3

Dimensions of Farm Complexity

Farms that are complex, along many dimensions of their business operations, have existed for decades. In fact, it has always been common for families that own and operate farms to also be engaged in other businesses and occupations (Sumner, 1982; U.S. Department of Agriculture and Economic Research Service, 2017). Nonetheless, over time, complex business organizations have become more commonplace in farming. Farming is not unique in this regard; the banking, retailing, and manufacturing sectors have likewise experienced greater business complexity over this same period. But what does it mean to be a complex business? In this chapter, we identify factors that make a farm more or less complex as a business, in an operational and management sense, and how such complexity affects the collection of data from farms.

This chapter focuses on the farm, rather than on the farm household or on demographic or other characteristics or activities of individuals and families that own or operate farms. It is worth keeping in mind, however, that some of the complexity that statistical agencies face when they collect data from complex farm operations is due to the types of demands placed on them to produce information about individuals, households, and families engaged in farming.

The majority of agricultural commodities today are produced by farms that employ more complex business models (Gardner, 2002; Sumner, 2014). The descriptive data from the Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS) presented in Chapter 1 (see Figure 1.2) also indicate that large farm operations dominate market share; the midpoint of production—the point at which one-half of the sector’s production takes place on larger

farms and one-half on smaller farms—is produced on a farm with sales of $1,416,050. These data also show that consolidation of farm production has continued over the last two decades. In 1996, just one-third (33.2 percent) of the value of total farm production was produced on farms with sales above $1 million (in 2014 constant dollars), but by 2014 that figure had risen to 57.3 percent.

The importance of larger and generally more complex farming units has significant public policy implications. Limitations on gross income regularly feature in Farm Bill debates. As an example, current discussions are under way to limit crop insurance subsidies to those farms that have lower gross incomes.1 This has implications for the stability of the crop insurance markets, which certainly could be affected if larger farms were no longer eligible for subsidies and they chose not to participate in the market. Because the current crop insurance system is backed by reinsurers located in Europe, reduced participation could increase the price of that reinsurance or ultimately lead those insuring entities to stop offering that service. Understanding the decisions made by large and complex farms is certainly important as legislators debate policy outcomes.

Bonnen and colleagues (1972) describe how effective data systems facilitate empirical work that, in turn, results in sound agricultural policy and private-industry decision making. The authors argue that the decision-making unit of the farm had become “a heterogeneous and functionally dissimilar set of activities and processes” (p. 868). This heterogeneity of farm operations has only become wider in the ensuing years, creating a need for a more detailed understanding of those farms that produce a majority of the food and fiber produced in the United States.

Public policy makers are concerned with distributional effects on individuals and businesses. To fully understand the differential effects of agricultural, environmental, tax, and macroeconomic policy requires robust data collection measures that cover the full span of the agricultural production sector.

Although large farms, as measured by gross income or production volume, tend to be complex along multiple dimensions that affect the collection of information, size need not translate into complexity. The factors and causes of complexity extend to characteristics beyond production unit size. Indeed, small farms may also be complex, as in the case of small farms that retail their own production at farmers markets or the case of Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) farms, which are vertically integrated to include retail packaging and delivery operations. In a study of 54 CSAs

___________________

1 See https://www.ewg.org/agmag/2018/06/senate-farm-bill-amendment-would-rein-cropinsurance-subsidies-rich#.W5BDoehKhPY.

in California’s Central Valley, Galt (2013) finds that farmers’ profits and economic rents were very difficult to measure.

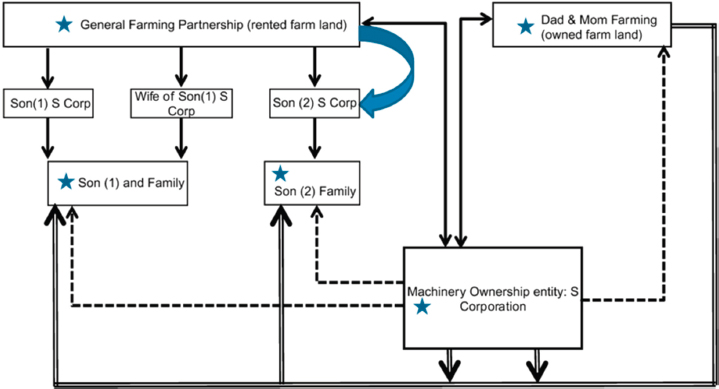

To understand the dimensions of complexity, it is useful to consider examples of farming operations that highlight a variety of farm characteristics. Farm complexity may arise from the interactions between business and family, for example, when family priorities, the timing of business transitions to meet those priorities, and the economic and government policy context affecting those family priorities all come into play. Featherstone and colleagues (2012) consider examples that are useful in understanding this dimension of complexity. Figure 3.1 shows the structure of the owner-operators of a business with farm enterprises that began as a sole proprietorship. The priority was to allow for some of the next generation of the family to be involved in the operation, while facilitating the transfer of assets to others in that next generation who might choose not to be involved in farming. The result was the formation of a general farming partnership, four S corporations, and three individual ownership entities.

Featherstone and colleagues (2012) discuss the complexities encountered in measuring the overall profitability of this total operation, in monitoring its machinery costs, in increasing the efficiency of transferring the assets of the original owners to the next generation, in monitoring family living expenditures, and in positioning the operation for growth. The main objectives in adopting the business and ownership structure depicted in Figure 3.1 were to facilitate the transfer of assets and to manage machinery costs.

SOURCE: Featherstone et al. (2012). Reprinted with permission.

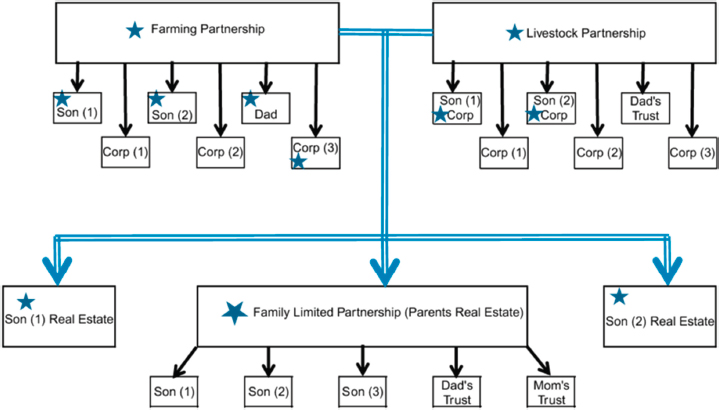

SOURCE: Featherstone et al. (2012). Reprinted with permission.

Featherstone and colleagues (2012) also provide details of a second farm, for which measurement of its profitability was complicated by the fact that financial records for different entities involved in the business were kept separately (see Figure 3.2). This second farm began in the 1940s as a sole proprietorship and consisted of both livestock and cropping enterprises. Of the owner’s three sons, two were involved in the farm operation while a third wanted to limit his participation to the farm’s asset accumulation. To accommodate all concerns, they created a structure consisting of two general partnerships, one limited partnership, three trusts, two S-corporations, and three C-corporations, along with other land-holding entities. Reasons for the formation of the organizational structure included farm program payment limits and tax law advantages—including both increased deductions and facilitation of the transfer of assets from one generation to the next. To obtain a measure of the overall profit of such a farm business, data must be accumulated from different entities, including the personal records from each participant and the C-corporations. Nonetheless, because of the transfer pricing of feed from the cropping partnership to the livestock partnership, income can be attributed to either enterprise for tax purposes.

Featherstone and colleagues (2012) discuss the burden on respondents in the collection of ARMS data (as does section 2.4, in Chapter 2) that are related to the business structure. Answers to questions about farm complexity, even about how many farms are counted, are dictated largely by defini-

tions. Questions about size are measured in several dimensions, including quantity of output, value of output, and land area. Questions about ownership involve the extent of value-added enterprises. Questions about contracting arrangements among entities involve both marketing and production. And questions about relationships with nonfarm activities include related companies, employment relationships with labor used on the farm, and the purchase of input services that combine management, labor, and capital.

Each of the above-described dimensions of farm complexity is discussed below. The recommendations presented later in the report are intended to help guide data collection and facilitate accurate measurement in the presence of these complexities.

3.1. FARM SIZE

As the examples just presented show, farm size is often related to farm complexity, but the measurement of farm size itself is complex. The most useful measures of size differ by enterprise and purpose. Often, in comparisons across farms with different commodity enterprises, size is measured by farm value of production. Area of land harvested, number of livestock, and quantity of production or sales are all useful metrics for comparing farms with the same enterprise or mix of enterprises. However, they are less useful for our current purpose (in this chapter) in the sense that more of a single crop or livestock enterprise does not add to measurement complexity.

Similarly, neither land nor even gross revenue is a particularly useful measure of farm business size when comparing farms that produce multiple commodities, because the mix of productive activities can be so different. For example, 100 acres of strawberries may generate $4 million in cash farm income and, by most categorizations, would be considered a large farm. But a farm with 100 acres of wheat is considered tiny among its same-crop peers. A beef feedlot with $1 million in revenue would market fewer than 1,000 head per year, and is small for that industry, but $1 million in sales for a corn farm is relatively large for grain farms. Farm returns to capital, land, and labor (rather than purchased inputs) are a unifying measure that allows comparing across commodities and enterprises and vertical integration on farms. An example of vertical integration would be the production of livestock feed or carrying of livestock from farrow to finish or from the cow-calf stage through a feedlot.

A value-added measure of a farm—which figures directly into gross domestic product (GDP) measurement, for example—computes the contributions of farm labor, management, and capital to income generation. The larger a farming operation becomes, the more likely it is to be split into stand-alone operations considered separate from the farming activity and, in turn, to be correctly accounted for in the measurement of GDP.

Since the decision of when to separate these activities is made by individual producers, it is difficult to know what percentage of the economic activity is being counted as part of a farm and what is being counted as a separate business. Unfortunately, value added is seldom reported widely for farms, because it demands more data and accounting expertise to construct than the simpler measures of gross revenue and physical outputs and inputs.

One reason larger farms may be complex, as alluded to in Figures 3.1 and 3.2, is that they often have several owners, more complicated legal entities and relationships, issues of transition across generations, and non-operating owners. Larger farms are more likely to farm land areas that are geographically dispersed and to do so with several distinct commodity enterprises. Larger farms also may be more likely to maintain ownership of nonfarm businesses that are linked to the farm enterprises by vertical integration. For example, when a certain scale is reached, the size of the operation may cause a producer to haul grain further with his or her own fleet of trucks to obtain more favorable prices. In turn, to mitigate liability, a farm may create a separate trucking enterprise to limit legal liability for road accidents through appropriate ownership. Hauling farm products to a local market is a typical farm operation; however, an independent trucking company performing a similar function is not considered a “farm activity” in most U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) measurement programs. If, over time, there is a transition from trucking as a typical farm activity to trucking as a separately owned and operated nonfarm business, complexities and ambiguities arise about where to draw the line between the farm and the trucking enterprise. As explored in the next chapter, collection of data about farm activities requires clarity about these definitional issues.

Understanding the returns to the farm versus the nonfarm parts of the business (such as the trucking just described) requires that each component be tracked. In addition, comparing an operation that does not separate different activities in the organization with operations that may result in noncomparable measures of economic performance, depending on how the data are collected and reported.

In summary, farm size itself is not a dimension of complexity for the farm operation or for the data collection, but farm size is often correlated with complexity in other dimensions, and the collection of accurate data from large farms is especially crucial for industry and sectoral measurements.

3.2. GEOGRAPHIC DISPERSION OF OPERATIONS

The presence of multiple locations for farming activities or multiple addresses for farm management sites creates complexities in farm operation and management and, with those complexities, the potential for significant

mistakes in data collection. Results from a survey of National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) field office staff showed that “operations across states/counties” was the third-most frequently selected determinant of farm operation complexity for data collection purposes (Parsons, 2011). When farms operate in multiple counties, data collection and reporting become more challenging for USDA because of the difficulty of assigning production by a single farm to individual counties, which is required for widely used county-level statistics. Biased estimates of statistics such as average yield can lead to skewed outcomes for programs such as crop insurance. Even simple statistics, such as acres by crop by county, may be affected by errors in assigning production correctly to the county or counties of an operation.

Geographic dispersion may also increase survey burden. Respondents in charge of multi-county operations might be surveyed multiple times for the same data fields, leading to their frustration and their lower willingness to participate or to their providing less accurate responses.2 When separate records are kept for the different locations of a farm, county-based estimates are more reliable. However, to ensure that farm size and other indicators are accurate, it is also vital that such records be associated with the correct farm.

3.3. BUSINESSES THAT OPERATE MULTIPLE FARMS OR OTHER BUSINESSES

Some farm businesses encompass several operations that may each be properly considered separate farms, even if they are managed by a single entity. The examples provided in Figures 3.1 and 3.2 show how defining the separate farms can be complicated and even ambiguous unless data collectors use specific, detailed definitions and concepts. Data collection becomes difficult when there is a sharing of capital and related inputs, or when the transfer of an output from one entity is used as an input into another entity when accounting is done for the entire operation, unless there is a clear understanding as to whether those items are transferred on a cost basis, a market value basis, or by some other valuation process. The returns to the farm can change dramatically depending on the value attributed to the sharing or transfer of items between entities. The issues related to geographic definitions are even more troublesome when overarching organizations include operations that do not farm but may provide services to the farms operated by the organization and sometimes provide services that many farms provide themselves. Such services could be as simple as hired farm labor contracting as a separated business unit rather than being incorporated within the farm business unit.

___________________

2 See the discussion of this topic in Chapter 2, section 2.4.

Separate functional operations or legal entities may be established to optimize government program payments, better implement management strategies, limit liability, reduce tax liabilities, or better align risks and returns when ownership shares differ across operations and entities. Succession planning is also important in determining the definition of operations and entities. For certain types of analysis, it may be useful to think of different parts of an operation as different companies; for other purposes it may be more useful to think of all the activities as being part of the same company, including the same farm. For these reasons, measurement purpose must first be well understood in order to structure data collection instruments accordingly.

3.4. FARM-CONNECTED NONFARM OUTPUT

The presence of farm-connected nonfarm inputs and outputs, together with the costs and revenues that they generate, adds to farm complexity. Nonfarm business activities are sometimes closely linked to a farm enterprise and, as discussed above, this arrangement complicates the question of where to draw the line between them, both for the business and for the data collector.

This attribution issue is not complex when income is clearly not farm-related, as in the case of a portfolio of income generating stocks and bonds or of income from a spouse’s nonfarm wage employment. Complications arise when activities are related to a farm but may or may not count as farm activities in the specific context at hand. For example, a grain farm (“farm A”) may provide custom harvesting services for a farm operated by neighbors (“farm B”) using the same personnel and equipment used when harvesting on farm A. When a company specializing in harvesting provides such custom services to farm B, the revenue it generates is not part of farm income. The concern arises when the operator of farm A keeps no separate records and simply includes the costs and returns from the custom harvesting business within his or her own farm accounts. It is conceptually clear that services provided on other farms are distinct from farming but, as a practical matter, this sort of farm-related income raises complexities. It is also conceptually clear that the capital and labor used in harvesting on both farm A and farm B are properly counted as inputs into farming in productivity measurements and other indicators, no matter which firm does the harvesting on farm B.

In nearly all commodity industries—among them grain and oilseeds, livestock, and fruits and vegetables—when considering the processes one step upstream or downstream from the farm it becomes difficult to decide whether or not those activities should be classified as farming. If the statistical methods allow different farms to report differently, it will be difficult

to correctly interpret the data. In addition, when these activities occur in different entities it also becomes difficult to understand the records, depending on how inputs or outputs are priced as they move from one entity to another entity.

Activities downstream from farms that are part of businesses engaged in processing or marketing are sometimes referred to as “value added” activities. This usage of value added should not be confused with the standard economic use of the term—for example, as used in national income accounting—which reflects the contribution of labor and capital to production.

For data collection, the most important characteristic is clarity about the way respondents should report their activities. In some cases, the current reporting relationships are clear. For example, it is clear that cheese processing is not to be reported as a farm activity when it is done by a farm-owned cooperative that is managed separately from the milk production on the farm. In other cases, what farms do or are supposed to do is less clear. For example, when seed cleaning is done by a business operated by a farm producer that also grows the seed crop, and no seeds from other farms are cleaned by the cleaning business, and the seed cleaning is physically located on property connected to the farm, then it may be correctly reported as a farm activity. This is so even though most farms ship seeds to businesses distinctly set up for cleaning. In the case described, farm accounting may be integrated with seed production. The challenge is that farms differ from one another in the amount of post-production processing or services that are incorporated before they “sell” their farm output.

The current approach NASS uses in its data collection on value-added activities can be improved. Currently, those who supply data are not given clear guidance about how to categorize production activities or income. Additionally, information is gathered for several purposes, such as (i) measuring farm income, (ii) measuring farm production quantity, or (iii) measuring how farm and nonfarm activities are linked in a single business. Thus, guidance needs to be provided regarding the data collection so that users are able to understand the purpose for which it is being collected.

Farmer-owned cooperatives are the most common example of separate farm-owned nonfarm businesses. In a cooperative, a group of farms jointly produces or purchases inputs, processes commodities, or markets products through a single firm they jointly own. Farms receive revenue for commodities they deliver to processing and marketing cooperatives, and they gain additional benefits from their ownership proportional to the commodities delivered, which may be received in subsequent years.

Also, many farms are involved in processing inputs that are otherwise conducted by nonfarm firms. For example, animal feeding businesses sometimes operate an onsite feed mill. In some cases, a firm that has an animal

feeding farm also operates a feed mill and sells feed to other operations. The measurement challenge is in clearly delineating when the operation of a feed mill is not a farm activity and, therefore, when its revenue is not farm revenue. Gathering information on the feed mill business is important, whether that business is operated by a farm or not. The general point is that, in some cases, input processing is integrated within a farming operation and no clear market-based transfer prices for milled feed are available to report. In other cases, operating a feed mill is distinctly a nonfarm activity and clear market prices are identifiable for milled feed.

The Penobscot McCrum organization in Maine is an example of a complex farming operation (County Farms, Sunday River Farms) that provides value-added potato specialty products as outputs (Penobscot McCrum) and transport services (JDR Transport) for its farming operations and for other outside companies. In addition, Penobscot McCrum brokers grain (County Grain Merchants), along with marketing and selling both its own potatoes and potatoes for other independent farmers throughout Maine (County Super Spuds).3 The value-added nature of these activities illustrates the potential complexity of data collection, here depending on the valuation of raw material such as potatoes when transferred from the farm to further processing into baked skins or other value-added specialty products.

3.5. FARM EMPLOYMENT AND DATA ON HOURS AND WAGES

Farms use directly hired labor, family member labor, and labor that is employed by a separate firm. When family labor is employed for an explicit wage or salary, it can be treated in the data in the same way as any employee’s labor. Often, however, family members are not paid direct wages or salary, and few clear records of their labor contribution are maintained. This can make it difficult to accurately measure the full labor inputs associated with a farm.

While family labor should generally be treated as farm employment, contract labor is not; such laborers are employed by the contracting firm. Because contract workers are not farm employees, associating their labor inputs with specific farm output is complex. The complexity increases when capital and labor are both engaged in the contract services because, in such cases, records that clearly separate costs between labor and equipment are rarely kept.

To accurately measure productivity and understand labor or capital intensity, it is crucial to collect accurate data on the farm labor used for particular enterprises. For example, if custom labor use rises relative to hired labor in fruit production, and the data do not allow one to associate

___________________

3 See http://penobscotmccrum.com/family-of-companies/index.php.

the custom work with specific crops, it becomes impossible to track and understand the farm’s productivity and related measures on a commodity by commodity basis. Current data collection practices that the USDA’s Economic Research Service uses to measure agricultural productivity seem to be deficient in this regard, and they will become more so as labor is hired at higher rates by nonfarm businesses and those workers perform an increasing share of the nation’s (or state’s or county’s) farm activities.

3.6. FARM AND BUSINESS OWNERSHIP: LEGAL RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN OWNERS AND FARMS

Producers sometimes organize their operations using several companies: one company may own the land, another may own the equipment, and still others may own the livestock; and each may be separate from the company that operates the farms. The owners of these companies may be individuals, trusts, partnerships, or other organizations, and the individuals involved may include family members or others, including unrelated shareholders. On some farms, management is separate from company or asset ownership, and several individuals are involved in each area. In these cases, specific contracts are often used to coordinate activities and to specify responsibilities and rewards.

There are many drivers motivating these complex business and legal organizations. These include incentives to reduce tax liabilities, compliance with rules of government commodity subsidy programs, and incentives to reduce taxes or other concerns in transition of assets and business to new ownership (say, across generations). In Figures 3.1 and 3.2, discussed earlier, both operations began as sole proprietorships. The goals of their reorganizations were similar, but the laws creating tax and other incentives varied, resulting in different legal arrangements across the companies. When farms separate into multiple entities in this way, complexity in both data collection and analysis increases.

3.7. MANAGEMENT AND DECISION-MAKING RELATIONSHIPS

Farms are commonly characterized by management that is spread across several individuals. In this way, farm businesses are not unlike businesses in many other industries. Data programs must be designed in a way that ensures that collection draws on the most knowledgeable person in the organization for each information request. Employees of a large farm business may be able to accurately report farm quantities, prices, revenues, and costs, but the same employees may not be able to respond knowledgeably about management responsibilities or about the relationships among owners and hired managers.

These concerns raise practical complexities when it is unclear who can best respond on behalf of the farm. For a large and complex organization, more than one respondent may be required, depending on the set of questions or the survey. Such a situation with multiple respondents is routine for other industries, and it must become routine in agriculture.4

With the goal of improving data collection from farms that display the characteristics described above, we next turn (in Chapter 4) to the definitional questions that must be untangled as a prerequisite to better measurement of farming and agriculture. After that, it will be possible to provide guidance on the data collection infrastructure and on specific data collection instruments, such as the Census of Agriculture and the ARMS, which we undertake in Chapter 5.

__________________

4 A major farm commodity producer in California recently reported that a Census of Agriculture form mailed to his family home in the hills overlooking Los Angeles was tossed out as junk mail, whereas if it had been sent to the farm offices one of the accounting clerks would have duly completed as much as possible and submitted the forms.