Earlier in the workshop, Tener Veenema of the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing and Bloomberg School of Public Health called attention to the persistent threat of workforce issues. The intention of Panel Discussion V, summarized here, was to focus on workforce issues with greater granularity. Moderated by John Koerner, senior special adviser, Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, High-Yield Explosive Science and Operations, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), panelists were asked to consider workforce readiness, education, training, mobilization, and deployment (e.g., willingness to respond, workforce regulation, and other potential constraints).

HEALTH WORKERS’ WILLINGNESS TO RESPOND TO NUCLEAR EVENTS

Daniel Barnett, associate professor, environmental health and engineering, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, described what he called the “ready, willing, and able” framework. Barnett explained that readiness in this context means adequate physical infrastructure, human resource infrastructure, and personal/community preparedness and that ability means adequate skills and knowledge. Willingness, Barnett said, is the attitudinal component that is too often neglected; the infrastructure and resources can be in place for a successful response, but “without willingness, it is all for naught,” he said.

Barnett described several studies that indicated overall hesitancy by health workers to respond to radiological or nuclear incidents. He said

that one important study on the topic, conducted by Cham Dallas and colleagues, analyzed relative willingness to respond to an event categorized by disaster type (Dallas et al., 2017), comparing respondents in the United States and Japan. In both countries, respondents identified a nuclear bomb as the event most likely to make them unwilling to come to work (dirty bombs and nuclear power plant accidents were included separately too). A separate 2010 study (Stevens et al., 2010) also identified nuclear threats as the threat type with the lowest perceived competence to respond among Australian health workers; Barnett said these results are in line with past research by Paul Slovic, who has found that radiological and nuclear scenarios have the highest risk perception.

Barnett turned to his own research on willingness to respond among Medical Reserve Corps volunteers, hospital employees, and public health workers, which he conducted with colleagues at Johns Hopkins University and Ben Gurion University in Israel. He explained that while their research reviewed a dirty bomb scenario (relative to other events) rather than a nuclear incident, the low rate of willingness to respond to a dirty bomb scenario does not bode well for potential willingness to respond to a nuclear incident. Barnett also pointed out that the research illuminated several interesting differences between different groups’ willingness to respond to a radiological event. For example, he said, they found that nurses are less likely than physicians to be willing to respond, a problem considering the size of the nursing cohort among the overall health care workforce in the United States. Moreover, he said, the research found no difference in willingness to respond between staff in radiology departments and other departments, a sobering result that indicates willingness to respond may go beyond understanding radiation physics. The lack of willingness, combined with the potential physical incapacitation of members of the workforce during an event, could put a large strain on surge capacity, Barnett said.

To address this problem, Barnett described a curriculum that he and colleagues designed called Public Health Infrastructure Training (PHIT), which they tested through a randomized controlled trial. The training intervention, which was intended to address the attitudinal and behavioral gaps in willingness to respond, attempted to boost public health workers’ sense of self-efficacy, which Barnett described as “confidence that one can perform one’s role.” In the model used, efficacy was given more weight than threat, so even in jurisdictions where the perceived threat of a dirty bomb scenario was low, improvement in self-efficacy increased willingness to respond. Barnett described PHIT as a “train the trainer” curriculum and said it involves several learning approaches: tabletop exercises, role-playing exercises, debrief sessions, facilitated discussions, and recaps of prior events, among others. The 7-hour curriculum is intended for use

over the course of 6 months, beginning with a discussion phase, a middle phase comprised of independent learning activities, and a final phase that incorporates experiential learning, Barnett said. Ultimately, PHIT increased willingness to respond to a radiological dirty bomb scenario regardless of severity by 14 percent. Self-efficacy saw a net increase of 25 percent over a 6-month window following the intervention period. Barnett concluded by noting that efficacy-based trainings could enhance willingness to respond across hazards, including radiological and nuclear events; he said that there is an opportunity for more exploration in the context of nuclear events because that area is still less established and researched.

A PENNSYLVANIA HEALTH CARE SYSTEM PERSPECTIVE

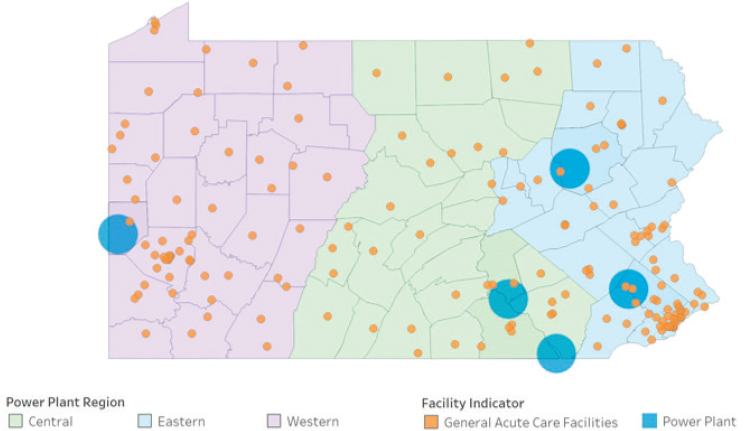

Michael Consuelos, senior vice president, clinical integration, The Hospital + Healthsystem Association of Pennsylvania (HAP), explained that nuclear preparedness in Pennsylvania largely ties back to the 1979 incident at Three Mile Island,1 during which a nuclear reactor partially melted down. The amount of radiation released had no discernable health effects on plant employees or the public, but Consuelos said the “fear factor” was large and the accident led to enhanced planning and communication. Today, Pennsylvania is home to five nuclear power plants, each with its own 10-mile-radius emergency planning zones (see Figure 8-1). Numerous acute care facilities are located across the state, accessible from any of the planning zones.

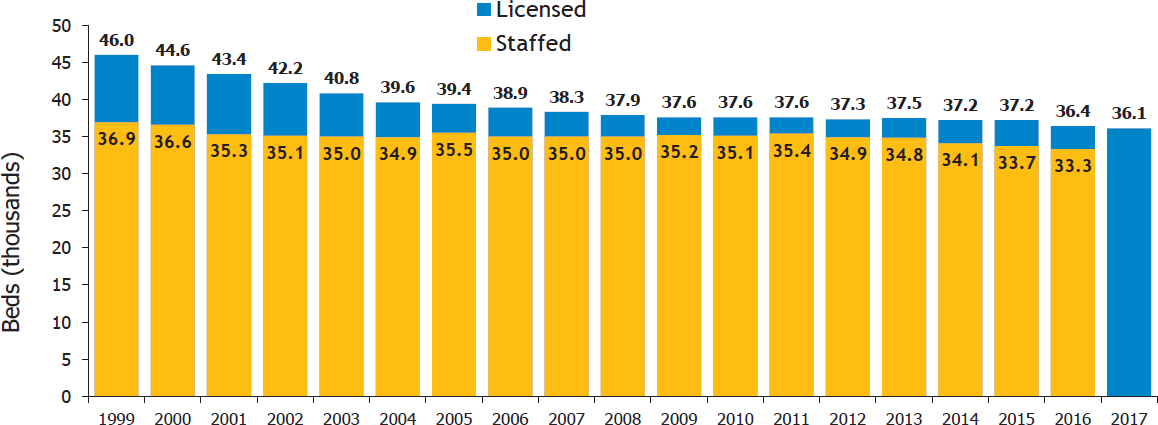

Consuelos turned his attention to hospital capacity and presented data that illustrated the number of licensed and staffed beds in Pennsylvania hospitals from 1999 through 2017 (see Figure 8-2). He noted that since 2001 the state has lost almost 17 percent of licensed beds in the state, and when correlated to staffed beds, the drop is 6 percent. While the numbers have leveled out in recent years, Consuelos commented that health care systems in general are moving toward leaner operations models to limit expenses, a problematic trend when contrasted against population growth in urban areas that would be potential targets for a nuclear attack. Currently, he said, HAP is working with an outside vendor to achieve real-time bed status data. The system pulls data on an hourly basis from hospitals’ bed management systems and categorizes them to incorporate details about usage: beds in the intensive care unit, emergency department, etc.

Consuelos pointed to seasonal influenza outbreaks as opportunities to test surge capacity in hospitals and health care systems across the country, a useful activity across hazards. Pennsylvania considers how an additional

___________________

1 For more information on the incident, see https://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/fact-sheets/3mile-isle.html (accessed December 10, 2018).

SOURCE: Consuelos presentation, August 23, 2018.

disaster during flu season would stress the system; “every disaster is a lesson to be learned,” he said. He specifically pointed to the 2017 Las Vegas shooting as an example, when numerous responders traveled outside the planned emergency medical services routes and control system. Furthermore, Consuelos highlighted nonacute care settings—including ambulatory centers, nursing homes, and rehabilitation facilities—as potential sites for screening, basic medical treatment, and decontamination during a nuclear event to lessen the burden on hospitals. Referring back to the Regional Disaster Health Response System, Consuelos said that HAP strongly supports ASPR’s plan to build the system and is actively seeking out ways to incorporate telemedicine as a way to conduct just-in-time training connecting regional centers to rural hospitals across the state.

Lastly, Consuelos addressed readiness and future needs. He said hospitals need to not only account for clinical needs but also community needs in the wake of a disaster; for example, during Hurricane Harvey, he said that several Texas hospitals stood up day care centers to meet the needs of the impacted community. Additionally, he spoke about the need to consider essential staff in hospitals. “Blurring the line between essential and nonessential individuals,” he said, “we have been talking about health care workers, but if you ask me to go find another IV bag, where are they stored in my local hospital? I don’t know where that is. And I don’t know how to operate food [preparation]. I don’t know how to clean a room well,

SOURCES: Consuelos presentation, August 23, 2018; data from the Pennsylvania Department of Health’s Annual Hospital Reports (2018).

let alone an operating room. So we need to make sure that what we call our ‘nonessential’ individuals are really essential to running the hospital.” Consuelos ended by noting the importance of Pennsylvania’s nine health care coalitions and said its day-to-day work supports small events and would be the key to handling any future disasters too.

A U.S. PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE NURSE PERSPECTIVE

The U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) was established in 1798 and includes approximately 6,500 commissioned officers (including 1,500 nurses), led by the surgeon general, serving the needs of underserved populations across the United States, said RADM Susan Orsega, chief nursing officer, USPHS. Officers are deployed to states and localities but also to many federal agencies, including the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Orsega noted that the current surgeon general, Jerome Adams, has made collaboration and partnerships in disaster response a priority. Since 1999, USPHS has deployed 15,000 officers across 500 emergency public health missions. In 2006, following Hurricane Katrina, Orsega said, an HHS guidance document recommended that the department train, organize, equip, and roster medical and public health professionals in preconfigured, deployable teams. The five Response Deployment Teams are situated across the HHS regions and provide mass care at federal medical shelters. Regional incident support teams are another HHS resource, with one team located in each region. Orsega said these teams conduct needs assessments and typically operate as liaisons between state and local/trial incident management. Specific to the national capital region, Orsega also mentioned capital area provider teams, which provide medical and public health resources during deployment for special events such as a presidential inauguration or Independence Day festivities.

Next, Orsega addressed the USPHS’s capacity and capabilities. Its capacity, she said, are the tools, technology, and accumulated knowledge that allow USPHS officers to act as subject matter experts. Its capabilities lie in the service’s teamwork and talent. She emphasized the importance of cross-sector collaboration to ensure readiness for future disasters, particularly nuclear and radiological events. She said that in the current threat environment, a fundamental capacity of USPHS is its flexibility, adaptability, and ability to create partnerships: “The readiness to act, that ability to be aware of yourself in these complex, unpredictable, and vulnerable environments, is a fundamental capacity.” She stressed that at a time when health care professionals may be exposed to unpredictable risks, the “soft technical skills” (collaboration, flexibility, etc.) add value to this cause.

NATIONAL DISASTER MEDICAL SYSTEM

The National Disaster Medical System (NDMS) takes a two-tiered approach to its management, explained Ron Miller, acting director, NDMS, ASPR. First, NDMS is a partnership that is mandated by federal statute to include HHS, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and it is intended to augment the nation’s existing medical response capability. Each federal entity brings distinct capabilities to bear, Miller said: VA brings medical emergency radiological response teams; DoD brings the National Guard and the CBRN Response Enterprise; and HHS brings NDMS teams, public health service teams, and components from CDC and NIH. Though not mandated by statute, Miller said that other federal agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Department of Justice can also play a role in NDMS responses. Miller noted that the second tier of management is specific to HHS as ASPR houses the Division of NDMS. NDMS includes 72 total teams; among them are 50 disaster medical assistance teams, 10 disaster mortuary response teams, 1 victim identification center team, 1 national veterinary response team, and 1 trauma critical team (formerly known as the International Medical Surgical Response Team). Miller described the four pillars of an NDMS response as patient movement, patient care, fatality management, and definitive care. Expanding on the pillars, Miller described NDMS components as follows:

- Provision of medical personnel (teams/individuals), supplies, and equipment to a disaster area

- Movement of patients from a disaster site to unaffected areas of the state, region, or country

- Definitive medical care at participating health care facilities in unaffected areas

- Management and coordination of the federal fatality management program

- NDMS response teams

Miller described several challenges in maintaining the NDMS workforce. First, he noted that members of NDMS teams serve episodically and are considered intermittent federal employees, not volunteers. As a result of this setup, he said, maintaining the operational skill sets of responders is crucial and difficult. NDMS does not train doctors on how to do their jobs; rather, NDMS focuses on training responders to act according to HHS and OSHA policies and regulations to ensure they are deploying safely. Tied to any NDMS response, Miller said, are the capacity and capabilities of state and local jurisdictions to which NDMS is deployed. If a jurisdiction is not

well prepared, NDMS is forced to send more personnel and take on a larger response role.

NDMS continues to evolve, Miller said. Recently, the assistant secretary for preparedness and response, Robert Kadlec, organized a council of senior leaders across federal government partners through Emergency Support Function #8 (beyond only NDMS partners) to periodically review and update policies as needed in order to ensure needs are met and redundancies are limited. Miller explained that NDMS hopes to maintain preparedness for both natural and man-made disasters and mitigate operational gaps; he provided two examples of the latter. Following Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, ASPR noticed a gap in aeromedical evacuation capabilities in terms of proper staffing. This led to a training program on operations and functions for aeromedical evacuation that was implemented a week before the workshop took place, Miller said. Additionally, ASPR initiated a case management training program following challenges during evacuation from the U.S. Virgin Islands during the 2018 hurricane season. Overall, Miller pointed to increased partner engagement as a critical next step for improving the functionality and efficiency of NDMS.

PROVIDER KNOWLEDGE OF DISASTER PREPAREDNESS

Roberta Lavin, executive dean and professor, College of Nursing, University of Tennessee, described a study that assessed clinicians’ knowledge about disaster preparedness. The multipronged study approach attempted to match core competencies in disaster preparedness—the investigators chose to use competencies outlined by the National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health (NCDMPH), Lavin said, because they were well formulated—with the educational offerings at universities (e.g., doctoral students at medical schools, nursing schools, public health schools, etc.) as well as state- and local-level professional training.

Lavin described the student survey component. Students were shown competencies and asked to rate their confidence level on a scale from 1 to 7 in their ability to complete the task. An average response over 4 (50 percent confidence) was marked green (see Table 8-1). Among the groups surveyed, Lavin noticed that the nursing students were the most confident in their abilities, which she attributed to the fact that they were already registered nurses before returning for doctoral studies, meaning they had prior experience as practicing clinicians.

Among university administrators—deans and other faculty—a separate survey showed that confidence was not nearly as high as it was among students, Lavin said. Noticeably, administrators from osteopathic medicine programs were much more confident in their teaching than were other administrators. She noted that the response rate among medical faculty was so

TABLE 8-1 Student Responses

| Confidence Regarding Disaster Preparedness Based on Education | Mean [Scale: 1–7] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPH | DNP | D.O. | M.D. | |

| Solve problems under emergency conditions (1) | 4.11 | 4.61 | 4.04 | 3.95 |

| Manage behaviors associated with emotional responses in self and others (2) | 4.29 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 4.32 |

| Act within the scope of one’s legal authority (3) | 3.59 | 4.67 | 3.96 | 3.13 |

| Facilitate collaboration with internal and external emergency response partners (4) | 3.59 | 4.2 | 3.65 | 3.37 |

| Use principles of risk and crisis communication (5) | 3.6 | 4 | 3.39 | 2.74 |

| Report information potentially relevant to the identification and control of an emergency through the chain of command (6) | 3.71 | 4.24 | 3.62 | 2.82 |

| Contribute expertise to the development of emergency plans (7) | 3.29 | 3.83 | 3.16 | 2.47 |

| Refer matters outside of one’s scope of legal authority through the chain of command (8) | 3.27 | 4.3 | 3.57 | 3.03 |

| Maintain personal/family emergency preparedness plans (9) | 3.93 | 4.7 | 3.94 | 3.63 |

| Employ protective behaviors according to changing conditions, personal limitations, and threats (10) | 3.88 | 4.44 | 3.84 | 3.32 |

| Report unresolved threats to physical and mental health through the chain of command (11) | 3.48 | 4.37 | 3.9 | 3 |

| Match antidote and prophylactic medications to specific biological/chemical agents (12) | 2.54 | 3.11 | 2.93 | 2.58 |

| Assist with triage in a large-scale emergency event (13) | 3.22 | 4.56 | 3.87 | 3.32 |

| Report an unusual set of symptoms to an epidemiologist (14) | 4.06 | 4.31 | 3.79 | 3.11 |

| Present information about degree of risk to various audiences (15) | 3.73 | 3.72 | 3.32 | 2.71 |

NOTE: DNP = Doctor of Nursing Practice; D.O. = Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine; M.D. = Doctor of Medicine; MPH = Master of Public Health.

SOURCE: Lavin presentation, August 23, 2018.

low that those results were not useful (see Table 8-2). Ultimately, Lavin said, the data demonstrated trends that both students and university administrators agree that there is inadequate education on disaster response competencies offered in these doctoral programs. Looking specifically at the NCDMPH core

TABLE 8-2 Administrator Responses

| Confidence Regarding Disaster Preparedness Competency in Program | Mean [Scale: 1–7] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPH | DNP | D.O. | M.D. | |

| Solve problems under emergency conditions (1) | 3.25 | 3.61 | 5.25 | 2 |

| Manage behaviors associated with emotional responses in self and others (2) | 3.13 | 4.14 | 6 | 2.75 |

| Act within the scope of one’s legal authority (3) | 4 | 4.39 | 6.25 | 3 |

| Facilitate collaboration with internal and external emergency response partners (4) | 3.38 | 3.65 | 5.25 | 2 |

| Use principles of risk and crisis communication (5) | 3.63 | 3.82 | 5.25 | 2 |

| Report information potentially relevant to the identification and control of an emergency through the chain of command (6) | 3.13 | 3.39 | 5 | 1.5 |

| Contribute expertise to the development of emergency plans (7) | 2.63 | 3 | 4.75 | 2 |

| Refer matters outside of one’s scope of legal authority through the chain of command (8) | 3.25 | 3.84 | 5.25 | 2 |

| Maintain personal/family emergency preparedness plans (9) | 2.25 | 3.35 | 5.25 | 1.25 |

| Employ protective behaviors according to changing conditions, personal limitations, and threats (10) | 2.75 | 3.5 | 5.5 | 1.25 |

| Report unresolved threats to physical and mental health through the chain of command (11) | 2.75 | 3.51 | 5 | 1.5 |

| Match antidote and prophylactic medications to specific biological/chemical agents (12) | 3.25 | 3.16 | 5.5 | 1.5 |

| Assist with triage in a large-scale emergency event (13) | 2.63 | 3.63 | 5.75 | 2 |

| Report an unusual set of symptoms to an epidemiologist (14) | 4 | 3.47 | 5 | 1.5 |

| Present information about degree of risk to various audiences (15) | 3.88 | 3.19 | 4.75 | 1.75 |

NOTE: DNP = Doctor of Nursing Practice; D.O. = Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine; M.D. = Doctor of Medicine; MPH = Master of Public Health.

SOURCE: Lavin presentation, August 23, 2018.

competencies, Lavin and colleagues matched survey responses with the list to check whether respondents felt they were meeting each competency. Red indicated “no,” beige indicated “somewhat” (e.g., the competency was mentioned often, if not fully taught), and green indicated “yes” (see Table 8-3).

TABLE 8-3 Crosswalk of Competencies and Survey Data

| Competencies | Student | Administration | Measure | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPH | NP | D.O. | M.D. | MPH | NP | D.O. | M.D. | ||

| 1.0 Demonstrate personal and family preparedness for disasters and public health emergencies (PHEs) | 25 | 46 | 18 | 16 | 33 | 62 | 75 | 25 | Covered moderately to thoroughly |

| 2.0 Demonstrate knowledge of one’s expected role(s) in organizational and community response plans activated during a disaster or PHE | 19 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 25 | 31 | 75 | 25 | Covered moderately to thoroughly |

| 3.0 Demonstrate situational awareness of actual/potential health hazards before, during, and after a disaster or PHE | 39 | 9 | 14 | 3 | 63 | 32 | 75 | 0 | Covered moderately to thoroughly |

| 4.0 Communicate effectively with others in a disaster or PHE | 18 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 38 | 31 | 75 | 25 | Covered moderately to thoroughly |

| 5.0 Demonstrate knowledge of personal safety measures that can be implemented in a disaster or PHE | 3.88 | 4.44 | 3.84 | 3.32 | 2.75 | 3.5 | 5.5 | 1.25 | Confidence |

| 6.0 Demonstrate knowledge of surge capacity assets, consistent with one’s role in organization, agency, and/or community response plans | 3.22 | 4.56 | 3.87 | 3.32 | 2.63 | 3.63 | 5.75 | 2 | Confidence |

| 7.0 Demonstrate knowledge of principles and practices for the clinical management of all ages and conditions affected by disasters and PHEs, in accordance with professional scope of practice | 27 | 8 | 17 | 8 | 62 | 25 | 75 | 0 | Covered moderately to thoroughly |

| 8.0 Demonstrate knowledge of public health principles and practices for the management of all ages and populations affected by disasters and PHEs | 30 | 10 | 14 | 3 | 63 | 31 | 75 | 0 | Covered moderately to thoroughly |

| 9.0 Demonstrate knowledge of ethical principles to protect the health and safety of all ages, populations, and communities affected by a disaster or PHE | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 10.0 Demonstrate knowledge of legal principles to protect the health and safety of all ages, populations, and communities affected by a disaster or PHE | 17 | 9 | 21 | 3 | 63 | 35 | 75 | 0 | Covered moderately to thoroughly |

| 11.0 Demonstrate knowledge of short- and long-term considerations for recovery of all ages, populations, and communities affected by a disaster or PHE | 12 | 7 | 13 | 3 | 25 | 23 | 75 | 0 | Covered moderately to thoroughly |

NOTE: DNP = Doctor of Nursing Practice; D.O. = Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine; M.D. = Doctor of Medicine; MPH = Master of Public Health; n.d. = no data.

SOURCE: Lavin presentation, August 23, 2018.

The results indicated an overall lack of education in disaster preparedness and response, Lavin said.

Separately, Lavin said that she and colleagues conducted interviews with 13 individuals who served as trainers to professional health care workers. A trend emerged from those conversations: Once graduates of the various professional and doctoral programs enter the real world, disaster preparedness drills are given “lip service,” but most staff do not partake in real drills. For example, she said, the average bedside nurse will never participate in a disaster preparedness drill over the course of his or her career; she expressed alarm at the lack of emphasis on disaster preparedness at both the educational and professional levels. Lavin closed by acknowledging an important gap in her research, explaining that the researchers neglected to include any survey questions about the inclusion of ethics training in programs. She emphasized the importance of ethics in this arena because of the potential institution of crisis standards of care during an emergency. Lavin investigated the inclusion of ethics in nurse practitioner doctoral programs and sampled 10 schools of various sizes across the country; only 4 offered ethics courses. She emphasized the need to investigate ethics training further in the future to ensure that future leaders and practitioners are well prepared to respond to nuclear threats and other emergency events.

NURSE WORKFORCE READINESS FOR RADIATION EMERGENCIES AND NUCLEAR EVENTS

Veenema described three studies on which she worked as part of her service as the National Academy of Medicine’s Distinguished Nurse Scholar-in-Residence for the 2017–2018 year. She said that the topic of nurse workforce readiness was important to her given her experience in the field, and she also noted that it aligned with ASPR’s desire to quantify workforce readiness in a more tangible way.

National Nurse Readiness for Radiation Emergencies and Nuclear Events: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Veenema’s first study, a systematic review, was based on the belief that the nursing workforce is a critical component of a potential public health response to a large-scale radiation or nuclear event, but there is uncertainty about nurses’ willingness or readiness to respond to such events (Veenema et al., 2019a). She listed several of the roles that nurses would likely occupy during such an event: triage for radiation exposure and contamination; decontamination; staffing community reception centers; and providing ongoing mental health counseling, health education, and intensive clinical care to patients with burn injuries, trauma injuries, or acute radiation syn-

drome (ARS). Working with the National Academies Research Center and several colleagues who attended the workshop, Veenema said she developed a detailed search strategy with detailed inclusion/exclusion criteria to examine four relevant databases (Embase, PubMed/Medline, Scopus, and Web of Science). The search, which included international literature as well, examined whether there is quantifiable empirical evidence of readiness within the nursing workforce, and it examined literature as far back as 1979 to capture the sentinel global radiation disasters in recent history. Veenema explained that the search strategy resulted in the identification of 1,796 manuscripts, of which 62 met the study’s inclusion criteria. The majority of the 62 studies were graded as being low-level evidence, and they were predominantly descriptive; in fact, many of them were narrative articles from the Japanese literature on Fukushima and other events. Through a thematic analysis, Veenema said she and colleagues identified that while themes such as education, training, and mobilization were addressed, robust metrics for measuring readiness were absent from the literature. “Our review failed to provide quantitative evidence to support that nurses in the U.S. are able and willing to serve in these roles,” she said.

National Assessment of Nursing Schools’ and Nurse Educators’ Readiness for Radiation Emergencies and Nuclear Events

The second study Veenema presented used an online radiation nuclear survey, a questionnaire adapted from previous work by Veenema, Lavin, and Couig, updated after additional input from subject matter experts in radiation and nuclear emergency preparedness (Veenema et al., 2019b). To distribute the survey, Veenema partnered with the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) and the Organization for Associate Degree Nursing (OADN) and ultimately sent 3,000 surveys to potential respondents in May 2018. The overall response rate was 20.6 percent, Veenema said. However, a deeper dive into the results showed that the response rate among AACN schools was high (72 percent) and the response rate among OADN schools was low (2.1 percent); the organizers attributed that to the timing of the survey distribution, when many associate’s degree programs were already closed for the summer.

Veenema said that participation was voluntary, but zip code was an optional response category that helped provide insight into the demographics of respondents; approximately half of respondents were administrators (e.g., deans, associate deans), and the other half were faculty with curriculum input. The results of the survey indicated that 71.5 percent of all schools of nursing in the United States that responded to the survey teach either no radiation content or less than 1 hour of radiation content. Reasons for this, according to respondents, included inadequate time in the

curriculum/schedule and a lack of a mandate by accrediting organizations, Veenema said. Others said the topic did not occur to them as a possible topic for inclusion (20.7 percent), some believed there was no perceived risk or topical importance (10.4 percent), and some were simply not sure why their school did not offer courses on the topic (22.6 percent). She expressed concern that almost one-third (31.3 percent) of respondents believed that the topic of radiation/nuclear preparedness was not an important or relevant topic to their school. Addressing competencies for responding to nuclear events, Veenema said the survey found that between 77 and 90 percent of schools did not cover this content. A number of motives were mentioned by respondents when considering what it would take to add radiation and nuclear preparedness to nursing curricula: free expert-developed course content, new requirements in the AACN guidelines, funding for new course development, or a radiation/nuclear event on U.S. soil.

Veenema also described some cognitive dissonance that seemed to exist around risk perceptions for nuclear incidents: 92.5 percent of respondents said they believed that radiation/nuclear emergency preparedness was important, but only 12.5 percent of nursing schools confirmed the existence of a radiological/nuclear disaster plan. Furthermore, 6 percent reported having drilled for such an event, and only 9.7 percent reported that faculty would know what to do during that type of emergency.

Following up on the survey results, Veenema hoped to link the perceived risk with the actual risk that each school faced. As a result, she and colleagues created a series of maps that layered information to better characterize the risk relationship. Among the data points plotted on the maps, Veenema listed the following:

- The 99 active nuclear reactors licensed to operate in the United States; these include 60 total locations, with 23 one-reactor sites and 37 sites with two or more reactors

- The top five research facilities based on their power levels: the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; the National Institute of Standards and Technology; the University of New Mexico; the University of California, Irvine; and the Atomic Energy Commission, Rhode Island

- The 80 high-level nuclear waste sites (many overlap with existing nuclear reactors)

- 50-mile emergency planning zones around nuclear sites, which is the typical distance used for radiation disaster plans

- Schools of nursing, including schools affiliated with respondents

- Geographic fault lines and affiliated slip rates

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) region mapping

Veenema noted that while analyzing these maps, she discovered that 295 schools of nursing are located in close proximity to the planning zones, and 53.7 percent of the schools were completely unaware of their proximity to radiation sources. Regarding the fault lines, she pointed to University of California, Irvine, as an example of a nuclear reactor that lies on a major fault line, with a slip rate greater than 5 millimeters. She also explained the importance of FEMA region inclusion and commented that the information is relevant not only to nursing schools but also to emergency planners across the country. Several regions—including Region 9 (West), Regions 1–3 (Northeast), and Region 5 (Midwest)—all housed dozens of schools that were unaware of their proximity to nuclear sources.

Analysis of Nurse-Specific Roles in Federal Radiation and Nuclear Disaster Planning Documents

The third and final study was still being developed at the time of the workshop, Veenema said. She said that were a nuclear incident to unfold, there is concern among nursing leadership across the country that federal response planning is built on assumptions about the capabilities of the workforce that may not be accurate. Veenema explained that this study will systematically cross-check all relevant federal planning documents related to radiation and nuclear response needs to identify which capabilities and objects are nurse dependent and the roles and responsibilities delegated to and expected from nurses and present an analysis of the results. She emphasized the importance of not only having enough nurses to respond but also having nurses who are trained with specific skills and abilities in order to successfully respond to a nuclear event. Mobility, willingness to work, and integrity of quality care will all be major concerns during a response, she commented.

MODERATOR’S SUMMARY OF OVERARCHING TOPICS

Before initiating discussion between the panelists and members of the audience, Koerner listed several overarching topics he had heard during the presentations:

- Considerations for enhancing surge capabilities in an environment where health systems are becoming leaner (this includes incorporating workers from nonacute health care settings)

- Leveraging partnerships in order to make a response more scalable and flexible as needed

- Sustaining workforce readiness beyond simple training

- The ethics of responding to an emergency in a scarce resource environment, when practices will likely differ from the day-to-day responsibilities of health care practitioners

- The importance of quantifying and defining readiness and understanding perceived versus actual risk

GAPS IN WORKFORCE READINESS AND WAYS TO CLOSE THOSE GAPS

Koerner asked the panel about common challenges in willingness to respond, based on the workshop presentations and discussion: Are the challenges systemic or organizational? Are they based on the individual? What are gaps in readiness, and how do we address the root causes at a national level? Barnett responded that willingness to respond is scenario specific, so someone may have different feelings about a nuclear event compared to another potential threat. He also stressed the importance of good motivation; just having the tools to do the job will not force people to respond.

Veenema identified four potential courses of action to close the readiness gap:

- Quantifying the direct and indirect costs of having an unprepared workforce (she said this will force leaders to grapple with the price of poor preparedness)

- Identifying and agreeing on robust metrics for quantifying readiness across disciplines

- Addressing the knowledge gap by updating medical and nursing curricula, which she described as an easy first step

- Addressing the issues around willingness to respond by taking lessons from recent disasters and doing more to consider potential workforce shortages before they happen