3

Opportunities for Advancing Behavioral Health Equity Through State and Local Policy

Equity is the absence of avoidable, unfair, or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically or geographically or by other means of stratification. “Health equity” or “equity in health” implies that ideally everyone should have a fair opportunity to attain their full health potential and that no one should be disadvantaged from achieving this potential.

—World Health Organization1

The next workshop session featured policy makers at the state and community levels who described the role they play in achieving health equity for children and families. Mary Ann McCabe, George Washington University School of Medicine, and Kimberly Hoagwood, New York University, served as co-moderators of this session.

Beginning with the World Health Organization’s definition of health equity, McCabe asked the workshop participants to keep several principles in mind. First, she said, behavioral health and mental health are part of health. Second, a two-generation approach is important to achieve health equity, because helping parents in turn helps children. Thus, the subject of the workshop’s discussions at times might be parents or the adult caregivers, because the whole family aims to benefit from improved outcomes. Third, science can inform policy and policy can inform science.

Those working in the public health arena have an appreciation for the role that policy makers play when it comes to improving health and well-

___________________

being, Hoagwood said. She noted the social determinants of health are currently receiving a great deal of attention from the scientific community, but policy makers are also looking at the connection between social factors and health outcomes as they pertain to societal risks. However, one of the conundrums related to health equity issues and the relationship between health and social policy is that the systems in which children and families live are very segregated. Crafting policy that crosses some of these boundaries can be tricky, Hoagwood said. By struggling with these issues, policy makers are able to design universal approaches that can benefit large numbers of children and families.

The four presenters in the session were Anneta Arno, Office of Health Equity in the District of Columbia; Edward Ehlinger, Minnesota Commission of Public Health; Daniela Lewy, Virginia Governor’s Children’s Cabinet; and Joe Thompson, Arkansas Center for Health Improvement.

HEALTH IN ALL POLICIES

Anneta Arno said her office was established to look at health disparities beyond health care and health behaviors. Alongside the director of the health department, with whom she also worked in Louisville, Kentucky, Arno said she learned that an office of health equity could not work on its own. There needs to be an understanding of shared accountability for health equity across and beyond the health department. To achieve the mission, she began by informing, educating, and empowering people about values that define how they live. Multisector partnerships were key to identifying and solving community health problems related to the social determinants of health.

Arno explained four strategies adopted to ensure that health equity practice is a component of work outside the Office of Health Equity: (1) establish and support multisector partnerships; (2) promote health in all policies; (3) leverage community-based participatory research; and (4) demonstrate health equity practice change. She emphasized the need for practice change to shift focus from addressing health disparities to achieving health equity. Simply switching from one term to another is not enough, she said, commenting, “You are still doing the things you have always done, you are not having the impact that you need to have.”

Since 2015, Arno has spearheaded projects to improve health equity in Washington. Among them was the Safer Stronger Advisory Committee, launched in December 2015, which uses a public health approach for violence prevention. The committee focuses on addressing the root causes of violence and identifying ways to reduce incidents. Arno recounted that they do not see violence in communities happening because of “bad people,” but because people are “pushed too close to the edge. They’re about to fall over the cliff and take it out on others for some reason.”

Launched in 2016, the Buzzard Point Project was an effort that worked directly in the community when a new stadium was being planned for the D.C. United soccer team. Arno reported that initial strong community support for the stadium shifted once construction started and air quality declined from dust and other environmental irritants. Had the Department of Health solely looked at the metrics comparing Buzzard Point to the rest of D.C., it would have concluded that there was no statistical significance in terms of health outcomes. However, because of how the Office of Health Equity does its work, the department looked more closely at who was residing in the vicinity’s four census tracts. The average income across the census tracts, Arno explained, showed a neighborhood earning around $100,000 per year. However, one tract showed a drastically lower average income of $35,000 per year. With consideration of social barriers and protective factors, the advisory committee was able to conclude that those at the lower-income levels likely took more breaks from using air conditioning to curb costs, allowing dust to enter their homes when windows were opened. Ultimately, the problem was solved by providing low-cost improved air filters. This is one example of how to change practice, Arno said, by looking at the data differently to find a solution for those affected and who might otherwise be overlooked and underserved.

Another project was the Healing Future Fellowship, which trained high school students as “healing ambassadors.” Students received violence prevention training, including content about how violence starts and methods for how they can be ambassadors. The program was designed to engage average youths in the community, not the youths often seen as leaders. Each year, the fellowship graduates a cavalry of ambassadors who use violence prevention strategies and support resilience in the neighborhoods where they were raised and live.

Launched in 2017, the Commission on Health Equity was to reframe legislation not solely focused on health care and disease, but instead to think broadly about community prevention and community resiliency models. The commission expects to release a health equity report baseline assessment in the coming year. It will focus on the social determinants of health and build on lessons learned from projects like Buzzard Point to look beyond what is identified as a neighborhood to better understand why some residents have a disproportionately higher incidence of health issues.

THE TRIPLE AIM OF HEALTH EQUITY

Edward Ehlinger began his work in this area in 1980 when he served as director of the Maternal and Child Health Program in the Minneapolis Health Department. At that time, data showed the infant mortality rate (IMR) for black babies was more than twice that for white babies. Over

the next 30 years, the IMR was reduced by 50 percent across both populations; however, the disparities remained. “What this taught us,” Ehlinger explained, “is that the way we do our work has to change. . . . We have to have a theory of change.”

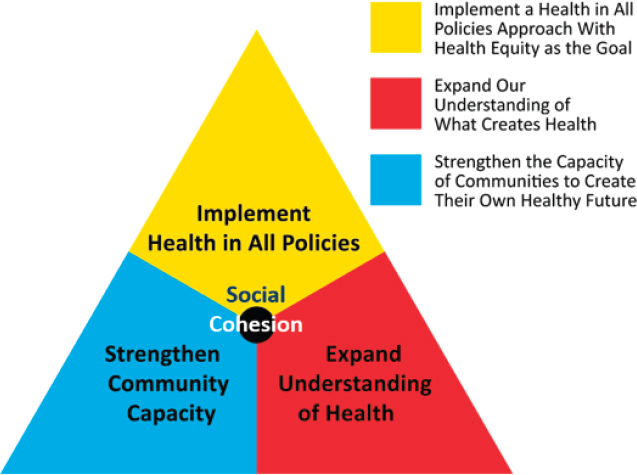

Ehlinger stated that change has to begin with community organizing and therefore needs to follow three organizing principles. First, he said, “We need to organize the narrative, we need to organize the resources, and we need to organize the people all around the idea of social cohesion.” From those organizing principles, he noted, comes the triple of aim of health equity that uses transformational practices to build power for advancing health equity and optimal health for all (see Figure 3-1).

Not to be confused with the triple aim of health care (which places medical care at its center), the triple aim of health equity differs by placing social cohesion at its center, Ehlinger clarified. He said that the health equity model starts with expanding an understanding of what creates health to essentially change the narrative. It goes beyond medical and personal choices and instead considers the conditions in which people live, work, and go to school that are impacted by public policies. He stressed, “What is good for health equity is not the same as what is good for health.”

Second, he said that it is necessary to implement “health in all policies” with health equity as a goal. There should be an understanding that health

SOURCE: Ehlinger (2017).

is not the responsibility of public health or medical care, but rather the responsibility of everyone—all systems have to be engaged, and equity has to be the goal. For example, Ehlinger explained, paid leave policies promote health and well-being. Yet, when full-time workers receive paid leave but part-time workers do not, disparities are enhanced.

Third is the need to strengthen the capacity of communities to build their own healthy future, said Ehlinger. When communities are engaged, they have a seat at the table, and that gives them power. There is a difference between having representation on certain issues and having power to make decisions on behalf of one’s self and community.

Ehlinger concluded that adverse childhood experiences do not emerge out of nowhere, but come out of societal conditions. The triple aim of health equity looks at these societal conditions and asks how to then change the things that impact childhood experiences. Instead of labeling diseases of disconnect and despair, strategies to change policies, systems, and the environment are needed, he said. That is how the triple aim of health equity helps frame the work of policy makers.

ACTION THROUGH COLLABORATION

Daniela Lewy is executive director of the Virginia Governor’s Children’s Cabinet, which consists of four secretariats (health and human services, education, public safety and homeland security, and commerce and trade), the first lady of Virginia, and the lieutenant governor/governor elect of Virginia. The cabinet was established to help align the policies and practices of more than 150 program and funding streams across the state, often bringing together communities, state agencies, and the private sector to support children.

As executive director, Lewy focuses on breaking down silos and not allowing government bureaucracy to hinder what is best for children. She explained she acquired this skill from her previous job with the Baraka School, a program that brought 7th- and 8th-grade boys from Baltimore to Kenya. She related the story of one of the Baltimore participants. Through his own initiative and with support from Lewy and many others, he received a scholarship to attend a private high school and enrolled at Frostburg State University. One night after playing football, he died from a heart attack. Although he received health care through Medicaid, he did not receive the same care as other college athletes. Lewy noted nearly 1,000 people attended his funeral, a diverse group of foundation leaders, educators, health practitioners, volunteers, students, and gang leaders. She said it occurred to her that many of those at the funeral would not normally interact with one another under normal circumstances, yet they were part of the young man’s success. The experience made her realize how systems could improve

the lives of larger numbers of children if they brought together the variety of supports needed. Her position with the Virginia Governor’s Children’s Cabinet does this, she said.

Lewy provided an overview of several Children’s Cabinet initiatives. The Challenged Schools Initiative starts with the assumption that the Department of Education is focused on teacher improvement, principal leadership, and curriculum, and the Children’s Cabinet can help with other crucial components like housing and jobs. The Classrooms not Courtrooms Initiative aims to disrupt the school-to-prison pipeline, a priority that emerged from data showing Virginia had some of the highest school referrals to law enforcement in the nation. Trauma-Informed Care to Address Adverse Childhood Experiences aims to align efforts across agencies. The cabinet is also creating a fiscal map that shows how the $6.27 billion allocated for children in Virginia is being invested. With success, the state hopes to address barriers of care and coordination across systems and support social determinants of health that promote equity for children.

GETTING TO FIFTY-ONE PERCENT

Joe Thompson described his role as both a tactician and strategist and noted he served as lead adviser to two governors—one Republican, one Democrat. Part of the strategy, Thompson explained, is to garner a majority (“the 51%”) to support an issue; in Arkansas, an issue needs 75 percent approval from the House and Senate to spend federal funding. Examples of building support include the expansion of children’s health insurance under the state’s Children’s Health Insurance Program and the use of Affordable Care Act money to develop an expansion strategy for Medicare, both of which happened under Republican leadership.

Thompson spoke about how Arkansas took on the obesity epidemic. The work began in 2003 by measuring the body mass index of children in every school. The results were sent home in a health report that explained the risks to families. The risks were not evenly distributed, but were notably concentrated in lower-income communities and communities of color. The difference was more apparent by looking more closely at race and gender, with Hispanic females having the highest risk for obesity followed by African American females.

Thompson worked with Angela Glover Blackwell, founder and president of PolicyLink, an equity and advocacy organization. Finding common ground was key to achieving the “51 percent.” In the case of childhood obesity in Arkansas, there were higher rates of obesity among poor white children than poor black children, but that was not meant to undermine the disparity. He said investments can be differentiated to enhance the unique

needs of poor communities of color, but it is most important to get to a place where the investment is available to make this change happen.

Thompson suggested ways to gain support for policies when there might not be initial buy-in. He asked one governor about his priorities, and the answer was the budget. Thompson thus considered how a health issue like childhood obesity affects the budget and framed his argument around cost savings, particularly for state and public school employees who had the largest insurance plan in the state. The data showed health care costs were higher for those who were obese, and addressing childhood obesity was one of the best ways to change the trends and reduce long-term spending. He said that he did not need to use the language of childhood obesity, health equity, or disparity, but instead needed to bring people together to start the conversation.

In closing, Thompson said, “As a strategist, as a tactician, I probably spent 25 percent of my time looking at the data and thinking about the policies. I probably spent 25 percent of my time trying to get the right people around the table. I spend about 45 percent of my time just on translation. People with the same issue but different language need to get to the same place.”

This page intentionally left blank.