In the workshop’s third session, four speakers offered their perspectives regarding the role of payers and providers in making current genetic testing methods more accessible across all populations. Sean Tunis, the founder and chief executive officer of the Center for Medical Technology Policy, emphasized the importance of focusing on public health priorities and areas where there is evidence of disparities in care and also identified ways in which genomic medicine could be helpful. Brian Ahmedani, the director of psychiatry research and a research scientist at the Center for Health Policy and Health Services Research at the Henry Ford Health System, shared his perspectives on how disparities in genomic medicine may affect those with mental health conditions. Katrina Armstrong, the physician-in-chief in the Department of Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), described approaches her institution uses to make genomic medicine equitable for all populations. Finally, Preeti Malani, the chief health officer at the University of Michigan and a professor of medicine at the University of Michigan Medical School discussed the importance of engaging with employers and their medical benefits advisory committees in the discussion around equity. An open discussion followed the presentations, moderated by S. Malia Fullerton, an associate professor of bioethics and humanities at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

FINDING WAYS FOR GENOMIC MEDICINE TO REDUCE EXISTING HEALTH CARE DISPARITIES

From the perspective of a policy maker and a payer, Tunis said, affordability is a key issue, and he noted that spending on publicly funded health care programs rose in the 2000s, while spending on all other categories of social services fell over the same period. In Massachusetts, for example, public expenditures on health care rose by $5 billion between 2001 and 2011, while social services spending fell by $4 billion. One could argue whether this is a cause-and-effect relationship, he said, but these data do

align with the notion that spending more public money on health care does limit how much money can be spent elsewhere. A key question for payers may not be how to reduce disparities in access to genomic medicine, he said, but rather how specific disparities in health care or health outcomes can be reduced with the application of genomic medicine. Framing the question in terms of how genomic medicine can reduce health care disparities will make it more likely that partnerships with payers and health systems will be successful, he said.

Concerning how payers think about reducing disparities and increasing access to services, Tunis said that they focus on three areas: coverage decisions, value-based payments, and population health. When deciding whether to cover a particular diagnostic service—genomic testing, in this case—Medicare requires that there be evidence showing that a new diagnostic approach is more accurate than existing technologies and that the evidence indicate how the test improves health outcomes (Deverka et al., 2016). Tunis suggested that an opportunity exists to collaborate with the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation on various types of outcome and quality measures demonstration projects related to disparities.

Value-based payment allows providers to decide if a new service will produce better outcomes at lower costs in exchange for taking on the added financial risk that comes with bundled or capitated payments. Value-based payment models could be a tool for reducing health care disparities, Tunis said, if the outcome and quality measures that relate to disparities can be included in the determination of value. He added that, in his opinion, population health is where the most emphasis should be placed in terms of engaging payers, health systems, and providers in reducing disparities in access to genomics.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality routinely publishes reports on health care quality and disparities related to the major causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States, Tunis noted. One way to potentially increase the level of interest in genomic medicine from payers and providers would be to identify ways in which genomic medicine could help reduce the disparities in the major causes of morbidity and mortality and then create quality- and value-based payment initiatives to incentivize applying genomic medicine to those areas, he said.

DISPARITIES IN ACCESS TO PRECISION MEDICINE: A VIEW FROM PSYCHIATRY

Precision medicine, Ahmedani said, is not solely about genetics or genomics. Rather, precision medicine focuses on the interaction of genetics and genomics with environmental exposures, patient preferences, the social determinants of health, and the various psychosocial factors that influence

whether genetic predisposition leads to a specific condition or disorder. The realization of precision medicine would allow for a better understanding of why some individuals develop a condition while others do not. The field of genomic medicine has made exciting advances already, he said, but in order to take the next step, it will be important to consider all of the environmental exposures as well.

While several of the previous talks at the workshop had been focused on cancer, Ahmedani’s presentation examined access to care for patients with mental health conditions. Twenty-five percent of the U.S. population will at some point in their lives meet the criteria for a having a mental disorder, he said. Mental health conditions, which have their own early genetic markers for increased risk, are important not only because of how common they are, but also because they happen to co-occur with virtually every other medical condition. In addition, Ahmedani said, the average time between when someone experiences symptoms of a mental disorder and when that person first gets care is 5 to 8 years, in large part because the very nature of a mental health condition can prevent a person from accessing care.

The Henry Ford Health System, located in southeast Michigan, is both a provider of care and an insurer, covering 15 to 20 percent of the Henry Ford patient population, Ahmedani said. The health system treats a large Medicaid and uninsured population as well as patients with commercial insurance. Due to its location in metropolitan Detroit, he said, the health system is well-versed in serving a diverse group of patients from a wide range of incomes, education levels, ethnic backgrounds, and ages. The Henry Ford Health System also recently became involved in the National Institutes of Health’s All of Us research program1 as the leader of one of the health care provider networks. Ahmedani is a co-principal investigator for the All of Us effort at Henry Ford, but he said he also looks at precision medicine through the lens of being a provider of care to patients with psychiatric conditions.

Sources of Disparities for Patients with Mental Health Conditions

Disparities can exist between those who have mental health conditions and those who do not, Ahmedani said. One area in which this takes place is insurance coverage. For example, in Michigan, the providers at Henry Ford often cannot treat a Medicaid beneficiary with a substance use disorder, but they must instead refer that individual to a community mental health facility, even though Henry Ford may have more resources to treat some of

___________________

1 Additional information about the All of Us research program can be found at https://allofus.nih.gov (accessed September 28, 2018).

these individuals. The extra work required to coordinate that individual’s care can create gaps in care and create more opportunities for people to fall through the cracks, he said. “If some payers cover precision medicine while others do not,” he said, “it will be extra work for providers to determine which patients are eligible, which can lead to no one or very few having access” to the care they need.

The stigma surrounding mental health conditions can also contribute to health care disparities between those with the mental health conditions and everyone else, Ahmedani said. Stigma can come from many different sources, including health care professionals who must make complex decisions about who will have access to certain treatments. During an evaluation, providers take into consideration whether the patient can comprehend precision medicine care and if it is likely if the patient will make it to his or her next appointment. Part of the stigma attached to mental health conditions is that they are often viewed as being behavioral rather than biological in nature. There are already mental health–related disparities in the way that care is provided, Ahmedani said, and these disparities will likely either not change or else get worse with the introduction of a new complex approach such as genomic medicine. Workforce shortages, staff turnover, limited appointment time slots, and long wait times plague care in some departments and settings. For example, it can take 3 months or more to get a psychiatry appointment, Ahmedani said, and well-resourced, private systems are more likely than public and community health systems to provide access sooner to genetic counselors.

Finding Solutions to Disparities

Precision medicine can potentially help ameliorate the problem of long wait times for a diagnosis and proper treatment by helping to identify a patient’s condition more quickly and to find the right treatment in a timely manner, Ahmedani said. There are genetic markers for most mental health conditions, he said, including for an increased risk of suicide and the likelihood of developing an addiction. One major problem in psychiatry is that it is often difficult to develop the most effective treatment plan for patients. If genomic medicine can shorten the time from diagnosis to a successful treatment plan, more people could have access to psychiatric services. In addition, Ahmedani said, identifying genomic markers and customizing treatments may lead to less stigma among medical professionals because it will help debunk the myth that behavioral conditions cannot be treated successfully.

Widespread insurance coverage of behavioral health conditions might lead to a greater uptake of genomic medicine into psychiatry, Ahmedani said. At the same time, if the application of genomic medicine to behav-

ioral disorders can increase the options for successful treatment, that could encourage more insurance companies to provide coverage for these disorders. Along those lines, he said, he thinks that the All of Us program and other precision medicine initiatives may have the greatest impact in areas where diseases are most stigmatized, such as for mental health conditions.

ENSURING THAT GENOMIC MEDICINE IS PROVIDED EQUITABLY

The field of medical genomics has come very far in the past two decades, Armstrong said, and there are genomic tests and strategies that are ready to be moved out of the genomics community and into the qualityimprovement2 and delivery world. For those tests and strategies that are not ready for widespread dissemination, she said, genomics researchers need to gather additional evidence on whether these tests and strategies will lead to better care so that institutions can decide whether to make them part of their accountability measures.

It is unacceptable that genetic testing in cancer is not more widespread and is not being delivered to patients equitably across the nation, Armstrong said. Armstrong described a study showing that African American women were significantly less likely to receive physician referrals for cancer genetic testing even after adjusting for family history, tumor stage and characteristics, comorbidities, socioeconomic factors, and attitudes about testing (McCarthy et al., 2016). It turns out, Armstrong said, that physicians had different rates of referral depending on the race of the women they saw. One possible contributor to that disparity is the lack of evidence about the utility of testing in African American women. “When we know something works, we need to figure out how to get the health care system to actually start delivering [those successes] equitably across groups,” Armstrong said.

When there is a tool that works, a disparity in the delivery of that tool is a quality problem, Armstrong said. Equity is a quality metric, and the focus of health care systems should be on improving quality by educating providers and patients about the value and utility of genomic medicine, on creating decision support tools for providers, on developing measurement and feedback processes, and on initiating targeted process improvement projects, she said. MGH has a Disparities Solution Center that leads efforts in this field, and the hospital holds Armstrong, as chief

___________________

2 The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) defines quality improvement as systematic and continuous actions that lead to measurable improvement in health care services and the health status of targeted patient groups. For more information, see https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/quality/toolbox/508pdfs/qualityimprovement.pdf (accessed August 22, 2018).

of medicine, accountable for reporting on a variety of measures aimed at reducing disparities in access to care.

The MGH Department of Medicine and Center for Genomic Medicine recently created the position of chief genomics officer, and this individual is in charge of directing efforts to determine who will order tests and manage the results and who will cover the cost of the test and assess if patients are comfortable with the service. One of the biggest genomics-related demands at MGH is for panel testing ordered by the specialty clinics, Armstrong said, and each clinic will have a lead genomics physician who manages the information and oversees the use of these tests, which are largely ordered for patients who are symptomatic. The bigger challenge is incorporating the predictive testing that takes place in primary care clinics, where patients are largely asymptomatic, into a population health strategy. This is a big challenge for primary care practices, Armstrong said, but it is something that primary care physicians are increasingly committed to achieving. MGH has developed a specialized service, called the Pathways service, that is using whole-exome testing for patients who have unexplained symptoms.

In the early days of genomic testing, providers were sending tests to many different commercial laboratories with no sense of which laboratories were producing high-quality results, Armstrong said. The strategy in the MGH Department of Medicine now is to have a list of internal and external laboratories that have been vetted for use by the staff and to have a genomics service with clinical geneticists and others who work with physicians and explain data that the physicians might need help navigating and understanding.

Hiring people who speak Spanish—along with the 31 other languages spoken by her institution’s patient population—is a major challenge in developing this paradigm. Armstrong said. Other challenges include ensuring continuity of care (i.e., making sure that people with limited resources can get to their follow-up visit) and ensuring that providers see the utility of genomic services for all their patients. The focus is now on guaranteeing that MGH’s efforts to develop this genomics service reach all of the communities that MGH serves and that they are not creating new disparities in access to care, she said.

Who Will Pay for the Tests?

Securing reimbursement for genomic tests can be extremely challenging, Armstrong said, citing a recent study that demonstrated the complex and rapidly changing landscape of payer rules for selected molecular genetic tests (Lennerz et al., 2016). In the United States, clinical outcomes and the source of insurance are strongly correlated, she said. Medicaid, which covers a large percentage of the low-income patients that MGH and other

institutions serve, is becoming almost entirely accountable care and managed care in most states. Therefore, Armstrong said, there is a critical opportunity for the genomics community to be at the table to discuss how these tests will be covered and to ensure that Medicaid populations are not excluded from this revolution in medicine.

Hospital administrators often are responsible for balancing budgets. With the rising costs of medicines and supplies, Armstrong said, it can be difficult to incorporate new technologies such as genomic medicine into the standard of care. She concluded by encouraging workshop participants to read the 2018 National Academies consensus study report Making Medicine Affordable: A National Imperative, which outlines many of the health care pricing issues she spoke about in greater detail (NASEM, 2018).

THE ROLE OF LARGE EMPLOYERS IN ADDRESSING DISPARITIES AND IMPROVING ACCESS TO CARE

Employers are important partners in the discussion about disparities in access to genomic medicine, Malani said, because approximately 50 percent of Americans receive health insurance through their employers. For adults under 65 years old who generally would not have Medicare, the percentage covered by their employers can be even higher. From the employer’s perspective, she said, healthy employees are productive employees, and helping employees stay healthy can yield big dividends down the line. “Employee wellness programs are not just nice things,” she said, “but they are important economically.”

At the University of Michigan, the availability of health insurance is equitable across all populations, but, as is the case at many employers, use is not, and there are differences in how the institution’s high-wage and low-wage workers access care. A study published in 2017 examined health care use and spending by wage category among nearly 43,000 employees at four large, self-insured employers (Sherman et al., 2017). After dividing the workers into five wage groups, with the lowest earning less than $24,000 per year and the highest earning more than $70,000 per year, the researchers found that low-wage workers used about half the amount of preventive care and had twice the hospital admission rate, four times the rate of avoidable admissions, and three times the rate of emergency department visits as the top wage earners.

At the University of Michigan, health care spending for employees earning less than $35,000 per year was slightly higher than for those earning more than $35,000 per year, but there were big differences in use, Malani said. Those earning less than $35,000 per year had lower spending on preventive care, mental health, and substance use visits and higher spending on emergency department visits and inpatient admissions than those earning

more than $35,000 per year. The insurance products were the same across the two wage groups, so insurance coverage was not a issue.

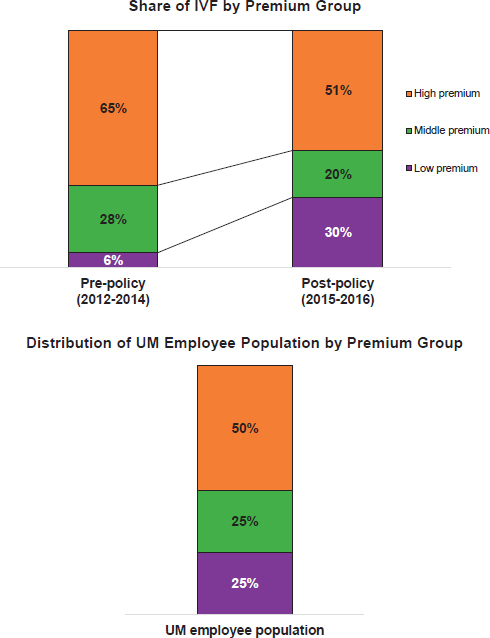

To address these disparities, the University of Michigan is beginning an employee health initiative that sends representatives into the communities where its employees live to provide wellness programs, such as cooking demonstrations with healthy food. “We are trying to build partnerships and hope we will be able to touch on more serious health issues as we build up that community,” Malani said. One question Malani still wanted to address was whether thoughtful health care benefit design could help address access and equity issues, and as a partial answer to that question she described the results of a 3-year trial conducted at the University of Michigan regarding in vitro fertilization (IVF) benefits.

After extensive discussion involving a wide range of internal and external experts, including clinicians, lawyers, bioethicists, and human resource personnel, the university established a set of rules to guide a trial benefit for IVF. The IVF pilot was limited to women who were 42 years old or younger and included a lifetime benefit set at $20,000, with coinsurance of 20 percent. By analyzing the data and assessing how many women underwent IVF before and after the pilot, it was clear that employees were taking advantage of this new benefit. Use increased the most in the lowest-income bracket (see Figure 4-1). “I get chills when I look at these data because when we talk about equity, this to me is equity,” Malani said. Today, in fact, women at all different income levels are equally likely to use this benefit. “I think it’s important to think about how you can do things creatively, sometimes, when you have control of the insurance, and in this case, the provider’s side,” she said, adding that, based on these results, the University of Michigan is likely to continue offering this benefit. If providing equity in genomic medicine is the goal, then employers and members of their medical benefits advisory committees should be key partners in the discussion, Malani said.

DISCUSSION

Implementing Equity Programs at Community Health Centers

Fullerton asked Armstrong if, in her opinion, a community health care system such as Denver Health could establish an approach that offers genomic tests routinely and equitably in the same way that MGH has done. FQHCs have many unique considerations, Armstrong answered, and Medicaid policy largely drives what is available at FQHCs, including those at Denver Health. One of the challenges with Medicaid is that the money is not always being spent on interventions that are forward thinking, she added. “We need to be at the table to figure out how to influence Medicaid

NOTE: IVF = in vitro fertilization; UM = University of Michigan.

SOURCES: Preeti Malani, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine workshop presentation, June 27, 2018. Figure is courtesy of James Dupree, University of Michigan.

policy,” she said. As Medicaid moves to accountable care organizations, the challenge will be to work with different partners, including the community, to control costs in other areas so that these types of services can be offered. It will be important to have a support system in place to help patients navigate these new areas of care and better coordinate care, Ahmedani added. One opportunity could be shifting thoughts about how care is provided, he said, and focusing on low-intensity interventions and coordinated care sooner to avoid high-intensity interventions that may require more staffing and resources later.

Alternate Payment Models: Coverage with Evidence Development

One approach to paying for new precision medicine technologies involves coverage with evidence development (CED)—a system where insurers pay for certain technologies and services for which the evidence is not considered adequate, but pay for them in the context of carrying out additional research. There are many advantages to CED, Tunis said, but it does have its limitations, including the issue of performing additional post-coverage studies. Even as helpful as CED is, Tunis said, it still does not solve the problem of how to allocate resources to include new tests or other technologies.

Making the Case for Implementing Genomics in Health Systems

“What were the arguments that convinced the [MGH] health system to invest in the infrastructure and make this change?” asked a workshop participant. Making the case to health system leadership is not a one-time discussion, Armstrong said. In the process of implementing new practices, such as genomics, there are certain budget considerations and tradeoffs that need to be made. Providers should be making space for genetic services in their health care budgets, Armstrong said. “Prevention and investment in precision medicine is the future,” she said, “and we need to get ahead of the curve in [making the case].” Joan Scott, the director of the Services for Children with Special Health Needs division at HRSA, asked Armstrong how incorporating applications in the clinic can be done as a form of quality improvement in genetic medicine. Armstrong said that one of the most obvious ways to do this would be to create cross-fund efforts for genomics and quality improvement.

This page intentionally left blank.