1

Introduction

In response to changes in the composition of the all-volunteer force, the U.S. labor market, and the demands and consequences of military operations, U.S. military programs and policies designed to support service members and their families have changed significantly in recent years. In 2012, the U.S. Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) Family Readiness Policy1 was overhauled, and since then policy makers have made major revisions to the military retirement, compensation, and benefits system, including the new Blended Retirement System and “Forever GI Bill.” The past decade has also seen major fluctuations in military budgets, a decline in the size of the force, and a significant reduction in the extent of operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, even though we remain, after 17 years of engagement in those countries, a nation at war.

Furthermore, dramatic personnel policy shifts now allow gay and lesbian service members to serve openly and women to serve in combat occupations and positions. Significant reorganization efforts include the consolidation of services under the Defense Health System. Most recently, the National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2019 calls for enhancing the readiness of the all-volunteer force, with an emphasis on the importance of supporting service members and their families.

Given the extent of these changes and priorities for ensuring the readiness of the force, this is an opportune time to review key issues central to the well-being of service members and their families so that programs and policies can be strengthened for future mission-readiness.

___________________

1 See https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/134222p.pdf.

Military life brings a diverse set of opportunities, including opportunities for career training and growth, opportunities to see new places and have new experiences, a sense of community, pride, and prestige in serving the nation, and access to many benefits, including health care, high-quality child care, and housing. The capacity of military families to be resilient—to adapt effectively to the unique challenges that military life can present—has been recognized and studied. Unlike many other positive social-emotional attributes, resilience is defined by the adversity in which it develops (Masten, 2001), so the experience of military families has special importance. For instance, young people may take on new roles and responsibilities while their parent is deployed, which may be a source of strength and an opportunity, rather than a challenge (Easterbrooks et al., 2013). In addition, DoD has established policies, programs, services, resources, and practices designed to strengthen families; for example, it has been an innovator in high-quality child care systems. These types of family support systems may increase the likelihood of fostering resilience and preparing parents and children for disruptions in family life due to the military context. Box 1-1 provides key terms related to resilience, readiness, and family well-being used throughout this report. (See Chapter 2 for more detailed descriptions of these terms.)

At the same time, military-connected families and children have a diverse and consistent set of challenges associated with their military affiliation. Most military personnel spend only a limited number of years in the service, but its effects on them and their families, both positive and negative, may persist for many years. Especially for those serving on active duty, frequent moves are an expected aspect of a military career. As a result of the military mission and training requirements, children may be separated from their military parent with some frequency, separations that may last for brief periods or for extended amounts of time. Children of all ages may experience developmental challenges. Further, school-age military-connected children have the additional experience of family relocations that involve school transitions. For military spouses, frequent moves make finding employment and sustaining their careers difficult, and some military families struggle financially. Families of members of the Reserves and National Guard experience the additional dilemma of having to deal with separations due to mobilizations and deployments away from the resources and comradery offered by military installations and their surrounding communities. In addition, there is a military-civilian gap associated, in part, with the fact that in the all-volunteer era only 1 percent of the population serves, which has resulted in a steep decline in the proportion of members of Congress with prior military experience and fewer family connections to the military.2 Research by the nonpartisan Pew

___________________

2 See https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/11/10/the-changing-face-of-americas-veteran-population and https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2011/11/23/the-military-civilian-gap-fewerfamily-connections.

Research Center indicates that individuals with military family connections have different attitudes toward the military than those who do not have family connections. This gap may create more stress for those who are in military families. All of these stressors can bring problems to military families, including anxiety, depression, abuse and neglect, behavioral and academic problems for children, and problems with substance use for young people and their parents.

CONTEXT FOR THE STUDY

This report was prepared at the request of the Military Community Family Policy (MC&FP) office, an organization within the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (OUSD) for Personnel and Readiness. As of late 2018, its mission statement states that MC&FP

. . . is directly responsible for programs and policies establishing and supporting community quality of life programs for active-duty, National Guard and reserve service members, their families and survivors worldwide. The office also serves as the resource for coordination of quality of life issues within the Department of Defense.3

MC&FP responsibilities span the life course of the service member’s military career, from entry into the military through the transition to civilian life, and all of the stages in between including family life. Examples of support programs overseen by MC&FP include the Casualty Assistance Program; Children and Youth programs; the Family Advocacy Program; Family Assistance Centers; Military and Family Support Centers; Military OneSource; Morale, Welfare, and Recreation programs; nonmedical counseling programs; the Spouse Education and Career Opportunities Program; and programs to provide support for deployments and relocations. As such, the OUSD MC&FP asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to provide insights to help the office prioritize its efforts and ensure that program and policy design aligns with its goals of supporting the well-being and readiness of service members and their families.

STUDY CHARGE

Recognizing the importance of supporting service members and their families to promote readiness and resilience, the OUSD MC&FP asked the National Academies to undertake a study to examine the challenges and opportunities facing military families and ways to protect them. The full statement of task for the committee is presented in Box 1-2. This study builds on previous National Academies reports that offered conclusions and recommendations regarding such issues as healthy community development, social support, mental health supports, the effects of multiple deployments on military families, cohesive responses to deployment-related health effects, and ways to address substance use disorders in the military (IOM, 2013a,b; NASEM, 2016, 2018).

___________________

3 For more information see https://prhome.defense.gov/M-RA/Inside-M-RA/MCFP/HowWe-Support.

STUDY APPROACH

The committee’s work was accomplished over a 24-month period that began in October 2017. The committee members represented expertise in psychology, psychiatry, sociology, human development, family science, education, prevention and implementation science, traumatology, public policy, medicine, public health, social work, delivery of services to military populations, and community health services. Six members of the committee are military veterans and several members were or are currently part of a military family (see Appendix A for biographical sketches of the committee

members and staff).4 The committee met six times to deliberate in person, and it conducted additional deliberations by teleconference, web meetings, and electronic communications.

Information Gathering

The committee used a variety of sources to gather information. Public information-gathering sessions were held in conjunction with the committee’s first and second meetings. The first session was held with the study sponsor. The second session provided the committee the opportunity to hear from representatives of service members, their families, and service member organizations who offered their perspectives on topics germane to this study (see Appendix B for the agenda of the second open session). Material from these open sessions is referenced in this report where relevant.

The committee reviewed literature and other documents from a range of disciplines and sources. An extensive review of the scientific literature pertaining to the questions raised in its statement of task was conducted. The literature searches included peer-reviewed scientific journal articles, books and reports, as well as papers and reports produced by government offices and other organizations. The committee also requested brief memos from experts from academia as well as a variety of different organizations that serve military service members and their families. A listing of the memos that the committee received appears in Appendix C.

The committee benefited from earlier reports by the National Academies based on studies conducted within the Institute of Medicine (now known as the Health and Medicine Division). In addition, the committee commissioned papers on diverse topics, including digital interventions, big data analytics, community engagement programs, implementation science, and success factors for effective systems of support for military families.

Scope

The study’s sponsor, the OUSD MC&FP, asked the committee to focus on the active and reserve components in DoD, which include

- Army, Army National Guard, Army Reserve;

- Navy, Navy Reserve;

___________________

4 The National Academies’ policy states that no individual can serve on a committee used in the development of reports if the individual has a conflict of interest that is relevant to the functions to be performed. While neither active nor reserve component members served on this committee, their input was solicited at all phases of the study and played a great role in the committee’s considerations. In addition, six members of the committee are military veterans.

- Marine Corps, Marine Corps Reserve; and

- Air Force, Air National Guard, and Air Force Reserve.

For the reserve component, the committee focused on the Selected Reserves, which refers to the prioritized reserve personnel who typically drill and train 1 weekend a month and 2 additional weeks each year to prepare to support military operations. Other reserve elements, which are not maintained at this level of readiness but could potentially be tapped for critical needs in a crisis, are the Individual Ready Reserves, Inactive National Guard, Standby Reserves, and Retired Reserves. The Coast Guard was excluded. Although Coast Guard members may at times serve in missions under the authority of the Department of the Navy, the Coast Guard belongs to the Department of Homeland Security rather than DoD.

The sponsor asked the committee to consider the well-being of single and married military personnel and their military dependents and also to consider more broadly the network of people who support them. The committee considered the definition of “military family” documented in DoD’s Military Family Readiness Policy which focuses on dependents, yet it also allows for the possible inclusion of individuals who do not meet the legal status of a military dependent:

Military family. A group composed of one Service member and spouse; Service member, spouse and such Service member’s dependents; two married Service members; or two married Service members and such Service members’ dependents. To the extent authorized by law and in accordance with Service implementing guidance, the term may also include other nondependent family members of a Service member (DoDI 1342.22, 2012) (U.S. Department of Defense, 2012, p. 32).

The committee also considered the legal definition of a military dependent as specified in Title 37 U.S.C. Section 401 (see Box 1-3) as it prepared its report.

While the committee referred to the definition used in military policy above, it was directed heavily by research conducted with the general population that suggests greater diversity in family forms than is encoded in the military definition. As a result, the committee was guided by the more inclusive definition of family that appears in Chapter 2.

Note, too, that the study charge asked the committee to consider military families that have recently left the military. Veterans who have completed their military service may be a joint responsibility of DoD and the Department of Veterans Affairs, depending upon their health status and years of service. The Department of Veterans Affairs also provides assistance to some family members, primarily spouses and dependents of disabled or deceased veterans.5

___________________

5 See https://www.va.gov/HEALTHBENEFITS/apply/family_members.asp for more details about health benefits for veterans’ family members.

The committee uses the terms evidence-based and evidence-informed to describe and review programs, practices, and policies (see Chapters 7 and 8). The term evidence-based describes a service, program, strategy, component, practice, and/or process that demonstrates impact on outcomes of interest through application of rigorous scientific research methods, namely experimental and quasi-experimental designs that allow for causal inference (Centre for Effective Services, 2011; Glasgow and Chambers, 2012; Gottfredson et al., 2015; Graczyk et al., 2003; Howse et al., 2013; Kvernbekk, 2016; Schwandt, 2014). Evidence-informed describes a service, program, strategy, component, practice, and/or process that (i) is developed by or drawn from an integration of scientific theory, practitioner experience and expertise, and stakeholder input with the best available external evidence from systematic research and a body of empirical literature; and (ii) demonstrates impact on outcomes of interest through the application of scientific research methods that do not allow for causal inference (Centre for Effective Services, 2011; Glasgow and Chambers, 2012; Howse et al., 2013; Kvernbekk, 2016; Schwandt, 2014). The committee notes later in this report (in Chapters 7 and 8) that some researchers have proposed a paradigm shift in how evidence-based interventions are applied, expanded, and disseminated.

The study charge required the committee to examine the evidence regarding the impact of military life on children and families. The committee notes that the vast majority of extant research on military children and families has provided correlational rather than causal evidence, such as from surveys that gathered data from individuals at a single point in time. These data provide important information about relationships (e.g., among risk factors) but are limited insofar as they are subject to shared method variance (reporter bias) and cannot provide information about directionality (what influences what). The committee relied on the most robust data available (longitudinal, randomized controlled trial, multiple-method, and multiple-informant data). Where no military study data were available, the committee reports on the relevant research from civilian populations.

Where applicable, the committee notes that there are additional contexts, systems, and entities that impact military families. These can include, for example, the formal pre-kindergarten to grade 12 public education system, youth-serving organizations such as the Y and 4-H, and other community-based and faith-based organizations. The committee acknowledges their relevance and importance to military families while noting, at the same time, that these organizations are outside the purview of MC&FP and thus outside the committee’s charge.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES

This report is guided by six guiding principles, as shown in Box 1-4. These guiding principles were identified by the committee and are based on the research evidence on family systems and the unique experiences of military families.

Guiding Principle 1: Lived Experience

First, the committee focuses on the lived experience of military families, meaning that rather than relying upon policy definitions used to determine eligibility for specific military benefits, we consider how families may self-define (Meyer and Carlson, 2014). By recognizing families’ lived experience, the committee aims to show a fundamental respect for families as unique and personal systems and recognize and appreciate the range of families’ capacities to learn and adapt over time. As families learn and negotiate through their individual and collective life course, they evolve in their perspectives as well. Lived experiences can contribute in essential and complex ways to deepened understanding, problem-solving capabilities, discernment about connections, and the maturity in family function. This strategy helps us assess whether DoD’s definitions and priorities leave gaps in the support system for military families.

Guiding Principle 2: Families Are Systems

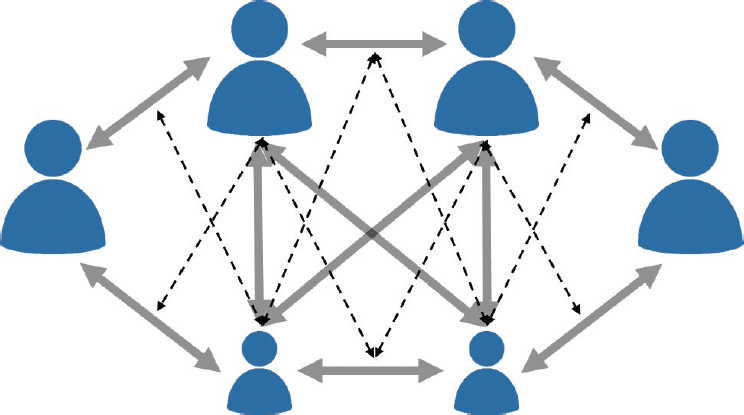

Second, we understand families to be systems, meaning that families comprise not only individuals but also subgroups or subsystems, such as marital or parent-child subsystems (see Figure 1-1). Interactions among family members, both within and across subsystems, form patterns that go beyond

individual characteristics in shaping well-being and responses to adversity for all family members (Cox and Paley, 2003; Repetti et al., 2002). Individuals and subsystems within families are interdependent: The actions of one person can affect not only other individuals in the family but also other subsystems, such as mothers’ actions affecting fathers’ relationships with children. Family systems are dynamic, repeatedly adapting and reorganizing in response to both internal and external conditions (the systems principle of feedback loops; Cox and Paley, 2003). Family systems are diverse in organization, but families commonly work to sustain and re-establish familiar patterns (the systems principle of homeostasis). At the same time, changes in one part of the system can prompt systemwide change, offering multiple entry points for intervention (the systems principle of equifinality). Among the implications for family support systems, such as policies, programs, services, resources, and practices, is that changing the behavior of individuals may need to involve multiple family members, and vice versa, that changing the behavior of an individual may have cascading effects on other family members. Another implication is that there may be multiple pathways to successful outcomes.

Guiding Principle 3: Families Are Embedded in Larger Contexts

Third, as described in more detail in Chapter 2, we understand families to be embedded in larger contexts that both shape and are shaped by families (Bronfenbrenner et al., 1984; Cramm et al., 2018; Lubens and

Bruckner, 2018; Segal et al., 2015). These include physical contexts, such as military installations, neighborhoods, and communities; systems of services or care, such as infrastructures for food or safety and health care or economic systems; and social or cultural settings, such as religious institutions and societal or military values (Bronfenbrenner et al., 1984). Contexts can be thought of as layers surrounding families, some of them quite proximal “microsystem” settings in which family members participate actively, such as workplaces, and other, much more distal “macrosystem” settings in which families do not participate directly but by which they are nonetheless strongly affected, such as government organizations (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2007; Segal et al., 2015).

The levels and types of resources and support available in settings have significant implications for both physical and mental well-being, as acknowledged in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Healthy People 2020 initiative.6 Resources and support can include not only formal policies and programs, but also informal practices that can filter or augment their well-being, such as by limiting or expanding access. Most military families rely on a complex array of formal and informal supports and services provided through their personal networks or by military and civilian organizations. Together, these form a complex interwoven and dynamic system.

For example, most members of active component military families live in civilian communities and many may work or attend school there as well, but they also may have access to military supports and services on or near installations. Reserve component families have regular access to some military supports but intermittent access to others (as we will discuss further in Chapter 4).

Guiding Principle 4: Duration and Timing of Service Must Be Considered

Duration and timing of military service must be considered in relation to military family well-being (Bowen and Martin, 2011; Masten, 2015; Wilmoth and London, 2013). Duration refers to the length of military service or military experiences such as deployments. Timing refers to when events or experiences occur in the lives of individuals, in the family’s history, and in the political or historical context. Exposures to adversity early in life, for example, may have especially serious consequences. Duration is important because short-term events or exposure may have different effects from protracted ones. Chapters 4 and 5 provide more in-depth discussion of duration and timing.

___________________

6 For more information see https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health.

In addition, there have been many calls throughout the period of the all-volunteer force to smooth and ease the transition between military service and civilian status, which is particularly abrupt for family members (DoD Taskforce on Mental Health, 2007; National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2018); hence we pay special attention in this report to issues related to transition. (See Box 1-5 for more details about the all-volunteer force.)

Guiding Principle 5: Military Family Readiness Linked to Mission Readiness

The fifth guiding principle is that military family readiness is directly linked to mission readiness. In 2002, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense released a report describing a “new social compact” (U.S. Department of Defense, 2002, p. 6), which outlined a mutually beneficial partnership between DoD, service members, and their families. According to this report,

the partnership between the American people and the noble warfighters and their families is built on a tacit agreement that families as well as the service member contribute immeasurably to the readiness and strength of the American military. Efforts toward improved quality of life, while made out of genuine respect and concern for service members and families’ needs, also have a pragmatic goal: a United States that is militarily strong.

DoD’s social compact philosophy is undergirded by the notion that “we’re all in this together” in order to have a successful military and defend the security of our nation. As such, the committee used this philosophy as well as the long history of evidence that shows that families are important for military readiness as a backdrop for its conclusions and recommendations in this report. This guiding principle is described in more depth in Chapter 2 and elsewhere throughout the report.

Guiding Principle 6: Implementation Support Is Critical

The final principle that the committee used to guide its report is that implementation support is critical for a sustained and robust Military Family Readiness System (MFRS). The MFRS is defined by DoD as “the network of agencies, programs, services and people, and the collaboration among them, that facilitates and actively promotes the readiness and quality of life of Service members and their families.”7 The MFRS serves both active and reserve component service members and their families, and includes community partners to meet the needs of geographically separated military families, who are not near a military installation.

The policies and programs that comprise the MFRS fall under the purview of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness USD (P&R),8 but they are governed by separate Assistant Secretaries of Defense (ASDs). The vast majority of services and activities are delivered by the individual military services. This division of labor and responsibilities has had some salutary effect on achieving a baseline level of delivery across the system to meet military families’ expectations as they traverse the military lifestyle but has also impeded coordination between and among all of the agencies who are delivering services to the individual service members and their families.

The concept of the MFRS was introduced in the Department of Defense Instruction (DoDI) 1342.22, “Military Family Readiness” in July 2012 under the signature of the then serving Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness. This updated instruction introduced the concept of the MFRS that outlines diverse options for accessing a network of integrated services to help families easily find the support they need for everyday life in the military. According to a 2011 Request for Applications DoD’s goal is to “implement a Military Family Readiness System (MFRS) that is a high quality, effective and efficient DoD-standard, joint-Service training resource (with supporting materials) that prepares Family Center/Family Readiness program staff (management and front line employees)

___________________

7 See https://public.militaryonesource.mil/footer?content_id=282320.

to implement individual programs within the context of a ‘social service delivery system’ model.”9

As further delineated in Chapters 7 and 8, implementation processes are critical to ensuring that programs, services, and resources are delivered with quality and with an appropriate balance of fidelity and adaptation and are efficient in terms of return on investment. Specifically, there is a translation gap between evidence and practice that is likely intensified within the dynamic military context (see Chapter 8 for a detailed discussion). The committee does not have sufficient information to estimate the costs of the MFRS however the recommended MFRS as a learning system (as described in Chapter 7) will lead to cost savings by avoiding spending money on ineffective programs, better targeting of services, and better learning about what is working and what is not.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

This report is organized into nine chapters. Chapter 2 describes what is meant by “family” in the military context and introduces the concept of family well-being. Chapter 2 also attends to the broader literatures on human development, stress exposure, and resilience. Chapter 3 describes the demographic and military service characteristics of military families, including the sources and current state of these data. In Chapter 4, the committee highlights opportunities, stressors, and challenges that military life poses. Chapter 5 focuses on resilience and the impact of stress and trauma on the development of the children of service members. This includes an examination of children’s social-emotional, physical, neurobiological, and psychological development. Chapter 6 examines what is known about the impact of highly stressful or traumatic challenges on the family system. In Chapter 7, the committee presents a framework as a method to build a more coherent, comprehensive approach to military family well-being and readiness and to transform the current MFRS into a coherent, comprehensive, complex adaptive system. Chapter 8 presents the research and components needed to develop a learning community system to support military family well-being. Chapter 9 presents the committee’s recommendations to DoD. Appendix A includes biographical sketches of the committee and project staff. Appendix B includes the agenda for the public information-gathering session. Appendix C lists the individuals and organizations that submitted memos to the committee. Appendix D provides a glossary of terms and an acronyms list.

___________________

9 See https://nifa.usda.gov/sites/default/files/rfa/11_military_readiness.pdf.

REFERENCES

Bowen, G. L., and Martin, J. A. (2011). The resiliency model of role performance for service members, veterans, and their families: A focus on social connections and individual assets. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 21(2), 162–178.

Bronfenbrenner, U., Moen, P., and Garbarino, J. (1984). Child, family, community. In R. D. Parke (Ed.), Review of Child Development Research (vol. 7, pp. 283–328). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., and Morris, P. A. (2007). The bioecological model of human development. In W. Damon and R. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology (6th ed., vol. 1, pp. 793–828). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Carter, P., Kidder, K., Schafer, A., and Swick, A. (2017). Working Paper, AVF 4.0: The Future of the All-Volunteer Force. Washington, DC: Center for New American Security.

Centre for Effective Services. (2011). The What Works Process: Evidence-Informed Improvement for Child and Family Services. Dublin, Ireland: Centre for Effective Services.

Cox, M. J. and Paley, B. (2003). Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 193–196.

Cramm, H., Norris, D., Venedam, S., and Tam-Seto, L. (2018). Toward a model of military family resiliency: A narrative review. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10(3), 620–640.

DoD Task Force on Mental Health. (2007). The Department of Defense Plan to Achieve the Vision of the DoD Task Force on Mental Health: Report to Congress. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Defense. Available: file:///N:/BOCYF%20Projects%20-%20Current/Military%20Families/Relevant%20Literature/91907DoDTaskForceMentalHealth.pdf.

Easterbrooks, M. A., Ginsburg, K., and Lerner, R. M. (2013). Resilience among military youth. The Future of Children, 23(2), 99–120.

Glasgow, R. E., and Chambers, D. (2012). Developing robust, sustainable, implementation systems using rigorous, rapid and relevant science. Clinical and Translational Science, 5(1), 48–55.

Gottfredson, D. C., Cook, T. D., Gardner, F. E., Gorman-Smith, D., Howe, G. W., Sandler, I. N., and Zafft, K. M. (2015). Standards of evidence for efficacy, effectiveness, and scale-up research in prevention science: Next generation. Prevention Science, 16(7), 893–926.

Graczyk, P. A., Domitrovich, C. E., and Zins, J. E. (2003). Facilitating the implementation of evidence-based prevention and mental health promotion efforts in schools. In Handbook of School Mental Health Advancing Practice and Research (pp. 301–318). Boston: Springer.

Howse, R. B., Trivette, C. M., Shindelar, L., Dunst, C. J., and The North Carolina Partnership for Children, Inc. (2013). The Smart Start Resource Guide of Evidence-Based and Evidence-Informed Programs and Practices: A Summary of Research Evidence. Raleigh, NC: The North Carolina Partnership for Children, Inc.

Institute of Medicine. (IOM) (2013a). Returning Home from Iraq and Afghanistan: Assessment of Readjustment Needs of Veterans, Service Members, and Their Families. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

_________. (2013b). Substance Use Disorders in the U.S. Armed Forces. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kelty, R., and Segal, D. R. (2013). The military as a transforming influence: Integration into or isolation from normal adult roles? In J. M. Wilmoth and A. S. London (Eds.), Life Course Perspectives on Military Service (pp. 19–47). New York, NY: Routledge.

Kvernbekk, T. (2016). Evidence-based Practice in Education: Functions of Evidence and Causal Presuppositions. New York, NY: Routledge.

Lubens, P., and Bruckner, T. A. (2018). A review of military health research using a social-ecological framework. American Journal of Health Promotion, 32(4), 1078–1090.

Masten, A. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238.

_________. (2015). Pathways to integrated resilience science. Psychological Inquiry, 26(2), 187–196.

Meyer, D. R., and Carlson, M. J. (2014). Family complexity: Implications for policy research. ANNALS of the American Academy of Political Social Sciences, 654(1), 259–276.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). (2016). Gulf War Health: Volume 10: Update of Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War, 2016. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

_________. (2018). Evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2018). After Service: Veteran Families in Transition. Retrieved from https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/resources//after_service_veteran_families_in_transition.pdf.

Repetti, R. L., Taylor, S. E., and Seeman, T. E. (2002). Risky families: Family social environments and the mental physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin, 12(8), 330–366.

Schwandt, T. A. (2014). Credible evidence of effectiveness: Necessary but not sufficient. In S. I. Dondalson, C. A. Christie, and M. M. Mark (Eds.), Credible and Actionable Evidence: The Foundation for Rigorous and Influential Evaluations (2nd ed., pp. 259–273). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Segal, M. W., Lane, M. D., and Fisher, A. G. (2015). Conceptual model of military career, family life course events, intersections, and effects on well-being. Military Behavioral Health, 3(2), 95–107.

U.S. Department of Defense. (2002). A New Social Compact: A Reciprocal Partnership Between the Department of Defense, Service Members, and Families. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/A%20New%20Social%20Compact.pdf.

_________. (2012). Department of Defense Instruction: Military Family Readiness. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/134222p.pdf.

Wilmoth, J. M., and London, A. S. (2013). Life Course Perspectives on Military Service. New York, NY: Routledge.

This page intentionally left blank.