9

Initiating, Sustaining, and Evolving Climate Assessment Processes

The final session of the workshop focused on innovations to climate assessment processes, focusing specifically on strategies for initiating, sustaining, and evolving these processes. As illustrated in the presentations over the 2 days, climate assessments are iterative, and change based on decision and policy maker needs as well as improved scientific understanding. Panelists described challenges in securing funding and stakeholder interest to initiate assessment and looked ahead to how assessment content and process could change going forward. Paul DeCotis (West Monroe Partners) moderated the discussion, emphasizing the importance of building trust between analysts and policy makers. Delavane Diaz (Electric Power Research Institute) described how climate assessments are moving into the utility sector and shared modeling results, calling attention to the importance of incorporating larger systemic changes into climate assessment models. Jennifer Jurado (Broward County government in Florida) elaborated on challenges financing large-scale adaptation efforts and articulated the importance of communicating effectively to the public about local bond initiatives and other financing strategies. David Reidmiller (U.S. Global Research Change Program [USGRCP]) described the Fourth National Climate Assessment and its regional chapters as an important evolution in their approach to national assessments. Richard Moss (Columbia University) shared his work on sustaining national climate assessment efforts in a time of diminished federal support. Louise Bedsworth (California Strategic Growth Council) expanded on dissemination plans for California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment (State of California, 2018) and provided comments on how the state’s assessment efforts may change in the future.

MODERATOR: PAUL A. DECOTIS, WEST MONROE PARTNERS

DeCotis began the session by underscoring the importance of building trust between technical analysts and decision makers to make the findings of climate assessments more actionable. He suggested assessments build support from several smaller sources of funding rather than from a few larger sources as a strategy to sustain funding. DeCotis introduced the speakers on the panel, noting that they represented industry, academic, local, and federal government perspectives on the future of climate assessment processes.

DELAVANE DIAZ, ELECTRIC POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE

Diaz described research under way in the Energy and Environmental Analysis group at the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) to advance climate resiliency and risk management strategies, including model-

ing efforts to support planning and operations in the electric sector. She highlighted three considerations that are relevant for electric system planning for climate change: different drivers and motivations across electric companies but a common need for integrated resource planning; climate as one of several factors alongside socioeconomic and technological change shaping the future electric sector; and the importance of accounting for climate extremes and variability, not just incremental change, in risk analysis. Diaz underscored the potential for important dynamics to be missed by imposing a future climate on current conditions, rather than on projected future conditions that incorporate the other nonclimatic factors, and described EPRI’s modeling of end-use demands based on both climate change and underlying trends. For example, warming from climate change is understood to increase electricity demand for summer cooling while reducing winter heating demand, yet there are countervailing factors related to improvements in cooling technology and building shell efficiency as well as increased adoption of electric air-source heat pumps due to their increased cost-effectiveness relative to furnace heating. Accounting for these trends, alongside others including deployment of electric vehicles, suggests that even in the context of climate change, winter peak demand will exceed summer peak demand in many regions of the United States, she said, noting that capital investment decisions will be made based on a system’s peak load. Within the electric sector, the trend toward efficiency and electrification has a co-benefit of making the system more resilient to future climate change, by dampening the summer peak. EPRI’s ability to look synchronously at supply and demand changes through integrated modeling is key to understanding and informing planning needs in an evolving future electric system.

JENNIFER JURADO, BROWARD COUNTY, FLORIDA

Jennifer Jurado described the experience of Broward County, Florida, in organizing resilient investments, especially in transitioning from framing investment around climate impacts to framing investment around economic resilience. Broward County is a region where climate change is in active conversation and a mainstream concern, she said. The economic consequences of climate change are being realized today, particularly in insurance, bond ratings, and real estate values. Extreme events, especially increasing flooding conditions, are obvious. The county proposed an increase in sales tax to fund transit and infrastructure, including that needed to respond to climate change impacts, but the measure failed in 2016, in large part due to lack of private sector and media support. She explained that this led to a rethinking of how to communicate about climate change at the county level, including broader, more active engagement with the community. Simultaneously, building off a decade of regional engagement on climate change impacts, partner counties in the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Compact began to facilitate conversations between the public and private sectors, particularly involving economic sectors likely to be impacted by climate change, such as the insurance and building industries. Meetings and workshops over the course of a year led to development of economic resilience as a key focus in the region’s climate action plan and a statement of public-private sector collaboration on economic resilience that has received broad endorsement. Jurado described how the media joined in the conversation, including participating in the workshops, which helped communicate with the public. The major media produced a solutions-oriented reporting campaign on climate, infrastructure, and sea level rise. Even with these conversations, the business community and media still did not think enough action was taking place, she said. In 2018, Broward County organized a climate resilience roundtable involving the business community and elected officials. Commitments from this meeting included an agreement to apply the future flood conditions map to regional risk assessment; identify priority capital improvements; develop a coordinated resilient infrastructure investment plan; and measure costs and benefits and reduction in risk. In concluding, Jurado shared four key lessons learned from the evolving discussion on resilient investments in Broward County, as follows:

- Resilient infrastructure planning and investment must be regionally coordinated and prioritized within that state and cannot be pursued as stand-alone projects.

- Plans must deliver return on investment at local and county-wide levels to gain community-wide support.

- Private sector and media support will be vital, as seen in historical regional economic initiatives.

- Trust is not sufficient, and gaining support will require detailed plans, intermediate timelines, and inclusion of economics.

DAVID REIDMILLER, U.S. GLOBAL CHANGE RESEARCH PROGRAM

Reidmiller walked the audience through the history of the National Climate Assessment (NCA), which provides a mechanism to synthesize authoritative climate information at a national level. A quadrennial assessment of the physical science of climate and the impacts by sector are mandated by law. He described how the assessments have been authored by teams of federal and nonfederal experts, often supervised by a federal advisory committee or other steering groups. A common theme across all four NCAs was extensive stakeholder engagement to identify salient issues and information needs. Reidmiller shared how the NCA format has changed across iterations, reflecting the evolving needs of federal and nonfederal stakeholders. The most recent report, NCA4 Volume I (Climate Science Special Report; USGCRP, 2017) published in November 2017, highlights advances in the physical science of detection and attribution, leading into discussion of extreme events, and greater use of downscaled information. Another important contribution of the Fourth Assessment is a chapter on Earth system thresholds that, if crossed, could severely amplify existing risks. Volume II of NCA4 (Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States) uses the foundational physical science as presented in NCA4 Volume I to inform an assessment of the risks that climate change poses to U.S. society. He explained how NCA4 Volume II (USGCRP, 2018) has an emphasis on regional chapters. Impacts to U.S. supply chains, national security, and humanitarian goals due to international aspects of climate change are included for the first time in this newest climate assessment. Economic impacts of climate change and risk framing are topics that pervade the report. Reidmiller pointed out that mitigation and adaptation actions are also discussed in NCA4 and catalogued in databases1 used extensively by the report’s authors. Last, Reidmiller described how the federal government is addressing a sustained national climate assessment process, as well as the ecosystem of assessments that support it. The NCA is informed by the ever-growing landscape of subnational information, including state and regional assessments as well as state climate summaries.2 Reidmiller concluded by discussing how a Sustained Assessment Working Group convened under the auspices of the USGCRP is convening interagency discussions to formulate recommendations about a sustained assessment process that considers elements such as (1) indicators, data tools, and scenario products; (2) user and contributor engagement; (3) evaluation; and (4) closing the research-assessment loop.

RICHARD MOSS, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

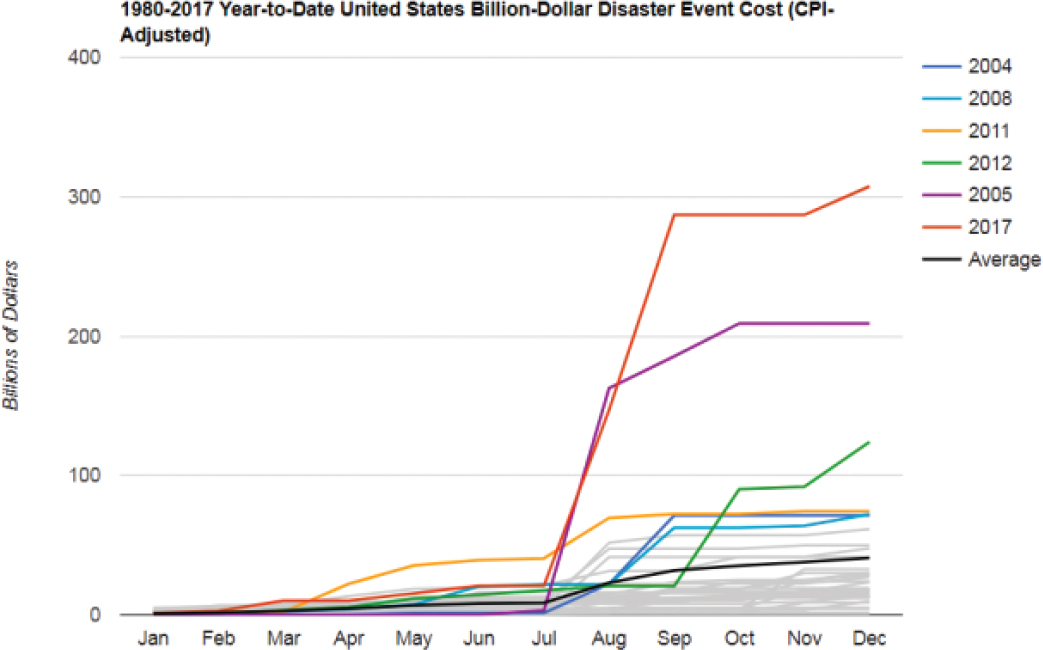

Richard Moss shared a perspective centered on his leadership of a National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration Federal Advisory Committee on Applied Climate Assessment. Although it was discontinued in August 2017 as a Federal Advisory Committee, the committee was reconstituted by many of its original members as an independent advisory committee.3 The group was composed of end users and beneficiaries of assessments such as state and local government officials, people from boundary-spanning organizations, and physical and social scientists with experience conducting climate assessments. Moss explained that the yearly cost of billion-dollar disaster events over time has increased, and recently has surpassed $100 billion in some years, even reaching $307 billion dollars in 2017 (Figure 9.1). Moss emphasized that the most effective way to limit climate risks was to reduce concentrations of greenhouse gases. Similar to the points raised by Diaz, Moss asked if funds expended on mitigation and adaptation are adequately addressing the nonstationarity of systems impacted by climate change. The last 30 years may not be a good basis for planning for the next 30 years, he said.

___________________

1 See, for example, the Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency website at http://www.dsireusa.org/ and the Georgetown Climate Center website at https://www.georgetownclimate.org/.

2 NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, “State Climate Summaries,” updated January 10, 2017, https://statesummaries.ncics.org/.

3ClimateAssessment.org, “Independent Advisory Committee on Applied Climate,” https://www.climateassessment.org/scientific-advisory-committee.

Moss shared the committee’s experience meeting with communities, saying discussions revealed that the number of problems communities face associated with climate change are not infinite, and represent a limited set of problems that are identifiable and addressable. Some of these specific problems included building weather-ready infrastructure (e.g., transportation and housing), managing development for future wildfire risk, protecting coastal property from erosion and coastal storms, and protecting vulnerable populations during extreme heat events. He called for building assessments around these identifiable problems. He introduced a new approach to assessment, called applied assessment, focused on the identified needs for community adaptation and mitigation. New climate assessments need to reorganize around communities’ issues, identify what questions to assess (e.g., scientific, economic), and identify useful data. A key issue for applied assessment is identifying what is generalizable, what data is actionable, and what communities can learn from each other. To further improve and sustain assessments, Moss recommended a new institution: a civil society climate assessment consortium. This group would incorporate the best science with tested practices from decision makers across civil society, which would complement federal efforts. The group would encourage collaboration, balance needs and interests of different actors, and encourage collaborative governance, transparency, and scientific integrity. Moss saw the NCA as the gold standard for an open, collaborative, documented input process.

LOUISE BEDSWORTH, CALIFORNIA STRATEGIC GROWTH COUNCIL

Bedsworth described how California is sustaining its climate assessment efforts, which have been critical to support decision making in California. The first climate assessment aimed to understand statewide impacts of climate change, and supported policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It was taken by stakeholders to

Sacramento, where it became an important driver for passage of California Assembly Bill 32, the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 (see Table 1.1).4 In addition to being used by stakeholders to inform legislation, the assessments laid the foundation for the state’s 2009 California Climate Adaptation Strategy5 and the 2015 Climate Change Research Plan for California (CAT, 2015). Recent outcomes include incorporating current climate assessment conclusions into the state’s infrastructure plan and local safety plans. The assessment community is focused on making the assessment accessible and usable across the state’s nine regions, including through building and sustaining the Cal-Adapt tool. Bedsworth explained that a challenge to sustaining their efforts includes securing funding for institutionalization of tools like Cal-Adapt.

People will be central to evolving and sustaining California’s climate assessments, said Bedsworth. The issues that arise include governance challenges such as complex jurisdictional relationships and cascading events, as well as social disparities and inequities in capacity and resources for mitigation and adaptation. Looking ahead, key areas for sustainability of assessment include cross-sectoral work in communities where people live, climate justice and equity, production of actionable information, delivering support at the state and local level, and evaluation and monitoring of assessment. To turn assessment into action, important areas for growth include integrating climate assessment into planning, and evaluation and monitoring progress.

PANEL DISCUSSION

Bruce Riordan asked how assessments deal with “surprises,” problems that we have not anticipated. Reidmiller referenced the final chapter of the National Climate Assessment climate science special report, which addresses the impact of changes to the physical earth system that may happen on top of one another, or that may represent tipping points (USGCRP, 2017, Chapter 15). Reidmiller answered that a chapter in Volume II will look at sectoral interdependencies and cascading events that may disrupt people’s lives (USGCRP, 2018, Chapter 17).

Craig Zamuda suggested that assessments should begin to focus on managing risks. He asked whether there was adequate consensus and support for updating standards on resilient infrastructure, and if there were any priorities for filling key gaps. Bedsworth described a California working group on climate smart infrastructure and its guidance document, which does not recommend standards, but does help communities plan responses to needs, including developing their standards. The assessment community is also working with the department of general services to build climate change into design, such as into financing of investments. Moss suggested that partners in professional societies continue to work with assessment experts to write updated standards. He added that a new community of practice is needed to bring together disciplinary experts, climate experts, and other professionals to use climate science for planning and action. Jurado described challenges for local governments that want to implement different building or energy codes than those at the state or national level. Diaz shared the challenge of determining operating standards and planning metrics for high-consequence, low-probability resiliency threats. The assessment community could help inform the practitioner community in that area.

Paul DeCotis asked what outcomes and successes grew from assessments, beyond advances in science. Moss shared that people are already making better investments and better decisions based on climate change information, and that he believes we are already seeing outcomes from climate assessments. Bedsworth indicated that California’s assessments rely on connection to users, which has resulted in science information informing science-based policies. Jurado applauded the impressive assessment efforts ongoing in many state and local levels but was disappointed that there is often no end user poised to take the results. Government decision making tends to move slower than the science, she said, and the lack of policy uptake represents missed opportunities to mitigate and adapt, in turn leading to unnecessarily increased exposure and financial strain. She suggested that if assessments are updated every 5 years, then policies should be updated on a coordinated 5-year timeline. Diaz shared that most communication happens during development of assessment and in the immediate release period, but that the community could benefit from sharing collected success stories or secondary analysis as outcomes are realized.

___________________

4 California Air Resources Board, “Assembly Bill 32 Overview,” reviewed August 5, 2014, https://www.arb.ca.gov/cc/ab32/ab32.htm.

5 California National Resources Agency, 2009 California Climate Adaptation Strategy: A Report to the Governor of the State of California in Response to Executive Order S-13-2008, http://resources.ca.gov/docs/climate/Statewide_Adaptation_Strategy.pdf.

REFERENCES

CAT (Climate Action Team). 2015. Climate Change Research Plan for California. California Environmental Protection Agency. February. https://www.climatechange.ca.gov/climate_action_team/reports/CAT_research_plan_2015.pdf

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) National Centers for Environmental Information. 2017. “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters.” https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/.

State of California. 2018. California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment. http://www.climateassessment.ca.gov/.

USGCRP (U.S. Global Change Research Program). 2017. 2017: Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume I (D.J. Wuebbles, D.W. Fahey, K.A. Hibbard, D.J. Dokken, B.C. Stewart, and T.K. Maycock, eds.). doi: 10.7930/J0J964J6. http://science2017.globalchange.gov.

USGCRP. 2018. Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II (D.R. Reidmiller, C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, K.L.M. Lewis, T.K. Maycock, and B.C. Stewart, eds.). doi: 10.7930/NCA4.2018. https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/.