6

Finding Commonalities and Differences with Other Subnational Assessments (Part 1)

The first session on day two explored subnational climate assessment activities outside California and across the United States to share examples and learning from other states, regions, and sectors. Although the climate vulnerabilities and assessment process challenges differ across regions and sectors of the U.S. economy, the session focused on commonalities, including the process of implementing a climate assessment; the methods and issues in engaging key stakeholders; and the need for translating this information into actions. The discussion included what the key elements are of regional, state, local, and sector-specific climate assessments; how those elements are determined; and how the assessment engages and leverages local and national resources. Jennifer Jurado (Broward County government in Florida) moderated the session, calling attention to the diversity of regions and actors reflected across the upcoming presentations. Cathy Whitlock (Montana State University) described her effort coordinating the Montana Climate Assessment, which had a rural and resource focus that contrasts with many of California’s more urban areas. Donald Wilhite (University of Nebraska) explained the sectoral approach taken in an assessment of Nebraska’s climate change vulnerabilities and expanded on the challenges of conducting and implementing assessments absent local political engagement. Amanda Stevens (New York State Energy Research and Development Authority) shared the process and findings of the state’s 2011 climate vulnerability and adaptation assessment and described current thinking regarding the next planned iteration. Jeffrey Dukes (Purdue University, Indiana) shared their bottom-up assessment efforts led by a center at the university and described how the process will facilitate dialogue around climate change, beyond simply providing project impacts. Zena Grecni (East West Center in Hawaii) described the Pacific Island Regional Climate Assessment, emphasizing the importance of forming partnerships with local academic institutions.

MODERATOR: JENNIFER JURADO, BROWARD COUNTY, FLORIDA

Jurado introduced the session by noting how the second day’s sessions would build on the impressive work in climate assessment going on in California by considering the quality and diversity of work going on across the country. She noted how this first session will feature a transect of examples of state climate assessments and then introduced the panelists from Montana, Nebraska, New York, Indiana, and Hawaii.

CATHY WHITLOCK, MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY

Whitlock began by describing the Montana Climate Assessment (MCA),1 which was released in September 2017 (Whitlock et al., 2017). She characterized the assessment as a grand experiment for a small-population, conservative state like Montana. The first part of the experiment was that it was a large partnership that included both major universities in Montana, several departments within Montana state government, federal entities, and the tribal colleges. One motivation for undertaking the assessment is the “right to a clean and healthful environment” that is included in the Montana State Constitution. Another key motivation was to understand the potential impacts of climate change on three components of Montana’s economy: the fast-growing “micropolitan” and amenity sector based on recreation and wildlands; the resource-dependent agricultural, timber, and energy sectors vulnerable to issues such as commodity prices and regulatory decisions; and rural communities where persistent poverty, isolation, and historical factors will determine the intensity of climate impacts. The assessment was stakeholder-driven and science-informed, and it included listening sessions and questionnaires to gather stakeholders’ input in shaping the assessment. Its scientific base built on the efforts of the U.S. Global Change Research Program and drew on the capabilities of the state universities.

The central goals of the assessment were to explain how Montana’s climate will change in the 21st century and to discuss potential impacts for three key sectors: water, forests, and agriculture. Whitlock said that the future climate analysis used downscaled estimates from 20 general circulation models that were then upscaled to the seven National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration climate regions in Montana. The assessment also developed monthly and seasonal temperature and precipitation estimates for the different regions. The models were in agreement on the magnitude of statewide increases in summer and winter temperature in the future. Precipitation, which is also a big concern for Montana, showed greater intermodel variability in the results, with most showing slight increases in overall precipitation in the future, and with more occurring in winter, spring, and fall with less in the summer.

The assessment started with a presentation of historical climate trends in Montana. This included the observation that average temperatures across the state have risen 2-3°F over the period of 1950-2015, with most warming in winter and spring. This finding matches most Montanans’ observations and experiences and has provided a common reference point for initiating discussion. The assessment next discusses future climate projections for the state, highlighting estimates of increased warming, additional extreme heat days, and changes in the seasonal patterns of precipitation. The consequences of these changes for water resources focus on an analysis of seven major watersheds in Montana that will likely experience decline in snowpack, earlier spring runoff, and greater frequency and severity of late-summer droughts. In discussing the impacts to forest ecosystems, the assessment covers direct and indirect effects such as decreased growth in dry forests as well as increased forest fires and insect outbreaks. The chapter on agriculture explains some potential impacts of climate change on crops and livestock, including on nonirrigated wheat, which is the primary product in Montana. In particular, Montana is well known for its spring wheat, and farmers are concerned that summers will become too hot for its production. In response, efforts are under way to identify new varieties of wheat that are more heat tolerant, new treatments for weeds, and alternative crops. Whitlock noted that farmers and ranchers face complex decisions and numerous trade-offs in managing their operations. Furthermore, every component of agriculture—from commodity prices to plant pollinators and pests—is influenced by climate and weather variability as well as agricultural and economic practices and policies.

The findings of the assessment are currently being shared around the state, with Whitlock and co-authors speaking at rallies, roundtable events, community meetings, and a variety of other venues. A major drought and associated wildfires in 2017 have helped focus public attention on the assessment. Whitlock said talking about climate change in the context of the drought has helped build credibility for the assessment in communities that might otherwise have been skeptical. The concerns raised at public events have been broad in scope and include issues related to water availability and storage capacity in the future, floods and droughts, wildfire response and planning, livestock and crop decisions, and economic and human-health considerations. Whitlock also noted that

___________________

1 Montanta Institute on Ecosystems, “Montana Climate Assessment,” http://montanaioe.org/mca.

the groups involved in the MCA are in the process of developing a boundary organization, the Montana Adaptation Knowledge Exchange, designed to build the linkages from science to action and to identify stakeholder needs that can further guide scientific research. The priority for this organization is on climate adaptation and building on the findings of the climate assessment, she concluded.

DONALD WILHITE, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA

Wilhite began his remarks by discussing the climate assessment done by the University of Nebraska (Bathke et al., 2014), noting that a lot of the projections and outcomes discussed in relation to the Montana climate assessment were similar to the ones that are found in Nebraska. Wilhite explained that this was a university-sponsored report in response to legislation passed in 2013. The university study was more comprehensive than the one called for in legislation, and the assessment featured an interdisciplinary team from the university focusing on climate change science, observed and projected changes, and potential impacts to key sectors. This was a science-based assessment and not policy oriented, he said, and the report was released through a public forum to state-wide media coverage. The follow-up to this report included a series of eight sector-based roundtable discussions that engaged stakeholders and the interested public around specific themes including public health; urban and rural communities; agriculture, food and water; climate change and the faith community; wildlife, ecosystems, and ecosystem services; and forests and fire. The roundtables had more than 350 participants combined, with a report on the roundtables available on the study website.2

Wilhite went on to describe the outcomes and next steps for climate assessment and adaptation in Nebraska. He said that the report served as a catalyst for many nongovernmental organizations, and a follow-up poll of rural Nebraskans conducted by the university showed that 61 percent of respondents support development of a climate action plan, which Wilhite noted showed a high level of concern about this issue among the most conservative residents in the state. The activity led to a series of youth summits on climate change organized by state senators and held in the state capital, as well as to the formation of the Nebraska Elder Climate Legacy Initiative.3 Wilhite concluded with observations on the challenges and best practices learned from the Nebraska assessment, such as the challenge of establishing and maintaining political momentum and support from the agriculture community and Nebraska’s Natural Resource Districts. The best practices he identified included performing a science-based assessment with content developed and focused on a specific audience; having active stakeholder engagement and additional educational outreach efforts; and engaging and educating state senators and other policy makers.

AMANDA STEVENS, NEW YORK STATE ENERGY RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY

Stevens began her talk by describing the mission of her employer, the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), as advancing innovative energy solutions in ways that improve New York’s economy and environment. The Environmental Research Program at NYSERDA looks at the impacts of energy generation and use, including climate change impacts and adaptation research. The ClimAID Assessment, Responding to Climate Change in New York State,4 came out of this program in 2011 (Rosenzweig et al., 2011a,b) and the projections were subsequently updated in 2014 (Horton et al., 2014). The lead researchers were from Columbia University, Cornell University, and the City University of New York, with the larger team including dozens of additional researchers.

The assessment itself was divided into three main topic areas: climate risks, impacts and vulnerability, and adaptation. The first part of the assessment was to develop projections of changes in temperature, precipitation, and other climatological parameters for seven regions in the state. Although many of the parameters did not vary

___________________

2 University of Nebraska, Lincoln, “Climate Change Implications for Nebraska,” http://go.unl.edu/climatechange.

3 See the Nebraska Elder Climate Legacy Initiative website at https://www.elderclimatelegacy.org/.

4 New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, “Responding to Climate Change in New York State (ClimAID),” http://www.nyserda.ny.gov/climaid.

significantly from region to region, Stevens said that providing such regional detail helped bring the issue home to people through imagining the consequences of such changes in the places where they live. Impacts and vulnerabilities related to these projections were then assessed for eight sectors: agriculture, coastal zones, ecosystems, energy, public health, telecommunications, transportation, and water resources. Potential adaptation strategies were also discussed for the vulnerabilities identified in each sector. Stevens noted that the assessment team ensured that the three themes of climate risk, vulnerability, and adaptation were integrated well and discussed consistently across all of the sectors. Last, Stevens said that crosscutting elements of environmental justice and equity, economic analysis, and science-policy linkages were also incorporated into each of the sector reports. Numerous stakeholders from every sector were involved throughout the assessment process, she explained, to better understand how the projected climate changes might impact their sector. The products of this assessment included not only the main report but also a short summary document and an appendix to the report, as well as an adaptation guidebook that attempted to walk readers through completing a vulnerability and adaptation assessment. The sea level rise (SLR) projections developed through ClimAID are now used as the official New York State SLR projections, as well as by counties and other municipalities in comprehensive hazard mitigation planning. Reflecting on successful practices, Stevens opined that they had a great team of experts that had the time needed to produce a comprehensive assessment. Going forward, she described opportunities to improve stakeholders’ engagement to better understand the “usability” of different information outputs and what type of information was needed to make decisions. They also could have done more outreach, including dissemination activities around the state, as was discussed with the Montana Climate Assessment.

Stevens concluded with thoughts on future New York State assessments, noting that the ClimAID assessment was groundbreaking in the state for its time, but that the science and decision-making needs have evolved since 2011. Any future state assessment will continue to be grounded in the science—that is the foundation of the Environmental Research Program at NYSERDA, but efforts will need to be more usable for stakeholders and provide them the information they need to make good decisions.

JEFFREY DUKES, PURDUE UNIVERSITY CLIMATE CHANGE RESEARCH CENTER

Dukes opened his presentation by giving an overview of his work on the Indiana Climate Change Impacts Assessment5 from his position as the director of the Purdue Climate Change Research Center, an interdisciplinary center that provides nonpartisan information and collaborative opportunities on issues related to climate change. He described the context for climate assessment in Indiana, noting that the state has high per-capita energy use, and not only is there no state-level climate policy, but the state is actively working against federal climate regulations. Furthermore, climate change is rarely discussed by its residents and a minority of residents agree with the statement: “Most scientists think global warming is happening.”6 Dukes described the origin of Indiana’s assessment, saying that when former Senator Richard Lugar had to vote on a cap-and-trade bill in 2007, the senator realized that he had no good information about climate impacts in Indiana on which to base his vote. Lugar asked Dukes’s center at Purdue University to develop a report in approximately 20 days. The final report they developed and released in 2008 was used by many groups and was in desperate need of updating.

Dukes described their update to this report (Widhalm et al., 2018) as a bottom-up effort with no mandate or direct funding from the state. The technical contributors are about 100 volunteers from universities and other groups with technical expertise around the state. The assessment produced paired technical and public reports based on scientific articles intended for publication in special issues of the journal Climatic Change. These are then used by the center staff to develop public-facing reports that are as accessible as possible to the stakeholders and public at large.7 The assessment is intended to answer the question: “What does climate change mean for Indiana?” He explained that the effort does not make mitigation and adaptation recommenda-

___________________

5 Purdue University, “Indiana Climate Change Impacts Assessment,” https://ag.purdue.edu/indianaclimate/.

6 J. Marlon, P. Howe, M. Mildenberger, A. Leiserowitz, and X. Wang, “Yale Climate Opinion Maps 2018,” August 7, 2018, http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/ycom-us-2018/?est=happening&type=value&geo=county.

7 Most of these topical reports are currently available at http://IndianaClimate.org.

tions, but rather provides an assessment of climate change impacts on different sectors. Dukes said the main goal is to provide usable information to stakeholders, but in doing so the researchers are actively working to increase climate change dialogue in the state and to build a network of experts and stakeholders that can provide information and solutions for climate change in the future.

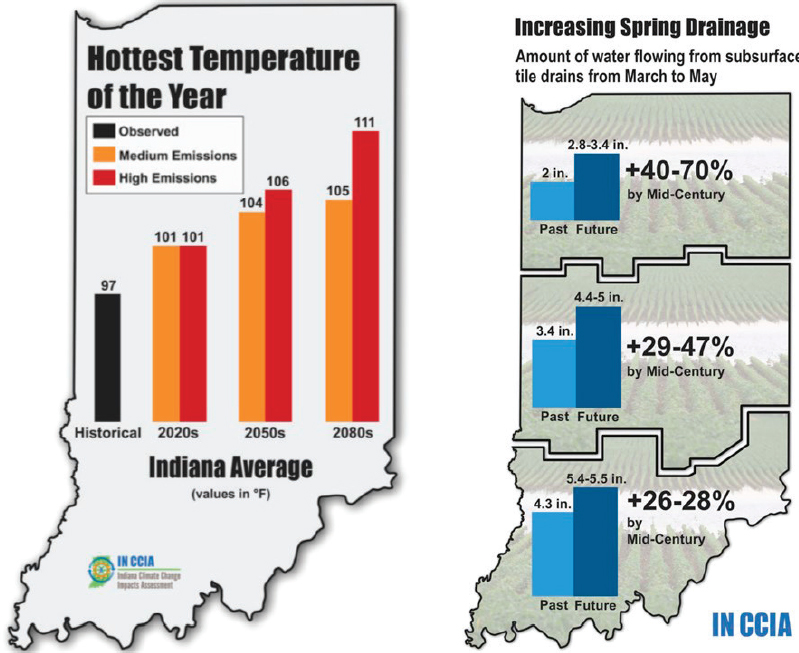

Dukes said the process for developing this assessment began with stakeholder engagement, which they used to inform the creation of working groups that matched stakeholder interests with available expertise. They use a wide variety of mechanisms to connect with stakeholders, including community events, social media, monthly online newsletters, and a public-facing website. The working groups also developed a technical report with content based on stakeholder input, existing research, and capacity to conduct new research, which center staff then translated into nontechnical summaries for the public. These are being released on a rolling schedule beginning in March 2018, and the first of these reports cover topics including climate, health, forest ecosystems, urban green infrastructure, agriculture, and aquatic ecosystems. The public reports are intended to provide easily accessible information with numerous engaging graphics (Figure 6.1) and minimum technical details, and with limited reference to the technical reports that provide the scientific foundation. Dukes explained that researchers are spreading the word on the assessment by releasing these public reports individually at community briefings at different locations around the state. By spacing out the report releases and getting local media coverage in different markets for each event, Dukes hopes to raise coverage and engagement with the Indiana assessment. Dukes concluded by questioning how to measure the impact of a local climate assessment. He noted that a number of local newspapers are producing front-page stories on the assessment reports, and said he looked forward to discussions on how to measure success.

ZENA GRECNI, EAST-WEST CENTER

Grecni introduced herself as the sustained climate assessment specialist for Hawaii and the U.S.-affiliated Pacific Islands, which allows her to focus exclusively on regional climate assessments and how to link these to the national assessment of the USGCRP. She shared her work with the Pacific Island Regional Climate Assessment (PIRCA),8 noting that, as with the previous discussion on Indiana, there is no top-down mandate or funding from the state of Hawaii to produce such an assessment. This underscores the importance of clear communication and building a strong network of practitioners and decision makers to drive the assessment. Grecni showed a map of the PIRCA region to emphasize its size, commenting that instead of this area being considered small island states, the U.S.-exclusive economic zones mean that they are in reality large ocean states. The region also includes large marine national monuments that contribute significantly to the biodiversity of the Pacific Ocean, as well as major U.S. military installations vital to national security. Grecni explained that the region encompasses more than 2,000 islands with a population of 1.9 million residents and with varied governance systems, incomes, geographies, cultures, and languages.

Like other state assessments, Grecni said that conducting a coordinated climate assessment in such a diverse setting depends on strong partnerships with academic institutions, local and state governments, and federal organizations. PIRCA is a collaborative effort, bringing together research on climate change and its associated risks. PIRCA products include Climate Change and Pacific Islands: Indicators and Impacts (Keener et al., 2012) and chapter on the Hawaii and Pacific Islands within the 3rd National Climate Assessment (Leong et al., 2014). The 2012 PIRCA report had a high degree of perceived credibility by its users, and the authors felt that the next assessment could improve by doing more to include a regional perspective rather than focusing mainly on Hawaii, as well as having a broader set of sectors represented.

When Grecni began her efforts as the climate assessment specialist in 2016, she started by creating a website and developing products and content better suited for digital dissemination and engagement based on earlier assessments. She and her colleagues began work for an updated chapter on Hawaii and the Pacific Islands for the upcoming Fourth National Climate Assessment (NCA). Grecni explained that this reinvigorated the PIRCA network and prompted them to undertake surveys, webinars, sectoral workshops, and town halls. Based on a survey and available published literature, the authors decided to focus the chapter for the Fourth NCA on ocean and marine resources; ecosystems, ecosystem services, and biodiversity; coastal effects; indigenous communities; freshwater resources; and cumulative impacts and adaptation. Grecni noted that PIRCA products have been used in a variety of settings including vulnerability assessments for individual islands, United Nations climate negotiations, and in speeches by numerous politicians including U.S. Senator Brian Schatz of Hawaii. Grecni concluded by looking to the future, commenting that PIRCA may have more resilience and impact due to its collaborative and locally directed leadership, and she looked forward to the opportunity to help grow a national network of sustained assessment specialists.

PANEL DISCUSSION

Jennifer Jurado, Broward County government in Florida, began the discussion with observations from the panelists’ presentations and invited the panelists to share their observations on the similarities and differences across the regional efforts presented. She noted that each panelist had expressed an appreciation for the capacity of academic institutions and researchers to bring expertise and resources to communities where climate leadership is lacking. The significance of stakeholder engagement was also highlighted across presentations, she noted. While the panelists spoke of distinctions in terms of scales of analysis, they each articulated a need to delve deeper into specific sectors and to personalize impacts and response strategies for specific audiences. Jurado noted some reluctance to provide policy recommendations aiding state or local governments with response strategies, but reiterated comments on a prioritization of action strategies in forthcoming efforts. Amanda Stevens, New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, underscored Grecni’s comments on the value of creating a

___________________

8 Pacific Regional Integrated Sciences and Assessments, “Pacific Islands Regional Climate Assessment,” https://www.pacificrisa.org/pirca-website/.

network of sustained assessment experts to share knowledge. Cathy Whitlock observed that many panelists noted the struggle to keep the assessment process sustained as new scientific information is produced and decision maker needs evolve.

Susan Julius from the Environmental Protection Agency spoke of building adaptation into the vulnerability impact assessment process in response to demand from communities. She asked the panel to elaborate on their experience with incorporating adaptation into assessment activities. Wilhite responded that while organizing the research of University of Nebraska’s report, they led with impacts to grab audience attention. This paved the way to discuss projections and adaptation strategies, but he agreed that adaptation and mitigation can be more difficult to broach with audiences. Grecni added that in the Pacific Islands, adaptation activities are more prevalent, and her organization tries to meet stakeholders where they are in the process, whether that requires augmenting data on impacts or working on adaptation strategies.

Bruce Riordan asked the panel about lessons learned regarding university cooperation in assessment activities. Dukes responded that at Purdue University, they attempt to make it worth the academic volunteers’ time (e.g., through journal publications). Whitlock discussed the importance at Montana State University of making the heavily technical information from faculty contributors more comprehensible to the public. Stevens added that highlighting university participation was a technique NYSERDA used when disseminating its assessment, as it received a different reception than a research product coming from the state. Wilhite related that, while University of Nebraska was supportive of their most recent project, past efforts to begin a university climate initiative were unsuccessful, highlighting the importance of timing and faculty priorities.

Virginia Burkett, U.S. Geological Survey, reiterated the importance of subnational assessments to inspire states to take action, as they are able to gather more regionally specific information than the national efforts. Jonathan Parfrey expressed support for a network of assessment practitioners and noted that in California, scientific data have been popularized but actual experienced events such as wildfires and heat waves have been far more persuasive to the public and to policy makers. He asked panelists if there is a perception among other states that California has a competitive advantage because they are actively preparing for climate change, while states that are not could be left behind. Jeffrey Dukes responded that an effective way of reaching people is to engage as many stakeholders as possible before the assessment process has begun. In regard to changing people’s perceptions with scientific data, Dukes explained that it may not be possible, but launching a conversation is a desired outcome. Because Indiana is not facing some of the same urgent, tangible threats that California is, Dukes said that there is not a pervasive competitive attitude with California. Amanda Stevens added that case studies from neighboring communities were also found to be very persuasive.

REFERENCES

Bathke, D.J., R.J. Oglesby, C.M. Rowe, and D.A. Wilhite. 2014. “Understanding and Assessing Climate Change: Implications for Nebraska.” University of Nebraska, Lincoln. http://snr.unl.edu/download/research/projects/climateimpacts/2014ClimateChange.pdfb.

Bowling, L., M. Widhalm, K. Cherkauer, J. Beckerman, S. Brouder, J. Buzan, O. Doering, et al. 2018. “Indiana’s Agriculture in a Changing Climate: A Report from the Indiana Climate Change Impacts Assessment.” Purdue Climate Change Research Center. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=agriculturetr. DOI: 10.5703/1288284316778 https://ag.purdue.edu/indianaclimate/agriculture-report/

Horton, R.D., D. Bader, C. Rosenzweig, A. DeGaetano, and W. Solecki. 2014. “Climate Change in New York State: Updating the 2011 ClimAID Climate Risk Information.” New York State Energy Research and Development Authority. http://www.nyserda.ny.gov/climaid.

Keener, V.W., J.J. Marra, M.L. Finucane, D. Spooner, and M.H. Smith, eds. 2012. “Climate Change and Pacific Islands: Indicators and Impacts.” Report for the 2012 Pacific Islands Regional Climate Assessment. https://www.cakex.org/sites/default/files/documents/NCA-PIRCA-FINAL-int-print-1.13-web.form_.pdf.

Leong, J.A., J.J. Marra, M.L. Finucane, T. Giambelluca, M. Merrifield, S.E. Miller, J. Polovina, et al. 2014. Hawai‘i and U.S. Affiliated Pacific Islands.” Chapter 23, pp. 537-556 in Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment (J.M. Melillo, T.C. Richmond, and G.W. Yohe, eds.). U.S. Global Change Research Program. doi:10.7930/J0W66HPM.

Rosenzweig, C., W. Solecki, A. DeGaetano, M. O’Grady, S. Hassol, and P. Grabjorn, eds. 2011a. Responding to Climate Change in New York State: The ClimAID Integrated Assessment for Effective Climate Change Adaptation: Synthesis Report. New York State Energy Research and Development Authority. http://www.nyserda.ny.gov/climaid.

Rosenzweig, C., W. Solecki, A. DeGaetano, M. O’Grady, S. Hassol, and P. Grabjorn, eds. 2011b. Responding to Climate Change in New York State: The ClimAID Integrated Assessment for Effective Climate Change Adaptation: Technical Report. New York State Energy Research and Development Authority. http://www.nyserda.ny.gov/climaid.

Whitlock, C., W. Cross, B. Maxwell, N. Silverman, and A.A. Wade. 2017. “Montana Climate Assessment.” Montana State University and University of Montana, Montana Institute on Ecosystems. http://live-mca-site.pantheonsite.io/sites/default/files/thumbnails/image/2017-Montana-Climate-Assessment-lr.pdf.

Widhalm, M., A. Hamlet, K. Byun, S. Robeson, M. Baldwin, P. Staten, C. Chiu. et al. 2018. “Indiana’s Past and Future Climate: A Report from the Indiana Climate Change Impacts Assessment.” Purdue Climate Change Research Center. doi: 10.5703/1288284316634. https://ag.purdue.edu/indianaclimate/indiana-climate-report/.