Another population discussed in detail at the workshop was Native Americans and Alaska Natives. As with veterans, these groups have many distinctive attributes, but experiences with effective suicide prevention programs in these groups also bear lessons that apply to all groups.

UNMET NEEDS AMONG NATIVE AMERICANS AND ALASKA NATIVES

Much can be learned from Native American and Alaska Native communities about how to prevent suicide, said Allison Barlow, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian Health, despite some of the complications that surround the study of these groups. Rates of suicide are much higher among American Indians and Alaska Natives compared with other populations in the United States, but these groups also exhibit great regional differences in mental health and suicide. American Indians and Alaska Natives typically have poor access to mental health services, and epidemiological data on serious mental illness are very incomplete for these groups. In addition, Native groups have cultural differences in understanding mental illness and mental health promotion, which contribute to differences in patterns of suicide. All these factors point to the need for tailored strategies of suicide prevention among Native Americans, said Barlow.

The Indian Health Service (IHS) is responsible for providing essential medical and mental health services for approximately 2 million American Indians and Alaska Natives who are eligible for these services. At least 3 to 4 million other American Indians and Alaska Natives living in urban areas

are not covered by the IHS, though they might be covered by Medicare or Medicaid. Historical traumas, including forced relocations and cultural assimilation, broken treaties, and other social, economic, and political injustices have helped to create large behavioral and mental health disparities for American Indian and Alaska Native communities, Barlow observed.

As with other groups, the suicide rate among American Indians and Alaska Natives has been increasing since 2003. In 2015, their suicide rates in 18 states participating in the National Violent Death Reporting System were 21.5 per 100,000, more than 3.5 times higher than those among the racial or ethnic groups with the lowest rates. Suicide is the second leading cause of death behind unintentional injuries for Indian youth ages 15 to 24 residing in IHS service areas and is more than three times higher than among the general population. “The years of productive life loss for those communities is astounding,” said Barlow. Natives experience serious psychological problems more than the general population, with the most significant mental health concerns being high prevalences of anxiety, depression, substance use, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Though effects of historical trauma on serious mental illness are unknown, American Indians and Alaska Natives experience PTSD at twice the rate of the general population. Men have high alcohol dependence rates compared with other populations, and women have higher depression rates. Furthermore, many of these mental health needs remain unmet, with at least seven times the level of unmet needs in some Native populations for certain illnesses compared with the general population. As a specific example, Barlow pointed to a study of parents revealing much higher rates of serious mental illness among American Indians and Alaska Natives (Stambaugh et al., 2017). “When you think about historical trauma compounded by intergenerational transmission of serious mental illness, we have a huge problem in tribal communities.”

Finally, these communities have a critical shortage of qualified treatment providers, especially for children and adolescents, said Barlow. Some regions have no psychiatrists, psychologists, or social workers taking care of tribal community members. In other regions, providers often become overwhelmed by the continuous demand for services, resulting in large vacancy rates. “This gives you some background” of the problems facing Native communities, Barlow said.

CULTURALLY TAILORED INTERVENTIONS IN ALASKA NATIVE COMMUNITIES

Universal prevention efforts need to be part of the mix of an effective response to the public health crisis of suicide in Native communities, said James Allen, professor in the Department of Family Medicine and

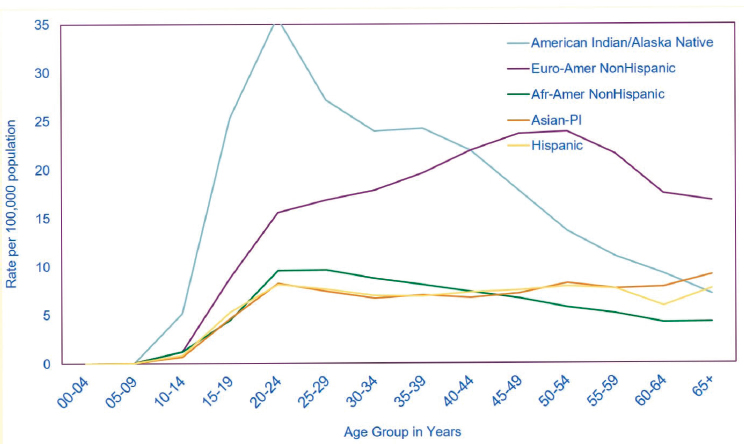

Biobehavioral Health at the University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth campus. Suicide is different among Native communities compared with other racial and ethnic groups. It peaks in adolescence and young adulthood and falls thereafter, rather than staying stable or rising over time (see Figure 5-1).

Suicide in Native communities “calls for a different approach,” said Allen. “That’s why culture matters.”

Allen does most of his work in Alaska, where age-adjusted suicide rates are about 40 per 100,000 people, versus about 18 for Alaska non-Native populations statewide and 14 for the white population across the United States. Suicide is also much more common among Native males, who have a suicide rate that exceeds 60 per 100,000 people in the state. However, Native culture in Alaska exhibits great geographic, language, economic, environmental, and historical diversity, and the suicide rate varies as well by region and within regions. “Suicide is not a problem of Alaska Native people,” Allen observed. “It’s a problem for some Alaska Native people.”

Alaska Natives also share many social determinants of health, including marginalization, intergenerational trauma, and rapid involuntary change, along with culturally distinctive protective factors. Some communities have not had a death by suicide for 30 years, while others have seen waves of

NOTE: Afr-Amer = African American; Euro-Amer = European American; PI = Pacific Islander.

SOURCES: Presented by James Allen on September 11, 2018, at the Workshop on Improving Care to Prevent Suicide Among People with Serious Mental Illness. Data provided by Alexander Cross, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014, used with permission.

suicide. This emphasizes the need to think about the communities and populations at risk, Allen said.

Allen and his colleagues have been working in Yup’ik communities in Alaska to develop an Alaska Native toolbox designed for local community adaptation. Known as Oungasvik, the toolbox makes use of a traditional model of social organization known as Qasgiq that seeks to grow protective factors contributing to reasons for life and sobriety (Allen and Mohatt, 2014; Allen et al., 2018). Allen showed a video at the workshop that outlined the basic features of the Qasgiq model, which he said is “built around the concept of how do you bring a community together again.”1 It is not a risk reduction approach; rather, it promotes protective factors in young people through a multilevel intervention in families, communities, and individuals.

As an example, Allen briefly described an implementation strategy for a community-level change process. In traditional Yup’ik culture, the Qasgiq was a house where all the men lived that provided a central place for community gatherings, ceremonies, and celebrations. Today, the Qasgiq model provides a framework for bringing people together with traditional teachings and values to address contemporary challenges. The idea is that “I can solve my problems by seeking out others in my social environment to assist me in solving them,” Allen said. By emphasizing community, the model “becomes very culturally patterned and grounded in local cultural beliefs.” Research has demonstrated that the targeted protective factors function as predictors of the intervention’s two ultimate variables: reasons for life, and reflective processes about the consequences of alcohol consumption or reasons for sobriety (Allen et al., 2014). Community-level factors are the strongest predictors of outcomes, and higher levels of interventions exhibit higher levels of protection.

Effective suicide prevention is culturally tailored to the population it serves, Allen concluded. Culture provides protective factors as tools for prevention, and cultural practices provide effective implementation strategies.

SUICIDE PREVENTION IN THE WHITE MOUNTAIN APACHE TRIBE

The White Mountain Apache tribal community includes about 17,000 tribal members in central-eastern Arizona. They are geographically isolated, have a spectrum of traditional and mainstream cultures, and are governed by an 11-member tribal council that has just selected its first chairwoman. The community has had a 38-year relationship with the Johns Hopkins

___________________

1 The video can be viewed at http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/MentalHealth/SuicidePreventionMentalIllness/2018-Sep-11/Videos/Panel-4-Videos/20-Allen-Video.aspx (accessed November 27, 2018).

Center for American Indian Health focused on infectious disease, behavioral and mental health, and training programs. Barlow described some of the work the center and the tribe has done on suicide prevention, especially as it relates to tribal-specific data and tribal sovereignty.

As in other Native American and Alaska Native populations, suicide rates prior to 1950 were very low and then started to rise, with spikes in youth suicide in the late 1980s that have continued until the present. The community has a variety of strengths that it has brought to bear on this problem. It has tribal sovereignty, which provides a degree of autonomy over legislation related to tribal governance. Families are the center of culture, and large family networks strengthen the community. Traditions support the sacredness of life and youth, and the community has a strong capacity to adopt, adapt, and diffuse innovations.

In response to the rise of suicide, in 2001 the tribe mandated a suicide surveillance and registry system. The first registry was a paper-and-pencil reporting system with limited follow-up and financial resources. In 2004, the tribe asked the Center for American Indian Health to help develop a computerized registry management system that could make quarterly reports and help plan responses to ongoing trends. The system has evolved greatly since then, said Barlow, and today all community members, including schools, departments, and individuals, are responsible for reporting individuals at risk for any self-injurious behaviors.

Reportable behaviors include suicide death, suicide attempt, suicide ideation, nonsuicidal self-injury, and binge substance use. These behaviors are followed up on by a team called Celebrating Life. They make a referral, based on the preferences of those individuals, to local services, which can range from local behavioral mental health services to traditional healers to churches. The local case managers started as paraprofessionals and have continued their professional development, with two now enrolled in a Ph.D. program at Arizona State University, so “It is a ladder for development,” said Barlow.

The surveillance data showed an average suicide incidence rate of 40 per 100,000 people per year, which is comparable to the rate in Alaska. However, among young people ages 15 to 24, the rate was 130 per 100,000 people, or 13 times the U.S. average. The highest death rates were for 20-to 24-year-olds, and the highest attempt rates were for 15- to 19-year-olds. Males accounted for six times as many deaths by suicide as females, but their attempt rates were similar, which is different from the patterns in the general U.S. population, noted Barlow, where females attempt suicide at three times the rate of males.

To gain a deeper understanding of the precipitants of suicide attempts, Apache research staff conducted a one-time, in-depth, quantitative assessment battery of 71 youth ages 10 to 19 who recently attempted suicide,

with a subsample participating in year-long qualitative interviews. “We didn’t find anything really incredible or remarkable,” reported Barlow. The subset of youth who participated in the diagnostic interview reported higher levels of separation anxiety, agoraphobia, conduct disorder, alcohol dependence, and marijuana dependence. When asked about their reasons for attempting suicide, 35 percent cited family problems, 19 percent said they were angry or depressed, 16 percent said they had relationship problems, 15 percent said they had a recent suicide or death of another person, and 22 percent simply said “nothing,” which occurred most often when someone woke up from an alcohol or drug use binge and could not remember having attempted.

Of the youth who attempted suicide, 64 percent were referred to local behavioral health systems, but only 60 percent of those attended. “That means that less than 40 percent of the total who attempted ever got any medical health care,” noted Barlow.

Suicide and substance abuse overlap extensively in Native deaths by suicide. Of those who died at ages 10 to 25, 68 percent were drunk or high at the time, and the percentage could be much higher, since the alcohol and drug use of the others was largely unknown. Of those who attempted suicide, 44 percent were drunk or high, and that was not their primary method. Many of the suicide deaths in this community are by hanging, Barlow observed, which implies that means restriction is not a good public health solution in this community. Impulsivity and reactivity were common among those who attempted suicide: “It just happened out of nowhere.” “I didn’t really think about it, I just took off and tried to look for that rope.” Family dynamics and substance use were other frequent themes: “Our relationship is a boat, and it’s got holes in it.” “I always stayed with my grandma. I only wanted to be around my mom when I knew she was trying to quit. And it wasn’t that long before she would take off and drink more.”

Since 2001 the tribe has expanded the mandate for reporting, which has shaped its prevention methods, Barlow said. The resulting Celebrating Life prevention program has universal, selected, and indicated components. The universal component includes community-wide education to promote protective factors and reduce risks. The selected component includes early identification and triage of high-risk youth. The indicated component includes intensive prevention interventions with youth who attempt suicide and their families.

As more detailed examples, Barlow listed the following activities under the program’s universal component:

- Interagency meetings

- A public education multimedia campaign

- Suicide prevention walks

- Suicide prevention conferences

- Door-to-door campaigns

- Booths at health and tribal fairs

- Regular distribution of lifeline cards

Selected and indicated activities include caretaker trainings, cultural and strength-based activities led by elders, a middle school curriculum taught monthly by elders, elementary school workshops, and field trips. Two brief interventions of 2 to 4 hours are designed to reduce imminent risk and connect to care with a video and curriculum entitled “New Hope”; these interventions now also target substance abuse.

These interventions have had a major effect. From 40 per 100,000 people in the period of 2001–2006, the suicide death rate among the White Mountain Apache Tribe dropped to 24.7 during the period 2007–2012, a 38 percent drop (Cwik et al., 2016). “Comprehensive prevention approaches appear to be helping and working,” said Barlow. But serious concerns remain. For example, young women, especially young mothers, seem to be at increasing risk. “This is a huge worry for the tribe.” Continuing to build on the strengths of the community will be the key to further progress, she concluded.

SUICIDE PREVENTION IN SOUTHCENTRAL ALASKA

Alaska has the highest rate of suicide in the nation, noted Jennifer Shaw, a senior researcher at Southcentral Foundation. Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death nationally, but it was the fifth leading cause of death in Alaska in 2015. Between 2000 and 2009, of 281 communities in Alaska, at least 1 suicide occurred in 179. With a population of just 740,000 people—17 percent of whom are Alaska Natives or American Indians—there were 200 deaths by suicide in the state in 2015, and 32 percent of those deaths were among Alaska Natives and American Indians.

Reducing the incidence of suicide is among the family wellness corporate initiatives of the Southcentral Foundation, which is one of 12 regional Native corporations and health centers in Alaska. An Alaska Native–owned and Native–operated health care system serving 65,000 people in the greater Anchorage area and 55 rural villages, the Southcentral Foundation covers a region of 107,000 square miles, from the Canadian border to Anchorage to portions of the Aleutian Islands. The vision of the Southcentral Foundation, which recently won its second Baldrige Award and hosted the Surgeon General at its primary care center, is “a Native community that enjoys physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual wellness,” and its mission is to “work together with the Native community to achieve wellness through health and related services.” The people other

systems would call “patients” it calls customer-owners who have a shared responsibility for health and wellness.

The Southcentral Foundation emphasizes integrated care teams in which a primary care provider works alongside a nurse case manager, certified medical assistant, dietitian, and behavioral health consultant with colocated psychiatry and pharmacy services. Behavioral health care services comprise about 13 specialty programs, including outpatient services, residential treatment for substance use issues, treatment for adults with serious mental illness, intensive case management, and behavioral health aides. The system is supported by a strong data collection and analysis process, and it has an independent research team that is largely federally funded.

The Southcentral Foundation has taken a number of steps to address the suicide crisis within the communities it serves. It has established a behavioral urgent response team (see “Overcoming Barriers to Treatment” in Chapter 6), has integrated behavioral health into primary care, has organized a depression collaborative, has instituted a suicide prevention plan, and has signed a memorandum of understanding with the state of Alaska to share suicide data. In addition, specific services are focused on suicide prevention, including the Quyana Clubhouse, which integrates primary care with behavioral interventions, colocated and integrated care in shelters for adolescents and adults, a specialized suicide prevention intensive case management program called Denaa Yeets’, traditional healing, and complementary medicine.

The Southcentral Foundation uses telemedicine heavily to provide services to its 55 rural communities, Shaw noted. Telemedicine also lends itself to the caring contacts approach, which focuses on making people stronger and more connected and can be delivered cheaply over distances. “It doesn’t require people to travel hundreds and hundreds of miles when they’re in crisis,” she said. “We can prevent that by providing care when they’re at home.” Telemedicine also is an important part of workforce development, because it allows providers such as community health aides, behavioral health aides, and dental health aides to stay in their home communities.

The research done by the Southcentral Foundation on suicide prevention is largely clinical and focused on the population it sees in the health care system. It is testing a culturally tailored version of caring contacts with three other tribal sites in the lower 48 states, with the Alaska site being the largest in the study. It was planning to apply a predictive algorithm developed by the Mental Health Research Network to determine whether the algorithm can be validated with a smaller population or whether a population-specific algorithm is needed. The foundation also is thinking about the ethics as well as the logistics of applying such an algorithm, which is a “question that we need to start addressing as a community of researchers and practitioners.”

Shaw listed a number of challenges the system faces, including early detection and identification of individuals in need of care; the availability of resources (as she pointed out, “jail is not suicide prevention”); integration between electronic health records, care coordination, and dual diagnosis; continuous coordinated engagement of high-risk individuals; the lack of culturally appropriate, acceptable, and owned interventions; and insufficient funding and scientific support for building a culturally driven evidence base.

She concluded by describing some of the lessons emerging from the foundation’s work in Alaska. One is that “trust must come before treatment. Whether you’re doing community-based work or clinical work, the relationship is the basis for any healing process or intervention or prevention that’s going to happen,” particularly with communities that have experienced historical trauma, mistreatment, and maltreatment by researchers as well as clinicians. Communities need to be engaged as partners, teachers, and researchers, she said, while also working on capacity building. In the research department in which Shaw works, 70 percent of the staff are Alaska Native or American Indian, and two of the Native master’s-level researchers recently started Ph.D. programs while one was headed to medical school. “Although I’m not a Native researcher, I hope that someday I can put myself out of a job.”

Finally, interventions need to be targeted at all levels of human experience, respect autonomy, and honor community, she said, which requires they be tailored to or developed from within local cultures and patterns of being, communication, and relationships.

SUICIDE PREVENTION IN MINNESOTA

“The community that I am working in is ground zero for the opioid epidemic in Minnesota,” said Laurelle Myhra, director of behavioral health at the Native American Community Clinic (NACC), who discussed suicide prevention efforts among the Red Lake Nation in Northern Minnesota. Minnesota Natives are five times more likely to die from a drug overdose than their white counterparts, disparities that are linked to the intergenerational effects of historical trauma and cultural genocide and a lack of access to Native providers and culturally specific trauma-informed care. In the past, grandmothers or other family members might have stepped up when a parent was struggling with alcohol use. “What we are seeing now, with the opioid epidemic, is that families are using together,” said Myhra.

When someone comes to the clinic, whether for dental, medical, or behavioral health, the clinic screens for depression, suicidal ideation, anxiety, and other conditions. It then rescreens those with depression and suicidal ideation on a regular basis. A behavioral health provider is available

for medical and dental visits “or, if they are not willing, a spiritual care person.” The clinic has an elder in residence full time who can provide that service or serve as a care coordinator. The elder in residence has started an elder council that reviews policies and procedures and looks for ways to improve planning and care. Those coming out of emergency services receive monitoring and supportive care, and electronic records are available to coordinate care. “Our care coordinators are seen as part of the community,” said Myhra. “They work with people’s families for years and have a strong connection. That’s a real strength.”

The clinic has an outpatient behavioral health program that also serves as a training program to build workforce capacity. A peer support recovery program is embedded within the program, and the clinic is working toward certifying and being able to pay the peers. Safety plans include provisions for opioid overdoses. Even when someone is not identified as having suicidal ideation, multiple overdoses call for both a safety plan and care planning and coordination, said Myhra. The clinic seeks to engage families in support and safety planning, and it connects to community supports and events such as ceremonies.

Through partnerships, the clinic has sought to expand access to culturally sensitive and trauma-informed services. One of the most long-standing of these partnerships, with the White Earth Tribe in Minnesota, has been a medication-assisted treatment (MAT) program that includes a clinic prescriber and wraparound services provided through the clinic. This program has been adopted by the tribe as a recovery model, said Myhra. “When people hear that their family members are getting involved in MAT, they get very excited about that and really want to be supportive. That is something different than I’ve observed in other communities.”

Another partnership involves an intensive outpatient program in an impoverished part of Hennepin County, Minnesota. In response to specific gaps within existing culturally specific programs, the partnership works with families and the community to build on existing strengths, to “develop something for those who are in the margins.”

In more distant regions where recruiting providers is difficult, telehealth programs are providing diagnostic assessments to people in shelter programs and children’s programs. This partnership allows for billing for supportive services such as spiritual care, which has helped with the program’s sustainability. In other cases, billing is a major problem, Myhra said. For example, as a federally qualified health care center, the clinic cannot bill for services provided offsite.

Health equity is a major consideration in all the clinic’s programs, said Myhra. In addition, meeting the needs of the community requires workforce development, including the training of behavioral health providers, community health workers, and people who can provide peer support. “If

we want these providers to be Native American and from the community, we are going to have to train them ourselves, so that’s the effort and model that we are moving toward.” Finally, meeting needs requires adequate funding, which means asking whether the existing funding is reaching the people most in need.

WORKFORCE PREPARATION

Following up on Myhra’s final point, a question about the linkage between care for serious mental illness and suicide prevention focused on workforce development, and specifically on the preparation of people within particular communities to address these issues.

Shaw emphasized the need to start “early, early, early” in building a workforce, well before young people graduate from high school, “because many of these kids are going to be the first in their family to ever leave their family or their village and go to college.” She also cited college programs that can direct young people into health care, such as the Alaska Native Science and Engineering Program at the University of Alaska, which sends some graduates to medical school. “Nontraditional” pathways, which are actually traditional in Alaska, are another route to providing health care services. These should be validated using scientific tools and techniques, Shaw urged, so that a growing evidence base can allow them to be funded. “That’s going to be a long uphill battle, but those of us who are non-Native researchers and stakeholders have a big role to play in fighting that battle.”

Myhra pointed out that many of the evidence-based protocols used in these communities originate in indigenous knowledge. “We have the knowledge within the community,” she said, “but we need structures in place to bill for those.”

Allen pointed out that each of the projects discussed by the panel also has a capacity development component. “That’s part of the picture,” he said. “The solutions are within.” Communities have cultural knowledge and a past history of success, and local people have the credibility, the cultural understanding, and the trust of the community. “Beginning with that is crucial to being an effective provider.”

Finally, Barlow observed that no community in the United States can afford to wait while its treatment needs pile up. “Right now we have great opportunities for early childhood intervention that are intergenerational,” she said. “We know that the risk and protective factors start then when someone is pregnant and the family is forming.” The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is still supporting home visit interventions. In addition, public health nurses and community health representatives can advance suicide prevention, though legislation has been proposed to eliminate community health representatives, “which would be a tragedy.” Federal funding

streams are supporting these different levels of the workforce and their integration into mental health systems. “That’s the future for all communities.”

CASE IDENTIFICATION AND MANAGEMENT

In response to a question about the identification and management of individuals who are at high risk for suicide, Barlow elaborated on the White Mountain Apache home visit program. The intention was to go to homes and schools and “meet the people wherever they are, because it was found that that was very much welcome.” When suicide deaths among young people began to rise, the behavioral health department and the Celebrating Life team decided to go door to door, which since then has become an annual event. They provide information about resources such as a suicide hotline. They also say, “if you need me now, I can stay. If you need me in the future, I can come back.”

Shaw elaborated on the Denaa Yeets’ program for people at high risk of suicide. People enroll in the program and participate in its activities while the program checks on them and on their progress. During a series of in-depth interviews with people who had experienced suicide ideation or attempts, many spoke about the critical role that the Denaa Yeets’ program played in keeping them alive.

By knowing that somebody was going to check in on them, by the connection that it provided to cultural activities, . . . to their heritage, to their people, to their community, to the things that feed their soul, [the program] was really important for people who struggled with severe anxiety, with severe depression, and all the other things that we talk about as proximal risk factors.

Lastly, Myhra observed that her clinic offers care coordination and case management through patient advocates who support people with general resources or resources specific to behavioral health care.

PUTTING A SPOTLIGHT ON PROTECTIVE FACTORS

In a final comment, Shaw noted that, while some Alaska Native and American Indian communities have high rates of alcohol and substance use, they also have high rates of abstinence. This bi-modal distribution of risk and protective factors “often gets lost in these discussions.” The same may well apply to serious mental illness, she speculated. If the counterparts to such illnesses could be identified, they likewise could be elevated as protective factors in these communities.

I went to Alaska to study suicide among youth, and I quickly realized that I wasn’t going to be able to do that as a non-Native outsider who had no relationship with the communities. But after living there for a few years, I realized that that wasn’t what needed to be studied.

The conditions of Alaska Native youth are usually so grim that their high suicide rates can seem unsurprising, she said. But “there must be something really right going on in these communities” to be raising so many children who are not just surviving but thriving. “We need to remember the other side of that coin. We need to be looking for those counter factors, . . . because that’s where we’re going to find solutions.”

REFERENCES

Allen, J., and G. V. Mohatt. 2014. Introduction to ecological description of a community intervention: Building prevention through collaborative field based research. American Journal of Community Psychology 54(1-2):83-90.

Allen, J., G. V. Mohatt, C. C. T. Fok, D. Henry, R. Burkett, and the People Awakening Team. 2014. A protective factors model for alcohol abuse and suicide prevention among Alaska Native youth. American Journal of Community Psychology 54(1-2):125-139.

Allen, J., S. Rasmus, C. C. T. Fok, D. Henry, and the Qungasvik Team. 2018. Multi-level cultural intervention for the prevention of suicide and alcohol use risk with Alaska Native youth: A non-randomized comparison of treatment intensity. Prevention Science 19:174-185.

Cwik, M. F., L. Tingey, A. Maschino, N. Goklish, F. Larzelere-Hinton, J. Walkup, and A. Barlow. 2016. Decreases in suicide deaths and attempts linked to the White Mountain Apache Suicide Surveillance and Prevention System, 2001-2012. American Journal of Public Health 106(12):2183-2189.

Stambaugh, L. F., V. Forman-Hoffman, J. Williams, M. R. Pemberton, H. Ringeisen, S. L. Hedden, and J. Bose. 2017. Prevalence of serious mental illness among parents in the United States: Results from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 2008–2014. Annals of Epidemiology 27(3):222-224.