5

Moving from Assessment to Action

The final session of the workshop’s first day focused on how the scientific findings of California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment (State of California, 2018) will inform direct actions at the state or local level, and more broadly on the role of science in shaping climate adaptation and mitigation policy as well as the role of policy in shaping science. California has been a leader nationally and globally in developing policies that drive scientific research and discovery, and likewise in translating scientific findings into new policy and planning guidance. John Wall (Cummins Inc., retired) moderated the session, commenting that he is impressed at the level of technical and policy engagement in California on climate change adaptation even absent strong regulations. Nancy Thomas (Geospatial Innovation Facility, University of California, Berkeley) described their efforts to make recently released climate science and supporting data available and accessible to researchers, practitioners, and the general public through the Cal-Adapt tool. Liz Whiteman (Ocean Science Trust) described her experience conducting a scientific assessment to inform the state’s updated sea level guidance and commented on characteristics of the assessment process that can lead to better usage by policy and other decision makers. Kristin Ralff-Douglas (California Public Utilities Commission) shared the process and motivation for the commission’s recently initiated rulemaking that will regulate climate adaptation investments by investor-owned utilities. Last, Susanne Moser (Susanne Moser Research and Consulting) reflected on 20 years of working in California climate assessments, presented an iterative framework for effective climate assessments, and shared a case study of her work with the Climate Safe Infrastructure Working Group.

MODERATOR: JOHN C. WALL, CUMMINS, INC. (RETIRED)

Wall described his experience working in emissions reduction technologies for diesel engines, noting that many of the same challenges arise in translating the latest scientific research into practice in the form of product development decisions to address sources of greenhouse gas emissions and other contributors to climate change. One important difference between climate change mitigation and diesel engine development is the established regulatory context for the latter, and he commented that these regulations were important to drive innovation and fair competition among commercial companies that in turn drove widespread change across the industry. In part this was made possible by neutral scientific organizations such as the Health Effects Institute, and Wall suggested that there could be other valuable lessons to learn from historical environmental policy challenges. He introduced the session on Moving from Assessment to Action, saying that the goal is to focus on how scientific information can move into practice and inform broader change beyond individual communities and champions.

NANCY THOMAS, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, GEOSPATIAL INNOVATION FACILITY

Thomas introduced Cal-Adapt,1 which is a web application designed to make complex downscaled climate models and information available to the public, practitioners, and decision makers who are developing on-the-ground adaptation strategies (Thomas et al., 2018). Cal-Adapt hosts data from numerous California research institutions and presents information to users through interactive visualizations that are engaging, accessible, and reproducible. She described several fundamental principles that guided development of Cal-Adapt to best provide a scientific basis for exploring climate risks and adaptation options, including integrating only rigorous peer-reviewed contributions and providing access to all primary data; presenting and explaining content in easy to understand and interpret formats that are interactive for users; and enabling development of custom tools and software. Stakeholder engagement and guidance was essential to understand user needs and develop tools that are helpful in practice, she explained.

Although originally launched in 2011, Cal-Adapt 2.0 was recently released and includes data with higher resolution and fidelity based on statistical downscaling (Pierce et al., 2018), including temperature and precipitation, sea level rise (SLR), wildfire projections, hydrological variables such as snowpack, as well as observed historical data. The default scenarios considered in Cal-Adapt are based on four priority climate models that are the basis for the Fourth Assessment and are approved by the state for energy sector planning, said Thomas, which can be more tractable for users than presenting downscaled results from more than 30 models. She briefly demonstrated several tools available on Cal-Adapt, including a heat warning tool that showed the numerous features available that allow users to export images and data, aggregate data based on existing filters such as county, city, or census track, and import their own geographic areas of interest or heat warning thresholds.

Thomas briefly described several examples of how Cal-Adapt is being used by California utilities to conduct climate vulnerability assessments through the Department of Energy (DOE)’s Partnership for Energy Sector Climate Resilience.2 Beyond vulnerability assessments, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas and Electric have each used Cal-Adapt in the planning and design of specific assets to improve their system’s climate resilience, and ultimately Thomas imagined Cal-Adapt being used in general rate cases approving utility investments. She noted that Cal-Adapt is being used outside the energy sector as well and pointed to several policy and planning documents that reference Cal-Adapt, including SB 3793 (which requires integration of climate risk in local hazard mitigation plans) and the Office of Planning and Research’s General Planning Guidelines.4

LIZ WHITEMAN, OCEAN SCIENCE TRUST

Whiteman shared her perspective on characteristics of science and the assessment process that support policy making and other actions based on her experience informing the update to the state’s guidance (State of California, 2018a) on SLR. She noted that the environment for making policy based on scientific research is very favorable in California, as evidenced by Governor Jerry Brown’s request to the Ocean Protection Council to produce a state-of-the-science report on Antarctic ice loss and its impact on SLR in California. The council worked with the Ocean Science Trust to develop this report in less than 6 months, and she noted that the first characteristic of actionable science is that it is provided at a useful time for a decision maker. They began by convening stakeholders through four regional workshops and online listening sessions to understand how local authorities and communities would be impacted by changes in statewide SLR policy and how the scientific effort informing this policy could better support their needs. Simultaneously, they created a policy advisory committee with representation from multiple state agencies to understand the information needs of policy makers and guide their assessment to answer policy-

___________________

1 State of California, California Energy Commission, “Cal-Adapt,” https://cal-adapt.org.

2 U.S. Department of Energy, “Partnership for Energy Sector Climate Resilience,” https://www.energy.gov/policy/initiatives/partnership-energy-sector-climate-resilience.

3 State of California, “Land Use: General Plan: Safety Element,” Senate Bill No. 379, Chapter 608, October 8, 2015, https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160SB379.

4 State of California, Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, “General Plan Guidelines,” http://opr.ca.gov/planning/general-plan/.

relevant questions. Both process steps were essential to framing and conducting a scientific assessment that pursued the right questions to be useful and actionable, she said.

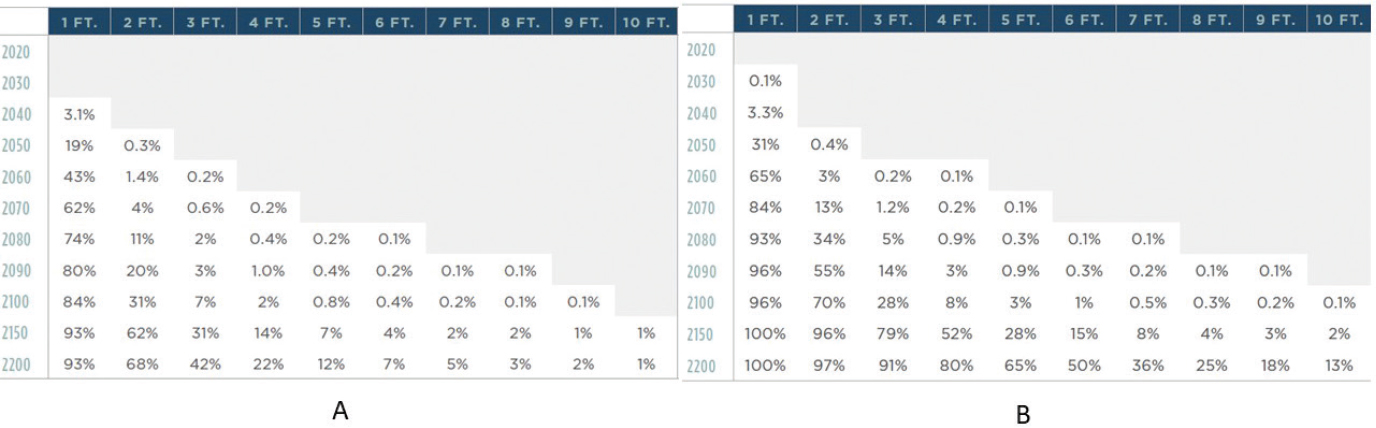

With a better understanding of policy and decision maker needs, a team of diverse scientists were convened to develop the assessment, which included climate scientists and glacier and shoreline experts as well as a statistician expert in extreme event modeling and a decision scientist focused on understanding and acting under uncertainty. Through the expert panel’s deliberations, the report presented their findings as local probabilistic projections based on various emissions pathways and tied to 12 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration tide gauges along the California coast. This both allowed more explicit treatment and presentation of uncertainty but also allowed local decision makers to more easily place their region into projections as opposed to the single state-wide projection they replaced. Whiteman explained that the panel took an additional step of translating projected SLR into formats that are easily used in risk assessments—for example, exceedance probability tables that show the likelihood that SLR will be greater than a given height at a given time—which allows decision makers to more readily integrate this new information into existing risk-based planning processes (Figure 5.1).

The assessment also included an extreme SLR scenario that was not assigned a probability but was included to capture potential effects of Antarctic ice loss that resulted in more than 8 feet of global SLR. The guidance published in 2017 (Griggs et al., 2017) provides a useful starting framework for local authorities and policy makers to consider adaptation pathways and strategies, and Whiteman concluded that the process demonstrated the opportunity and value of iterative assessments to guide science-based adaptation strategies. “Waiting for scientific certainty is neither safe nor prudent,” said Whiteman.

KRISTIN RALFF-DOUGLAS, CALIFORNIA PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION

Ralff-Douglas introduced the California Public Utility Commission’s (CPUC) recently initiated rulemaking on climate change adaptation.5 Research products from the Fourth Assessment and other state initiatives have been extremely helpful for the CPUC, and she emphasized the value of decision support tools such as Cal-Adapt and planning guidance documents such as from the Ocean Protection Council and the Climate Safe Infrastructure Planning Group established through Assembly Bill 2800.6 Nonetheless, there is much more to be learned through further research and sustained assessment activities, such as those related to direct impacts on energy supply, demand, infrastructure, and operational procedures as well as how the sector and the CPUC should respond. Assessment will continue to be needed alongside investment and regulatory actions, explained Ralff-Douglas, and new tools will have to be developed beyond the scope of existing efforts, such as new financial, legal, and contractual tools for supporting utility investments. The rulemaking introduced the concept of climate adaptation planning as a prudent next step to ensure safe and reliable service from investor-owned utilities in a time of worsening climate impacts. It will focus initially on the electric and natural gas sectors, which are already taking a lead in climate vulnerability assessment and adaptation but will be expanded in the future to include water and telecommunications sectors as well, said Ralff-Douglas. The proceedings will be informed by working groups and robust stakeholder engagement to gain insight from groups that do not typically participate in the general rate setting process (e.g., climate scientists and resilience researchers).

Ralff-Douglas explained that the scope of energy sector climate adaptation is immense, spanning individual assets to interdependent infrastructure systems across multiple companies, planning and operational procedures, employees and workforce, and customer characteristics and behaviors. It is insufficient to think about the resilience of individual assets alone, and instead planning needs to be regional, sector-wide, and even across sectors, although this can present a significant institutional challenge. In the Bay Area, she explained, there are numerous utility assets as well as private company facilities, water treatment, and large transportation infrastructure (e.g., large airports and bridges), and protecting each asset individually may be more expensive and

___________________

5 State of California, Public Utilities Commission, “Order Instituting Rulemaking to Consider Strategies and Guidance for Climate Change Adaptation,” Draft, April 26, 2018, http://docs.cpuc.ca.gov/PublishedDocs/Published/G000/M213/K503/213503721.PDF.

6 State of California, “Climate Change: Infrastructure Planning,” Assembly Bill No. 2800, Chapter 580, September 24, 2016, https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160AB2800.

suboptimal compared to coordinated regional approaches. Another challenge will be to build in greater flexibility for the electricity system, because adaptation will be continual and there is no new normal, she said. Several California utilities have completed initial vulnerability assessments and are developing resilience plans through the DOE’s Partnership for Energy Sector Resilience, and Ralff-Douglas described the need to evolve the next round of assessments to consider extreme events and to test the boundaries of system performance beyond just considering average changes. Some regulatory processes may also need to be reexamined, she concluded, because long-standing processes, like the general rate cases structure, are not well suited for long-term climate resilience planning (i.e., 3-year scope, based largely on financial prudence) and even the 10-year time frame considered in the long-term procurement planning process is too short for meaningful long-term climate adaptation considerations.

SUSANNE MOSER, SUSANNE MOSER RESEARCH AND CONSULTING

Moser reflected on 20 years of experience working on climate assessments in California, noting that the process is far more challenging and messier than comes across in presentations, and she challenged participants to envision what the process may look like 20 years from now. California’s assessments have evolved over time—from focusing on climate science to focusing on impacts on humans and infrastructure, from statewide to regional emphasis, from sectoral studies to considering systemic interdependencies, and from natural science dominated to more inclusion of social sciences and interdisciplinary studies. With these positive trends, there are still opportunities to improve the assessment process—for example, through greater engagement with decision makers and research users early in project definition, scoping, and selection. Co-production of scientific knowledge occurs along a spectrum, she explained, from convening a single workshop or event to understand practitioner needs through a sustained and continual engagement that permeates the entire process from scoping a project through knowledge co-generation to implementation, and there is still a lot of room for improvement in California.

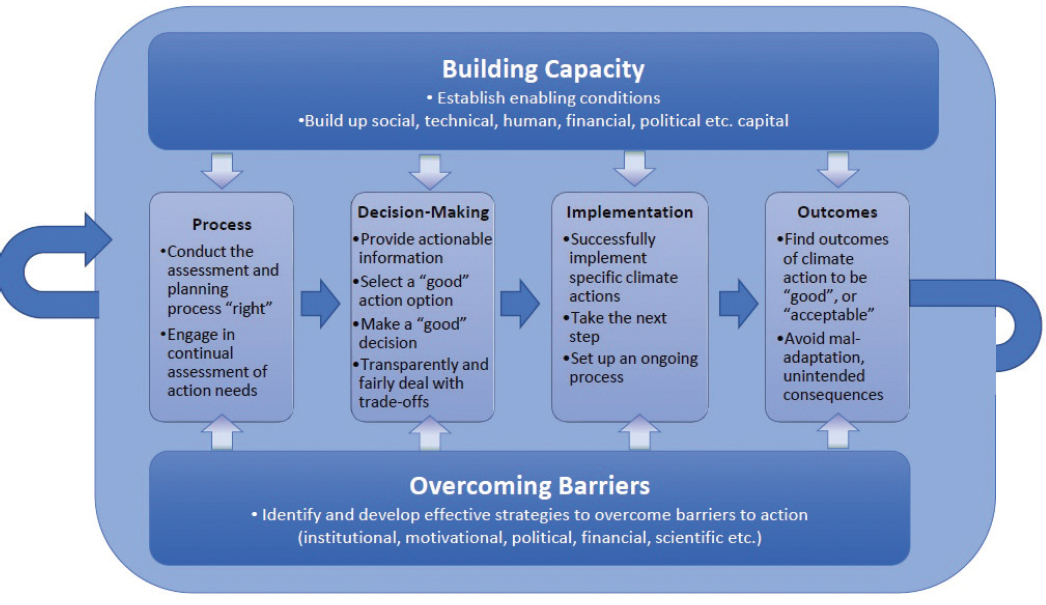

In the context of scientific assessments to guide policy and planning decisions, Moser emphasized that knowledge is always a strategic tool and that there is no scientific knowledge that is inherently valuable, certain enough, or decision-relevant. Instead, a variety of political considerations such as personal or political motivation, economic benefits or liabilities, and reputational liabilities can all drive what and how scientific information becomes relevant and is used. She appealed for more attention to be placed on the political context and decision-making process, noting that an assessment can have the best science but still result in limited benefit if the political process is flawed. The need for greater user relevance has driven a shift in California, from initially seeking better understanding of science through assessment, to striving for improved relationships between scientists and policy makers and the public, to focusing on science that could support better decision making and ultimately more desirable outcomes. The literature on useful and usable science has long established the characteristics of useful assessment information—assessment users must find the information salient, credible, and legitimate, enhancing the ease and efficacy of making decisions, and being easily updatable. Moser shared an iterative framework that emphasized six dimensions for conducting successful assessments and linking them to action (adopted from a separate project): having a process in place that is effective, inclusive, and continually improved; supporting decision making that is transparent and fair; implementing strategies and taking incremental actions; achieving desirable outcomes and avoiding negative unintended consequences; building capacity, whether human, technical, political, or other, for assessment and adaptation actions; and overcoming barriers to participating effectively in any step of this process (Figure 5.2).

Moser applied the lessons learned from 20 years of engaging at the science-practice/policy interface in her work co-facilitating the Climate Safe Infrastructure Working Group (CSIWG, 2018), chartered through Assembly Bill 2800, to provide guidance on how to integrate projected climate change impacts into engineering project decision making from planning, design through construction, operation and maintenance, and ultimately decommissioning. The group convened leading architects, engineers, climate scientists, and economists from institutions across the state with expertise across the building, energy, transportation, and water sectors. Through structured meetings, webinars, literature reviews, and outreach the working group developed a consensus report (CSIWG, 2018) that briefly reviews findings from the Fourth Assessment to frame the challenge but focuses predominantly on strategies to connect that climate science to engineering decisions. Moser explained that the type of data and analysis needed

by infrastructure practitioners—for example, vulnerability assessments and risk forecasts—are several steps removed from most climate science research, so significant translational work is required. Moreover, engineers need much more than climate science to adequately plan and ultimately decide on their infrastructure projects (land use and population forecasts, economics of alternative designs, life cycle costs of a particular project, the cost of including versus ignoring climate change considerations, etc.). The report emphasizes a systems approach to climate-safe infrastructure development, including developing a robust project pipeline with viable projects ready for investment, establishing governance structures (e.g., through engaging professional societies to develop new standards and norms) and financing tools for projects, training the future workforce and addressing other contextual conditions to ensure climate-safe infrastructure gets built. Briefly reflecting on the working group’s experience, Moser said there was a long way to go for full climate literacy in California, even among leading state engineers and officials, and that risk aversion to deviating from historical practices and norms combined with varying capacities and resources available to commit to climate adaptation would be barriers for years to come.

She closed with her vision for the state’s assessment process 20 years in the future—it could be led by the California Department of Public Health and the Legislative Analyst’s Office, with lesser roles for state agencies traditionally involved in the assessment, but local and private-sector co-leadership; it might be funded by the State Legislature, the California Chamber of Commerce, and the California Infrastructure Bank; it would be driven by user needs as opposed to scientific questions; and it will focus on accelerating large-scale implementation of solutions, addressing legal and liability issues, compensation and funding mechanisms, and complex interactions between a changing climate and implemented solutions. Most of the assessment is likely to focus on solutions and outcomes, she concluded, with only a small bit of climate science focused on tipping points and related large-scale disruptions. In short, she surmised, it will look very different than it does now.

PANEL DISCUSSION

Wall began by reflecting on a common theme across presentations of how good science can shape policy solutions and how good policy can support scientific advancements. Jennifer Jurado asked how positive relationships between academic institutions and state organizations were fostered in California, and how they could be replicated elsewhere. Moser responded that the state’s commitment and consistent funding for climate research awarded through open competitions has created a strong network of collaborators in the state. While this network is growing with the Fourth Assessment to include more diverse participants, there remain opportunities to improve, particularly with respect to inclusion of social sciences, she said.

Craig Zamuda, DOE, commented that it was encouraging to hear about great efforts outside the federal government, and California appears to be leading the way in climate adaptation. Zamuda appreciated references to the DOE partnership and is producing two documents soon, including a cost and benefit guide for climate resilience investments as well as defining characteristics of a resilient utility. Wall concluded by asking the panelists if there were any topics that were clearly ready for action without further research or if they had specific research needs that could inform their actions. Ralff-Douglas responded that she and utility commissions more broadly would like to be able to assign exceedance probabilities for numerous environmental variables (e.g., SLR, maximum temperature) at locations across the state.

PAUL A. DECOTIS, WEST MONROE PARTNERS

Paul DeCotis, chair of the workshop planning committee, reflected on presentations from the first day and commented that the deep history in climate science, informed state policy, and local action evident in California took decades to develop, and he thanked California for “being the de facto leader in climate change research, assessments, and academic studies in the country if not the world.” He described several highlights and themes from the preceding panels, including the following:

- The devastating fires of 2017 and 2018, their impact on public health and public perception of climate change, and their impact on watershed and ecosystem health;

- The need for probabilistic risk management in decision making (e.g., by utilities and their regulators) and the value of developing and presenting scientific information in ways that support decision making despite uncertainty;

- The need to engage diverse sectors and stakeholders in developing and implementing adaptation strategies, as well as the opportunity to improve engagement with the private sector;

- The value of developing decision support tools based on available science, because current knowledge is sufficient to allow informed risk-based decisions by utilities and other organizations.

He briefly explained that the goals for the second day of the workshop were to explore commonalities and differences between other subnational assessments and California’s Fourth Assessment. The panels and breakout were designed to emphasize the assessment process and how it may evolve to be more impactful, become more pervasive, and be sustained.

DeCotis closed by commenting that, although climate change is a global phenomenon, its impacts are local and that is where policy decisions are made. While California continues to produce excellent climate research and informed policy, climate change and its impacts will not stop. He commented that too much of the public narrative surrounding climate change focuses on the causes, mechanisms, and impacts of a changing climate, ignoring that the climate has already changed and that the future trajectory could bring severe consequences. It should matter less who is responsible for the changed climate, said DeCotis, but rather how communities will adapt, who is going to do it, and how it will be paid for. Protecting natural and physical assets, public health, and cultures through climate change is an enormous proposition, and local, state, and federal elected officials need to be informed of the potential impacts to their local communities and constituents. Reflecting on his experience in the financial sector, he described the importance of defining the benefits of acting (economic and broader), the potential avoided

costs of excess storms and fires, and additional opportunities for deriving value in new investments in a changing environment. We know enough already to push forward, DeCotis concluded, encouraging a coordinated call to action for policy makers and the private sector.

REFERENCES

CSIWG (Climate Safe Infrastructure Working Group). 2018. Paying It Forward: The Path Toward Climate-Safe Infrastructure in California. Report of the Climate-Safe Infrastructure Working Group to the California State Legislature and the Strategic Growth Council. Sacramento, Calif. CNRA-CCA4-CSI-001. http://resources.ca.gov/climate/climate-safe-infrastructure-working-group/.

Griggs, G., J. Árvai, D. Cayan, R. DeConto, J. Fox, H.A. Fricker, R.E. Kopp, et al. 2017. “Rising Seas in California: An Update on Sea-Level Rise Science.” California Ocean Science Trust. http://www.opc.ca.gov/webmaster/ftp/pdf/docs/rising-seas-in-california-an-update-on-sea-level-rise-science.pdf.

Pierce, D.W., J.F. Kalansky, and D.R. Cayan. 2018. “Climate, drought, and sea level rise scenarios for California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment.” California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment. CNRA-CEC-2018-006. http://www.climateassessment.ca.gov/techreports/docs/20180827-Projections_CCCA4-CEC-2018-006.pdf.

State of California. 2018a. California Coastal Commission Sea Level Rise Policy Guidance: Interpretive Guidelines for Addressing Sea Level Rise in Local Coastal Programs and Coastal Development Permits. Draft Science Update. October. https://documents.coastal.ca.gov/assets/climate/SeaLevelRisePolicyGuidance_Update_Oct.MARKUPClean.pdf.

State of California. 2018b. California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment. http://www.climateassessment.ca.gov/.

Thomas, N., M. Shruti, B. Galey, and M. Kelly. 2018. “Cal-Adapt: Linking Climate Science with Energy Sector Resilience and Practitioner Need.” California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment. CCCA4-CEC-2018-015. http://www.climateassessment.ca.gov/techreports/docs/20180827-Projections_CCCA4-CEC-2018-015.pdf.