6

High-Stress Events, Family Resilience Processes, and Military Family Well-Being

In this chapter we expand on Chapter 5’s discussion of stress among military children to address high-stress events experienced by military families. We begin with a review of the literature on stress and family resilience processes (as defined in Chapter 2) to better understand the effects of stress on family well-being. The chapter then places this understanding within the military context by discussing the effects of high impact duty-related stressors, such as physical injury, psychological trauma, bereavement, family violence and child maltreatment to illustrate how stressful challenges can impact family resilience and in turn complicate family well-being. To further elaborate on military family stressors, we describe the risk processes that characterize them and then link these processes to targets for evidence-based practices.1 We briefly highlight examples of evidence-based military family intervention programs in preparation for their more detailed examination in subsequent chapters.

As discussed in prior chapters, military children and families constitute an increasingly diverse and complex population that possesses many advantages in comparison to their civilian counterparts. As presented in Chapter 4, military families face particular experiences associated with military service, including multiple family relocations and separations that lead to transitions in residence, communities, jobs, child care, health care, and schools. These transitions can also create opportunities for new experiences,

___________________

1 Evidence-based and evidence-informed practices are defined in Chapter 1 and discussed elsewhere (see Chapters 7 and 8); the programs discussed in this chapter are specifically evidence-based.

allow family members to access previously untested strengths, and lead to successful solutions that bring a sense of accomplishment and pride. However, some challenges, for which a family may be unprepared or ill-equipped also result in high levels of stress that are likely to disrupt access to health care or other required community resources. Certain military family challenges create levels of stress and burden that predictably overwhelm most families, if only temporarily. When highly stressful challenges related to military life overtake the capacity of individuals and families to manage, they are likely to undermine the healthy resilience processes that support family functioning, leading to cascading risk and reduction in subjective, objective, and functional well-being.

While this report addresses a broad spectrum of the experiences of military families, this chapter focuses on military families’ most stressful challenges, such as combat or other duty-related mental or physical injuries and military-duty-related deaths, which can undermine family well-being by disrupting normative processes that support family resilience. Family violence and child maltreatment are additional examples of stressful challenges to families, as well as examples of maladaptive responses within overwhelmed, highly reactive, or unskilled families. This chapter underscores that all family stressors are experienced within the emerging developmental context of a family and its individual members, as well as any prior traumatic exposures or adverse childhood experiences, medical or psychiatric pre-existing conditions, the maturity and sophistication of individual family members, and other family contexts that likely moderate the effects of stress.

Unfortunately, most discussions of military family stress tend to be deficit-focused, highlighting pathology within families, an approach that only serves to further marginalize and increase their vulnerability. The present chapter parts from such historical emphases by conceptualizing how stress undermines normative and protective processes inherent to families, undermining well-being and creating risk. Employing developmental ecological and life-course models (previously described in Chapter 2), as well as the concept of “linked lives,” this chapter illustrates the complex interactive effects of high-stress events among adults and children within families and highlights opportunities to activate protective pathways that promote individual and family well-being. The chapter concludes by linking malleable risk processes to evidence-based interventions shown to mitigate the effects of stress in military or civilian families.

STRESS AND FAMILY RESILIENCE PROCESSES

Consistent with conceptualizations of individual and family risk and resilience described earlier in this volume, this chapter frames stressful family experiences in a broadly ecological context (Bronfenbrenner and Morris,

2006; Sameroff, 2010). Stress can affect micro-, meso- and macro-levels of the ecological system affecting military families (see Chapter 2). Wartime stress has been shown to have varying and often negative effects on individual service members (Hoge et al., 2006; Tanielian and Jaycox, 2008), military spouses (Leroux et al., 2016; Mansfield et al., 2010), and military children (Cozza and Lerner, 2013; Siegel et al., 2013). Most importantly, an understanding of the effects of stress on family well-being requires much more than a summation of the effects of stress on individuals within the family. Individuals are affected by and can benefit from the relational processes within families that are both multifaceted and are managed across time, and it is to those effects that we now turn.

Family Stress Models

Family stress models (Conger et al., 2002; Simons et al., 2016) provide a conceptual framework for understanding how stressful contexts such as individual psychopathology, marital transitions, and socioeconomic conditions reverberate in the family and create complex effects among individuals (adults and children), in dyadic relationships (marital and parent-child), and more broadly within families. These models were first proposed to describe how socioeconomic stressors affect families (Conger et al., 2002; Elder et al., 1986), with empirical data indicating that poverty increases parental stress, adversely affecting parenting practices, ultimately impairing child functioning and adjustment (Simons et al., 2016).

Extending this model to military families, Gewirtz and colleagues (2018b) tested a Military Family Stress Model in a sample of 336 post-deployment reserve component military families. Their work revealed reciprocal paths between parental functioning (i.e., posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD] symptoms), parenting practices, couple adjustment, and children’s symptoms. Parenting practices mediated the associations between mothers’ PTSD symptoms and poorer child adjustment; parenting also linked associations between couple adjustment and children’s behavioral and emotional symptoms (Gewirtz et al., 2018a). In effect, family stress models posit that family stressors negatively impact family well-being by undermining distinct couple, parenting, and family-resilience processes that are necessary to effectively manage overwhelming stress. These relational processes are now discussed.

A Transactional Concept of Stress

A transactional conceptualization of stress extends beyond its effect on individuals, and describes its dyadic effects within couples. As described by Bodenmann (1997), such a conceptualization “has to take into account the dynamic interplay between both partners, the origin of the stress

experienced by each individual alone or by both together, the goals of each partner or dyad as well as the coping strategies applied. . .” (p. 138). Notably, stressors tend to undermine the healthy processes within couples that are also most likely to support individuals and couples when faced with challenging experiences. Story and Bradbury (2004) summarize dyadic resilience processes that are likely to protect couples faced with stress, including active engagement and protective buffering. Active engagement refers to maximizing positive interactions through problem solving, empathic listening, expressions of caring, and constructive criticism. Protective buffering includes minimizing negative interactions through conflict avoidance and minimizing emotional distress through disengagement.

Several researchers have examined the contribution of dyadic processes to military and veteran couple health outcomes. For example, Knobloch and colleagues (2013) and Knobloch and Theiss (2011) described the contribution of relational uncertainty (lower degree of partner confidence in the relationship) and interference from partners (a disruption of partner routines that undermines goal attainment) to depressive symptoms and integration difficulties during post-deployment reunification. Another group of scientists reported that partner accommodation (alteration of one partner’s behaviors in response to the other partner’s PTSD symptoms) was associated with negative relationship satisfaction in couples (Fredman et al., 2014), but also positively contributed to treatment outcomes in couples-based therapy (Fredman et al., 2016).

Reciprocal Linkages Between Parent and Child Behaviors

Conceptualizing stress within the parenting or caregiving system informs an understanding not only of the importance of parenting for youth development and effective stress regulation, but also of the reciprocal linkages between parents and children. Effective caregiving or parenting is consistent, responsive, and sensitive and follows specific practices that vary according to the child’s developmental stage.

In early childhood, the development of a secure attachment relationship is a key developmental task and lays the foundation for healthy child development and effective stress regulation. In middle childhood and adolescence, key developmental tasks such as effective self-regulation, social skills, and academic skills are scaffolded by parents who show warmth, teach with encouragement, set clear and consistent limits, monitor and supervise, and model effective communication, problem-solving, and emotion-regulation skills. In later adolescence and young adulthood, as youth develop autonomy and their own identity, parents shift “off the stage and into the audience,” but research suggests that even in emerging adulthood authoritative parenting practices (i.e., high responsiveness with low control) are

associated with fewer mental health and substance use problems in these young adults (Nelson et al., 2011).

Reciprocal linkages between parent and child behaviors intersect with individual vulnerabilities, decreasing (or increasing) the risk for psychopathology across development. For example, in a 10-year prospective longitudinal study, Brody and colleagues (2017) demonstrated reciprocal linkages from early adolescence through emerging adulthood between youth temperament, harsh parenting, genetic vulnerability, and allostatic load (a physiological indicator of the cost of stress). Teacher ratings of difficult temperament in youth at age 11 were associated with subsequent youth-reported harsh parenting at age 15; this, in turn, was associated with allostatic load at age 21 (measured by blood pressure, body mass index, cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine). However, these associations were significant only for youth and parents who carried ‘risky’ A alleles on the oxytocin receptor (OXTR) genotype. Thus, vulnerability and protective processes at multiple levels (within and between family members) protect individuals from or render them less resilient to stress. These findings have relevance both to families in which service members are parents and to families in which the service members are emerging adults.

Patterson’s (1982, 2005) social interaction learning model offers a conceptualization of how stress affects parenting practices. Stressed parents demonstrate higher rates of coercive interactions with their children, such as escalation, aversive behaviors, negative reciprocity, and negative reinforcement. Escalating conflict bouts occur that are “won” or “lost” through aversive means, such as yelling, threatening, or harsh corporal punishment. When these social interactions become the norm rather than the exception, children learn that coercion pays off and replicate coercive behaviors in the home, school, and with peers. Both experimental and passive longitudinal studies demonstrated that high rates of coercive parent-child interactions increase the risk of child maltreatment and predict an increased risk of subsequent internalizing and externalizing behaviors that extends into adulthood (Capaldi et al., 2003; Patterson et al., 1998). Fortunately, evidence-based interventions that teach effective, positive parenting behaviors reduce coercion and the risk of maltreatment and improve child adjustment and resilience (Forgatch and Gewirtz, 2017).

Walsh (1996, 2016) introduced and elaborated on naturally occurring and protective family-level resilience processes that support well-being, but that are also vulnerable to the effects of stress. The resilience processes they studied include “organizational patterns, communication and problem-solving processes, community resources, and affirming belief systems” (Walsh, 1996, p. 261). Saltzman and colleagues (2011) adapted these same principles to military families, shifting focus from identification of specific risk and resilience factors to a broad conceptualization of risk

mechanisms that can undermine military family well-being when faced with stress. The latter authors highlighted five mechanisms that can undermine resilience in military families—namely, incomplete understanding [of military-related experiences or outcomes], impaired family communication, impaired parenting, impaired family organization, and lack of guiding belief systems—each of which can undermine health-promoting/normative family processes resulting in potential negative family outcomes. (For full description of mechanisms of risk, see Saltzman et al. [2011, p. 217, Table 1]). As a result, normative family resilience processes that are negatively impacted by military family stress can serve as points of intervention for family-centered programs designed to support well-being.

Although distinct from military family stress, disaster-related family stress shares similar family effects, and the more extensive scientific literature in this area further informs our understanding of the impact of military-related stress on family resilience processes. For example, Noffsinger and colleagues (2012) highlighted the effects of disaster-related stress on the structure, roles, boundaries, and functions (e.g., flexibility, adaptability, communication, decision making, and problem solving) within families. In turn, family mechanisms, such as family cohesion (Laor et al., 2001), family conflict (Gil-Rivas et al., 2004; Wasserstein and La Greca, 1998) and parental overprotectiveness (Bokszczanin, 2008) have all been associated with post-disaster outcomes, suggesting reciprocal mechanisms by which stress and family-level processes affect family well-being. These findings are instructive to our understanding of military families and point to additional targets of engagement for family-centered interventions to promote resilience and family well-being.

THE EFFECTS OF HIGH-STRESS EVENTS ON MILITARY FAMILIES: DUTY-RELATED ILLNESS, INJURY, AND DEATH, MILITARY FAMILY VIOLENCE, AND CHILD MALTREATMENT

As mentioned earlier, military families are affected by a range of experiences that can add both challenges and opportunities to their lives (see Chapter 4). However, certain high-stress events are more likely to be associated with negative effects within families, and this section focuses on those highly stressful experiences that have been most studied. For example, physical injury and psychological traumatic stress are important examples of defining events that can complicate a military family’s well-being, lead to problems within the family, affect the functioning of marital and parenting relationships and, in turn, undermine the individual and collective well-being of adults and children. In this section, we provide examples of the potentially undermining effects of the following heightened stressors on military family well-being: service-related mental health conditions and injuries incurred in the line of duty, military-duty-related deaths, military family violence, and child maltreatment.

PTSD, Major Depressive Disorder, and Other Duty-Related Mental Health Conditions

Upon return from combat in Iraq and Afghanistan, 19 percent of service members reported symptoms consistent with the presence of a psychiatric disorder, including PTSD, depression, anxiety disorder, and substance abuse (Hoge et al., 2006). While a comprehensive review of the prevalence of mental health conditions identified that “most service members return home from war without problems and readjust successfully,” that same review also found that “some have significant deployment-related mental health problems” (Tanielian and Jaycox, 2008, p. 433). Prevalence of PTSD and major depression among Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) veterans was estimated to be 5 to 15 percent and 2 to 14 percent, respectively. Unfortunately, of those with probable disorders, only half were estimated to have sought help from a health care professional (Tanielian and Jaycox, 2008).

Consequently, of the 2.7 million service members who have been deployed to war zones in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2001, between 100,000 and 400,000 combat veterans have likely been affected by these disorders. Adding to these health concerns, both PTSD and major depressive disorder are known to have numerous long-term and negative effects, including functional impairment, poor physical health, neuropsychological damage, risk of comorbid substance use, and elevated risk of death among those affected (Hidalgo and Davidson, 2000; Kessler, 2000; Kessler et al., 2012).

PTSD

In addition to combat exposure, other stressors and traumatic events that occur as part of military duty may result in post-traumatic symptoms or an actual diagnosis of PTSD. For example, service members are frequently called upon in times of national or international crisis, disaster, or terrorism. In such circumstances, they may be required to function within a hostile community, serve as first responders, or otherwise be directly exposed to stressful or traumatic experiences that could put them at risk for traumatic stress responses. Body handling and other mortuary responsibilities have specifically been shown to increase risk for PTSD among military service personnel, especially in circumstances that involve exposure to gruesome human remains (Flynn et al., 2015; McCarroll et al., 1993, 1995).

In addition, a recent study describing data from the 2009-2011 National Health Study for a New Generation of U.S. Veterans (a population-based survey of 60,000 veterans who served during OEF/OIF) found that 41 percent of female and 4 percent of male veterans reported experiencing military sexual trauma, including sexual harassment and sexual assault (Barth et al., 2016), creating additional pathways of risk. PTSD is commonly associated with

military sexual trauma (Suris and Lind, 2008), adding to the mental health burden within the military community as well as among military families.

PTSD has been consistently associated with negative effects on relationships between service members and their spouses and children. Table 6-1 provides a diagrammatic summary of the effects of PTSD symptom clusters and their likely impact on familial resilience processes. Galovski and Lyons (2004) reviewed the effects of PTSD on intrafamilial relationships, describing the association of psychological symptoms and risk behaviors with poorer marital satisfaction, impaired family functioning, and greater family distress and violence. Studies of Vietnam veterans have described the relationship between PTSD and family violence (Jordan et al., 1992; Petrik et al., 1983). Other studies of combat veterans have found that the presence and severity of PTSD symptoms better account for veteran aggression than combat exposure alone (Hoge et al., 2006; Jakupcak et al., 2007; Sayers et al., 2009; Taft et al., 2007).

On a positive note, Elbogen and colleagues (2014) found that socioeconomic factors (money and stable employment), psychosocial factors (resilience, sense of control over one’s life, and social support) and physical factors (adequate sleep and lack of pain) all served as protective mechanisms to decrease community violence in veterans and could potentially diminish partner aggression as well.

Some investigators have examined the impact of PTSD on marital relationship processes and found that PTSD symptoms were associated with poorer communication, marital confidence, relationship dedication, parental alliance, and relationship bonding (Allen et al., 2010). In addition, PTSD has been associated with intimate partner discord and poorer intimate relationship satisfaction, with two studies showing avoidance and numbing

TABLE 6-1 Negative Effects of PTSD Symptom Clusters on Family Resilience Processes

| Re-experiencing | Avoidance | Negative Cognitions and Mood | Arousal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Closeness | – | – | – | – |

| Communication | – | – | ||

| Safety and Impulse Control | – | – | – | |

| Family Leadership | – | – | ||

| Family Hopefulness | – | – | ||

| Supervision of Children | – | |||

| Authoritative Discipline of Children | – | – | – |

SOURCE: Adapted from Cozza (2016).

NOTE: The minus sign indicates a negative effect.

associated with relationship dissatisfaction and hyperarousal2 associated with marital conflict or aggression and spousal abuse (Allen et al., 2018; Monson et al., 2009). Male service members’ higher experiential avoidance has been associated with poorer observed couple communication and lower perceived relationship quality in both service members and their spouses (Zamir et al., 2018). Spouses of chronically PTSD-affected service members report higher rates of distress, depression, suicidal ideation, and poorer adjustment than spouses of non-affected service members (Calhoun et al., 2002; Manguno-Mire et al., 2007).

Fredman and colleagues (2014) introduced the concept of partner accommodation, by which spouses appear to modify their own behavior or enable the avoidance of the PTSD-affected service member or veteran, further undermining relationships and partner health. Others have termed this process walking on eggshells (Snyder, 2013–2015). Recent work has summarized the effects of PTSD in affected couples, as well as outlined the importance of future research that could more broadly examine the impact of mediators and moderators on these effects, thereby suggesting additional targets of intervention (Campbell and Renshaw, 2018).

PTSD has similarly been shown to affect parenting satisfaction and parenting behaviors (Berz et al., 2008; Gewirtz et al., 2010; Samper et al., 2004), although based on observational data only mothers’ PTSD symptoms (not fathers’) has been found to influence couples’ parenting behaviors (Gewirtz et al., 2018a). Parenting can be impaired by greater emotional reactivity, loss of cognitive capacity, greater levels of interpersonal aggression, or the increased avoidance and disconnection from loved ones that is commonplace with PTSD. For example, experiential avoidance3 in National Guard service members moderated associations between PTSD and observed parenting behavior, such that only at high levels of avoidance were PTSD symptoms associated with impaired parenting behaviors (Brockman et al., 2016). In another report, couples’ observed parenting practices mediated the associations between mothers’ PTSD symptoms and poorer child adjustment, as well as the associations between couple adjustment and children’s behavioral and emotional symptoms (Gewirtz et al., 2018b).

___________________

2 Hyperarousal is defined by Merriam-Webster’s dictionary as “an abnormal state of increased responsiveness to stimuli that is marked by various physiological and psychological symptoms (such as increased levels of alertness and anxiety and elevated heart rate and respiration).” In addition, to be diagnosed with PTSD, “a person has to have been exposed to an extreme stressor or traumatic event to which he or she responded with fear, helplessness, or horror and to have three distinct types of symptoms consisting of reexperiencing of the event, avoidance of reminders of the event, and hyperarousal for at least one month.” (See https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/hyperarousal.)

3 Experiential avoidance is “the tendency to avoid internal, unwanted thoughts and feelings” (Kashdan et al., 2014, p. 1).

Clinical accounts describe the challenges faced by PTSD-affected couples when co-parenting (Allen et al., 2010); as a result, couples often need to renegotiate parenting responsibilities due to PTSD (Cozza, 2016).

Not unexpectedly, children are likely to be affected by the emotional and behavioral changes in a PTSD-affected parent, depending on the child’s age, developmental level, temperament, and any preexisting conditions. Children of Vietnam veterans with PTSD exhibit general distress, depression, low self-esteem, aggression, impaired social relationships, and school-related difficulties (Rosenheck and Nathan, 1985). PTSD can result in greater distress or worsening of symptoms in children with pre-existing medical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional conditions. Young children may have an especially hard time understanding and coping with the parental overreaction or disengagement that can result from PTSD. Of note, family violence resulting from PTSD can further undermine child health (Galovski and Lyons, 2004). In a longitudinal study of OEF/OIF reserve component families, Snyder and colleagues (2016) demonstrated reciprocal cascades among fathers’ and mothers’ PTSD symptoms and their children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

Depression and Substance Use Disorders

Although greater attention has been paid to the impact of PTSD on intrafamilial relationships within combat veteran families, depression is also known to have serious consequences for intrafamilial relationships and, like PTSD, has been shown to be a consequence of service members’ combat exposure (see Hoge et al., 2006; and Tanielian and Jaycox, 2008). Although studies within military samples are lacking, in the general population depressive disorders have been consistently associated with interpersonal negativity, communication difficulties, and interpersonal stress within affected couples and families (Gabriel, et al., 2010; Rehman et al., 2008). Not surprisingly, such effects also result in greater levels of marital dissatisfaction and discord. Relevant to military family well-being, parental depression is a known risk factor for depression and anxiety, behavioral problems, and academic and cognitive difficulties in their children (for a review, see Beardslee et al., 2011). Research examining the impact of parental depression within military families is required, especially since family-based interventions have been shown to successfully address these pathways of risk in clinical trials (Beardslee et al., 2003).

As with depressive disorders, for substance use disorders the intrafamilial effects have not been examined within military families, but studies of the general population show that they are clearly associated with marital distress (Whisman, 2007) as well as problematic parenting (Arria et al., 2012). Given that substance use disorders, like PTSD and

depression, have been associated with combat deployments (Shen et al., 2012), their effects are likely present among military families, yet they remain unstudied.

Effects of Service Member Physical Injuries on Families

More than 90 percent of service members who were injured in Iraq or Afghanistan in the first 4 years of conflict survived their injuries, a testament to advances in battlefield medicine and efficiency within the aeromedical evacuation system (Goldberg, 2007). Almost 30,000 service members were wounded in action during Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom combined (Goldberg, 2007). Describing combat wounds from 2001 to 2005, Owens and colleagues (2008) reported the following distribution by type of wound: 54 percent extremity, 11 percent abdominal, 11 percent head and neck, 10 percent facial, 6 percent thoracic, 6 percent eyes, and 3 percent ears. These injuries resulted in amputations, blindness, deafness, and other long-lasting functional impairments (Owens et al., 2008). In addition, the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center reports that since 2000 nearly 380,000 service members have been diagnosed with traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Defense Veterans Brain Injury Center, 2015). Although TBI may be a result of combat-related injuries, service members can also sustain such injuries from other duty-related events, such as training, operations, or deployment and from non-duty-related events, such as recreational events and motor vehicle accidents.

The burden to family members secondary to combat-related injury has been described elsewhere4 and often includes long and stressful rounds of treatment and rehabilitation as well as changes in functioning that can require family members to assume new roles within the family, such as caregiving. A family’s experience is likely to be determined by the type and severity of the injury, family composition, preexisting individual and family conditions, the ages of children, the course of required medical treatment, and whether the injured regains satisfactory functioning.

The course of recovery for the family of an injured military service member has been conceptualized as an injury recovery trajectory (Cozza and Guimond, 2011) consisting of four phases:

- Acute care, which is initiated at the time of injury by military medics and includes care provided in combat hospitals;

- Medical stabilization, which incorporates definitive medical treatment in U.S. stateside military medical centers;

___________________

4 For example, in Badr et al. (2011), Cozza (2016), Cozza and Feerick (2011), Cozza and Guimond (2011), Cozza et al. (2011), and Holmes et al. (2013).

- Transition to outpatient care, which often includes relocations of injured service members to treatment facilities closer to home, transition of treatment teams, and possible medical discharge from military service; and

- Long-term rehabilitation and recovery, which involves the ongoing care of the service member in order to maximize treatment benefits and long-term functioning.

During each phase, families face multiple emotional and logistical challenges. For example, during medical stabilization, military spouses and children often relocate to military treatment facilities to be closer to their injured loved ones. However, depending upon circumstances, individual family members may be geographically separated, disrupting daily routines and adding stress. Transition to outpatient care involves other stressors: finding new housing, working with new health care providers, enrolling children in new schools, and possibly leaving their military friends and communities behind. These effects are long and cascading.

Depending upon the nature of the physical injury, service members may have physical, psychological, or cognitive changes that affect functioning in a variety of areas of their lives, including parenting. When injuries result in major changes to the ways in which a service member traditionally parents (e.g., when a parent can no longer walk, run, or play), this may result in a sense of loss or mourning over body changes. Cozza and colleagues (2011) described how injured service members must modify a previously held, idealized sense of themselves as parents and may need to explore new ways of playing with their children so that they can continue to relate to them. Injuries and prolonged hospitalizations or rehabilitation can also lead to conflict with spouses that can undermine marital health (Kelley et al., 1997; LeClere and Kowalewski, 1994), as well as the ability to effectively co-parent.

Effects of Traumatic Brain Injury

The neuropsychiatric consequences of TBI, including personality changes, loss of control, unexpected emotional reactions, irritability, anger, and apathy or lack of energy can be particularly problematic to interpersonal relationships (Weinstein et al., 1995). In fact, such symptoms are more distressing to family members and disruptive to family functioning than other, non-neurological physical injuries (Urbach and Culbert, 1991). In a study of nonmilitary families by Pessar and colleagues (1993), noninjured parents reported increased externalizing behaviors, as well as emotional and post-traumatic symptoms, in their children after the parental TBI. In addition, TBI correlated with compromised parenting in both injured and noninjured parents and with depression in the non-TBI parent

(Pessar et al., 1993). Children of TBI-affected parents have described feelings of loss (Butera-Prinzi and Perlesz, 2004), as well as isolation and loneliness (Charles et al., 2007), after the TBI incident. Factors that have all been associated with child outcomes include the severity of TBI symptoms, the amount of time since injury, child age and gender, preinjury family functioning, and postinjury disruptions of family organization and structure (Urbach and Culbert, 1991; Verhaeghe et al., 2005).

Given sustained neuropsychiatric impairment, TBI is likely to have a long-term impact on military families. Young families with poorer financial and social support appear to be at the greatest risk for negative outcomes (Verhaeghe et al., 2005). Financial, housing, social assistance, employment support and access to professional service are critical to the well-being of families facing the long-term effects of a TBI injury (Verhaeghe et al., 2005).

Effects on Family Caregivers

Physical and mental injuries from nearly two decades of war since 9/11 have impacted service members and veterans who rely upon family caregiving that secondarily impacts family well-being (Ramchand et al., 2014). Results of this recent RAND study indicate that there are 5.5 million military caregivers in the United States. Military caregivers are the informal network of family members, friends, or acquaintances who devote a great deal of time caring for impacted service members and veterans. Military caregivers are more likely to be nonwhite, a military veteran, and younger. They may be required to provide decades of future care for young disabled service members and older veterans and who, themselves, are less likely to be connected to support networks and describe poorer levels of personal physical health (Ramchand et al., 2014). Caregiving is provided while they attempt to maintain ongoing employment that does not uniformly support their need for flexibility. No systematic studies have examined these effects on military family well-being.

Although some medically derived interventions to support the health of military families faced with combat-related injuries or illness have been described (Smith et al., 2013), most medical systems remain committed to patient-centered rather than family-centered models of care. Not surprisingly, health care environments are often either unsuited to or unprepared for addressing these complex effects within military families.

Effects of Military-Duty-Related Death on Families and Children

Within the decade after September 11, 2001, nearly 16,000 military service members died while on active duty. These deaths were due to accidents (34%), combat (32%), suicides (15%), illnesses (15%), homicides (3%),

and terrorism (less than 1%) (Cozza et al., 2017). These deceased service members left behind 9,667 dependent widowed spouses and 12,641 young dependent children whose mean age was 10.3 years (Cozza et al., 2017), as well as a difficult-to-determine number of extended relatives including parents, siblings, and cousins. A recent study examining grief responses, which examined a community sample of 1,732 first-degree family members of deceased military service members, found that 15 percent of participants reported elevated levels of grief and associated functional impairment that was consistent with a clinical disorder of impairing grief (Cozza et al., 2016). This finding should not be surprising, given that 85 percent of deaths related to military duty are sudden and violent (Cozza et al., 2016), creating greater risk for negative grief-related outcomes (Kristensen et al., 2012).

Widowed military spouses tend to be young, and many have not had the opportunity to pursue their own individual careers due to frequent moves and other requirements of military family life. Until the time of their spouses’ deaths, they and their families will have lived within military communities and among other military families, accessing resources available within these communities. However, after the death of their military spouses, widowed spouses experience sudden and unanticipated transitions to life outside of the military community among civilians who often do not fully appreciate their history or their culture (Harrington-Lamorie et al., 2014). Military widows/widowers are also subject to rules that can adversely affect them if they choose to remarry. For example, if a bereaved military spouse chooses to remarry before age 55, he or she loses access to the Survivor Benefit Plan and other military-related benefits that are received after widowhood. Given the young age of bereaved military spouses, such rules can make it difficult for military widows and widowers to fully invest in their future lives (Cozza et al., 2019).

The death of a parent, particularly for young children, has been associated with anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress symptoms (Currier et al., 2007; Finkelstein, 1988; Reinherz et al., 2000). The loss of a parent may also lead to transitions in residence for military families, changes to financial stability, and challenges to parenting due to the resultant grief of any surviving caregiver, which can disrupt child care. In the aftermath of parental death, poorer child outcomes have been associated with poorer adult caregiver outcomes, further highlighting the linked lives within military families and potential vulnerabilities to children following parental death (Saldinger et al., 2004).

Rates of suicide have risen within the U.S. military since 2004, both among those never deployed and among prior-deployed service members (Schoenbaum et al., 2014). Suicide accounted for nearly 15 percent of military service deaths in the decade after 9/11 (Cozza et al., 2017). Suicide is a unique form of death, but like other forms of sudden and violent death it increases risk for negative grief outcomes in those who are affected

(Kristensen et al., 2012). Notably, suicide is more likely to be associated with guilt and stigmatization within families compared to other types of death (Feigelman et al., 2009), which can harm family well-being. Despite these concerns, parental suicide has not been shown to have more negative effects on children than other violent or nonviolent parental deaths (Brown et al., 2007; Cerel et al., 2000; Pfeffer et al., 2000). Historically, military suicides have not infrequently been attributed to service member misconduct or been determined to be “not within the line of duty,” which can further stigmatization and result in loss of benefits to military family members. Recent efforts have attempted to reverse this practice.

Family Violence and Child Maltreatment

Family maltreatment includes physical, sexual, or emotional aggression or neglect within a family, either between adult partners (spousal abuse or intimate partner violence), between parents and children (child maltreatment), or among multiple family members (e.g., domestic violence). Any form of family maltreatment creates stressful challenges within a family, but in addition it represents maladaptive responses that undermine family well-being. In addition to posing risks to military family well-being, it poses a serious public health risk to military communities. The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has developed substantive prevention efforts through the Family Advocacy Program (FAP), at both DoD and military service levels. For families where maltreatment has occurred, activities in this program engage at-risk families (e.g., New Parent Support Program), identify episodes of family maltreatment (e.g., case identification), and monitor, support, and provide intervention (e.g., FAP case management).

Few studies compare rates of family maltreatment between military and civilian populations, and those that have must be cautiously interpreted due to small sample sizes and methodological limitations, including use of nonrepresentative samples. Combat deployments have been associated with small but significant increases in intimate partner violence in at least three reports (McCarroll et al., 2000, 2003; Newby et al., 2005). Additionally, depression, substance use disorders, and PTSD have each been associated with elevated levels of intimate partner violence in both active duty service members as well as veterans (Sparrow et al., 2017). In fiscal year 2017, data from the Office of the Secretary of Defense Family Advocacy Program’s Central Registry, which aggregates data from each military service, indicates that the rate of reported spouse abuse per 1,000 couples was 24.5, which is a non-statistically significant 5 percent increase in the rate of reported incidents since 2016 (DoD, 2018).

Lower rates of child maltreatment have been reported in military communities as compared to civilian communities (DoD, 2018; McCarroll et

al., 2003), although because these comparisons are based on the number of substantiated maltreatment cases they might not indicate actual differences in the underlying risk across communities. Regardless, child maltreatment remains a challenge to military communities and to military family wellbeing. In fiscal year 2017, there were 12,849 reports of suspected child abuse and neglect to the Family Advocacy Program (DoD, 2018).

Notably, child neglect comprises the most common form of family maltreatment in both military and civilian communities. Child neglect involves an act “in which a child is deprived of needed age-appropriate care by act or omission of the child’s parent, guardian, or caregiver” (Fullerton et al., 2011, p. 1433). Elevated rates of military child neglect have been associated with combat activities in Iraq and Afghanistan (Gibbs et al., 2007; McCarroll et al., 2008; Rentz et al., 2007) and have continued to rise within military communities through 2014, adding concern about military family well-being even as combat deployments have decreased. Various types of child neglect—failure to provide physical needs, lack of supervision, emotional neglect—have been variably associated with deployment status (Cozza et al., 2018b) and family risk factors (Cozza et al., 2018a) in military samples, suggesting the need for tailored prevention and policy efforts.

Military family violence and child maltreatment serve as examples of maladaptive responses within highly reactive families or those that are unskilled in responding to the challenges with which they are faced. In each of the service branches, FAP currently offers the New Parent Support Program, which targets vulnerable families, including young families with newborn infants and or those challenged by deployments, mental health or substance use problems, medical or developmental disorders, or prior history of maltreatment or family violence. FAP also offers counseling for parents to discontinue harmful behaviors, manage anger, and promote positive parenting practices. Although some evaluation of existing DoD programs is underway, its scope is limited and should incorporate recommended strategies (see Chapters 7 and 8) to ensure that provided services reflect the needs of targeted populations.

Contextual Moderators

The effects of stress on families must be contextualized within preexisting levels of individual and family functioning and among multiple experiences, including prior traumas, adverse childhood experiences, acute and chronic stressors, and microaggressions. In addition, the effects of stress need to be considered within the developmental context of the family and its individual members. For example, stresses affect service members and families within the changing context of new marriages, divorces, births of

children, changing medical, neurodevelopmental or educational conditions among family members, new or lost employment of military spouses, transitions from military life, or changes in extended family obligations, such as unexpected child care requirements or new responsibilities associated with aging parents. Notably, and in addition to the impact of duty-related stressors, military family well-being is likely affected by individuals’ prior traumatic experiences, pre-existing mental health conditions (including personality disorders), and prior adverse childhood experiences, which have been associated with new-onset depression among service members in at least one study (Rudenstine et al., 2015).

Other factors, or contextual moderators, are likely to affect the associations between military-related adversities and family and child health and well-being. For example, families with a member on National Guard or Reserve status remain understudied. Effects on nontraditional families (including single-parent families, female service member families, dual-military families, sexual minority families, and immigrant families); families having low socioeconomic status; racial, ethnic, and religious considerations; and Exceptional Family Member Program families faced with medical or neurodevelopmental conditions have also not been examined. The greater stigmatization that families in some of those categories experience, as well as the fewer inherent resources some of them can access, their increased need for services, and their reduced access to community support are likely to add vulnerability in the face of military adversities. Community service and health care providers are less likely to be aware of and educated about the needs within these subpopulations, making it more difficult to address their needs.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR BOLSTERING RESILIENCE BY ADDRESSING RISK PATHWAYS

Of relevance to military service systems are consistent findings that the effects of severe stressors can be prevented and ameliorated with evidence-based interventions focused on strengthening the caregiving, parenting, and family environment. The risk processes that characterize the military family stresses described above can be conceptualized both as individual processes and as linked (family) processes. For example, child abuse and neglect result from ineffective regulation and skills in parental emotion and behavior, leading to an inability to inhibit physically aggressive responses to stress, poor parenting skills, preoccupation secondary to depression or substance abuse leading to neglect, impaired judgement due to cognitive limitations, and/or lack of child development knowledge. Targeting these key cognitive, emotional, and behavioral processes in parents by providing them guidance about child development, emotion regulation, and parenting skills such as effective discipline, warmth, and

encouragement, reduces and prevents child maltreatment (Olds et al., 1997; Prinz, 2016). Domestic violence, which greatly overlaps child maltreatment, is associated with similar processes, that is, with cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dysregulation that is manifested in problems such as couples’ poor problem solving and poor conflict resolution.

Not surprisingly, family-based prevention programs targeting these and related risk events have similar components. They are found to have generalized effects, sometimes called “crossover effects,” in benefiting not simply the intervention target (parenting, the couple relationship, and/or child adjustment and development) but the entire family system through cascading positive effects that occur over time. Thus, for example, evidence-based parenting programs not only improve parenting practices but also strengthen child adjustment and parental well-being, as well as reducing PTSD, depression symptoms, and suicidality (Gewirtz et al., 2016, 2018a).

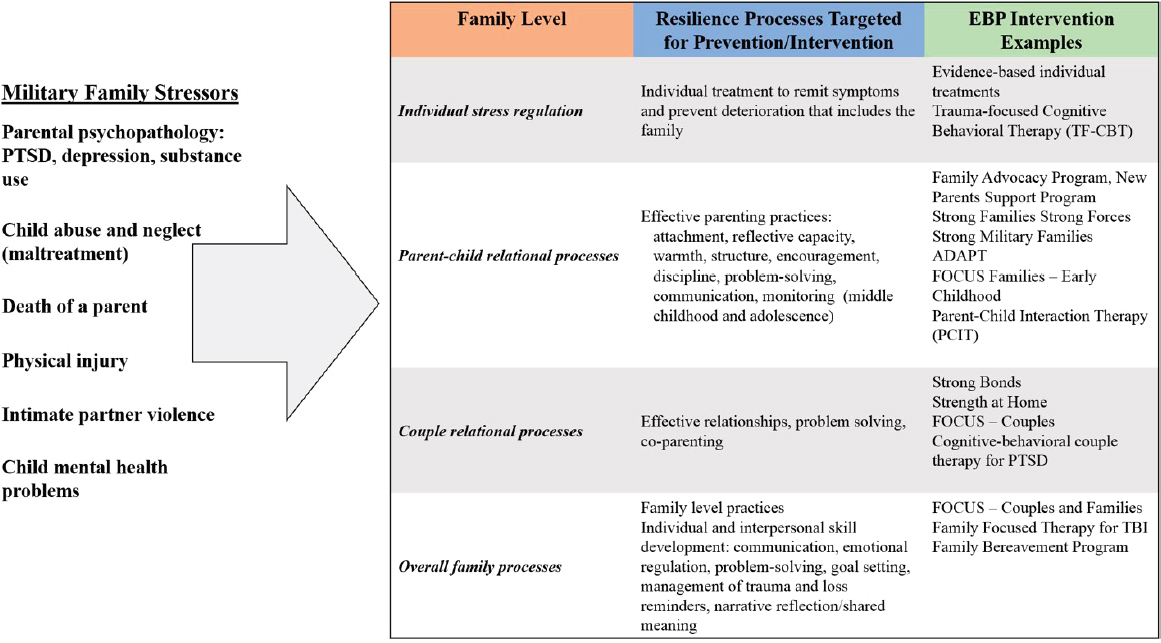

Figure 6-1 depicts targets for interventions at different levels within the family to promote resilience processes in order to support overall family well-being. The figure also provides examples of evidence-based interventions targeting individual, couple, parenting, and family-level processes. Several evidence-based military family intervention programs, which have been evaluated with randomized controlled trials, have relevance to families affected by such adversities.

Many of these programs have been developed and tested within the Department of Defense, including the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program, and/or with research funding from the National Institutes of Health. Examples include programs targeting individual stress response, such as the Trauma Focused-Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) (Cohen et al., 2012); programs targeting parenting for families with very young children, such as Strong Families Strong Forces (DeVoe et al., 2017) and Strong Military Families (Julian et al., 2018); programs targeting school-age children, such as After Deployment, Adaptive Parenting Tools/ADAPT (Gewirtz et al., 2018a); and programs targeting parenting, parent-child relationships, and family communication more broadly, such as Families OverComing Under Stress/FOCUS (Lester et al., 2013), as well as programs targeting couple functioning in particular, such as Strong Bonds (Allen et al., 2015) and Strength at Home (Taft et al., 2016). These programs are designed to support families affected by deployment and other duty-related risks through strengths-based approaches that focus on improving couple, family, and parent-child relationships by fostering family resilience processes such as such as emotion regulation, communication, problem solving, and the elements of positive parenting delineated above.

Other family-centered programs have addressed the challenges of TBI and family bereavement. For example, two programs that have been developed to support families affected by TBI—Family Focused Therapy for TBI

(FFT-TBI) (Dausch and Saliman, 2009) and Brain Injury Family Intervention (BIF) (Kreutzer et al., 2010)—share similar strategies to educate affected family members about TBI and improve communication within the family, as well as encourage problem solving, stress management, and family goal setting. The Family Bereavement Program (FBP) is a multimodal intervention that similarly incorporates positive parenting strategies as well as individual and relationship strengthening activities to support bereaved families (Sandler et al., 2003).

The examples provided above do not constitute an exhaustive list of family resources for military families, but instead are offered to highlight evidence-based programs that have been rigorously evaluated in a military context, as reviewed in Chapter 7. In contrast, while other military family programs may target the risk factors highlighted above, most have not yet been rigorously evaluated to determine whether they actually achieve their intended aims. In fact, all existing family programs should be evaluated (as described in Chapters 7 and 8) to ensure that they are meeting their intended goals within the context of a coherent Military Family Readiness System (as described in Chapters 7 and 8), and new programs should only be developed when unmet needs are identified as part of a process of continuous program evaluation.

Family strengthening programs are critical to a public health approach to supporting wellness at universal, selective, and indicated levels. At the universal and selective levels, family-centered prevention programs offer an opportunity to increase resilience processes, thereby reducing risk. At indicated levels, clinicians and other community support providers are obligated to identify individuals who demonstrate symptoms consistent with clinical disorders and to transition them to evidence-based treatments when indicated. Figure 6-1 provides a depiction of the impact of military family stressors at different levels within the family, and examples of EBP interventions. Although these evidence-based interventions differ in format, content, and emphasis, all share several essential family-strengthening goals, as listed in Box 6-1.

CONCLUSIONS

CONCLUSION 6-1: Military families can be adversely affected by some aspects of military life, such as deployments, illnesses, and injuries, due to their undermining of healthy intra-familial resilience processes that support family well-being and readiness. Family resilience processes (e.g., effective communication strategies, emotion regulation, problem solving, and competent parenting) serve as opportunities for promotion, prevention, and intervention in the wake of stress and trauma.

CONCLUSION 6-2: The effects of duty-related stress on families are likely to be modified by family members’ prior traumas, medical or

mental health conditions, and acute or chronic family stressors, as well as by other contextual factors such as service component and single-parent or socioeconomic status.

CONCLUSION 6-3: Similar to maltreatment in civilian families, military family violence and child maltreatment indicate maladaptive responses within highly reactive families or those that are unskilled in responding to the challenges with which they are faced. Given adverse outcomes associated with family maltreatment, broadened evaluation efforts are required to examine the effectiveness of existing programs in this area.

CONCLUSION 6-4: Most health care settings are not prepared to deal with family circumstances associated with duty-related injury or illness, and would therefore benefit by being complemented with nonmedical approaches to better support family well-being.

CONCLUSION 6-5: Evidence-based programs, resources, and practices have been developed and evaluated for highly impacted military families that support normative individual and family-based resilience processes, well-being, and readiness; however, these interventions are not widely implemented in routine military family settings.

REFERENCES

Allen, E. S., Knopp, K., Rhoades, G., Stanley, S., and Markman, H. (2018). Between- and within-subject associations of PTSD symptom clusters and marital functioning in military couples. Journal of Family Psychology 32, 134–144.

Allen, E. S., Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., and Markman, H. J. (2010). Hitting home: Relationships between recent deployment, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and marital functioning for Army couples. Journal of Family Psychology 24, 280.

Allen, E. S., Stanley, S., Rhoades, G., and Markman, H. (2015). PREP for Strong Bonds: A review of outcomes from a randomized clinical trial. Contemporary Family Therapy, 37(3), 232–246.

Arria, A. M., Mericle, A. A., Meyers, K., and Winters, K. C. (2012). Parental substance use impairment, parenting and substance use disorder risk. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 43(1), 114–122.

Badr, H., Barker, T. M., and Milbury, K. (2011). Couples’ psychosocial adaptation to combat wounds and injuries. In S. MacDermid Wadsworth and D. Riggs (Eds.), Risk and Resilience in U.S. Military Families (pp. 213–234). New York: Springer Science and Business Media.

Barth, S. K., Kimerling, R. E., Pavao, J., McCutcheon, S. J., Batten, S. V., Dursa, E., Peterson, M. R. and Schneiderman, A. I. (2016). Military sexual trauma among recent veterans: correlates of sexual assault and sexual harassment. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 50, 77–86.

Beardslee, W. R., Gladstone, T. R., and O’Connor, E. E. (2011). Transmission and prevention of mood disorders among children of affectively ill parents: A review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 50(11), 1098–1109.

Beardslee, W. R., Gladstone, T. R., Wright, E. J., and Cooper, A. B. (2003). A family-based approach to the prevention of depressive symptoms in children at risk: Evidence of parental and child change. Pediatrics 112(2), e119–e131.

Berz, J. B., Taft, C. T., Watkins, L. E., and Monson, C. M. (2008). Associations between PTSD symptoms and parenting satisfaction in a female veteran sample. Journal of Psychological Trauma 7, 37–45.

Bodenmann, G. (1997). Dyadic coping-a systematic-transactional view of stress and coping among couples: Theory and empirical findings. European Review of Applied Psychology 47, 137–140.

Bokszczanin, A. (2008). Parental support, family conflict, and overprotectiveness: predicting PTSD symptom levels of adolescents 28 months after a natural disaster. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping 21, 325–335.

Brockman, C., Snyder, J., Gewirtz, A., Gird, S.R., Quattlebaum, J., Schmidt, N., Pauldine, M.R., Elish, K., Schrepferman, L., Hayes, C. and Zettle, R. (2016). Relationship of service members’ deployment trauma, PTSD symptoms, and experiential avoidance to postdeployment family reengagement. Journal of Family Psychology 30(1), 52–62.

Brody, G. H., Yu, T., Barton, A. W., Miller, G. E., and Chen, E. (2017). Youth temperament, harsh parenting, and variation in the oxytocin receptor gene forecast allostatic load during emerging adulthood. Development and Psychopathology 29, 791–803.

Bronfenbrenner, U., and Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In W. Damon, and R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology (vol. 3, pp. 793–828). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Brown, A. C., Sandler, I. N., Tein, J. Y., Liu, X., and Haine, R. A. (2007). Implications of parental suicide and violent death for promotion of resilience of parentally-bereaved children. Death Studies 31(4), 301–335.

Butera-Prinzi, F., and Perlesz, A. (2004). Through children’s eyes: Children’s experience of living with a parent with an acquired brain injury. Brain Injury 18, 83–101.

Calhoun, P. S., Beckham, J. C., and Bosworth, H. B. (2002). Caregiver burden and psychological distress in partners of veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress 15, 205–212.

Campbell, S.B., and Renshaw, K. D. (2018). Posttraumatic stress disorder and relationship functioning: A comprehensive review and organizational framework. Clinical Psychology Review, 65, 152-162.

Capaldi, D. M., Pears, K. C., Patterson, G. R., and Owen, L. D. (2003). Continuity of parenting practices across generations in an at-risk sample: A prospective comparison of direct and mediated associations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 31, 127–142.

Cerel, J., Fristad, M. A., Weller, E. B., and Weller, R. A. (2000). Suicide-bereaved children and adolescents: II. Parental and family functioning. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39(4), 437–444.

Charles, N., Butera-Prinzi, F., and Perlesz, A. (2007). Families living with acquired brain injury: A multiple family group experience. NeuroRehabilitation 22, 61–76.

Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., and Deblinger, E. (Eds.). (2012). Trauma-Focused CBT for Children and Adolescents: Treatment Applications. New York: Guilford Press.

Conger, R. D., Wallace, L. E., Sun, Y., Simons, R. L., McLoyd, V. C., and Brody, G. H. (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology 38, 179–193.

Cozza, S. J. (2016). Parenting in military families faced with combat-related injury, illness, or death. In A. H. Gewirtz and A. M. Youssef (Eds.), Parenting and Children’s Resilience in Military Families (pp. 151–173). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International.

Cozza, S. J., Chun, R. S., and Miller, C. (2011). The children and families of combat-injured service members. In Walter Reed Army Medical Center Borden Institute, Combat and Operational Behavioral Health (pp. 503–534). Washington, DC: Department of the Army, The Borden Institute.

Cozza, S. J., and Feerick, M. M. (2011). The impact of parental combat injury on young military children. In J. D. Osofsky (Ed.), Clinical Work with Traumatized Young Children (pp. 139–154). New York: Guilford Press.

Cozza, S. J., Fisher, J. E., Mauro, C., Zhou, J., Ortiz, C. D., Skritskaya, N., Wall, M. M., Fullerton, C. S., Ursano, R. J., and Shear, M. K. (2016). Performance of DSM-5 persistent complex bereavement disorder criteria in a community sample of bereaved military family members. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(9), 919–929.

Cozza, S. J., Fisher, J. E., Zhou, J., Harrington-LaMorie, J., La Flair, L., Fullerton, C. S., and Ursano, R. J. (2017). Bereaved military dependent spouses and children: Those left behind in a decade of war (2001–2011). Military Medicine 182, e1684–e1690.

Cozza, S. J., and Guimond, J. M. (2011). Working with combat-injured families through the recovery trajectory. In S. MacDermid Wadsworth and D. Riggs (Eds.), Risk and Resilience in U.S. Military Families (pp. 259–277). New York: Springer Science and Business Media.

Cozza, S. J., Harrington-Lamorie, J., and Fisher J. E. (2019). U.S. military service deaths: Bereavement in surviving families. In American Military Life in the 21st Century: Social, Cultural, Economic Issues and Trends. Santa Barbara: Praeger/ABC-CLIO.

Cozza, C. S. J., and Lerner, R. M. (2013). Military children and families: Introducing the issue. The Future of Children, 23, 3–11.

Cozza, S. J., Ogle, C. M., Fisher, J. E., Zhou, J., Whaley, G. L., Fullerton, C. S., and Ursano, R. J. (2018a). Associations between family risk factors and child neglect types in U.S. Army communities. Child Maltreatment, 24(1), 98–106.

Cozza, S. J., Whaley, G. L., Fisher, J. E., Zhou, J., Ortiz, C. D., McCarroll, J. E., Fullerton, C. S. and Ursano, R. J. (2018b). Deployment status and child neglect types in the U.S. Army. Child Maltreatment 23(1), 25–33.

Currier, J. M., Holland, J. M., and Neimeyer, R. A. (2007). The effectiveness of bereavement interventions with children: A meta-analytic review of controlled outcome research. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36, 253–259.

Dausch, B. M., and Saliman, S. (2009). Use of family focused therapy in rehabilitation for veterans with traumatic brain injury. Rehabilitation Psychology 54, 279–287.

Defense Veterans Brain Injury Center. (2015). DoD Worldwide Numbers for TBI. Retrieved from http://dvbic.dcoe.mil/dod-worldwide-numbers-tbi.

DeVoe, E. R., Paris, R., Emmert-Aronson, B., Ross, A., and Acker, M. (2017). A randomized clinical trial of a postdeployment parenting intervention for service members and their families with very young children. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 9(Suppl 1), 25–34.

Elbogen, E. B., Johnson, S. C., Wagner, H. R., Sullivan, C., Taft, C. T., and Beckham, J. C. (2014). Violent behaviour and post-traumatic stress disorder in U.S. Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. British Journal of Psychiatry 204, 368–375.

Elder, G. H., Caspi, A., and Downey, G. (1986). Problem behavior and family relationships: Life course and intergenerational themes. Human Development and the Life Course: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 293–340.

Feigelman, W., Gorman, B. S., and Jordan, J. R. (2009). Stigmatization and suicide bereavement. Death Studies, 33(7), 591–608.

Finkelstein, H. (1988). The long-term effects of early parent death: A review. Journal of Clinical Psychology 44, 3–9.

Flynn, B. W., McCarroll, J. E., and Biggs, Q. M. (2015). Stress and resilience in military mortuary workers: Care of the dead from battlefield to home. Death Studies 39, 92–98.

Forgatch, M. S., and Gewirtz, A. H. (2017). The evolution of the Oregon model of parent management training. In J. Weisz and A. Kazdin (Eds.), Evidence-based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents Third Edition (pp. 85–102). New York: The Guilford Press.

Fredman, S. J., Pukay-Martin, N. D., Macdonald, A., Wagner, A. C., Vorstenbosch, V., and Monson, C. M. (2016). Partner accommodation moderates treatment outcomes for couple therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 84 79–87.

Fredman, S. J., Vorstenbosch, V., Wagner, A. C., Macdonald, A., and Monson, C. M. (2014). Partner accommodation in posttraumatic stress disorder: Initial testing of the Significant Others’ Responses to Trauma Scale (SORTS). Journal of Anxiety Disorders 28, 372–381.

Fullerton, C. S., McCarroll, J. E., Feerick, M., McKibben, J., Cozza, S., Ursano, R. J., and Child Neglect Workgroup. (2011). Child neglect in army families: A public health perspective. Military Medicine, 176(12), 1432–1439.

Gabriel, B., Beach, S. R., and Bodenmann, G. (2010). Depression, marital satisfaction and communication in couples: Investigating gender differences. Behavior Therapy 41(3), 306–316.

Galovski, T., and Lyons, J. A. (2004). Psychological sequelae of combat violence: A review of the impact of PTSD on the veteran’s family and possible interventions. Aggression and Violent Behavior 9, 477–501.

Gewirtz, A. H., Degarmo, D. S., and Zamir, O. (2016). Effects of a military parenting program on parental distress and suicidal ideation: After deployment adaptive parenting tools. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 46 (Supp. 1), S23–S31.

________. (2018a). After deployment, adaptive parenting tools: 1-year outcomes of an evidence-based parenting program for military families following deployment. Prevention Science 19, 589–599.

________. (2018b). Testing a military family stress model. Family Process 57, 415–431.

Gewirtz, A. H., Polusny, M. A., DeGarmo, D. S., Khaylis, A., and Erbes, C. R. (2010). Posttraumatic stress symptoms among National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq: Associations with parenting behaviors and couple adjustment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 78, 599–610.

Gibbs, D. A., Martin, S. L., Kupper, L. L., and Johnson, R. E. (2007). Child maltreatment in enlisted soldiers’ families during combat-related deployments. Journal of the American Medical Association 298(5), 528–535.

Gil-Rivas, V., Holman, E. A., and Silver, R. C. (2004). Adolescent vulnerability following the September 11th terrorist attacks: A study of parents and their children. Applied Developmental Science 8, 130–142.

Goldberg, M. S. (2007). Projecting the Costs to Care for Veterans of U.S. Military Operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Washington DC: Congressional Budget Office. Retrieved from http://www.dtic.mil/docs/citations/ADA473294.

Harrington-Lamorie J., Cohen J., Cozza S. J. (2014). Caring for bereaved military family members. In S. J. Cozza, M. N. Goldenberg, and R. J. Ursano (Eds.), Care of Military Service Members, Veterans and Their Families. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Hidalgo, R. B., and Davidson, J. R. (2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder: Epidemiology and health-related considerations. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61 (Supp. 7), 5–13.

Hoge, C. W., Auchterlonie, J. L., and Milliken, C. S. (2006). Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. Journal of the American Medical Association 295, 1023–1032.

Holmes, A. K., Rauch, P. K., and Cozza, S. J. (2013). When a parent is injured or killed in combat. The Future of Children, 23, 143–162.

Jakupcak, M., Conybeare, D., Phelps, L., Hunt, S., Holmes, H. A., Felker, B., . . . McFall, M. E. (2007). Anger, hostility, and aggression among Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans reporting PTSD and subthreshold PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20, 945–954.

Jordan, B. K., Marmar, C. R., Fairbank, J. A., Schlenger, W. E., Kulka, R. A., Hough, R. L., and Weiss, D. S. (1992). Problems in families of male Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 916–926.

Julian, M. M., Muzik, M., Kees, M., Valenstein, M., and Rosenblum, K. L. (2018). Strong military families intervention enhances parenting reflectivity and representations in families with young children. Infant Mental Health Journal, 39, 106–118.

Kashdan, T. B., Goodman, F. R., Machell, K. A., Kleiman, E. M., Monfort, S. S., Ciarrochi, J., and Nezlek, J. B. (2014). A contextual approach to experiential avoidance and social anxiety: Evidence from an experimental interaction and daily interactions of people with social anxiety disorder. Emotion, 14(4), 769–781.

Kelley, S. D. M., Sikka, A., and Venkatesan, S. (1997). A review of research on parental disability: Implications for research and counseling practice. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 41(2), 105–121.

Kessler, R. C. (2000). Post-traumatic stress disorder: The burden to the individual and to society. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61 (Supp. 5), 4–12; discussion 13–14.

Kessler, R. C., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., and Wittchen, H.-U. (2012). Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 21, 169–184.

Knobloch, L. K., Ebata, A. T., McGlaughlin, P. C., and Ogolsky, B. (2013). Depressive symptoms, relational turbulence, and the reintegration difficulty of military couples following wartime deployment. Health Communication, 28, 754–766.

Knobloch, L. K., and Theiss, J. A. (2011). Depressive symptoms and mechanisms of relational turbulence as predictors of relationship satisfaction among returning service members. Journal of Family Psychology, 25, 470–478.

Kreutzer, J. S., Stejskal, T. M., Godwin, E. E., Powell, V. D., and Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. (2010). A mixed methods evaluation of the Brain Injury Family Intervention. NeuroRehabilitation, 27, 19–29.

Kristensen, P., Weisæth, L., and Heir, T. (2012). Bereavement and mental health after sudden and violent losses: A review. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 75(1), 76–97.

Laor, N., Wolmer, L., and Cohen, D. J. (2001). Mothers’ functioning and children’s symptoms 5 years after a SCUD missile attack. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 1020–1026.

LeClere, F. B., and Kowalewski, B. M. (1994). Disability in the family: The effects on children’s well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family Counseling, 56, 457–468.

Leroux, T. C., Kum, H. C., Dabney, A., and Wells, R. (2016). Military deployments and mental health utilization among spouses of active duty service members. Military Medicine, 181(10), 1269–1274.

Lester, P., Stein, J.A., Saltzman, W., Woodward, K., MacDermid, S.W., Milburn, N., Mogil, C. and Beardslee, W. (2013). Psychological health of military children: Longitudinal evaluation of a family-centered prevention program to enhance family resilience. Military Medicine, 178, 838–845.

Manguno-Mire, G., Sautter, F., Lyons, J., Myers, L., Perry, D., Sherman, M., Glynn, S. and Sullivan, G. (2007). Psychological distress and burden among female partners of combat veterans with PTSD. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195, 144–151.

Mansfield, A. J., Kaufman, J. S., Marshall, S. W., Gaynes, B. N., Morrissey, J. P., and Engel, C. C. (2010). Deployment and the use of mental health services among U.S. Army wives. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(2), 101–109.

McCarroll, J. E., Fan, Z., Newby, J. H., and Ursano, R. J. (2008). Trends in U.S. Army child maltreatment reports: 1990–2004. Child Abuse Review—Journal of the British Association for the Study and Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect, 17(2), 108–118.

McCarroll, J. E., Thayer, L. E., Liu, X., Newby, J. H., Norwood, A. E., Fullerton, C. S., and Ursano, R. J. (2000). Spouse abuse recidivism in the U.S. Army by gender and military status. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 521.

McCarroll, J. E., Ursano, R. J., and Fullerton, C. S. (1993). Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder following recovery of war dead. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 1875–1877.

________. (1995). Symptoms of PTSD following recovery of war dead: 13-15-month follow-up. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 939–941.

McCarroll, J. E., Ursano, R. J., Newby, J. H., Liu, X., Fullerton, C. S., Norwood, A. E., and Osuch, E. A. (2003). Domestic violence and deployment in U.S. Army soldiers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191(1), 3–9.

Monson, C. M., Taft, C. T., and Fredman, S. J. (2009). Military-related PTSD and intimate relationships: From description to theory-driven research and intervention development. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 707–714.

Nelson, L. J., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Christensen, K. J., Evans, C. A., and Carroll, J. S. (2011). Parenting in emerging adulthood: an examination of parenting clusters and correlates. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 730–743.

Newby, J. H., Ursano, R. J., McCarroll, J. E., Liu, X., Fullerton, C. S., and Norwood, A. E. (2005). Postdeployment domestic violence by US Army soldiers. Military Medicine, 170(8), 643–647.

Noffsinger, M. A., Pfefferbaum, B., Pfefferbaum, R. L., Sherrib, K., and Norris, F. H. (2012). The burden of disaster: Part I. Challenges and opportunities within a child’s social ecology. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 14, 3–13.

Olds, D. L., Eckenrode, J., Henderson, C. R., Kitzman, H., Powers, J., Cole, R., Sidora, K., Morris, P., Pettitt, L. M. and Luckey, D. (1997). Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect. Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278, 637–643.

Owens, B. D., Kragh, J. F., Jr, Wenke, J. C., Macaitis, J., Wade, C. E., and Holcomb, J. B. (2008). Combat wounds in operation Iraqi Freedom and operation Enduring Freedom. Journal of Trauma, 64, 295–299.

Patterson, G. R. (1982). Coercive Family Process. Eugene, OR: Castalia.

________. (2005). The next generation of PMTO models. Behavior Therapist / AABT, 28, 25–32.

Patterson, G. R., Forgatch, M. S., Yoerger, K. L., and Stoolmiller, M. (1998). Variables that initiate and maintain an early-onset trajectory for juvenile offending. Development and Psychopathology, 10, 531–547.

Pessar, L. F., Coad, M. L., Linn, R. T., and Willer, B. S. (1993). The effects of parental traumatic brain injury on the behaviour of parents and children. Brain Injury, 7, 231–240.

Petrik, N. D., Rosenberg, A. M., and Watson, C. G. (1983). Combat experience and youth: Influences on reported violence against women. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 14, 895–899.

Pfeffer, C. R., Karus, D., Siegel, K., and Jiang, H. (2000). Child survivors of parental death from cancer or suicide: Depressive and behavioral outcomes. Psycho-Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer, 9(1), 1–10.

Prinz, R. J. (2016). Parenting and family support within a broad child abuse prevention strategy: Child maltreatment prevention can benefit from public health strategies. Child Abuse and Neglect, 51, 400–406.

Ramchand, R., Tanielian, T., Fisher, M. P., Vaughan, C. A., Trail, T. E., Epley, C., Voorhies, P., Robbins, M., Robinson, E., and Ghosh-Dastidar, B. (2014). Hidden Heroes: America’s Military Caregivers. Santa, Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Rehman, U. S., Gollan, J., and Mortimer, A. R. (2008). The marital context of depression: Research, limitations, and new directions. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(2), 179–198.

Reinherz, H. Z., Giaconia, R. M., Hauf, A. M., Wasserman, M. S., and Paradis, A. D. (2000). General and specific childhood risk factors for depression and drug disorders by early adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 223–231.

Rentz, E. D., Marshall, S. W., Loomis, D., Casteel, C., Martin, S. L., and Gibbs, D. A. (2007). Effect of deployment on the occurrence of child maltreatment in military and nonmilitary families. American Journal of Epidemiology, 165(10), 1199–1206.

Rosenheck, R., and Nathan, P. (1985). Secondary traumatization in children of Vietnam veterans. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 36, 538–539.

Rudenstine, S., Cohen, G., Prescott, M., Sampson, L., Liberzon, I., Tamburrino, M., Calabrese, J., and Galea, S. (2015). Adverse childhood events and the risk for new-onset depression and post-traumatic stress disorder among U.S. National Guard soldiers. Military Medicine, 180(9), 972–978.

Saldinger, A., Porterfield, K., and Cain, A. C. (2004). Meeting the needs of parentally bereaved children: A framework for child–centered parenting. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 67, 331–352.

Saltzman, W. R., Lester, P., Beardslee, W. R., Layne, C. M., Woodward, K., and Nash, W. P. (2011). Mechanisms of risk and resilience in military families: Theoretical and empirical basis of a family-focused resilience enhancement program. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 213–230.

Sameroff, A. (2010). A unified theory of development: A dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child Development, 81, 6–22.

Samper, R. E., Taft, C. T., King, D. W., and King, L. A. (2004). Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and parenting satisfaction among a national sample of male Vietnam veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17, 311–315.

Sandler, I. N., Ayers, T. S., Wolchik, S. A., Tein, J. Y., Kwok, O. M., Haine, R. A., Twohey-Jacobs, J., Suter, J., Lin, K., Padgett-Jones, S. and Weyer, J. L. (2003). The family bereavement program: Efficacy evaluation of a theory-based prevention program for parentally bereaved children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 587–600.

Sayers, S. L., Farrow, V. A., Ross, J., and Oslin, D. W. (2009). Family problems among recently returned military veterans referred for a mental health evaluation. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70, 163–170.