4

Medications for Opioid Use Disorder in Various Treatment Settings

Medication-based treatment is effective across all treatment settings studied to date. Withholding or failing to have available all classes of U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved medication for the treatment of opioid use disorder in any care or criminal justice setting is denying appropriate medical treatment.

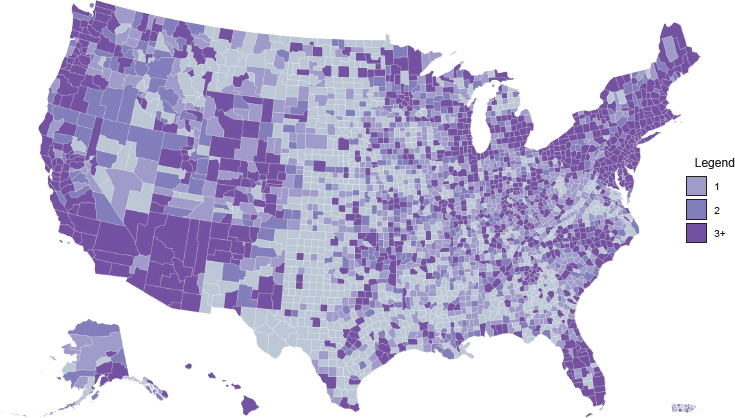

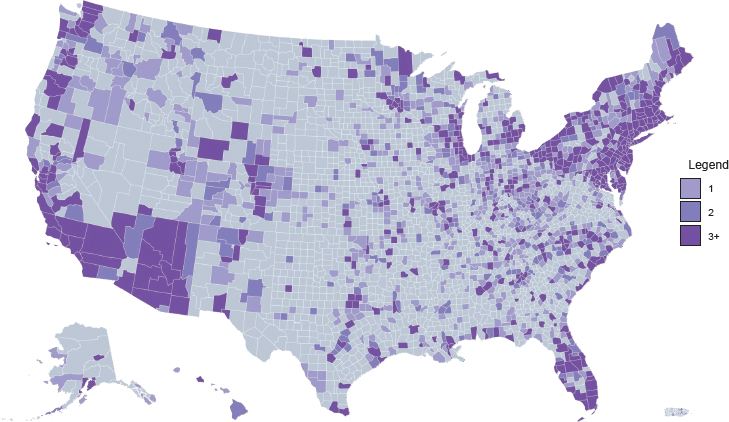

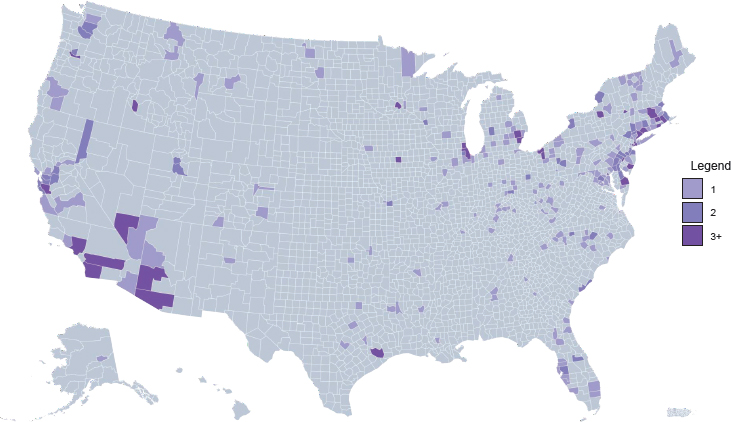

Access to medications for treating opioid use disorder (OUD) is highly variable across different types of treatment settings. Figure 4-1 shows the density of substance use disorder (SUD) treatment facilities by county in the United States.1 Although overall roughly 36 percent of SUD treatment facilities offer medication to patients (see Figure 4-2), only about 6 percent provide patients with a choice of all three U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications (amfAR, 2018; Mojtabai et al., 2019) (see Figure 4-3). This chapter reviews the evidence on differences in medication access and use in different treatment settings and, to the extent that it is available, any scientific rationale underpinning those differences.

OPIOID TREATMENT PROGRAMS

The Narcotic Addict Treatment Act of 19742 requires that methadone be administered to patients only through federally certified and regulated opioid treatment programs (OTPs), commonly referred to as methadone clinics. OTPs were originally created to provide methadone treatment, but today many of them also provide other medications for OUD. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) began certifying OTPs in 2001, and between 2003 and 2015, the number of patients enrolled in methadone treatment increased by 57 percent.3 After the introduction of buprenorphine in 2002, the number of OTPs offering buprenorphine increased from 11 percent (121 OTPs) in 2003 to 58 percent (779 OTPs) in 2015. The number of OTPs that offer extended-release naltrexone also grew from 11 percent of the total (125 OTPs) in 2011 to 23 percent (315 OTPs) in 2015 (Alderks, 2017).

All OTPs must be certified by SAMHSA and registered by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Before certification, an OTP must first be evaluated in a peer-review process by a SAMHSA-approved accrediting organization, which conducts site visits and reviews the facility’s policies, procedures, and practices. Even after accreditation, an OTP is not formally certified to administer methadone until SAMHSA has determined that the OTP conforms with federal regulations regarding patient admission criteria, recordkeeping guidelines, and required services, such as counseling and testing for drug use. After certification, the OTP must also apply separately for registration with the DEA, which has requirements around security,

___________________

1 Darker areas on the maps indicate a greater number of facilities (light purple = one facility; medium purple = two facilities; dark purple = three or more facilities). Note that counties differ in size—those in the Southwest tend to be much larger in area than counties in the Northeast, for example—and this may affect the interpretation of the maps.

2 Public Law 93-281 (1974).

3 This increase appears to stem from an increase in OTPs combined with better identification of OTPs in the National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services survey (Alderks, 2017).

NOTE: Gray = no facilities; light purple = one facility; medium purple = two facilities; dark purple = three or more facilities.

SOURCE: amfAR, 2018.

NOTE: Gray = no facilities; light purple = one facility; medium purple = two facilities; dark purple = three or more facilities.

SOURCE: amfAR, 2018.

NOTE: Gray = no facilities; light purple = one facility; medium purple = two facilities; dark purple = three or more facilities.

SOURCE: amfAR, 2018.

inventory, and recordkeeping. An OTP’s registration from the DEA must be renewed on an annual basis (GAO, 2016). The regulations also require that most patients attend the clinic nearly every day to receive their doses of medication, which is an attempt to reduce diversion. See Chapter 5 for a detailed discussion on how some of the regulations around methadone are a barrier to treatment.

OFFICE-BASED OPIOID TREATMENT

Expanding the delivery of medications for OUD through medical office–based treatment settings has been a strategy for increasing access to medications for OUD (see Box 4-1). Currently, naltrexone can be prescribed by any physician, nurse practitioner (NP), or physician assistant (PA) within a scope of practice. In contrast, the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 20004 stipulates that buprenorphine can only be prescribed by providers with additional DEA certification, unless they are working in an OTP setting. Moreover, to qualify for a waiver from the DEA to prescribe buprenorphine, federal law

___________________

4 See 21 U.S.C. § 823(g)(2).

requires that physicians take an 8-hour course and that NPs and PAs complete 24 hours of training. In addition, the number of patients that providers are allowed to treat is restricted. Specialist physicians are allowed to treat up to 100 patients in the first year and 275 patients thereafter, provided they have a waiver and meet additional criteria (e.g., board certification in addiction medicine or psychiatry), while NPs and PAs can treat no more than 100 patients each (SAMHSA, 2016, 2018a,b).

A systematic review of studies that assessed different primary care and specialty care models for delivering medication-based treatment for OUD did not reach any strong conclusions regarding which specific delivery models led to better patient outcomes (Lagisetty et al., 2017). However, the review did note that studies in which the treatment was successful, with high treatment retention and good-quality care measures, tended to use multidisciplinary care (i.e., specialty addiction services integrated with primary care) or coordinated care (i.e., physicians supported by care management).

In the United States, medications for treating OUD are typically delivered through high-threshold, low-tolerance models that require patients to comply with a number of strict requirements, such as frequent urine testing and weekly counseling sessions, in order to receive treatment. A patient’s response in the first month of treatment is often predictive of longer-term response (Weiss and Rao, 2017). For example, patients who submit drug-positive urine specimens or miss their appointments early in treatment are usually associated with poorer outcomes. However, it has been argued that these requirements can have counterproductive effects on treatment outcomes (McElrath, 2018) and that lower-threshold models, which do not place additional requirements on individuals trying to access medication-based treatment, hold promise in lowering the bar for entry into treatment (Socias et al., 2018). Individualized treatment using measurement-based care can help support patients during the early stages of treatment. This involves repeatedly measuring variables and adapting treatment in response to a patient’s progress or lack thereof. While this practice is widely used throughout medicine, it is used infrequently in the treatment of SUDs, including OUD (Trivedi and Daly, 2007).

Community health centers (CHCs) can also play an important role in improving access to OUD treatment among people who are medically underserved. A survey of CHCs found that many had expanded their OUD treatment services to respond to the escalating epidemic. Almost half of all CHCs offered at least one medication for OUD, and nearly two-thirds of the CHCs providing medication-based treatment offered at least two of the three FDA-approved medications. Buprenorphine, the most commonly prescribed medication for opioid withdrawal, was available at 87 percent of CHCs that provided any medication for OUD (Zur et al., 2018). How-

ever, many CHCs face ongoing challenges related to insufficient treatment capacity—63 percent reported that they did not have the capacity to treat all of their patients with OUD, and 68 percent of centers reported shortages of referral providers (Zur et al., 2018).

ACUTE CARE SETTINGS

The number of people treated for opioid-related conditions, including opioid overdose, in emergency departments and hospitals in the United States has increased substantially in recent years. Between the third quarter of 2016 and the third quarter of 2017, the number of emergency department visits for opioid overdoses increased almost 30 percent, according to data captured through the National Syndromic Surveillance Program of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Vivolo-Kantor et al., 2018). Furthermore, people with OUD are overrepresented in the population of hospitalized patients compared with their prevalence in the general population (Peterson et al., 2018). Therefore, acute care settings provide opportunities to intervene with patients who have OUD. Even though most providers in emergency departments and hospitals are not waivered to prescribe buprenorphine, non-waivered providers are permitted to administer buprenorphine or methadone to patients under their care for other medical reasons.5

Various studies indicate that effective medication-based treatment for OUD can be initiated in acute care settings and that patients can be successfully transferred to outpatient medication-based treatment after hospital discharge. The emergency department visit is a chance to treat people with OUD for withdrawal symptoms with medication and to bridge those patients to longer-term medication-based treatment plans (Chamberlin et al., 2018). For example, in one recent study, buprenorphine treatment initiated in the emergency department was associated with improved short-term treatment engagement and decreased illicit opioid use (D’Onofrio et al., 2015). In a randomized trial of hospitalized patients with OUD, patients who received an intervention that included induction, stabilization, and transitioning to long-term outpatient buprenorphine treatment had improved linkage to treatment after they were discharged compared with patients who received only a 5-day buprenorphine taper (Liebschutz et al., 2014). Although initiating treatment with methadone or buprenorphine in the hospital represents an important opportunity to engage patients in longer-term care, the rates of linkage to treatment after patients are discharged have been low (Naeger et al., 2016; Rosenthal and Goradia, 2017; Trowbridge et al., 2017). In one study, only 28 percent of opioid overdose

___________________

5 Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000). See 21 U.S.C. § 823(g)(2).

survivors seen in an emergency department or hospital were afterward linked to medication-based treatment for OUD (Larochelle et al., 2018).

OTHER CARE SETTINGS

Other care settings that could provide or enable access to medication-based treatment for OUD include residential facilities, nursing homes, outpatient facilities, supportive housing, and homeless shelters. More than 500,000 people with OUD in 2016 entered these care settings,6 many of which focus primarily on “cold turkey” detoxification and impose a zero-tolerance policy for opioid use of any kind—with no exception for evidence-based medications like methadone and buprenorphine. The continued popularity of treatment settings that ban or discourage medication persists despite the lack of evidence for this approach and the known potential for harmful effects (NARR, 2018). Return-to-use rates following medically supervised withdrawal (also known as “detox”) have been reported to be as high as 65 to 91 percent; this approach also carries a high risk of overdose due to a reduced tolerance for opioids if patients return to use (Broers et al., 2000; Chutuape et al., 2001). Many funding streams for these facilities are tied to the criminal justice system or housing authorities, creating strong incentives to steer patients toward non-medication-based treatment approaches (Andersen and Kallestrup, 2018).

CRIMINAL JUSTICE SETTINGS

While OUD is highly prevalent in criminal justice settings in the United States, few justice-involved individuals can access medication-based treatment while in jail or prison. In addition, justice settings rarely have systems in place to transition individuals with OUD to medication-based treatment at the time of release. More than half of the people in U.S. prisons have a diagnosis of SUD with or without co-occurring serious mental illness,7 with the rate of OUD in jails and prisons estimated to be around 15 percent (Baillargeon et al., 2009; James and Glaze, 2006; Peters et al., 1998).

___________________

6 Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Treatment Episode Data Set.

7 People with OUD in criminal justice settings often have co-occurring psychiatric disorders, they tend to have high rates of infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C virus, and they often face complex challenges related to emotional, physical, social, and financial issues (Brochu et al., 1999). Although criminal justice populations tend to be male, increasing numbers of women are entering the system. Many of these women face even more severe issues than their male counterparts in terms of social, financial, emotional, and medical obstacles, which are compounded by an increased likelihood of a history of abuse (Langan and Pelissier, 2001).

A 2007–2009 summary from the Bureau of Justice Statistics indicated that 58 percent of state prisoners and 63 percent of sentenced jail inmates met the criteria for a SUD, versus around 5 percent of the total adult population in the country (Bronson et al., 2017). However, only around 28 percent of prisoners and 22 percent of jail inmates participated in a drug treatment program (Bronson et al., 2017). Using 2014 National Treatment Episode Data Set data, Krawczyk and colleagues examined the use of methadone and buprenorphine treatment among people referred through the judicial system to specialty treatment for OUD; only 4.6 percent of justice-referred clients received either medication (Krawczyk et al., 2017). A survey of 51 prison systems across the country found great variation by state, but, overall, most corrections systems do not offer any medication to incarcerated individuals with OUD, nor do they provide referral to treatment upon release (Nunn et al., 2009). Methadone was available in about half of the systems surveyed, but around half of those facilities limited methadone treatment to pregnant women or for chronic pain management; only 14 percent of systems provided buprenorphine. Few prison systems offered all three medications as treatment options for OUD (Nunn et al., 2009).

For people with OUD involved with the criminal justice system, a lack of access to medication-based treatment leads to a greater risk of returning to use and overdose after they are released from incarceration (Chandler et al., 2016). People with a history of OUD have a demonstrably high risk of mortality following release from incarceration. One study found an all-cause mortality rate of 737 per 100,000 person-years among former prisoners, with opioids related to almost 15 percent of all deaths (Binswanger et al., 2013). In a randomized trial of participants already receiving methadone treatment at arrest, those who were forced to withdraw from methadone were less likely to resume methadone treatment after release (Rich et al., 2015). Another retrospective cohort analysis examined the implementation of a comprehensive medication-based treatment program in the Rhode Island corrections systems. Results indicated a 60.5 percent reduction in the proportion of all overdose deaths of people who had recently been incarcerated following release, relative to the proportion of overdose deaths in the period before the program was initiated (Green et al., 2018). Randomized trials have also compared the outcomes of people who initiate methadone treatment prior to release from incarceration versus those who were referred to treatment upon release. Participants who initiated treatment while incarcerated were more likely to engage in treatment after release, and they reported less illicit drug use after 6 months (McKenzie et al., 2012). A recent meta-analysis of experimental and quasi-experimental studies examining provision of medications for OUD in correctional settings found that methadone significantly improved engagement in treatment postrelease, reduced illicit use, and

use by injection; however, reductions in recidivism were not consistently observed (Moore et al., 2019), likely due to state differences in probation and parole, among others. The authors noted too few experimental studies involving buprenorphine (n = 3) and naltrexone (n = 3) to perform meta-analysis of the data for these outcomes. Nevertheless, critical review of the individual studies indicated that buprenorphine and naltrexone were either superior to placebo or to methadone, or were comparable to methadone in reducing illicit use postrelease (Moore et al., 2019). Researchers at three study sites in the Studies on Medications for Addiction Treatment in Correctional Settings collaborative are pooling data from randomized effectiveness trials comparing extended-release naltrexone to methadone with enhanced treatment among people with OUD who are incarcerated; they are also looking at the benefits of a patient navigation program when added to medication (Chandler et al., 2016). Given their impact on mortality, it has been argued that withholding medications for OUD during incarceration is unethical, as would be withholding insulin or blood pressure medication (Bruce and Schleifer, 2008).

Civil commitment is not incarceration, but its alignment with the court system creates important considerations related to people with OUD and their access to medication-based treatment. The practice of civil commitment for opioid use is a legal provision that permits a judge to mandate opioid treatment (typically to an inpatient setting) for individuals whose opioid use poses a high likelihood of serious harm to self or to others, such as overdose, incapacitation, or other substantial danger (Christopher et al., 2015). A majority of U.S. states permit civil commitment for SUDs, and the use of civil commitments has been increasing in recent years (Cavaiola and Dolan, 2016). Like other criminal justice practices involving people with OUD, civil commitment procedures typically do not involve the provision of medication-based treatment, and research demonstrates high rates both of return to use and of overdose postcommitment under these practices. Postcommitment remission rates can be improved by a number of factors, including postcommitment medication-based treatment (Christopher et al., 2018).

According to one study, 56 percent of drug courts refer to treatment programs that offer at least one type of medication for OUD (Matusow et al., 2013). However, many of those programs require that medications be used only for tapering or as a bridge to completely stopping opioid use of any kind, including methadone or buprenorphine; this is not consistent with the evidence base for the most effective treatment strategy for OUD. A number of recent studies have found support for the use of injectable naltrexone in criminal justice settings. Despite the high discontinuation rates for injectable naltrexone, it may be more acceptable to judges and other correctional officials than methadone or buprenorphine (Lee et al.,

2015, 2016; Lincoln et al., 2018). Notably, when all three FDA-approved medications are available, only a small number of incarcerated patients select naltrexone (Green et al., 2018).

INNOVATIVE SETTINGS FOR OUD TREATMENT

Expanding treatment to settings outside of the medical and specialty addiction sectors has the potential to increase treatment access for traditionally hard-to-reach and socially disenfranchised populations. A broader definition of treatment settings may be necessary to connect people with medications in those populations, which include people who have never previously engaged in treatment, people who inject drugs, people who have severe OUD, people who are homeless, people who have recently been released from jails or prisons, and people who have other conditions that may make it challenging to access treatment (Hall et al., 2014). Examples of innovative treatment settings include

- mobile medication units to provide medication-based treatment directly to people’s homes or communities (Gordon et al., 2017; Torrens et al., 2013);

- group-based treatment to homeless individuals (Doorley et al., 2017);

- treatment within syringe exchange programs (Bachhuber et al., 2018; Fox et al., 2015; Kuo et al., 2003);

- physician–pharmacist collaborative models (DiPaula and Menachery, 2015); and

- low-threshold “transitions clinics” or methadone linkage programs for people recently released from jail or prison (Fox et al., 2014; Rich et al., 2005).

The “hub and spoke” model, which involves collaborative care provided through coordinated treatment across OTPs to office-based outpatient treatment, offers another innovative approach to improved care integration (Brooklyn and Sigmon, 2017). Although new treatment strategies are emerging for connecting hard-to-reach populations with OUD to medication-based treatment, few of these have been rigorously tested.

Low-Barrier Medication-Based Treatment

Policies and protocols that create more accessible medication-based treatment are generally referred to as low-barrier medication-based treatment. Emerging research suggests that there are a range of benefits associated with low-barrier approaches to providing medications for OUD. Such

approaches include interim methadone dosing, which is the provision of methadone medication to patients who are not yet fully enrolled into a comprehensive methadone program (Schwartz et al., 2011), and buprenorphine home induction protocols (Bhatraju et al., 2017; Cunningham et al., 2011; Gunderson et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2009). Other new low-barrier approaches are novel models with promising evidence of benefits such as successful naloxone distribution and improved uptake of medication-based treatment. For instance, one study carried out in the fentanyl-affected city of Vancouver used a modified mobile trailer located near an emergency department to provide a post-overdose care alternative, documenting a substantial number of medication-based treatment inductions on site (Scheuermeyer et al., 2018). Research in these areas is needed to better meet the needs of more patients and to quantify the benefit, risk, and cost-effectiveness of these approaches to medication-based treatment delivery.

Technological Tools

The incorporation of electronic health records (EHRs) into many treatment systems can be leveraged to support research and to better understand proficiencies in clinical services related to the provision of medication-based treatment for OUD. Clinical dashboards that are populated from EHR systems provide real-time actionable data, for example, which would be highly valuable for the treatment of OUD. In a recent review of the use of clinical dashboards, Dowding and colleagues concluded that clinicians’ immediate access to information can improve adherence to quality standards and help improve patient outcomes (Dowding et al., 2015; Patterson Silver Wolf, 2018). While technology advancements in behavioral health hold promise in the treatment of OUD, these tools need to be underpinned by a sound body of evidence assessing their impact on the access, quality, and cost of OUD treatment services from well-controlled randomized clinical trials (Ramsey, 2015). Telemedicine represents another potential opportunity to reach patients in underserved areas as well as to link providers who are inexperienced in treating OUD with mentors (Huhn and Dunn, 2017; Weintraub et al., 2018).

REFERENCES

Alderks, C. E. 2017. Trends in the use of methadone, buprenorphine, and extended-release naltrexone at substance abuse treatment facilities: 2003–2015 (update). https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/report_3192/ShortReport-3192.html (accessed February 12, 2019).

amfAR (The Foundation for AIDS Research). 2018. National opioid epidemic: Facilities providing substance abuse services. http://opioid.amfar.org/indicator/SA_fac (accessed January 15, 2019).

Andersen, K. J., and C. M. Kallestrup. 2018. Rejected by A. A. The New Republic, June 27.

ASAM (American Society of Addiction Medicine). 2005. Public policy statement on office-based opioid agonist treatment (OBOT). https://www.asam.org/advocacy/find-a-policy-statement/view-policy-statement/public-policy-statements/2011/12/15/office-based-opioidagonist-treatment-(obot) (accessed February 12, 2019).

Bachhuber, M. A., C. Thompson, A. Prybylowski, J. Benitez, S. Mazzella, and D. Barclay. 2018. Description and outcomes of a buprenorphine maintenance treatment program integrated within Prevention Point Philadelphia, an urban syringe exchange program. Substance Abuse 39(2):167–172.

Baillargeon, J., T. P. Giordano, J. D. Rich, Z. H. Wu, K. Wells, B. H. Pollock, and D. P. Paar. 2009. Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA 301(8):848–857.

Bhatraju, E. P., E. Grossman, B. Tofighi, J. McNeely, D. DiRocco, M. Flannery, A. Garment, K. Goldfeld, M. N. Gourevitch, and J. D. Lee. 2017. Public sector low threshold office-based buprenorphine treatment: Outcomes at year 7. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice 12(1):7.

Binswanger, I. A., P. J. Blatchford, S. R. Mueller, and M. F. Stern. 2013. Mortality after prison release: Opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Annals of Internal Medicine 159(9):592–600.

Brochu, S., L. Guyon, and L. Desjardins. 1999. Comparative profiles of addicted adult populations in rehabilitation and correctional services. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 16(2):173–182.

Broers, B., F. Giner, P. Dumont, and A. Mino. 2000. Inpatient opiate detoxification in Geneva: Follow-up at 1 and 6 months. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 58(1–2):85–92.

Bronson, J., J. Stroop, S. Zimmer, and M. Berzofsky. 2017. Drug use, dependence, and abuse among state prisoners and jail inmates, 2007–2009. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Brooklyn, J. R., and S. C. Sigmon. 2017. Vermont hub-and-spoke model of care for opioid use disorder: Development, implementation, and impact. Journal of Addiction Medicine 11(4):286–292.

Bruce, R. D., and R. A. Schleifer. 2008. Ethical and human rights imperatives to ensure medication-assisted treatment for opioid dependence in prisons and pre-trial detention. International Journal on Drug Policy 19(1):17–23.

Cavaiola, A. A., and D. Dolan. 2016. Considerations in civil commitment of individuals with substance use disorders. Substance Abuse 37(1):181–187.

Chamberlin, M., A. Herring, J. Luftig, M. Glenn. 2018. Treating opioid withdrawal in the ED with buprenorphine: A bridge to recovery. https://www.aliem.com/2018/05/treating-opioid-withdrawal-buprenorphine (accessed January 3, 2019).

Chandler, R. K., M. S. Finger, D. Farabee, R. P. Schwartz, T. Condon, L. J. Dunlap, G. A. Zarkin, K. McCollister, R. D. McDonald, E. Laska, D. Bennett, S. M. Kelly, M. Hillhouse, S. G. Mitchell, K. E. O’Grady, and J. D. Lee. 2016. The SOMATICS collaborative: Introduction to a National Institute on Drug Abuse cooperative study of pharmacotherapy for opioid treatment in criminal justice settings. Contemporary Clinical Trials 48:166–172.

Christopher, P. P., D. A. Pinals, T. Stayton, K. Sanders, and L. Blumberg. 2015. Nature and utilization of civil commitment for substance abuse in the United States. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law 43(3):313–320.

Christopher, P. P., B. Anderson, and M. D. Stein. 2018. Civil commitment experiences among opioid users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 193:137–141.

Chutuape, M. A., D. R. Jasinski, M. I. Fingerhood, and M. L. Stitzer. 2001. One-, three-, and six-month outcomes after brief inpatient opioid detoxification. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 27(1):19–44.

Cunningham, C. O., A. Giovanniello, X. Li, H. V. Kunins, R. J. Roose, and N. L. Sohler. 2011. A comparison of buprenorphine induction strategies: Patient-centered home-based inductions versus standard-of-care office-based inductions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 40(4):349–356.

DiPaula, B. A., and E. Menachery. 2015. Physician–pharmacist collaborative care model for buprenorphine-maintained opioid-dependent patients. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 55(2):187–192.

D’Onofrio, G., P. G. O’Connor, M. V. Pantalon, M. C. Chawarski, S. H. Busch, P. H. Owens, S. L. Bernstein, and D. A. Fiellin. 2015. Emergency department–initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 313(16):1636–1644.

Doorley, S. L., C. J. Ho, E. Echeverria, C. Preston, H. Ngo, A. Kamal, and C. O. Cunningham. 2017. Buprenorphine shared medical appointments for the treatment of opioid dependence in a homeless clinic. Substance Abuse 38(1):26–30.

Dowding, D., R. Randell, P. Gardner, G. Fitzpatrick, P. Dykes, J. Favela, S. Hamer, Z. Whitewood-Moores, N. Hardiker, E. Borycki, and L. Currie. 2015. Dashboards for improving patient care: Review of the literature. International Journal of Medical Informatics 84(2):87–100.

Fox, A. D., M. R. Anderson, G. Bartlett, J. Valverde, J. L. Starrels, and C. O. Cunningham. 2014. Health outcomes and retention in care following release from prison for patients of an urban post-incarceration transitions clinic. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 25(3):1139–1152.

Fox, A. D., A. Chamberlain, T. Frost, and C. O. Cunningham. 2015. Harm reduction agencies as a potential site for buprenorphine treatment. Substance Abuse 36(2):155–160.

GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office). 2016. Opioid addiction: Laws, regulations, and other factors can affect medication-assisted treatment access. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Accountability Office. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/680050.pdf (accessed February 12, 2019).

Gordon, M. S., F. J. Vocci, T. T. Fitzgerald, K. E. O’Grady, and C. P. O’Brien. 2017. Extended-release naltrexone for pre-release prisoners: A randomized trial of medical mobile treatment. Contemporary Clinical Trials 53:130–136.

Green, T. C., J. Clarke, L. Brinkley-Rubinstein, B. D. L. Marshall, N. Alexander-Scott, R. Boss, and J. D. Rich. 2018. Postincarceration fatal overdoses after implementing medications for addiction treatment in a statewide correctional system. JAMA Psychiatry 75(4):405–407.

Gunderson, E. W., X. Q. Wang, D. A. Fiellin, B. Bryan, and F. R. Levin. 2010. Unobserved versus observed office buprenorphine/naloxone induction: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Addictive Behaviors 35(5):537–540.

Hall, G., C. J. Neighbors, J. Iheoma, S. Dauber, M. Adams, R. Culleton, F. Muench, S. Borys, R. McDonald, and J. Morgenstern. 2014. Mobile opioid agonist treatment and public funding expands treatment for disenfranchised opioid-dependent individuals. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 46(4):511–515.

Harris, K. A., Jr., J. H. Arnsten, H. Joseph, J. Hecht, I. Marion, P. Juliana, and M. N. Gourevitch. 2006. A 5-year evaluation of a methadone medical maintenance program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 31(4):433–438.

Huhn, A. S., and K. E. Dunn. 2017. Why aren’t physicians prescribing more buprenorphine? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 78:1–7.

James, D. J., and L. E. Glaze. 2006. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Krawczyk, N., C. E. Picher, K. A. Feder, and B. Saloner. 2017. Only one in twenty justice-referred adults in specialty treatment for opioid use receive methadone or buprenorphine. Health Affairs 36(12):2046–2053.

Kuo, I., J. Brady, C. Butler, R. Schwartz, R. Brooner, D. Vlahov, and S. A. Strathdee. 2003. Feasibility of referring drug users from a needle exchange program into an addiction treatment program: Experience with a mobile treatment van and LAAM maintenance. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 24(1):67–74.

Lagisetty, P., K. Klasa, C. Bush, M. Heisler, V. Chopra, and A. Bohnert. 2017. Primary care models for treating opioid use disorders: What actually works? A systematic review. PLOS ONE 12(10):e0186315.

Langan, N. P., and B. M. Pelissier. 2001. Gender differences among prisoners in drug treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse 13(3):291–301.

Larochelle, M. R., D. Bernson, T. Land, T. J. Stopka, N. Wang, Z. Xuan, S. M. Bagley, J. M. Liebschutz, and A. Y. Walley. 2018. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: A cohort study. Annals of Internal Medicine 169(3):137–145.

Lee, J. D., E. Grossman, D. DiRocco, and M. N. Gourevitch. 2009. Home buprenorphine/naloxone induction in primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 24(2):226–232.

Lee, J. D., P. D. Friedmann, T. Y. Boney, R. A. Hoskinson, Jr., R. McDonald, M. Gordon, M. Fishman, D. T. Chen, R. J. Bonnie, T. W. Kinlock, E. V. Nunes, J. W. Cornish, and C. P. O’Brien. 2015. Extended-release naltrexone to prevent relapse among opioid dependent, criminal justice system involved adults: Rationale and design of a randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials 41:110–117.

Lee, J. D., P. D. Friedmann, T. W. Kinlock, E. V. Nunes, T. Y. Boney, R. A. Hoskinson, Jr., D. Wilson, R. McDonald, J. Rotrosen, M. N. Gourevitch, M. Gordon, M. Fishman, D. T. Chen, R. J. Bonnie, J. W. Cornish, S. M. Murphy, and C. P. O’Brien. 2016. Extended-release naltrexone to prevent opioid relapse in criminal justice offenders. New England Journal of Medicine 374(13):1232–1242.

Liebschutz, J. M., D. Crooks, D. Herman, B. Anderson, J. Tsui, L. Z. Meshesha, S. Dossabhoy, and M. Stein. 2014. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine 174(8):1369–1376.

Lincoln, T., B. D. Johnson, P. McCarthy, and E. Alexander. 2018. Extended-release naltrexone for opioid use disorder started during or following incarceration. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 85:97–100.

Matusow, H., S. L. Dickman, J. D. Rich, C. Fong, D. M. Dumont, C. Hardin, D. Marlowe, and A. Rosenblum. 2013. Medication assisted treatment in U.S. drug courts: Results from a nationwide survey of availability, barriers and attitudes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 44(5):473–480.

McElrath, K. 2018. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction in the United States: Critique and commentary. Substance Use & Misuse 53(2):334–343.

McKenzie, M., N. Zaller, S. L. Dickman, T. C. Green, A. Parihk, P. D. Friedmann, and J. D. Rich. 2012. A randomized trial of methadone initiation prior to release from incarceration. Substance Abuse 33(1):19–29.

Mojtabai, R., C. Mauro, M. M. Wall, C. L. Barry, and M. Olfson. 2019. Medication treatment for opioid use disorders in substance use treatment facilities. Health Affairs 38(1):14–23.

Moore, K. E., W. Roberts, H. H. Reid, K. M. Z. Smith, L. M. S. Oberleitner, and S. A. McKee. 2019. Effectiveness of medication assisted treatment for opioid use in prison and jail settings: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 99:32–43.

Naeger, S., R. Mutter, M. M. Ali, T. Mark, and L. Hughey. 2016. Post-discharge treatment engagement among patients with an opioid-use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 69:64–71.

NARR (National Alliance for Recovery Residences). 2018. MAT capable recovery residences: How state policy makers can enhance and expand capacity to adequately support medication assisted recovery. https://narronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/NARR_MAT_guide_for_state_agencies.pdf (accessed February 28, 2019).

Novick, D. M., E. F. Pascarelli, H. Joseph, E. A. Salstiz, B. L. Richman, D. C. Des Jarlais, M. Anderson, V. P. Dole, and M. E. Nyswander. 1988. Methadone maintenance patients in general medical practice: A preliminary report. JAMA 259(22):3299–3302.

Nunn, A., N. Zaller, S. Dickman, C. Trimbur, A. Nijhawan, and J. D. Rich. 2009. Methadone and buprenorphine prescribing and referral practices in U.S. prison systems: Results from a nationwide survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 105(1–2):83–88.

Patterson Silver Wolf, D. A. 2018. The new social work. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work 15(6):695–706.

Peters, R. H., P. E. Greenbaum, J. F. Edens, C. R. Carter, and M. M. Ortiz. 1998. Prevalence of DSM-IV substance abuse and dependence disorders among prison inmates. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 24(4):573–587.

Peterson, C., L. Xu, C. A. Mikosz, C. Florence, and K. A. Mack. 2018. U.S. hospital discharges documenting patient opioid use disorder without opioid overdose or treatment services, 2011–2015. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 92:35–39.

Ramsey, A. 2015. Integration of technology-based behavioral health interventions in substance abuse and addiction services. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 13(4):470–480.

Rich, J. D., M. McKenzie, D. C. Shield, F. A. Wolf, R. G. Key, M. Poshkus, and J. Clarke. 2005. Linkage with methadone treatment upon release from incarceration: A promising opportunity. Journal of Addictive Diseases 24(3):49–59.

Rich, J. D., M. McKenzie, S. Larney, J. B. Wong, L. Tran, J. Clarke, A. Noska, M. Reddy, and N. Zaller. 2015. Methadone continuation versus forced withdrawal on incarceration in a combined U.S. prison and jail: A randomised, open-label trial. Lancet 386(9991):350–359.

Rosenthal, R. N., and V. V. Goradia. 2017. Advances in the delivery of buprenorphine for opioid dependence. Drug Design, Development and Therapy 11:2493–2505.

Salsitz, E. A., H. Joseph, B. Frank, J. Perez, B. L. Richman, N. Salomon, M. F. Kalin, and D. M. Novick. 2000. Methadone medical maintenance (MMM): Treating chronic opioid dependence in private medical practice—A summary report (1983–1998). Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine 67(5–6):388–397.

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 2016. Reports of the Surgeon General. In Facing addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

SAMHSA. 2018a. Buprenorphine training for physicians. https://www.samhsa.gov/medicationassisted-treatment/training-resources/buprenorphine-physician-training (accessed January 15, 2019).

SAMHSA. 2018b. Qualify for nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) waiver. https://www.samhsa.gov/programs-campaigns/medication-assisted-treatment/training-materials-resources/qualify-np-pa-waivers (accessed January 15, 2019).

Scheuermeyer, F. X., E. Grafstein, J. Buxton, K. Ahamad, M. Lysyshyn, S. DeVlaming, G. Prinsloo, C. Van Veen, A. Kestler, and R. Gustafson. 2018. Safety of a modified community trailer to manage patients with presumed fentanyl overdose. Journal of Urban Health, October 15 [Epub ahead of print].

Schwartz, R. P., S. M. Kelly, K. E. O’Grady, D. Gandhi, and J. H. Jaffe. 2011. Interim methadone treatment compared to standard methadone treatment: 4-month findings. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 41(1):21–29.

Socias, M. E., E. Wood, T. Kerr, S. Nolan, K. Hayashi, E. Nosova, J. Montaner, and M. J. Milloy. 2018. Trends in engagement in the cascade of care for opioid use disorder, Vancouver, Canada, 2006–2016. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 189:90–95.

Torrens, M., F. Fonseca, C. Castillo, and A. Domingo-Salvany. 2013. Methadone maintenance treatment in Spain: The success of a harm reduction approach. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 91(2):136–141.

Trivedi, M. H., and E. J. Daly. 2007. Measurement-based care for refractory depression: A clinical decision support model for clinical research and practice. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 88(Suppl 2):S61–S71.

Trowbridge, P., Z. M. Weinstein, T. Kerensky, P. Roy, D. Regan, J. H. Samet, and A. Y. Walley. 2017. Addiction consultation services—Linking hospitalized patients to outpatient addiction treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 79:1–5.

Tuchman, E., and E. Drucker. 2001. MMT & beyond—Office-based methadone prescribing. http://www.methadone.org/downloads/documents/atf_2001_mmt_&_beyond.pdf (accessed February 12, 2019).

Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., P. Seth, R. M. Gladden, C. L. Mattson, G. T. Baldwin, A. Kite-Powell, and M. A. Coletta. 2018. Vital signs: Trends in emergency department visits for suspected opioid overdoses—United States, July 2016–September 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67(9):279–285.

Weintraub, E., A. D. Greenblatt, J. Chang, S. Himelhoch, and C. Welsh. 2018. Expanding access to buprenorphine treatment in rural areas with the use of telemedicine. American Journal of Addiction 27(8):612–617.

Weiss, R. D., and V. Rao. 2017. The prescription opioid addiction treatment study: What have we learned. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 173(Suppl 1):S48–S54.

Zur, J., J. Tolbert, J. Sharac, and A. Markus. 2018. The role of community health centers in addressing the opioid epidemic. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-role-of-community-health-centers-in-addressing-the-opioid-epidemic (accessed February 12, 2019).