9

Developing a Culture of Health Care Providers as Interveners

In the workshop’s final session, three speakers gave short presentations before Stephen Hargarten moderated an open question-and-answer session. The three speakers were Jay Bhatt, a senior vice president and the chief medical officer at the American Hospital Association (AHA), the president of the Health Research Education Trust, a practicing internal medicine physician at the Erie Family Health Center (Chicago), and a faculty member at both the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and the University of Michigan Medical School; Deborah Kuhls, a professor of surgery, trauma, and critical care and the program director of the surgical critical care fellowship program at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, School of Medicine, and the chair of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma Injury Prevention and Control; and Shannon Cosgrove, the director of health policy at Cure Violence.

HOSPITALS AGAINST VIOLENCE INITIATIVE

Bhatt began his presentation with a story—one that he said crystallized for him the importance of preventing firearm violence—about a 17-year-old boy shot dead while walking home from school one winter evening. The boy had no gang affiliations and was struck by a stray bullet fired during a fight between two rival gangs. The perpetrator, his tough guy façade gone, sits home afterward, alone, afraid, and in pain. The boy’s family, meanwhile, deals with an unfathomable grief and medical bills from their son’s treatment. Dad has to take a second job to pay those bills and spends little time at home, while the victim’s mom, once adherent to her blood pressure

medication, can no longer afford the cost of the drugs and is too paralyzed with grief and depression to care much about her own health. The victim’s sister, once an honor student, is failing her classes and may not graduate to the next grade. Six months after the boy’s death, the family wonders how long it will take for them to feel whole again.

This story, played out across the nation in different ways, encapsulates the message repeated throughout the workshop, Bhatt said—that there is a gap in longitudinal support and that interventions can help not only individuals, but their families as well. Given the urgency of addressing this problem, he said, the challenge is not just developing new interventions, but identifying steps that can be taken today to advance the work of firearm injury prevention.

Bhatt said the goal of AHA’s Hospitals Against Violence (HAV) initiative is to do just that: to share leading practices and examples across the field, with a particular emphasis on youth violence prevention, workplace violence prevention, and combatting human trafficking. AHA has developed a library of resources, interventions, and case studies, but it is the peer community sharing that will amplify this initiative, he said. Toward that end, AHA launched the first national day of awareness, called #HAVHope, in June 2017. #HAVHope is a social and digital media campaign that brings together hospitals and health systems around the country to share their stories and their collective efforts. In March, the HAV initiative hosted a national convening of human trafficking experts to discuss health system interventions to address this public health crisis and to continue to advise and inform programs and educational offerings. Additionally, HAV and AHA’s Coding Clinic, joined by experts from Catholic Health Initiatives and the Massachusetts General Hospital’s Human Trafficking Initiative and Freedom Clinic, worked to develop International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10) codes to identify human trafficking. Effective in fiscal year 2019, unique ICD-10-Clinical Modification (CM) codes are available for data collection on adult or child forced labor or sexual exploitation, either confirmed or suspected.1 These efforts will assist in identifying victims and improving the health systems that serve these patients and the community.

In thinking about the role that hospitals and health systems play in violence prevention, Bhatt said, it is important to consider that they serve as anchors for communities that can think about broader upstream issues, provide leadership and partner with governance, and take a community health needs approach. AHA created a community health needs assessment

___________________

1 See https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm.htm (accessed December 27, 2018) for more information about the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) codes.

finder, a dynamic Web tool that allows hospitals and health systems to come together on shared community health needs, including violence prevention, Bhatt said. Because hospitals and health systems are large employers—sometimes a community’s largest—they can serve as drivers of opportunity to create community partnerships and a community-based research agenda that promotes trauma-informed, evidence-based prevention programs.

To illustrate some of the ways in which hospitals and health systems can drive violence prevention efforts, Bhatt discussed some case studies. One is the Detroit Medical Center’s Detroit Life Is Valuable Everyday (DLIVE), which was created to address the fact that homicide is the leading cause of death for Detroit residents ages 15 to 34 and that the rate of violent injury recurrence at the city’s trauma centers is as high as 30 to 45 percent. By treating violence as a chronic disease, DLIVE has reduced the violent injury recurrence rate to zero among the 70 participants who have gone through the program in the past 18 months. In addition, the 80 percent of participants who had not finished school are now enrolled in education programs or have jobs.

In Chicago a new program, called Chicago HEAL, has brought together health care and legislative leaders to identify actionable and quantifiable areas related to the issue of firearm injury prevention and research. Some hospitals are addressing issues of jobs employment, while others are working on trauma-informed care training for the communities they serve. Collectively, Bhatt said, these hospitals are pooling resources and lessons to address gun violence in Chicago.

One issue that confounds violence prevention efforts is that a victim may get treated at a hospital outside of their primary care team’s network, and so the care team has no idea that their patient was injured. Electronic admission discharge transfer information is one technology that may be useful in addressing this problem, Bhatt said. Furthermore, predictive models and the use of clinical decision support can help engage clinicians inquire and potentially take action to prevent and reduce firearm injury.

CONSENSUS-BASED FIREARM INJURY PREVENTION STRATEGY

Across the United States, more than 500 trauma centers, verified by the American College of Surgeons, stand ready to treat the most seriously injured patients. Kuhls said all verified trauma centers are required to keep a trauma database of everyone who is admitted and these databases contain a wealth of information, largely on injuries and outcomes. Given that situation, Kuhls recommended that hospital-based violence intervention programs (HVIPs) should explore using this database as a repository for their data, given that it represents a well-developed, existing infrastructure.

Other requirements for trauma centers include that they implement

evidence-based injury prevention programs that address the main causes of injury-related death in the area they serve and that they hire an injury prevention specialist. Kuhls said the American College of Surgeons and other organizations offer an education and certification program for injury prevention specialists who come from a variety of backgrounds. One area in which many trauma centers could improve, she said, would be to get a better understanding of the mechanisms of injury for those individuals who never make it to the hospital because they go directly to the coroner and to include this information in their injury prevention plans.

Today, the American College of Surgeons, through its Committee on Trauma, is taking a public health approach to address the public health crisis of firearm violence. Given how controversial and divisive the topic of firearms can be, the organization first surveyed its leaders in trauma surgery to find out their opinions on firearm injury prevention and advocacy; a survey of all 80,000 American College of Surgeons members was just completed and its results were being awaited at the time of the workshop. The initial survey, which received more than a 90 percent response rate, revealed that:

- trauma surgeons felt that violence is the root cause and is a major problem in the United States,

- reducing firearm injuries and deaths should be a top priority for the American College of Surgeons,

- health care professionals should be allowed to talk with their patients about how to prevent firearm injuries,

- the federal government should fund research on firearm violence, and

- the trauma community should partner with mental health to address the mental health components of firearm injuries and death.

Based on the survey of trauma surgeon leaders, the Committee on Trauma developed a nine-part strategy which included signing a memorandum of understanding with the National Network of HVIPs, creating a primer on HVIPs, spreading the word about the efficacy of HVIPs, and having trauma surgeons commit to talking to parents who own guns about how to keep their families and friends safe. To help with this last task, the Committee on Trauma published a brochure on gun safety and health that stresses being proactive about protecting those in the home by safely storing guns and ammunition. Kuhls and her colleagues are now piloting a tablet-based program on gun safety in the home targeted at pediatrics patients and their parents or guardians, and while the organization does not currently give away safety devices, it is exploring that possibility. Kuhls added that the organization is going to take its plan to other health care organizations to see if they would like to join this effort.

An important piece of this initiative is to build a public consensus to reduce firearm death and injury by working together, understanding and addressing the underlying cause of violence, and making firearm ownership as safe as possible. The American College of Surgeons has adopted the motto “Freedom with Responsibility” and issued its consensus strategy for preventing injury, death, and disability from firearm violence (Stewart et al., 2018). The American College of Surgeons is also actively engaging a group of surgeons who are avid, vocal firearm owners. This group provided input that guided the development of this brochure and then endorsed it. “We find that engaging them really helps to make us successful,” Kuhls said.

Going forward, the Committee on Trauma is developing a recommended, comprehensive research agenda, she said, although it is taking its time as this is something new for the organization.

THE CURE VIOLENCE APPROACH

To begin the final presentation of the day, Cosgrove said she wanted to add one datapoint to the discussion, one that was first identified in a 1985 report from then Secretary of Health and Human Services Margaret Heckler (Heckler, 1985): when looking at the largest health disparities between the Black and white population in the United States, the disparity in homicide rate was the worst of all, at 400 percent higher for Black Americans than white Americans. When health disparities were examined again in 2013, that disparity had risen to 470 percent higher, while the gap between the Black population and white population on most other health issues had decreased. The reason that she cited these figures, Cosgrove said, was that the health system has not invested as much in reducing disparities in homicides as it has in other areas, such as cancer and diabetes. That lack of investment and lack of a comprehensive health system has allowed the epidemic to spread, she said.

With that as background, Cosgrove explained what Cure Violence does as an organization. Founded in 1999, Cure Violence was intended to replicate the World Health Organization’s three-pronged approach to epidemic control, which involves interrupting transmission, working with those at highest risk to change behaviors, and changing community norms. Cure Violence founder Gary Slutkin, who previously served as an epidemiologist with the World Health Organization, conducted a pilot program in Chicago using this three-pronged approach. Specifically, the three prongs were (1) interrupting transmission, which involved preventing retaliations, mediating conflicts, and keeping conflicts cool; (2) reducing the highest-risk behaviors, which entailed assessing who is at highest risk, changing their behaviors, and providing appropriate treatment; and (3) changing commu-

nity norms, which was focused on responding to shootings, organizing the community to take action, and spreading positive norms.

When the Cure Violence model was first implemented in Chicago, it resulted in a 67 percent reduction in shootings. The program expanded and was then replicated in Baltimore, where it also resulted in large reductions in shootings and killings. Since then, the Cure Violence program has been implemented in more than 100 communities across the United States and 20 additional communities around the globe. Cure Violence’s main focus is working with credible messengers, that is, individuals who have access and credibility among those at highest risk for violent behavior. The program hires these individuals and trains them to support fellow community members who are at the highest risk of becoming involved in violence.

According to independent evaluations, Cure Violence has resulted in reductions as high as a 73 percent drop in shootings in communities in Chicago, 43 percent in communities in Baltimore, and 63 percent in communities in New York, which had just experienced a full weekend without a shooting just prior to the workshop. “We are seeing these numbers translate across the world, in places like San Pedro Sula, which was previously the most violent place in the entire world,” Cosgrove said. The most recent evaluation in New York City also revealed an increased level of trust between the police and the community and indicated that the positive impact of the program had spread into surrounding neighborhoods.

Norms overall are changing, too, Cosgrove said. “We are seeing tremendous reductions in one’s likelihood of being involved in violence,” she explained. The most recent evaluation in New York found that the more times someone was interacting with a credible messenger or seeing the program messages overall, the lower the likelihood that person would be involved in violence or even think about being violent in the future. Perhaps the most striking results have been in the city’s Queensbridge Houses, the largest public housing development in the country comprising 96 buildings spread across 6 blocks, where there have been no shootings or homicides for more than 1,000 days.

Cure Violence is not the only successful program for reducing gun violence using health approaches, Cosgrove said, but unfortunately these different programs are not working together to figure out how to integrate their work and create a comprehensive system for violence prevention. To address that shortcoming, Cure Violence started the Movement towards Violence as a Health Issue, which has five goals:

- Develop common understanding and language to convey the message that violence is a health issue.

- Increase policies, including sustainable funding, to support health approaches to violence prevention.

- Increase the use of health and community systems to prevent violence.

- Advance racial and health equity.

- Develop multi-sector partnerships and coalitions.

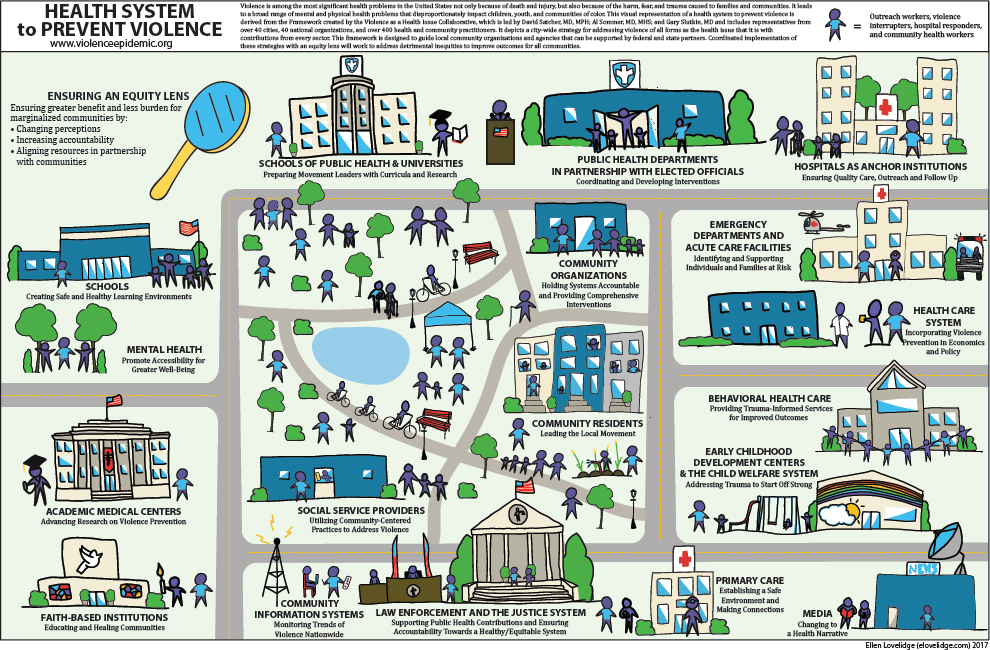

The movement has support from Congressional officials, the leaders of health care agencies, public health institutions, and more. With more than 600 members and leadership from Slutkin; David Satcher, the former U.S. Surgeon General; and Alfred Sommer, the former dean of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, there is momentum building toward seeing violence as a health crisis, believing that health leaders need to take on this charge, and understanding that interventions exist that have proved effective. The movement has developed multiple briefing documents and toolkits and also produced a framework for the health system to prevent violence (see Figure 9-1), which includes best practices across the United States to prevent all forms of violence. The framework lays out an integrated approach across all sectors highlighting the need for shared data and protocols to prevent violence and to heal individuals affected by violence—“not just healing within the hospital walls or reducing risk immediately,” Cosgrove said, “but ensuring people have the chance to heal within their community to be free from violence.”

This initiative is seeing success, particularly in terms of growth in investments in violence prevention, Cosgrove said. Much of the new money has come from the Department of Justice, and Cosgrove questioned why the nation’s health agencies are not funding these efforts at levels in line with the need. Working with Representative Mike Quigley (D-IL-05), who represents part of Chicago, Cosgrove and her colleagues designed H.R.2757, the Public Health Violence Prevention Act, which would amend the Public Service Health Act to establish a National Center for Violence Prevention and provide $1 billion to be invested in implementing health approaches in communities across the nation. Cosgrove explained that the hope is that this bill will be reintroduced after January 1, 2019. Maryland, meanwhile, passed the Public Safety and Violence Prevention Act of 2018. Cosgrove explained that this act incorporates much of what was in the federal bill and allocates $5 million to public health departments, hospitals, government agencies, and community-based organizations to integrate evidence-based violence prevention health approaches statewide.

DISCUSSION

Stephen Hargarten opened the discussion period by asking the panelists to discuss the cultural challenges that health care systems and various organizations working in communities face in their efforts to be actively

SOURCES: Figure presented by Shannon Cosgrove at the workshop on Health Systems Interventions to Prevent Firearm Injuries and Death on October 18, 2018. Created by Ellen Lovelidge for Cure Violence (Cure Violence, 2017).

engaged in firearm violence research and intervention. Bhatt replied that health care systems have been in a sick care system and only recently have had incentives and opportunities to effectively work upstream. Part of the challenge, he said, is finding the resources to engage more in the community and to address upstream factors that lead to violence, particularly in rural communities that are being affected by reduction of access points.

At the same time, he said, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) created opportunities for value-based care that create a potential channel for investing in violence prevention. In his opinion, Hargarten said, delivery systems need help reorganizing their resources and their approach to violence prevention so that it includes training staff to ask the right questions and use the electronic health record to document cases involving violence. Bhatt said that the American Hospital Association (AHA) is now helping hospitals and health systems have conversations with community partners to help rebuild trust within the community.

Kuhls said that she sees trauma centers as a model that could be expanded nationwide with additional funding, noting that trauma centers exist nationwide and that they are required to partner with community organizations in injury prevention. One of the challenges is that there are what Kuhls called “trauma center deserts” throughout the country, but she noted that there are other health systems, such as the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and active military installations with medical facilities, that share many of the same firearm injury and prevention challenges in their patient populations and could be important partners. Cosgrove added that an important and needed culture change would be to treat violence as a health issue rather than solely a law enforcement issue. In her opinion, she said, there are not enough health leaders promulgating that message.

Bhatt commented that there are a number of challenges to implementing and scaling effectively that stem from the importance of contextual differences at sites of implementation. Kuhls pointed to the shortage of sustainable funding to do implementation science and the importance of engaging those who have been the victims of violence when preparing to implement a program in a new region. Both funding that is not sustained and a lack of consistent leadership advocating for funding affects community trust negatively, she said. When a grant vanishes, those trusted members of the intervention team lose their jobs and the community loses a valuable resource.

Bhatt agreed that the community needs to advocate for increased and sustained funding, but it also needs to be innovative in how it uses the resources it has. For example, firearm screening could be bundled with lead paint screening, given that both can have long-term effects on children. Technology such as telehealth can also help leverage limited resources

and limited personnel, particularly in doing longitudinal work focused on violence.

In response to a question about the kinds of levers health systems could use to address gun violence, Bhatt said that there are workforce models that would help deliver desired outcomes, including data-driven interventions in the emergency department for behavioral therapy interventions to be delivered for every victim of violence. Cosgrove said that the ACA’s required community health needs assessments could provide such a lever, but a recent review by Kyle Fischer and colleagues of hospital needs assessments in the 20 most violent U.S. cities found that although 74 percent of those assessments included violence or assault, those were just mentions or a single data point (Fischer et al., 2018). In fact, in only 32 percent of those cities had health systems integrated those health assessments into their plans to spend community benefit dollars, and most of those health systems already had HVIPs. The challenge, Cosgrove said, is holding health systems accountable for using the community health needs assessments to implement violence intervention programs. She cited Louisville, Kentucky, as an example of a city doing just that in coordination with their health department.

Bhatt said the nearly 5,000 members of AHA are trying to figure out ways to address the social determinants of health. What appears to work well, he said, is applying what hospitals and health systems do well in terms of systematic quality improvement to the social determinants of health. He noted, too, that all 50 state hospital associations have signed onto AHA’s equity of care campaign, which has nearly 1,700 hospitals taking targeted steps to reduce inequities. “The journey to zero is possible there, and it is something that we can continue working toward,” Bhatt said, referring to the Institute of Medicine report To Err Is Human and its call to reduce hospital-based errors to zero (IOM, 2000).

An unidentified participant asked if the National Academies would consider holding a workshop that would focus on translating the VHA’s model for trauma treatment into the civilian sector. Hargarten supported that idea. He then noted that a city can request the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to investigate the causes of the violence killing people in its community. “That is a little-known public health assessment that also may provide information to health care systems about what they can additionally do to address an outbreak in their city,” Hargarten said.

A workshop participant asked Cosgrove how she responds to people who do not believe violence to be a health issue. She replied that she starts off by listing the general causes of death, which alerts people that violence is high on that list. She then talks about health care expenditures and loss of life, and those point to the same issue. She also addresses how violence and exposure to violence affects health and discusses the definition of health as being not only the absence of disease or infirmity but the complete state of

physical, mental, and social well-being. Health is impossible when violence is present; therefore it is a health issue, Cosgrove added.

Joseph Richardson from the Capital Region Violence Intervention Program, an HVIP that has been running for more than 1 year and has served 116 participants, none of whom have returned to the emergency department, asked about the role that involvement with the criminal justice system plays as a risk factor for repeat violent injury and how to ameliorate the effects of incarceration on the risk of either engaging in or being a victim of violence. Bhatt replied that the criminal justice system has to be a critically important part of this discussion. He noted that the Data-Driven Justice Initiative, which includes 70 municipalities, has operationalized a data-sharing system that can provide data to drive particular interventions.

As a final comment, Hargarten clarified that the Dickey amendment prohibited CDC from using funds for advocacy purposes, not for firearm-related research. That was never prohibited, he said. However, the amendment did dampen funding streams by politicizing the issue. Congress can approve funds for research, but it has chosen not to, an important point from the perspective of CDC, which has funded firearm-related research to the extent that it can.

This page intentionally left blank.