5

Developing Health System Interventions

Session 3 focused on interventions that health systems can adopt going forward. The two speakers in this session were Marian Betz, an associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and Megan Ranney, an associate professor of emergency medicine at Brown University and the chief research officer at the American Foundation for Firearm Injury Reduction in Medicine (AFFIRM). A question-and-answer session moderated by George Isham and an open discussion followed the two presentations.

DEVELOPING A FIREARM STORAGE DECISION AID TO ENHANCE COUNSELING ON ACCESS TO LETHAL MEANS

Betz began by acknowledging that she, like most every other health care provider, has complex views about firearms. On the one hand, she said, she works on the front lines as an emergency medicine specialist, and she is frustrated by the senseless injuries caused by firearms. At the same time, she is a proud Colorado native, and hunting is a part of the culture for many people, including her extended family, and responsible gun ownership is a way of life for many people. While she has lost friends and family members to suicide and has been left struggling with thinking about how she could have prevented those deaths, she has also had some of the most satisfying collaborations in her professional career working with firearm ranges, gun retailers, and firearm owners. “At the core of my work is something that may sound a little simplistic,” Betz said, “but it is important that we recognize that our views vary, but nobody wants to lose a family member or

friend. Nobody who owns a firearm is okay with a family member dying by suicide or a child dying by accident. We need to come back to recognizing that everybody wants their loved ones to stay safe.”

Betz said that of the 36,658 firearm-related deaths in 2016, 59 percent were suicides and that 50 percent of all suicides are by firearm (CDC, 2018). “This is why you cannot talk about reducing firearm deaths without talking about suicide, and you can’t talk about reducing suicide deaths without talking about firearms, because they are so closely linked in this country,” she said. Though most discussions about firearm violence center on homicides and mass shootings, which account for approximately 39 percent and 0.3 percent of firearm deaths, respectively, tackling the problem of suicide by firearm is equally important and will require different solutions than for homicides, she said (CDC, 2018). Being suicidal is not a terminal illness, and about 90 percent of people who survive an episode of having suicidal ideation or who attempt suicide do not later die by suicide (Owens et al., 2002). At the same time, she said, firearms have the highest case fatality rate of any method of suicide at 85–90 percent: higher than any other methods (Spicer and Miller, 2000). “Certainly, we should be talking to patients about making the environment safe in many ways, but firearms are the method where there is usually no second chance,” Betz said.

Another fact about suicides, she said, is that although suicide attempts often occur on a background of longstanding mental illness and other risk factors, the period of highest risk is often somewhat short. “The time point between deciding to take action and taking action can be in the range of minutes to hours,” she said, “and that’s why we think about trying to keep someone safe during this particularly high-risk period.” Betz added that people who live in homes with a firearm in them have higher odds of death by suicide. This is not because of differences in suicidal ideation or mental illness in gun owners versus non-gun owners, but rather because if a person can access a firearm at that moment of crisis, they are more likely to die. She added that there is some evidence that counseling the parents of adolescents at risk of suicide can lead parents to change how they store their firearms. This is called Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM), an intervention now recommended, especially in emergency departments and mental health settings in the context of suicide risk. Betz thinks of it as similar to appointing a designated driver when someone in a group is intoxicated or at risk of becoming intoxicated. In the context of suicide risk, she encourages people to either lock their firearms and put the key in a place where the person at risk will not have access to it or else to remove the firearms from the home and store them somewhere else, at least temporarily.

CALM alone is not a solution to the suicide problem, Betz said; instead it must be part of a comprehensive prevention approach that should address all types of upstream risk factors and that intervenes along a trajectory of

suicidal behavior. Given that emergency departments are a key site for care of patients at risk of suicide, emergency department staff need tools to enable them to do a better job of identifying those individuals and caring for them. Unfortunately, Betz noted, she and her colleagues have found that CALM is not used in a majority of instances when a patient was clearly at risk of suicide (Betz et al., 2016, 2018).

Among the barriers that inhibit discussing firearm access in the home are a lack of time, workflow issues, and the fact that some health care providers are unsure if they are allowed to ask about firearms. “The short answer is yes, it is okay to ask,” Betz said. However, although it is legal to ask, many practitioners do not know how to raise the question in a way that is nonjudgmental and will not offend the patients or family members. And even if they ask the question, physicians often do not know what to say if there are firearms in the home. Betz said that she had one colleague, for example, who asked her if a patient had to be hospitalized because of having some mild suicidal thoughts and owning a gun. The answer was no, but it was important to think about how to reduce access to that person’s firearms. “These are real questions from front line providers, because we were never trained in how to do this,” Betz said.

Provider training is important, she added, and so too is having interventions that are acceptable to patients and providers. Such interventions need to use respectful and neutral language because they are not intended to change somebody’s identity as a gun owner. “This is about helping them be safe and then encourage behavior change,” Betz said.

In her work, Betz said, she has been interested in the decision-making process around firearm storage, particularly when someone in the home is at risk of suicide. She and her colleagues decided to use the Ottawa Decision Support Framework (Murray et al., 2004), a three-step, evidence-based process for making health or social decisions that involves assessing what both the patient and provider need to make a decision; providing decision support in the form of counseling, tools, and coaching; and evaluating the decision-making process and outcomes. The basic idea behind the framework is that making a high-quality decision requires knowing the options and then making a decision in line with personal values that produces the desired outcomes.

In the case of firearm safety, Betz said, she and her colleagues want to know what people think about different firearm storage options and to provide them with options from which they can pick based on what is best for their particular situation. With support from the National Institute of Mental Health, her team has built a decision aid which they are now testing and will make available when they have completed testing, likely in spring 2019. This decision aid is not intended to replace discussion with a health care provider; rather, the patient (or concerned family or friends) can work

through it alone and then discuss it with a provider. The resulting Lock to Live decision tool is intended for adults with suicide risk, and Betz’s team is working with colleagues at the University of California, Los Angeles, to develop a version for adolescents.

Lock to Live has three preference questions, Betz said:

- How open are you to storing your firearms temporarily with someone else, away from your home?

- When looking for storage options, how concerned are you about cost?

- How open are you to storage options that involve a background check?

Betz said there have been some pilot programs handing out cable gun locks in clinical settings. That raises the question, she said, of whether health systems need to invest in providing storage devices—and in what kind of devices. “I do not know what the answer is, and I do not think we know yet what drives these kind of decisions,” she said, “but it would be great if we could know so that we could get people the devices they need and will use.”

Betz said that any actions in the realm of suicide prevention have to include language emphasizing hope and that people will get better and that these actions should also encourage patients to engage with their families or trusted loved ones. Messaging in the decision aid also normalizes the ideas that many other people go through tough times, and that temporary storage is something that many people do in the same situation. Confidentiality is important, Betz said, as a vocal minority has expressed concern about having any mention of firearms in their health record. She noted that recruiting patients at risk of suicide for her study is challenging, as is recruiting patients who own firearms and encouraging trust and honesty.

Going forward, Betz said, she hopes to see decision tools developed for adolescents and military veterans and studies carried out that look at firearm storage more generally (separate from those studies that examine the times of greatest suicide risk). She and her colleagues are also examining approaches to training providers about firearm safety, though it is not clear yet what effect it will have on patient behavior. It will be important to adjust how physicians talk to their patients in a way that is nonjudgmental. “We need to figure out how to leave our politics and our personal views outside of the exam room and learn how to really talk to and learn from both our patients and our peers, because surveys show that a large proportion of physicians also own firearms,” Betz said.

CREATING CONSENSUS:

DEVELOPING A FIREARM INJURY RESEARCH AGENDA

Concerning creating a consensus around an agenda for firearm injury research, Ranney referred to a 2013 Institute of Medicine (IOM) and National Research Council (NRC) report that outlined five areas where research was needed on firearm injury prevention: the characteristics of gun violence, needed interventions and strategies with an emphasis on policy options, gun safety technology, the effect of video games and other media on gun violence, and risk and protective factors for engaging with gun violence. The recommendations in this report, Ranney said, are at a high level and are not particularly relevant for the individual clinician in practice.

Around the same time that the IOM and NRC report came out, several medical organizations issued consensus statements on what needs to be done to prevent firearm injury and death (Dowd and Sege, 2012; Stewart and Kuhls, 2016; Streib et al., 2016; Weinberger et al., 2015). All of these calls for action were largely concerned with policy issues and were based on the best available evidence, which Ranney said has limited applicability to clinical practice. In fact, a 2016 systematic review that she and her colleagues conducted found only 53 articles examining clinician attitudes or practice patterns around firearm injury, 7 papers of low methodological quality that examined patient attitudes about firearm screening, and 12 studies—only 6 of which were randomized controlled trials—that assessed patient-level interventions (Roszko et al., 2016). “Our consensus was there was pretty much nothing for us to achieve consensus on, so let us go back to the table and start again,” Ranney said.

In response to finding scant evidence, Ranney and her collaborators assembled a group of stakeholders which included representatives of the full scope of emergency medicine, including those with tactical and military experience and Ph.D. researchers. This group started working to create a consensus agenda for what emergency physicians need to know to solve the problem of firearm injury, using a standard practice for creating a consensus agenda known as the nominal group technique (Hegger, 1986). This process started with the Haddon Matrix mentioned earlier in the workshop. The working group settled on five types of firearm violence: self-directed violence, including suicide and attempted suicide; intimate partner violence; peer violence; mass violence; and unintentional injury. A literature review by the various subgroups for different types of injury generated 61 questions, after which a round-robin discussion generated 222 potential research questions. Further refinement by the group produced a final list of 63 distinct research questions. These were eventually reduced to 59 questions with input from external stakeholders, including the tactical emergency medical service section, the public health and injury prevention committee, and the trauma

and injury prevention sections of the American College of Emergency Physicians. Of these 59 questions, 16 mapped to the 2013 IOM and NRC report. The working group published the final list in 2017 (Ranney et al., 2017).

Ranney, Betz, and Garen Wintemute also published a paper that laid out what they thought was the best-quality evidence for what physicians should be doing in the clinical space (Wintemute et al., 2016). This paper identified three conditions indicating when firearm information might be particularly relevant to the health of a patient, and potentially to others: acute risk for violence to self or others based on information or behavior; individual-level risk factors for violence to self or other or unintentional firearm injury; and being a member of a demographic group at increased risk for violence to self or others or unintentional firearm injury, such as middle-aged and older white men, young African American men, and children and adolescents.

Based on the consensus agenda, Ranney and her collaborators have been developing resources for providers, including the What You Can Do website1 and a series of handouts that can be given to providers and patients. She and others worked with the Massachusetts Attorney General’s office to identify what steps are legal for practitioners and patients to take. For example, a physician might have a domestic violence patient whose partner has a gun. “Can I tell her legally that she can take the gun to a pawn shop?” Ranney asked. In many states, doing so is illegal, she said. Working with the American Medical Association, she and her colleagues have also developed a continuing medical education module that provides advice to health care professionals.2

An example of a different type of project related to the consensus agenda is the iDOVE project, a brief intervention for violence-prone adolescents that involves automated texting. This study is ongoing, Ranney said, and its initial results were promising. Going forward, she added, thinking about innovative ways to use technology to facilitate patient–provider conversations will be important to reduce barriers for providers.

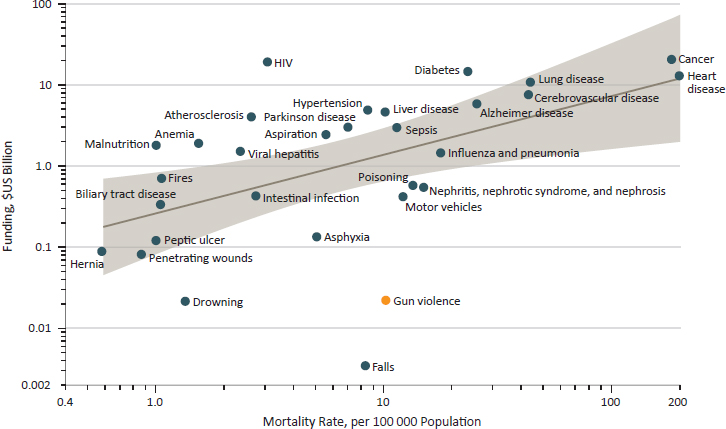

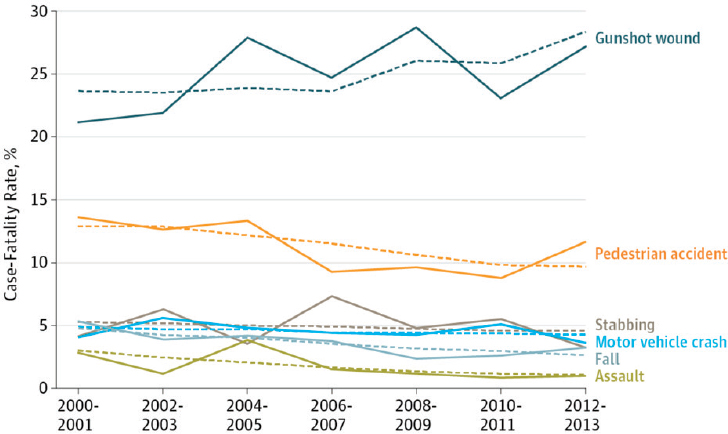

At the end of the day, she emphasized, there is still virtually no funding for this type of clinically relevant research. One analysis found that between 2004 and 2015, funding of research on gun violence was only 1.6 percent of what it should have been based on mortality burden (Stark and Shah, 2017) (see Figure 5-1). Meanwhile, the fatality rate for gunshots is rising (Sauaia et al., 2016) (see Figure 5-2). “Gunshot wounds are the only type of traumatic injury with increasing case fatality rates,” Ranney said, “and although we have these wonderful research agendas, they are just agendas

___________________

1 See https://www.ucdmc.ucdavis.edu/vprp/WYCD.html (accessed October 30, 2018).

2 The Continuing Medical Education course was released online on December 7, 2018, and is available at https://edhub.ama-assn.org/provider-referrer/5823 (accessed January 7, 2019).

SOURCES: As presented by Megan Ranney at the workshop on Health Systems Interventions to Prevent Firearm Injuries and Death on October 17, 2018; Stark and Shah, 2017.

NOTE: Unadjusted rates are the solid lines and adjusted rates are the dashed lines.

SOURCES: As presented by Megan Ranney at the workshop on Health Systems Interventions to Prevent Firearm Injuries and Death on October 17, 2018; Sauaia et al., 2016.

without funding and action. Many of us have found ways around the lack of funding to try to do our best to get answers, but without a concerted effort from our community and those that we partner with, it is not going to move forward.”

Ranney concluded her comments by reminding everyone why this work is important. “I want us to remember that the reason why we are all doing this is not for our own careers and not because we want our health systems to look awesome and not because we are searching for NIH [National Institutes of Health] funding,” she said, “but because of our communities and our patients and our friends and family members.” It is her belief, she said, that with a broad consensus that includes Americans from across the political spectrum and across every locality in the United States, reducing the human toll from gun violence is possible.

DISCUSSION

Betz said that while firearm violence in schools is increasing and is certainly a cause for concern, adolescents are far more likely to die by suicide than in a school shooting. This is something that parents need to be educated about, particularly in communities where many parents own firearms. “How do we change the message so that guns stay locked up until the kids leave the house, not when they are 13 and have taken a safety course?” Betz asked. “How do we help our patients and our communities understand those relative risks?” Ranney said that the important thing, which she credited Betz with doing, is to make sure that the voices of the people who need to hear that message are themselves heard. “Talking to a bunch of non-gun owners about how we are going to stop suicide by firearm is not the solution,” she said.

Isham asked Betz and Ranney to comment on what will be needed when handing off interventions to those who would scale and deploy them across every emergency department in a given region. Ranney, noting that there is a science behind dissemination and implementation, offered a few ideas. First, the intervention cannot require more workforce to implement, which is where technology will be helpful. Second, health system leadership will have to support implementation and encourage it to happen. Third, it will be important to provide feedback and help clinicians see the value of the intervention using evidence. Betz added that appropriate patient-facing technology will help get information to patients without making more work for clinicians. One question she had concerned how information on firearms will interface with the electronic health record.

Julie Richards from Kaiser Permanente Washington commented that in a recent training she took with social workers in her health system on safely planning with patients identified as being suicidal, she learned that

social workers who were gun owners themselves had a much easier time talking about firearms with their clients. She then asked the panelists how they get feedback from stakeholders about the effectiveness of a decision-making tool. Betz replied that she and her collaborators conducted one-on-one interviews with iterative versions of the tool as a means of identifying specific words and imagery in order to make sure that viewpoints were balanced and the words used were neutral, given that the materials would be used in a health care setting. One lesson from these interviews was that providers who do not own guns need to know more about them to avoid sounding naïve when talking to patients and losing their trust. This does not mean that providers need to become gun experts, but they do need basic information to respond intelligently and respectfully to the most common questions they will get. She said that she has never had anybody get angry at her for bringing up the subject of safe gun storage because, for example, she tries to hold that conversation from a place that is genuine.

An unidentified participant wondered if, when asking the question “How open are you to removing your gun from your household?” there is room for motivational interviewing when it is clear that removing guns from the household is not going to happen with a particular patient. Betz replied that the decision aid was designed to walk through the process with the patient and blend with motivational interviewing.

Grossman asked the panelists if having the option of invoking an extreme risk protective order (ERPO) offers potential opportunities to reduce suicide by firearm. Ranney replied that in most states, only law enforcement or a family member can initiate an ERPO. A clinician could talk to law enforcement or encourage family members to report their loved one, but in most states the belief is that if reporting becomes mandatory, as it is with domestic violence, disclosures will decrease. That said, she noted that Wintemute is conducting a study looking at the use of ERPOs. What he found so far, she said, is that there were few reports initially and more after some educational outreach occurred. “I think this is an area that is ripe for research and intervention,” Ranney said. “I think we have to be very careful to not put health care providers in a spot that will reduce help seeking.”

Betz added that ERPOs are promising for preventing harm, particularly in the context of mass shootings. In the context of suicide prevention, she said, ERPOs will likely be the last resort for most families. Betz said she hoped that as ERPOs are being evaluated, researchers will collect anecdotes and evidence on their misuse, which she has heard would be useful from her colleagues in the firearms world. “I think there are valid concerns about whether people are going to be abusing them or not, and it would be great if eventually we can have data on what is happening and which states have model laws to then think about how we as health care providers can be aware of them to potentially use them.”

Christopher Barsotti commented that collecting data on the cohort of people who have been the subject of an ERPO could provide important information on the trajectory and transition point to being at a high risk for suicide. He then asked Betz if her study includes an option of removing the firing pin from a gun, similar to the approach the military uses of removing bullets from the guns of active military personnel who are identified as being “at risk” so that these individuals do not suffer the stigma of such an identification. Betz replied that it is not an option in her program because removing the firing pin would be complicated for family members who are not familiar with a particular firearm. She did add that this option might work well for families that have a loved one with dementia who might become anxious when they find that his or her gun is missing.

Kristin Brown from the Brady Campaign and the Center to Prevent Gun Violence said that her organization embarked on a process 2 years ago to research how to talk to gun owners about the dangers of guns in the home. One piece of feedback they got from interviews with some 100 gun owners in 8 markets was that the term “gun owner” has become stigmatized in U.S. society; this does not serve the interests of the gun violence prevention movement at all, Brown said. That discovery prompted Brown and her colleagues to come up with a new term—family fire—for incidents that occur as a result of an improperly stored gun in the home and to develop a campaign focused initially on children to end family fire. She then asked the panelists for any feedback they could provide from their discussions about safe storage with their patients. Betz replied that she does not see many children in her emergency department, so all of the conversations she has had have been with adults. Ranney added that as an emergency room physician, she does not have many safe storage conversations. She did note that a study conducted a decade ago did look at motivational counseling in pediatric practices and found high acceptability and feasibility in self-reported changes in storage (Barkin et al., 2008; DuRant et al., 2007). She also called for research on how and when to have a conversation on safe storage in a way that does not alienate families. Isham added that the nature of such conversations will likely have to be region specific to reflect local attitudes about firearm ownership.