4

Several Models for Sustainable Partnerships and Private-Sector Engagement

The third workshop session focused on four models of private-sector engagement and PPPs and their potential as sustainable, scalable solutions in the current global health environment. The four models explored were catalyzing and scaling promising social enterprises, leveraging core competencies of private-sector companies, engaging other industries, and using technology to increase access.

CATALYZING AND SCALING PROMISING SOCIAL ENTERPRISES

Chris West of Sumerian Partners moderated a discussion with Liza Kimbo of LiveWell in Kenya and Caroline Bressan of Open Road Alliance on catalyzing and scaling promising health-sector social enterprises in LMICs. Kimbo gave an account of her journey from running a retail pharmacy chain to becoming the founder of a health enterprise and one of the largest chains of health clinics in Kenya. Bressan spoke about the fragile existence of health care social enterprises and her work in assisting innovative companies to overcome roadblocks that hamper the path to scale.

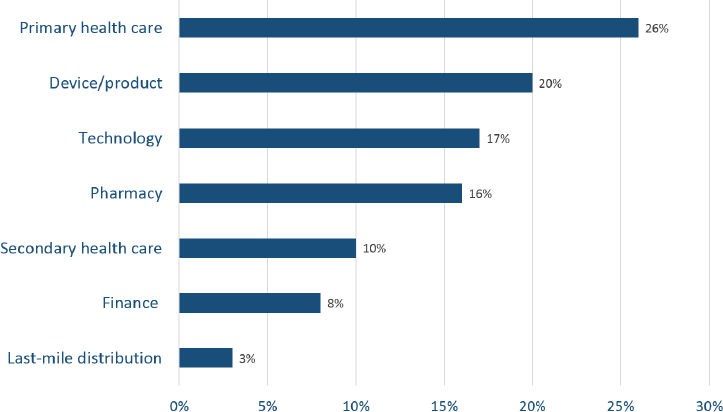

Before turning the floor to Kimbo and Bressan, West set the stage by describing the current state of the social enterprise market. Social enterprises are organizations that apply market-based approaches to the provision of products and services that benefit poorer communities. A social purpose is embedded in their mission regardless of whether they are structured as nonprofits or for-profits. In Africa, his recent research identified 267 organizations that self-identify as social enterprises providing health care to

low-income communities with about half operating as for-profit organizations and the other half as nonprofit. Figure 4-1 displays the breakdown on the market focus of the health care social enterprises in Africa.

This market has evolved primarily in the past decade, and West suggested three reasons for its growth:

- There is increasing demand from low-income communities for good-quality, affordable services and products, and some members of these communities are now more willing and able to pay out-of-pocket for them.

- Secondly, many not-for-profit organizations that require subsidies are struggling to find them, and they are trying to accommodate the decrease in income by charging for products and services that previously were given away for free or at discounted prices. In other words, they are trying to adopt or integrate market-based approaches into what was traditionally a not-for-profit service model.

- Thirdly, younger people are far more interested than previous generations in setting up businesses with a social purpose.

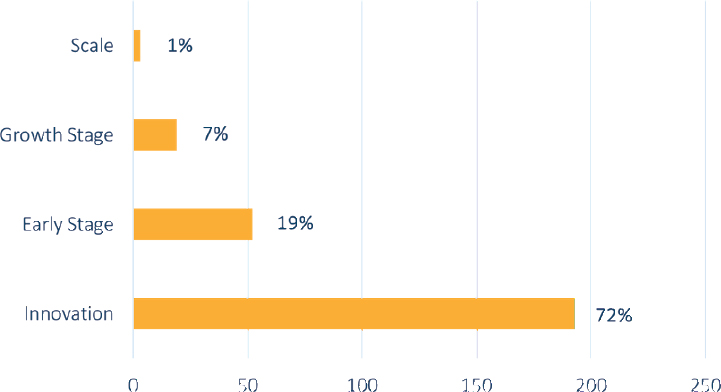

West then described the stages of development for these social enterprises:

- Innovation stage: Concept developed but not implemented

- Growth stage: Moved beyond concept, implemented and generating some level of revenue

SOURCE: As presented by Chris West on June 14, 2018.

- Early stage: Implemented and generating regularized income stream but not yet profitable

- Scale stage: Implemented, financially viable, and expanding

Of these four stages, more than 70 percent are in the innovation phase of their development, and less than 1 percent have reached scale (see Figure 4-2). West shared four factors he believes are necessary for social enterprises to reach scale: an enabling policy environment, appropriate funding, business and technical skills support, and market linkages. To scale, they require an enabling environment to operate and deploy their market-based approach. Appropriate funding is needed but in a form and duration consistent with the need to make an impact and boost scale-up. Business and technical skills are also needed, as are links with other enterprises in the private or public sector or with civil society organizations. Generally speaking, the market in Africa, in West’s view, is vibrant, sizeable, and diversified, but it lacks the four factors needed for social enterprises to scale and the market to reach its potential. In terms of support available for social enterprises, West shared that support generally exists as short-term grants during the innovation stage and investments seeking return on capital when organizations have scaled. He emphasized the lack of support available during the growth and early stages.

Following West’s description of the health care social enterprise market in Africa, Kimbo shared her experience as a social entrepreneur operating within the sector. Her journey started 20 years ago when she

SOURCE: As presented by Chris West on June 14, 2018.

opened a chain of seven retail pharmacies in Nairobi. Her initial motivation for opening the pharmacies was purely a business decision. She quickly realized that about half of the people who walked into her pharmacies walked out without having their prescriptions filled because of the high cost of her branded products. Recognizing the failure in this business model, she sought out good-quality generic drugs that would be affordable for the community, thereby expanding her market base. Eventually, she joined another entrepreneur to collectively set up community drug shops in rural areas. This business model evolved into several franchised primary health care drug shops and ultimately expanded to primary health care clinics staffed initially with community health workers and finally with nurses. The clinics are still running. “That is one of the most exciting things that I have done,” she professed. She started her enterprise on a for-profit basis for the wealthy who could afford expensive medicines and eventually ended up on a nonprofit basis for people who could afford to pay only a small sum of money.

This nonprofit model, she said, survived through donors and enabled her to create LiveWell, a sustainable network of clinics and hospitals. LiveWell’s first objective was to provide primary health care services to the poor communities of Nairobi, where she opened five clinics providing primary health care services, especially for mothers with young children living close to the clinics. After going through many transitions on a learning curve, she decided to take over a small 30-bed hospital from a large flower farm company in a rural area of Kenya. The flower farm companies in the area, she said, wanted their workers to receive basic primary care at an affordable cost. The flower farm companies, therefore, support the hospital by paying a statutory fee for their 4,500 workers. Kimbo extends her hospital’s health care services to the community and their families. The workers are also covered by Kenya’s National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF), which pays them about $1.00 for outpatient services and certain inpatient services. The hospital is open 24 hours per day and works closely with the Ministry of Health, which provides vaccines and family planning commodities and functions as a reference hospital. The NHIF covers the hospital’s outpatient and inpatient services. USAID partners have set up a comprehensive care clinic at the hospital and have provided support for its staffing and for HIV commodities and TB products. Kimbo’s ambition is to set up a much-needed mini-surgery center; currently, her hospital refers three to five women per week for cesarean sections that could be performed onsite if there were a surgery center.

The next speaker, Bressan, drew laughter from the workshop participants by saying that social enterprises are the working poor of the business world. But the reality is, she said, one shock and they drop below the poverty line. They live hand to hand, and even in the United States, they

cannot find affordable capital, and when they do, it requires collateral that is often overly cumbersome. She described the growth pattern for social enterprises as: growth, growth, disaster; growth, growth, disaster; and constantly needing to rebound without any safety net.

This is where Open Road Alliance fits in, Bressan explained. The organization is a private philanthropic initiative founded to keep social enterprises and their impact on track. It provides contingency financing in the form of grants and loans when unexpected roadblocks occur. About one in five projects experiences an unexpected need of funding. Much of its work is in sub-Saharan Africa.

Open Road Alliance has data, she said, that identify the types of roadblocks social enterprises experience.1 Ultimately, the organization will develop a robust dataset that can predict what the top three roadblocks a health care social enterprise, for example, is likely to run into, what its roadblocks might be, and what solutions can be applied. From the currently collected data, Bressan said one of the most frequently identified roadblocks is delayed fund disbursements. Bressan cited an example of a company in Nairobi that Open Road funded recently. The company uses ambulances that must reach a point of medical assistance within 15 minutes of an emergency. There are plenty of ambulances in Nairobi, but, so far, there has been no method of ensuring that the ambulance closest to the emergency is the one dispatched to it. The company therefore created a central system that works across different private hospitals and ambulance providers to dispatch the ambulance closest to the location of an emergency. When the company was raising its seed round of investment their lead investor had a heart attack. Open Road stepped in with a bridge (short-term) loan to keep their impact on track.

Another example she gave involved an organization in Rwanda, similar to Liza Kimbo’s LiveWell, called One Family Health. The organization, Bressan explained, is run as a franchise clinic model that works with rural clinics operated and owned by skilled nurses and integrated in the county’s national health insurance program. The organization serves about 10 percent of the population. Unfortunately, the government of Rwanda sometimes delays its payments, so the organization needed a bridge loan to purchase the equipment and drugs in order to continue providing their services. Delayed receivables are also frequently encountered by social enterprises, Bressan noted. They are caused, she said, when a company does not have access to a working credit line from a local bank. The result is a freeze up of the whole company. Another roadblock

___________________

1 To view the Open Road Alliance’s Roadblock Analysis, see https://openroadalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/ORA-RoadblockAnalysis-DigitalPDF-Final-4.23.18.pdf (accessed October 23, 2018).

occurs when a social enterprise unexpectedly receives a large purchase order and does not have the financing to deliver on it. This situation is an opportunity for scale where Open Road can step in.

A second set of roadblocks, Bressan continued, is caused by mishaps to the organization. Bressan cited as an example a chief executive officer in Ghana who contracted dengue and had to leave the tropics for good. Robberies in the offices of an enterprise are also in this set of roadblocks, as are health care partner problems, which are beyond the organization’s control. The third set of roadblocks is what Bressan calls acts of God or economics. This category includes weather events, currency devaluations, and changes in government policy that create liabilities overnight.

As a philanthropic initiative, Open Road believes most of the funds it disburses should accrue to the social entrepreneur. Therefore, the organization offers the loans at below-market interest rates.

Discussion

The discussion opened with a question from James Jones, executive director of the ExxonMobil Foundation. He noted that there are more than 1 billion women in the world lacking access to financial services. He questioned Bressan if this discrepancy existed in the social enterprise sector. Bressan said that her portfolio gave a figure of about 16 percent for the proportion of women founders in the United States. Only 3 percent of female founders are receiving funds, she said. She mentioned that at the 2018 Skoll World Forum on Social Entrepreneurship the discussion turned to sexual harassment of female founders. All of the female founders who participated in the discussion said they had experienced some form of sexual harassment in the course of their fundraising activities. On the issue, Chris West said that over the past 10 years of setting up and funding more than 150 social enterprises run by men and women, he has found no difference in the quality or competency of the organizations; however, women were significantly less funded than men.

David Greeley with the American International Health Alliance asked Kimbo about how successful the USAID support of social franchising and social marketing programs has been. Kimbo confirmed that the USAID funds were crucial and, in addition to the funds, USAID provided technical assistance that was extremely helpful in the training and setting up of the necessary systems. USAID’s technical assistance, she said, was well tailored to the recipient organization’s level of development and its needs. Lin explained that USAID, as a donor agency, is exploring how best to help bridge the “valley of death” (i.e., the difficulty of covering the negative cash flow in the early stages of a startup before their new product or service is bringing in revenue) so that social enterprises can reach the scaling stage.

Kimbo admitted she is obsessed with scale issues and what they imply for her enterprise. Many of the investors that she meets are keenly interested when she is at the innovation stage, and they expect that over the next 5 to 7 years, she would have achieved scale and have graduated from assistance. She says that LiveWell is still far from scale. She notes also that her experience with roadblocks differs somewhat from the delayed disbursements that Bressan mentioned. Kimbo puts disruptive changes in donor strategy at the top of her list.

Ending the discussion, West shared that he believes there is a fundamental misperception of the risk in the market for financing social enterprises. He feels it is on the global health community—the public sector, donors, and investors—to collect the data and better understand the market risks and potential.

LEVERAGING CORE COMPETENCIES OF PRIVATE-SECTOR COMPANIES

Simon Bland of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) moderated a discussion on how the private sector can partner with governments and communities to address health needs. Nduku Kilonzo of the National AIDS Coordinating Council of Kenya described the government’s health priorities and approaches to engaging the private sector to address them. Ties Kroezen from Philips explained the company’s transition from a technology to a health and well-being business and ultimately how this journey led to PPPs to reach new populations in Africa. Allison Goldberg from the AB InBev Foundation described the foundation’s efforts to reduce NCDs by addressing the underlying risk factors of alcohol misuse. Leandro Piquet from the University of São Paulo shared his experiences engaging with the AB InBev Foundation in Brazil as part of this initiative. Westley Clark from Santa Clara University explored the conflicting tensions that can arise when industry engages in global health and how companies with potentially health harming products can contribute to public health.

Leveraging the Private Sector to Meet Kenya’s Goal of Universal Health Coverage

Kilonzo began her presentation by sharing the Kenyan president’s big four agenda: food security, affordable housing, manufacturing, and affordable health care for all. The goal of universal affordable health care includes three specific targets:

- Insurance coverage and access to services for the country’s 51.5 million population by 2022

- Delivery of all quality services

- No more than 12 percent of out-of-pocket household expenditures used for health services by 2022

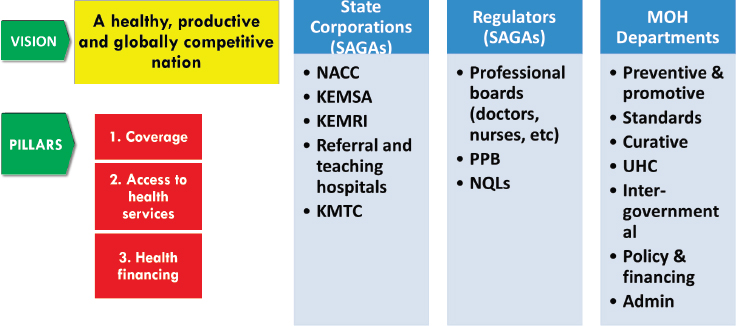

The government has identified 11 drivers for achieving these targets grouped under three focus areas: coverage, access to services, and financing. Kilonzo pointed to one specific driver—attracting $2 billion of private-sector investment for the country’s health sector. While it may seem Kenya is only focused on bringing in private-sector funding, she emphasized the importance of leveraging private-sector expertise to achieve universal health coverage. The leveraging of this expertise typically manifests through PPPs, and Kilonzo explained there are several entry points for where PPP engagement can begin. Figure 4-3 illuminates these different gateways for engagement by illustrating how the way in which the Ministry of Health is organized offers opportunities for different forms of engagement. The examples of different forms of engagement are listed in Figure 4-3.

Before sharing several examples of how Kenya is already engaging with the private sector, Kilonzo described the transitions the country is

NOTE: KEMRI = Kenya Medical Research Institute; KEMSA = Kenya Medical Supplies Authority; KMTC = Kenya Medical Training College; MOH = ministry of health; NACC = National AIDS Control Council; NQL = National Quality Control Laboratory; PPB = Pharmacy and Poisons Board; SAGA = semi-autonomous government agencies; UHC = universal health coverage.

SOURCE: As presented by Nduku Kilonzo on June 14, 2018.

experiencing and the current state of private-sector provisions for health services and financing. Kenya has a fast-growing economy, Kilonzo noted, and by 2030 the country hopes to achieve a middle-income development status. Seventy percent of the population is under the age of 35. The country has also experienced a number of epidemiological transitions, including considerable declines in child, maternal, and adult mortality rates, as well as declines in the burden of HIV and malaria. Deaths from NCDs, however, have escalated over the same period. A big question for Kenya is how the private sector can help address this rising burden of NCDs.

Turning to the current public–private mix of health facilities and health financing, Kilonzo shared that the private sector owns slightly more than half of the country’s health facilities, but most are low-level facilities, such as clinics, dispensaries, and nursing homes. With regard to domestic financing, the private-sector contribution, which includes out-of-pocket expenditures, accounts for almost 60 percent of domestic health financing. Donors account for 31 percent. The government’s share of health expenditures increased from 34 percent to 40 percent between 2012 and 2015.

Kilonzo then described several examples of how the ministry of health is engaging with the private sector. The ministry is currently engaged in a $1 billion medical equipment supplies PPP program that leverages the private sector for a variety of hospital items linked to product management and capacity building. The implementation of the program started in 2014–2015, and it will extend over 7 years. The program manages the supply of all manner of equipment in various facilities around the country, from an intensive care unit to radiology equipment to a central sterile services department. Another project is a pilot e-health project run by three business corporations: Huawei, Philips, and Safaricom. The project provides electronic medical records and a video-conferencing application to facilitate communication between doctors. The project is being tested in one remote county.

A third example Kilonzo shared is the first lady of Kenya’s Beyond Zero movement to leverage resources from the private sector to fund clinics and mobilize political support to create awareness of the need to stem mother-to-child transmission (MCT) of HIV. As a result of the contribution, Kilonzo noted, MCT rates almost halved between 2013 and 2018.

Kilonzo then described two of Kenya’s semi-autonomous agencies. One is the Kenya Medical Supply Authority that manages the national health commodities and procurements. The authority successfully transitioned into a business model, with the government selling products to the ministry of health at below-market prices and acting as a single supply chain for the country. With good forecasting and quantification systems, this supply chain has not had stock-outs of strategic commodities in the

past 4 years, Kilonzo said. Kenya’s second semi-autonomous agency is the National AIDS Control Council and a Kenya HIV and Health Analytics Platform established through an engagement with UNAIDS and IvEDIX, a digital technology company. The analytics platform uses artificial intelligence to provide visual graphics of many HIV indicators. It draws data from several different sources: the ministry of health, the Kenya Medical Supplies Authority (KEMSA), Hom (a logistics and supply company), and a community data system that is run by the National AIDS Control Council. The platform gathers these indicator sources into a single ongoing format. This, again, is a private-sector partnership. Kenya’s national hospitals have various private-sector engagements and some large facilities, such as multispecialty hospitals.

In closing her presentation, Kilonzo reflected on several challenges and considerations. Engaging with the private sector for domestic financing requires finding the win–win solution to balance what a country needs and what a private-sector company wants to give. Related is the question of country ownership: What is country ownership and who defines it? A final point is: Is the global health community actually ready for a new system in which countries have transitioned to fully financing their full health systems?

Philips’s Journey to Primary Care in Kenya

Providing an example of leveraging a private-sector company’s competencies to support a country’s health priorities, Kroezen presented Philips’s journey into primary care in Kenya. In this journey, Philips is using its competencies in innovation—both technical and business model innovation—as well as its willingness to take risks and its ability to execute at scale.

Before sharing the journey into primary care, Kroezen provided some background on Philips. Philips is a multinational company that, over time, transformed from a diversified technology company into a company focused on health and well-being. In 2010 Philips redefined its mission to improving the lives of people through meaningful innovation and set a target of improving 3 billion lives annually by the year 2025. By 2017, Kroezen shared, the company was reaching 2.2 billion people. Its goal now is to reach an additional 800 million people over the next 7 to 8 years. Philips realizes those 800 million people will mostly be in LMICs living in new operating environments for the company. With this realization, Philips decided to focus on Africa, the region where the company’s footprint is the smallest.

Five years ago, Philips began to develop innovations specifically targeted for reaching new communities in Africa. Kroezen shared that

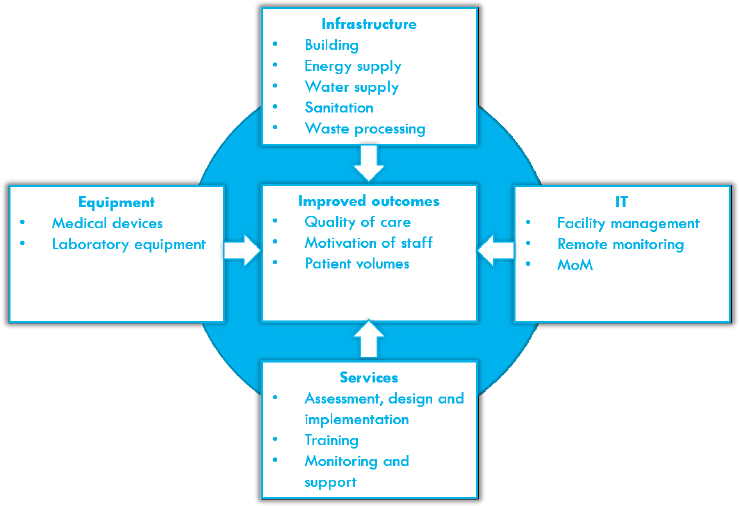

the company decided to focus on primary care, which is where it saw the most efficient and effective opportunities for improving health outcomes among the health care system in Africa. The company’s research into primary health care indicated a number of challenges to be addressed in order to bring sustainable improvement. As a result, Philips developed a holistic solution for community and primary care—the Community Life Center value proposition, or CLC (see Figure 4-4). This modular solution combines infrastructure, equipment, and information telecommunications services with the aim of improving health outputs and outcomes. Currently, Philips operates five community life centers with projects operational in Kenya, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and South Africa, and it has a pipeline of approximately 25 projects in development. Kroezen emphasized that Philips is motivated to expand the model for business as well as social impact reasons. The company expects that the primary care model can develop into a large and profitable business for Philips over the coming years.

In rolling out the CLC solution, Philips learned it needed different business models depending on the county, scope, and source of financ-

NOTE: IT = information technology; MoM = mobile obstetric monitoring (Philips application to improve management of pregnancies across multiple levels of care).

SOURCE: As presented by Ties Kroezen on June 14, 2018.

ing. Kroezen described these different models. For the large-scale project model, Philips’s role is to either build or improve existing facilities. The government pays for the investment, often with financial support from donors, and in most cases, a service contract is included to ensure operational sustainability beyond the implementation. In a managed service equipment model, Philips sells its solution as a service at a fixed service fee, including financing of the initial investment, ongoing training of users, and maintenance. This model was used for upgrading hospitals in Kenya and is now being explored as an application in primary care. In a third model, the PPP model, Philips bears significant risk and management responsibility, and its remuneration is linked to performance.

Kroezen described a PPP model for primary care that is being implemented in Makueni County in Kenya. Philips developed this PPP model with Amref, the largest African-based health nongovernmental organization, and the government of Makueni County, 1 of the 47 counties in Kenya. This model seeks to improve the primary care system in a number of ways, including building community health units, aligning the portfolio of services with the national standard, and upgrading facilities with the CLC solution. The government is outsourcing management of the facilities to Amref and Philips. To make the model financially sustainable, Kroezen shared, it will introduce new revenue streams, including a capitation fee from the NHIF. The feasibility of the model is being tested in three facilities in Makueni County with plans to scale it to other facilities in Makueni and beyond. Philips is working with the SDGs Partnership Platform in Kenya to test and scale the model. Kroezen emphasized that a private company like Philips cannot work alone to develop a new business solution in this market. Partners to complement the company’s competencies, Kroezen said, are necessary to develop a solution.

Discussion

A workshop participant asked Kroezen how the company counted the number of people whose lives it had improved. Kroezen replied that the measurement of lives the company has improved is based on the number of products the company sells. Every Philips product carries a specific indicator, he said, that allows the count to be made. Kroezen said that there is an explanation on the company’s website of the measurement procedure. Another question to Kroezen came from Katherine Taylor from the University of Notre Dame. She wanted to know if Philips had a commitment with the Kenyan government to provide more skilled workers. Kroezen explained that the company will hire and train health workers in Kenya’s Makueni County. Initially they will still be employed by the government but funded by Philips. Ralston asked Kroezen if his company

was coordinating its engagement with the many other companies engaging in Kenya. Kilonzo responded, noting that coordination of engagements of the private sector is an issue that is emerging, especially with development partners and nongovernmental organizations. In regard to the hiring of trained workers, Kilonzo said that the issue goes beyond the hiring of additional staff; it also concerns the retooling of existing staff. When Philips adds health care workers, she said, they will have to operate in accordance with the “people with significant control” guidelines on human resources.

Partnerships to Address Harmful Alcohol Use

Goldberg, Piquet, and Clark collectively presented a PPP model focused on addressing an underlying risk factor for NCDs—harmful alcohol use. The partnership model presented was instigated as part of AB InBev’s Global Smart Drinking Goals. One of AB InBev’s four Global Smart Drinking Goals is to reduce the harmful use of alcohol by 10 percent in six cities around the world by 2020 and to share best practices by 2025. Partnerships to reduce harmful alcohol use have been implemented in the following cities: Jiangshan, China; Zacatecas, Mexico; Columbus, Ohio, USA; Leuven, Belgium; Brasília, Brazil; and Johannesburg, South Africa.

The PPP model presented engages the alcohol company, AB InBev, the AB InBev Foundation, academia, local government, civil society, and other local organizations to reduce the harmful use of alcohol in Brasília. Before turning to Piquet to describe how the partnership in Brasília is operating, Goldberg explained the motivation for the AB InBev Foundation to address the harmful use of alcohol. The partnerships that it supports present an opportunity to meld its public health goals with the approaches and resources of a range of actors, including a large public corporation, to address harmful alcohol use. With the caveat that she cannot speak for the company, Goldberg also shared some of the publicly stated reasons why AB InBev supports the Global Smart Drinking Goals, including that the company recognizes that the harmful use of its products is bad for its consumers, governments, and society.

Piquet then described the partnership in Brasília. Starting in 2016, the PPP has been operating through a local steering committee that includes the federal district government, local and national nongovernmental organizations, Brazilian universities, AB InBev, and the AB InBev Foundation. The partnership focuses on addressing three areas: road safety, screening and brief interventions in health care settings, and underage drinking. The steering committee makes decisions on how to guide the partnership, Piquet explained, and consultants have day-to-day contact with local authorities to monitor activities.

Piquet described the partnership’s activities to address underage drinking. In collaboration with the local board of education, the partnership runs a school-based initiative for students 13 to 17 years old. Piquet’s team is developing educational programs with the support of local nongovernmental organizations that target teenagers living in the most vulnerable neighborhoods surrounding Brasília. Alcohol sales outlets are being trained to raise awareness of underage alcohol consumption, and social norms campaigns are being implemented to reduce underage drinking. A performance indicator used for this initiative is the percentage of alcohol consumed by people under 18 years old as measured by an annual survey independently conducted by HBSA, the leading measurement and evaluation partner of the Global Smart Drinking Goals program, that is supported by the AB InBev Foundation. Piquet also emphasized the success of the Global Smart Drinking Goals’ road safety program, which, according to the government, has averted an estimated 144 deaths during the 16 months that the program has been running. The program uses a data management system with consolidated data from civil police recurrence reports, state morgue death declarations, and the Health and Public Safety Secretaries in order to measure trends in road safety on a monthly scale (AB InBev, 2018). This program is in the process of being independently evaluated by HBSA.

Following Piquet’s description of one of the city partnerships the AB InBev Foundation is supporting, Clark addressed the question of whether a company that makes potentially health-harming products can contribute positively to public health. Based on his 30-year career in the public sector, Clark knows government alone cannot fund all of the needed public health research or practical solutions. While some may prefer a pure public-sector model, Clark feels “perfect” should not be the enemy of “good.” There are ways the private sector can contribute to public health; however, there are important risks that the public health community needs to safeguard against when engaging with industry.

Clark emphasized the value of engaging the public sector for filling the gap in public-sector resources and providing long-term thinking and strategy. However, the public health community, he said, should recommend and monitor how to minimize potential for conflicts when industry is engaged. Conflicts arise when there is the potential for financial gain or professional advancement, the desire to do favors for colleagues, and the tendency for individuals and organizations to want to please those who are paying for their work. Clark suggested that conflicts can be mitigated through transparency about who is funded by whom, who decides how much is funded, how the programs operate, who makes the programmatic decisions, and also about exercising recusal when appropriate. When a partnership engages a company through its core competencies,

several additional steps are needed to manage potential risks, Clark said. These steps include education and communication to ensure program goals remain constant, robust and fully independent evaluation, and scrutiny of public health advisors. Global Smart Drinking Goals has a technical advisory group, of which Clark is a member, that provides scientific review of the activities, monitors potential for conflicts and risks, and also provides technical guidance.

ENGAGING INDUSTRIES IN OTHER SECTORS

Katherine Taylor of the University of Notre Dame moderated a discussion panel that illuminated the motivations and opportunities for private-sector companies in industries outside of the traditional health sector to engage in activities to improve health in LMICs. Two speakers from ExxonMobil, James Jones and Deena Buford, presented a dynamic account of how ExxonMobil engages in health-related activities and gave perspective on the company’s internal collaborative model for global health engagement. The final speaker on the panel, Benjamin Makai from Safaricom, explained why and how the Kenya-based telecommunications company expanded its focus to include partnerships with the government to address health.

ExxonMobil’s Approach to Global Health

Jones began by stating three points he and Buford wanted to convey to the audience. First, ExxonMobil’s approach to global health is born out of business imperatives. He is often questioned, he said, about why a multinational oil company makes significant investments in health. ExxonMobil’s engagement in global health started in earnest with the merger in 2000 of Exxon Corporation and Mobil Corporation, Jones recalled. At that time, the company was constructing a pipeline from Chad through Cameroon to the sea. The main cause of loss of productivity among the pipeline workers was malaria. These productivity statistics made senior management take notice of the health threats to the company’s business.

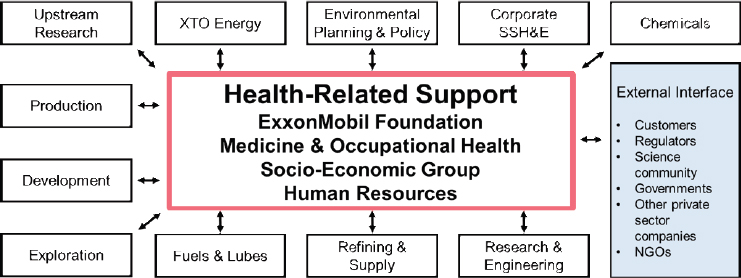

The second point is that ExxonMobil’s approach to global health is holistic and integrated across the company. Both Jones and Buford hold integral roles within this approach, but it goes beyond them. Jones showed a chart of the different parts of the company that are part of the approach (see Figure 4-5). The third point Jones and Buford wanted to convey is the importance of the company’s work through the foundation and grants that support the other functions and objectives of the company.

NOTE: NGO = nongovernmental organization; SSH&E = safety, security, health and environmental performance; XTO Energy is an ExxonMobil subsidiary.

SOURCE: As presented by James Jones and Deena Buford on June 14, 2018.

Buford then described her role as global medical director within ExxonMobil’s approach. Buford provides oversight and guidance to the company’s Medicine and Occupational Health Department. Her department is tasked with providing health support wherever ExxonMobil is operating in the world. The company maintains a contingent of 90 clinics across 30 countries. A call for support, she said, could come from a platform in the North Sea or from a seismic vessel offshore in Vietnam or from the Arctic Circle. It could literally be anywhere, she said. Wherever they are located, she notes, there must be a health plan in place to address the needs of any caller. Clinical services account for a major share of the department’s activities, Buford shared. The service required could be on a primary health care level and could be needed where a local health care delivery system is unable to respond. The company also has an industrial hygiene unit that provides information about ambient conditions that could be detrimental to workers’ occupational health and safety and that require safety measures against exposure to chemicals, radiation, and other hazards. The medical department also has a substance abuse and testing unit and an infectious disease unit. Often, if there is an outbreak somewhere in the world, it will probably affect one or more of the company’s operations, she asserted.

A technical operations and support unit is also part of the Internal Medicine and Occupational Health Department. ExxonMobil, she noted, is, in a sense, a conglomerate of different companies, each with its own mission and its own way of working. They operate in different areas, encountering different hazards and coping with different health care needs. Before thinking about the company’s external partnerships,

ExxonMobil personnel have to think about the company’s internal partners, about who they are, what are they doing, where are they doing it, and what they need. It is a very dynamic operating environment, she notes, and this underscores the company’s business imperative for investing in global health.

Safaricom’s Health Partnerships

Makai began his presentation by noting that Safaricom is a much smaller company than ExxonMobil, and it primarily focuses its engagement in health within Kenya, where the company is based. Makai explained that Safaricom is a for-profit telecommunications business that recognizes its mission to address the unmet needs of society that extend beyond its core mobile communications services. Makai is often asked why Safaricom engages in health partnerships, and, in response, he emphasizes the company’s purpose-driven mission, which prompted Safaricom to embrace the SDGs as an operating strategy. When the company made the decision to embrace the global goals, the first question that arose, he said, was what the SGDs could do for Safaricom.

A glance at the company’s strategy and mission turned the question around to what Safaricom can do for others. Indeed, he said, the company’s mission is to transform the lives of its subscribers, who are mostly Kenyans, and to identify specific SDGs that align with the company’s overall strategy. The firm identified nine SDGs, he said, and aligned them to Safaricom’s corporate vision. The company has gone a step further, Makai noted, to ensure that all its employees link their work to an SDG. This step, he said, has changed the employees’ outlook on their work and on their lives. Safaricom is effective in providing financial services, in setting up pay stations, and in making sure that a call can be made between one person and another. But how does it respond, he asks, to a woman who needs a nurturing continuum from the time she became pregnant to the time her baby is 5 years old? Safaricom attempts to address this question through its engagement in health.

Most Africans have a mobile phone, Makai notes, and Safaricom is taking advantage of the extensive deployment of mobile phones to ensure that its subscribers have access to quality health care. It engages in a number of strategic partnerships with the Kenyan government to bring its technology solutions to the health issues the government is trying to address. From its beginnings as a mobile phone company, it has undergone a metamorphosis that brings it into new areas of interest, such as health, education, and agriculture.

Discussion

Taylor began the discussion by asking Jones and Buford how the ExxonMobil Corporation and foundation work together. Jones replied that the ExxonMobil Foundation does not take direction from the corporation. It has a board of trustees that approves a 3- to 5-year plan. The plan determines what the foundation should be funding. Jones explained the foundation’s strategy has shifted over time, and the current focus is primarily on health care infrastructure and capacity building in the areas where it is operating. Jones emphasized the fact that the foundation’s support does not replace that of governments, agencies, or international health authorities.

The programs that the foundation is supporting help with government relations, advocacy, communications, media relations, advertising, project management, fundraising, chemical engineering, technical assistance, epidemiology, monitoring and evaluation, procurement, and human resources. The foundation, he added, has one of the largest repositories of malaria blood samples in Africa, he said. Buford explained that ExxonMobil’s Medicine and Occupational Health Unit does not provide grants. However, its clinics build relationships with local communities’ health systems across all of the locations where the company is operating. The chances are, she said, that whatever problems these communities are experiencing are probably very similar to those that her unit is experiencing, so that when her unit has found a solution to the problem, they can share it with the community’s health professionals.

Taylor asked Makai to describe how Safaricom structures its engagement in health. Responding, Makai explained that Safaricom encompasses a business and a foundation, and the two incarnations work hand in hand. The essence of what Safaricom does, he continued, is to work with people in delivering a desired solution. The organization’s expertise is in mobile phone technology, but partners, he said, usually come with solutions that are specific to health, education, or agriculture. The organization judges a solution from either a business perspective or a social goods perspective. If the solution is likely to have a commercial potential, it is moved into the business unit. If it does not have an immediate commercial prospect, it is incubated through the foundation.

ADVANCING DIGITAL DEVELOPMENT AND ACCESS FOR HEALTH

Jennifer Esposito from Intel moderated a panel on digital health, the workshop’s fourth and final panel. Esposito opened by relating the excitement about the recent acceleration in interest in digital technology

for global health. She pointed to the digital health resolution, sponsored by India and several other countries, that the World Health Assembly passed as one example of the recent increases in attention to the topic. She also mentioned a forthcoming report from the Broadband Commission, spearheaded by the Intel and Novartis Foundations, focused on providing practical recommendations for scalability around digital health.

Turning to the panel session, Esposito listed the main topics that would be covered in the discussion: national strategies for digital health; creating digital PPPs, particularly in transitioning countries; and increasing donor collaboration for digital goods. The panelists included Olasupo Oyedepo from the Health Strategy and Development’s Information and Communications Technology (ICT) for Health Project in Nigeria, Brendan Smith from Vital Wave, and David Stanton from USAID.

Oyedepo began by describing the current state of digital health initiatives in Nigeria. In April 2016, Nigeria’s National Council on Health, the country’s highest policy-making body in health, approved a national digital health strategy. Following its approval, the minister of health set up an ICT department and, within the ICT department, a national e-health program management office charged with the day-to-day operations of the implementation. Since that time, the ministry of health, under the leadership of the minister, has set up the necessary governance structures called for in the national strategy.

Oyedepo shared that it has not been a smooth journey, and one of the biggest challenges has been capacity building. However, he also highlighted the progress achieved. The governance is in place, political will from the minister has been strong, the minister of health and the minister of communications are chairing a national e-health steering committee, and the national e-health program management office is starting to take a lead and provide coordination and guidance in digital health investments across the country. The national e-health program management office is multisectoral and includes staff from the departments within both the ministry of health and the ministry of ICT. Oyedepo also reported that a number of Nigerian states have implemented digital health programs. Frequently, Oyedepo said, these programs are in the form of PPPs.

Government leadership on digital health is, in Oyedepo’s opinion, the primary reason for these successes, particularly for PPP implementation. In his experience, the private sector’s biggest challenge in working with the public sector has been a lack of direction and a lack of commitment from government. When there is direction, governance, coordination, and commitment, transparency is not too far down the road, he said. Once there is transparency, there is a better sense of a level playing field, and the private sector is a lot more comfortable entering the market.

Building on this issue of political leadership and will, Oyedepo shared a reflection on the state of donor transitions in Africa. He recounted that political will on the part of host governments was brought up multiple times throughout the workshop as necessary for successful transitions. The question Oyedepo had is this: Do the donors and other partners have the political will to make these transitions successful and sustainable? In his opinion, no matter how large the investments donors make in health, these investments will all come to naught if a transition is made without making sure there is an appropriate skill set and capacity in place on the ground after the transition. Oyedepo used the example of the skilled labor force that has been developed in countries to support externally funded programs. When donors transition out, a labor force is left behind that is accustomed to earning sizably higher wages than the typical domestic wage earner earns, he said. What will happen? Oyedepo suggested these workers would leave the country. New infrastructure and programs may be left behind by donors but without the appropriate labor force to run them.

As his final point, Oyedepo emphasized the value of PPPs that capitalize on private-sector knowledge and expertise. He mentioned a digital health leadership program being developed across the continent with the goal of training a skilled digital health public-sector workforce in Africa. This program presented a ripe opportunity for building partnerships with the private sector for skills training through mentorships. Through such mentorship, private-sector experts can transfer basic efficiency skills to help public-sector employees perform their jobs better and ultimately deliver higher-quality outputs.

Turning to the next speaker, Smith discussed the challenges with developing business models for digital health PPPs and shared use case examples of both where it has and has not worked well. When Smith first started working in digital health one decade ago, he said it was assumed that for any projects to reach long-term scale or financial sustainability, they cannot be over-reliant on grant funding, and the private sector would need to be involved. Digital health programs develop, launch, and maintain complex software and hardware solutions, which is an area that goes well beyond the core competency of most ministries of health or, indeed, many areas of government. Business expertise about how to launch and maintain software is necessary in many digital health programs. However, many private-sector companies have been challenged trying to develop successful long-term business models for their engagement in digital health.

The idea that PPPs could be playing a big role in digital health intrigues Smith, but he cautioned it is important to think about the use cases where they could be a successful business model. He shared a few

use cases that have been promising for sustainable PPPs. The first use he shared is the use of mobile phones for tracking the distribution of drugs in a mass drug administration campaign. In this case, pharmaceutical companies are the private-sector actors with incentive to invest in the model. The PPP might give them valuable data on how their supplies are being distributed, as well as allow them to track and manage counterfeits in the market and get on top of that problem. Another use case Smith shared is in telemedicine, wherein medical equipment manufacturers have an incentive to participate in these types of solutions. Smith pointed to the PPP presented earlier by Philips as an example of this use case.

In other use cases, Smith said the potential for a sustainable business model for the private sector is much less probable. National-level systems for collecting and aggregating data, Smith said, have the potential to monetize data, but the incentives are much weaker than the two previous use cases Smith described. These systems are often extremely expensive to roll out in low- and middle-income countries, he said, and require deploying hardware, establishing connectivity to facilities, training a workforce, maintaining software, and updating it over time. For these examples, Smith emphasized the importance of teasing apart use cases and evaluating the ones for which PPPs might really make sense.

Smith then addressed the issue of country context in determining the feasibility of digital health PPPs. Countries such as India, Kenya, and Nigeria are examples of places where there is a lot happening in digital health, and some scale is being achieved. Smith noted these countries have receptive environments for foreign multinational companies as well as robust local private sectors. However, he said, when you look at other countries, the environment for PPPs is very different. He pointed to the example of Ethiopia. The country has an impressive ability to mobilize resources in the public health system, but the private sector is weak. The limited private-sector environment is not conducive to PPPs.

Following Smith’s remarks, Stanton described recent action within the donor community for digital health to support more sustainable solutions. Stanton is a long-serving development professional who has only recently started working in the digital health space. He shared that as somebody who has worked in development for years, he was amazed when he learned about the appetite of individuals in LMICs to solve development problems through digital solutions. However, as he learned more, he discovered the sobering picture of fragmentation in the digital health ecosystem. Recently, donors have begun to recognize the consequences of uncoordinated and unsustainable investments in digital health.

Fortunately, there has been action to address this issue, Stanton shared, through the development of donor principles for digital devel-

opment, wherein a number of donors came together to collectively address how they can better and more sustainably support countries in advancing digital solutions. The donors started with the principles for digital development that were developed 8 years ago.2 These principles, Stanton explained, outline what a good digital system should look like and address issues regarding privacy and interoperability. However, the donors recognized that a missing component was a set of principles for how donors should interact with host governments.

The group developed a set of donor principles for digital development, and Stanton shared that the main principle is to start by supporting a national strategy. If a national strategy is not already in place, the donors pledge to invest in creating one. The logic for the focus on a national strategy stems from the donors’ realization that without an overarching, coordinating function at the national level, they are likely to repeat the same mistakes that had initially led to the state of fragmentation.

Stanton noted that the donor principles align with the USAID administrator’s principles for the agency. Of the five USAID principles, number one is to foster self-reliance, and number five is to protect the taxpayers’ investments. The donor principles fit within these principles, establishing a road map for more sustainable and efficient digital health investments.

Discussion

Esposito opened the discussion by noting how many of the technologies and models being implemented in digital health are new. Given this, what is needed in terms of evidence generation to prove their value and ability to scale? Oyedepo suggested digital health programs should be implemented with an iterative improvement strategy of learning quickly and adjusting along the way. Smith agreed and added that one of the big causes of handwringing in the digital health space has been the lack of an evidence base. There has been enormous excitement around the potential of these tools to improve health outcomes and to strengthen health systems, and next to that mountain of excitement, the actual evidence has looked a little bit like a molehill. He noted that the evidence base directly showing the effect that digital tools have on health system outputs and outcomes is quite thin. However, these tools are often implemented as part of a larger business process, and Smith wonders if it may be a bit self-defeating to try to isolate the effect of the introduction of the specific tool. He suggested more effort should be made to evaluate the effect of the larger set of changes in which the digital tool is being used. Stanton

___________________

2 To view the principles for digital development, see https://digitalprinciples.org/wpcontent/uploads/From_Principle_to_Practice_v5.pdf (accessed October 23, 2018).

added that evidence is vital for donors who need to show the effect of their investments. He feels a starting place would be to sit down with everyone involved from the outset to discuss metrics and time frames and go from there.

Esposito then asked the panelists how they think digital health strategies, PPPs, and donor funding differ depending on the economic status of a country where they are operating. Smith referred back to his earlier comment that PPPs will be dependent on how large and active the private sector is within a country. This factor, he feels, is more important than the overall level of economic development within the country. He has seen relatively low-resource countries implement successful PPPs by having an appropriate governance structure in place. Nigeria, the Philippines, and Rwanda are examples of countries that have built robust governance structures for their digital health architecture into which various solutions based on common standards can be plugged. The achievement of common standards by itself is a big incentive to the private sector to start participating in a sustained way because they need that predictability, Smith said.

To close the discussion, Esposito asked each panelist to give a final comment. Oyedepo stated that PPPs will work only when there is trust and respect. Smith remarked that as countries transition, the global health community needs to adjust its orientation and expectations for what the private sector’s role will be. The private sector may fill some gaps when donors leave, but expectations should be measured about what it will look like. Stanton commented that the global health community does not yet know what the role of the private sector will be in the next decade. As donors, there is a responsibility not to close any doors but to stay open to opportunities to achieve mutual goals through partnerships.

This page intentionally left blank.