During the second panel of the workshop, three presenters talked about major initiatives in health care systems that have had major effects on suicide rates. These initiatives point toward the possibility of making much more extensive changes in health care systems, both in the United States and abroad, that could achieve for suicide prevention the successes achieved through prevention initiatives targeting health issues such as smoking or heart disease.

THE ORIGIN OF THE ZERO SUICIDE MODEL

In 2001 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released the report Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (IOM, 2001). As C. Edward Coffey, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and of neurology in the Baylor College of Medicine, recounted, the report observed that health care providers are well trained, are working as hard as they can, and are trying to do the right thing. But, as the report stated,

In its current form, habits, and environment, the health care system is incapable of giving Americans the health care they want and deserve. . . . The current care systems cannot do the job. Trying harder will not work. Changing systems of care will.

The report laid out six dimensions of ideal care. Such care is:

- Safe,

- Effective,

- Patient-centered,

- Timely,

- Efficient, and

- Equitable.

The report also provided 10 rules for designing a system that would achieve ideal care:

- Care equals relationships.

- Care is customized.

- Care is patient-centered.

- Share knowledge.

- Manage by fact.

- Make safety a system priority.

- Embrace transparency.

- Anticipate patient needs.

- Continually reduce waste.

- Professionals cooperate.

After the report was published, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) partnered with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) to launch the RWJF Pursuing Perfection Program, which had as its goal to demonstrate that ideal health care is attainable. Using the IOM report as a guide, the foundation sought applications for transformative plans to create health care systems that would approach ideal care within a timeframe of 2 years. From about 300 applications submitted in 2001, 12 finalists were selected, including the Perfect Depression Care Initiative proposed by the Behavioral Health Services Division of Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, Michigan. “We celebrated for about 10 seconds,” said E. Coffey, who was then chief executive officer of behavioral health services for the system and the principal investigator on the Perfect Depression Care Initiative. “Then we started thinking, what in the world are we going to do to try to transform our mental health care system?”

The finalists were required to develop “perfection” goals for each of the six dimensions of ideal care. The Henry Ford Perfect Depression Care Initiative accordingly established the following goals (Coffey, 2006, 2007):

- Safe care: Eliminate inpatient falls and medication errors.

- Effective care: Eliminate suicides.

- Patient-centered care: 100 percent of patients will be completely satisfied with their care.

- Timely care: 100 percent complete satisfaction.

- Efficient care: 100 percent complete satisfaction.

- Equitable care: 100 percent complete satisfaction.

The goal for effective care was initially unclear until a staff member, in one of the many meetings held to discuss the goals, said, “Well, perhaps if we were doing perfect depression care, nobody would die from suicide. Nobody would kill themselves.” Recounted E. Coffey: “At that moment, after we all got our breath back, our department was transformed. . . . That moment, essentially, was the birth of Zero Suicide.”

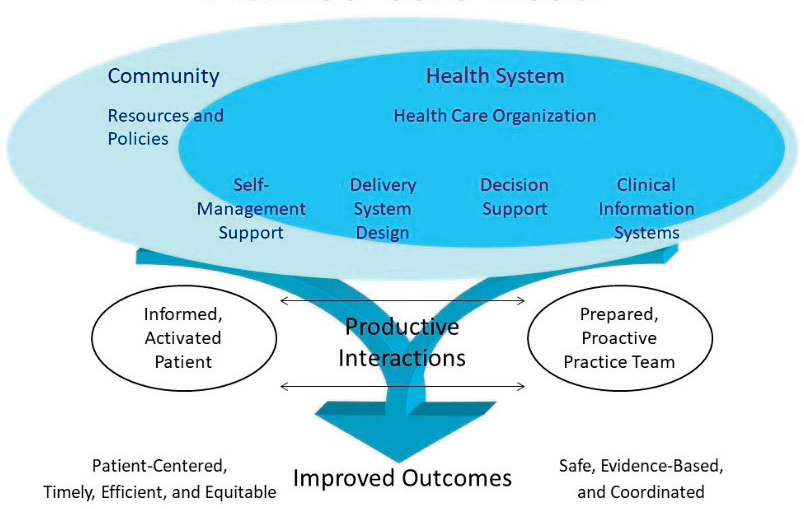

With zero suicides becoming the overarching goal, E. Coffey’s group adapted a planned care model designed to create productive interactions (see Figure 3-1). These interactions result from an informed and activated patient working closely with a prepared and proactive practice team. The elements of these interactions correspond closely with the goals of the IOM report.

During the first decade of the 21st century, the suicide rate was increasing in Michigan. However, after implementation of the Perfect Depression Care Initiative, the suicide rate for patients receiving mental health care in the Henry Ford Health System dropped by more than 75 percent, though the rate rose again in 2010 when the recession that began in 2008 was especially severe in Michigan (Coffey et al., 2015). In most years, the suicide rate for the system was close to that of the general population in Michigan, even though the expected suicide rate for people with an active mood disorder is approximately 21 times the rate for the general population, E. Coffey observed.

SOURCE: Presented by C. Edward Coffey on September 11, 2018, at the Workshop on Improving Care to Prevent Suicide Among People with Serious Mental Illness.

E. Coffey emphasized that depression is not the only risk factor for suicide. All the major mental disorders raise the risk of suicide, especially if they are comorbid with substance use disorder. “If you’re trying to bend the curve on suicide risk, you don’t want to focus just on depression.” They therefore worked to ensure that all their patients received “perfect” care.

Improvement projects are not complete until their results have been described and disseminated, noted E. Coffey. To address this need, the Perfect Depression Care team produced a series of articles describing the initiative and its results over time (Coffey, 2006, 2007; Hampton, 2010; Ahmedani et al., 2013; Coffey et al., 2013; Coffey and Coffey, 2016). The public feedback was very positive, including recognition as a best-in-class innovation by the Malcolm Baldrige examiners when they awarded the Henry Ford Health System the 2011 Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award. In 2012 the Perfect Depression Care Initiative was invited by Mike Hogan and David Covington to partner with the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, a partnership which has yielded a “hugely productive” collaboration that has embraced the goal of Zero Suicide (see the following section of this chapter). Other organizations, including the National Institute of Mental Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), have subsequently embraced the goals of the Zero Suicide model. International Zero Suicide summits beginning in 2014 have provided a way to exchange information and spread the program to other health care systems (see “International Actions on Suicide Prevention” later in this chapter). Early adopters of the Zero Suicide model have included an organization in Tennessee known as Centerstone, as well as the National Health Service, the Mersey Care Trust, and Zero Suicide Alliance, all in the United Kingdom.

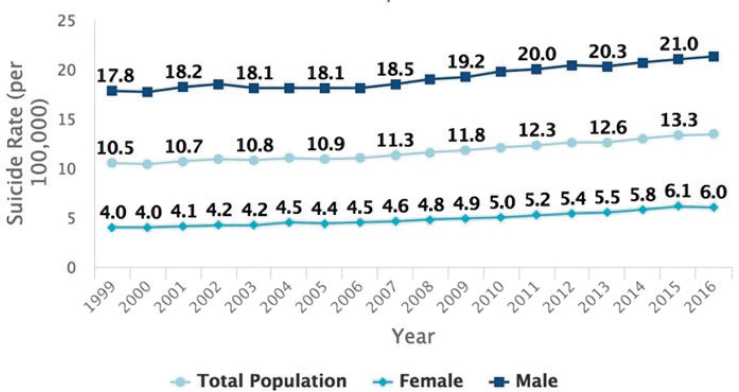

Such initiatives are desperately needed, said E. Coffey. As pointed out earlier in the workshop by Wilcox and Moutier, suicide rates have increased 30 percent over the past 15 years, with an even greater increase in some states (see Figure 3-2). “Despite all the great work that is being done, and all the great progress scientifically, and even despite Zero Suicide, the curve is moving in the wrong direction in this country.” A possible explanation for this discrepancy may lie in the distinction between zero suicide as an aspirational goal versus Zero Suicide as a firm goal that serves as an innovative driving force for transformation to ideal health care (Coffey, 2003). As an innovation, the Zero Suicide model has three key elements. The first is a radical new conviction that ideal health care is attainable. The second is a road map to achieve that vision (“pursuing perfection within a just culture”). The third is expertise in systems engineering to implement the vision.

The challenge today, said E. Coffey, is that Zero Suicide may be seen as a stand-alone aspirational goal rather than as an essential component in this tripartite model of transformation. “I don’t want to complain about

SOURCES: Presented by C. Edward Coffey on September 11, 2018, at the Workshop on Improving Care to Prevent Suicide Among People with Serious Mental Illness. From CDC, 2018.

any goal” that seeks to lower the suicide rate, he said, and a goal to reduce suicides by 20 percent before 2025 is great and should be encouraged. “But it may be that as long as we view Zero Suicide as an aspiration, we are backing away from being ‘all in,’ from being convinced that ideal health care is possible.” Experience with Perfect Depression Care suggests that audacious goals such as “Zero Suicide” are essential components in driving transformation, said E. Coffey, and that transformation rather than incremental improvement is what is needed to bend the curve on suicide and give patients the care they want and deserve.

DISSEMINATION AND EVIDENCE FOR ZERO SUICIDE

Even as the suicide rate has increased in the past 15 years, the age-adjusted death rates for heart disease, cancer, and stroke have fallen. Why has prevention for other causes of death been successful while suicide prevention has not been successful, asked Mike Hogan of Hogan Health Solutions.

With deaths from cardiovascular disease (CVD), the reduction in smoking accounts for 20 to 25 percent of the improvement. However, targeted preventive interventions with people who have well-established CVD risks had an even greater effect. The Zero Suicide movement seeks to establish suicide prevention as a goal and a priority in health care. The model, like

the successful efforts to reduce CVD deaths, emphasizes effective preventive interventions for those with elevated risk. But the health care system has not yet taken that goal to heart, Hogan said. Even in hospitals, a recent analysis found that the estimated number of inpatient deaths by suicide that occur each year ranges from 49 to 65 (Williams et al., 2018).

The Zero Suicide movement is also a care innovation, Hogan observed. It combines a quality improvement with a bundling of care, as has been the case with innovations applied to other health conditions. This point is made in the report Suicide Care in Systems Framework (Clinical Care and Intervention Task Force and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2011), which looked at the applicability of the Henry Ford initiative in the larger health care system.

Research has shown that suicidal behavior is distinct from mental disorders (Van Orden et al., 2010). Many people have suicidal thoughts, but relatively few progress to attempts (Millner et al., 2017; Klonsky et al., 2018). “For the average person [in the Millner et al. study], it was 2 years between ideation and attempt,” observed Hogan. “That’s a lot of time to intervene, but only if we know. And since we tend to not ask, we don’t know.” However, once people have reached a tipping point, the time to an attempt was short—from a few minutes to a few weeks. Developing the “capability” to kill oneself is the dangerous step, said Hogan—both the internal capability and the physical capability to act. In addition, no single pathway from ideation to suicide exists. “Life is complicated, genetics are complicated, genetic–environmental interactions are complicated.”

Health care settings provide places to intervene. First, more than 80 percent of people dying by suicide and more than 90 percent with attempts had health care visits in the previous 12 months. Of people who died from suicide, 45 percent had a primary care visit in the month before death, 19 percent had contact with mental health services in the month before, and 10 percent had an emergency department visit in the previous 60 days. The rates are even higher for older men, with 70 percent seeing a general practitioner within 30 days of a death by suicide. The risk of suicide death following inpatient psychiatric discharge is 44 times the population rate, observed Hogan. In short, the health care system has ample time to intervene. The question is whether it does.

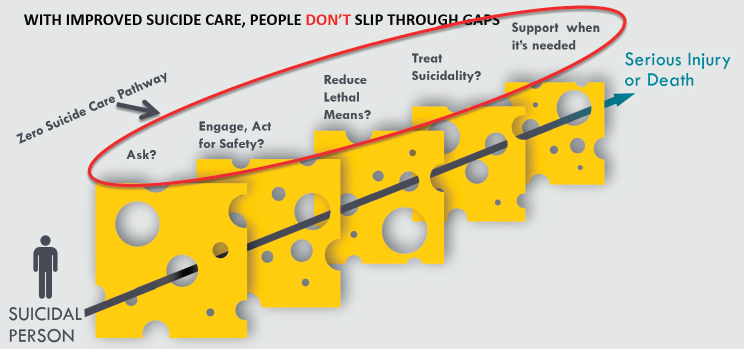

The second reason why suicide prevention in health care settings makes sense, said Hogan, is that evidence exists for effective—often brief—interventions that can be deployed feasibly in health care organizations. Hogan presented a mental model that is used by Zero Suicide to illustrate how people who die by suicide fall through successive gaps in the health care system (see Figure 3-3). The first gap, said Hogan, is whether people are asked about suicide. The second is whether health care providers engage and provide a safety planning intervention to give people the skill set and

SOURCES: Presented by Mike Hogan on September 11, 2018, at the Workshop on Improving Care to Prevent Suicide Among People with Serious Mental Illness. From Zero Suicide Institute, Education Development Center, 2018.

tools they need. Successive steps involve reducing lethal means, treating suicidality, and ensuring that interpersonal, structured support is available when needed. “These actions need to be done in a routine way within a health care setting,” said Hogan. “It’s a care pathway. Not doing this would be the equivalent of having people in care for diabetes and never getting an A1C level.”

Simon et al. (2013) examined the subsequent history of more than 75,000 people who completed the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 to screen for depression. Of those who subsequently died by suicide, 60 percent indicated elevated thoughts on question 9, which asks about “thoughts that you would be better off dead or hurting yourself in some way.” The suicide field has had a debate about whether it is possible to predict who is going to die, and “we shouldn’t be interested in predicting who’s going to die,” observed Hogan. “We should want to know who needs help. Cardiologists are not worried about [whether they can] predict when people are going to die of a heart attack and who that’s going to be. They identify risk factors and then they take action.” Based on the Simon et al. (2013) study, prediction of who needs suicide prevention are much better then high cholesterol scores are to predict a heart attack, Hogan said. “This is good enough evidence to act.”

Safety planning makes sense, is feasible, and has become widely used, but until recently it had not been well tested, said Hogan. However, Stanley et al. (2018) recently did an emergency department matched cohort comparison study with 1,640 patients with a suicide-related visit and 1,186 in

the intervention group. They tested a brief safety planning intervention plus telephone follow-up and found that the patients receiving the intervention had 45 percent fewer suicidal behaviors and were twice as likely to participate in follow-up care.

Means restriction is a critical part of a safety plan, and evidence and experience at a population level indicates that it works, said Hogan. In communities with a dominant means of suicide, restricting that means reduced suicide rates by about 40 percent. In addition, caring contacts, including phone calls, letters, texts, postcards, and visits, are effective. Denchev et al. (2018) found that caring letters work better than usual care and cost less, phone calls work even better, and cognitive behavioral therapy is also effective.

Evidence for the effectiveness of suicide-focused therapies over usual care comes from dialectical behavior therapy, cognitive therapy for suicide prevention, collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicide (CAMS), post-attempt counseling (from Denmark), and the Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program (from Switzerland). This evidence from randomized controlled trials demonstrates that such therapies are as effective as acute care interventions for cardiovascular disease, said Hogan. The idea of directly treating suicidality is “fundamentally relevant” to the workshop, he observed. “If somebody is suicidal and has a major mental illness, it’s no longer acceptable to just treat the major mental illness and hope that the suicidality resolves.”

The critical issue, said Hogan, is that the usual care for people at risk of suicide is unacceptably bad—“people are dying.” Importantly, this is not because of clinician error but because health care programs and systems have not put proven methods in place, leaving clinicians to manage care on their own. The Henry Ford Health System, Centerstone, and the Institute for Family Health have demonstrated reductions from baseline suicide rates of 60 to 80 percent. Hogan also made the point that Zero Suicide is a package made up of elements, each of which is known to be effective. “It makes sense that the overall package would work, because the elements work if they’re done with fidelity.” The Zero Suicide model includes an organizational assessment that is also a fidelity tool, Hogan said. A New York study of about 200 clinics found that clinics with higher fidelity scores had fewer suicides. This makes sense, he said, but we need more data to shift the late adopters.

The website zerosuicide.com lays out the basic tools needed to advance. In addition, leadership and elbow grease are critical, Hogan said. “The really big problem is getting health care to say it’s our responsibility to keep our patients alive” from this form of preventable death. Behavioral health settings are “starting to get up the adoption curve,” but primary care, emergency departments, and health care systems are “just at the beginning.”

Suicide risk is linked to but is distinct from other mental disorders, Hogan concluded. Interventions aimed at depression or bipolar disorder are important but not sufficient. Well-established interventions for suicide care now exist, and integrated treatment that attends to both mental illness and suicidality is likely to be more effective. Successful programs like Zero Suicide provide a care pathway and a protocol for treating and managing suicide risk that are embedded within clinics. These interventions need to be integrated “into the work of every mental health practitioner” and into health systems and settings, Hogan stated.

INTERNATIONAL ACTIONS ON SUICIDE PREVENTION

How does a movement spread, how does it produce action, how does it inspire people, asked David Covington, chief executive officer and president of Recovery Innovations, Inc. One way is through international declarations.

In 1989 a small group of people with diabetes, policy makers, and physicians gathered in a rural Italian village and conceived of an audacious proposal: that diabetes management should consist of co-management between an individual and a physician. “This vision has largely been realized,” said Covington. Many people no longer remember “when you had to go to a physician to get a blood level.” Today people with diabetes are, as expressed in that 1989 statement, co-responsible for their treatment.

In 2002, a small group gathered in the United Kingdom and decided to follow the model of the diabetes pioneers. They proclaimed that an individual having a first episode of psychosis would quickly move from diagnosis to treatment to recovery and live an ordinary life. Though the United States is still making progress on early intervention programs, the time to treatment after a first episode of psychosis in the United Kingdom has been slashed to a target of 22 days, “in large part because of an audacious vision and a pathway for beginning to make that happen.”

The 2011 report Suicide Care in Systems Framework (Clinical Care and Intervention Task Force and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2011) could have gathered dust on a shelf, said Covington. But people involved in the production of the report were inspired by the declarations emerging from international summits. In 2015, representatives of 13 countries produced the document “Zero Suicide: International Declaration for Better Healthcare,” which has been viewed many thousands of times throughout the world.1 At the same time, a series of global zero suicide summits began in 2014 in England, and the summits have grown in size

___________________

1 The declaration is available at http://riinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/zerosuicidedeclaration_2015draft.pdf (accessed November 27, 2018).

and scope ever since. Subsequent summits have been held in Atlanta (2015), Sydney (2017), and Rotterdam (2018), and the next summit is scheduled for the United Kingdom in 2020.

About the time of the first summit, peer leader Eduardo Vega said at a meeting Covington attended: “I don’t know that I am so much against suicide. But here is what I am definitely against: people dying alone and in despair.” This statement has become a platform for work going on around the world. In addition to the website zerosuicide.com mentioned by Hogan, the website zerosuicide.org is simultaneously creating a hub for innovation, Covington observed. It brings together not just the people normally involved in suicide prevention but educators, designers, and innovators who can help create an international dialogue and move the process forward.

Today, 90 organizations are part of the Zero Suicide Alliance in the United Kingdom, forming a confederation of providers who can exchange information and guidance. A current challenge is to take the movement into middle- and low-income countries and especially into Africa and South America.

FUNDING ISSUES

In response to a question about securing adequate funding for such initiatives, Hogan pointed out that the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA’s) suicide prevention grants now provide more funding than has been the case previously. Also, a small but important part of the 21st Century Cures Act was an adult suicide prevention program authorized for funding of $10 million per year. “This is a starting point,” said Hogan.

In addition, much of the progress to be made depends on redesigning the care that now exists, he explained. The suicide prevention activities that need to be done are not complicated, he added, but they have previously been out of scope and health care professionals, including behavioral health professionals, have not received training on them.

Finally, ways need to be found to get reimbursement for these activities, Hogan said. Currently, providers need to figure out setting by setting how to bill for suicide prevention activities. How do they bill for the development of a safety plan? How do they bill for follow-up?

Covington discussed the initial fear among some of the leaders of health care organizations that more screening and assessment would identify more individuals at risk, which would lead to a reduction of profitability. However, he and others had a hypothesis that the opposite would occur: that when health care professionals do not feel confident in their skills they unnecessarily push people in directions that result in increased and avoidable psychiatric inpatient hospitalization. The zero suicide approach can

produce a significant reduction in more intensive services for those most in need, he said. Furthermore, the savings may be ever greater at a system level.

Coffey responded by saying that more funding to address this problem cannot be expected. Therefore, “we’re going to have to fix it ourselves, we’re going to have to find the dividend in the work that we’re doing currently.” Stopping things that do not work will provide savings that can be invested in things that do work. He also mentioned the “heretical” idea that more screening is not necessarily the answer. “Screening has a place,” he said, but providers can spend “way too much time worrying about screening and the precise [risk] number. . . . Instead cut back on that and devote the resources to safety planning and getting much better at means restriction.”

RESISTANCE TO THE IDEA OF A ZERO SUICIDE GOAL

Nadine Kaslow, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Emory University School of Medicine, asked about the unanticipated consequences of zero suicide initiatives. Could they be a setup for failure and lead critics to question the overall initiative? On a related note, does the identification of people at risk of suicide in hospitals, with the constraints it puts on their autonomy and their identification as high risk, lead to humiliation and stigmatization, she asked.

Hogan responded that “I’m getting pretty old, I don’t have that much time, which leads me to say I don’t have time for [resistance]. I’m only interested in who wants to do something and what do you want to do now.” The other panelists had similar responses. Covington drew a distinction between half measures and full measures. For 70 years the Golden Gate Bridge did some things that saved lives, but it remained a very unsafe place. Finally, after many deaths and considerable pressure, the operators of the bridge decided to install nets extending from the sides of the bridge to stop people from using it for suicide. “They decided in their backyard they were going to take full ownership and do everything they could do. That’s what we’re really talking about for health care for which we’re responsible.”

E. Coffey responded that the zero suicide movement needs skeptics and that it is okay to be skeptical about zero suicide from a scientific perspective. But dealing with these criticisms takes time, and “as leaders we have to make a distinction between whether what we’re hearing is healthy skepticism versus cynicism.” This cynicism is not conducive to building a culture where people are asked to swing for a home run every time they come up to bat. “We have to build a safe environment where people are encouraged to innovate and be bold and audacious, but also at the same time to learn from mistakes.”

On the issue of stigmatization, Hogan lamented the sterile environments in hospitals that can result from suicide prevention efforts, such as eliminating ligatures that might be used in suicide attempts. But “morally, we can’t not eliminate that.” Health care systems also need to replace the things missing because of suicide prevention with other things that will be supportive and relationship centered, he said. Covington pointed out that the company for which he is chief executive officer runs 50 crisis programs and wellness programs in about 5 states, and these programs look different as a result of people with lived experiences being a substantial part of the staff. The people who are in the programs are referred to as guests rather than patients. “It’s more like a retreat than it is an institution, more like a home.”

Many people, including health care providers, have a fear of suicide and try to distance themselves from patients who are at risk, Hogan said. The presence of this fear suggests two fundamental tasks, he added. One is to create a culture that seeks perfection but does not cast blame. “That’s hard leadership work, but it’s foundational.” The second thing is to include people with lived experience in the planning, design, oversight, and conduct of this work:

We all felt that we were changing and learning something as we listened to Taryn. She’s not the only person who is a genius about this. A lot of people who have been through this experience have that to contribute.

ACTING ON THE EVIDENCE

Richard McKeon of SAMHSA said that a central part of the Zero Suicide initiative has been its recognition of the accumulating evidence that focusing only on an underlying mental health condition is insufficient to prevent suicide among those with such conditions. Suicide prevention needs to be a specific focus, he maintained. At the same time, behavioral health treatment within the health care system takes place in many contexts other than zero suicide programs, and these other contexts may have implications for preventing suicide among those with serious mental illness. “Should we be looking for ways to insert suicide prevention into those initiatives that are going to continue with or without suicide prevention?” he asked. “Is there a way that standard care for depression in primary care could be made more suicide mindful, or early intervention for psychosis?”

E. Coffey responded that one way to embed such care across the health care system is to focus on the safety plan:

I don’t think safety planning should be limited to people who are patients in the mental health care system. I would argue that every patient needs

a safety plan. Aren’t those with cancer at risk for suicide? I would start there. If you were to do one thing today that would make a difference in suicide care, I’d take becoming very serious about safety planning for every patient in our health care system.

Hogan responded with an anecdote about a Zero Suicide training boot camp, which they call Zero Suicide academies. One of the people attending the training was an internist in a small practice who seemingly would not need to know this level of detail about suicide prevention. When Hogan asked him at the end of the day what he thought, the internist responded, “Well, I don’t deal with this every day, but here’s what I’m thinking. The risk of this looks a lot like the risk for my patients of prostate cancer. There’s not a lot of that, but where there is, it’s pretty important.” He said that he was planning to add the suicide question to his Patient Health Questionnaire. Most of the time the responses will be negative. “But if there’s a concern, my staff will bring it to my attention, and I’ll make that the main focus of what I do with that patient in that visit.” Hogan thought that this was a brilliant response. “This is the big lift in primary care.”

With regard to specialty care, Hogan responded that the evidence demonstrates that anyone with a diagnosed mental disorder or receiving a behavioral treatment should be asked about suicide. If this generates a concern, actions need to be taken. “That’s a big change in primary care in emergency department settings, but we think that’s what the evidence today suggests.”

Finally, the moderator of the panel, Justin Coffey, vice president and chief information officer at the Menninger Clinic, commented on the safety provisions that have been installed at the Golden Gate Bridge. The netting installed beneath the bridge is not just about aesthetics.

It’s about what the net says, and what the net says is that we have a serious problem in this country. People don’t want to have to be reminded of that when they look at the netting, but it’s a reminder that we have a serious cultural problem, and it’s on one of our most significant engineering achievements. It’s such a contrast that people can’t accept it, and that’s at the heart of their problem.

The Zero Suicide effort has a similar issue. E. Coffey said:

Part of my worry personally about zero suicide is that when you talk about diabetes and about heart disease, those are natural consequences of health conditions and aging. They can be seen and framed within the natural process. When we start to talk about suicide and mental health, people don’t see it the same way. It’s about culture and the impact of our culture, and I’m concerned about our willingness to accept those things.

REFERENCES

Ahmedani, B. K., M. J. Coffey, and C. E. Coffey. 2013. Collecting mortality data to drive real-time improvement in suicide prevention. American Journal of Managed Care 19(11):e386-e390.

Clinical Care and Intervention Task Force and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2011. Suicide care in systems framework. Washington, DC: National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention.

Coffey, C. E. 2003. Pursuing perfect care in neuropsychiatry: Implications of the Institute of Medicine’s “Quality Chasm” report for neuropsychiatry. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 15:403-406.

Coffey, C. E. 2006. Pursuing perfect depression care. Psychiatric Services 57:1524-1526.

Coffey, C. E. 2007. Building a system of perfect depression care in behavioral health. Joint Commission Journal of Quality and Patient Safety 33:193-199.

Coffey, M. J., and C. E. Coffey. 2016. How we dramatically reduced suicide. NEJM Catalyst.https://catalyst.nejm.org/dramatically-reduced-suicide (accessed December 6, 2018).

Coffey, C. E., M. J. Coffey, and B. K. Ahmedani. 2013. An update on perfect depression care. Psychiatric Services 64(4):396.

Coffey, M. J., C. E. Coffey, and B. K. Ahmedani. 2015. Suicide in a health maintenance organization population. JAMA Psychiatry 72:294-296.

Denchev, P., J. L. Pearson, M. H. Allen, C. A. Claassen, G. W. Currier, D. F. Zatzick, and M. Schoenbaum. 2018. Modeling the cost-effectiveness of interventions to reduce suicide risk among hospital emergency department patients. Psychiatric Services 69(1):23-31.

Hampton, T. 2010. Depression care effort brings dramatic drop in large HMO population’s suicide rate. JAMA 303(19):1903-1905.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Klonsky, E. D., B. Y. Saffer, and C. J. Bryan. 2018. Ideation-to-action theories of suicide: A conceptual and empirical update. Current Opinion in Psychology 22:38-43.

Millner, A. J., M. D. Lee, and M. K. Nock. 2017. Describing and measuring the pathway to suicide attempts: A preliminary study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 47(3):353-369.

Simon, G. E., C. M. Rutter, D. Peterson, M. Oliver, U. Whiteside, B. Operskalski, and E. J. Ludman. 2013. Does response on the PHQ-9 Depression Questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death? Psychiatric Services 64(12):1195-1202.

Stanley, B., G. K. Brown, L. A. Brenner, H. C. Galfalvy, G. W. Currier, K. L. Knox, S. R. Chaudhury, A. L. Bush, and K. L. Green. 2018. Comparison of the safety planning intervention with follow-up vs usual care of suicidal patients treated in the emergency department. JAMA Psychiatry 75(9):894-900.

Van Orden, K. A., T. K. Witte, K. C. Cukrowicz, S. R. Braithwaite, E. A. Selby, and T. E. Joiner. 2010. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review 117(2):575-600.

Williams, S. C., S. P. Schmaltz, G. M. Castro, and D. W. Baker. 2018. Incidence and method of suicide in hospitals in the United States. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 44(11):643-650.

This page intentionally left blank.