3

Setting the Stage

The workshop’s second panel, as well as a separate presentation later in the workshop, provided background information on behavioral health and mental health disorders, on the communication challenges that these disorders create for individuals and family members, and on the principles of health literacy and how health literacy might address some of those communication challenges. The speakers who addressed these topics were Wilson Compton, the deputy director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA); David Steffens, a professor and the chair of psychiatry at the University of Connecticut Health Center; Michael Wolf, a professor and the associate vice chair for research in the Department of Medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine; and Catina O’Leary, the president and chief executive officer of Health Literacy Media. A discussion was moderated by Steven Rush, the director of the UnitedHealth Group Health Literacy Innovations Program.

DEFINING MENTAL HEALTH AND BEHAVIORAL HEALTH: WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE?1

After agreeing with the comments of the last session that training in communication issues for health care providers is “woefully inadequate,” Wilson Compton said he hoped this workshop would generate some action-

___________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Wilson Compton, the deputy director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

able items to address that issue, whether during training, through continuing education, or through system-level approaches that would influence behavior, such as Yelp-like reviews or financial incentives. He added that incentives and rewards do not have to be large to change behavior, something that research at NIDA has shown.

Commenting on what he heard in the first session, Compton said he was impressed by how much stress can impede good communication, and he added that while individuals with a mental illness may have a particular problem with stress, those without a mental illness can have similar issues. For example, someone who has just received a cancer diagnosis may be very stressed and unlikely to remember much of what else the physician says from that point forward. “While we are focusing on mental illness and mental health issues today, some of these issues are generic across all the health literacy field,” he said, adding that he hoped that the lessons from other areas of health and could be applied to the area of behavioral health. Another lesson he took from the first panel’s presentations was that health care providers might need some instruction on basic etiquette. “I was impressed that an awful lot of what was missing was just basic kindness and basic respect,” Compton said.

Turning to the subject at hand, he explained that behavioral health is a global term used as shorthand for a broad range of conditions and that, like all shorthand, it has severe limitations in that it does not provide the nuance or detail needed to make complex care decisions. To him, he said, behavioral health includes mental illness as well as substance abuse and addictive disorders. He added that topics such as medication adherence, which is a behavioral issue, are related subjects but are not generally included in the term “behavioral health.” Because behavioral health is such an overarching label, it is important to define the term, particularly in publications. “We may not agree on what the boundaries are around it, but if you define it, I can at least accept what you mean when you use that term,” said Compton.

Behavioral health issues are extremely common, he noted, with some 46 percent of Americans meeting the criteria for a diagnosable mental or substance use disorder at some point in their lives. The annual prevalence of a mental health issue is 18 percent, Compton said, with some 4 percent of Americans meeting the criteria for a serious mental illness over the past year and 8.1 percent meeting the criteria for a substance use disorder. Approximately half of all mental disorders begin before age 14, and 75 percent first appear before age 24.

Comorbidity is common as well, he said, with some 8.2 million adults having both a substance abuse disorder and a mental illness. “One of the key issues for taking care of patients with these conditions is that when you discover one of them, you need to very carefully explore for other disorders,” Compton said. Too often, physicians forget to ask their patients

with major depression or schizophrenia about their alcohol or tobacco use. “Just by paying attention to comorbidity, we can improve care,” he said.

While mental illness may be a more specific term, it, too, includes a broad category of disorders—autism and autism spectrum disorders, childhood behavioral conditions such as conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder, Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in older adults, and major mental illnesses such as depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. “Each one of those deserves some separate attention and some nuance,” Compton said, “so I remind us that even as we think in these broad categories we need to pay attention as well to the individual needs within each of those diagnostic groups, because while there will be a few similarities, there will be nuances in terms of the specific disorder.” The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) defines a mental disorder as “a syndrome characterized by clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental processes underlying mental functioning.” Mental disorders, he added, are usually associated with significant distress in social, occupational, or other important activities.

Substance use disorders, he explained, occur when the recurring use of alcohol or drugs causes clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems, disability, and a failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home. According to the DSM-5, a diagnosis of substance use disorder is based on evidence of impaired self-control, social impairment, the risky use of alcohol or drugs, and certain pharmacological criteria. Compton said that substance use disorders follow a particular development course and have multiple causes, which include environmental and biological contributors.

Compton pointed out that a key feature of many mental illnesses and substance use disorders is disordered thinking and that this can impede communication in a direct manner. “You have somebody who, because of their brain condition, just cannot hear what you are saying,” Compton said. In addition, behavioral health patients can display behaviors that they are unable to control, further getting in the way of good communication. This communication impediment exists over and above any impairments that result from the stress of the clinical experience, he added. Stigma also impedes communication, both directly and indirectly, and it affects patients, families, and even clinicians. In the addiction field, stigma exists among policy makers and in the criminal justice system, and as such, notations of a substance use disorder in an EHR can become an impediment for those seeking care. While Compton agreed that it is important to integrate care, he said that it is also important to recognize the potential for such integration to backfire in some circumstances.

One place where stigma is playing out today is in the nation’s response to the opioid epidemic, Compton said. Despite the fact that there are proven, medication-based treatments for opioid addiction that can help people improve their functioning, regain their lives, and become pro-social, active members of society who are not breaking the law or putting their own lives at risk, too few people have access to these treatments because there are not enough clinicians in many parts of the country who can provide care. Even where treatment programs exist, only about one in four such programs will offer medication-assisted treatment (Knudsen et al., 2011). “I think that is because of some of the internal stigma that medication-assisted treatment faces within the treatment providers themselves,” Compton said. He did applaud the change in philosophy toward medication that has been adopted by programs such as Betty Ford and Hazelden, stalwarts of 12-step approaches to addiction, when shown the data that their patients were unsuccessful when not offered medication and that they were not continued on medication in the longer term.

Concerning approaches to address these issues, Compton said he believes it is possible to change attitudes, reduce stigma, and tailor communication to patients with behavioral health and mental health disorders. For example, clinical programs that participated in research on buprenorphine, one of the medications used to treat opioid use disorder, were more likely to adopt medical treatment in their programs going forward. “The ability to practice with [buprenorphine] was useful for long-term change,” he said. It is important to change providers’ attitudes toward medication-assisted therapy because research has shown that provider attitudes about the effectiveness of this approach and its morality affect whether the therapy is offered and used (Bailey et al., 2013; Uebelacker et al., 2016). Compton noted that he has seen attitudinal changes over the past few years that are bringing more of a public health and population health focus—rather than a purely law enforcement issue—to the issue of opioid addiction.

There are ways of reducing stigma through the use of language, he said. For example, referring to an individual as “a substance abuser” rather than “having a substance use disorder” can bias clinician attitudes about whether these individuals are culpable, threatening, or deserving of punishment (Kelly and Westerhoff, 2010). Compton concluded his presentation by highlighting what the U.S. Surgeon General had to say about substance use disorders, which was that everyone has a role to play in changing the conversation around substance use in order to improve the health, safety, and well-being of individuals and communities across the nation. “I think the work of this roundtable on communication issues fits in nicely with what the Surgeon General highlighted,” Compton said. Although the Surgeon

General was speaking specifically about substance use disorders, Compton said he believes that this message applies more broadly to all behavioral health conditions.

HOW COGNITIVE BURDEN AFFECTS COMMUNICATION2

To begin his presentation, David Steffens reported that when the University of Connecticut Health Center worked with EHR vendor Epic on the design of its new system, it made the strategic decision to make all of its psychiatric notes available to other physicians in the system. There was debate within the psychiatry department involving concerns about stigma, but in the end the decision was made to open the record as far as symptoms, course of treatment, and medications. “I think the field is moving to be much more integrated,” he said.

“When it comes to cognitive concerns,” Steffens said, this is not an issue just about primary cognitive disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias or mild cognitive impairment. People with acute medical issues, such as heart attack and pneumonia, as well as with chronic disorders such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sleep apnea, and Parkinson’s disease, may have cognitive problems as well. These cognitive impairments, which are under-recognized in the medical community, can affect both an individual’s level of function and his or her ability to communicate effectively.

From a neuropsychological perspective, cognition refers to memory, attention and concentration, information processing, visuospatial perception, language abilities, and executive function—the ability to reason, plan, problem solve, and multitask among other actions—with memory, attention and concentration, information processing, and executive function being the most relevant to mental illness. Steffens said the signs and symptoms of executive dysfunction include trouble grasping the main idea of something, struggling to weigh benefits and risks, general difficulty making decisions, problems holding onto a several-step mental process, trouble initiating lists or making new goals, and a lack of flexibility. Executive function control resides in the brain’s frontal lobes, the same brain region involved in a wide variety of mental illnesses and substance use disorders (Arnsten and Rubia, 2012). Steffens said that executive dysfunction, which can persist despite improvements in other psychiatric symptoms, can make it difficult for people to comprehend complex verbal or written communication and to weigh one choice against another.

___________________

2 This section is based on the presentation by David Steffens, a professor and the chair of psychiatry at the University of Connecticut Health Center, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Steffens explained that the capacity for communicating and making decisions about health care has four dimensions, each of which can be affected by executive dysfunction (Palmer and Harmell, 2016):

- understanding the nature as well as the risks and benefits of treatments and alternatives;

- appreciating and applying the relevant information to one’s self and one’s own situation;

- engaging in consequential and comparative reasoning and manipulating information rationally; and

- expressing a clear and consistent decision.

Memory problems can be present in disorders other than dementias, Steffens said. The hippocampus is the key brain region involved in memory formation and retrieval, but the temporal and frontal lobes play important roles as well. The signs and symptoms of memory problems include difficulty learning, storing, retaining, and retrieving information. Older adults, he said, may have early dementia with memory problems that are masked by the presence of depression or anxiety, and people with traumatic brain injury can also have memory problems. Steffens noted that of the four dimensions of capacity for communicating and making decisions about health care, memory problems can affect the ability to understand the nature as well as the risks and benefits of treatments and the ability to express clear and consistent decisions.

Attention and concentration, which together refer to the ability to stay awake and alert, maintain focus, and hold onto a train of thought, can also be affected in individuals with a mental illness. The brain structures involved in attention and concentration include the posterior parietal lobe and the frontal lobe, Steffens said, and attention and concentration problems are often present in depression, mania, psychoses, anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and attention deficit and attention deficit–hyperactivity disorders. He explained that the signs and symptoms of attention and concentration problems include difficulty staying alert as a result of not having enough mental energy to fully engage with people or things in the environment; difficulty focusing attention and being easily distracted by external or internal stimuli; and losing a train of thought or forgetting the point in a conversation. Of the four dimensions of capacity for communicating and making decisions about health care, impairment in attention or concentration may affect understanding, reasoning, and expression of choice.

Information processing, the fourth aspect of cognition that comes into play in mental illnesses, refers to the ability to take in environmen-

tal stimulation through the five senses, interpret it, and respond to it. Information processing, Steffens said, relies on cortical and subcortical connections in the brain, and it is a fairly typical symptom in those with moderate to severe depression. The signs and symptoms of slowed information processing include slowed thinking speed and response times, the tendency to absorb only fragments of information, and social inappropriateness resulting from difficulty interpreting and making sense of social cues and the body language of others. Of the four dimensions of capacity for communicating and making decisions about health care, slowed information processing can affect understanding and reasoning, he said.

Steffens said that it is striking how many of the people with depression that he sees demonstrate poor understanding of important concepts. A person with depression, he said, can parrot back words on a consent form without really demonstrating any effort or the ability to put what they read into their own words. Similarly, manic patients may understand in general what their illness is and how much treatment can help the symptoms, but they may not have much insight into why that information applies to them. This causes difficulties in collaborative health care decision making. Impaired reasoning comes into play when a person with schizophrenia articulates a decision to refuse antipsychotic medication, not because of a concern about side effects but out of a delusional belief that the drug is a poison. Steffens explained that people with severe anxiety and depression may be so overwhelmed that they cannot decide or express a choice. “If the goal is collaborative care with the patient, these can be frustrating for all concerned,” Steffens said. “Knowing that part of the underlying condition that somebody has may actually impair their abilities is important.” He added that while this is something he tries to teach medical students and residents, ultimately it takes experiencing these issues to understand how to deal with them in practice.

In thinking about ways that one can improve health care communication and decision making concerning mental illness, Steffens said that while treating the underlying condition can be helpful, this may be a catch-22 situation because the discussion may be about treatment options. “If you can come to some agreement about the best way to get the anxiety and depression level down, that can be helpful,” he said. Some studies of cognitive remediation and cognitive training have shown them to be helpful at improving executive function and memory (Best and Bowie, 2017; Best et al., 2019), and recent research suggests that neurostimulation may help alleviate some of the underlying cognitive disorders that are part of mental illness (Francis et al., 2018).

HEALTH LITERACY, COGNITIVE BURDEN, AND HEALTH CARE3

To set the stage for his presentation, Michael Wolf set forth four assumptions he would be making. The first assumption, supported by multiple studies, was that a person’s cognitive skills are a major determinant of health literacy skills (O’Conor et al., 2015; Wolf et al., 2012). “When you think about everything you need to do to engage in health care and how we envision and define health literacy, it absolutely relies heavily on cognition,” he said. Second, the heath literacy skills needed to successfully manage health are determined by the design and accessibility of a health care system and the demands those place on the individual. Third, reducing cognitive burden entails communicating better, simplifying patient roles by changing workflows and processes, and having a proactive learning health care system that works to understand patients better and uses data to act on that understanding. Fourth, addressing cognitive burden alone will not remedy all existing health literacy concerns.

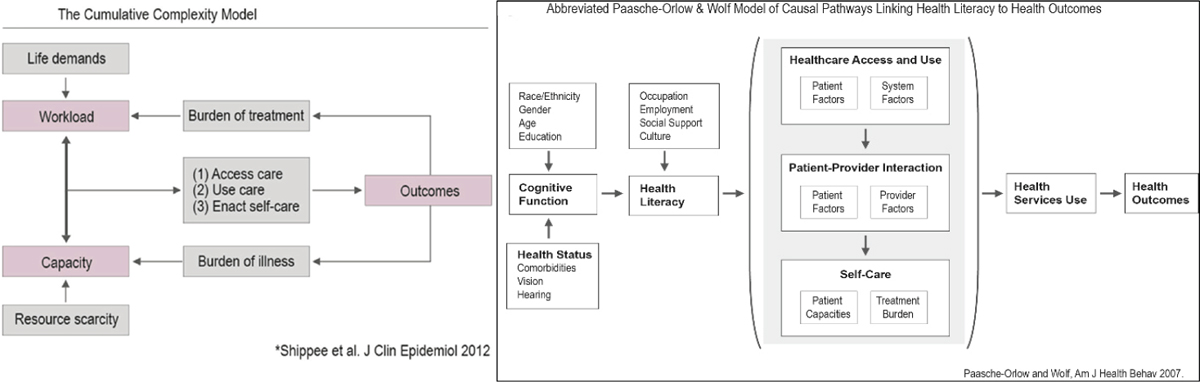

To help think about cognitive burden and its link to health literacy, Wolf offered a conceptual framework (see Figure 3-1) that merges a cumulative complexity model developed by Victor Montori and colleagues at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota (Shippee et al., 2012), and a model he and Michael Paasche-Orlow developed that links health literacy and health outcomes (Paasche-Orlow and Wolf, 2007). These two frameworks use different language to get at the notion of treatment burden, the capacity of the patient, and the workload placed on someone by being a patient and taking on the many roles required by the health care system and by whatever illnesses they have. Wolf reported that for the past decade he and his collaborators have been following a cohort of more than 900 patients and tracking their cognitive performance (Serper et al., 2014; Wolf et al., 2012). His team has found a strong correlation between cognition and many of the most common measures of health literacy and have determined that the ability to perform literacy tasks is strongly dependent on an individual’s depression, anxiety, and overall mental health.

The concept of cognitive burden, or what some call cognitive load, relates to the intrinsic and extrinsic factors that create barriers to the performance of a range of health care tasks, Wolf explained. Wolf commented on how hard it can be to manage the self-care tasks and activities of daily life in the face of disease and treatment burden. As an example, Wolf said, many patients now have to navigate technologically advanced medical equipment that physicians believe will help them without the technologi-

___________________

3 This section is based on the presentation by Michael Wolf, a professor and the associate vice chair for research in the Department of Medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

SOURCES: As presented by Michael Wolf at the workshop The Intersection of Behavioral Health, Mental Health, and Health Literacy on July 11, 2018; Paasche-Orlow and Wolf, 2007; Shippee et al., 2012.

cal literacy needed to use these devices, something that is sure to increase cognitive load. Monitoring care responsibilities and reading through health insurance fine print can also increase cognitive burden, as can reading and understanding the health information a patient receives (Wilson and Wolf, 2009; Wilson et al., 2010). Wolf added that inappropriate imagery—pictures that look nice but provide no useful information—can also create unnecessary cognitive load.

There are three take-away messages from this work, Wolf said. The first is that disparities in patient outcomes among patients with low health literacy are evidence that a health care system is creating excess cognitive burden for its patients, which is a sign that the health care system has more work to do to ensure that it not only recognizes but also meets the needs of its diverse population.

A second take-away is that universal precautions are insufficient for helping all patients and families access, navigate, use, and benefit from health care. Without a mechanism for identifying the most vulnerable patients, including those who may be feel stigmatized by the fact that they do not comprehend information very well, and then having approaches to connect with those individuals, a health care system is likely to be less inviting than it could be to those individuals. “Finding ways to identify people who may be missed by universal precautions is important,” Wolf said.

While it is important to continually work at improving all forms of health care system communications in order to meet health literacy best practices, Wolf said, health systems need to appreciate that a one-size solution will not meet the needs of all patients and that reducing cognitive burden may not benefit the 20 percent of patients who are cognitively compromised. For example, it is possible to reduce the cognitive load of print health information for individuals with marginal health literacy but not for those with low health literacy. In addition, the evidence supporting the effectiveness of interventions optimizing multimedia and spoken health information is limited. Research has shown that the greatest successes in improving behavioral and clinical outcomes have come from interactive, multifaceted problem-solving-based interventions for self-management (Schaffler et al., 2018).

Wolf emphasized that he is not against universal precautions. Rather, he said, he believes that health care systems should take advantage of the strong evidence base for how to develop better, more comprehensible materials that meet all patients’ needs. Even after reducing the cognitive burden of materials, for example, some patients will need help by some other means, perhaps because they have a mild cognitive impairment or undiagnosed mild dementia. Wolf suggested that there may be different health literacy types, each needing a different approach.

His final take-aways from his research are that the number one health literacy goal should be to reduce the cognitive burden of health information and that the overall health system goal should be to reduce treatment burden. “This is about getting a health care system to think more about how it is providing care to patients,” Wolf said, adding that this is a bigger issue for quality improvement, into which health literacy has to tie.

As a final thought, Wolf asked whether health systems should consider developing a screen to identify low-health-literate individuals. By identifying those patients, it might then be possible to schedule more time for them with their physicians and to look at their treatment plans and medications to see if those are increasing the cognitive burden they experience. He asked, too, if there might be some way to ensure that family members and caregivers are getting all of the information they need in a form they can understand. These are significant issues, he said in closing. “As we get older, we naturally develop multiple morbidities, and we have more and more issues that fall onto our place and create greater self-management demands at the same time that we see a natural age-related decline in cognitive ability.”

HEALTH LITERACY PRINCIPLES IN MENTAL AND BEHAVIORAL HEALTH4

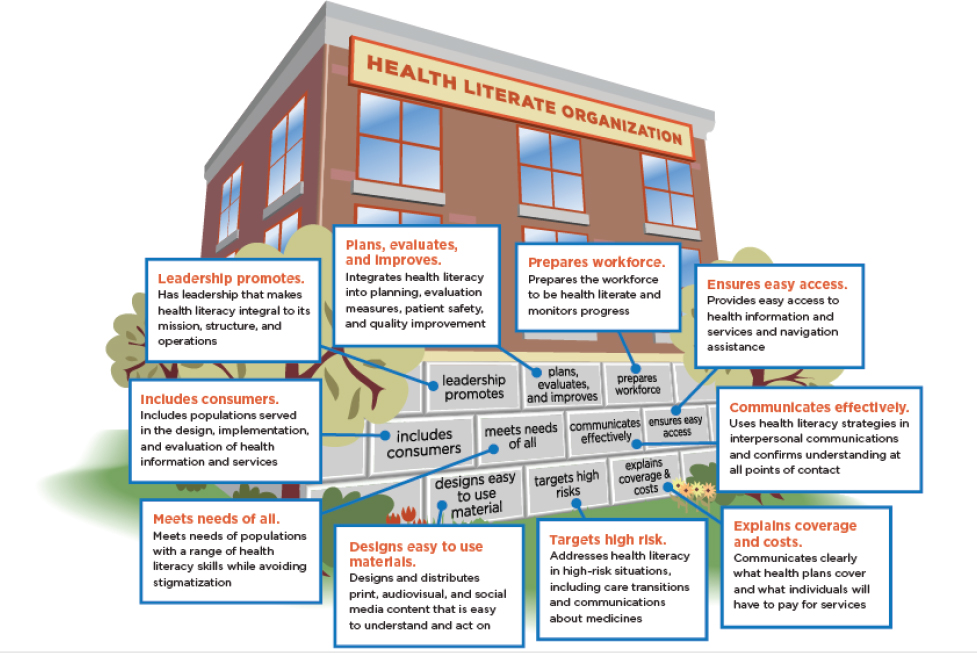

One of the most important ways to enable shared decision making and patient-centered, integrative, collaborative care and to meet people in their communities, including social online communities, is via a health-literate organization (see Figure 3-2), Catina O’Leary said. She added that she was impressed by the fact that the day’s speakers, most of whom do not work in the health literacy field, had been using the language of health literacy in discussing their work.

What the speakers had not commented on, she said, is that approximately 57 percent of adults with a mental illness go untreated in the United States, a figure that reaches 70 percent in some states. “They are out there sort of navigating the world,” O’Leary said. Even when these individuals present with physical ailments, their mental health conditions often go untreated, which likely contributes to the fact that people with a serious mental illness die an average of 25 years earlier than those without a mental health condition. People with serious mental illnesses, she said, are more likely to die from cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and related conditions such as kidney failure, respiratory diseases including pneumonia and influenza, and infectious diseases, including HIV/AIDS.

___________________

4 This section is based on the presentation by Catina O’Leary, the president and chief executive officer of Health Literacy Media, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

SOURCES: As presented by Catina O’Leary at the workshop The Intersection of Behavioral Health, Mental Health, and Health Literacy on July 11, 2018; Brach et al., 2012.

Mental illness, O’Leary said, makes it more likely that an individual will experience problems accessing health care because of such system factors as fragmentation and a lack of coordinated care. Another issue is that behavioral health providers, who are “trained communicators,” are not versed in the principles of health literacy, she said. Furthermore, other medical professionals have competing demands and limited time for patient encounters, as well as inadequate training on how to communicate with patients and families about mental illness. In addition, as a result of their mental health conditions, individuals with a mental illness often lack motivation, are fearful of their encounters with the health care system, and suffer from social instability. The symptoms of their illnesses can render them unable to seek care or to speak about their problems with their health care provider. O’Leary said that health care systems could learn from schools about ways of increasing the functionality of health systems for patients with special challenges—for example, by providing additional time with providers for patients with complex mental health conditions and other communication challenges.

Echoing previous speakers, O’Leary said that stigma among providers is a threat to access and effective communication. Stigma, she said, leads

to such problems in patients as poor adherence to medication regimens, dropping out of treatment programs, skipping appointments with providers, delayed treatment for physical ailments, and an overall lack of physical care. “I do not think we spend enough time thinking about how what we do as providers increases problems and keeps people from getting care,” O’Leary said. Increased paranoia and anxiety, decreased attention and concentration, superstition, and auditory hallucinations are also barriers to effective communication between patient and provider, she said, as is a history of actual or perceived trauma from past experiences with the health care system.

O’Leary explained that individuals with a mental health issue report that doctors assume they are not reliable witnesses to their own health care, that they are being rushed through their appointments with their providers, and that their providers are not truly listening to their issues. Patients report that at least some providers treat them as if their brains are broken and that they cannot possibly comprehend information relevant to their conditions. Often, answers to questions are terse and gloss over some of the most important medication risks, particularly when a patient is prescribed multiple drugs. O’Leary said providers should keep in mind that communication with anyone is a dynamic process where understanding is not always guaranteed and that they need to look for signs that their patients are not grasping important information.

Fortunately, she said, evidence exists that health literacy strategies can work with individuals with mental health issues. Four techniques from health literacy—conducting a health environment assessment, using plain language in written materials and when speaking, developing symptom-based communication strategies, and displaying empathy, humanness, and kindness—are particularly useful with this population. Based on the Integrated Behavioral Health Project’s Interagency Toolkit, O’Leary suggested several steps that providers can take to reduce barriers to communicating with their patients with a mental illness and to creating a safe and welcoming environment for them (IBHP, 2013):

- Give a patient 2 minutes to talk before interrupting.

- Explain the illness, its importance, and its potential impact on life using words the patient can understand.

- Provide written information prepared in language the patient can understand.

- Explain medications and address patient concerns.

- Do not assume the patient’s symptoms are all in his or her head.

- Link treatment to the patient’s recovery goals.

- Offer and encourage participation in peer support groups.

- See the patient as a whole person, not as a person with a condition.

Switching gears, O’Leary discussed a project that she and her team conducted in partnership with the Truman Medical Centers, the largest provider of mental health services in the Kansas City metropolitan area. Her team’s role was to deliver four training sessions on health-literate communication skills. “We had all of these behavioral health providers who did not really have any prior knowledge of verbal communications or written communications and all the sort of standard interventions we do,” O’Leary said. She and her team also conducted health environment assessments at 5 of Truman Medical Centers’ behavioral health facilities, reviewed and revised 56 pages of existing patient-facing documents, and wrote and designed 96 pages of new client education materials using plain language principles.

“The cool thing about how we created these new ones, though, is we went into their meetings where they were doing case management, and we talked about the problems and the questions that they get over and over again and try to answer on the spot,” O’Leary said. As a result, her team created materials that would enable the care staff to answer those questions with factually correct, health-literate, and accessible information. “They could speak the answer, but then they could also support it. That is really important in facilities like this where there is a lot of turnover and a lot of lower-educated staff, that is, staff who do not have a lot of behavioral health training or experience,” she explained. “Retraining people over and over again on materials that are outside their skill set is not really a workable solution.”

The health environment assessments revealed that patients were having navigation issues, and that the stress of being lost in the health care system could negatively influence a patient’s mental health, functional ability, and safety. The researchers also found that poorly designed facilities were reinforcing negative behaviors, promoting self-injury, and increasing some patient’s compulsive and obsessive tendencies. In addition, the materials that patients were receiving were unclear or irrelevant to their conditions, contributing to stigma and negatively affecting how they understood their illnesses.

For individuals with a mental illness, using plain language is a “very big deal,” O’Leary said. Health care providers often use medical jargon that is unfamiliar to most people, and the educational materials they give their patients are often written at a level beyond their patients’ ability to understand. Materials, she explained, need to be easy to read and understand and to be visually appealing. She said that in addition to redesigning materials, she and her team taught managers and key staff how to identify, revise, and write documents using health literacy principles so that they could prepare these materials without outside help. One thing her team did was to create templates and train staff how to use them to make updates to existing materials and develop new materials. “This is a low-cost way to empower staff and make sure that they always have what they need,” O’Leary said.

She concluded her presentation with some additional suggestions for practitioners and policy makers. At the national level, O’Leary suggested designating people with serious mental illness as a population that experiences health disparities. She also recommended adopting ongoing surveillance methods and supporting education and advocacy. At the state level, she said, it is imperative to improve access to physical health care, promote coordinated and integrated mental health and physical health care for people with serious mental illnesses, and provide funding to support these two initiatives.

For provider agencies and clinicians, O’Leary recommended adopting a policy that integrates mental health and physical health, helps patients and staff understand the message of recovery, and implements care coordination models. She also recommended encouraging the people that the health care system serves, including families and communities, to develop and share their vision of integrated care, and for the health care system to encourage families and the communities they serve to be advocates, educate themselves, and participate in partnerships with the health care system. Finally, she recommended that patients and families pursue individualized, person-centered care focused on recovery and wellness.

Concerning how the health literacy community can embrace the mental health field, she said it is important to recognize the relationship between mental health and health literacy. Individuals with low health literacy, she said, tend to have poor health status, use emergency rooms more frequently, and have a higher death rate—problems that are multiplied for those with mental illness. She also called on the health literacy community to work with mental health systems to integrate health literacy into daily practice by training medical staff on communication strategies to increase patient understanding, educating those who develop health-related documents to use plain language practices, and assessing health systems for their health literacy and helping them apply targeted health literacy best practices to address identified shortcomings.

DISCUSSION

Michael Paasche-Orlow from the Boston University School of Medicine started the discussion by saying he did not understand Wolf’s misgivings about universal precautions as a means of identifying someone who is having trouble understanding medical information. He noted that universal precaution is not a single method but rather an approach to identify who is struggling to succeed in the care context. “Then, by finding those people, you have to identify what the interventions needed are going to be, and then you identify the sub-phenotypes,” he said. Wolf replied that his concern is that universal precautions are being applied variably and superficially. “I think without a process in place where we can do a better job of kind

of characterizing what the nature of the issue is, we may lead to a more superficial remediation of the patient until you really understand it,” he said. He explained that his worry is that a universal precautions approach is likely to miss the individual who has been experiencing subtle cognitive decline over many years. He said he would like to see a way developed of characterizing each patient and having a detailed map on what to do about a specific health literacy phenotype.

Cindy Brach from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) agreed with Wolf about the importance of identifying vulnerable patients so that clinicians can spend more time with them, and she asked Wolf if he had an idea of what the algorithms might look like for identifying those patients ahead of their appointments. Wolf did not have an answer, but he said that the geriatrics division at his institution has been working on developing such an algorithm using data from a patient’s EHR, such as the time spent at previous visits, if the patient has multiple morbidities, and if there is suspected cognitive impairment. He noted that his practice is rolling out a two-step cognitive impairment detection protocol that might serve as a first alert that a person might need more time for an appointment.

Steffens said that he hopes such an approach could be expanded to populations of people with chronic and persistent mental illness. While it is generally assumed that common issues of executive dysfunction affect cognition, he said, it would be nice to move beyond making assumptions. “I wonder whether we can be informed by what we know from cognitively impaired older populations and apply that to younger populations with mental illness,” he said. “I think this is an understudied and underequipped area and one that I would encourage the roundtable to continue to think about because we want to be able to detect these issues and then hopefully design interventions that will actually help people take more ownership of their health care decision making.” Compton added that some of this will require additional research and clinical trials and asked if the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation or the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute might be likely sources of funds for such studies.

Terry Davis from the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center asked the panelists for their opinions about technology and telemedicine. Steffens replied that there is a growing consensus that tele-psychiatry can be helpful. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has been one of the innovators in this field, and a number of demonstration projects are being conducted by other health systems as well. Compton said that it is important to remember the limitations and lack of applicability of technology to important sub-segments of the populations. “I would encourage us to focus on a population perspective,” he said. “Are we impacting a large enough group that it is worth investing in these sometimes complex technologies to apply across broad areas?” Compton noted that while the VHA has learned

how to do telemedicine, there are regulatory as well as practical issues, such as which provider in a practice will do the telemedical calls. Compton said that he would like to see technology deployed to monitor drug levels and smoking behavior, for example. “I would love to know when my patients are drinking, smoking cigarettes, or using other substances,” he said.

Wolf said that the health literacy field could increase its efforts to make sure that user interfaces are compelling and that they have been developed following health literacy principles. He commented on the importance of testing these interfaces in the target audiences to forestall the possibility that the interfaces would drive disparities. He also pointed out that it can take a substantial investment in time to introduce users to a new technology platform. He then reported that he and Paasche-Orlow have been testing a method of leveraging interactive voice recognition technology and that, so far, they have not observed any disparities by literacy level. “In fact,” he said, “I would say we have shown incredible uptake. People are wanting to be more connected to their clinic beyond the point of care because they are not getting what they need during the visit.” Wolf added that the key for the successful adoption of a new technology is to make sure it is well-designed and to then demonstrate that it is effective.

Nicole Holland from the Tufts University School of Dental Medicine asked Compton if there is any evidence yet that changing terminology—from “substance abuse” to “substance use disorder,” for example—has any effect on stigma. Compton replied that scrubbing the language of potentially stigmatizing words will be an ongoing process and that it will not be done quickly. Ellen Markman commented that changing the terminology from “substance abuse” to “substance use disorder” is likely to have an effect on health care providers as well as the general public. Compton agreed and said that the idea behind the terminology change was to make language more person-centered. He added that changing language is a challenge because old habits die hard. He also noted that this change in terminology has been controversial in the addiction policy world because some people would like to see stigma increased as a way of emphasizing the antisocial nature of substance use. Paasche-Orlow added that there is a stigma around low literacy as well, something he has seen in his research. And he reported that the medical students at his institution are all using “substance use disorder” and not talking about “abuse” anymore.

Olayinka Shiyanbola from the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy asked Compton if the lack of access to medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorders has resulted from too few places offering it or too few providers who can prescribe it and, if it is the latter, whether pharmacists could augment the workforce. Compton replied that the literature suggests that the reason is both a lack of providers and bias against the treatment itself among some addiction service providers them-

selves. He said that NIDA would be open to research projects looking at having other providers, such as pharmacists, become involved in this area. In fact, NIDA recently funded a small pilot study for pharmacists to dispense methadone, he said, noting that the bureaucratic hurdles to launching the program were “significant” because of the required Drug Enforcement Administration registrations. “What sounds like a good idea and is used in other countries may require either legislative action to implement in this country or a major shift in the regulatory environment,” he said.

Brach added that SAMHSA requires providers of medication-assisted treatment to receive special training and to be approved by the agency and that not many providers are interested in pursuing that time-consuming licensing. Compton pointed out that Congress passed legislation several years ago that expanded the ability of nurse practitioners and physician assistants to dispense medication-assisted treatments. Steffens said another barrier is reimbursement, depending on whether an individual is privately insured or on Medicaid.

Christopher Dezii asked Wolf if his work suggests that people in the lowest cognitive capabilities group have the poorest outcomes and highest cost. Wolf said that the answer is yes, with individuals who are cognitively impaired and who also are of low health literacy having the worst outcomes. Patients fall across the entire gradient, he said, with outcomes depending on both cognitive capabilities and health literacy. For example, he said, those with cognitive impairment and adequate health literacy have outcomes similar to those with normal cognitive capabilities and low health literacy.

Jennifer Dillaha from the Arkansas Department of Health recounted the horror she felt one day when she realized that a patient she had seen several times had a cognitive impairment that she had not detected in previous appointments; she said it was similar to the horror she felt when she realized she was seeing patients with low health literacy who were walking out of the appointments and going out into the waiting room and asking their daughter or son to explain what she had just said. “Both of these, to me, have something to do with how we design the clinical appointment and who they see and interact with besides just the doctor,” she said.

Wolf responded that this is a big issue and that he has been working on one project whose goal is to find out how to identify those individuals who have some cognitive impairment within the structure of the workflow. It has been challenging at his institution to figure out a way in a fee-for-service or relative value units system to find space to insert a 30- or 40-minute appointment with a patient. One approach might be to use technology to extend visits beyond the point of care and to allow patients to report in through various means, although this would require expanding the bandwidth of the clinic to take in this new information. He said that his

institution has a federally qualified health center and that it has made this approach work through a great deal of effort. Steffens added that there are models using technology to administer a cognitive screen, such as a medical assistant, or to interview the relative who accompanies a person to the appointment. “There are models out there and assessments out there that potentially could be implemented that would trigger further investigation by the provider, but systems have to figure this out,” Steffens said. “All that screening does not have to take place at the provider level, which is maybe more cost intensive, and there are some things that can be done by well-trained ancillary staff.”

Compton remarked that there is a need to step back and conduct more formative work regarding health literacy and self-management of care in the population of people with a mental or behavioral health disorder. “We have made an assumption that it needs to be externally provided and externally managed, and that is in error,” he said. The question that needs answering, he said, is how to take the principles of health literacy and apply them in a mental health or addiction clinic or a fully integrated clinic caring for these patients with multiple morbidities.

Davis noted that the Kahn Academy, which offers online videos to help kids master new school subjects, has figured out how to use technology to reduce the cognitive burden for children who have difficulty learning certain subjects, and she asked if researchers are developing similar approaches to help reduce the cognitive burden of patients and families. Wolf said that there are many examples in the health literacy evidence base showing that there are ways of reducing cognitive burden in the health care setting, and that technology plays a role in some of these approaches.

REFERENCES

Arnsten, A. F., and K. Rubia. 2012. Neurobiological circuits regulating attention, cognitive control, motivation, and emotion: Disruptions in neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 51(4):356–367.

Bailey, G. L., D. S. Herman, and M. D. Stein. 2013. Perceived relapse risk and desire for medication assisted treatment among persons seeking inpatient opiate detoxification. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 45(3):302–305.

Best, M. W., and C. R. Bowie. 2017. A review of cognitive remediation approaches for schizophrenia: From top-down to bottom-up, brain training to psychotherapy. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 17(7):713–723.

Best, M. W., D. Gale, T. Tran, M. K. Haque, and C. R. Bowie. 2019. Brief executive function training for individuals with severe mental illness: Effects on EEG synchronization and executive functioning. Schizophrenia Research 203:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j. schres.2017.08.052.

Brach, C., D. Keller, L. M. Hernandez, C. Baur, R. Parker, B. Dreyer, P. Schyve, A. J. Lemerise, and D. Schillinger. 2012. Ten attributes of health literate health care organizations. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/BPH_Ten_HLit_Attributes.pdf (accessed August 14, 2018).

Francis, M. M., T. A. Hummer, J. L. Vohs, M. G. Yung, A. C. Visco, N. F. Mehdiyoun, T. C. Kulig, M. Um, Z. Yang, M. Motamed, E. Liffick, Y. Zhang, and A. Breier. 2018. Cognitive effects of bilateral high frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in early phase psychosis: A pilot study. Brain Imaging and Behavior May 31. doi: 10.1007/s11682-018-9902-4. [Epub ahead of print.]

IBHP (Integrated Behavioral Health Project). 2013. IBHP interagency collaboration tool kit. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/operations-administration/IBHP_Interagency_Collaboration_Tool_Kit_2013.pdf (accessed September 12, 2018).

Kelly, J. F., and C. M. Westerhoff. 2010. Does it matter how we refer to individuals with substance-related conditions?: A randomized study of two commonly used terms. International Journal of Drug Policy 21(3):202–207.

Knudsen, H. K., A. J. Abraham, and P. M. Roman. 2011. Adoption and implementation of medications in addiction treatment programs. Journal of Addiction Medicine 5(1):21–27.

O’Conor, R., M. S. Wolf, S. G. Smith, M. Martynenko, D. P. Vicencio, M. Sano, J. P. Wisnivesky, and A. D. Federman. 2015. Health literacy, cognitive function, proper use, and adherence to inhaled asthma controller medications among older adults with asthma. Chest 147(5):1307–1315.

Paasche-Orlow, M. K., and M. S. Wolf. 2007. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. American Journal of Health Behavior 31(Suppl 1):S19–S26.

Palmer, B. W., and A. L. Harmell. 2016. Assessment of healthcare decision-making capacity. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 31(6):530–540.

Schaffler, J., K. Leung, S. Tremblay, L. Merdsoy, E. Belzile, A. Lambrou, and S. D. Lambert. 2018. The effectiveness of self-management interventions for individuals with low health literacy and/or low income: A descriptive systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine 33(4):510–523.

Serper, M., R. E. Patzer, L. M. Curtis, S. G. Smith, R. O’Conor, D. W. Baker, and M. S. Wolf. 2014. Health literacy, cognitive ability, and functional health status among older adults. Health Services Research 49(4):1249–1267.

Shippee, N. D., N. D. Shah, C. R. May, F. S. Mair, and V. M. Montori. 2012. Cumulative complexity: A functional, patient-centered model of patient complexity can improve research and practice. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 65(10):1041–1051.

Uebelacker, L. A., G. Bailey, D. Herman, B. Anderson, and M. Stein. 2016. Patients’ beliefs about medications are associated with stated preference for methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone, or no medication-assisted therapy following inpatient opioid detoxification. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 66:48–53.

Wilson, E. A., and M. S. Wolf. 2009. Working memory and the design of health materials: A cognitive factors perspective. Patient Education and Counseling 74(3):318–322.

Wilson, E. A., D. C. Park, L. M. Curtis, K. A. Cameron, M. L. Clayman, G. Makoul, K. Vom Eigen, and M. S. Wolf. 2010. Media and memory: The efficacy of video and print materials for promoting patient education about asthma. Patient Education and Counseling 80(3):393–398.

Wolf, M. S., L. M. Curtis, E. A. Wilson, W. Revelle, K. R. Waite, S. G. Smith, S. Weintraub, B. Borosh, D. N. Rapp, D. C. Park, I. C. Deary, and D. W. Baker. 2012. Literacy, cognitive function, and health: Results of the LitCog study. Journal of General Internal Medicine 27(10):1300–1307.