The third and fourth panels of the workshop looked at two specific populations at high risk for suicide: military service members and veterans (summarized in this chapter) and Native Americans and American Indians (summarized in Chapter 5). Examining the issues surrounding these populations reveals both how different populations have different challenges and how some interventions can be effective across all populations.

PREVALENCE AND INTERVENTIONS

Suicide rates have been going up for veterans as well as for the general population, said Mike Colston, captain in the U.S. Navy Medical Corps and director of Mental Health Programs in the Health Services and Policy Oversight Office of the Department of Defense (DoD). As noted in Chapter 2, among states reporting in the National Violent Death Reporting System, every state, except for Nevada, had an increase in suicide rates between 1999 and 2016, with increases ranging from 6 percent to 58 percent (Stone et al., 2018). In the 27 states where veteran suicide rates could be ascertained, 17.8 percent of those who died by suicide were veterans. When Colston was an intern at Walter Reed Medical Center in 1999, the suicide rate within DoD was about 10 per 100,000. Eighteen years later, the suicide rate in DoD had roughly doubled, and the rates among reservists and Air and Army National Guards were even higher. “Suicide is the number one killer of active duty service members right now,” Colston said. “It is a huge public health problem and one that we have, despite a lot of resources and real passion, failed to get on top of.”

DoD and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) oversee populations that are predominantly male, Colston acknowledged. But in 1999, even with an 85 percent male population, the DoD suicide rate was lower than in the civilian population. Since then, the demographics have remained fairly constant, yet the increase in suicide “has been discouraging, to say the least.” A rare encouraging sign is that the rate has not changed in 6 years, after a precipitous increase in the late 2000s. “We’re stable, but we’re stable and high.”

Based on clinical experience and the existing evidence, Colston pointed to the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and other cognitive and problem-solving therapies in some groups, including in people who have engaged in self-directed violence. He also cited the effectiveness of some medications, including lithium, clozapine, and ketamine (see the previous chapter). Caring communication after hospitalization or emergency department contact is inexpensive, sensible, and buttressed by research involving home visits and follow-up contacts, he said.

Suicide is a low base rate event, is often superseded by other clinical conditions, and does not always need to be the focus of clinical concern,

Colston pointed out. He described several patients he has seen during his career who presented as being suicidal and depressed but were in fact delirious because of underlying medical problems. In this regard, he noted that the use of a single instrument can distort clinical priorities. He described his experiences with a young girl who had the prodrome of a borderline personality style and had an “alarming” score on the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale. Colston said that he thought she should undergo dialectical behavior therapy at another facility, but instead she was committed to a hospital where she could learn about other ways to engage in suicidal acts. “Whenever we think of a screening instrument, especially an instrument that’s used in isolation, we need to bring those clinical concerns to our clinical prioritization.”

Provider monitoring is evolving with technological advancements, and care and monitoring protocols could be generalized across settings, he said. For example, prescription monitoring programs at the state level are powerful tools. “We need to bring some of that capacity for provider monitoring into across-the-board treatment.”

Opportunity costs need to be assessed with any rollout, he observed, especially in primary care clinics and emergency departments. An emphasis on suicide prevention can have benefits in such settings, “but what I worry about is where the resources are going.” Could other conditions be missed?

Seamless transitions between settings and spaces are essential, he said. In addition, many people not just in clinical care but in mental health care feel that their treatments are stigmatizing and that they want to get confidential care. Or perhaps they want care from a chaplain or from the community, said Colston. “We need to find a way to make sure that we get warm handoffs between not only the clinical space but back and forth between community spaces and clinical spaces.” One way to do that is to turn everyone from a member of a universal population to a member of a selected population, such as by offering everyone in a school a cognitive behavioral therapy program.

DoD does not do much screening, but it does do a lot of outcome measures, according to Colston. Without good evidence on the usefulness of screening, this focus on outcomes is “a sensible thing,” he said. For example, a focus on outcomes in a behavioral health data portal allows outcome measures to be validated and subsequent care to be standardized and optimized.

DoD offers care, including psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers, in operational units and in primary care clinics. Colston also called attention to a recent randomized controlled trial showing that enhanced treatment as usual (E-TAU) was equivalent to Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicide (CAMS) in a suicide cohort. “I have a sense we’re doing some of the right things,” Colston said.

Colston cited the study by Lubin et al. (2010) that showed a decrease in suicide rates after a policy change that reduced access to firearms in adolescents in the Israeli Defense Forces. The study functioned as a randomized controlled study with equivalent intervention and control groups. “In essence, they took the weapons away from the kids on weekends. The suicide rate stayed the same during the weekdays, and it went down on the weekends. It was a powerful message about controlling access to guns.” The intervention, however, was delivered in an optimized setting, which limits its generalizability. In addition, Israel does not have easy access to weapons in its civilian population and weapon owners are trained to safely store and use their weapons. The United States, in contrast, is “awash in weapons,” and even though the DoD population is prescreened for mental health conditions prior to entry, the availability of guns offsets that advantage. “Of course, there are constitutional protections around weapons ownership and a number of bigger political issues that come up again and again.”

The vast majority of this problem must be addressed in a universal setting, Colston concluded. The list of community stakeholders in a military setting is wide, and this is a community-based problem. DoD does have the means to succeed in community-based interventions. For example, its opiate overdose death rate is one-quarter of the civilian rate, and its rate of opiate use disorder rate is probably one-tenth of the civilian rate. “The solution is leadership,” said Colston, “so we have zero tolerance around use.” In addition, the military has a focus on pain control, has good law enforcement, and has a force with “a smaller suite of civil rights than your civilian population does.”

Even as research proceeds both within the military and outside it, program evaluations and reviews of the evidence base are essential, said Colston, and strategy revisions should stem from these efforts. “We need to look at programs that aren’t working, and we need to create a ‘stop doing’ list, because clearly we’re doing a number of things in suicide prevention right now that aren’t working.”

“First do no harm,” Colston said. Though the evidence base is thin for postvention, it can do harm, he insisted, if people talk about the means of death or memorialize the setting in which a person died. “Those are things that we really need to look at.”

Colston suggested emphasizing the biggest moving parts with resources and efforts, including access to weapons, and then moving on to the 1 percent group. From a systems viewpoint, it is difficult to manage 80 separate problems simultaneously, he said.

A PUBLIC HEALTH STRATEGY TO REDUCE SUICIDE AMONG VETERANS

Keita Franklin, national director of suicide prevention for the Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention in the VA, put the prevalence of suicide among veterans in a somewhat different context. Of the 123 Americans who die on average each day by suicide, 20 are veterans, including 1 to 2 active duty service members. Of these 20 veterans, 6 have been receiving care from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) before their death by suicide, and 14 have not. (Overall, roughly half of veterans receive health care through the VHA and half do not.) Besides improving on the 6 veterans per day who die by suicide despite the best efforts of the VHA, “we have to work outside our system,” said Franklin. “Our charge is to prevent veterans’ suicide among the whole 20 million population.”

Franklin listed several characteristics of veteran populations at increased risk:

- Over age 50

- Women

- Survivors of military sexual trauma

- In a period of transition

- With serious or chronic health conditions

- With exposure to suicide

- With access to lethal means

Of these populations, she noted, the largest in size is veterans over age 50, but the highest suicide rates are among 18- to 34-year-olds. She also called attention to veterans who are in periods of transition, including the period right after leaving the military. To reduce the difficulties of this period, the military has made progress with a transitional program to prepare veterans for career readiness. “They know how to dress for success and they know how to interview properly,” she said. But “questions remain about whether or not they know how to adjust to the social aspects of no longer wearing the uniform. . . . Periods of transition are rocky.” DoD research has been studying the first year after leaving the military, and this research is now being extended to years 2 through 5, with the initial results being prepared for release at the time of the workshop.

Franklin listed these risk factors for suicide:

- Prior suicide attempt

- Mental health issues

- Substance abuse

- Access to lethal means

- Sense of burdensomeness

- Recent loss

- Legal or financial challenges

- Relationship issues

Franklin also listed protective factors for suicide:

- Access to mental health care

- Sense of connectedness

- Problem-solving skills

- Sense of spirituality

- Mission or purpose

- Physical health

- Social and emotional well-being

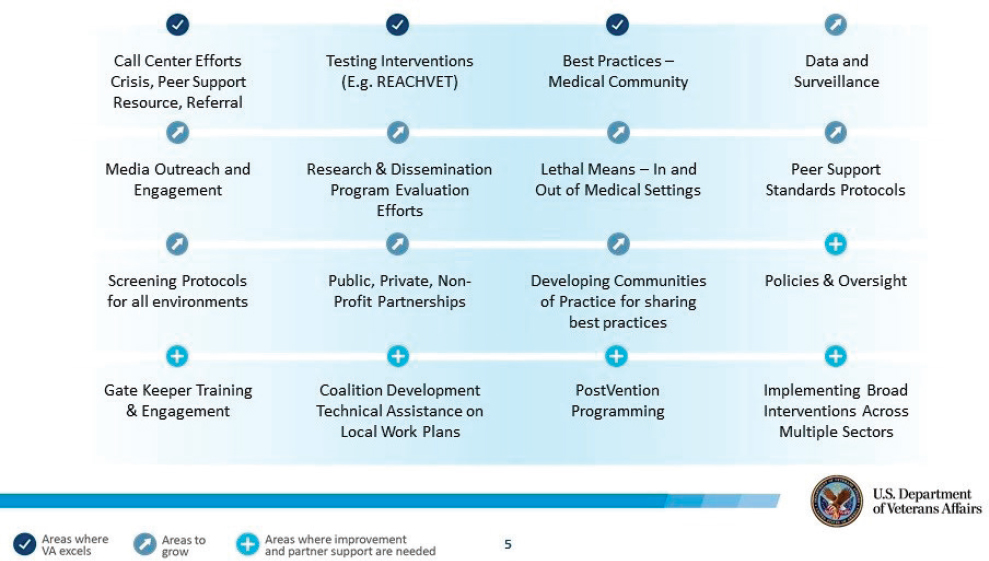

To minimize the risk factors and boost the protective factors, the VA is moving beyond a hospital-based model to a comprehensive public health approach. As Franklin described, it has developed a very broad public health strategy to reduce suicide, drawing on a wide range of social science. It incorporates health, psychology, sociology, criminal justice, spirituality, and business (see Figure 4-1). “We’re trying to draw public health activities and actions that are measurable and build a more robust evidence base for broad public health strategies,” Franklin said.

As part of this strategy, it has adopted universal, selective, and indicated prevention efforts. For example, its universal interventions include the establishment of critical partnerships, public service announcements, and social media campaigns. Its selective interventions include a mental health hiring initiative, lethal means safety training, mental health care for other than honorably discharged veterans, an executive order to expand veteran eligibility for mental health care, “telemental” health, and Veterans Crisis Line information printed on VA canteen receipts. Its indicated interventions include discharge planning and follow-up enhancements, expansion of the Veterans Crisis Line, and postvention follow-up care for family members and friends of someone who has died by suicide.

An important question for a health care provider to ask is “Are you a veteran?” Franklin observed. That question can open the door to someone getting into the right care channels. Franklin said:

There’s no wrong door for care. I don’t want you to think the takeaway is that we’re trying to singularly identify those at risk and bring them into our system alone, because we’re not. We’re thinking, if they’re at risk, we want them to get care where they want to get care, and of course the best care possible.

NOTE: REACHVET = Recovery Engagement and Coordination for Health–Veterans Enhanced Treatment.

SOURCE: Presented by Keita Franklin on September 11, 2018, at the Workshop on Improving Care to Prevent Suicide Among People with Serious Mental Illness.

A recent study found that those in VA care do better than their counterparts in non-VA care (Price et al., 2018). “But if we can get them into some sort of system of care that’s good in quality and meets the standards of all things you would expect for your own family member for care, that’s what’s important.”

Franklin discussed in more detail the Recovery Engagement and Coordination for Health–Veterans Enhanced Treatment (REACH VET) program, which uses data to identify veterans at high risk of suicide, notifies VHA providers of the risk assessment, and allows providers to reevaluate and enhance veterans’ care. Those engaged in REACH VET have more health care appointments, fewer inpatient mental health admissions, and lower all-cause mortality, she said.

The VA has recently published a National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide 2018–2028,1 which notes that clinical and community-based programs and providers have a critical role to play by screening veteran patients for mental illnesses and alcohol misuse, routinely assessing vet-

___________________

1 The strategy is available at https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/strategy.asp (accessed November 27, 2018).

eran patients’ access to lethal means, getting educated on military culture and veteran-specific issues and risks, linking veterans in crisis with appropriate services and support, and communicating and collaborating across multiple levels of care. It is not the VA’s strategy but a national strategy for preventing veterans’ suicide, she emphasized. It calls for “meeting veterans where they live and thrive. We will come to you and, and we will bring capabilities to bear for you.”

The VA also provides a spectrum of forward-looking outpatient, residential, and inpatient mental health services across the country. The VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Guidebook highlights information on these services and related programs that address the mental health needs of veterans and their families.2 In addition, the VA has a community provider toolkit with free online training for veterans issues, including military culture, for health care providers.3 It has a suicide risk management consultative program that provides free consultation for any provider who serves veterans at risk for suicide.4 In collaboration with PsychArmor, the VA has prepared a 25-minute basic training that people can take online.5

The Veterans Crisis Line and the Military Crisis Line have been expanding and have been getting about 2,000 calls per day, with 60 to 70 saves being made each day, said Franklin. “They’re doing extraordinary work. They’re also trying to leverage peer support in doing that and thinking through the way ahead in this space.” One effort, for example, has been to have veterans post risks online.

FACTORS SPECIFIC TO MILITARY SERVICE MEMBERS AND VETERANS

In response to a question from Allison Barlow, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian Health, about why suicide rates are going up, Franklin said that half of the people in active duty who end their life by suicide have a diagnosed mental health or substance abuse problem, but half do not, though behavioral health autopsies find other stressors, such as relationship, financial, or workplace problems. Roughly the same split appears to occur among veterans, she said, though the stressors may

___________________

2 The guidebook is available at https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/about/guidebook.asp (accessed November 27, 2018).

3 The toolkit is available at https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/communityproviders (accessed November 27, 2018).

4 The program is available at https://www.mirecc.va.gov/visn19/consult (accessed November 27, 2018).

5 The video is available at psycharmor.org/courses/s-a-v-e (accessed November 27, 2018).

be different in an older population. That is why interventions need to be “both and,” she said, since the risk factors for suicide are varied.

She also noted that of the 20 who die by suicide, 1 to 2 are active duty but between 3 and 4 are nonfederally activated National Guard, such as firefighters or emergency responders. Colston elaborated on this by noting that the Guard population includes people who have had military training and know how to use weapons. They have a higher suicide rate than active duty or reserved personnel, “so I’m very concerned about that population and how we reach out to them and get them services.” Many members of the National Guard have more tenuous economic lives, he noted, “they’re struggling as they move from job to job and among activations.” They have a smaller suite of social supports than regular Army members. But the secular trend in suicide is still not well understood, he noted, much less the trend within the military. Contagion appears to be playing a part, “but we don’t have a good enough understanding.”

He added that stigma is still “a huge issue and one that we haven’t done well enough on.” For example, the fear that soldiers will lose their security clearances because of a mental health diagnosis is prevalent, though this happens very rarely.

In response to a question about whether the attributes of military personnel or veterans have changed over time—for example, after 9/11—Colston noted that the Defense Manpower Data Center collects extensive demographic data, and the trend has been toward military personnel who are more educated and have fewer problems than in the past. The population is still 85 percent male and 15 percent female, as it was in 1999. Integrating females into more roles would reduce the suicide rate in the military, he noted, because the rate is lower in females than in males. He also noted that people wanting to join the military can get waivers for many medical conditions, including mental conditions, and that people who have waivers do just as well as those who do not have them. The more important issue, he thought, is to separate out people in initial training who probably will not do well in the military, which he noted is less common than it used to be. “We used to separate 4,000 people a year for personality disorders; we now separate 300 a year, so the sense is we can retain and treat, [though] I don’t know that we’re doing all that well on that.”

PROVIDER TRAINING, NEEDED SERVICES, AND ACCESS TO CARE

In response to a question on training providers to provide effective care for people with suicidality, Franklin observed that surveys have shown that roughly 60 percent of people across multiple health care professions reported that they were not prepared to engage with suicidality. Given that

suicide has a low base rate, they should not be expected to use these skills frequently, but they need to have the skills when necessary, said Franklin. Training needs to be “appropriately resourced” so it is not “one and done.”

She also cited the need to engage veterans’ family members as gatekeepers. If they know the signs and symptoms of suicidality, they can help get someone into care. “We’ve not done enough on that side of it.”

Colston cited the need for community-based services in addition to clinical services. Of course, comorbid mental health conditions need to be treated, because, as he said, “as a clinician I never see someone who is suicidal who doesn’t have a comorbid mental health condition.” But suicide can occur in the absence of such a condition, as with adjustment disorders in adolescents that can lead to sudden decisions. At the same time, he warned, both clinical and community-based services need to be evidence based to ensure they are effective.

In response to a follow-up question about how to reach veterans who are not receiving care through the VHA, Franklin advocated a “whole of government” and “whole of industry” approach. “We have to leverage the nation around this problem.” A good example is the mayor’s challenge work going on with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), which has brought together the VA and SAMHSA in eight cities to take broad public health approaches with careful evaluations to track outcomes over time. Such studies can reveal whether the best approach is using public health to get people into a clinical environment or whether broad support for public health will make a difference in and of itself. For example, some people may only be willing to go to their church for support. “Might that be okay as the end solution, or is it up to the church to then get them into a clinical setting?” Colston picked up on that point, observing that chaplains have to know how to render mental health care. He also reiterated the value of the crisis lines, which are a good way to reach people who are not getting medical care. The effects of such interventions need to be studied much more carefully, he acknowledged, saying:

We can’t live without those. Those lines are giving care right now to people who either think that the care that they get is too stigmatizing or who we can’t match well with someone who can help them.

Michael Schoenbaum, senior advisor for mental health services, epidemiology, and economics in the Division of Services and Intervention Research at the National Institute of Mental Health, asked about the logistical and policy issues associated with identifying veterans who are not receiving care from the VHA and transferring them into the VHA system, to which Andrew Sperling, director of legislative advocacy for the

National Alliance on Mental Illness, added a question about veterans who have received a less than honorable discharge. Both Franklin and Colston noted that checking whether someone who claims to be a veteran actually is a veteran and qualifies for benefits is difficult to do in health care institutions, though a new VA policy is seeking to facilitate this identification. The VHA also offers crisis stabilization for those who have less than honorable discharges. This group is particularly at risk, noted Franklin, yet few come to the VHA system for help. “We have more work to do on marketing and outreach to make sure people know that they’re able to come in,” she said. “If people have left under other than honorable, they can get care at no cost and we’ll stabilize them and help them.”

REFERENCES

Lubin, G., N. Werbeloff, D. Halperin, M. Shmushkevitch, M. Weiser, and H. Y. Knobler. 2010. Decrease in suicide rates after a change of policy reducing access to firearms in adolescents: A naturalistic epidemiological study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 40(5):421-424.

Price, R. A., E. M. Sloss, M. Cefalu, and C. M. Farmer. 2018. Comparing quality of care in Veterans Affairs and non-Veterans Affairs settings. Journal of General Internal Medicine 33(10):1631-1638.

Stone, D. M., T. R. Simon, K. A. Fowler, S. R. Kegler, K. Yuan, K. M. Holland, A. Z. IveyStephenson, and A. E. Crosby. 2018. Vital signs: Trends in state suicide rates—United States, 1999-2016 and circumstances contributing to suicide—27 States, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67(22):617-624.

This page intentionally left blank.