4

Identifying Individuals at Higher Risk for Firearm Violence

The workshop’s second panel featured three short presentations on approaches for identifying those individuals most at risk of experiencing firearm violence. The three speakers were Megan H. Bair-Merritt, the executive director of the Center for the Urban Child and Healthy Family, an associate professor of pediatrics and the associate division chief of general pediatrics at Boston Medical Center; Christopher Barsotti, the chief executive officer of the American Foundation for Firearm Injury Reduction in Medicine (AFFIRM) and the chair of the Trauma and Injury Prevention Section of the American College of Emergency Physicians; and David C. Grossman, the senior associate medical director for market strategy and public policy and a senior investigator at Kaiser Permanente’s KPWA Health Research Institute. An open discussion moderated by Therese Richmond followed the three presentations.

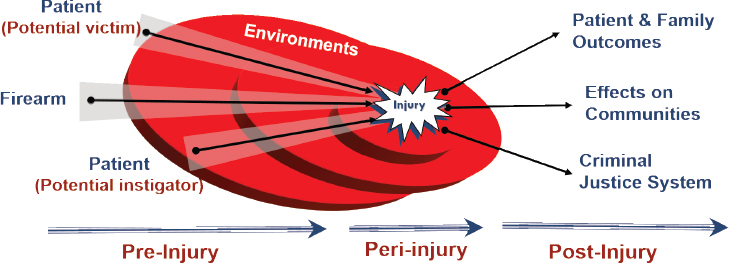

Before introducing the first speaker, Richmond presented a visual representation of the Haddon Matrix (Runyan, 1998; Short, 1999), a framework for preventing injuries that looks at factors related to personal, vector, and environmental attributes that can contribute to injury (see Figure 4-1). This illustration, she said, indicates that three things—a potential victim, a firearm, and a potential instigator—have to come together for a firearm injury or death to occur. It also underlines the importance of looking for environmental factors that might be modifiable and offer opportunities for intervention. “As we think about keeping this injury event from happening,” Richmond said, “we can think about the three paths into an injury. We can think about the environment in which the injury occurs, and we can think about it in terms of both risk identification or identifying higher-risk

SOURCE: As presented by Therese Richmond at the workshop on Health Systems Interventions to Prevent Firearm Injuries and Death on October 17, 2018.

situations or patients, and also as protective factors, because everybody has both. If we have lots of protective factors, we may change our risk stratification of individual patients.”

IDENTIFYING SURVIVORS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE WHO ARE AT HIGH RISK FOR FIREARM-RELATED VIOLENCE

Bair-Merritt said that within the larger field of domestic violence, the research on domestic violence and firearms has, for the most part, taken place separately from research on identifying domestic violence and health system response. What is known, she said, is that 44 percent of female homicide victims are killed by an intimate partner and half of those incidents involved a firearm (Petrosky et al., 2017). She said that having a firearm in the home increases the odds of a survivor of domestic violence being shot by a factor of seven. Other important risk factors include women’s assessment of their own risk and worries about escalating violence and a prior history of choking and strangulation. “This is predictive of future death and morbidity,” Bair-Merritt said, “and so this is something we have to really listen and pay attention to.” She also commented that most of the literature on identifying survivors of domestic violence who may be at risk comes from the Danger Assessment instrument developed by Jacquelyn Campbell at Johns Hopkins University (Campbell et al., 2009; Messing et al., 2017; Snider et al., 2009), which has mostly been used by law enforcement to assess future risk. The original instrument has been scaled down to a five-item instrument for use in an emergency setting.

Bair-Merritt remarked that when she first started working on identifying intimate partner violence (IPV) in a health care setting, the general

response was that it was a social work problem, not a medicine problem. Today, screening for IPV has become a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) level B recommendation, but the focus is on identifying survivors, and the response tends to be educational. “We have not done good work in thinking about risk stratification and thinking about different interventions based on the situation that the survivor is presenting with,” Bair-Merritt said. “So how do we partner with law enforcement and our domestic violence advocates to have a better response?” In her opinion, she said, speaking as a pediatrician, she believes that health care needs to think more about what its response should be when children are in homes with IPV, given the future risk for violence those children may face as a result of IPV exposure.

APPLYING A MEDICAL MODEL OF DISEASE TO IDENTIFY THOSE AT RISK OF FIREARM VIOLENCE

Barsotti said that his interest in identifying those at risk of firearm violence arose from his experience working at a rural level 3 trauma center, where he and his partners had intervened in cases where they thought there was a chance of mass violence, suicide, or IPV. “We keep getting these cases, and we need guidance as community practice physicians,” he said, “so I decided I would try to find out what could be done to advise us in practice to identify and treat high-risk individuals, and I realized, in fact, that there is no guidance.” Getting such guidance, he concluded, would require research, but there was little research money available for this type of work. Barsotti’s response was to join forces with Megan Ranney and form AFFIRM, a nonprofit organization that aggregates money from private-sector sources and uses those funds to support research by medical societies and medical professionals.

He said that his training in emergency medicine on gun violence called for treating the victim, period. In the same vein, data collection was mostly about measuring the first-year costs associated with gunshot wounds and emergency department visits, with no reporting about the collateral, long-term costs that can result from gunshot wounds, such as the need for lifetime colostomy care or dealing with a spinal cord injury for the following decades. Little if any attention was paid to secondary victims, including those who witnessed violence and even those who treated the victims of firearm violence. “After shootings, I take care of my colleagues,” Barsotti said. “I take care of nurses and paramedics traumatized by treating victims of gun violence.”

In his view, he said, the opportunity for primary prevention is always present. “When we apply the medical model of disease to this problem, I can look at it like any other health problem that has a natural history because I am seeing these patients when they first express the risk factors or

when risk factors escalate, and if we are able to intervene effectively, then we can prevent the shootings.” He said that it is his hope that, moving forward, research can define the points of contact for physicians working in clinics and emergency departments so they can identify those individuals who have a latent risk and are having their first expression of that risk. The goal then would be to prevent that risk from escalating and, if that does not work and a shooting occurs, to have an opportunity to mitigate the secondary effects of gun violence to prevent further shootings.

FACTORS TO CONSIDER WHEN THINKING ABOUT IDENTIFYING RISK OF FIREARM VIOLENCE

Grossman made six points relevant to identifying those at risk of firearm violence. The first was that it is imperative to understand how to intervene with gun injury and death at the right time, in the right place, and with the right people. “Timing and place are critically important as we think about how to identify risk and mitigation opportunities,” Grossman said. His second point was that firearms are likely to be a permanent part of the U.S. societal environment, which has the effect of fixing one variable in the Haddon Matrix that is foundational to the science of injury control. Third, firearm injury is still a relatively rare occurrence in absolute terms, which means that identifying those at risk is a little like finding a needle in a haystack. “It makes discrimination in the science of risk prediction more complicated than perhaps for more common causes of mortality,” he said.

Grossman’s fourth point was that targeted interventions make sense to the extent that there is a good understanding of who should receive an intervention, and his fifth point was that the assessment and intervention must be easy for clinicians to enact. His sixth and final point was that health systems need to use state-of-the-art risk prediction methodology just as they do for predicting the risk of cardiovascular events, osteoporosis, breast cancer, and other serious conditions. “These are tools that have been developed to address a wide variety of clinical conditions and that have been carefully honed to understand both our ability to accurately predict risk,” Grossman said, “and that, at any time you are doing risk prediction and interventions, there is always potential for adverse outcomes and adverse effects. To the extent that we can improve the accuracy and the discrimination of those tools, we will be much better off.” He acknowledged that, given the current funding environment, developing such tools for predicting risk of firearm violence will be difficult, but he said that he believes there is ongoing research on mental health services that could be extended to develop multivariate modeling for predicting who is at risk for a firearm injury.

DISCUSSION

Richmond started the discussion by asking the panelists for ideas on how to identify the right person at the right time and place and with the right intervention. Barsotti said that doing so will need to start with identifying when it is relevant for practitioners to evaluate the risk of firearm violence, which will require identifying those patient contexts and presentations for which it is relevant to inquire about a patient’s firearm access. He added, though, that he still does not know what the right intervention is. He also said that there is an opportunity to make a better case for funding research. “When we have a more robust and comprehensive view of the problem, we can calculate its burden and costs better in order to make a case for better case for funding,” he said.

Grossman agreed that clinicians do not know what to do if they do identify a patient at risk of firearm violence. One reason is that there is a lack of strong evidence to support possible interventions, so clinicians, to the extent they are guided by and trust evidence as a basis for practice, do not have evidence-based guidance. Another reason is that even in the best practices, more work is needed on how to best communicate risk to patients and families. Bair-Merritt remarked that gun violence, as a multidisciplinary problem, will require health systems to be humble and involve various partners from the community—from mental health, for instance, and from law enforcement when it comes to intervening. “Whatever that intervention ends up being, I do not believe health care can do it by itself,” she said.

Richmond asked Bair-Merritt if health care systems and providers attend equally to identifying potential victims and potential perpetrators of firearm violence, to which she said no. “If you look at all of the work on intimate partner violence screening, there is much more for survivors of violence than there is for perpetrators of violence,” Bair-Merritt said. “There are a few people who are thinking carefully about how we assess risk for perpetrating intimate partner violence.” She said that to her it is important when thinking about firearm injury to treat it as more of a syndrome, that is, a collection of symptoms associated in this case with a possible outcome, rather than a disease where the underlying cause is known. “The situation of an adolescent carrying a gun to school is so vastly different from the issue of a survivor of adult partner violence,” she said. This indicates that the right intervention will have to be situation-specific.

Barsotti agreed, noting that the diagnostic questions a clinician asks in a mental health assessment depend on the context and collateral history. He said that he would like to have a specifically structured interview about firearm risk given to patients who present with any type of firearm risk, such as a child who presents with certain kinds of accidental injuries, or who appear to be at risk of harming themselves or others. Noting that

elaborate and cumbersome risk assessment tools are already available for firearm injury risk, he asked if it might be possible to create something simple that could start the screening process and perhaps classify someone as low, moderate, or high risk. Such an instrument, he said, would then allow for further research to parse those with moderate or high risk into smaller categories with specific interventions indicated.

With regard to what health systems need to put in place for providers to recognize the need and then screen for those at higher risk, Grossman said a good place to start would be for health systems to develop clinical guidelines that are based on evidence, continually revised when new evidence becomes available, and tailored to the site of care, such as the emergency department or the primary care office. Then these procedures will need to be embedded in the workflow in a way that fits the clinician’s practice. As an example, he recounted how clinicians in his health system were uncomfortable when asked to implement a dental fluoride varnish program. Once the program was sold as something that could be implemented in the same way that childhood immunizations were implemented, the physicians got on board. It will also be important, he said, to help providers be confident in their ability to screen and to talk about firearm violence with their patients and to have a system designed to make it easy for clinicians to hand off their patient for the intervention, Grossman said.

Bair-Merritt agreed that there is a need for clinicians to feel confident in their ability to assess risk, given that most are not trained to do so, and also to feel confident that the interventions will be efficacious. One concern of hers, she said, is that the hard conversations around firearm violence in families will contribute to physician burnout. “I think for our system to change, we have to build supports for our workforce as well,” she said.

Any progress, Barsotti said, will depend on building a new paradigm for how health systems think about firearm violence, and he noted the health system actually has experience implementing such a paradigm. Forty years ago, he said, physicians thought of child abuse in terms of beat-up kids and bad parents. “Then, over time,” he said, “we crafted a child abuse paradigm that enabled elaborate and layered interventions, and as a result, we have seen a decrease in severe child maltreatment. We are at that point right now with gun violence. We have to create a new paradigm on which to build and wrap our brains around this.” Grossman agreed and said that this new paradigm is being built partly through advances in behavioral medicine that are working for tobacco and alcohol issues and lead to behavior change. “Clinicians are starting to wake up to the idea that not all interventions involve a needle or a scope, that talking therapy does work and motivational interviewing does work,” he said.

Richmond then asked if, to get the biggest bang for the buck, risk assessment should focus on primary care or if it should cross all aspects of

the health care system. Barsotti replied that, as with child abuse, everyone who encounters a person at risk or suspects a person is at risk should refer that individual for follow-up, and there should be social constructs and policies developed to help that process. For example, he said, his home state of Vermont has operationalized extreme risk protection orders.

Bair-Merritt commented on the challenge of convincing every member of the health care team that they have to participate in such efforts, noting that there is still resistance when it comes to screening for domestic violence. “There are some late adopters who are coming around, and there are some people who will never think that this is part of what medicine should be doing,” she said. She added that a key finding from a systematic review of IPV interventions in clinical settings was that the most effective interventions were ones that involved everybody, from the front desk person checking the patient in through the nurse, the medical assistant, and the clinician (Trabold et al., 2018). “It has to be a multilayered system that everybody owns a part of,” she said.

To Grossman creating clinical guidelines as the key, since guidelines are the foundation for professional behavior. In an integrated health system, culture means everything, he said, and it is important to have a clinical culture that understands that it has certain professional norms, responsibilities, and accountabilities that are developed with broad input and evidence. At his institution, for example, a behavioral health and integration initiative has seen the use of the Patient Health Questionnaire increase significantly through a regimented process of developing and promulgating evidence-based clinical guidelines and providing feedback to those staff members who were slow to get onboard with this initiative. Peer pressure, Grossman added, is a powerful incentive for change.

Bair-Merritt said that she is concerned that asking about domestic violence will become a checklist item rather than a true conversation. On the other hand, Gregory Simon from Kaiser Permanente Washington State said that simple multiple choice, yes/no questions administered on clipboards or in waiting room kiosks by medical assistants with not much more than high school training are quite accurate at identifying people who are at high risk for self-directed violence or death by suicide. “Since the health care system has a proud tradition of squashing the good enough for lack of the perfect, I would say let’s not do that here,” he said.

When asked about how to create a culture and environment where productive conversations can occur, Grossman answered that the challenge is to provide a process that allows physicians to see that such conversations are valuable to their patients. Such intrinsic incentives—as opposed to paying for performance—are hard to operationalize in a prevention setting because the clinician is not likely to see what does not happen. “It is much easier to be gratified by a patient that heals in the trauma center and see-

ing the importance of the work that you did there,” he said. One solution would be to study the effects of an intervention, use the results to estimate how many lives are saved, and point to those results as a means of making providers proud of their efforts to do the right thing by their patients. Barsotti suggested that it could be useful to publish case-based narratives that describe opportunities of how and where clinicians can intervene.

Richmond asked the panelists about the possibility of identifying and supporting protective factors in addition to looking at risk. Barsotti and Grossman both said that there is little evidence concerning protective factors for firearm violence. Bair-Merritt said that there is some evidence about individual-level, neighborhood-level, and community-level factors that are protective when people are in domestic violence relationships, but there is a need for more robust interventions to nurture those protective factors. Barsotti said that in communities where firearm ownership is the norm, it will be important to engage firearm owners in efforts to identify those behaviors that are protective and which ones are not. In his experience working in a rural environment, he said, screening patients for firearm ownership has never turned into a political discussion. Moreover, every time there was somebody in the community who was perceived to be at risk, the community or family acted to secure the lethal means. “It is never a problem, because they recognize the risk, and are all on board,” Barsotti said.

When asked to identify important research questions to address that would enable health systems to accurately identify higher-risk individuals, Grossman said it would be important and helpful to develop multivariate models, particularly around the interaction of alcohol and mental health, in order to better understand who is at higher risk for gun violence and to identify the key variables driving gun violence. “We have become good at predicting univariate risk, but not so great on multivariate risk,” he said.

Barsotti said he would propose studying the trajectory of risk in order to identify transition points where low risk becomes moderate or high risk. Bair-Merritt said it would be important to understand the benefits and risk of screening in a health system. For example, if screening identifies a family situation where there is a risk of firearm violence, it could trigger a call to child protective services and trauma for the family. “We think screening and identification are great,” she said, “but we need to think about potential risks for our patients as well.” Grossman agreed with Bair-Merritt and noted that USPSTF routinely looks at harms associated with screening methods, treatments, and interventions.

George Isham asked the panelists if there are certain populations that are more at risk of firearm violence and if health systems should develop a priority list for screening. Bair-Merritt and Grossman agreed that prioritization would be a good approach, given that firearm violence is still a relatively rare event. Barsotti said that there is low-hanging fruit in each

domain of violence and after identifying the population at greatest risk within each group, health systems should roll out a program to capture the easiest, most readily identifiable populations. Richmond added that the populations most at risk will vary depending on the health system and the communities it serves.

Bechara Choucair asked if there is a role for publicly available data from outside the electronic health record (EHR) that would be useful for creating predictive models. He said that Kaiser has treated more than 11,000 gunshot victims in its emergency departments in 2016 and 2017. “Can we imagine a day,” he asked, “where we have an algorithm that would tell me here are the 11,000 people who are likely going to be coming to our emergency department dealing with gunshot wounds, and let us think about the right interventions to be proactive with those 11,000 members so we can get to them before they end up being victims of gun violence in our emergency department?” Grossman agreed that the field needs to be nimbler in its use of external data, although, he pointed out, linking and integrating datasets is challenging. His research institute at Kaiser Permanente, for example, routinely links enrollment data to death certificates in order to understand what is going on its member population. Washington State’s new Accountable Communities of Health process, which is empowering and funding clusters of counties to be accountable for their own epidemiology and planned interventions for their own regions, is a promising approach to community-focused interventions, he said. Barsotti said that many victims of gun violence belong to a network of other high-risk individuals, and social media may provide an opportunity to identify those network members.

An unidentified workshop participant noted there is a new documentary film—Portraits of Professional Caregivers: Their Passion, Their Pain1—that illustrates the effects of exposure to gun violence victims on their caregivers and providers. This film, the participant said, prompted the Philadelphia city council to hold hearings in December 2018 on the issue of secondary trauma in professional caregivers and first responders.

Carnell Cooper said that when the University of Maryland started its hospital-based, violence prevention program two decades ago, the health system would see a few domestic violence patients. Then, about 8 years ago, the health system decided it needed a program aimed specifically at domestic violence, and it soon started getting about 100 referrals per year. Four years ago, the University of Maryland embedded a mandatory screen in its EHR—it had to be completed before the patient’s record could be closed—and that number jumped to 500 referrals per year. He then asked the panel whether they thought an EHR screening processes would be use-

___________________

1 See http://caregiversfilm.com (accessed October 30, 2018).

ful. Bair-Merritt said yes, but added that such a screen has to be accompanied by training for providers so that they know how to respond to this information. Cooper agreed but said he thought that having a specific group of providers trained as a response team would work best because some groups—he named trauma surgeons—are not going to want to respond.

Evelyn Tomaszewski from George Mason University suggested that clinicians or others with lived experiences might be the best counselors in a health system, an idea that Barsotti and Bair-Merritt agreed had value. Grossman said that the lived experience of the targeted population is also a critical factor in understanding what interventions might work. “We cannot test interventions without really fully engaging and involving the target population in that process,” he said. For example, he said, he and his colleagues conducted a randomized trial of gun safes in rural Alaska among the Alaska native population, and they spent time with that population trying to understand its behavior around guns as well as to understand what is socially acceptable around storage practice. “We tried to map that out ethnographically before we even began to think about implementing the trial,” he said.

As a final comment to close the discussion, Rebecca Cunningham from the University of Michigan reiterated an earlier message that different settings will require different solutions and that those solutions do not have to be physician-centric. “Physicians may be great at raising awareness,” she said, “but they do not necessarily [have to] be the answer for either the screening component or the intervention components.”