3

Demographic and Military Service Characteristics of Military Families

In this chapter, we present an overview of military families’ key demographic and military service characteristics in an effort to better understand these families and the extent to which the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) is meeting their needs. After first laying out the sources of this information that are available to DoD, including those both internal and external to DoD, we highlight statistics corresponding to organizational and individual characteristics of service members and their dependents. In this overview, the committee points out how DoD may be using or interpreting these statistics in assessing military family needs, and how attention to intersectionality can aid DoD in identifying any gaps or undetected patterns in these needs. Based on this overview, the committee identifies additional demographic and military service data collection and analyses that would help DoD understand how well a wider range of military families is faring and whether new or revised programs and policies are required to meet their needs. This additional input should assist DoD in meeting its obligations regarding the care of service members and their families and the readiness of the all-volunteer force.

As described in Chapter 1, the focus of this report is active and reserve component service members and their families, both while they are in the military and as they transition out of it.1 This population is heterogeneous

___________________

1 For the reserve component, the committee focuses on the Selected Reserve, which refers to the prioritized reserve personnel who typically drill and train 1 weekend a month and 2 additional weeks each year to prepare to support military operations. Other reserve elements that are not maintained at this level of readiness but could potentially be tapped for critical needs or in a crisis are the Individual Ready Reserve, Inactive National Guard, Standby Reserve, and Retired Reserve.

in ways that other chapters in this report show are relevant for understanding their experiences, their responses to those experiences, and possible strategies to help them meet their needs. Additionally, the statement of task for this study specifically requested that the committee be attentive to population subgroups and named race, ethnicity, service branch, and military status as examples. Thus, this chapter serves as a reference for the relative size of different types of key subgroups discussed throughout this report.

Because DoD’s primary family-related responsibility is to “dependent” family members (as defined in Title 37, Section 401, of the U.S. Code),2 and because most of the available information about military families concerns service members and their military dependents, that was also the primary, although not exclusive, focus of this committee. As noted in Chapter 1, a dependent family member may be

- a spouse;

- an unmarried child who is either under age 21, incapable of self-support, or under age 23 and a full-time student;

- a parent; or

- an unmarried person in the legal custody of the service member.

A child may be a child by blood, by marriage, or by adoption. A parent may be a natural parent, a step-parent, or an “in loco parentis” parent. A spouse is considered a military dependent regardless of his or her own earnings. With all of this in mind, it is important to note that there are more military dependents than there are military personnel. In 2017, there were 2,103,415 active component and Selected Reserve service members, with 2,667,909 dependents (U.S. Department of Defense [DoD], 2017, p. vi).

The committee considers the demographic information and military service characteristics presented in this chapter to be relevant for understanding

- individual and family well-being and resilience;

- how service members’ and military families’ experiences and their attitudes toward military life may vary by subgroup, service branch, military status, and other factors;

- the extent to which current DoD programs and policies are designed to meet the various needs of the full range of military families; and

- the degree to which DoD has the information it needs to understand majority and minority subgroups within this population.

___________________

2Pay and Allowances of the Uniformed Services, United States Code, 2006 Edition, Supplement 5, Title 37.

Reviewing all potentially relevant demographic and military service characteristics here is not feasible; therefore, the absence of discussion of any particular characteristics should not be construed as an indication that it is irrelevant.

INFORMATION SOURCES: WITHIN DOD

Identifying sources of information about military families is critical for understanding the availability and quality of data that DoD has at its disposal. DoD gathers and maintains certain types of demographic and military service data on service members and military dependents to assist with the organizational management of personnel (e.g., to determine their pay and make assignments), the administration of programs and benefits (e.g., for health care, housing, and tuition assistance), and statistical research (e.g., to understand reenlistment trends). DoD also routinely sponsors surveys to gather insights on the attitudes and experiences of service members and spouses, such as the perceived impact of deployments, satisfaction with military programs and services, and attitudes toward continued military service. These surveys also typically gather demographic and military service data, some of which are used to weight the analytic sample.

The surveys include the recurring active and reserve component versions of the Status of Forces surveys of service members and spouse surveys. They also include the Millennium Cohort Study and Millennium Cohort Family Study, which are longitudinal epidemiological studies of cohorts of military personnel and family members. The latter two studies focus on health and well-being, health behaviors, health conditions and symptoms, exposures (e.g., to combat, chemicals, sexual assault), aspects of military life (e.g., deployment, moves), and aspects of life in general (e.g., stressful events, self-mastery). Additionally, the family study covers issues such as family functioning and children’s behaviors and health conditions. The Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development also conducts the Million Veteran Program, a national voluntary research program that collects information from veterans to build a database of genetic, lifestyle, and health information as well as information on the military experience.3

A strength of DoD efforts is their visibility on many characteristics of the entire population of service members and contact information that can be used to solicit participation in research. Although the administrative personnel datasets will contain some missing, erroneous, or outdated information, DoD possesses much more information about this population than most organizations or scientific studies are able to access for any given population. However, DoD has much less information about dependents

___________________

3 For more information, see https://www.research.va.gov/MVP/veterans.cfm.

than about service members; in fact, dependents are often studied by making use of their related service members’ characteristics. DoD routinely publishes online4 aggregate reports of certain demographic and military service characteristics, such as the annual demographics reports sponsored by Military Community and Family Policy (MC&FP) (e.g., DoD, 2017).

This committee considered whether there are additional characteristics that DoD should be collecting information about, or additional ways MC&FP should be analyzing or sponsoring analyses of the data DoD is already collecting.

Parameters

Although DoD maintains a wealth of data, understanding the legal boundaries within which it is required to operate is essential. DoD policy and practices regarding information systems such as these must comply with the U.S. law known as the Privacy Act of 1974.5 Consequently, it is DoD policy that

- An individual’s privacy is a fundamental legal right that must be respected and protected.

(1) The DoD’s need to collect, use, maintain, or disseminate (also known and referred to in this directive as “maintain”) personally identifiable information (PII) about individuals for purposes of discharging its statutory responsibilities will be balanced against their right to be protected against unwarranted privacy invasions . . .

. . .

- PII collected, used, maintained, or disseminated will be:

(1) Relevant and necessary to accomplish a lawful DoD purpose required by statute or Executive order. (DoD, 2014, pp. 2–3).

Federal law known as the Paperwork Reduction Act of 19806 was enacted to reduce the burden on the public of government information collection. Under Title 10—Section 1782 (a), Survey of Military Families—DoD is permitted to survey service members, family members, and survivors of personnel who died while on active duty or while retired from military service “in order to determine the effectiveness of Federal programs relating to military families and the need for new programs . . .” DoD surveys of the

___________________

4 Published on the Military OneSource website at https://www.militaryonesource.mil/reportsand-surveys.

5 Privacy Act of 1974, 5 U.S.C. § 552a (1974). For related DoD policies, see DoD (2007a, 2014).

6 Paperwork Reduction Act of 1980, 44 U.S.C. §§ 3501–3521 (1980).

general public, to include military contractors, require an application to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) (DoD, 2015a), which falls under the executive branch of the government, and an approval process that may take a year or more to complete.

Consequently, although there are certainly exceptions, most available DoD data focus on service members and dependents, who as beneficiaries fall clearly within the above legal parameters. However, as the evidence in Chapter 2 demonstrates, DoD could benefit from learning more about military family members who are not dependents, such as the intimate partners of unmarried service members. Legal review may be necessary to determine whether OMB approval is necessary for primary data collection on other family members, but even if OMB review is required, an exploratory effort to solicit direct input from other family members could be illuminating in practical and policy-relevant ways.

Individual health records are maintained separately from personnel records, and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 19967 limits the sharing of certain health information. It is possible to obtain permission to link health and personnel records for research purposes, as was done for the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Kessler et al., 2013), but approvals and data safeguards must be in place, and these datasets are complex and not simple to analyze.

INFORMATION SOURCES: EXTERNAL TO DOD

External scholars and organizations are additional sources of information that can supplement official DoD data. Sources of information that focus on military personnel or family members include academic scholars in universities and research institutions (e.g., Pew Research Center, RAND Corporation), associations (e.g., Blue Star Families), and news organizations (e.g., Military Times). Additionally, broader data collection by the government, such as the Census’s American Community Survey, can include indicators of military service or military spouse status. As another example, the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health added questions to determine whether respondents had any military family association; the survey asked respondents whether they had immediate family members who were serving in the U.S. military and to specify their relationship to the service member (Lipari et al., 2016).

These data collection efforts and studies have been particularly helpful for understanding characteristics not (or not yet) collected by DoD, such as sexual orientation (e.g., Moradi and Miller, 2010), gender identity

___________________

7 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, P.L. 104-191, 110 Stat. (1996).

(e.g., Gates and Herman, 2014), and the prevalence of traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Tanielian and Jaycox, 2008). Without access to DoD databases, it can be challenging for scholars to determine how representative some of these findings are, because DoD data are necessary for obtaining contact information to construct probability samples and to assist in weighting data and in analyzing results for nonresponse bias. However, obtaining exact percentages is less important than understanding key patterns across populations, or even demonstrating whether certain subgroups exist, for example whether gay and lesbian service members were actually serving and serving openly when open service was prohibited.

ORGANIZATIONAL AND INDIVIDUAL CHARACTERISTICS

Drawing from multiple sources within and outside of DoD, in this section we describe selected key demographic and military service characteristics of military families.

Characteristics of Service Members

The demographic composition of military personnel is shaped by DoD and Service policies and strategies for recruitment and retention in the all-volunteer force. Applicants must be deemed fit for military service and fit for their particular occupation. Overarching qualification standards are outlined in DoD policy (DoD, 2015b). Waivers for certain requirements may be considered for particularly strong candidates or in times of great need. Accessions criteria may also change to meet DoD’s needs for personnel, such as during wartime, to respond to congressional mandates, or to adapt to societal or technological changes.

The courts have repeatedly deferred to congressional authority regarding military personnel law and policy related to national security interests. For example, in Rostker v. Goldberg,8 the U.S. Supreme Court determined that it was not unconstitutional to require only men to register for the draft, and that “Congress was entitled, in the exercise of its constitutional powers, to focus on the question of military need, rather than ‘equity.’” Thus, the military has not been subject to the same employment standards as civilian society. Age, gender, medical conditions, physical ability, mental ability, and other criteria are used to screen for suitability for military service or for specific occupations or positions within it, as defined by Congress, DoD, or the Services. What defines fitness for or compatibility with military service has been the crux of debates, such as whether military women should

___________________

8Rostker v. Goldberg [453 U.S. 57 (1981)].

serve in certain occupations or units (e.g., in the infantry, in special operations, or onboard submarines), whether openly gay and lesbian individuals should serve, and whether transgender individuals should serve.

Service and Component

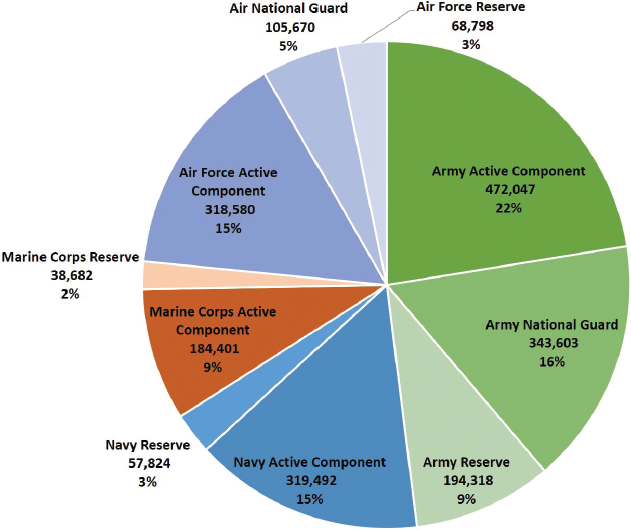

Nearly half of the 2,103,415 active and Selected Reserve service members are in the Army, as is shown in Figure 3-1. The Marine Corps, which falls under the Department of the Navy, is the smallest service. Reserve component personnel can also serve on active duty (e.g., when mobilized for a deployment), but in this figure they are grouped according to their National Guard or Reserve organizational affiliation in the reserve component, rather than with the active component. Army National Guard and Air National Guard members work for their states (under Title 32), unless they are mobilized to work under the federal government (under Title 10),

SOURCE: DoD (2017, pp. iii–iv).

NOTE: Percentages may not total to 100 due to rounding.

as they would be for an overseas military deployment. Their job requirements, eligibility for programs and services, health care system, and more can vary depending upon whether their current orders fall under Title 32 or Title 10. Reservists work for the federal government only, but like National Guard members they traditionally train 1 weekend a month and 2 weeks in the summer, although they may also be called to full-time active-duty service. Chapter 4 describes further how National Guard, reserve, and active component service context can vary.

Assigned Geographical Location

One major difference between active and reserve component service members is that the Services typically assign active component members to installations in the United States and abroad for tours that tend to last 2 to 3 years, whereas reserve component service members can generally maintain a continuous affiliation with a unit in the National Guard or Reserves. There are exceptions, of course: Some active members can have extended tours in one location, and members of the reserve component may choose to move, for example if they wish to relocate or pursue a particular position in another guard or reserve unit, or they may need to move as units close or change in composition.

In both cases, the majority of service members (88 percent active component, 99 percent reserve component) are based in the United States or its territories (DoD, 2017, pp. 31, 89). In 2017, approximately 5 percent of active component service members (70,236) were stationed in East Asia, particularly Japan and South Korea, and approximately 5 percent (65,855) were stationed in Europe, particularly Germany (DoD, 2017, p. 31).9 Approximately 1 percent of active component service members were stationed in other overseas locations or serving on ships afloat (DoD, 2017, p. 33).

Within the United States, 67 percent of active component service members are stationed in just 10 states: California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, and Washington (DoD, 2017, p. iv). Among reserve component personnel (in the National Guard or the Reserves), a slightly different set of top 10 states are home to 43 percent of personnel: California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Virginia (DoD, 2017, p. v).

Some installations are designated as “remote and isolated” by the Services (DoD, 2009a). By DoD policy, this designation allows certain morale,

___________________

9 Countries highlighted were selected from the December 2016 data reported by the DoD’s Defense Manpower Data Center under the Military and Civilian Personnel by Service/Agency by State/Country, see https://www.dmdc.osd.mil/appj/dwp/dwp_reports.jsp.

welfare, and recreational activities to receive a greater level of appropriated funds rather than relying as heavily upon income to cover their operating costs. It may be useful to consider how many service members and their families are living in this type of location, far from urban centers and main transportation hubs, because it may be more challenging for friends and family to visit them and vice versa, and they may have greater challenges finding activities or community resources to help them with their problems. Although DoD does not appear to publish aggregated statistics on how many service members are assigned to the officially designated remote and isolated locations, it does report for each U.S. installation the number of miles to the nearest metro city (DoD, 2017, pp. 176–185). Specific locations that have received this “remote and isolated” status are named in policy: In addition to many overseas locations, examples within the United States include the Naval Ordnance Test Unit in Cape Canaveral, Florida; Naval Outlying Field San Nicolas Island, California; Marine Corps Air Station, Yuma, Arizona; Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, South Carolina; the Army’s Fort Wainwright near Fairbanks, Alaska; the Army’s White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico; Minot Air Force Base, North Dakota; and Vance Air Force Base, Oklahoma (Commander Navy Installations Command, 2014, pp. 6–7; Department of the Navy, 2007, pp. 1–25; Headquarters Department of the Army, 2010, pp. 21–22; Department of the Air Force, 2009, p. 14).

In contrast to such remote and isolated locations, some military installations are in or near large urban areas. San Diego, California; San Antonio, Texas; and Norfolk, Virginia, are examples of large urban areas with large concentrations of military personnel and dependents (DoD, 2017, pp. 176–177, 183–184). Most notably, there are a number of military installations in the nation’s capital region just north and south of Washington, D.C., such as the Pentagon, Fort Meade, Fort Belvoir, Joint Base Andrews, Marine Corps Base Quantico, and the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. Additionally, the U.S. Naval Academy is located just over an hour east of the capital. Military families in this region are surrounded by a vast array of military and nonmilitary service providers, a great concentration of other current and former military families, multiple options for neighborhoods and forms of transportation, many education and employment opportunities, and endless opportunities for indoor and outdoor recreation and fitness activities for family members of all ages.

Age

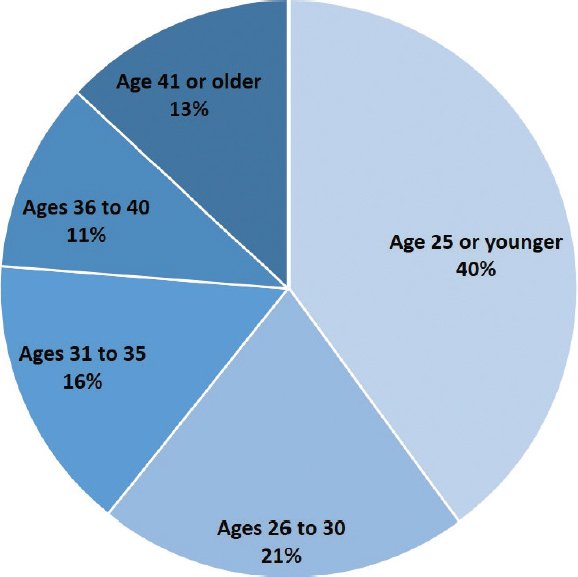

Given the physical requirements and stressors of many military occupations and assignments, the force is relatively young by design. Recruitment strategies for enlisted personnel, who comprise approximately 83 percent

SOURCE: Adapted from DoD (2017, p. 8).

NOTE: Percentages may not total to 100, due to rounding.

of the force (DoD, 2017, p. 6), target recent high school graduates, so most new recruits are under the age of 25. Officer entrants are slightly older, on average, than enlisted recruits, since they typically must hold a bachelor’s degree to be commissioned as a military officer.10 The minimum age for initial entrance into the military is 17 and the maximum age allowed by law is 42, although the maximum age varies by Service and over time. For example, in 2014 the Air Force raised the maximum age from 27 to 39, while the other Services’ age limits remained at 35 years (Army), 34 years (Navy), and 28 years (Marine Corps) (Carroll, 2014). Service members become eligible for retirement after 20 years of service, so individuals who join immediately after high school may retire before the age of 40 and may seek post-service careers.

___________________

10 Warrant officers (in all Services but the Air Force) and the Navy’s Limited Duty Officers may not need a bachelor’s degree, but in most cases they are older because they come from the enlisted force (Army warrant officer helicopter pilots being a notable exception, as prior service is not required).

As a result of these policies and recruitment strategies, as shown in Figure 3-2, 40 percent of service members are age 25 or younger, and 61 percent are age 30 or younger (DoD, 2017, p. 8). Thus, most service members are either in the process of transitioning to adulthood or are in early adulthood. This is a life stage in which many service members attempt to or begin to form families and raise children. These are also the primary childbearing ages for women. Therefore, age is a highly relevant characteristic for any study of service member and family well-being.

Education

Overall, 66 percent of military personnel have a high school diploma, General Equivalency Diploma [GED], or some college (but no degree) as their highest level of educational attainment: only 1 percent have no high school diploma or GED (DoD, 2017, p. 9). The remainder have an associate’s degree (8%), bachelor’s degree (15%), or advanced degree (8%) as their highest level of education (DoD, 2017, p. 9). As noted in the previous section, military officers must hold at least a bachelor’s degree in order to receive a military commission, however some enlisted have college degrees as well. Indeed, 11 percent of active component and 8 percent of reserve component enlisted personnel hold an associate’s degree as their highest level of education, and 8 percent of active component and 12 percent of reserve component enlisted have earned a bachelor’s or higher degree (DoD, 2017, pp. iv, 199).

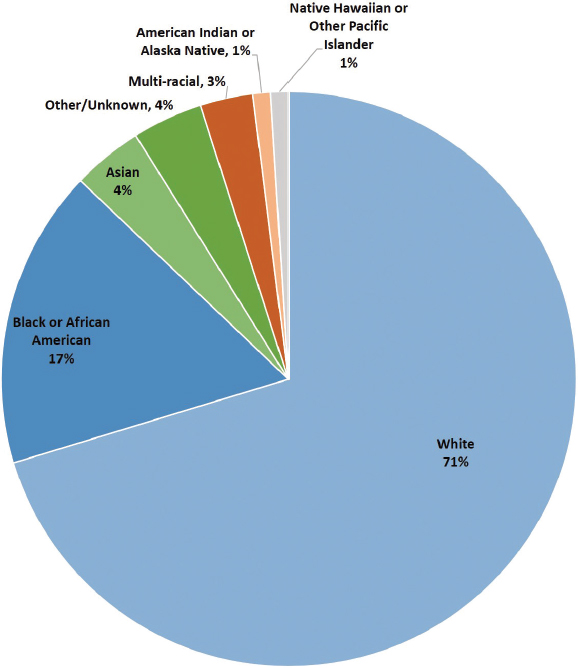

Race, Ethnicity, and Citizenship

DoD adheres to the requirements for federal program language and classification of race and ethnicity outlined in OMB’s 1997 Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity (OMB, 1997). These standards are designed to produce uniform and comparable statistics across federal agencies. Revisions to OMB’s standards have been recently considered with the aim of gathering more complete and accurate data, and a few changes are expected for the 2020 Census, so OMB standards could be revised in the future (OMB, 2017; U.S. Census Bureau, 2017; U.S. Census Bureau, 2018). Nevertheless, in this section our terminology reflects the limitations of OMB race and ethnicity categories and naming conventions that DoD uses for its data collection and reporting.

Currently the only information DoD gathers on ethnicity, as defined by OMB, is whether service members are Hispanic or Latino. According to DoD personnel administrative data files, in 2017, 14 percent of military personnel identified themselves as Hispanic or Latino (DoD, 2017, p. 8). In accordance with OMB directives, DoD does not treat Hispanic

or Latino as a minority race designation (DoD, 2017, p. iv), and reports race as a separate category. Of course, the Hispanic or Latino population in the military is racially diverse. For example, in 2017 this population made up 57 percent of active component personnel listed as having an “other” or “unknown” race, 22 percent of American Indian or Alaska Native personnel, 17 percent of White personnel, 15 percent of those who identified as multiracial, 10 percent of Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander personnel, 5 percent of Black or African American personnel, and 4 percent of Asian personnel (DoD, 2017, p. 25).

In terms of race, as defined by OMB, 71 percent of service members reported themselves as White, and 17 percent as Black or African American (DoD, 2017, p. 7). As shown in Figure 3-3, all other races, individuals

SOURCE: Adapted from DoD (2017, p. 7).

NOTES: The Army and the Army Reserve do not report “multiracial.” Percentages may not total to 100, due to rounding.

who indicate they are multiracial, and those for whom race information is unavailable make up the remaining 13 percent (DoD, 2017, p. 7).

Racial and ethnic minorities are not evenly distributed throughout the military hierarchy or across the force. For example, in the active component, 67 percent of enlisted personnel are White and 19 percent are Black or African American, but among officers 77 percent are White and 9 percent are Black or African American (DoD, 2017, pp. 24–25). Although corresponding statistics for ethnicity were not reported in DoD’s 2017 profile of the military community, from other sources we learn that approximately 18 percent of active component personnel are Hispanic or Latino, but only about 8 percent of officers are (Kamarck, 2019, p. 20). The Navy has the most racially diverse active component, while the Marine Corps has the least (DoD, 2017, p. 30). The Navy Reserve is the most racially diverse reserve component, while the least is the Air National Guard (DoD, 2017, p. 83). In the active component, the Marine Corps has the highest percentage of Hispanic or Latino personnel—21 percent—while the other three services are about 14 to 15 percent Hispanic or Latino (DoD, 2017, p. 26). There is greater variation across the reserve component, ranging from 22 percent (Marine Corps Reserve) to 6 percent (Air Force Reserve) Hispanic or Latino (DoD, 2017, p. 80).

Military service has long been a path to U.S. citizenship for immigrants; indeed, it streamlines and can expedite the naturalization process (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services [USCIS], 2018a). Since October 1, 2001, more than 125,000 immigrant service members have become naturalized citizens (USCIS, 2018b). However, because security clearances are limited to U.S. citizens and some occupations require security clearances, not all enlisted occupations are open to immigrants who are noncitizens, and availability varies by service (McIntosh et al., 2011). Additionally, regardless of race, ethnicity, country of origin, or citizenship, English proficiency is a requirement for service in the U.S. armed forces (McIntosh et al., 2011).

Although military officers and warrant officers must be U.S. citizens, DoD stated in 2015 that each year about 5,000 legal permanent resident aliens join the enlisted force (DoD, 2015c). Through Title 10 (Section 504), Congress gives the Secretary of Defense the authority to enlist individuals who are not citizens or permanent residents “if the Secretary determines that such enlistment is vital to the national interest” (p. 221 of Title 1011). In November 2008, the Military Accessions Vital to the National Interest program was approved to broaden recruitment beyond citizens and permanent residents to meet the need for particularly hard-to-fill medical, language, and cultural skills. Although approximately 10,000 immigrant

___________________

11 For access to Title 10 Section 504, see https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CPRT-112HPRT67342/pdf/CPRT-112HPRT67342.pdf.

military personnel earned citizenship through this program, DoD suspended it in 2016 and its future is uncertain (Copp, 2018).

Religion

DoD routinely collects data on the religious preferences of military personnel for practical reasons, although statistics are not commonly made publicly available. Military life can interfere with service members’ access to their religious leaders, communities, places of worship, and rituals (a good example being the last rites in Catholicism in preparation for death). Military commanders are responsible for protecting their personnel’s free exercise of religion and for preventing religious discrimination (Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2018). On that basis, the military includes a chaplain corps, places of worship in military camps and installations, community partnerships with off-base providers of religious and spiritual care, and, depending on the circumstances, accommodation of religious practices.12 Under the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the U.S. military, as a part of the federal government, cannot endorse or promote any particular religion. How the military should balance national security concerns with the religious freedoms of its members has been the subject of numerous debates throughout its history.13

The religious affiliations of U.S. military personnel today reflect a trend in the broader society, namely that of a rising proportion of adults, and young in adults in particular, who claim no religious affiliation (Hunter and Smith, 2012). DoD administrative data from 2009 showed that 20 percent reported no religious preference (Military Leadership Diversity Commission, 2010, p. 2). Some of those individuals, however, may have had preferences they were uncomfortable reporting to DoD. The majority of military personnel were recorded as affiliated with a Christian faith (69%), with the most common denominational preferences being Catholic (20%) and Baptist (14%) (Military Leadership Diversity Commission, 2010, p. 2). In 2009, non-Christian reported affiliations that made up 1 percent or more of the force were Humanist (4%), Pagan (1%), and Jewish (1%) (Military Leadership Diversity Commission, 2010).

More recent DoD administrative data focused on active duty personnel show that as of January 2019, approximately 70 percent were recorded as Christian (about 32% no denomination, 20% Catholic, 18% Protestant, 1%

___________________

12 For policy on religious accommodation, see DoD (2009b).

13 For example, United States v. Seeger and Gillette v. United States address the tension between the draft and conscientious objector status. Goldman v. Weinberger (10 USC 774) and Singh v. Carter address accommodations for religious clothing, accessories, or symbols while in uniform. For differing perspectives on policies and practices related to religion in the military, see the collection of essays in Section I of Parco and Levy, 2010.

Mormon), 2 percent as Atheist or Agnostic, 1 percent as affiliated with an Eastern religion, 0.4 percent each as Jewish or Muslim, and the remainder (about 24%) were reported as “other/unclassified/unknown” (Kamarck, 2019, pp. 46–47).

Following years of organized efforts by service members and others acting on their behalf to obtain stronger protections and support for religious diversity, in 2017 DoD nearly doubled the length of its list of faith and belief codes used to track service members’ preferences.14 DoD expects this expanded list to help it obtain and provide more accurate data, better plan for religious support to the force, and better assess the capabilities and requirements of the chaplain corps. Today’s faith and belief group codes include Agnostic, Atheist, Druid, Heathen, Magick, Pagan, Shaman, Spiritualist, and Wiccan. Changes also include more specific affiliations for existing groups, such as Orthodox Judaism, Conservative Judaism, and Reform Judaism, rather than simply Judaism.15

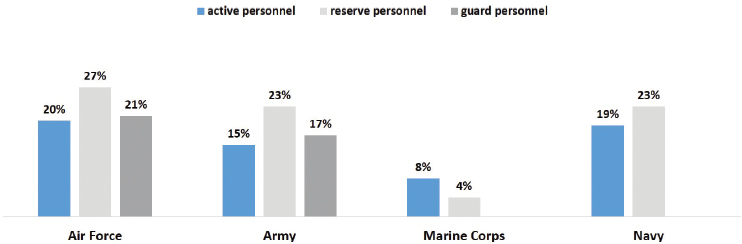

Gender

The majority of military personnel are men. In 2017, approximately 18 percent of service members (370,085) were women (DoD, 2017, p. 6). The proportion who are women varies by military affiliation (see Figure 3-4). For example, in 2017 enlisted personnel in the Marine Corps Reserve had the smallest percentage of women (about 4%) while the greatest percentage was found among officers in the Air Force Reserve (27%) (DoD, 2017, p. 72). Additionally, the percentage of women in the reserve component (20%) is higher than in the active component (16%) (DoD, 2017, p. vii).

However, the gender composition of service members’ work units and those with whom they interact may not reflect those ratios. Infantry and Special Forces units, for example, may consist entirely of men and rarely interact with service members who are women, whereas medical, administration, and supply units may have a large percentage of women service members. In fiscal year 2016, 25 percent of active component enlisted military women worked in administrative careers and nearly 15 percent were in health care, while less than 5 percent held an occupational specialty in the category of infantry, gun crews, or seamanship specialists (Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness [OUSD P&R], 2018, p. 52). In contrast, more than 20 percent of active component enlisted men served in electrical and mechanical equipment repair, and more than 15 percent worked in infantry, gun crews, and seamanship careers (OUSD P&R, 2018, p. 52).

___________________

14 For more information, see http://forumonthemilitarychaplaincy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Faith-and-Belief-Codes-for-Reporting-Personnel-Data-of-Service-Members.pdf.

15 For a complete list, see: http://forumonthemilitarychaplaincy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Faith-and-Belief-Codes-for-Reporting-Personnel-Data-of-Service-Members.pdf.

SOURCE: Information from DoD (2017, pp. 20, 72).

Gender Identity

Gender identity refers to individuals’ own sense of their gender, not individuals’ anatomy and not how others perceive them. The term cisgender refers to those whose gender identity aligns with the sex (male or female) they were assigned at birth. Transgender individuals have a gender expression or identity that does not match or is not limited to the sex they were assigned at birth. They may identify with the opposite sex, or may adopt a gender identity such as bigender, gender-fluid, third gender, or agender (genderless).16 Gender identity is independent of sexual orientation, which is a matter of which gender one is attracted to romantically and/or sexually.

In the past, DoD policy treated transgender identity as a disorder that is medically disqualifying for military service (Schaefer et al., 2016). However, in July 2015 Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter initiated a review of the policy and readiness implications of allowing transgender personnel to enter and remain in the military. He moved the authority to discharge based on gender identity up to the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness (DoD, 2015d). In October 2016, the Secretary of Defense ended the ban on transgender service (DoD, 2016a). Moreover, the Secretary announced that DoD would begin providing medical care and treatment for medically necessary gender transitions, and further stated that after transition transgender personnel must meet the military standards associated with

___________________

16 This is also distinct from intersex individuals, those whose genitalia at birth did not fit into either of the standard binary as male or female. According to DoD policy, “History of major abnormalities or defects of the genitalia, such as hermaphroditism, pseudohermaphroditism, or pure gonadal dysgenesis” is a disqualifying medical condition” (DoD, 2018a, p. 24). It is possible that some individuals whose genitalia was surgically modified entered the military with this history undetected.

their chosen gender (e.g., regarding the uniform) and use the corresponding berthing, bathroom, and shower facilities, and that DoD would treat discrimination based on gender identity as sex discrimination to be addressed through equal opportunity channels (DoD, 2016b).

Following the U.S. presidential transition in January 2017, there has been uncertainty regarding transgender service policies. Although training and other preparations were in place to begin accepting new transgender recruits as of July 1, 2017, the new Secretary of Defense, James Mattis, announced in a June 30, 2017, memo a delay to this change to allow for further evaluation of the potential impact (Kamarck, 2019, p. 41). Then the President announced his intention to revert to the pre-2016 policy and prohibit transgender service. These actions were met with legal challenges, and federal judges reviewing the cases issued injunctions against reinstating a ban (Phillips, 2018). In September 2017, the Secretary of Defense issued interim guidance that stated that the existing policies would remain in force until DoD could consult with a panel of experts and prepare new policy recommendations that would respond to the presidential memorandum (Mattis, 2017).

The Secretary’s subsequent recommendations to the President in February 2018 called for disqualification of self-identified transgender individuals, with certain exemptions for those service members who had already received a diagnosis of gender dysphoria after the ban on transgender service was lifted (DoD, 2018c). At that time, DoD reported that 937 current active-duty service members had been diagnosed with gender dysphoria since June 30, 2016 (DoD, 2018c, p. 32). Note that this figure captures only the subset of transgender personnel who revealed their transgender status to a military medical provider and who, as part of the diagnostic criteria for gender dysphoria, had also experienced distress or functional impairment because of the incongruity between their gender identity and their biological sex. In January 2019, the Supreme Court lifted the lower courts’ injunctions blocking new military policies while the legal challenges continue, meaning DoD was free to move forward with policy restricting the military service of transgender individuals (Kamarck, 2019). As of the time of this writing, it remains to be seen whether Congress will enact any legislation to support or oppose the policy, whether the policy will withstand the legal challenges, and whether the administration or DoD will modify the policy to relax or tighten the restrictions. Nevertheless, there are transgender personnel serving in the U.S. military today.

DoD administrative personnel datasets track gender, but they do not track gender identity. An analysis comparing individuals’ recorded gender over time could serve as one way to estimate the open transgender population; however, some transgender personnel may not have had their records

updated or they may feel uncomfortable self-reporting their gender identity to DoD. Additionally, changes could merely reflect data errors. Recent DoD surveys have been used to estimate how many military personnel are transgender. The 2015 DoD Health Related Behaviors Survey of active component personnel (administered November 2015–April 2016) found that

0.6 percent of service members described themselves as transgender. This is the same as the percentage of U.S. adults who describe themselves in this manner (Flores et al., 2016). Less than one percent of respondents (0.4 percent) declined to answer the transgender question. If all non-responders were in fact transgender, the overall transgender percentage would be 1.1 percent. (Meadows, et al., 2018, p. xxx).

In a weighted sample of the 151,010 participants in the 2016 Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Active Duty Members (administered as the transgender ban was being lifted, from July to October 2016), 1 percent of men and 1 percent of women identified as transgender, 1 percent of men and 1 percent of women were unsure, and 5 percent of men and 3 percent of women preferred not to respond to this question (Davis et al., 2017, p. 356). Thus, DoD estimates that approximately 1 percent of the force, or 8,980 service members, identify as transgender (DoD, 2018c, p. 7). The reserve component version of this survey was administered from August to October 2017, after the President had announced his intention to reinstate the transgender ban, and did not include a question on transgender identity (Grifka et al., 2018, Appendix D).

Using the size of DoD forces for the year 2014, one study applied a range of previous estimates of transgender prevalence derived from multiple sources (Schaefer et al., 2016). The new calculations estimated that there were between 1,320 and 6,630 transgender active component service members and between 830 and 4,160 transgender reserve component service members (Schaefer et al., 2016, pp. x–xi). Midrange estimates for the size of the transgender military population in 2014 were about 2,450 in the active component and 1,510 in the reserve component (Schaefer et al., 2016, p. xi).

Sexual Orientation

DoD does not track sexual orientation in its administrative personnel databases and thus does not publish such statistics in its annual demographics reports. However, measures were included in two recent DoD surveys on topics for which sexual orientation can be relevant.

In the 2015 DoD Health Related Behaviors Survey, nearly 6 percent of the 16,699 active component respondents identified as gay, lesbian, or bisexual (Meadows et al., 2018, p. 213). More specifically, 2 percent of men and 7

percent of women identified as gay or lesbian, and 2 percent of men and 9 percent of women identified as bisexual (Meadows et al., 2018, p. 213). Reserve component personnel were not included in this survey. The sample was weighted along other key demographic and military service characteristics.

These survey results suggest that there may be service differences as well. For example, 5 percent of Navy men identified as gay, compared to 2 percent of Air Force men, 1 percent of Army men, and less than 1 percent of Marine Corps men (Meadows et al., 2018, p. 214). There were no service differences in the proportion of men who identified as bisexual. Among women, 10 percent of Marine Corps women identified as lesbian, compared to 8 percent of Army women, 7 percent of Navy women, and 5 percent of Air Force women (Meadows et al., 2018, p. 214). Service differences were even greater for women who identified as bisexual: 19 percent of Marine Corps women, 10 percent of Navy women, and 8 percent of both Air Force and Army women (Meadows, et al., 2018, p. 214).

Another estimate comes from a weighted sample of the 151,010 participants in the 2016 Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Active Duty Members. Overall, 5 percent identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT), which represented 3 percent of men and 12 percent of women (Davis et al., 2017, p. xxii). Specifically:

- 90 percent of men and 79 percent of women identified as heterosexual or straight;

- 1 percent of men and 6 percent of women identified as gay or lesbian;

- 1 percent of men and 5 percent of women identified as bisexual;

- 1 percent of men and 2 percent of women identified as other (e.g., questioning, asexual, undecided); and

- 6 percent of men and 8 percent of women preferred not to indicate sexual orientation on the DoD survey (Davis et al., 2017, p. 356).

Even though the 2016 survey of active component members found that personnel who identify as LGBT were more likely than those who did not identify as LGBT to report experiencing sexual assault, sexual harassment, and gender discrimination (Davis et al., 2017, p. xxii), the 2017 Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Reserve Component Members did not collect data on sexual orientation (Grifka et al., 2018). Thus, LGBT estimates based on the 41,099 respondents in the National Guard and Reserves in 2017 (Grifka et al., 2018, p. iv) were not reported.

Using another approach to estimate the size of the lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) population in the military, data from the 2008 General Social Survey and 2008 American Community Survey were used to estimate that less than 1 percent of men and 3 percent of women in the active

component (about 1 percent of active component personnel overall) were LGB, but among members of the National Guard and Reserves 2 percent of men and 9 percent of women were LGB (about 3 percent overall in the reserve component) (Gates, 2010, p. 2). This would equate to about 70,781 LGB military personnel in 2008 (Gates, 2010, p. 1).

Drawing upon these survey results, if 3 to 5 percent of active and Selected Reserve service members in 2016 were sexual minorities, this would equate to between approximately 63,000 and 105,000 service members. The number of sexual minority partners, spouses, dependent teenagers, and young adults in the military family population is unknown, but comprise an even larger potential pool of people who may need assistance with and provider-sensitivity to issues related to stigma, harassment, or discrimination based on sexual orientation. These surveys also suggest that relative to military men, a disproportionate number of military women are sexual minorities.

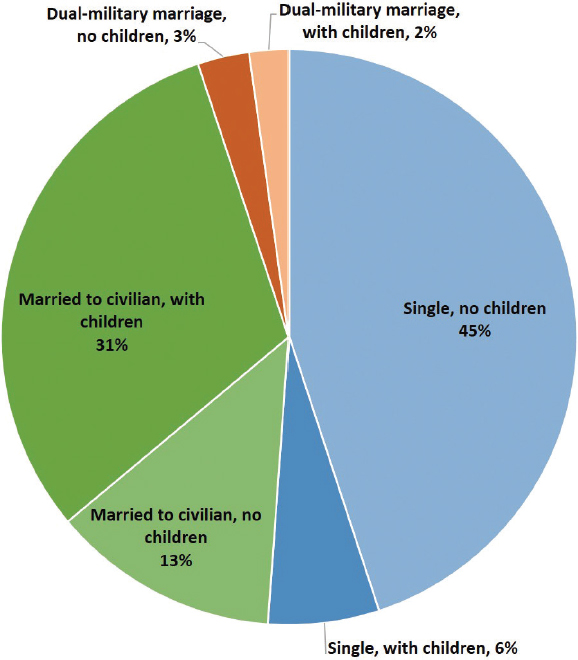

Family Status

The family status of service members, as tracked and reported by DoD, is shown in Figure 3-5 (DoD, 2017, p. 124). Overall, about 50 percent of military personnel are married, and 39 percent have children. Single parents make up about 6 percent of the force; although this is a small percentage, it represents 126,268 personnel (DoD, 2017, pp. 134, 158). About 5 percent of personnel are in dual-military marriages, meaning both members of the couple are U.S. service members (DoD, 2017, p. 124). These couples can request assignment to the same or nearby installations, although the military cannot guarantee such co-location. Similarly, they may try to manage their deployment schedules, but the needs of the military take precedence.

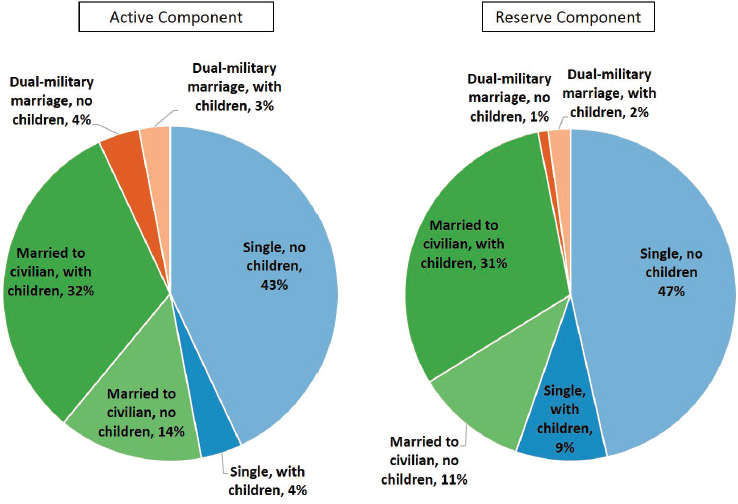

Family status differences by component are noteworthy, as Figure 3-6 shows (DoD, 2017, pp. 132, 155). A greater percentage of active component members (53%) are married compared to reserve component members (44%) (DoD, 2017, p. iv, 103). More specifically (and not shown in the figure), a greater percentage of men than women in the military are married: 54 percent vs. 45 percent, respectively, in the active component and 47 percent vs. 35 percent, respectively, in the reserve component (DoD, 2017, pp. 48, 105).

Figure 3-6 also shows that a greater percentage of members in the active component are in dual-military marriages (nearly 7%) than is the case in the reserve component (nearly 3%) (DoD, 2017, p. iv, vi). Gender differences by component are particularly noteworthy: Although not shown in the figure, approximately 20 percent of active component women and 8 percent of reserve component women are in dual-military marriages, while 4 percent of active component men and 1 percent of reserve component men are (DoD, 2017, pp. 50, 108). If the scope is narrowed to married

SOURCE: Data from DoD (2017, pp. 134, 158).

NOTES: Single includes annulled, divorced, and widowed. Married includes remarried. Children include minor dependents age 20 or younger and dependents age 22 or younger enrolled as full-time students. Percentages may not total to 100 due to rounding.

personnel, the gender and component differences are even starker: 44 percent of married active component women and 11 percent of married reserve component women are in dual-military marriages, while 7 percent of married active component men and 5 percent of married reserve component men are (DoD, 2017, pp. 51, 108).

To provide further detail on the single service member, 43 percent of active component personnel have never been married and 5 percent are unmarried but divorced (DoD, 2017, p. 46). Among reservists, 49 percent have never been married and 7 percent are unmarried but divorced (DoD, 2017, p. 103).

In demographic and survey reports, DoD typically groups divorced personnel who have remarried with other married personnel, so no overall

SOURCE: Data for the lefthand figure from DoD (2017, p. 132), and for the righthand figure from DoD (2017, p. 158).

NOTES: See Figure 3-5 concerning definitions of single, married, and children. Percentages may not total to 100, due to rounding.

statistic showing how many service members have ever gone through a divorce is readily available. The estimated percentage of married personnel who divorced in a single year (2017) was 3 percent of married active component members and 3 percent of married reserve component members (DoD, 2017, pp. 51, 109).

Unreported in DoD’s demographics profiles is how many unmarried service members are in long-term relationships and/or cohabiting with a significant other (e.g., a fiancé(e), boyfriend, or girlfriend). Although the 2015 DoD Health Related Behaviors Survey of active component personnel did include “cohabitating (living with fiancé(e), boyfriend, or girlfriend but not married)” among the marital status categories, the size of the cohabiting population was not provided separately in the survey report (Meadows, et al., 2018, pp. 30-31, 284). Through direct correspondence with the authors, however, this committee learned that 3 percent of respondents self-reported as cohabiting. The 2015 version of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health included questions to determine whether respondents had any military family association, including whether they were an unmarried partner,

TABLE 3-1 Total Number of Exceptional Family Members in 2016, by Military Service

| Service | Total |

|---|---|

| Army | 43,109 |

| Air Force | 34,885 |

| Navy | 17,553 |

| Marine Corps | 9,150 |

| Total | 104,697 |

SOURCE: Adapted from U.S. Government Accountability Office (2018, p. 12).

but it is not readily apparent from available reports how many individuals indicated they were partners (Lipari et al., 2016).

The weighted 2017 Status of Forces survey results indicate that while 57 percent of active component and 49 percent of reserve component personnel reported being married or separated, nearly 10 percent of active component and 17 percent of reserve component personnel indicated they had been in a relationship with a significant other for a year or longer (DoD, 2018b). If those survey responses are representative of the broader population, in 2017 there would have been approximately 266,964 individuals who for a year or longer had been the unmarried partner of a service member.17

Special Needs Dependents

The Exceptional Family Member Program (EFMP) provides support to military families with adult or child dependents who have special medical or educational needs (or both), including coordination support documenting family members’ special needs for personnel agencies to consider before finalizing personnel reassignments that would require relocation. Table 3-1 lists the total number of enrolled exceptional family members recorded in 2016 according to Service. As of February 2018, more than 132,500 family members are enrolled (U.S. Government Accountability Office [GAO], 2018, p. 1). Data on enrollment by age group or family relationship may be available internally, but they were not published in a 2018 GAO report on the EFMP or in the DoD’s 2017 demographics profile, nor did the 2017 Status of Forces surveys or spouse surveys include questions regarding special needs among family members. However, recently a publication by members of MC&FP indicated that about two-thirds of enrollees are military children (Whitestone and Thompson, 2016, p. 294).

___________________

17 Based on an active component population of 1,294,520 and a reserve component population of 808,895 (DoD, 2017, pp. iii, iv).

A recent survey of 160 EFMP family support providers found that the disabilities encountered by the largest percentage of providers were autism, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), emotional/behavioral disorders, speech and language disorders, developmental delays, asthma, and mental health problems (Aronson et al., 2016, p. 426).

Characteristics of Spouses and Partners

DoD administrative personnel files contain more demographic information about the service members who are employed by DoD than they do concerning their dependent family members. Still, DoD does routinely administer surveys of military spouses, which provide supplementary demographic information. DoD does not gather demographic data for its personnel files on family members who are not dependents (i.e., not beneficiaries), but some insights are available through surveys of service members or spouses that are designed to inform DoD policies, programs, and services. Recall that in DoD policy, the “dependent” status applies to all military spouses and is therefore unrelated to whether they are financially dependent upon the service member.

Across all of DoD, there are 977,954 spouses who were not military personnel themselves (DoD, 2017, p. 123).

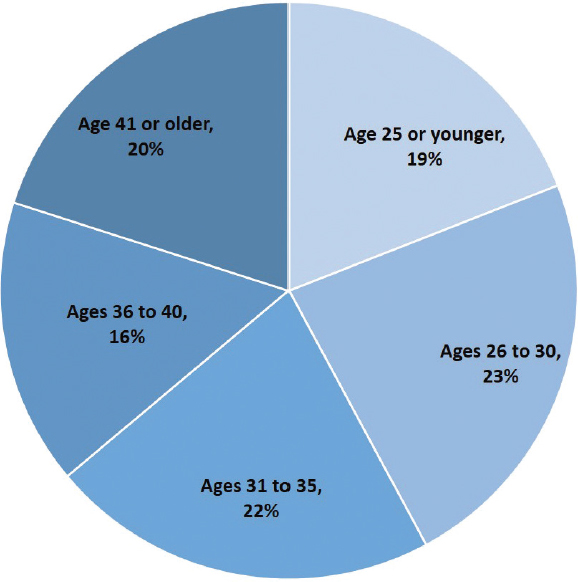

Age

Military spouses’ ages span different life stages. As shown in Figure 3-7, 19 percent are 25 years old or younger, and 20 percent are 41 years or older (DoD, 2017, p. 125). Thus, the population will include those in the early stages of adulthood, parenthood, education, and career development as well as those with established careers and children who are adults. The average age of active component spouses is 32, while the average age of reserve component spouses is 36 (DoD, 2017, pp. 137, 161).

Race, Ethnicity, and Citizenship

DoD survey data provide sources of information about the race and ethnicity of spouses and use the same race and ethnicity categories asked of service members. A weighted sample of participants in the 2017 Survey of Active Duty Spouses shows that 61 percent were non-Hispanic White and 38 percent were Hispanic and/or of other races (DoD, 2018b). More specifically, 11 percent were non-Hispanic Black and 15 percent were Hispanic (DoD, 2018b). Similarly, in a longitudinal survey of active component military spouses administered in 2010, 2011, and 2012, 70 percent were non-Hispanic White and 30 percent were minority race/ethnicity (DMDC, 2015, p. 10).

SOURCE: Adapted from DoD (2017, p. 125).

NOTE: Percentages may not total to 100, due to rounding.

A weighted sample of participants in the 2017 Survey of Reserve Component Spouses shows that 71 percent were non-Hispanic White, and 29 percent were Hispanic and/or of other races (DoD, 2018b). More specifically, 9 percent were non-Hispanic Black and 12 percent were Hispanic (DoD, 2018b). If the spouse survey results are representative of the spouse population at large, a greater percentage of active component spouses are racial or ethnic minorities compared to reserve component spouses.

Unfortunately, the committee is unaware of any published statistics on the citizenship status of spouses extracted from administrative records, and DoD’s recurring spouse surveys do not currently ask spouses about their citizenship. Spouses of U.S. service members who are not U.S. citizens may be eligible for expedited or overseas naturalization, and service members’ children may also be eligible for overseas naturalization (Stock, 2013; USCIS, 2018c). U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services reports that in the approximately 10 years since fiscal year 2008, 2,925 military spouses have been naturalized in ceremonies overseas in more than 35 countries

(USCIS, 2017). Those countries are quite diverse and include Afghanistan, Australia, Chile, China, Germany, India, Norway, Oman, Panama, Philippines, Poland, Tanzania, and Turkey (USCIS, 2017).

It appears that the last time the spouse surveys asked about citizenship was in 2006. At that time, 7 percent of the 11,953 active component spouse respondents to that question (n = 781) reported not being a U.S. citizen, and 6 percent (n = 669) reported being a U.S. citizen by naturalization (DMDC, 2007a, p. H-12). In the same 2006 survey, 13 percent of active component spouse participants (n = 1,520) indicated that English was a second language for them (DMDC, 2007a, p. H-493). Although citizenship and English as a second language questions were included in the 2006 reserve component spouse survey, the results were not included in the results report (DMDC, 2007b, App., p. 2). Thus, this important information may not be visible to leaders or program managers or nonmilitary organizations who might rely upon published demographic reports or surveys to help them understand and prioritize the potential needs of the military spouse population.

Religion

The committee is unaware of any statistics on the religious affiliation of military spouses or partners.

Gender

The vast majority of military spouses are women: 92 percent of active component spouses and 87 percent of reserve component spouses are women (DoD, 2017, pp. 136, 160). Although their presence may seem small when expressed as a percentage, military spouses who are men are nevertheless large in number (100,723) (DoD, 2017, pp. 136, 160).

Sexual Orientation

Currently married gay and lesbian service members and their same-sex spouses are technically eligible for the same military benefits as their heterosexual counterparts, including health care for spouses and the higher “with dependents” basic allowance for housing. This equality also extends to benefits from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). However, we caution that eligibility does not mean that same-sex spouses are equally comfortable self-identifying or applying for DoD or VA benefits or that they are treated equitably or to the same standard of care as their heterosexual counterparts. Indeed, even in the broader U.S. society, stigma, fear of discrimination from providers, and provider knowledge about and attitudes

toward sexual minorities can present barriers to equitable health care and associated detriments to overall well-being (Institute of Medicine, 2011).

DoD’s most recent published demographics report (DoD, 2017) does not provide statistics for the number of registered same-sex marriages among military personnel, and other estimates were not readily available.

Education, Employment, and Earnings

Among spouse participants in the 2017 Survey of Active Duty Spouses, 10 percent of the weighted sample reported having no college, while 44 percent reported having some college or a vocational diploma, 30 percent reported having a 4-year degree, and 15 percent reported having a graduate or professional degree (DoD, 2018b). The 2017 DoD Survey of Reserve Component Spouses measured education level slightly differently: 46 percent of the weighted sample reported having no college or some college, 33 percent a 4-year degree, and 21 percent a graduate or professional degree (DoD, 2018b).

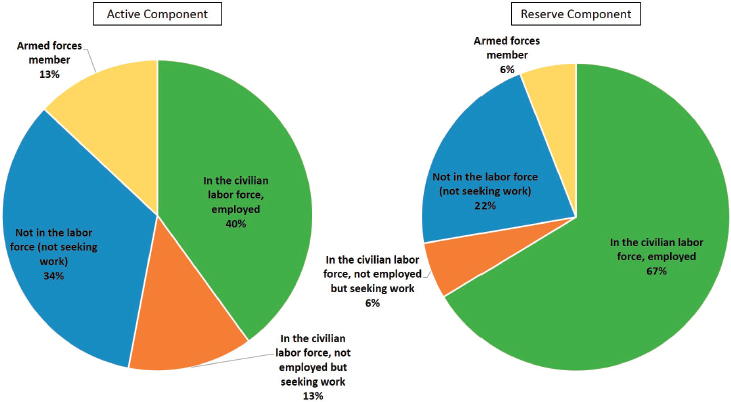

These spouse surveys suggest that active component spouses are less likely than their reserve component counterparts to be employed (53% compared to 73%, as seen in Figure 3-8). At the time of the survey, 13 percent of

SOURCE: DoD (2018b).

NOTE: Categories are constructed from multiple 2017 spouse survey items to conform to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ standards using Current Population Survey labor force items. Percentages may not total to 100, due to rounding.

active component spouses were not employed but seeking work, compared to 6 percent of reserve component spouses. Since unemployment rates exclude those who are not in the labor force (i.e., not working and not seeking work), the unemployment rate among the active component spouse respondents was 19 percent, compared to 7 percent for reserve component spouse respondents. Note that 34 percent of active component spouses and 22 percent of reserve component spouses were not working nor seeking work.

One recent study using DoD administrative data and Social Security Administration earnings data for civilian spouses of active component military members between 2000 and 2012 found that, on average, 67 percent of military spouses were working (defined as having any earnings in a given year) (Burke and Miller, 2018, p. 1269). Average annual earnings across all of these military spouses was $15,301, and across working military spouses it was $22,812 (Burke and Miller, 2018, p. 1269). The average annual earnings for the service members of these spouses in this same period was $55,367 (Burke and Miller, 2018, p. 1269). A military move was associated with a $2,100, or 14 percent, decline in average spousal earnings during the year of the move (Burke and Miller, 2018, p. 1261).

Children

The total number of children who are identified as military dependents is 1,678,778 (DoD, 2017, p. 124). Across DoD, 40 percent of all service members (831,870) have children who are minor dependents age 20 or younger, or up to age 22 if enrolled as a full-time student (DoD, 2017, p. 124). In the active component, the Marine Corps has the lowest percentage of service members with children (26%), while the Army has the highest (44%) (DoD, 2017, p. 140). In the reserve component, the Marine Corps Reserve stands out as having the lowest percentage of service members with children (20%), while between 38 and 50 percent of personnel in the other Selected Reserve components have children (DoD, 2017, p. 164).

DoD routinely publishes a few other characteristics of parents as well. About 60 percent of active component children and reserve component children have military parents who are NCOs (paygrades E-5 to E-9) (DoD, 2017, pp. 140, 164). Service members’ average age at the birth of their first child is 26 in the active component and 28 in the reserve component (DoD, 2017, pp. 140, 165).

Age of Children

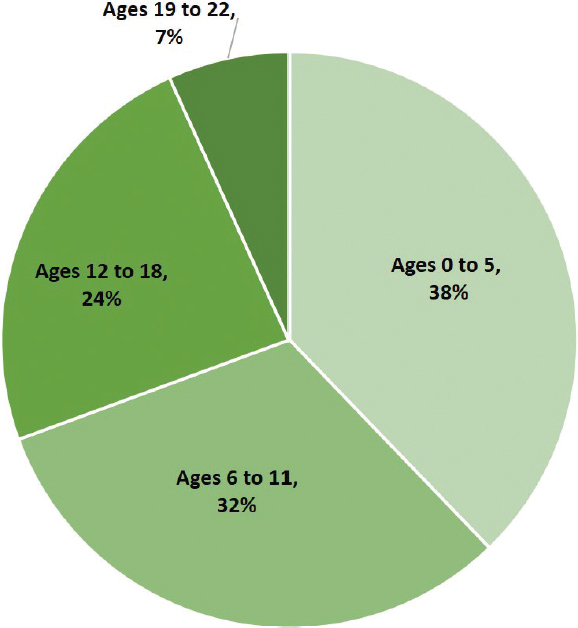

Reflecting the relatively young age of military personnel, the majority of military children have not yet reached their teens, as seen in Figure 3-9. Though not shown in the figure, a greater percentage of active component

SOURCE: Adapted from DoD (2017, p. 125).

NOTE: Children ages 21 to 22 must be enrolled as full-time students in order to qualify as dependents. Data are presented for the total DoD military force; therefore, DHS Coast Guard Active Duty and DHS Coast Guard Reserve are not included. Percentages may not total to 100, due to rounding.

children are ages 5 or younger compared to children in the reserve component (42% and 31%, respectively) (DoD, 2017, pp. 143, 167). While this youngest age group is also the largest age group among active component children, reserve component children ages 6 to 11 make up 32 percent, or about the same percentage as those who are ages 5 or younger (31%) (DoD, 2017, pp. 143, 167). DoD includes “children” ages 19 to 22 in these statistics because, as noted in Chapter 1, by law (Title 37 U.S.C. Section 401) adult children retain eligibility to be military dependents until age 21, or until age 23 if enrolled fulltime at an approved institution of higher learning (or longer if they are disabled, and then they become “adult dependents”). Thus, service members’ children can benefit from the support of access to military health care and many other resources as they work on their own

transitions to adulthood (e.g., internship, entry-level job, college, starting a business).

Education

Out of the 1.68 million military children today, about 56 percent (more than 933,000) fall into the K–12 education range of 6–18 years of age (DoD, 2017, p. 125). Approximately 60 percent of the children in active-duty military families residing in the United States are school age, and the majority of them (nearly 80 percent) attend public schools (U.S. Department of Defense Education Activity [DoDEA], 2019a). A majority of the more than 443,000 children of National Guard and Reserve members also attend public schools (DoDEA, 2019a). Additionally, more than 71,000 military-connected children attend one of the 164 accredited DoD schools (including one virtual school) run by the U.S. Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA), which are located across 11 foreign countries, 7 states, Guam, and Puerto Rico (DoDEA, 2019b). (See Box 3-1 for more information on the recognition of military connected students in public schools.)

Other Child Demographics

Even though children represent such a significant number and proportion of the military community, unfortunately several key demographics with relevance for the potential needs of military children are missing from DoD’s demographic profiles of the military community. These include the race and ethnicity of military children, which the committee’s statement of task specifically asked us to consider. Because of adoption, blended families, and interracial coupling, parents’ race and ethnicity cannot be presumed to be proxies for their children’s. The demographics profiles also do not make readily available statistics on children’s school status (DoD, public, private, homeschool), EFMP status, whether they live on- or off-base, whether they live in the United States or not, whether they live with the service member or not, and so on.

Other Family Members, Friends, and Neighbors

Other family members, such as parents, siblings, grandparents—and even friends and neighbors whom service members self-define as “family”—can be an important part of a military family’s support network, and the converse may be true as well: These people may depend on military personnel for financial or other support. Service members may still have co-parenting relationships with former spouses or partners as well. Additionally, some of the individuals in a service member’s primary network may be military personnel themselves.

TABLE 3-2 2013 Characteristics of Caregivers of Military Personnel and Veterans Who Served Post-9/11

| Relation to Care Recipient | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Spouses, Partners, or Significant Others | 33 |

| Parents | 25 |

| Friends or Neighbors | 23 |

| Child | 6 |

| Other Family | 10 |

SOURCE: Adapted from Ramchand et al. (2014, p. 34).

Other family members besides spouses or partners may provide support to service members. For example, individuals may be caregivers to service members who have a disabling physical or mental wound, injury, or illness. Table 3-2 summarizes one recent effort to understand the hidden population of caregivers through a probability-based survey in 2013 of caregivers of military personnel and veterans who served post-9/11 (after September 11, 2001). The 2007 DoD Task Force on Mental Health recommended that DoD improve coordination of care by facilitating access to military installations for those caregivers who do not have military identification cards but are caring either for military children during a parent’s deployment or for wounded service members (U.S. DoD Task Force on Mental Health, 2007, pp. 36–37).

Family members are involved in supporting military families in numerous other ways: providing emotional and social support, attending graduation from basic training or promotion or retirement ceremonies, sending letters and care packages, serving as an emergency contact, providing the “home” that service members and their families visit while on leave, holding power of attorney during deployments, storing property or caring for pets or children during deployments, providing child care even when service members are not deployed, helping during emergencies (e.g., after flood or fire), and so on.

Others may also depend on military families for support. Adults who hold the status of military dependents could include grown children, former spouses, siblings, parents, grandparents, or others in the legal custody of a service member. In 2017, there were 8,988 adult dependents of active component service members and 1,591 adult dependents of DoD reserve component members (10,579 adult dependents) (DoD, 2017, p. 145; 2019b). Less than 1 percent of active component dependents (0.6 percent) and less than one-half of a percent of reserve component dependents are adult dependents who are not the spouses or children of service members (DoD, 2017, pp. vii, 130, 151; 2019b). The age distribution of adult dependents suggests that National Guard and Reserve families with adult dependents are

most likely to be caring for parents or grandparents, given that 57 percent of them are age 63 or older. By contrast, active component families with adult dependents are most likely to be caring for grown children, siblings, or former spouses, since only 33 percent of these dependents are age 63 or older (DoD, 2017, p. 145; 2019b).

Military families may also be providing financial or social support to friends and family. They may be helping out during others’ deployments, when they have serious health problems, or during natural disasters or other times of need by assisting with child care, temporary housing, managing the household (e.g., repairs, yardwork), or organizing food or clothing drives, among other things. Other friends and family members may also be seriously impacted by what happens to military families, such as when a family member is assigned or deployed far away from them, seriously injured, sexually assaulted, killed, or has taken their own life. These relationships remain unidentified in official reports.

Thus, the military families and others that service members support and rely upon extend beyond spouses, partners, and children, even though by far the most is known about the size and characteristics of spouses and children. If every service member had just three individuals they considered to be close relatives or friends—parents, step-parents, parents-in-law, aunts, uncles, grandparents, siblings, friends, etc.—then the size of this population would be 6,310,245. These individuals may find it challenging to connect with others in their same situation and to learn which, if any, military-sponsored activities or resources might be open to them to help them better support military families.

CHARACTERISTICS THAT CHANGE OVER TIME

It is important to track trends in characteristics like these, as they may vary over time. To illustrate very simply, we highlight a few examples of how active component characteristics at the end of the Cold War, in 1990, differ from those reported in 2017. Keep in mind that demographics can fluctuate over time, so differences between two points in time cannot be assumed to represent a steady, gradual change in the same direction from year to year. Also, some demographics may remain relatively stable, such as average age (about age 24 for enlisted personnel and age 35 for officers (DoD, 2007b, p. 25; 2017, p. 40).

- Education: In 1990, less than 3 percent of the enlisted active duty force held a bachelor’s or advanced degree; by 2017 that was true for about 8 percent (DoD, 2007b, p. 28; 2017, p. iv).

- Race and ethnicity: Changes to the way race and ethnicity data have been collected and reported present some challenges to long-term

- comparisons. Nevertheless, in 1990, racial minorities (not coded to include White Hispanics) were about 25 percent of the active component, compared to 31 percent in 2017 (DoD, 2007b, p. 19; 2017, p. iii). Hispanic representation, which per U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM) guidance has been treated as its own separate ethnicity category since 2003, rose from 9 percent in 2004 to 16 percent in 2017 (DoD, 2004, p. 13; 2017, p. iv).

- Gender: The proportion who are women has been gradually increasing. In 1990, 11 percent of active-duty enlisted personnel and 12 percent of officers were women, compared with 16 percent and 18 percent, respectively, in 2017 (DoD, 2007b, p. 13; 2017, p. iii).

- Family Status: In 1990, 57 percent of active-duty personnel were married, compared with 53 percent in 2017 (DoD, 2007b, p. 35; 2017, pp. 45–46). In 1990, 39 percent of personnel were married with children, while in 2017, 34 percent were, although the percent of single parents was the same in both years (4%) (DoD, 2007b, p. 45; 2017, p. vi).

Much to its credit, DoD does indeed track and report overall trends on broad categories like these, and sometimes breaks out trends for one characteristic by another (e.g., by service or gender).

ATTENTION TO INTERSECTIONALITY

To better understand military personnel and their families, it is important to remember that the characteristics described throughout this chapter intersect with one another and countless other statuses not mentioned here (e.g., religion/spirituality, native language). In other words, intersectionality refers to the observation that characteristics are interrelated and interact with one another. No one’s experiences are defined by a single characteristic, such as gender, and the relevance of a characteristic may vary depending on the time, place, context, and other characteristics. For example, the experiences of Black women are not necessarily similar to those of White women or Black men: Examining survey results or health statistics only by gender or by race may miss important patterns, such as varying risk factors for negative outcomes. No subgroup is monolithic, so Black women’s experiences will vary as well, and they will interact with other statuses and contexts—such as being a naval officer, being a pilot, having a Marine husband, having no children, being stationed on an aircraft carrier, or being 30 years old. Likewise, an individual can hold majority and minority statuses at the same time (e.g., being heterosexual and Hispanic) and can belong to a subgroup that is a numerical majority (e.g., being enlisted) without necessarily being in a position of privilege or power.

As an illustrative example of an intersectional approach with implications for well-being, one sociological study using a survey of a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults examined whether the intersections of race, ethnicity, foreign- or U.S.-born status, gender, and socioeconomic status were associated with individuals’ perceived need for mental health care (Villatoro et al., 2018). The analyses included not only the total sample but subsamples of respondents who did and did not appear to meet diagnostic criteria for a psychiatric disorder. The researchers found that “men are less likely than women to have a perceived need [for mental health care], but only among non-Latino whites and African Americans. Foreign-born immigrants have lower perceived need than U.S.-born persons, but only among Asian Americans” (Villatoro et al., 2018 p. 1).

From a programmatic perspective, the significance of a greater appreciation of the complexity of the population is that “identifying the statuses and mechanisms that lead to differential self-labeling [as having a need for treatment for mental health-related problems] is essential to explaining why disparities in mental health care utilization exist (Villatoro et al., 2018 p. 20).” Of course, it is important to explore other potential explanations for differences in utilization of mental health care as well, such as language or cultural barriers, lack of awareness of service options, differing perceptions of or experiences with mental health care providers, and so on.

Paying greater attention to intersectionality could help DoD look for gaps and previously undetected patterns that might call for differing approaches to outreach or intervention and also help DoD affirm its commitment to a diverse range of military personnel and families. It may also help support recruitment and retention goals by promoting better attention to the varied interests, strengths, disadvantages, and needs of the myriad populations that could or do serve in the military.

This chapter has contained examples of how demographic characteristics vary by other characteristics, such as how the gender composition of service members varies by branch and occupational specialty. Many possibilities for detailed subgroup statistics exist within DoD personnel databases but are not routinely published. For example, statistics on race/ethnicity by gender by rank are not currently available. Compiling a complete cross-listing of all characteristics that DoD tracks would itself be a monumental task, beyond the scope of this study, and would be costly and impractical for DoD to produce. However, DoD can focus on the intersections that the literature shows are relevant for individual and family well-being and resilience, and for retention and readiness, or for which there is evidence or plausible reason to believe there could be important differences.

One of the purposes of this study is to help DoD think about how service member and family well-being and appropriate interventions can vary by demographic and military service characteristics. In this report, the committee has highlighted certain intersections as they relate to well-being, but there are other important intersections beyond those specifically named that could matter as well.

VETERAN POPULATION