2

Family Well-Being, Readiness, and Resilience

In this chapter, the committee lays the foundation for subsequent chapters by establishing the importance to the U.S. Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) mission of the well-being, readiness, and resilience of military families, including the service members in them. After reviewing the evidence concerning family well-being, the committee lays out its approach to this subject from objective, subjective, and functional perspectives. This is followed by a discussion of the ways various dimensions of family well-being within the military context are illuminated by developmental science, bioecological models of individual and family development, and life course theory. Equal importance is placed on reviewing the concepts of family readiness and resilience within the military context. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the measurement of family resilience, which finds that while there are no comprehensive measures, there are still well-established measures that can be used to assess many of the major components of resilience and readiness.

The well-being of military families is essential to DoD for multiple reasons. First, family well-being is an important consideration to individuals who are deciding whether to enter or remain in military service (Keller et al., 2018; Meyers, 2018). The resources that DoD provides to support family well-being can help to make military service more attractive than civilian employment. Second, family difficulties can be costly to DoD due to the expenses incurred in response to legal, medical, mental health, or financial problems (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2013; Lubens and Bruckner, 2018). Service members’ psychological or physical difficulties

can reverberate within families, potentially generating costs for DoD (IOM, 2013). Years ago, the Army Science Board (an independent advisory group to the Secretary of the Army) concluded: “Recognition of the powerful impacts of the family on readiness, retention, morale and motivation must be instilled in every soldier from the soldier’s date of entry-to-service through each succeeding promotion” (Schneider and Martin, 1994, p. 25).

Third, family difficulties can detract from a service member’s readiness for and focus on the military mission. Family members provide support to service members while they serve and when they have difficulties; family problems can interfere with the ability of service members to deploy or remain in theater; and family members are central influences on whether members continue to serve (Keller et al., 2018; Meyers, 2018; Schneider and Martin, 1994; Shiffer et al., 2017; Sims et al., 2017).

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, service members’ families support the military mission by supporting them while they serve, making it possible for service members to leave home to train and deploy, and providing significant care for service members when they are wounded, ill, or injured (IOM, 2013). Service members must rely even more on their families during and following the transition from military service to civilian life, when access to DoD resources shrinks. Given that most family members cannot receive services from the Veterans Administration (VA), this time of transition may be especially challenging.

LINKAGES BETWEEN FAMILY ISSUES AND MILITARY READINESS

Most of the evidence regarding links between family issues and military readiness assumes or ignores the positive contributions of families to military service. An exception is the literature related to choosing military service, which shows that parents appear to be important influencers of youths’ decisions to enlist and to take tangible steps toward doing so (Gibson et al., 2007; Legree et al., 2000). In addition, family structure while growing up is related to propensity to serve. For example, the large, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health or Add Health study found that youth raised in families by stepparents or social (i.e., non-biological) parents were approximately twice as likely to enlist rather than go to college as youth from families with two biological parents, even after controlling for socioeconomic status (Spence et al., 2013).

Family-related factors are associated with job performance during military service. In the 2011 Health-Related Behaviors Survey (Barlas et al., 2013), service members reported that conflicts between military and family/personal responsibilities and separation from family or friends were among the top three stressors of military life (see Table 5-2). In a large study at Fort Jackson, male service members with a marital status of separated, divorced,

or widowed were at an increased risk of medical discharge from basic training (Swedler et al., 2011). In data from the 2002 DoD Health-Related Behaviors Survey of Active Duty Personnel, occupational stress, which was significantly related to both mental health problems and work performance, was highest among married service members living away from their spouses (Hourani et al., 2006).

Family factors also have implications for the performance of military members during deployments. In one small but dyadic study, Carter and colleagues (2015) found that communication between partners was robustly related to deployed male soldiers’ reports of being able to focus on their jobs. Data from the 2010 Joint Mental Health Advisory Team 7 (2011), gathered in the Middle East from deployed soldiers and Marines, indicated that between 11 and 16.7 percent of married service members, and between 6.4 and 8.5 percent of single service members, perceived that stress or tension related to their families was producing preoccupation or lack of concentration or making it hard to do their military jobs. Family issues were comparable to combat experiences in their relationship to sleep quality and visits to behavioral health care providers.

Specifically regarding military readiness, Schumm and colleagues (2001) tabulated results from multiple samples of Army soldiers showing that family-related factors were significantly related to multiple indicators of soldier readiness. Data from more than 4,500 Army participants in the 1992 DoD Survey of Officers and Enlisted Personnel indicated that soldiers’ perceptions of spouses’ satisfaction with soldier family time and soldiers’ satisfaction with the environment for families both were significantly related to satisfaction with military life and their military job, after controlling for years of service, unit morale, and unit readiness. In the 1991–1992 Survey of Total Army Personnel, soldiers’ self-ratings of readiness and satisfaction with military life were significantly related to how often Army responsibilities created problems for their families, as well as stress in their personal or family lives (Schumm et al., 2001).

There is a long history of evidence that families are important for military retention. Rosen and Durand (1995) summarized some of this literature, citing studies from multiple branches showing that service members were more committed to military service if they were married and that spouses’ attitudes were implicated in service members’ retention decisions. Analyzing longitudinal data they collected from more than 1,200 Army spouses (776 spouses participated in the follow-up survey 1 year after deployment) of enlisted service members deployed for Operation Desert Storm, they found that after controlling for rank, years of service, and spouses’ expectations, the key predictors of attrition for junior spouses were marital problems and the number of years as a military spouse. The single largest predictor of intentions to leave service was the degree to which

spouses perceived it as compatible with family life. Among midlevel noncommissioned officer (NCO) spouses, the strongest predictors of attrition were marital problems and spouses’ wishes; these also were significant predictors of intentions to leave service (Rosen and Durand, 1995). During the Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom (OIF/OEF) conflict, married enlisted members in the Neurocognition Deployment Health Study (n = 740) were almost twice as likely as others to remain in military service 12 months following return from deployment (Vasterling et al., 2015), with the role of marital status being similar in magnitude to those of unit support, pay grade, and age. By comparison, military occupational type, stressful war zone events, and mental health problems were not significantly related to retention.

Lancaster and colleagues studied retention among more than 400 National Guard service members of a brigade combat team deployed in 2006 (Lancaster et al., 2013). Surveys were administered immediately prior to and 2 to 3 months following deployment. Social support during deployment from military leaders and unit members was significantly and positively related to intentions to reenlist for both men and women, while predeployment concerns about family disruption were not. Postdeployment stressors, which included job loss, divorces, financial stressors, and other family-related experiences, were significantly and negatively related to intentions to reenlist. Among 282 participants in a later data collection, actual enlistment behavior was closely related to their earlier intentions.

There is some evidence that family-related issues may be even more important to the retention of female than male service members. In a recent small qualitative study of women veterans, most reported leaving military service before they planned or wished to, primarily because of personal health problems or responsibilities for children (Dichter and True, 2015). These findings echo the results of earlier longitudinal research by Pierce (1998), which showed that Air Force women who became mothers in the 2 years following the launch of Operation Desert Storm were twice as likely to leave military service as women who did not have children. Across the full sample, there were five reasons for leaving that were each reported by more than 20 percent of the respondents. Separation from family and friends and work-family conflict were comparable in prevalence to dissatisfaction with work conditions and somewhat less common than concerns about lack of promotion/recognition and deployment.

More recently, Kelley et al., (2001) studied 154 mothers serving in the Navy, who were divided into a nondeploying group and a group that deployed just prior to 2001. About 80 percent of their children were ages 3 or younger. Two interviews were conducted prior to and following deployment. For both groups, reenlistment intentions at the second interview were significantly related to military benefits and to work-family concerns,

which were identified by one-third of the mothers as reasons for planning to leave service. Experiencing deployment was associated with a greater sense of integration into the Navy, which in turn was positively related to intentions to reenlist.

Family issues are also implicated in the mental health of service members. In a study of previously deployed Canadian military personnel (n = 14,624), the relationship between combat exposure and mental health problems was stronger among married than unmarried personnel, possibly due to the interpersonal challenges of marriage (Watkins et al., 2017). Another study, which examined the records associated with over 700 cases of death by suicide among Army National Guard members between 2007 and 2014 (Griffith and Bryan, 2017), found that parent-family relationship issues were among the top five most common factors, implicated in 27.5 percent of the cases, along with military performance problems (36.4%), substance use (27.3%), and income difficulties (22%). Divorce or separation were present in 15 percent of the cases. Among soldiers who died by suicide within 365 days of return from deployment, parent-family problems were the most common factor—tied with transition problems and substance use during the first 120 days, and more than 8 percentage points more common than the next most common factors during the remainder of the first year.

Family issues are often thought of as potential problems for military service, despite evidence that families appear to be positive influences on joining or remaining in the military, on perceiving oneself as well-prepared for military duties or performing them well, and on the receipt of support and assistance while serving. The importance of families for DoD was reaffirmed by Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Admiral Michael Mullen when the Total Force Fitness directive was crafted in 2010. A resilience-based framework, Total Force Fitness recognizes families as “central to the total force fitness equation” (Land, 2010, p. 3). An article summarizing the evidence base for Total Force Fitness asserts that “social and family fitness are essential to total force fitness and impact performance from such disparate areas as the rate of wound healing to overall unit functioning” (Jonas et al., 2010, p. 12).

DEFINING FAMILY

There is no universal definition of family, and little evidence of a “best” family form, as family structures have changed continuously throughout history. In the United States, for example, the nuclear family form became prominent following World War II; households prior to that time were much more likely to include nonrelatives (Furstenberg, 2014). At any given time, multiple “official” definitions are operating across and even within

government agencies, DoD included (IOM, 2013). The ability to understand increases in family diversity and complexity is limited by how families are defined for the purposes of tabulation. The U.S. Census Bureau currently uses the following definition:

A family is a group of two people or more (one of whom is the householder) related by birth, marriage, or adoption and residing together; all such people (including related subfamily members) are considered as members of one family. Beginning with the 1980 Current Population Survey, unrelated subfamilies (referred to in the past as secondary families) are no longer included in the count of families, nor are the members of unrelated subfamilies included in the count of family members.1

Groups of individuals who do not conform to this definition are not counted by the Census Bureau as families, obscuring knowledge about actual families—those who do not live together and couples who are unmarried, to take two examples. The rise of family diversity and complexity has increased the difficulty of assigning individual families to a single category in a standardized list (Cherlin and Seltzer, 2014). Meyer and Carlson (2014) suggest that it may be necessary in the future to categorize families along several dimensions, including such variables as the presence of children, social versus biological parents or siblings, and nonresidential children or parents. In Canada, the Vanier Institute of the Family has begun to intentionally refer to families according to their functional roles rather than their structure, referring for example to “solo,” “lead,” or “co-” parents rather than to single or married parents, accommodating the reality that partners, grandparents, or even nonrelatives may play these roles (Spinks, 2018).

For the purposes of this report, the committee considers the following as family:

- People to whom service members are related by blood, marriage, or adoption, which could include spouses, children, and service members’ parents or siblings.

- People for whom service members have—or have assumed—a responsibility to provide care, which could include unmarried partners and their children, dependent elders, or others.

- People who provide significant care for service members.

DEFINING FAMILY WELL-BEING

There is no universal definition of family well-being in the research literature or across national and global organizations. With regard to well-

___________________

1 See https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/technical-documentation/subject-definitions.html#family.

being among individuals, the World Health Organization (WHO) pivoted away from a purely medical perspective in an earlier conceptualization, arguing that individual “health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 1948, p. 1). The Healthy People 2020 (HP2020) Framework for individual well-being2 asserts that health and well-being are determined not only by individual-level health behaviors but also by broad social-structural influences such as the characteristics and functioning of families and communities. Because individual health and well-being depend on social determinants, the well-being of individuals is tightly connected with that of families.

The committee considered family well-being from three perspectives: objective, subjective, and functional (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2018; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2017; Skomorovsky, 2018). Objective well-being refers to resources considered necessary for adequate quality of life, such as sufficient economic and educational resources, housing, health, safety, environmental quality, and social connections (OECD, 2017). One example of an objective standard is budgets created to identify the minimum income necessary for family self-sufficiency.3 For military families, the ability to meet such budgets depends on several conditions: whether service members and their partners have adequate employment opportunities, pay, and benefits (Mason, 2018; Military Officers Association of America, 2018); whether families are able to afford adequate housing in safe neighborhoods; whether the environments where families live and work are free of significant threats to health and safety and offer opportunities and support infrastructures that are available, accessible, and affordable; and whether families have adequate networks of informal support.

Subjective well-being is the result of how individuals think and feel about their circumstances, and family well-being is higher when multiple family members experience high subjective well-being. Feelings of happiness and pleasure are the focus of the “hedonic” perspective on well-being (OECD, 2017; Ryan and Deci, 2001), while the “eudaimonic” perspective emphasizes self-actualization (Keyes, 2006). The latter perspective focuses on the cultivation of a meaningful life, one in which a person is able to exercise personal choice, gain a sense of competence and mastery, cultivate healthy relationships, and find meaning and purpose in life. Good health, particularly mental health, comprises high hedonic and eudaimonic well-being.

___________________

2 This is an initiative of the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which was launched in 2010 to provide an agenda for the nation’s health. See https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/About-Healthy-People.

3 For more information, see http://www.selfsufficiencystandard.org.

Third and finally, well-being may also be viewed from a functional perspective, which focuses on the degree to which families and their members can and do successfully perform their core functions, such as caring for, supporting, and nurturing family members. Although positive family functioning involves skills and abilities that are common and perhaps often thought to be “natural,” many of them can be taught and strengthened with education. A variety of standardized instruments exist to assess aspects of family functioning, such as the quality of communication between spouses or partners, parenting and co-parenting, and also general family functioning. Although there is no single consensus definition of functional family well-being, a recent Australian report (Pezzullo et al., 2010, p. 6) defines positive family functioning as

characterised by emotional closeness, warmth, support and security; well-communicated and consistently applied age-appropriate expectations; stimulating and educational interactions; the cultivation and modelling of physical health promotion strategies; high quality relationships between all family members; and involvement of family members in community activities.

Though they are not synonymous, these three different types of well-being are interrelated: if one is rated as high, the other two are more likely to be rated high as well, and if one is rated as low, likewise the other two are more likely to be rated low. In general, however, it is important to note that more is known about the indicators and determinants of individual than family well-being.

MILITARY-FOCUSED DEFINITIONS OF WELL-BEING

DoD does not have an agreed-upon definition of family well-being. Although the Defense Center of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury (2011) referred to “core components” of well-being as happiness and life satisfaction, consistent with subjective well-being, objective and functional well-being also have operational relevance for DoD. The significance of subjective well-being stems from the way it is linked with service members’ and family members’ willingness to continue serving. Objective family well-being is essential, given that DoD must successfully compete with private employers for workers and thus needs to provide compensation, benefits, and support for an adequate quality of life. Functional well-being is important as well, because DoD relies on families to support service members’ ability to perform their missions, care for them when wounded, ill, or injured, and support transitions to civilian life.

Data currently gathered or monitored by DoD, for example through the Status of Forces Surveys (see Chapter 3), provide information about

some aspects of family well-being. But this information primarily concerns subjective well-being, while information about objective and functional well-being is limited or lacking.

TRENDS IN FAMILY LIFE

In most Western societies, including the United States, industrialization over the past 150 years has been accompanied by significant changes in the work and family behavior of both men and women, especially mothers (Furstenberg, 2014). In the United States since World War II, family structures have become substantially more diverse as connections among partnering, marriage, and childbearing have weakened (Cherlin and Selzer, 2014). Cohabiting is now as common as marriage, which occurs later in life, if at all. Moreover, 40 percent of children are now born to parents who are not married, although the percentage of parents with partners has not changed (Cherlin, 2010). There also have been substantial declines in the average number of births per woman (Cherlin, 2010; OECD, 2011). Other trends contributing to family diversity include increases in the prevalence of shared custody of children following divorce and in the number of couples who do not live together, same-sex couples, and mixed-immigration-status families.

Young adults today are likely to have accumulated more family transitions, such as marriage, divorce, or changes in household composition, than their predecessors, and their own children are likely to share this characteristic. For example, the proportion of young adults now occupying more than one parental role (e.g., having not only residential biological children but also residential “social” children4 or nonresidential biological children) prior to age 30 has risen by close to 50 percent (Berger and Bzostek, 2014). The percentage of children not living with both biological parents increased in the 1970s and 1980s, but largely stabilized in the 1990s at about 40 percent (Manning et al., 2014). The proportion of children living in three-generation households has risen, increasing the involvement of grandparents in some children’s lives (Dunifon et al., 2014). Children in families today are more likely to have ties to parents or siblings in multiple households than in the past (Cherlin and Seltzer, 2014).

In addition, some individuals, traditionally women, may find themselves “sandwiched” between simultaneous caregiving roles and responsibilities. The Pew Research Center estimates that there are more than

___________________

4Social children are those who are not biological, step, or adopted, such as when an unmarried partner brings his or her biological children to a cohabiting relationship. Those children are social children for the partner—there is no legal status, but the partner may function as a parent.

40 million unpaid caregivers of adults age 65 and older (Pew Research Center, 2015). The committee notes that for military families, there are two possible roles in which caregivers and/or spouses may be sandwiched: (i) an adult child caring for an older parent; or (ii) a younger adult, such as a wounded service member, being cared for by a spouse, adult sibling, or parent. A recent systematic review of the literature on veterans’ informal caregivers found that there was limited relevant research with regard to informal caregiving of individuals with disabilities, and there were few studies conducted on protective factors for caregivers of both older (over age 55) and younger family members (Smith-Osborne and Felderhoff, 2014). However, as discussed in more detail in Chapter 3, less than 1 percent of active component dependents (0.6%) and less than one-half of a percent of reserve component dependents are adult dependents who are not the spouses or children of service members.

Some scholars view these increasingly diverse family forms as a continuation of longstanding trends (Biblarz and Stacey, 2010), but others express concern, particularly about a specific form of family diversity labeled family complexity, which is tied to multipartner fertility (i.e., where one person has children with multiple partners). This latter pattern tends to produce families that are unstable, because the structure of the family or the household (or both) changes frequently, increasing the risk of negative consequences for family members. The prevalence of multipartner fertility among parents with at least two children is estimated to range from 23 percent of fathers ages 40–44 and 28 percent of mothers ages 41–49 (Guzzo, 2014).

Multipartner fertility and the family instability that often accompanies it may have negative implications for children. Evidence from a large national sample indicates that children who live with single or cohabiting parents receive less total caregiving time than children living in married-couple or three-generation households (Kalil et al., 2014). Children living apart from a biological parent receive less caregiving from that parent, benefit less from that parent’s earnings, experience more transitions in living arrangements, and are at increased risk of maltreatment at the hands of social parents (i.e., an unmarried partner of the parent with whom children live; Sawhill, 2014). Thus, rising family instability, or frequent changes in the composition of families or households, in the United States is a potentially problematic development.

In the United States, multipartner fertility is more common among low-resource populations. Recent decades have seen a widening educational divide in family structure, such that college-educated individuals are more likely to get married, stay married, and have children while married than individuals with only a high school education (Furstenberg, 2014; Manning et al., 2014). Furstenberg (2014) links these trends to rising economic inequality and the ongoing transformation of roles within families. He

points out that limited economic resources can make individuals hesitant to make marital commitments and make it difficult to obtain birth control and to develop the skills necessary to sustain family relationships, with negative implications for family well-being and functioning. In addition, a recent report from the World Family Indicators Family Map Project indicates that growth in cohabiting (as opposed to single-parent families) predicts growth in family instability (Social Trends Institute, 2017). In summary, both family diversity and family complexity are rising, but it is family complexity that is associated with family instability.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

There may be a large and rising number of families that are invisible because they are neither tabulated nor targeted in family readiness efforts (Hawkins et al., 2018; Meyers, 2018). Examples of invisible families may include same-sex-headed households and families as well as co-parenting but unmarried families. Given that half of the military force is unmarried—a portion of which is certainly in committed relationships—this risk could be substantial. Consequently, to the extent that family forms continue to become more diverse, DoD policies, programs, services, resources, and practices could become increasingly misaligned with actual family structures. Because the prevalence of invisible families is by definition not regularly documented, knowledge is further limited about recent trends related to military family diversity, complexity, and stability.

Across DoD, the term “military family” typically refers to service members and their spouses and/or children, consistent with eligibility rules for military benefits (see Chapter 1). These eligibility conditions are in part bounded by lawmakers who allocate funding to DoD. For example, Congress determines who can be considered “military dependents” for the purposes of benefits through U.S. law.5 Most military dependents are spouses or children of service members, but other individuals, such as parents, also may qualify under certain circumstances, as the definitions provided in Chapter 1 indicate. In practice, however, rules and practices governing eligibility of family members vary across programs and services. For example, while they would not normally be classified as military dependents, service members’ parents, unmarried partners, and others are sometimes invited to participate in deployment briefings, permitted to participate in some activities, or allowed to use facilities on military installations (Thompson, 2018). Other rules are less inclusive, such as those that restrict the eligibility

___________________

5 U.S. Code, Title 37 (“Pay and Allowances of the Uniformed Services”), Chapter 7 (“Allowances”), Section 401 (“Definitions”). See https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2010-title37/html/USCODE-2010-title37-chap7-sec401.htm for more information.

of single parents or applicants with two dependents for military service (see DoD Instruction 1304.26).6

Because military service has lengthened in the all-volunteer era, service members are now older and more likely to have partners and children; the population of spouses and children alone exceeds the population of service members (U.S. Department of Defense [DoD], 2017a). Because family eligibility for programs and supports is necessary for family members to be able to perform important functions that support military missions, this eligibility requirement is especially challenging for service members who are unmarried or childless. Considerable evidence indicates that service members’ well-being is closely connected to the well-being of family members (IOM, 2013). Family members are also important for military retention, especially for women (Keller et al., 2018). DoD acknowledged some of these themes in its articulation of a “social compact” with service members and their families in 2002, which remains relevant today (DoD, 2017b; Office of Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Military Community and Family Policy, 2002).

Historically, DoD has relied on marriage as a gateway to a variety of resources, such as access to military housing or housing allowances, and the ability to take partners on accompanied tours of duty. This marriage-focused stance has been credited with positive consequences, such as reducing racial disparities in marriage and divorce relative to the general population and producing higher rates of marriage as opposed to cohabiting (IOM, 2013), which in turn may help to minimize the flux experienced by children, particularly children of male service members (Hawkins et al., 2018). Some evidence also suggests, however, that military members have high rates of early marriage, increasing the prevalence of divorce and remarriage in this population (Adler-Baeder et al., 2006).

The accumulation of family transitions, which is generally not captured by snapshot assessments at any single point in time, may have implications for later individual well-being and family functioning. Individuals who currently have the same marital status, for example, may have quite different family responsibilities because of differences in their respective histories of family transitions and family instability. The focus on marriage and legal dependents in military policy also means that far more is known about certain kinds of military families—service members (mostly male) with civilian spouses, and their custodial children—than others, such as unmarried partners, or service members’ parents and siblings, who are functionally invisible to DoD.

___________________

6 For example, for those interested in applying for admission to the United States Military Academy West Point, the FAQ page states, “You must not be married, pregnant, or have a legal obligation to support a child or children.” See https://westpoint.edu/admissions/apply-now.

Over time, marital status is becoming less useful as an indicator of family structure because connections are weakening between when or with whom individuals form relationships, and whether or when they marry, share households, or have children. It also is important to recognize that almost all service members, including those who are unmarried, are part of some form of family, and many receive assistance from informal support systems while they perform military duties, when they deploy, or when they become injured (Polusny et al., 2014). Although there have so far been few studies documenting the support systems of unpartnered service members, the largest one conducted to date found that more than 60 percent of parents in the sample reported daily or almost daily communication with their service member children, regardless of their partner status. Parents’ concerns about their military child’s deployment proved protective for service members’ post deployment symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression (Polusny et al., 2014). DoD’s stance regarding privileging certain family forms may be related to the degree to which individuals are willing to choose military service over civilian employment, and service members’ informal systems of support are well prepared to facilitate fulfillment of military duties with minimal negative consequences.

Rising family diversity and complexity have several implications for DoD (Gribble et al., 2018). First, individuals entering the military today may have experienced more family transitions as children than their predecessors. Second, today’s service members may create new families that are more diverse or complex than those their predecessors created (Adler-Baeder et al., 2006). Third, fully understanding military families and their needs may require greater attention to family diversity and complexity. Fourth, the rising diversity and complexity may increase the difficulty of creating military policies, programs, services, resources, and practices that adequately support families in the performance of military duties.

ECOLOGICAL AND LIFE COURSE MODELS OF MILITARY FAMILY WELL-BEING

To understand the dimensions of military family well-being, we apply the principles of developmental science (Lerner, 2007), bioecological models of individual and family development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2007), and life course theory (Wilmoth and London, 2013). Central to all three of these multilayered models are two principles: that development over the lifespan is a dynamic, transactional, and relational process that unfolds, affects, and is influenced by social contexts; and that individuals are “active ingredients” in their own development, from infancy through old age (Lerner, 2007; Sameroff, 2010).

According to developmental systems theory, there is tremendous diversity both within individuals, who have the potential for multiple developmental outcomes, and among individuals and groups. As the actors, people shape their experiences and well-being by responding to and evoking a variety of responses from the environment and within social and family relationships (Darling, 2007). As proposed by Masten (2013), the well-being of military-connected family members and their children may be understood within developmental systems theory as “the idea that a person’s adaptation and development over the life course is shaped by interactions among many systems, from the level of genes or neurons to the level of family, peers, school, community, and the larger society” (Masten, 2013, p. 199).

The concept of purposive development further explains that as individuals move through the life course, they have the capacity to be intentional in shaping their lives, through decision-making and choices (Aldwin, 2014). Individual growth and development for service members, partners and spouses, and children unfold in relationship to the opportunities, context, and confines of military life and structure, throughout the family’s service and beyond. Segal and colleagues’ (2015) military life course model highlights service members’ stress points, such as deployment or injury, as well as family life events, whether specific to military life or not (e.g., birth of child), that affect all members of the family system simultaneously (Segal and Lane, 2016; Segal et al., 2015).

Centering the Family

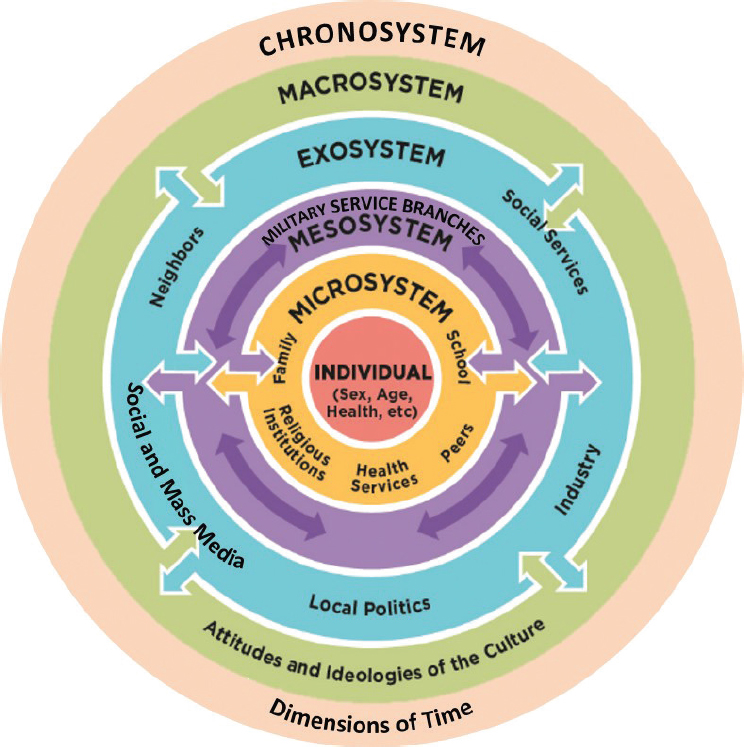

Bronfenbrenner and Morris’s (2007) bioecological model of multilayered systems includes the microsystem at the center and expands through the mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem (see Figure 2-1).

What is critical in applying this model to military family well-being is the question of who is centered within the microsystem. From DoD’s perspective, the service member has historically been the key focus, while Military Community and Family Policy (MC&FP) centers the military family system, the military child, partners, spouses and caregivers, as well as the individual service member, depending upon the program or service. Military culture, command structure, mission, rank, component, and DoD policies operate throughout the service member and military family systems. Arguably, the characteristics of the micro- and mesosystems for service members and family members are distinct although they share characteristics and interact. For example, the level of acculturation to the military context may be uneven across service members and their family members, and it will be influenced by the family’s location, such as whether it is near or on an installation or in a civilian community, and by the density of the

SOURCE: Adapted from Small et al. (2013).

local military population. Acculturation will also be influenced by component, by the individual family member’s history of service, that is, whether he or she is new to the military or earlier generations have served, and by demographic characteristics, such as first language and racial, ethnic, and cultural background. Theories of acculturation are also helpful in understanding specific transitional experiences of military service members returning to the United States after deployment and in understanding the transition/reintegration challenges that may accompany the shift to civilian or other post-service life (Demers, 2011).

In this framework, a service member’s microsystem is the most immediate environment in which he or she lives. It includes individual or intra-

personal characteristics, such as temperament, emotion regulation, and behavior, relational processes with family and friends, and interactions with the immediate military context. The last includes his or her military role and mission, relationships with unit and leadership, and ability to function within a strict command structure. Service member agency is especially visible during important transition points across a military career, such as the decision to join, choice of friends and significant others (e.g., “linked lives”) during service, and the timing of life course transitions such as intimate partner commitment and parenthood. The concept of “linked lives,” which is borrowed from the family life-course literatures and consistent with bioecological theory, describes the interconnectedness and intergenerational nature of family relationships, such as couple and parent-child relationships. Elder and colleagues (2003) discuss the term and theoretical framework to explain that each member of a family will influence and also will be affected by the other members of the family system. In the context of military families, this concept is useful in considering how the life course trajectories of service members’ partners and children, in particular, are directly linked to the service member’s career moves, deployments, and required trainings.

Elder and colleagues’ research, which the examined life-course trajectories of World War II veterans, suggests that the timing of these critical decisions will have a significant impact on the service member’s developmental trajectory and life course (Elder et al., 2009). For instance, the decision to enlist has the potential to function as a “recasting experience” for young male service members who join at an early age. Wilmoth and London (2013) discuss “cumulative exposure” and early life disadvantage and hypothesize “that participation in the military can exacerbate, ameliorate, or have no moderating effect on early life disadvantages” (p. 9). Thus, the formation of the service member’s military identity occurs in tandem with the transition to adulthood.

The next outer ring of the ecological framework includes the mesosystem, which encompasses the linkages between and among the service member and the everyday microsystems in which he or she lives, such as work, interactions with unit and leadership, school, training, and family. For the service member, this setting is centrally defined by the service branch to which the service member has committed. Relatedly, the culture and structure of each service branch are variable and include housing and residence, the persons whom the service member lives with and interacts with socially, work and training environments, and neighborhood communities. Service members must move back and forth between deployment settings, work or training contexts, and their home life—and each of these requires vastly different coping strategies and skills. More distal influences on military families include events that indirectly impact the family’s imme-

diate environment (Bronfenbrenner, 1993) as well as local cultural attitudes about the military, its personnel, and U.S. involvement in foreign wars.

For example, there is variation across regions of the United States in the density of military personnel and the degree of political support for the military. In addition, ever since the end of the draft, there has been a pattern of underrepresentation of service members from the Midwest and the northeastern corridor, relative to the southern states (Maley and Hawkins, 2018). Finally, military families must adapt to local contexts, which vary in terms of acceptance of LGBT persons and support for same-sex marriage, attitudes toward immigrant families, and the quality of race relations. Broader elements of the exosystem include economic trends and political systems, military and federal policy, social services, education, the mass media and social media (see Box 2-1).

The next ring in the model is the macrosystem, which encompasses cultural systems. This is where military culture meets and intersects with dominant beliefs, assumptions, and worldviews, as well as ideologies in society.

Societal-level influences are the large, macro-level factors that influence well-being, such as gender inequities, income inequality, societal norms, policies, and regulations, which are also at play within the military system.

A significant dynamic in the post-9/11 era is a growing disconnection between the military and the U.S. civilian population it serves. Specifically, Carter and colleagues (2017), as well as others (Fleming, 2010; McFadden, 2017), raise concerns regarding a growing military-civilian divide, including diverging cultures, the separation of communities (e.g., military bases viewed as “gated communities”), the lack of geographic representation, and civilian disconnection from military operations. Importantly, for service members and military families, macrosystem influences extend to U.S. military policy; to DoD assumptions about what constitutes a ready force; to military personnel’s and political leadership’s decision making regarding national security; and to the nature and characteristics of contemporary warfare and missions (Carter et al., 2017).

Finally, in this framework the temporal dimensions—the chronosystem—are critical to understanding the timing of developmental and life-course milestones and events, such as accession or transition to parenthood, as well as socio-historical conditions and their implications for the future force. At the individual level, military events such as deployments may be more or less disruptive for the service member, depending on what life stage that member has reached (Wilmoth and London, 2013). In addition, interventions are often effective at point-of-life transitions, since they can function as opportunities for change from negative to more positive life pathways or the reverse (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2013). The changing nature of warfare and contemporary service in the post-9/11 era is another critical aspect of timing for service members and families.

When the military family is placed at the center, the salient elements and interactions between and among these multilevel layers shift. Both the military and the family, as institutions, have been described as “greedy,” in that each demands commitment, time, and loyalty without regard for work-life-family balance (Segal, 1986). The demands of military life are dictated by military needs, service member readiness, and mission, although they do come with guaranteed employment and wages and with a clear path for advancement (Kleykamp, 2013). By contrast, family members and children are yoked to service member careers and have little control over or decision-making power regarding the timing or location of change of station and deployment.

The concept of tied migration is applicable in the military context and predominately affects women who are partnered with service members and children in military families (Segal et al., 2015). The tied migrant is an individual within a family who moves, as with frequent military “permanent changes of station” (PCSs), but who may not want to move or may

move against her own or her children’s best interests (Cooke, 2013). For military spouses and partners, this pattern of moving interferes with educational attainment, labor participation and earnings, and career development (Hosek et al., 2002; Kleykamp, 2013). For children and adolescents, frequent moving and parental deployment have important and often negative implications for school and peer functioning (Meadows et al., 2016). Burrell and colleagues (2006) also identify work- and duty-related demands as current military-specific stressors, as well as “pressures for military families to conform to accepted standards of behavior, and the masculine nature of the organization” (p. 44).

Relevance of a Multilevel, Ecological Systems Framework for Prevention and Intervention

Ecological or multilevel frameworks are useful in highlighting the differing experiences and accumulation of risk and adversity among service members and families, as well as the social and other environmental influences, including military policies, that can support individual and family readiness and resilience—and they can likewise help in identifying barriers to individual and family well-being (Chmitorz et al., 2018). Moreover, applying a multilevel conceptualization suggests diverse and multiple potential ports of entry for prevention, intervention, and capacity-building in support of service member and family well-being. To be effective, military family support and prevention strategies should consider risk and protective processes across multiple determinants of health and well-being. In this context, the influences at the individual level are processes of personal risk or protection that increase or decrease the likelihood of military children or other family members encountering problematic outcomes.

Ecological and multilevel frameworks are also helpful when considering the diversity of military families and their experiences. While resources have already been allocated to address special needs associated with the families of junior enlisted or Special Operations members as well as families containing members with exceptional needs, additional dimensions of diversity may combine to create other “ecological niches” that also merit consideration. In sum, because multilevel ecological frameworks are useful in highlighting differential accumulation of risk and adversity they are also important in tailoring approaches to distinctive subgroups.

Prevention effects at the individual level, such as student mentoring, aim to change individual-level risk factors. Family stress models (Conger and Conger, 2002; Gewirtz et al., 2018; Simons et al., 2016), which posit that contextual stressors mediate individual, relationship, and family process outcomes, point to family-level intervention efforts. Interpersonal- or relationship-level influences are factors that increase

risk or are protective and that can be attributed to interactions with family, partners, and peers. Prevention strategies that address these influences include the promotion of good communication skills in marital relationships and strengthening parents’ ability to teach children using positive parenting skills.

Community-level influences are factors that increase risk or protection based on formal and informal organizations or social environments, such as schools, recreation, and family support communities. The institutional level for military family well-being includes DoD itself, as well as state and community systems and institutions that issue specific instructions, policies, and regulations (such as the Veterans Health Administration [VHA], veteran serving organizations, and community mental health programs). Community norms concerning where service members and their families live or return to can also shape the risk and protective factors that affect military family well-being.

Overall, multilevel conceptualization indicates that to support the well-being of service members and their families, one needs to recognize diverse and multiple potential ports of entry for prevention, intervention, and capacity-building.

RESILIENCE AND READINESS

Family readiness and resilience are as important for DoD as family well-being, because they are rooted in families’ need to be prepared for and adjust to the inevitable challenges of military life. The concept of resilience has emerged from studies of individuals, families, and communities experiencing stressors like natural disasters, war, isolation, and abuse. Resilience is related to but distinct from well-being, because positive adjustment by itself is not evidence of resilience. In contrast to approaches that prioritize preventing psychopathology, resilience-based approaches emphasize building on a person’s strengths and coping ability (Meadows et al., 2016; Meredith et al., 2011). Resilience is commonly defined as positive adjustment in the aftermath of adversity, and thus cannot be observed in the absence of exposure to adverse experiences (Chmitorz et al., 2018; Meadows et al., 2016). For the purposes of this report and as noted in Chapter 1, we are guided by Masten’s (2015) definition:

the potential or manifested capacity of a dynamic [human] system to adapt successfully to disturbances that threaten the function, survival, or development of the system (p. 187).

This definition is designed to acknowledge that individuals, families, units, and communities are also systems. Like Meadows and colleagues

(2016), we differentiate between potential and manifested resilience. As stated in Chapter 1, we equate potential resilience with readiness, which is similar to the way the DoD Instruction on Family Readiness describes readiness, specifically as “the state of being prepared to effectively navigate the challenges of daily living experienced in the unique context of military service” (DoD, 2012). This latter definition encompasses but is broader than an individual service member’s military operational readiness, stating that it is DoD policy that “the role of personal and family life shall be incorporated into organizational goals related to the recruitment, retention, morale and operational readiness of the military force” (DoD, 2012, p. 2). Thus, for military families, readiness connotes preparation for specific challenges that they may encounter.

The term resilience has been used in many different ways (Bonanno et al., 2015, p. 139), with distinctions sometimes—but not consistently—made between this term and resiliency. For clarity, and similar to Kalisch and colleagues (2015), we use the term resilience to refer to the display of resilient outcomes, resilience processes (or mechanisms) to refer to the dynamics that produce or impede resilience, and resilience factors to refer to the events, characteristics, or circumstances that shape resilience processes or outcomes. Resilience factors may be personal (e.g., hardiness), social (e.g., robust informal support networks), or environmental (e.g., stable community infrastructures) (Chmitorz et al., 2018). Box 2-2 lists seven key principles supported by existing research about resilience among children, youth, adults, and families more generally (not limited to military families).

The committee also examined the key factors in the production of resilience. These are summarized in Table 2-1.

Decades of research have identified common characteristics among children, youth, adults, families, and communities that display resilience, although more is known about resilience in individuals than in families or communities (Bonanno et al., 2015, p. 141). Nevertheless, separating resilience factors and resilience outcomes can be difficult. Positive family functioning, for example, could be construed as either a factor or an outcome—or both. Because family readiness focuses on preparation for adversity with the goal of maximizing resilient outcomes, it may be especially important to focus on the knowledge, skills, and abilities of family members as key resilience factors aimed at improving readiness, and to focus on family well-being when considering resilience outcomes.

Meadows et al. (2016), Walsh (2016) and others (Hawkins et al., 2018; Masten, 2018; Masten and Obradović, 2006) have suggested the following groups of factors as associated with resilience outcomes in families:

- Belief systems—Family members share their confidence that the family can persist and thrive in the face of adversity, feel optimistic

- and able to control their circumstances, and have a sense of meaning about adversity or a worldview that transcends immediate challenges (Henry et al., 2015; Masten and Monn, 2015; Saltzman et al., 2011). Saltzman and colleagues (2011), for example, describe how lack of a shared belief in the service member’s mission can interfere with children’s coping and adaptation. Helping families to build a shared sense of confidence and hope is a strengths-based strategy that supports resilience in this context. Masten and Monn (2015) identify family routines and cultural traditions as important for maintaining a sense of meaning.

- Organizational patterns—Family members spend time together in constructive activities, the family is organized to provide effective support to its members with a good balance of flexibility and connectedness, family members play appropriate roles, and the family has adequate social and economic resources that it

- manages adequately (Masten, 2014; Saltzman et al., 2011). For example, coercive family interactions, inconsistent discipline, and poor coordination between parents can impair functioning in military families. Improving parents’ abilities to teach their children and to co-parent effectively can counteract this threat to resilience (Gewirtz and Zamir, 2014; Saltzman et al., 2011). During times of transition, family organizational patterns often shift, creating both risks and opportunities. For example, they can also increase opportunities for young people to increase their sense of meaning and purpose by helping with family tasks in developmentally appropriate ways (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine 2002; Villarruel et al., 2003).

- Communication/problem solving—Family members communicate openly, clearly, and constructively with each other, respond sensitively to one another’s emotions, show interest in one another’s

TABLE 2-1 Key Factors in the Production of Resilience

| Factor | Description | Variations |

|---|---|---|

| Risk and Vulnerability Factors | Challenges that can threaten or disturb adjustment (Masten and Narayan, 2012) | Exposures are the degree to which individuals or families come into contact with risks (Masten and Narayan, 2012). Exposures vary systematically in relation to factors, including gender, age, race, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. |

| Dosage is the level of exposure to risk, which can be a factor of severity, accumulation, proximity, or breadth of the risk (Masten and Narayan, 2012). | ||

| Risk factors are operational at all times, while vulnerability factors become operational only in high-risk environments. | ||

| Assets | Factors that enhance adaptive capacity | Promotive factors are associated with better outcomes regardless of the presence of risk factors (Masten and Narayan, 2012). |

| Protective factors are associated with better outcomes particularly in the presence of risk factors (Masten and Narayan, 2012). | ||

| Cascades | A reverberation of positive or negative effects across developmental domains within a person, across persons, and across generations and families (Doty et al., 2017; Masten and Cicchetti, 2010; Masten, 2016; Masten and Narayan, 2012; Trail et al., 2017). | Skills or difficulties developed in one domain may generalize to affect others, such as when improvements in parenting lead to improvements in parent and child well-being and in turn reductions in substance use (Patterson et al., 2010). |

| Regardless of levels of support or preparation, some levels of adversity are so high that they exceed the capacity of most systems (individuals, families, or communities) to adapt. |

- problems, and work together to solve problems. Walsh (2003), for example, described how inappropriate withholding of information, suppression of emotions, or ineffective problem solving can heighten anxiety, promote tension, intensify conflict, and impede family members’ ability to provide emotional support to one another. Hawkins and colleagues’ (2018) review of research related to military families indicated that supportiveness among family members was associated with better mental health for all family members (p. 189).

- Physical and psychological health of individual family members—Families members enjoy good emotional, behavioral, and physical health; they possess mastery and hardiness (Meadows et al., 2016). Although physical and psychological health are technically properties of individuals, health problems reverberate beyond individuals and can challenge family resilience (IOM, 2013; Saltzman et al., 2011). Similar to Meadows and colleagues’ (2016) recognition of the importance of hardiness, Masten (2014) identified individual characteristics and skills such as self-efficacy, self-control, emotion regulation, and motivation to succeed as factors associated with resilience. (See Chapter 5 for more detail about individual resilience.)

- Family support system—There is a robust network of informal support from family members and others, such as community members, neighbors, and coworkers. Support systems important to resilience comprise both informal supports that come from social relationships, such as those with family, friends, neighbors, coworkers, and others; and formal supports in the form of resources, programs, and services (Hawkins et al., 2018; Masten, 2014) that provide emotional, instrumental, and other forms of support. Henry and colleagues (2015) refer to the “family maintenance system” as the ability of families to secure sufficient resources to meet their needs, including financial resources, food, shelter, clothing, and education. In their comprehensive review of research related to the resilience of military families, Hawkins and colleagues (2018) observed that the employment challenges and pay gaps experienced by military spouses—especially wives—represent significant challenges to resilience, and also highlight accessibility as an important factor in the adequacy of support systems.

While some might consider it frustrating that no single predictor has emerged as a holy grail for predicting resilience (Bonanno et al., 2015, p. 150), a positive interpretation is that the family systems principle of equifinality means there can be multiple pathways to resilience.

RESILIENCE IN THE MILITARY CONTEXT

DoD has placed considerable emphasis in recent years on the resilience of service members and their families. This includes the Total Force Fitness initiative launched by the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 2013 (Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2013; Jonas et al., 2010), which grew out of the Comprehensive Soldier Fitness effort begun in 2008 by the Army (Cornum et al., 2011). Grounded in principles of positive psychology and resilience, the initiative acknowledges eight domains of fitness—physical, environmental, medical/dental, nutritional, spiritual, psychological, behavioral, and social—and references not only service members but also family members, units, and communities. Its aim is to promote both well-being (primarily subjective well-being, that is feeling good) and resilience (functioning well despite adversity). Linked with this, significant infrastructure has been built in both the Army (Department of the Army, 2014) and the Air Force (Secretary of the Air Force, 2014), particularly regarding physical, medical, and nutritional fitness, to require service members to periodically complete assessments and training to promote fitness across the domains.

Although the Total Force Fitness model incorporates family fitness, and family members are encouraged to participate in resilience assessments, most of the focus has been on service members and units.7 In 2015, at the request of the Defense Center of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury, Meadows and colleagues (2016) conducted a comprehensive review of more than 4,000 documents related to the resilience of military families. They found no standard definitions of family resilience across DoD, although they identified 26 relevant policies, noting that almost all were limited to particular parts of DoD (i.e., branches, components, or program areas) rather than being inclusive.

The Family Readiness Department of Defense Instruction (DoDI) targets three specific areas of readiness for which service members and family members are considered primarily responsible: (i) mobilization and deployment readiness, (ii) mobility and financial readiness, and (iii) personal and family readiness. In the Total Force Fitness8 model, the view of family fitness is more expansive, defining fitness as the ability of a family to use physical, psychological, social, and spiritual resources to prepare for, adapt to, and grow from the demands of military life (Westphal and Woodward, 2010). Bowles at al. (2015) elaborate:

___________________

7 For more information see http://readyandresilient.army.mil/index.html.

8 For more information see https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Library/Instructions/3405_01.pdf?ver=2016-02-05-175032-517.

Fit, or “ready,” families are knowledgeable about potential challenges and equipped with the necessary skills to competently face those challenges. They are aware of and able to use resources available to them. Fit families function successfully in supportive environments that allow for healthy individual development and well-being. Being fit does not make families immune to the daily struggles and hassles of life. This prepares families to respond effectively to difficulties, access support/resources as needed, and develop a better capacity to become resilient when adverse or traumatic situation occur for the family. A key assumption of the MFFM [Military Family Fitness Model]9 is that characteristics of fit families can be learned. Therefore, identifying both adaptive and maladaptive responses to familial stress is important. This concept is analogous to preparing for athletic competition—successful practice improves real-life performance (p. 248).

MEASURING FAMILY READINESS AND RESILIENCE

No gold standard instrument exists inside or outside DoD for assessing resilience in individuals (Windle et al., 2011), and measures of resilience in families lag even further behind (Chmitorz et al., 2018, p. 79). Because definitions of resilience vary widely, measures address a wide variety of constructs, some treating resilience as a stable trait, some ignoring the presence or absence of exposure to adversity (Chmitorz et al., 2018; Wright et al., 2013), some equating resilience with positive adjustment (Wright et al., 2013) and still others conflating resilience factors or mechanisms with outcomes (Windle et al., 2011).

The distinction between readiness and resilience is to some extent arbitrary, because positive adjustment could simultaneously be evidence of resilience following earlier adversity, and evidence of readiness or potential resilience for adversity yet to come. In order to assist military families in being “ready” for adversity, there is a need to focus programs, services, and resources, as well as assessments, on the knowledge, skills, and abilities needed for positive adjustment—or their functional well-being—following adversity. Subjective well-being may be especially important when assessing resilience or positive adjustment in the aftermath of adversity.

Some scholars question whether developing a single instrument to assess a construct as multifaceted and dynamic as family resilience is possible, particularly in the military context. Development of measurement instruments is challenging, because resilience in each family can comprise a different

___________________

9 A comprehensive model aimed at enhancing family fitness and resilience across the life span. This model is intended for use by service members, their families, leaders, and health care providers, but it also has broader applications for all families. The MFFM has three core components: (1) family demands, (2) resources (including individual resources, family resources, and external resources), and (3) family outcomes (including related metrics) (Bowles et al., 2015, p. 246).

mix of characteristics, skills, and resources. Another challenge is measuring constructs at the family level—neither scientific consensus nor statistical tools are yet available to guide appropriate consideration of family dynamics and the vantage points of multiple family members at once (Bonanno et al., 2015; Meadows et al., 2016). Although statistical techniques like multilevel and structural equation modeling make it possible to incorporate the perspectives of multiple family members in statistical analyses, no standard has been established for what the results of such models should show in order to draw conclusions about family readiness or resilience.

Because resilience unfolds in diverse patterns, sometimes over long periods of time, assessments ideally will track change over time. Bonanno and colleagues (2015) suggest that observational measures of family interactions may have the greatest validity (e.g., the Beavers Interactional Competence Scale; Family Interaction Tasks). Such methods are usually too expensive and burdensome for use in widespread screening or monitoring, though less expensive proxies such as “KidVid”—short video vignettes that family members react to (DeGarmo and Forgatch, 2004) or the Five Minute Speech Sample (Narayan et al., 2012)—may be just as reliable and valid in predicting family interactions.

In two recent efforts to build tools for assessing family resilience, Finley and colleagues (2016) and Duncan Lane and colleagues (2017) each developed item pools based on Walsh’s theory of family resilience, which goes beyond seeing individual family members as resources for individual resilience to focus on risk and resilience in the family as a functional unit (Walsh, 2003). In these two studies, the researchers subjected the item pools to pilot testing or expert review, and then administered the trimmed item pools to small convenience samples of individuals in the military (Finley et al., 2016) or general populations (Duncan Lane et al., 2017). The study of military individuals used 40 items administered to 151 individuals, and the general population study used 29 items administered to 113 women with breast cancer. Psychometric properties of both instruments were generally promising. Both efforts were limited, however, by the absence of assessments of adversity, and even more importantly, by the failure to administer the instruments to other family members. Thus, these measures can best be considered preliminary but promising efforts to assess perceptions of the resilience of families.

Measurement of resilience also requires attention to adversity. Family readiness and resilience may be supported by increasing the presence of resilience factors, facilitating the operation of resilience mechanisms, and by reducing exposure to adversity. Separation and relocation are relatively well understood as stressors, but at the present time, DoD does not monitor accumulations of adversity by military families, beyond attempts to track cumulative deployments by service members via the PERSTEMPO

system10 (or Individual Exposure Record). As indicated earlier, accumulations of family transitions can increase the risk of negative outcomes for both children and adults, and robust evidence has emerged that adverse experiences in childhood have far-reaching implications for health during adulthood (Shonkoff et al., 2012).

While there are not yet any comprehensive measures of family resilience that are considered to be “gold standards” by scientists, there are measures with well-established psychometric properties that can be used to assess many of the major components of resilience and readiness. A 2014 National Academy of Sciences report to DoD made specific recommendations regarding strategies and measures that could be fruitfully used to assess prevention efforts; most of these recommendations have yet to be implemented (IOM, 2014, Chapter 5).

Scientific evidence indicates that when adaptive systems in families are functioning well, resilience is the likely result (Masten, 2014). The readiness and resilience of military families are important for service members’ recruitment, retention, performance, satisfaction, well-being, and functioning when they are wounded, ill, or injured. Developing agreed-upon definitions of family readiness and resilience will allow DoD to declare its most relevant indicators, which in turn will make it possible to identify the resilience factors most likely to produce those outcomes, and thus which knowledge, skills, and abilities are most important to promote through military family readiness activities. Some relevant information is undoubtedly already available from the Status of Forces surveys, program record data, and other sources. In the future, monitoring exposures to adversity and tracking levels of preparation and training will be required so that the implications for subsequent resilience can be discerned.

CONCLUSIONS

CONCLUSION 2-1: The Department of Defense lacks an agreed-upon definition of family well-being. Subjective, objective, and functional components of family well-being are all relevant to military recruitment, retention, and performance.

CONCLUSION 2-2: Due to the widespread changes in societal norms and family structures that have occurred in the United States, under

___________________

10 PERSTEMPO is a “congressionally mandated program, directed by the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD). It is the Army’s method to track and manage individual rates of deployment (time away from home), unit training events, special operations/exercises and mission support TDYs.” For more information, see the U.S. Army Human Resources Command Frequently Asked Questions at https://www.hrc.army.mil/content/PERSTEMPO%20FAQs.

standing and addressing military families’ needs today requires greater attention to family diversity and stability.

CONCLUSION 2-3: Service members’ well-being is typically connected to the well-being of their families, and both relate to military recruitment, performance, readiness, and retention. Every service member, including those who are unmarried, is part of some form of family, and all require assistance from informal support systems in order to perform military duties.

CONCLUSION 2-4: The Department of Defense does not have a consistent definition of a family nor does it have a consistent definition and indicators of family readiness and resilience necessary to track relevance, effectiveness, and improvements of programs, services, resources, policies, and practices.

REFERENCES

Adler-Baeder, F., Pittman, J. F., and Taylor, L. (2006). The prevalence of marital transitions in military families. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 44(1–2), 91–106.

Aldwin, C. M. (2014). Rethinking developmental science. Research in Human Development, 11(4), 247–254.

Barlas, F. M., Higgins, W. B., Pflieger, J. C., and Diecker, K. (2013). 2011 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey of Active Duty Military Personnel. Fairfax, VA: ICF International.

Berger, L. M., and Bzostek, S. H. (2014). Young adults’ roles as partners and parents in the context of family complexity. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654(1), 87–109.

Biblarz, T. J., and Stacey, J. (2010). How does the gender of parents matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(1), 3–22.

Bonanno, G. A., and Diminich, E. D. (2013). Annual research review: Positive adjustment to adversity—trajectories of minimal-impact resilience and emergent resilience. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(4), 378–401.

Bonanno, G. A., Romero, S. A., and Klein, S. I. (2015). The temporal elements of psychological resilience: An integrative framework for the study of individuals, families, and communities. Psychological Inquiry, 26(2), 139–169.

Bowles, S. V., Pollock, L. D., Moore, M., Wadsworth, S. M., Cato, C., Dekle, J.W., Meyer, S. W., Shriver, A., Mueller, B., and Stephens, M. (2015). Total Force Fitness: The military family fitness model. Military Medicine, 180(3), 246–258.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Design and Nature. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

_________. (1993). The ecology of cognitive development: Research models and fugitive findings. In R. H. Wozniak and K. Fischer (Eds.), Development in Context: Acting and Thinking in Specific Environments (pp. 3–46). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bronfenbrenner, U., and Morris, P. A. (2007). The bioecological model of human development. In W. Damon and R. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology (6th ed., vol. 1, pp. 793–828). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Burrell, L. M., Adams, G. A., Durand, D. B., and Castro, C. A. (2006). The impact of military lifestyle demands on well-being, Army, and family outcomes. Armed Forces and Society, 33(1), 43–58.

Carter, P., Kidder, K., Schafer, A., and Swick, A. (2017). Working Paper, AVF 4.0: The Future of the All-Volunteer Force. Washington, DC: Center for New American Security.

Carter, S. P., Loew, B., Allen, E. S., Osborne, L., Stanley, S. M., and Markman, H. J. (2015). Distraction during deployment: marital relationship associations with spillover for deployed Army soldiers. Military Psychology, 27(2), 108–114.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018). Well-Being Concepts. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/wellbeing.htm#three.

Cherlin, A. (2010). Demographic trends in the United States: A review of research in the 2000s. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 403–419.

Cherlin, A. J., and Seltzer, J. A. (2014). Family complexity, the family safety net, and public policy. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654(1), 231–239.

Chmitorz, A., Kunzler, A., Helmreich, I., Tüscher, O., Kalisch, R., Kubiak, T., Wessa, M., and Lieb, K. (2018). Intervention studies to foster resilience—A systematic review and proposal for a resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 78–100.

Conger, R. D., and Conger, K. J. (2002). Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(2), 361–373.

Cooke, T. J. (2013). All tied up: Tied staying and tied migration within the United States, 1997 to 2007. Demographic Research, 29(30), 817–836.

Cornum, R., Matthews, M. D., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Comprehensive Soldier Fitness: Building resilience in a challenging institutional context. American Psychologist, 66(1), 4–9.

Cox, A. L. (2018). Invited Comments for the Committee on the Well-Being of Military Families. Presented at a public information-gathering session of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Washington, DC, April 24.