4

The Work of the Intelligence Analyst

The key function of most intelligence analysts is to make sense of information about the world that can be used to protect the United States. Intelligence analysts across the nation’s security agencies perform many tasks and play many roles, in line with the missions of their agencies, and they rely on diverse skills and experience as they carry out their responsibilities. Though many aspects of the agencies’ work are not open to public view, the general functions and activities of the intelligence analyst can all be regarded as aspects of sensemaking—using their expertise to seek understanding within the range of material to which they have access.

This chapter sets the stage for the discussion in Part II of opportunities to use social and behavioral sciences (SBS) research in support of intelligence analysis by describing the daily work of the analyst. Before proceeding, we note both that many aspects of the analyst’s work are classified and that the analyst’s job varies significantly across agency and function, so we could not be certain as to exactly where new research could augment, improve, or supplant strategies and tools already in use. However, the experience of many of the committee members, supplemented by what we heard in our public meetings (see Chapter 1 and Appendix B) and what we discerned from publicly available research, was the basis for the overview that follows.

SENSEMAKING

Much of the analyst’s work is primarily tactical; that is, analysts provide timely, high-quality insights to support immediate decision making

by the president, senior policy makers, Congress, the military, and law enforcement. To develop these insights, analysts need to digest large quantities of information that comes from both sensitive intelligence sources—obtained by human and technical means—and openly available sources. A primary, ongoing challenge is to identify and assess information that is relevant, thorough, and timely enough to support the development of high-confidence, accurate insights that will allow U.S. policy makers to mitigate risks or position the United States to exploit opportunities. It is this assessment—or sensemaking process—that yields intelligence, as opposed to raw information.

In practice, the distinctions among types of intelligence are not crisp, but, as discussed in Chapter 2, intelligence work also includes strategic analysis, intended to help policy makers understand the broad factors or dynamics that may be shaping a geopolitical situation. The objective of this kind of analysis is to look ahead in time, to identify connections among issues, and to set particular choices that must be made within a wider context of space and time. The challenge of strategic analysis is that it often begins where the immediately relevant information ends, so the analyst relies on history, logic, and perhaps theory in looking at trends and building scenarios that can offer insight about the future.

Observers and members of the Intelligence Community (IC) have raised concern about a perceived ongoing shift away from strategic intelligence in favor of current, tactical work (see, e.g., Johnson, 2011). After nearly a generation of fighting wars—which calls for a sharp focus on the immediate—strategic analysis has not been a high priority for the U.S. IC. It is carried out primarily within the National Intelligence Council and in pockets within other agencies, especially the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and as a consequence, the capacity to perform strategic analysis has lagged behind tactical capabilities (Treverton and Gabbard, 2008; Stimson and Habek, 2016). The pressure to balance the two is not new, and there has been a growing need for shorter, more digestible products in response to pressing problems, perhaps at the expense of in-depth research.

We use the term “sensemaking” not to constrain the description of intelligence analysis but rather to convey its intellectual breadth. The challenge of sensemaking for intelligence analysts is akin to challenges faced by analysts in other sectors, such as business, risk analysis, or urban planning.1 The need to find meaning in complex, data-rich environments and to understand especially challenging—“wicked”—problems is not unique

___________________

1 This meaning of the term “sensemaking” was introduced in the context of organizational science (Weick, 1995; see also Anacoda, 2012).

to the IC.2 The activities and responsibilities associated with intelligence analysis are similar to those needed for any planning or analytical task that requires expertise, the consideration of multiple variables across time and space, and the assessment of human behaviors and actions. Analysts seek to recognize patterns in behaviors, trends, and relationships among actors. Several experts have compared the work of intelligence analysts to that of medical diagnosticians because of the uncertainties involved, the complex interplay among factors, and the existential importance of the task (Marrin and Clemente, 2005; Treverton and Agrell, 2009).

Another possible comparison would be with making predictions about the performance of stocks. Stock analysts must consider diverse factors that may include trends within a single industry, as well as related industries whose fortunes may affect the one in question; the decision making of corporate leaders, consumers, and possibly policy makers in the United States and abroad; broad economic forces and trends; and even such external events as extreme weather or other consequences of global climate change, social trends, or fads. The investment analyst often must make quick decisions about the benefits of buying or selling stocks, knowing that the relevant information is limited, when potentially very large sums of money could be gained or lost.

In the context of the IC, sensemaking is a process of creating situational awareness and understanding in highly complex, emergent, or uncertain circumstances. One formulation characterizes intelligence problems as ranging from “puzzles,” or challenges that have solutions; to “mysteries”; to the most difficult problems, or “complexities” (see Table 4-1) (Treverton, 2009, p. 6).

IC analysts monitor and detect events and changes in the world, anticipating likely changes and forecasting future events. They use sensemaking capabilities at the macro and micro levels and across different cultures, societies, and organizations. For IC analysts, sensemaking is used to make sense not only of the actions and motivations of humans (individuals, groups, and societies) but also of the actions and drivers of nonhumans, such as technologies, robots, organizations, and other entities.

WHAT ANALYSTS DO

Most intelligence analysts have an area of responsibility—an account—that, depending on the size and mission of the parent organization or team, may be quite broad (e.g., China’s Communist Party) or more narrow (e.g.,

___________________

2 The term “wicked problems,” also introduced in the context of organizational management, refers to problems that are unusually challenging and difficult to define and solve, and involve complex competing factors that are difficult to reconcile.

TABLE 4-1 Puzzles, Mysteries, and Complexities

| Type of Issue | Description | Intelligence Product |

|---|---|---|

| Puzzle | Answer exists but may not be known | The solution |

| Mystery | Answer contingent, cannot be known, but key variables can, along with sense for how they combine | Best forecast, perhaps with scenarios or excursions |

| Complexity | Many actors responding to changing circumstances, not repeating any established pattern | “Sensemaking”? Perhaps done orally, intense interaction of intelligence and policy |

SOURCE: Treverton and Agrell (2009).

the life patterns of a particular terrorist leader). The account may lend itself more to qualitative analysis, of such questions as “How is leader X thinking about issue Y?” Or it may be more approachable through quantitative analysis, of such questions as “How much will India’s economy grow over the next 10 years?” As these examples suggest, many if not most of the issues examined by intelligence analysts are also topics of study in the public domain, and analysts draw on academic research from many SBS disciplines, although mechanisms for their doing so are not as well established as they could be to serve the IC’s needs, an issue discussed in Chapters 9 and 10.

Many analysts have deep expertise in their account, having studied it at the undergraduate or graduate level and worked on the issue professionally for many years. In the past two decades, many universities have begun to offer undergraduate degrees in intelligence studies, although there is ongoing discussion about the extent to which intelligence analysis should be regarded as an academic discipline (e.g., Fisher et al., 2014), and some critics have suggested that prospective analysts are better off majoring in SBS fields, languages, and other academic disciplines (Dujmovic, 2016).3

Not all analysts have deep expertise in specific areas relevant to their accounts, either because they are just starting their professional careers or because changing job responsibilities require changes in focus. The broad nature of national security requires expertise in a wide variety of topics, not all of which are in high demand as university majors. Thus, available

___________________

3 Attention to the demands on members of the IC and how young people might best be prepared and selected for this work has also led to debates over whether intelligence analysis should be considered a profession or a craft (Gentry, 2016). This question is outside of the committee’s charge, but we regard the work of the analyst as having elements of both categories.

intelligence staff may not bring all of the expertise relevant to some analytic accounts. It is possible, however, for analysts to develop expertise in particular types of intelligence problems, by, for example, working on several countries during crises.

Regardless of these differences, virtually all analysts—whatever their assigned account—engage in multiple activities. They circle back and repeat activities, and often, because of time pressures, omit certain actions entirely. Many of these activities are also performed in a team environment, with individual analysts sharing responsibility for the tasks involved, although it is not unusual for an individual analyst to perform most if not all of these activities herself (see Chapters 7 and 8 for further discussion of teaming; see also Hackman and O’Connor [2005]). Our description highlights primary functions common to most analysts’ work. We look first at the recurring activities that are part of day-to-day responsibilities, then at sustaining activities through which analysts pursue the longer view of their accounts. We then look at a key element of any type of analysis, one that is both a daily and a sustaining activity: communicating it effectively so that clients can act on it.

The Analyst’s Daily Activities

Maintain an Inventory of Questions That Are Important for the Analyst’s Assigned Account

Analysts need to identify and track questions that reflect both their understanding of what policy makers want to know and their own appreciation of the issue at hand. They are not passive receptors of information provided by the agents who collect it and other sources; they provide parameters to help collectors focus on obtaining information that is key to narrowing intelligence gaps, and like social scientists, they help shape the design of data collection efforts. This is a foundational task: if analysts do not ask the right questions, they are likely to miss important developments on their accounts. This inventory of questions will span the range of puzzles, mysteries, and complexities, often fluctuating among them. Not infrequently, for example, a question that an analyst believed would lend itself to a linear answer—i.e., a puzzle—will reveal itself to be more complex, making it difficult to disentangle causal factors.

The analyst’s inventory of key analytic questions will cover a wide range of topics. On any given day, analysts will be dealing with specific questions, such as “What is Individual X likely to do tomorrow?” But these specific questions will most often fall into more general areas of study and investigation.

Understanding power. How are decisions made in a nation, society, group, or organization? How is status allocated? Is the nature of power changing? What are the important sources of power in a particular context: economics, military might, corruption?

Understanding influence. What are the centers or networks of influence in a nation or organization? How is that influence wielded? What types of themes, narratives, and communications are influential in a society? What opportunities exist to influence a particular individual or group?

Understanding threats, opportunities, and social and organizational dynamics. What are the variables that threaten the cohesion and stability of a particular organization or society? What opportunities would the group or nation welcome and seek to take advantage of? What are its priorities, and how might they change? How stable is a particular group? What indicators should be used to track change?

Understanding complexity. Which developments are difficult to explain? What new dynamics may be emergent in a society or organization? How do seemingly disparate events combine to form new realities? What are the network effects? Which situations appear uncertain and difficult to parse—that is, wicked problems?

Understanding deception and gaps. How complete are the reporting and information available on an issue. How can the information be validated? Are certain sources of information suspect? What information is missing? What reporting appears to be “too good to be true”?

Stay Abreast of Current Information Relevant to the Account

Information of interest to the analyst includes classified intelligence collected on the account (e.g., through clandestine reporting, diplomatic reporting, or signals intelligence [SIGINT]), as well as any other information that might be relevant to the account. Indeed, defining what is relevant is itself a significant task that depends on the judgment and experience of the individual analyst. Thus, staying abreast of information involves several subactivities.

Establishing parameters and routines for information or intelligence searches. For example, the analyst may develop a search query for automated information-retrieval software or devote time each week to researching public sources and academic literature. The establishment of an information routine helps the analyst determine whether she is keeping

up with the information flow or falling behind. The information routine requires monitoring and updating.

Filtering information and intelligence to determine what is deserving of more careful study. For an intelligence analyst responsible for a broad account, such as following the outlook for a particular leader, filtering what to pay attention to can be a particularly difficult, though critical, activity. How does the analyst, for example, know which popular cultural themes are important to follow? For an analyst dealing with a highly specific, narrow issue, such as the activities of a particular military unit, filtering information flow may be more straightforward, but even here, broader context may be necessary to understanding the unit’s movements and actions. For example, how might the conditions of roads or timing of religious holidays affect the unit’s mobility?

Filtering information with speed and accuracy is critical as no analyst wants to miss an important development because she did not spot the information. Yet for almost any account, the flow of possibly relevant information is so great that the analyst’s tools and strategies for filtering are critical. Analysts often rely on filtering for the titles or subject headings assigned to discrete information items. This practice becomes problematic, however, when the originators of information describe its content or significance incorrectly. Technology can help, both in filtering and in tracking what has been filtered out in case it becomes valuable later, as discussed in subsequent chapters.

Reading selected information for understanding and meaning. Analysts take in a significant portion of their information by reading and must quickly digest large volumes of text. Reading strategies naturally vary with cognitive styles: some analysts may read important content several times, taking notes and underlining; others may read only once and move on. In many teams, analysts engage in substantive back-and-forth as they read through their information. “Did you see that report from the embassy? What do you think?” Analysts’ exchanges about the information they are reviewing are a key way that they confirm assessments of credibility and other questions. Regardless, reading large volumes of material has long been a constant for most analysts.

Making judgments and evaluating the information received. Each day, sometimes every hour, an analyst will encounter new content that requires evaluation. “Is this information new? How important is this information? How should it be categorized? Is it relevant to the motivations of a leader or the interaction between two countries? Is it ‘good’ or ‘bad’ news for a particular terrorist group? Does it conflict with other information? If so,

what evidence could indicate which is correct? Does this information make a bad development more or less likely? Is it unusual for this company to sell this material to country Z?” These are only examples of the hundreds if not thousands of potential questions the analyst may have to answer. Often an analyst may gain perspective on particular content only by combining it with other items of information or knowledge; for example, the fact that individual Y went to location X yesterday indicates that last week’s report of an important leadership meeting may be true.

Thus, pattern recognition is a key element of the analyst’s judgments about the information received, as is sensitivity to nonobvious indicators of change. Understanding of social and cultural factors is key to the analyst’s capacity to search for, understand, and combine information intelligently, as are such skills as managing, coordinating, and combining information from multiple sources.

Cataloging the information. New content may need to be parsed into discrete information items to maximize its utility. A reporting cable, for instance, may have to be broken down into who, what, where, and when before its import can be entered into a database, or an analyst may maintain a descriptive list of a terrorist’s daily habits that requires updating. In some units, information may be catalogued in a formal manner, perhaps being entered into a database shared by a team or an entire organization. In other cases, however, an analyst may catalog information only in his own mind, relying on memory to bring it forward when needed, or in simple records, such as chronologies of events.

Sustaining Activities

Apart from sorting through information and preparing intelligence reports, analysts, like any professionals, must engage in other activities just to maintain their expertise and advance their craft.

When—or perhaps if, given the tyranny of the present—intelligence analysts are not addressing time-sensitive issues, they will likely turn their attention to medium- or longer-term projects, such as researching a report on the emergence of a new leader in Cuba or working with an analytic methodologist on a new application of link technology that can elucidate the leadership structure of a terrorist organization. Analysts always need more time to gather information and explore new sources. An analyst may want to visit several policy makers or other clients to remain current on their intelligence needs, or meet with a collector of human intelligence (HUMINT) or SIGINT (see Chapter 2) to update intelligence requirements on a particular issue.

There are resources on which analysts can rely to supplement their own information, perspectives, and tools, such as security contractors,

experts at think tanks, and university researchers. However, it is not easy for intelligence analysts to conduct independent research, such as field work to determine attitudes toward particular issues in a country they are following, in their areas of responsibility. Public perceptions of the intelligence function, along with administrative and sometimes even legal restrictions, limit the analyst’s activities.

Finally, to do their jobs effectively and efficiently, analysts need to work with a model, a theory, or a set of hypotheses concerning their account. It is in fact this set of hypotheses that helps determine the analytic questions that frame the analyst’s work (i.e., the first step in the analyst’s daily activities). For example, an analyst may believe that country W is relatively stable or, conversely, is about to enter a volatile period. This framework will then color how the analyst sorts and interrogates the daily flow of information. Or a technical analyst will have a sense of new scientific breakthroughs in his or her field and thus be actively looking for the first signs of their adoption by a particular military. Developing such heuristics, updating them on a regular basis, and refining analytic questions are the steady baseline activities for the analyst. Individual analysts and teams of colleagues continuously review and develop the theories and models that provide fundamental support for intelligence analysis. Structured analytic techniques based in the scientific method can help analysts organize their thinking about the conceptual underpinnings of their work, achieve clarity, and document uncertainties and gaps; these formal structures are the predominant way of framing analytic methodology within the IC (Heuer, 2011). Throughout these processes, proficient analysts and analytic teams will examine their worldviews, their cognitive biases, and their sources of information to identify weaknesses and apply corrective measures.

Communicating Intelligence and Analysis to Others

Effectively communicating to policy makers the information it is critical for them to have is as fundamental as developing and assessing the information in the first place. If the analysis is to be useful, it must provide sufficient context to support clients in making sound decisions, as well as a realistic, accurate indication of risk and urgency. It is also critical that the analyst (or analytic team) have the trust of the client and establish a rapport that facilitates communication (see, e.g., Hulnick, 2007; Lowenthal, 2017; Davis, n.d.). This is accomplished through informal interaction between analysts and their managers and networks of counterparts at the Departments of Defense and State, through feedback mechanisms built into the President’s Daily Brief process, and in other ways both formal and informal.

Questions about what is done by policy makers in response to assessments provided by analysts are beyond the scope of this report, but a key aspect of analysts’ responsibilities is to ensure that their intended messages

are heard and understood. At the same time, particularly when the analysis pertains to serious or immediate risks, analysts bear a grave responsibility in considering how to convey the level of risk in a way that is actionable—providing any available guidance about possible responses—without usurping the decision maker’s role (see Johnson, 2011; Davis, 2015; Wirtz, 2019; Wolfberg, 2017).4

As analysts absorb information, they must decide whether some of it needs to be communicated to others and if so, when and how. Analysts may be instructed to prepare intelligence reports for managers who also review the intelligence and information flow on a daily basis, or they may receive questions from policy makers. Analysts may also encounter unexpected information they recognize as important to convey to others. Their communications may be as simple as sharing their view of a particular piece of content with their teammate—for example, “This reporting looks new, but we actually saw the same information from another source 3 weeks ago.” Or the task may be as obvious as the need to communicate a report of plans for a terrorist attack against a U.S. embassy to the National Security Council.

What is important to note here is that much of the information being parsed by the analyst is also being seen by hundreds of other members of the national security community. Information about a threat to a U.S. embassy, for example, would be sent to the embassy, to the White House Situation Room, to the responsible military command, and possibly to others as well. More sensitive reporting may be seen only by a few colleagues, and perhaps shared only through the President’s Daily Brief. In any case, it is rare for an analyst to be the only individual to see a report, although he may be the first or only person to understand its significance. Others may not regard the threat of an attack as credible, for example, but the analyst may realize that the details of the attack are identical to those in a report from weeks ago about a terrorist group’s plans to change tactics. As with the task of keeping up with the flow of information, many subactivities are involved in communicating intelligence to others.

Preparing an intelligence report. The nature of this report will vary with the organization, the urgency of the report, and the audience to whom the information is to be reported. The report may be a slide in a PowerPoint briefing, an updated coordinate on a map, a cable sent to the field, or a

___________________

4 Research on the communication of risk, much of it developed in the contexts of public health and climate change, provides insights on how to communicate about the likelihood and potential impact of negative events (see, e.g., the Journal of International Crisis and Risk Communication [https://stars.library.ucf.edu/jicrcr] and Journal of Risk Research [https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rjrr20/11/1-2]).

formal piece of intelligence analysis for the President’s Daily Brief. It may be transmitted in a phone call or a classified email. If a formal, written report is necessary, a premium is placed on the quality and conciseness of the writing. Reports also need to be tailored to suit the preferences of the client: one policy maker may prefer to receive intelligence summarized, with the main points on a single page, for example, while another may prefer graphics.

Coordinating and collaborating with peers. If an analyst has a discrete account—perhaps being the only individual following events in a small country—there may be little need to discuss her findings with others. More typically, however, analysts will need to coordinate their intelligence reports with other analysts who cover the same or related issues. An intelligence report on North Korea’s use of a new port in Oceania to evade military sanctions, for example, will have to be coordinated with the analysts covering North Korea and those covering Oceania, as well as with imagery experts, military analysts, experts on sanctions, and experts on port operations, just to name the most obvious. The earlier such coordination occurs, the more profitable it is likely to be. Often, however, the press of business leads to a compressed, hurried process. It is not unusual for coordination steps to be missed for a rushed item; this may in fact be a good outcome if a military commander in the field just needs a quick update. Analysts may also be unaware of individuals who could have added useful information or perspective on an issue, as is particularly the case when the coordination is occurring across agencies within the IC.

Sourcing the intelligence report. The analyst needs to assemble the most important intelligence and information that is the basis of the findings to be conveyed to others, particularly policy makers, in a formal report. This task can be time consuming for an analyst, particularly if the findings are based on multiple reports that must be interpreted in a particular way or sequence if they are to be understood accurately. Clear sourcing is important both for coordinating intelligence within the analytic community and for conveying accurate information to policy makers, who may not on their own make connections in the same way the analyst will. Another complication arises if intelligence reports are particularly sensitive and require specific approval to be shared with a broader audience.

Shepherding the intelligence report through an editorial process. Depending on the nature of the intelligence report, the analyst may need to engage with a complex editorial process designed to ensure the quality of what is essentially an organizational product. The editorial process for the President’s Daily Brief is particularly complex because of the importance of its clients (the president and a very small number of aides and cabinet

members). The layers of the process typically include, but are not limited to, the analyst’s immediate supervisor; the leader of the analytic office; a chief editor with duties not unlike those of a newspaper or journal editor; and in the case of the President’s Daily Brief, a senior reviewer representing the leadership of the IC. The analyst’s job is to defend the analysis itself from editorial “fixes” that would alter the message while at the same time welcoming changes that improve clarity and readability. The analyst must also be sensitive to editorial changes that would require further coordination with colleagues. It is important to note that this editorial process is not merely or even primarily stylistic; it often identifies errors in thinking or perspective that need to be fixed. For example, it is not unusual for a reviewer to identify new experts who must be consulted to complete an intelligence report. More senior editors will be more sensitive to how a particular judgment can best be communicated to a skeptical policy maker.

Finalizing secondary details. In most IC organizations, analysts are also responsible for many auxiliary details in the communication of an intelligence report. The analyst may need to coordinate with the graphic designer to develop visuals that accurately convey the information, or create derivative versions of the report to share with a broader audience not cleared to receive the original. The analyst may need to identify the proper list of recipients for particular reports.

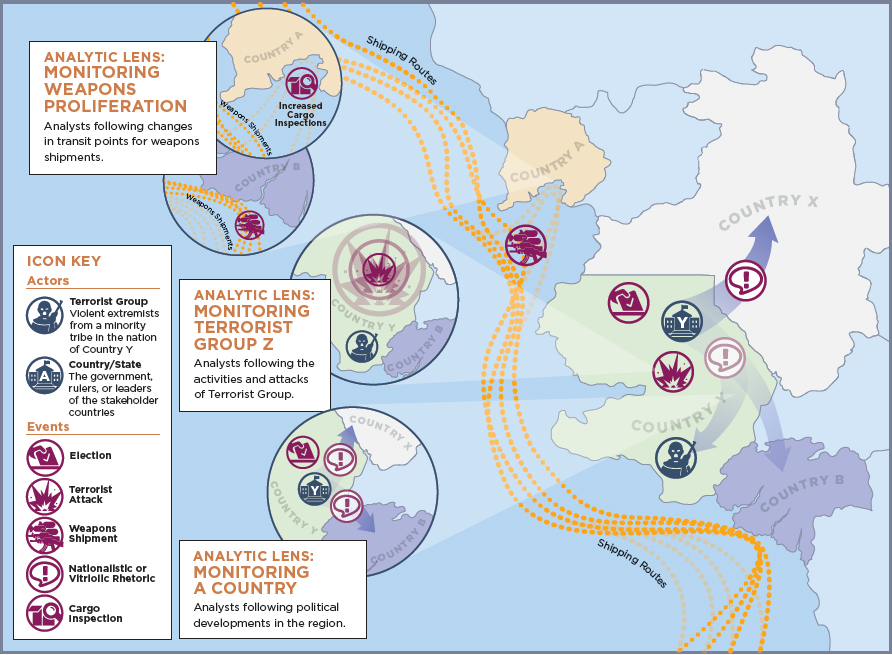

ILLUSTRATING ANALYTIC WORK

In discussing the opportunities SBS research offers, in Part II, we point to many aspects of the analyst’s work that may not be entirely familiar to readers not directly involved in the work. To help make the applications of the research described in Part II come alive, we developed a hypothetical illustration of one aspect of intelligence analysis. As noted above, analysts must naturally focus on particular aspects of the world, and of necessity can apprehend only fragments of the entire picture at a time. Figure 4-1 illustrates several of the many possible lenses through which teams of analysts might view the world, depending on their areas of subject matter expertise and the accounts to which they have been assigned. The figure depicts a set of circumstances that teams of analysts might be following. We developed a stand-in map to avoid association with any actual geographic region, but note that the hypothetical circumstances illustrated are simpler than any real-world example would be.

In the region depicted, a number of circumstances and current developments can be observed:

- Terrorist group Z is conducting more frequent complex attacks against government installations in country Y.

- Country A has increased the rigor of customs enforcement, including cargo inspections.

- Weapons proliferators have changed transit points for weapons shipments to country B.

- Country Y’s leader has increased negative rhetoric aimed at country X to shore up nationalist support in advance of national elections.

Different teams of analysts regard this region and these developments through different lenses, based on the accounts for which they are responsible.

Analytic Lens: Monitoring Terrorist Group Z

Analysts who focus on terrorist groups work to detect patterns in information they collect about the movements such groups make and their communications. In Figure 4-1, a group of analysts closely follows terrorist group Z, which is conducting attacks against government installations in country Y. While terrorist group Z acts independently, it is known to have a close relationship with country X, with which it shares cultural and religious beliefs. The analysts have observed over time that both terrorist group Z and country X see country Y as an existential threat because of its differing cultural and religious beliefs, capable military, and history of aggression. The analysts have been using an all-source data aggregator to capture all possible information on terrorist group Z’s attacks, past and present, to identify patterns in the attacks. The results show that terrorist group Z’s attacks against country Y are growing more complex, using powerful explosives and sophisticated detonation techniques. The analysts following terrorist group Z might decide to collaborate with those responsible for country X to determine whether the explosives’ components are consistent with materials in that country’s military arsenal, and, if this is confirmed, make the judgment that country X is providing material support and training for terrorist group Z.

Analytic Lens: Monitoring Weapons Proliferation

In Figure 4-1, weapons proliferation analysts, using algorithms to detect changes in transit points for weapons shipments, detect a change in shipping routes for weapons, weapons components, and other weapons-related materials. Shipments that had been transiting through country A are now transiting through country B. The analysts have assembled information on which countries and groups possess the technology to sell weapons,

which have a need to buy them, and how supply chains for such weapons work. They note that country A has stepped up cargo inspections under international pressure and assess that weapons suppliers have likely identified country B as an attractive alternative transit site in the region because it requires less stringent inspections.

Analytic Lens: Monitoring a Country

Analysts who follow political developments in the region depicted in Figure 4-1 notice that the leader of country Y, who has been in power for 20 years, is facing National Assembly elections later in the year. They know from experience that he has traditionally used carrots, sticks, and low-level fraud to ensure a credible majority win for his party. The analysts discern in both intelligence reporting and open-source information that dissatisfaction with his rule is growing, and that he is increasingly preoccupied with tactics that will ensure a favorable election outcome that will be viewed as legitimate by the electorate. The analysts also know that the leader of country Y has historically used nationalist rhetoric directed at country X and terrorist group Z to shore up his base of support and justify cracking down on his domestic opposition; for example, he has publicly accused opposition leaders of colluding with terrorist group Z. The analysts are using algorithms to track the content of this leader’s rhetoric over the past 6 months; their results show a major spike in negative themes involving country X, with a lesser uptick in vitriol against both terrorist group Z and a small neighboring country, country B. Since the vitriol against country B is an anomaly, the analysts may continue to focus their efforts on what experience has shown: that the leader of country Y is stirring up nationalist sentiment against country X to deflect criticism of his government’s handling of the attacks by terrorist group Z and shore up his party’s chances in the elections.

LOOKING FORWARD

The roles and tasks of intelligence analysts described above are classic ones, and they still apply. Analysts continuously develop new technical skills to support their analysis, but the fundamental nature and demands of the job have not changed significantly in the past few decades. Yet the world of the analyst is changing as the world itself changes. Of the changes that affect the analyst’s world, the most obvious is perhaps the combination of transparency and overabundance brought by big data. A proliferation of sensors continues to dramatically increase the volumes of information that, in principle, make so much more information visible to the analyst. Advances in information technology have made it possible to harvest

meaningful information from those enormous volumes. As researchers in SBS fields continue to generate new findings, the challenge of staying abreast even with, say, the literature relevant to terrorism or weapons proliferation increases weekly. Analysts struggle to make sense of a high—and constantly increasing—volume of both clandestine and openly available information. Some still worry that vital information that governments and nonstate actors take great pains to conceal is still being missed. Principal Deputy Director for National Intelligence Sue Gordon recently characterized the challenge this way (Gordon and Long, 2017, p. 4):

We’ve moved from a world of data scarcity to data abundance. Where we used to go looking for single pieces of information that no one else had . . . now what we have is a world that is so much information that we have to make sense of it. How do you take advantage of the data that is now available and do something special with it so we know something a little more, a little sooner? We have to help the community build more capacity, whether that’s in artificial intelligence, or in cyber, capacity and capability . . . to make use of all the data that exists.

A second set of big changes is likely in the nature of what analysts produce and how it is conveyed to their policy clients. The IC will continue to produce exquisite analyses, but rapid growth has occurred in commercial products and services that could be adapted to support intelligence analysts. For example, many of the kinds of products being produced by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency a generation ago are now available commercially, or even for free on the Internet (National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, n.d.). Intelligence analysts will continue to search for new ways to add value that will intersect with policy makers’ need for 24-7 access to intelligence.

As a result, the “product” of intelligence will increasingly be the analytic teams themselves, connected by new technologies to their policy counterparts and finding innovative ways to answer questions. This change will drive corresponding changes in how analysts are selected and how they are trained and evaluated. Analysts will surely need more quantitative skills so they can be sophisticated consumers of big data analytics;5 they will also need to be adept not only at providing briefings but also at interacting with policy officers ad hoc.

___________________

5 Data analytics allows for the identification of relationships and patterns across large and distributed datasets (Floridi, 2012) such that fine-grained behaviors and preferences (e.g., political opinions) can be tracked, and predictions about future behavior can be made (e.g., predictive policing or screening for insurance or employment) (Mahajan et al., 2012).

REFERENCES

Anacoda, D. (2012). Sensemaking: Framing and acting in the unknown. In S. Snook, N. Nohria, and R. Khurana (Eds.), The Handbook for Teaching Leadership: Knowing, Doing and Being (pp. 3–20). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Davis, J. (n.d.). A Policymaker’s Perspective on Intelligence Analysis. Available: https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/kent-csi/vol38no5/pdf/v38i5a02p.pdf [February 2019].

Davis, J. (2015). Intelligence analysts and policymakers: Benefits and dangers of tension in the relationship. In L.K. Johnson (Ed.), Essentials of Strategic Intelligence (pp. 115–138). Santa Monica, CA: Praeger.

Dujmovic, N. (2016). Colleges must be intelligent about intelligence studies. The Washington Post, December 30. Available: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2016/12/30/colleges-must-be-intelligent-about-intelligence-studies/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.9bfb3a41274b [November 2018].

Fisher, R., Johnston, R., and Clement, P. (2014). Is intelligence analysis a discipline? In R. George and J. Bruce (Eds.), Analyzing Intelligence: National Security Practitioners’ Perspectives (2nd ed., pp. 57–80). Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Floridi, L. (2012). Bid data and their epistemological challenge. Philosophy & Technology, 25(4), 435–437.

Gentry, J.A. (2016). The “professionalization” of intelligence analysis: A skeptical perspective. Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, 29(4), 643–676. doi:10.1080/0885060 7.2016.1177393.

Gordon, S., and Long, L. (2017). Plenary Session #6: A Conversation with Sue Gordon. Presented at the Intelligence and National Security Summit 2017. Available: https://www.insaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Summit-2017-Transcript-Sue-Gordon-7Sept2017.pdf [November 2018].

Hackman, J.R., and O’Connor, M. (2005). What Makes for a Great Analytic Team? Individual versus Team Approaches to Intelligence Analysis. Washington, DC: Intelligence Science Board, Office of the Director of Central Intelligence. Available: https://fas.org/irp/dni/isb/analytic.pdf [February 2019].

Heuer, R.J., Jr. (2011). Structured Analytic Techniques for Intelligence Analysis. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Hulnick, A.S. (2007). What’s wrong with the intelligence cycle. In L.K. Johnson (Ed.), Strategic Intelligence, Volume 2: The Intelligence Cycle (pp. 1–22). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Johnson, L. (2011). The Threat on the Horizon: An Inside Account of America’s Search for Security after the Cold War. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lowenthal, M.M. (2017). Intelligence: From Secrets to Policy, 7th ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Mahajan, R.L., Mueller, R., Williams, C.B., Reed, J., Campbell, T.A., and Ramakrishnan, N. (2012). Cultivating emerging and black swan technologies. ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, 6(Pts. A and B), 549–557.

Marrin, S., and Clemente, J.D. (2005). Improving intelligence analysis by looking to the medical profession. International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 18(4), 707–729.

National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. (n.d.). 2015 NGA Strategy. Available: https://www.nga.mil/About/NGAStrategy/Pages/default.aspx [November 2018].

Stimson, C., and Habeck, M. (2016). Reforming intelligence: A proposal for reorganizing the intelligence community and improving analysis. The Heritage Foundation, August 29. Available: https://www.heritage.org/defense/report/reforming-intelligence-proposal-reorganizing-the-intelligence-community-and [November 2018].

Treverton, G. (2009). Addressing “Complexities” in Homeland Security. Stockholm, Sweden: Center for Asymmetric Threat Studies (CATS). Available: https://medarbetarwebben.fhs.se/Documents/Externwebben/forskning/centrumbildningar/CATS/2009/publikationer/addressing-complexities-in-homeland-security.pdf [November 2018].

Treverton, G., and Agrell, W. (2009). National Intelligence Systems: Current Research and Future Prospects. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Treverton, G., and Gabbard, C.B. (2008). Assessing the Tradecraft of Intelligence Analysis. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Available: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2008/RAND_TR293.pdf [November 2018].

Weick, K. (1995). Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Wirtz, J.J. (2019). The intelligence-policy nexus. In L.K. Johnson (Ed.), Strategic Intelligence: Understanding the Hidden Side of Government (vol. 1, pp. 139–150). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Wolfberg, A. (2017). The President’s Daily Brief: Managing the relationship between intelligence and the policymaker. Political Science Quarterly, 132(2), 225–258.