planted acres and agricultural production in NASS surveys and capture-recapture estimates for the Census of Agriculture. To make these estimates, independence between the list and area frames is a necessary assumption.

Linkages Among Farms, Individuals, and Households

The sampling frame for farm households in ARMS is the household attached to the principal operator, defined as the person most responsible for making decisions about the farm operation. The current ERS approach is to use the ARMS sampling weights to expand to the population of farm households from the sample of principal operator households. Even though it is not explicitly treated as such, this is an application of indirect sampling: using a sample of farm operators with known probabilities, the connected principal operators are surveyed and the sampling weights are “inherited” from the farm operator sample. However, because the current sampling frame consists of pairs of farm operators and operations, the implied population of farm operators that can be reached through this approach will not always correspond to the true target population of “farm households.”

Additionally, the current sampling approach may not always capture the right target population, because operators with multiple operations have a higher probability of being sampled than do operators with a single operation. For example, a person’s household with two farms is twice as likely to appear in the sample as another person’s household that only operates a simple business consisting of one farm, but the weights will be the same, assuming that the farms are otherwise identical. These issues can be remedied within the same sampling framework by developing a more detailed set of linkages between the operator or household and the operation units, as will be further described below.

The mismatch between the actual farm household population and the population reachable through the current operator-dominant approach has a number of notable disadvantages, which have already been identified by data users. Currently, information is collected only on the household of the principal operator. If such a designated operator discontinues being involved with an operation from one period to the next, the continuity of information for households associated with the operation may not be preserved.

In addition, the current approach focuses on the principal operator. When constructing statistics derived from these data, a bias is created whereby women and younger generations are underrepresented; principal operators are also older and their households are richer than those of

nonprincipal households. The same information is collected regarding the operator and spouse, so this bias occurs in reporting, not in data collection (that is, ERS only reports on the characteristics of the principal operator).

5.3. ALTERNATIVE MODELS AND METHODS FOR DESCRIBING FARM PRODUCTION AND FINANCES

The challenge of accurately reporting economic activity within complex business structures is not unique to the American agricultural sector. Other statistical agencies, both domestically and internationally, are faced with the challenge of creating organizational systems that can accommodate complex business structures. In doing so, they must balance the need to create a complete, unduplicated list frame of all organizational entities in the population against the ability of respondents to see themselves represented within the statistical structure provided. The following is a review of current practices adopted by international and domestic statistical agencies to accommodate complex organizational structures, designed to lead to more specific recommendations for the U.S. farm sector.

International Guidance on Registers

The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) has published the Guidelines on Statistical Business Registers (henceforth referred to as the Guidelines) with the aim of advising member countries on creating and implementing a standardized approach to the treatment of registers of business enterprises. The Guidelines call for the inclusion of all institutional units engaged in productive activities.5 These include government units, business corporations, and nonprofit institutions. The Guidelines also suggest including household enterprises (both employers and nonemployers) in statistical business registers if suitable administrative sources are available to do so (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 2015, pp. 27–28).

In addition, the Guidelines makes recommendations for a “statistical unit model” that presents a hierarchical structure for representing the activities of institutional units. These units—enterprise group, enterprise, establishment, and local unit—are defined as follows:

- An enterprise group is a collection of enterprises linked by ownership or control.

___________________

5 Statistical units are similarly defined in the System of National Accounts, 2008 (2008 SNA) and the International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities, revision 4 (ISIC Rev.4).

- An enterprise is “the level of the statistical unit at which all transactions, including financial and balance sheet accounts, are maintained, and from which international transactions, an international investment position (when applicable), consolidated financial position and net worth can be derived.” (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 2011, pp. 40–41). An enterprise may be composed of multiple legal entities.

- An establishment is a part of an enterprise in which a single productive activity occurs, or in which the primary activity accounts for most of the value added of the entity. The statistical unit, at this level, must be able to provide data on production, intermediate consumption, investment (that is, capital expenditures), and employment. An establishment may incorporate a geographic component, such as physical location, as well as a kind-of-activity dimension.

- A local unit (location) is a statistical unit in which an activity occurs. If it exists only as a cost or revenue center it is part of an establishment.

The Guidelines recommend that statistical business registers track the linkages among these units. Maintaining linkages between the enterprise group, enterprise, and establishment is important as it provides a connection between the location of the activity (establishment) and the legal structure of the entity (enterprise), which further downstream will permit the integration of data, including the potential use of administrative data.

It is important to note that the generic nomenclature covering the statistical treatment of business structures is not necessarily the same as commonly held terminology in the agricultural sector. For instance, usage of the term “enterprise” in a business register is different from the agricultural industry’s usage of the term, where it denotes the activity that can occur within a farm, as in the case of a crop or livestock enterprise within a farm.

In this section, descriptions of practices by the Census Bureau, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), and international bodies follow their naming conventions. Recommendations for USDA will use slightly different terminology in order to reduce confusion with agricultural industry norms. Specifically, a farm establishment is a business establishment that is engaged in farming. A farm business is a collection of business establishments linked by ownership or control that has at least one farm, and corresponds to an “enterprise” in statistical usage.

RECOMMENDATION 5.1: The U.S. Department of Agriculture should consider adopting definitions of (1) farm establishment as a business establishment engaged in farming and (2) farm business as a

collection of business establishments with at least one farm establishment linked by common ownership or control.

The Guidelines include recommendations specifically directed at the agricultural sector. One recommendation is that agricultural production be included in statistical business registers. There is a recognition that some countries may organize separate farm registers, as is current practice in the United States. However, the Guidelines raise a concern about maintaining a farm register distinct from a statistical register of nonfarm entities, because doing so can make it difficult to maintain consistency of coverage across different economic surveys (p. 29).

The Guidelines also recognize that a farm does not always correspond to an enterprise. A farm may occur within a complex legal entity that could include other activities. Similarly, a farm may involve more than one legal entity. Finally, it is recommended that agricultural household (i.e., unincorporated) enterprises be included in statistical business registers, if an administrative source can be found to identify them.

UN FAO World Program of the Census of Agriculture 2020

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations provides guidance and support to countries undertaking agricultural censuses in the FAO World Program of the Census of Agriculture 2020 (hereafter referred to as WPCA 2020). Here, the recommended statistical unit is the agricultural holding, defined as a unit engaged in agricultural production under single management.6 This is very similar to the way USDA defines a farm (see Chapter 2).

This standard splits agricultural holdings into those that are in the household sector (owned by household members) and nonhousehold holdings (owned by corporations or government institutions).7 In the case of nonhousehold agricultural holdings, the establishment, as defined earlier, is recommended as the unit of measure. In the case of households, the house-

___________________

6 More specifically, the WPCA 2020 defines an agricultural holding this way: “An economic unit of agricultural production under single management comprising of all livestock kept and all land used wholly or partly for agricultural production purposes, without regard to title, legal form or size. Single management may be exercised by individual or household, jointly by two or more individuals or households, by a clan or tribe, or by a juridical person such as a corporation, cooperative or government agency. The holding’s land may consist of one or more parcels, be located in one or more separate areas or in one or more territorial or administrative divisions, providing the parcels share the same production means, such as labor, farm buildings, machinery or draught animals” (p. 43).

7 A household is an individual person, or a group of individuals that live together for the common provision of food or other essentials.

hold itself is treated as an enterprise with only one agricultural production establishment.

Given that agricultural activity may be a secondary activity for some establishments, the units included in a census of agriculture should extend beyond establishments whose industrial classification is primary agriculture, meaning agriculture is the activity with the greatest value-added. In other words, to have a complete census of agriculture, even establishments for which farming is a secondary activity must be included. When creating a farm register, WPCA 2020 suggests, ideally one should ensure that it (i) contains information about the unit (land, types of livestock, crops, etc.); (ii) avoids duplications and omissions; and (iii) is regularly updated.

Treatment of Business Lists in the U.S. Federal Statistical System

Two federal statistical agencies, the Census Bureau within the Department of Commerce and the BLS within the Department of Labor, maintain distinct business registers using different administrative data sources. Each is described in detail below.

The Census Bureau

The Census Bureau maintains the Business Register, a relational database that links data from administrative sources and survey products.8 As with NASS farm list frames, the Business Register combines data from multiple sources “with the goal of providing comprehensive, accurate, and timely coverage of business units” (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018, p. 34). The statistical structure of the Business Register follows the enterprise-establishment model, which is similar to UNECE’s Guidelines. The establishment is the economic unit that is usually a physical location where activity occurs. It is seen as the smallest, most discrete business unit. A firm is a collection of establishments linked by ownership or control; it consists of a top parent company and all of its constituent establishments. As in the case of a simple farm, for a single-establishment business the firm (or enterprise) and the establishment units are the same. Larger firms, on the other hand, may consist of hundreds or thousands of establishments (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018).

As the smallest business unit, each establishment in the Business Register requires a unique survey unit identifier. The primary data sources for

___________________

8 For detailed information on the Business Register, see https://www.census.gov/econ/overview/mu0600.html, and https://unstats.un.org/unsd/trade/events/2015/aguascalientes/10.Panel%20III%20-%20Presentation%202%20-%20US%20Census%20Bureau.pdf.

constructing survey unit identifiers are income and payroll tax filings that the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) shares with the Census Bureau in accordance with Titles 13 and 26 of the U.S. Code. Thus, the Census Bureau faces the following challenge: It must use the tax-reporting behavior of businesses to identify economic activity and then organize that activity within the establishment-enterprise hierarchy.

Within the Business Register, there are four exhaustive and mutually exclusive categories of establishments: (i) nonemployer sole proprietorships, (ii) nonemployer establishments not organized as sole proprietorships, (iii) employer establishments in single-establishment (single unit) firms, and (iv) employer establishments in multi-establishment (multi-unit) firms. For the first three categories, the administrative data provided by the IRS is sufficient for constructing a unique survey unit identifier. For the establishments in multi-unit firms, however, the task is more complicated. Indeed, to maintain the establishment-enterprise hierarchy, the Census Bureau must impose a reporting structure on respondents. For this reason, a somewhat detailed description of the process is instructive.

For nonemployer establishments organized as sole proprietorships, the survey unit identifier can be constructed as a unique transformation of the Social Security Number (SSN) of the proprietor, as reported on IRS Schedule C: Profit or Loss from Business.9 While one individual may operate multiple sole proprietorships, if the business activity taking place in one proprietorship is unrelated to the business activity at another proprietorship the individual must file a separate Schedule C for each. Thus, the construction of unique identifiers for each establishment is quite straightforward, even when multiple establishments share the same SSN.

For all other establishments, the Employer Identification Number (EIN) serves as the tax identification number. Thus, partnerships, corporations, and cooperatives that do not hire employees can each be uniquely identified by the EIN used on their income tax form.10 In other words, for nonemployers that are not sole proprietorships, the establishment and the (income) tax-reporting entity are the same. As a result, any one-to-one mapping from EIN to survey unit identifier will suffice.

A similar situation presents itself for single-unit employers, although the source of federal tax data is different. Regardless of the legal form of organization, employers must report income, social security, and Medicare

___________________

9 Although sole proprietorships that pay excise taxes or operate a Keogh retirement plan must apply for an EIN from the IRS, it is not reported on IRS Form 1040, Schedule C.

10 Partnerships report income on IRS Form 1065; C-Corporations report income on IRS Form 1120; S-Corporations report income on IRS Form 1120-S; Cooperatives and Associations report income on IRS Form 1120-C.

tax withholding for all eligible workers11 using their EIN as a unique tax identification number. Again, the establishment and the (payroll) tax-reporting entity are the same, so the survey unit identifier is easily constructed as a transformation of the EIN.

The SSN and the EIN were created to serve administrative purposes, namely the collection of taxes and the crediting of wage earnings. For nonemployer establishments and employer establishments in single-establishment firms, there is an almost one-to-one correspondence between the tax entity and the business entity.

The one-to-one correspondence can break down, however, when a firm reports payroll information covering multiple establishments on one IRS payroll tax form, so that one EIN is associated with economic activity at more than one establishment. Administrative records by themselves are insufficient for maintaining the establishment-enterprise hierarchy in its Business Register.

For this reason, the Census Bureau supplements the administrative information provided by the IRS with responses to the Company Organization Survey. The purpose of the Company Organization Survey is to link business entities within organizational hierarchies through two simple questions: (i) Is the responding company owned or controlled by another company? and (ii) How many establishments were operated by the responding company? If the answer to the first question is affirmative, the company is asked to provide the EIN of the controlling entity. If the answer to the second question is more than one, the company is asked to provide the location, employment, and payroll information of each establishment.

Through the Company Organization Survey, the Census Bureau is able to maintain a register that applies a consistent establishment-enterprise hierarchy with sufficient information to link establishments to parent firms. The benefit of linkages between establishments and firms is two-fold. First, it allows a consistent definition of the survey unit within the Business Register. Second, it allows reporting and analysis at different organizational levels. For some purposes, establishment-level information may be the most pertinent, but for other purposes firm-level aggregates may be most useful (National Research Council, 2007).

Having reviewed how the Business Register is constructed from a combination of administrative and survey data, it becomes easier to recognize how its design enables the Census Bureau to maintain the structure of complex enterprises and provide links between a range of entities, including

___________________

11 This information is reported for nonagricultural work on either IRS Form 941 (quarterly) or IRS Form 944 (annually). Information for agricultural workers is reported on IRS Form 943 (annually).

- survey units,

- employer units,

- address units,

- SSN units, and

- EIN units.

The benefit of having consistent institutional definitions and linkages from establishments to parent firms comes with costs. Because the tax reporting behavior of businesses does not map cleanly onto the establishment-enterprise hierarchy that the Business Register seeks to represent, the Census Bureau must conduct follow-up surveys—and surveys are costly to administer. In addition, the survey instruments force respondents to report information about business activity according to the hierarchy chosen by the Census Bureau, not necessarily the form easiest for the business to provide. Recognizing these costs, it is worth noting two important aspects of the Company Organization Survey: It is short and its directions are clear.

In order to support statistical activities such as surveys and administrative data linkage, the Business Register should contain core information on the following:

- unique identifier for each unit,

- business name,

- address,

- operational structure (providing linkages between farm establishments,

- size and activity measures (important for stratification, exclusion of very small units, etc.):

- payroll and employment

- revenue

- assets and liabilities, and

- NAICS classification (important for tracking nonfarm establishments that are part of a farming enterprise).

Beyond these items, which are essential for maintaining a farm register used as the frame for survey sampling and for the Census of Agriculture mailing list, the following additional items should be added if feasible—legal structure, and tax status. The inclusion of this information allows the Census Bureau to tailor receipt of survey instruments in ways that minimize total respondent burden. For example, the Economic Census is not a true census because smaller establishments, defined as those below certain size thresholds, are only sampled. Moreover, the value of these thresholds varies by industry.

Finally, the Census Bureau regularly updates the information contained in its register. For single-establishment firms and EINs, this is a continuous

process as new information is shared from the IRS or data is processed from census survey products. For multi-establishment firms, updating occurs on an annual basis as the Company Organization Survey and Annual Industry Surveys are processed.

A recent Committee on National Statistics (CNSTAT) report on reengineering the Census Bureau’s annual economic surveys (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018) raises some issues concerning the Business Register that are also relevant for the NASS list frame or for a potential Farm Register (described later in this chapter). The report argues that the Census Bureau’s Business Register would be more useful as a sampling frame, for the annual economic surveys and other purposes, if it “included information about special reporting units that are used for one or another of the surveys” (p. 36). As with farming, large business enterprises in most sectors account for a large percentage of total employment and output, so accurately measuring their activity is especially important in the production of reliable statistics. With this concern in mind, the authors of the CNSTAT report (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018) offered the following recommendation:

The Census Bureau should establish a centralized and coordinated Account Manager Program [in which analysts are assigned responsibility for a specific set of enterprises] that serves as a single point of contact for the largest enterprises with respect to all Census Bureau economic and business data collections. Account managers should have as their primary responsibilities not only the population of the Business Register with up-to-date information about these companies, but also the coordination and facilitation of company responses to the Census Bureau’s economic surveys over the course of the year. (p. 41)

This guidance would be equally applicable to the maintenance of a Farm Register, as described later in this chapter.

In addition, the Census Bureau, through collaboration between external researchers and Census staff, has linked Business Registers across time into a Longitudinal Business Database and associated Business Dynamics Statistics.12 Refined intertemporal and firm-to-establishment linkages are the primary difference between these data and County Business Patterns.13 The USDA could benefit from a similar approach.

___________________

The Bureau of Labor Statistics

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) also maintains a continuously updated business register, but does so using an entirely different administrative data source. Rather than federal income and payroll tax information shared from the IRS, the BLS builds its register from information it receives from state unemployment insurance programs. Despite these differences, the actual structure of the register is remarkably similar, contains much of the same information, and faces the same problem of maintaining the establishment-enterprise hierarchy. Just as a firm may report payroll tax information to the IRS for multiple establishments under one EIN, firms may report unemployment insurance information to the relevant state agency for multiple establishments under one account number. The BLS has its own survey instrument to separately allocate firm-level aggregates to individual establishments, namely the Multiple Worksite Report.

One key difference between Census Bureau and BLS taxonomy is that the latter typically associates an establishment with one activity, generally in a single location. If there is more than one activity at the same location, the BLS creates two different establishments as long as payroll records can make that feasible.

Because the registers for the Census Bureau and BLS are based on different administrative programs, their coverage differs in sometimes important ways. Most obviously, establishments without employees do not participate in unemployment insurance programs. As a result, the BLS register does not include nonemployer establishments, while the Census Bureau register does. In addition, because the unemployment insurance participation threshold for employers of agricultural labor is higher than for employers of nonagricultural labor, the BLS register only captures about 50 percent of agricultural employment.

Options for the Farm Register

The existence of multifarm, multibusiness operations, along with the complexity of the management and decision-making structure of these businesses, as described in Chapter 3, require modifications to the current list-frame approach.

RECOMMENDATION 5.2: The National Agricultural Statistics Service should expand on its list frame to create a Farm Register that provides an ongoing enumeration of all farm establishments in the United States.

This Farm Register would be similar to the current NASS list frame, but it would focus on the enumeration of farms as establishments and their characteristics while maintaining links to the farm business (the statistical enterprise) that the establishments are part of. The register would be an “evergreen” product and would be regularly updated as new information becomes available. Survey-specific list-frames would be drawn from this Farm Register at a single point in time to support individual statistical programs, including the Census of Agriculture and ARMS. As additional information on farms is collected through ongoing activities, the Farm Register would be updated. However, a list-frame drawn from the Farm Register would be a stand-alone product over the course of the collection activity and would not be modified.

Given the existence of a one-to-many or many-to-many relationship between individuals or households and farms, the Farm Register could be structured as a set of relational databases that track the relationship between statistical structure, legal structure, and households.

RECOMMENDATION 5.3: The Farm Register should be consistent with other business registers in the federal statistical system. This register should maintain a linkage between statistical units, administrative units, reporting units, and household units.

The design of this Farm Register should be informed by the planned redesign of the Census Bureau’s Business Register.

Institutional Units

The Farm Register should follow an institutional unit (enterprise-establishment) structure similar to that of the Census Bureau’s Business Register, and unique IDs should be assigned to each of these units.

A farm establishment would be the smallest unit that could report agricultural production, including revenue, expenses, and employment. It would have an industrial classification, corresponding to its primary activity; however, secondary activities would also need to be identified. The Farm Register would need to pay closer attention to the household sector (as nonemployers) than the Census Bureau register does, given its importance to the agricultural sector.

A farm business, which would correspond to a statistical enterprise, would be a collection of farm establishments linked by ownership and control.

Table 5.2 summarizes the distinctions between administrative units, reporting units, and household units, which are described next.

TABLE 5.2 Relationships Among Statistical, Administrative, Reporting, and Household Units

| Description | Purpose | Linkage with Other Units | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Units | A prescribed consistent representation of the statistical structure of the farm (i.e., the enterprise-establishment structure used in the Census Bureau) | Provide a consistent and unduplicated representation of the structure of American farms. These are the sampling units for USDA surveys | See below |

| Administrative Units | Representation of the structure of the farm from the viewpoint of associated EIN (or SSN) accounts | Provide the capacity eventually to link administrative data to survey data, or to provide micro-level coherence with the Census Bureau or BLS | The top level of a farm business will have a corresponding set of EINs or SSNs (in the case of proprietorships) |

| Reporting Units | A group of statistical units that are combined or split to aid the respondent in reporting information | To aid respondents who may have difficulties, or face significant burden, in reporting for each statistical unit | Reporting units are linked to their constituent statistical units, so that reported data can be allocated to each |

| Household Units | Households associated with farm producers | Provide a link between the household and the farm business | Producers should be responsible for some aspect of decision making on the farm, so there should be an ownership or employment link with the statistical units |

NOTES: BLS = Bureau of Labor Statistics, EIN = Employer Identification Number, SSN = Social Security Number, USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Administrative Units

The administrative unit corresponds to EIN account(s) or the SSN account (in the case of a proprietorship) associated with the farm business. Acknowledging the current legislative and regulatory constraints that prevent the sharing of administrative data across agencies, if it became possible to share these data the Farm Register could then be used to facilitate data linkage. In this respect, it would be beneficial for the Farm Register to be designed to allow for the use of EIN and SSN units in a manner similar to how this is done at the Census Bureau.

Reporting Units

The reporting unit is the entity or element about which information is to be obtained (in contrast, the sampling unit is the person responding to a survey).

RECOMMENDATION 5.4: The National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) should be more prescriptive in the designation of statistical units but maintain the flexibility to collect from a reporting unit that best suits the respondent. It would be the responsibility of NASS to allocate the reported data back to the statistical unit.

Using the farm establishment or farm business, as defined above, may not be optimal (from the respondent’s perspective) for reporting survey or census data. Statistical units may be agglomerated or split into different reporting units to ease respondent burden, but the collected information will be allocated or agglomerated to correspond to the farm establishment or farm business, as more strictly defined.

Household Units

Given the requirement to produce statistics on the financial well-being of farm households, it is important to draw a link between the farm business structures and their operators. The Farm Register would contain information on the linkage between the statistical units (farms or individuals) and households (as described in section 5.3).

Because the current sampling frame creates considerable complexity when dealing with farm operations that are more complex than single-unit farm establishments, the proposed approach would simplify sampling by maintaining separate lists of farms, farm operators, and land holdings, such that a sample unit may be selected that is optimal for the measurement of that characteristic. For instance, information on off-farm income

is best obtained from a household-type survey rather than from a survey that targets farms.

RECOMMENDATION 5.5: All farm establishments in the Farm Register should be linked to a farm business. In most cases, farm businesses will include only one farm establishment, but they may include more than one.

The following information should be maintained in the Farm Register for each farm establishment:

- primary NAICS of the farm establishment,

- commodity output flags (NAPCS),

- name and address of farm,

- other geolocation indicator,

- size indicators (sales, number of employees), and

- linkage variables (e.g., EIN).

The purpose of the agriculture statistics programs in NASS and ERS is to cover all farm activity, regardless of the industry of the statistical unit. The farm register may therefore contain enterprises and establishments that do not have agriculture as a primary activity. If an enterprise is primarily engaged in processing farm products but also operates its own farms, although most of the value added could be associated with the processing and the enterprise is thus classified as manufacturing, the farming activity still needs to be captured. In order to maximize coherence across the federal statistical system, it would be ideal if a joint register could be developed with the Census Bureau.

Table 5.3 summarizes the differences in approach between the current statistical sampling frame for surveying farm businesses and the proposed sampling frame.

Sampling from the Farm Register

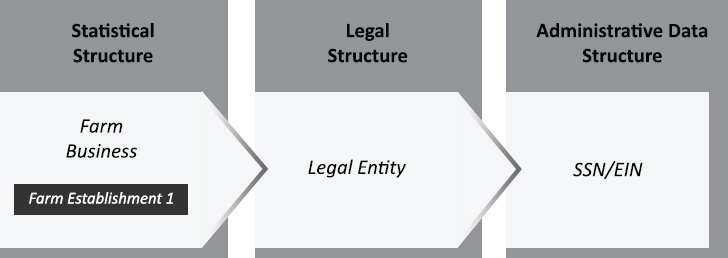

The proposed Farm Register differs from the current list-frame approach in that it provides a more prescribed structure for the collection of statistical units, while allowing for flexibility in combining units for reporting (collection entities) and eventual linkage to administrative data. Figure 5.1 demonstrates, in its simplest form, how these linkages would occur in the case of a farm business that controls a single farm establishment. This statistical structure is owned by a single legal entity and has an associated SSN (if a sole proprietorship) or EIN (if incorporated or an employer).

The statistical structure can be made more complex with the addition

TABLE 5.3 Differences Between Current and Proposed Approach for a Statistical Sampling Frame

| Current Approach | Proposed Approach |

|---|---|

Operation-Dominant

|

Institutional Unit (enterprise/establishment)

|

|

Operator-Dominant

Statistical units are identified by the “target name” for the farm or ranch—usually a person’s name

|

Household Unit

|

Area Frame

|

Land/Location

|

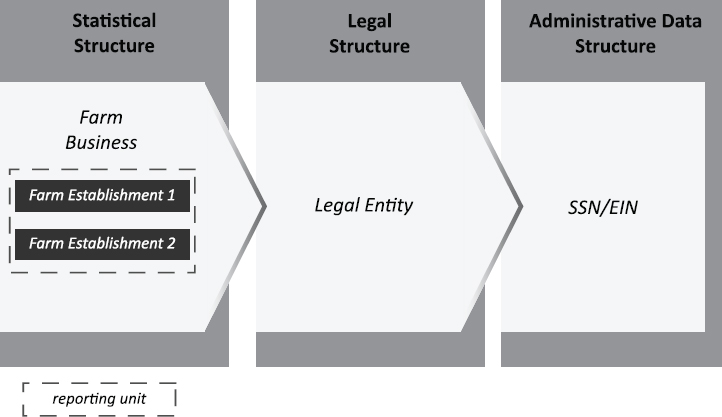

of multiple farm establishments to the farm business. This is depicted in Figure 5.2. In the more complex structure illustrated in Figure 5.2, the farm business organizes the farms as two separate profit centers, and each entity that is capable of reporting an economic surplus is identified as a separate farm establishment. If it eases reporting for respondents, these farm establishments could be combined, only for the purposes of reporting, into different reporting units or collection entities; however, reported data would still be allocated to each individual farm establishment.

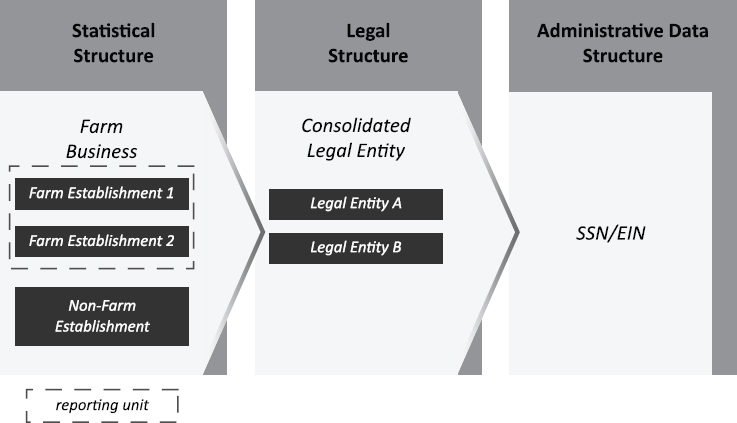

There may be added complexity if a farm business is engaged in both farm and nonfarm activity. If the nonfarm activity, such as value-added activities like trucking, keeps a separate set of books, then a separate nonfarm establishment should be created in the Farm Register. The farm

NOTE: EIN = Employer Identification Number, SSN = Social Security Number.

NOTE: EIN = Employer Identification Number, SSN = Social Security Number.

business may also create a separate legal entity. The legal entities may or may not correspond to individual establishments or farms, but the consolidation of the legal entities should be the same as for the farm business (see Figure 5.3).

In this last instance, all of the activities of the farm business should be captured in the Farm Register. This is important if there is to be eventual use of additional administrative records, which may be collected on a legal entity basis but would then need to be allocated within a complex statistical structure.

Treatment of Households and Individuals

The USDA already tracks some people associated with farm operations, such as those involved with decision making, employment, ownership, and contacts for surveys. However, this is not done systematically, so there is a lack of coherence about who can be linked. The aim in the past has been to identify a principal operator among all persons involved with the farm. As noted in section 5.2, this creates an implied population of primary operators who are sampled by NASS but are likely to differ from the true target population of farm households.

Ideally, a household/individual frame would include all operators’ households. The operators enumerated are not necessarily the same as the

NOTE: EIN = Employer Identification Number, SSN = Social Security Number.

people who should be listed as contacts for survey purposes. Therefore, the enumeration of persons should include their function and an identifier, if possible.

Also, it has become increasingly important to maintain information on all operators in the list frame, including nonprincipal operators. One reason for this is that data appearing to support claims about an aging farm population may, in part, instead reflect a distortion created by sampling frames that fail to represent a younger population and women due to cultural norms regarding who is thought of as the principal operator (Ridolfo et al., 2016). While more careful creation and maintenance of household links within the farm register would in principle be sufficient to sample farm households, using indirect sampling methods, there are important benefits to creating a separate list frame of farm households. In particular, a farm household list frame would make it possible to include additional households or individual-level auxiliary information, and it would allow for a more efficient, more direct sampling of households.

RECOMMENDATION 5.6: The National Agricultural Statistics Service should create a separate list frame of farm households within the overall Farm Register that would lead to a more efficient sampling of farm households and/or persons involved in farm activities, since the household list itself can be stratified or augmented with auxiliary data.

In so doing, future linkages with tax records or welfare programs could also be facilitated, where appropriate.

Building on the existing operator list frame maintained by NASS, the Farm Register should be a set of relational databases that include information on places and people, identifying households and businesses with suitable links. The Farm Register could also contain household identifiers that could be linked to this frame.

There are benefits with such an approach. For instance, currently ARMS cannot sample households, something ERS should do given its mission to track farm household income and well-being. With this proposed database, ERS could do this. In the case of complex farm operations, it would also simplify the understanding of coverage when the relationship between households and farms is many-to-one or many-to-many. Further, this approach would improve the continuity of operator and household records, and it would also address current issues when the primary operator changed, especially in cases of spouses, two generations of operators (co-principal operators), or partnerships.

5.4. PROPOSED MODIFICATIONS TO THE CENSUS OF AGRICULTURE AND ARMS TO BETTER ACCOUNT FOR COMPLEX FARMS

The panel found that the diversity of topics and conceptual units involved in the Census of Agriculture and the ARMS—concerning businesses, individuals, and households—confuses and burdens respondents, particularly for large complex farms. Adopting a Farm Register, as described in the previous section, would allow ERS and NASS to take a more streamlined approach to both of these surveys, reducing respondent burden and improving the quality of the data collected while still fulfilling all mandates and essential needs.

The panel acknowledges that any major changes to the Census of Agriculture or the ARMS occur only after careful reflection on what is lost and gained by the changes. In the following, we describe one series of promising changes.

Census of Agriculture

The Census of Agriculture should be recast as a source of basic structural characteristics that creates a sampling frame for more focused surveys and that creates reliable small-area estimates for such characteristics. The new Census of Agriculture would be a survey at the farm business (statistical enterprise) level, enumerating all farm and nonfarm activity that occurs within the farm business. It would identify all farm establishments within each farm business, the producers associated with each farm establishment, and the households containing the producers. The information collected in the Census of Agriculture would update information collected on the Farm Register and could thus be used to draw more targeted sample surveys.

NASS and ERS would have to decide what characteristics are needed for sampling or for small-area estimates. The essential characteristics could include

- Farm characteristics: rent land? Irrigate? Use hired labor? Participate in government programs? Family or nonfamily farm?

- Producer characteristics: demographic information, primary occupation, education, households the producers belong to.

- Production characteristics: total sales or value of production, production quantities for particular crop and livestock categories.

Items that could be left for more specialized surveys include these:

- Values for items that are not essential characteristics of the farm (e.g., revenues from horse breeding and stud fees).

- Practice-related questions, unless linked to the focus of a follow-up survey (Section 24 in the 2017 Census of Agriculture),

- Machinery and equipment details (Section 28),

- Production expenses (Section 30).

- Income from farm-related sources (Section 32).

The Agricultural Resource Management Survey

The Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS) and its various phases and versions should be reformulated into an annual component along with specialized, periodic components. The annual component should be a farm establishment survey, which would collect the information needed for measurement of the costs of production and the financial health of farms, including the information needed by the Bureau of Economic Analysis for national economic statistics.

Periodic, specialized surveys could be used for any questions not needed for these purposes or to meet mandates that explicitly require annual collection. Linkages and comparisons between Census of Agriculture records at the farm business level and ARMS records at the farm establishment level should remain possible, using information from the Farm Register. This is particularly important in calculating the number of farms, which would now be measured at the farm establishment level.

Household information should be collected in a periodic survey of producer households. Conducting a household survey every 3 years, for example, would allow ERS to fulfill its responsibility to report on the well-being of farm households. And by maintaining a link between households and farm establishments in the Farm Register, it should be possible to link the operational characteristics of the farm establishment with producers and the associated households. To reduce respondent burden, ERS and NASS should reconsider which households it collects financial information from. This includes reevaluating the merits of collecting household information from households with little involvement in production agriculture or from households involved in very large operations with complex and diffuse ownership.

RECOMMENDATION 5.7: The U.S. Department of Agriculture should consider alternative strategies for collecting information to meet its mandates. The Census of Agriculture could be revised as a farm business survey, and the Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS) could be revised as a farm establishment survey with linkages between farm businesses and farm establishments.

Other information currently collected in ARMS but not needed annually could be collected in specialized, periodic surveys, which could target farm establishments, farm businesses, or fields. These could include focuses on pressing topics, such as antibiotic use or seed technology, or on more general farm topics, such as production practices, labor arrangements, sources and uses of debt, or participation in government programs.