1

Introduction

This introductory chapter provides an overview of traumatic brain injury (TBI), including how it is defined and its incidence and prevalence. The chapter then reviews the organization of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and offers a brief history of the VA’s compensation and pension (C&P) program. The chapter introduces the reader to the VA’s disability compensation and disability claims process, including the C&P exam. The chapter provides the study’s Statement of Task, as described in Congressional legislation (see Appendix A), which led to the VA’s request for the study. Finally, the chapter presents the committee’s approach to the task and the organization of the overall report. The committee relied on the VA’s Office of Inspector General’s Report No. 15-01580-108, published February 27, 2018, for background information.1

TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY

Traumatic brain injury is defined as an insult to the brain from an external force that leads to temporary or permanent impairment of cognitive, physical, or psychosocial function. TBI is a form of acquired brain injury, and it may be open (penetrating) or closed (non-penetrating) and can be categorized as mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the clinical presentation (Gennarelli and Graham, 2005). Numerous organizations have defined TBI, and a compilation of those definitions can be found in Appendix B; additionally, Chapter 2 provides detailed information about TBI.

TBI IN THE U.S. POPULATION

TBI is a serious public health problem in the United States, in both civilian and military populations. Each year traumatic brain injuries contribute to a substantial number of deaths and cases of permanent disability (CDC, 2017). While not all blows or jolts to the head result in a TBI, many do. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that in 2013, 2.8 million Americans were diagnosed with TBI. Among civilians, TBIs accounted for approximately 2.5 million emergency department (ED) visits, 282,000 hospitalizations, and

___________________

1 Healthcare Inspection Review of Montana Board of Psychologists Complaint and Assessment of VA Protocols for Traumatic Brain Injury Compensation and Pension Examinations (2018).

56,000 deaths in 2013. The majority of these civilian incidents were due to falls (47 percent) or being struck by or against an object (15 percent). From 2007 to 2013, motor vehicle–related TBIs have decreased, but TBIs due to falls in older adults have increased. In 2013, 2.2 percent of all civilian deaths in the United States were attributed to TBI (CDC, 2017).

CDC has been the source of the frequently cited estimates in the United States for the prevalence of disability in civilians due to TBI (Selassie et al., 2008; Thurman et al., 1999; Zaloshnja et al., 2008). The estimates are based on 1-year outcomes following acute hospitalization in single states, to which assumptions about mortality were applied. Using data from Colorado, Thurman and colleagues (1999) estimated that in 1996, 2.0 percent of the U.S. population experienced disability due to TBI. Extrapolating from data from South Carolina, Zaloshnja and colleagues (2008) estimated that 1.1 percent of the U.S. population, or 3.2 million people, had long-term disability associated with TBI. The primary difference in the two estimates is the application of more pessimistic mortality assumptions to the 2008 data. The authors identified multiple limitations, including that their estimates relied solely on hospitalized patients, thus excluding disability that might arise from injuries that did not result in hospitalization.

The prevalence of disability estimated from general population surveys would circumvent the limitation of using hospitalization data, but only one such survey has been conducted to date. Using the French National Disability and Health Survey, Jourdan and colleagues (2018) estimated the prevalence of disability due to TBI to be 0.7 percent, which is lower than follow-up data in single American states. The authors noted that their estimate is likely to be conservative, and suggested that the fact that their estimate is lower than CDC estimates (2003) might, in part, be due to the lower incidence of medically treated TBI in Europe. The French National Disability and Health Survey relied on respondents to identify their current disability arising from TBI. For impairments that are immediate and persistent following injury, such self-identification could be reliable. However, the disabling effects of an injury that emerged some time after the injury occurred could be attributed to other causes.

There is growing recognition that even mild TBIs in childhood might introduce a risk for disability in later life (CDC, 2003; Corrigan and Hammond, 2013; Masel and DeWitt, 2010). TBI is a well-established risk factor for dementia generally (Barnes et al., 2018; Fann et al., 2018) as well as for Parkinson’s disease (Gardner et al., 2018; IOM, 2009), and there is emerging evidence that a lifetime history of TBI might affect cognition and mobility in independently living older adults without dementia (Gardner et al., 2017; Peltz et al., 2017). Repeated blows to the head have been implicated in later, degenerative disease processes, specifically chronic traumatic encephalopathy (Aldag et al., 2017; Asken et al., 2017; Iacono et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2017; Vile and Atkinson, 2017; Wilson et al., 2017). Whiteneck and colleagues (2016) analyzed survey data on the co-occurrence of disability and TBI regardless of the need for hospitalization and concluded that the prevalence of disability due to TBI could easily be triple that based on hospitalizations only. Yi and colleagues (2017) found that adults with a history of TBI and loss of consciousness had an increased risk of current, self-reported disability.

A complete assessment of disability due to TBI would account for non-hospital-treated injuries as well as the later development of future consequences. CDC (2015) noted that national TBI-related disability is based on extrapolations of one-time state-level estimates of lifetime TBI-related disability (Selassie et al., 2008; Zaloshnja et al., 2008). CDC concluded there is a need to improve TBI surveillance of both incidence and prevalence by capturing TBIs treated in non-hospital settings or not receiving medical care, among other types of monitoring (CDC,

2015). Despite difficulties in obtaining the information, quantifying lifetime histories of TBI, including timing and severity, may be crucial to understanding the full public health burden.

TBI IN THE MILITARY

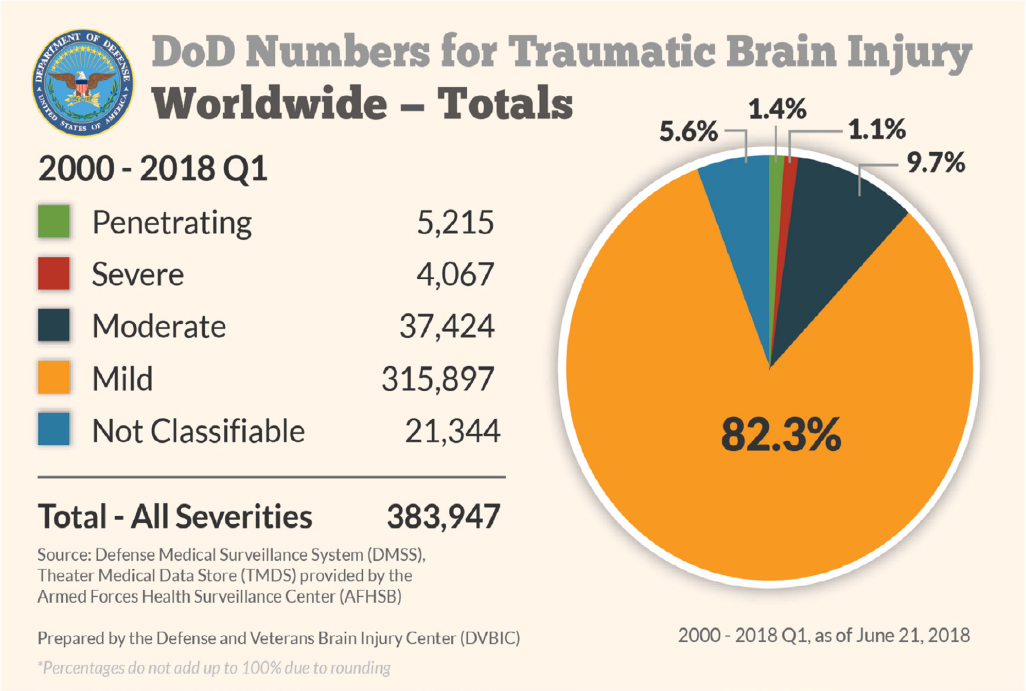

TBIs have been an increasing cause of casualty and disability in the military since the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan began, and TBI has become known as the signature injury for those veterans. A 2017 Department of Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) report estimates that 22 percent of all combat casualties from Iraq and Afghanistan are due to TBIs (VA, 2017). A 2019 DVBIC report estimates that more than 375,000 incidents of TBI were incurred in the military between the years of 2000 and 2018 (see Figure 1-1), primarily outside of combat, such as training accidents, motor vehicle collisions, and sport-related incidents (DVBIC, 2010). A minority of injuries are incurred in combat, with mechanisms including penetrating and blast-induced TBIs. The principal source of blast injuries is one or more encounters with a blast wave produced by a detonated improvised explosive device as well as large ammunitions and some firearms, while penetrating TBIs may be due to gunshot wounds as well as shrapnel associated with blasts. Consistent with rates observed in civilian populations, approximately 80 percent of TBIs in the military are mild in severity (see Figure 1-1).

SOURCE: DVBIC, 2019.

OVERVIEW OF THE ORGANIZATION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS

The VA is divided into the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA), and the National Cemetery Administration. VHA provides health services to qualified veterans and, related to the committee’s task, arranges medical exams for veterans who are filing for disability compensation. VBA focuses on disability and is distinct from VHA. It provides numerous types of services and benefits to service members, veterans, and their families. In particular, VBA oversees the delivery of disability compensation, which is a tax-free monetary benefit paid to veterans with disabilities that are the result of disease or injury incurred or aggravated during active military service (VA, 2018a).

Disability compensation is based on the severity of the service-connected medical condition and can range from 0 to 100 percent disability depending on the severity of the disabling condition (see Table 1-1). The VA regards disability as an intersection of service connection, diagnosis, and function. The VA awards disability compensation to people who sustain injuries from military service, regardless of their ability to work (VA Law, 2018).

The VA is the second largest federal department after the Department of Defense. The proposed fiscal year (FY) 2019 budget for the VA is $198.6 billion. The proposed budget represents an increase of $12.1 billion over 2018. The budget included $88.9 billion in discretionary funding for VA medical care, including medical collections,2 which is $6.8 billion (8.3 percent) above the FY 2018 budget. The budget also includes $109.7 billion in mandatory funding for benefit programs, $5.3 billion (5.1 percent) above FY 2018 (VA, 2018b). The 2019 request also will support 366,358 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees3 (see Table 1-2). The 2020 advance appropriations request includes $79.1 billion in discretionary funding for medical care, including collections (see footnote 2), and $121.3 billion in mandatory funding for veterans benefits programs (compensation and pensions, readjustment benefits, and veterans insurance and indemnities accounts).

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS COMPENSATION SYSTEM4

The beginnings of the U.S. disability compensation system can be traced back to 1636, when the Pilgrims of Plymouth Colony were at war with the Pequot Indians. The Pilgrims passed a law stating that disabled soldiers would be supported by the colony. Later, the Continental Congress of 1776 encouraged enlistments during the Revolutionary War by providing pensions to disabled soldiers. In 1811 the federal government authorized the first domiciliary and medical facility for veterans. Also in the 19th century, assistance programs for veterans were expanded to include benefits and pensions not only for veterans, but also for their widows and dependents.

___________________

2 Medical collections include the assessment of fees, referred to as co-payments, from certain veterans who receive inpatient or outpatient health care, medications, or extended care services. Such debts are subject to interest, late payment charges, and referral for collection purposes.

3 The 2019 VA budget request includes 324,701 FTEs for VHA and 23,692 FTEs for VBA.

4 The text in this section has been excerpted from VA History in Brief (VA, 2018e).

TABLE 1-1 Disability Compensation Rate Table for 2018 (in Dollars) per Month

| Disability Percent | 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% | 70% | 80% | 90% | 100% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veteran Alone | 136.24 | 269.30 | 417.15 | 600.90 | 855.41 | 1,083.52 | 1,365.48 | 1,587.25 | 1,783.68 | 2,973.86 |

| Veteran & Spouse | 466.15 | 666.90 | 937.41 | 1,182.52 | 1,481.48 | 1,719.25 | 1,932.68 | 3,139.67 | ||

| Veteran, Spouse, & 1 Child | 503.15 | 714.90 | 998.41 | 1,255.52 | 1,566.48 | 1,816.25 | 2,041.68 | 3,261.10 | ||

| Veteran & 1 Child | 450.15 | 644.90 | 910.41 | 1,149.52 | 1,442.48 | 1,675.25 | 1,882.68 | 3,084.75 | ||

| Additional Children | 24.00 | 32.00 | 41.00 | 49.00 | 57.00 | 65.00 | 74.00 | 82.38 | ||

| Additional Schoolchild | 79.00 | 106.00 | 133.00 | 159.00 | 186.00 | 212.00 | 239.00 | 266.13 | ||

| A&A for Spouse | 46.00 | 61.00 | 76.00 | 91.00 | 106.00 | 122.00 | 137.00 | 152.06 |

NOTES: A&A = aid and attendance, which provides increased monthly pension if a veteran requires the aid of another person to perform personal functions. If veteran has a spouse who requires A&A, add “A&A for spouse” to the amount of dependency and rate code above.

SOURCE: Veterans Aid Benefit, 2018.

TABLE 1-2 VA FTE Employees by Administration and Office

| 2017 Actual | 2018 Request | 2019 Request | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VHA | 313,512 | 318,944 | 324,701 |

| VBA | 22,408 | 22,812 | 23,692 |

| National Cemetery Administration | 1,847 | 1,923 | 1,941 |

| Office of Information Technology | 7,241 | 7,889 | 8,138 |

| General Administration | 2,524 | 2,937 | 3,035 |

| Board of Veterans’ Appeals | 840 | 1,105 | 1,025 |

| Office of the Inspector General | 745 | 855 | 827 |

| Supply Funds | 1,145 | 1,150 | 1,150 |

| Franchise Funds | 1,314 | 1,750 | 1,849 |

| Total VA | 351,576 | 359,365 | 366,358 |

SOURCE: VA, 2018c.

Following the Civil War, many state veterans’ homes were established, and indigent and disabled veterans of the Civil War, Indian Wars, Spanish-American War, and Mexican Border period, as well as discharged members of the Armed Forces, received care at those homes. In 1917 Congress established a new system of veterans’ benefits, including programs for disability compensation, insurance for service personnel and veterans, and vocational rehabilitation for the disabled.

In 1924 veterans’ benefits were liberalized to cover disabilities that were not service-related. In 1928 admission to the national homes was extended to women and National Guard and militia veterans. On July 21, 1930, President Herbert Hoover signed Executive Order 5398 and elevated the Veterans Bureau to a federal administration—creating the Veterans Administration. At that time the National Homes and Pension Bureau also joined the VA. The three component agencies became bureaus within the Veterans Administration. Brig. Gen. Frank T. Hines, who had directed the Veterans Bureau for 7 years, was named the first Administrator of Veterans Affairs. Following World War II there was a vast increase in the veteran population, and Congress endorsed large numbers of new benefits for war veterans, the most significant of which was the World War II GI Bill, signed into law on June 22, 1944.

In 1945 the VA Schedule for Rating Disabilities (VASRD) underwent its last major revision in an effort to address World War II veterans’ organ system injuries and illnesses. In a significant change, the revised VASRD allowed the VA to reevaluate a veteran and change the veterans’ disability rating. The revised 1945 version of the VASRD forms the foundation of the VA Schedule for Rating Disabilities that is in effect today. The VASRD will be discussed later in the chapter (and in more detail in Chapter 3).

The current VASRD assigns a percentage of disability, called a rating, based primarily on the severity of the veteran’s medical impairment or diagnosis. As noted above, the assigned percentages are in increments of 10 on a scale of 0 to 100. When the disability is judged service-connected and a compensable evaluation (at least 10 percent) is assigned, the veteran is entitled to receive monthly monetary benefits (see Table 1-1 for the range in monthly benefits).

More recently the VA amended its adjudication regulations to provide additional compensation benefits for veterans with residuals of traumatic brain injury.5 The final rule incorporates a benefit authorized by the Veterans’ Benefits Act of 2010. That act authorizes special monthly compensation for veterans with TBI who are in need of aid and attendance and, in the absence of such aid and attendance, require hospitalization, nursing home care, or other residential institutional care. (Note: This final rule related to special compensation for TBI was effective on June 7, 2018. The provisions of this final rule apply to all applications for benefits received by the VA on or after October 1, 2011, or that were pending before VA, the U.S. Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims, or the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit on October 1, 20116). See Appendix C for a timeline of the VA’s disability and veterans’ compensation policy.

Disability compensation often reflects the social, political, and economic values of the time. The legislators who create the policies on which disability compensation are based are often influenced by stakeholders, their constituents, and by the state of the relevant science and law at the time of their enactment.

DISABILITY COMPENSATION AND THE DISABILITY CLAIMS PROCESS

VBA provides different types of compensation to veterans, including disability compensation, health care, housing, and insurance benefits (VA, 2018d). Disability compensation is provided to service members or veterans with a service-connected injury. Disability compensation is

a tax free monetary benefit paid to veterans with disabilities that are the result of a disease or injury incurred or aggravated during active military service. Compensation might also be paid for post-service disabilities that are considered related or secondary to disabilities occurring in service and for disabilities presumed to be related to circumstances of military service, even though they might arise after service. (VA, 2018d)

To receive the VA disability, a veteran must submit a claim or have a claim submitted on his or her behalf. If a service member is separating from the military because of a medical condition, then the VA disability process begins automatically as part of the Integrated Disability Evaluation System. A disability percentage is assigned in a process that is detailed in Chapter 3 of this report and summarized in Box 1-1.

According to the VA, the factors affecting the length of time it takes to process a claim include the type of claim filed, the number and complexity of the claimed conditions (for example, comorbidities), and the availability of evidence to support the claim. If the veteran does not agree with the decision, there is an appeals process. The benefits and appeals procedures will be discussed in detail in Chapter 3.

The process for determining eligibility for disability benefits resulting from a TBI involves several steps, the first of which is a TBI diagnosis. If the TBI diagnosis had occurred

___________________

5 Residuals of TBI include three main areas of dysfunction that might result from sustaining a TBI. These might have profound effects on functioning, including cognitive, emotional/behavioral, and physical. “Residual” is a term used by the VA in its VASRD and DBQ (Disability Benefits Questionnaire), but the scientific community uses the term “sequela” to indicate outcomes resulting from a TBI.

6Federal Register, Vol. 83, No. 89 (Tuesday, May 8, 2018), Rules and Regulations 20735 FR.

during military service by Department of Defense personnel, then VBA’s policy is to accept that diagnosis. If, however, a veteran does not have a TBI diagnosis, then the VA requires that the diagnosis be made by a neurologist, neurosurgeon, physiatrist, or psychiatrist prior to the completion of the disability evaluation (see Chapter 2 for a further discussion about the expertise necessary for diagnosing TBI).

For veterans with a previous TBI diagnosis, the C&P examination is performed to evaluate the current state of any residuals resulting from the TBI. The exam can be made by any compensation-and-pension clinician certified through a program established by the Office of Disability and Medical Assessment, regardless of specialty.7 The examination might also be completed by one of the required specialists who performed the first part of the examination (i.e., provided the TBI diagnosis). VBA might send the veteran for a TBI disability examination to an outside contractor (generally to one of the four specialists required for a diagnosis), or VBA staff might send an examination request to VHA or have its contractors perform the exam; the VBA employee processes the application generally based on which path might be fastest.

___________________

7 The certification process includes completion of a TBI training module, which is a 1-hour course.

COMPENSATION AND PENSION EXAMINATION

After a claim is filed with VBA, if the VBA employee determines there needs to be additional medical evidence,8 a C&P exam is completed by a VHA clinician or VBA-contracted clinician to provide medical information to VBA to help determine the presence and degree of medical impairment incurred by the veteran. The C&P exam should note the diagnosis and the medical nature of the condition, and record all requested measurements and test results in a Disability Benefits Questionnaire (DBQ). It should be noted that, as the title suggests, the DBQs are questionnaires and therefore provide limited information that is relevant only to making the rating. The DBQs do not document all C&P examination findings. The DBQ provides medical information that is directly relevant to the VA schedule of rating disease, providing the majority of the medical evidence that VA rating specialists need as they start to process the claim. There are more than 70 DBQs for various medical conditions, including one that is specific to residuals of TBI (see Appendix D).

THE VA’S SCHEDULE FOR RATING DISABILITIES: THE VASRD

After VBA receives all information necessary to process the claim, a VBA rater assesses all the information necessary to rate the claim based on the criteria in the VASRD. The VASRD is the collection of federal regulations used by VBA raters to assign disability ratings. The VASRD is encoded in Title 38 Code of Federal Regulations Part 4 (see Appendix E). TBI residuals are evaluated in the VASRD under diagnostic code 8045. Disability ratings are based on an individual’s functioning in three areas: cognitive, emotional/behavioral, and physical.

The intent of the VASRD is to consistently rate every service-connected condition that has been diagnosed in a service member. Each disabling condition is evaluated based on the veteran’s symptoms and functional abilities. The criteria for symptoms and functional abilities in the TBI DBQ are aligned with those noted in the VASRD (further discussed in Chapter 3). Once all of the evidence is submitted and reviewed for a service-connected disability, VBA assigns a disability rating based on the VASRD criteria.

VA disability ratings can be adjusted over time because the VA retains the right to reexamine a disability rating as the veteran’s condition might improve. Additionally, if a veteran does not agree with the rating decision, he or she can submit an appeal to have the case reviewed (the appeals process is discussed further in Chapter 3).

STATEMENT OF TASK

Public Law 114-315 (see Appendix A), passed December 16, 2016, required the VA to contract with the National Academies to provide an independent review of the process by which the VA assesses impairment resulting from TBI for purposes of awarding disability compensation.9 In response to that mandate, the VA requested a comprehensive review of examinations conducted by the VA of individuals who submit claims to the Secretary of

___________________

8 VBA can use information in the veteran’s health record to adjudicate the claim, if the information is sufficiently complete for rating purposes.

9 Public Law 114-315, the Jeff Miller and Richard Blumenthal Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 2016. Section 110. December 16, 2016.

Veterans Affairs for compensation for traumatic brain injury. The committee will review the process by which impairments that result from TBI, for purposes of awarding disability compensation, are assessed. The specific Statement of Task is in Box 1-2.

APPROACH TO THE TASK

A committee of 15 experts who have expertise in emergency medicine, neurology, neurosurgery, psychiatry, psychology, physical medicine and rehabilitation, epidemiology, and statistics was assembled. The committee members held five meetings over the course of 1 year. The committee members met with representatives from VHA and VBA at its first three meetings, during open sessions, so that they could understand the issues and various department processes. The committee also met with VBA quality assurance staff, VHA clinicians, and raters to discuss the evaluation of TBI and to better understand the role of those filling out the § 4.124a—Schedule of ratings, 8045, that is, the residuals of traumatic brain injury (see Appendix E).

Inasmuch as the legislation, directing the committee’s study, called for an assessment of adequacy of the tools and protocols used by the VA to provide examinations, a determination of which credentials are necessary for health care specialists and providers to perform such examinations, and to make recommendations for legislative or administrative action for improving the adjudication of veterans’ claims, the committee found it necessary to review and comment on all aspects of the adjudication process (i.e., from diagnosis to final decision making regarding veterans’ claims).

Finally, although the VA provided a great deal of information to the committee regarding the details of the process that the committee was reviewing, the committee directed the staff to conduct broad literature searches for additional relevant information. Numerous published papers, government reports, and other documents were gathered and reviewed by the staff and the committee.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

The report is organized into five chapters. Chapter 1 provides introductory material intended to acquaint the reader with background information about the VA and processes related to the committee’s task. Chapter 2 discusses the diagnosis and assessment of TBI, the difficulties in diagnosing mild TBI, and distinguishing TBI from posttraumatic stress disorder or other comorbidities. The chapter also discusses the neuropathology of TBI and the possible recovery trajectories of TBI. Chapter 3 provides a detailed description of the disability determination process for residuals of TBI and assesses the adequacy of the tools and training provided in the process. Chapter 4 explores the characteristics of a high-quality process for determining disability resulting from TBI (such as validity, reliability, and consistency of process). Finally, conclusions and recommendations are discussed in Chapter 5.

REFERENCES

Aldag, M., R. C. Armstrong, F. Bandak, P. S. F. Bellgowan, T. Bentley, S. Biggerstaff, K. Caravelli, J. Cmarik, A. Crowder, T. J. DeGraba, T. A. Dittmer, R. G. Ellenbogen, C. Greene, R. K. Gupta, R. Hicks, S. Hoffman, R. C. Latta, 3rd, M. J. Leggieri, Jr., D. Marion, R. Mazzoli, M. McCrea, J. O’Donnell, M. Packer, J. B. Petro, T. E. Rasmussen, W. Sammons-Jackson, R. Shoge, V. Tepe, L. A. Tremaine, and J. Zheng. 2017. The biological basis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy following blast injury: A literature review. Journal of Neurotrauma 34(S1):S26–S43.

Asken, B. M., M. J. Sullan, S. T. DeKosky, M. S. Jaffee, and R. M. Bauer. 2017. Research gaps and controversies in chronic traumatic encephalopathy: A review. JAMA Neurology 74(10):1255–1262.

Barnes, D. E., A. L. Byers, R. C. Gardner, K. H. Seal, W. J. Boscardin, and K. Yaffe. 2018. Association of mild traumatic brain injury with and without loss of consciousness with dementia in US military veterans. JAMA Neurology 75(9):1055–1061.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2003. Report to Congress on mild traumatic brain injury in the United States: Steps to prevent a serious public health problem. https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/mtbireport-a.pdf (accessed August 24, 2018).

CDC. 2015. Report to Congress on traumatic brain injury in the United States: Epidemiology and rehabilitation. https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/tbi_report_to_congress_epi_and_rehaba.pdf (accessed May 11, 2018).

CDC. 2017. Traumatic brain injury & concussion. https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/index.html (accessed August 24, 2018).

Corrigan, J. D., and F. M. Hammond. 2013. Traumatic brain injury as a chronic health condition. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 94(6):1199–1201.

DVBIC (Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center). 2010. Military traumatic brain injury and blast. http://dvbic.dcoe.mil/research/military-traumatic-brain-injury-and-blast (accessed August 24, 2018).

DVBIC. 2019. DOD worldwide numbers for TBI. https://dvbic.dcoe.mil/dod-worldwide-numbers-tbi (accessed March 21, 2019).

Fann, J. R., A. R. Ribe, H. S. Pedersen, M. Fenger-Gron, J. Christensen, M. E. Benros, and M. Vestergaard. 2018. Long-term risk of dementia among people with traumatic brain injury in Denmark: A population-based observational cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 5(5):424–431.

Gardner, R. C., C. B. Peltz, K. Kenney, K. E. Covinsky, R. Diaz-Arrastia, and K. Yaffe. 2017. Remote traumatic brain injury is associated with motor dysfunction in older military veterans. Journals of Gerontology, A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 72(9):1233–1238.

Gardner, R. C., A. L. Byers, D. E. Barnes, Y. Li, J. Boscardin, and K. Yaffe. 2018. Mild TBI and risk of Parkinson disease: A chronic effects of neurotrauma consortium study. Neurology 90(20):e1771–e1779.

Gennarelli, T. A., and D. I. Graham. 2005. Neuropathology. In Textbook of traumatic brain injury, edited by J. M. Silver, T. W. McAllister and S. C. Yudofsky. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. Pp. 27–50.

Iacono, D., S. B. Shively, B. L. Edlow, and D. P. Perl. 2017. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: Known causes, unknown effects. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America 28(2):301–321.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2009. Gulf War and health: Volume 7: Long-term consequences of traumatic brain injury. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Johnson, V. E., W. Stewart, J. D. Arena, and D. H. Smith. 2017. Traumatic brain injury as a trigger of neurodegeneration. Advances in Neurobiology 15:383–400.

Jourdan, C., P. Azouvi, F. Genet, N. Selly, L. Josseran, and A. Schnitzler. 2018. Disability and health consequences of traumatic brain injury: National prevalence. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 97(5):323–331.

Masel, B. E., and D. S. DeWitt. 2010. Traumatic brain injury: A disease process, not an event. Journal of Neurotrauma 27(8):1529–1540.

Peltz, C. B., R. C. Gardner, K. Kenney, R. Diaz-Arrastia, J. H. Kramer, and K. Yaffe. 2017. Neurobehavioral characteristics of older veterans with remote traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 32(1):E8–E15.

Selassie, A. W., E. Zaloshnja, J. A. Langlois, T. Miller, P. Jones, and C. Steiner. 2008. Incidence of long-term disability following traumatic brain injury hospitalization, United States, 2003. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 23(2):123–131.

Thurman, D. J., C. Alverson, K. A. Dunn, J. Guerrero, and J. E. Sniezek. 1999. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: A public health perspective. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 14(6):602–615.

VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 2017. Traumatic brain injury and PTSD: Focus on veterans. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/co-occurring/traumatic-brain-injury-ptsd.asp (accessed August 24, 2018).

VA. 2018a. About VBA. https://www.benefits.va.gov/benefits/about.asp (accessed August 24, 2018).

VA. 2018b. FY 2019 budget submission. https://www.va.gov/budget/products.asp (accessed June 15, 2018).

VA. 2018c. Department of Veterans Affairs—Budget in brief 2019. https://www.va.gov/budget/docs/summary/fy2019VAbudgetInBrief.pdf (accessed June 15, 2018).

VA. 2018d. Compensation. https://www.benefits.va.gov/compensation (accessed August 24, 2018).

VA. 2018e. History—Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). https://www.va.gov/about_va/vahistory.asp (accessed August 24, 2018).

VA Law (Veterans Law Group). 2018. Frequently asked questions. https://www.veteranslaw.com/faq (accessed August 28, 2018).

Veterans Aid Benefit. 2018. VA 2018 Compensation, SMC, and DIC Rates. https://www.veteransaidbenefit.org/claim_support_disc/5%20Reference%20Material/1%20Rate%20Tables%20for%202018/VA%202018%20Compensation,%20SMC%20and%20DIC%20Rates.pdf (accessed August 28, 2018).

Vile, A. R., and L. Atkinson. 2017. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: The cellular sequela to repetitive brain injury. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 41:24–29.

Whiteneck, G. G., J. P. Cuthbert, J. D. Corrigan, and J. A. Bogner. 2016. Prevalence of self-reported lifetime history of traumatic brain injury and associated disability: A statewide population-based survey. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 31(1):E55–E62.

Wilson, L., W. Stewart, K. Dams-O’Connor, R. Diaz-Arrastia, L. Horton, D. K. Menon, and S. Polinder. 2017. The chronic and evolving neurological consequences of traumatic brain injury. The Lancet Neurology 16(10):813–825.

Yi, H., J. D. Corrigan, B. Singichetti, J. A. Bogner, K. Manchester, J. Guo, and J. Yang. 2017. Lifetime history of traumatic brain injury and current disability among Ohio adults. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 33(4):E24–E32.

Zaloshnja, E., T. Miller, J. A. Langlois, and A. W. Selassie. 2008. Prevalence of long-term disability from traumatic brain injury in the civilian population of the United States, 2005. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 23(6):394–400.

This page intentionally left blank.