2

Insights from Four Metropolitan Areas

A major thrust of this study involved visiting different metropolitan areas to examine urban flooding in different parts of the United States. The committee selected four places to visit: Baltimore, Maryland, Chicago, Illinois, Houston, Texas, and Phoenix, Arizona. These metropolitan areas vary in rainfall, growth rate, land development patterns, storm water and wastewater infrastructure, and other characteristics that influence flooding.

This chapter addresses Task 1: identify commonalities and differences in the causes, impacts, and recovery and/or mitigation actions across the four case study areas, based on stakeholder workshops, follow-up interviews, site visits, or meetings with subject matter experts. Such approaches emphasize idea generation and information exchange, rather than systematic evaluation. Discussions with stakeholders were structured around the four dimensions of urban flooding: (1) physical (e.g., what causes urban flooding?), (2) social (e.g., who is most affected by urban flooding?), (3) actions and decision making (e.g., what actions could lessen the impacts of urban flooding?), and (4) information (information needs associated with these questions). Key messages heard in these metropolitan areas are presented below.

LOCAL REFLECTIONS FROM BALTIMORE, MARYLAND

Overview

The committee visited its first metropolitan area, Baltimore, on April 24, 2017. The visit began with a full-day workshop that heard from local stakeholders in the morning and federal and state stakeholders in the afternoon (See Appendix B for the Baltimore workshop participants, agenda, and list of site visits). The committee also went on a half-day tour to see firsthand how flooding manifests in Baltimore.

The workshop discussions focused on flooding that occurred in the city of Baltimore and that is managed by the city’s agencies. The participants did not identify with the term urban flooding. Although they noted that flooding occurs along Jones Falls and the low-lying areas near the harbor, the workshop participants seemed more concerned about basement flooding and sinkholes.

Causes of Urban Flooding in Baltimore

The Baltimore metropolitan region is subject to riverine, coastal, and flash flooding. Workshop participants identified several contributors to flooding, including urbanization (particularly development in floodplains), aging and insufficient capacity of storm and sewer infrastructure, subsidence and sea-level rise, and poor building and flood mitigation practices. High concentrations of impervious surfaces and historical flood mitigation actions (e.g., burying streams) have altered natural drainage systems in and around Baltimore. During heavy rainfall or pluvial flood events, storm water can overwhelm the drainage network, causing sewer backups and flooding homes and businesses. Very old storm drains that fail or collapse are the root cause of sinkholes. Sinkholes open up across Baltimore after significant rains, creating road closures and other inconvenient or even dangerous conditions. Sinkhole repair consumes almost all of Baltimore’s dedicated flood management resources.1

People Affected by Urban Flooding in Baltimore

Urban flooding affects a wide array of people in the Baltimore metropolitan area. Comments from workshop and interview participants suggest that the most vulnerable people tend to live in older, flood-prone neighborhoods. Sustained underinvestment in water infrastructure may amplify vulnerability, and in some places, this differential was observed along racial lines. Demographically, the elderly, poor, mentally ill, mobility-constrained, and those with limited experience of flooding were consistently identified as among the most susceptible to flooding effects in the city. Feedback from Baltimore participants also indicated that noncitizens and undocumented immigrants have higher vulnerability due to restricted access to government services, fear of their undocumented status being exposed, and a general lack of trust in officials.

The workshop discussions revealed passions about services available for disenfranchised Baltimoreans. Flooding interrupts service provision at the most basic levels: access to food distribution centers, schools or child care facilities, and regular health services (e.g., dialysis or methadone), especially for low-income residents. Flooded health clinics and mold in schools were named as problems related to flood events, and frustrations ran high about closed or limited access to the facilities that serve Baltimore’s neediest residents. Several respondents commented that 311 calls to report flooding are depressed in socially vulnerable areas due to fear that making calls will result in governmental corrective action unrelated to flooding.

The concerns of the disenfranchised stood in stark contrast to risky development decisions in more affluent neighborhoods. In a new residential complex constructed along the Jones Falls system, for example, floods can reach the second-floor windows (Figure 2.1, left). A bridge from the building’s second level was built to enable egress during severe floods (Figure 2.1, right). In addition, residents of valuable historic properties, which are in the flood channel and flood repeatedly, receive subsidized National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) flood insurance because of the historic status of the buildings.

___________________

1 In-person tour with employees of the City of Baltimore Department of Public Works, April 2017.

SOURCE: Photo courtesy of Lauren Alexander Augustine, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Actions

Flood mitigation, management, and recovery are managed by Baltimore’s Department of Public Works. At the time of the committee’s visit, the department had no dedicated budget for flooding in the city. In contrast, Baltimore works closely on water quality improvements with and through the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and its Chesapeake Bay Program. Resources from EPA and others for water quality improvements are a major driver for capital investments in Baltimore. Workshop participants commented repeatedly about the misalignment of available flood and sinkhole resources and the needs for flood management in Baltimore.

Workshop participants provided numerous suggestions for reducing the adverse impacts of flooding in Baltimore. Many recommended greater participation and influence of local residents on infrastructure investment and disaster recovery decisions. Stakeholders also noted the importance of investing in both the maintenance of and upgrades to the storm water and sanitary sewer systems. Finally, getting ahead of the city’s sinkhole problem would avoid transportation disruptions and resource diversions from proactive mitigation.

LOCAL REFLECTIONS FROM HOUSTON, TEXAS

Overview

The Houston metropolitan area, which includes Harris County, is among the most flood-impacted urban centers in the nation. The catastrophic events of Hurricane Harvey focused national attention on Houston in August 2017 (See Box 2.1). However, area residents have lived with floodwaters for generations.

On July 6, 2017, six weeks before the onset of Hurricane Harvey, the committee met in Houston, Texas, for its second community workshop. Like the Baltimore meeting, the stakeholder workshop was a full-day event, but it focused entirely on urban flooding perspectives from stakeholders at the municipal, county, and state levels (see Appendix C for the Houston meeting participants, agenda, and list of site

visits). In addition, local subject matter experts were invited to give overview presentations about each of the four dimensions of urban flooding. Many of the participants shared personal stories of loss, trauma, or near misses related to a flood event. The Houston and Harris County participants demonstrated a high awareness about urban flooding and its impacts.

Causes of Urban Flooding in Houston

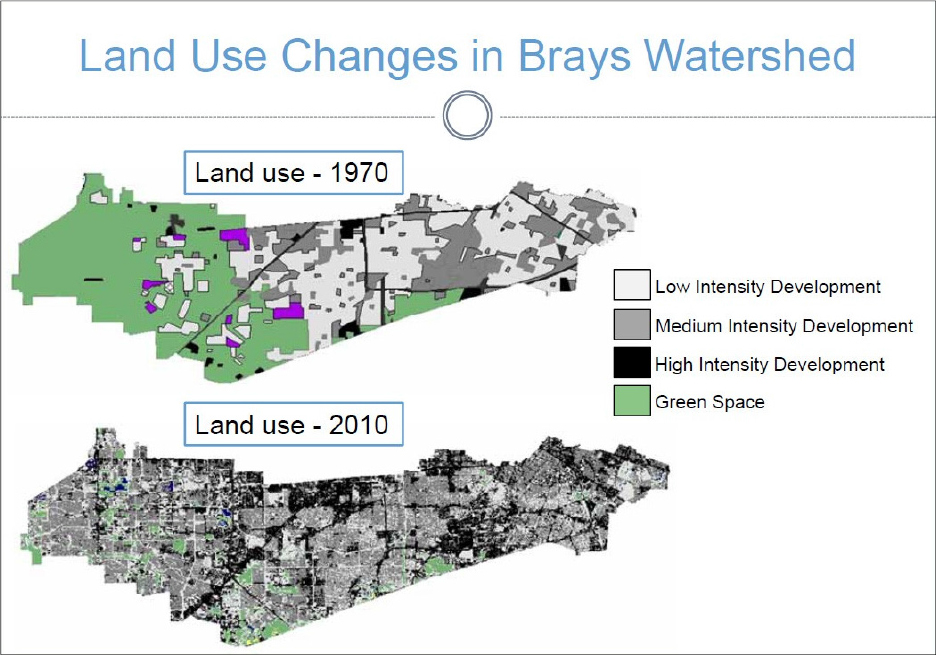

As noted by workshop participants, Houston and Harris County are situated in a flat, low-lying region marked by high rainfall, poorly drained and clay-based soils, and sprawling development. These physical characteristics make the Houston metropolitan area prone to regular and sometimes catastrophic flooding. Furthermore, Houston is one of the fastest growing cities in the nation, due to relatively inexpensive housing, affordable cost of living, proximity to a major commercial port, and a robust economy. The growth of impervious surfaces that accompany development (Figure 2.2) exacerbate the adverse effects of storm water runoff.

SOURCE: Philip Bedient, Rice University.

People Affected by Urban Flooding in Houston

The interviews conducted in Houston indicate that the poorest residents are most likely to live on the lowest-lying land, and so are most subjected to higher flood exposure. The most vulnerable residents were described as poor elderly, renters, minority, disabled, and non-native English speakers. Elderly residents with mobility impairments are more likely to be on a fixed income, to defer maintenance on their homes, and to become targets for post-flood fraud and price gouging by unscrupulous contractors. Renters often suffer when landlords refuse to release them from lease agreements when flood-damaged homes became uninhabitable, or to return lease deposits. Poor families with limited or no savings are more likely to continue living in damaged and moldy homes because they cannot afford repairs or they want to keep their children in their familiar or neighborhood school, often for the benefit of the free meals the schools provide the children. Furthermore, poor homeowners often purchase their properties by means other than conventional mortgages, and so may not have the title documentation required to apply for post-disaster assistance. Undocumented immigrants are particularly vulnerable, often refusing to use shelters due to fears of deportation (Florido, 2017). Recent studies are consistent with these observations, finding heightened flood exposure and vulnerability for Hispanic immigrants, black residents, and those with low socioeconomic status in Houston (Collins et al., 2013; Chakraborty et al., 2019).

Actions

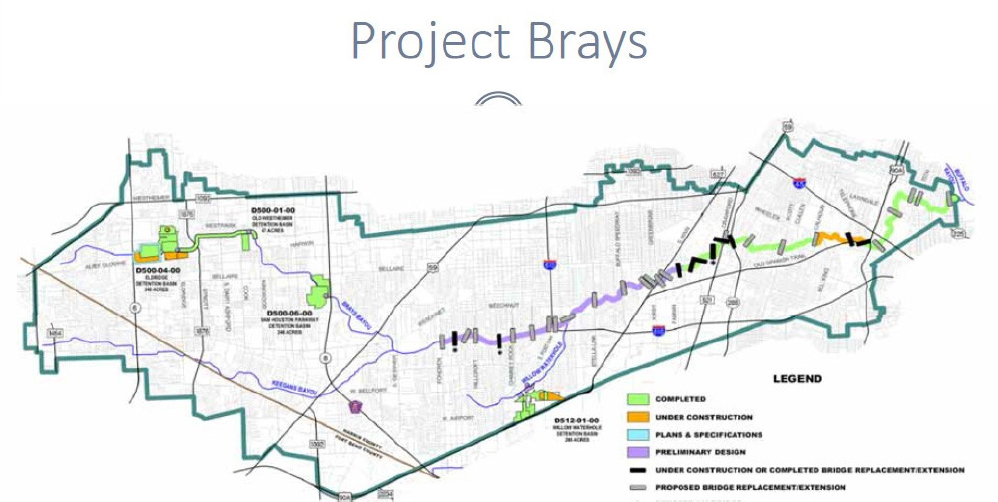

Flooding challenges in the Houston metropolitan area are met with substantial resources. The Harris County Flood Control District has about 380 full-time employees and a total annual budget of $154.6 million,2 of which an estimated $20 million per year is committed to urban flood management. Most of these resources are directed to engineered solutions that gather, redirect, or expedite the flow of water to reduce flooding. Actions taken by the city of Houston focus on small-scale projects, such as widening ditches, building side lot swales, and replacing inlets, sewer lines, and driveway culverts. At the other extreme in terms of scope is Project Brays, which is being carried out by Harris County Flood Control District in collaboration with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) (Figure 2.3). This $550 million engineering project seeks to widen 21 miles of the Brays Bayou, replace or modify 30 bridges, and create 4 new detention basins that collectively will store 3.5 billion gallons of storm water.

___________________

SOURCE: Philip Bedient, Rice University.

One clear message from the workshop was that these engineered solutions to manage storm water infrastructure, drainage, storage, and conveyance functions do not serve all Houstonians equally. Although floods tend to affect the poor and vulnerable first, their voices are the least likely to be heard by government agencies. The workshop participants and interviewees noted that they and their constituents would benefit from coordinated social series with case management intake and follow-up by one point of contact. They also commented on the importance (and often the lack) of an understanding of different cultures and languages when communicating and helping underserved populations find assistance from governmental and nongovernmental sources.

LOCAL REFLECTIONS FROM CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

Overview

On September 19, 2017, the committee visited the Chicago metropolitan area, which includes Cook County, and held its third community workshop. The Chicago visit was similar to Houston’s, and entailed a full-day workshop with local stakeholders and subject matter experts (see Appendix D for the Chicago meeting participants, agenda, and list of site visits). The committee also went on a half-day tour in the Chicago metropolitan area, which included a focus group meeting in the Chatham neighborhood, inspection of an urban garden, and a trip to the quarry storage area of the massive engineering project, the Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP).

Causes of Urban Flooding in Chicago

Urban flooding is a term well understood and embraced by residents in the Chicago metropolitan area. Pluvial, coastal (lake), and riverine flooding are seen in Chicago and Cook County. Aging and undersized storm water infrastructure and a high fraction of impervious surfaces compound the flooding profile of this flat, low-lying, and naturally wet area.

Chicago area homes typically have basements, making them vulnerable to water backing up through floor drains, tubs, toilets, and sinks. Seepage through basement foundation walls is common, as is storm water entering buildings through windows and doors. Overland flow around houses and sewer backups are not always visible outside and are often not reported. A number of workshop participants described their urban flooding experiences of wet basements, soggy carpets, and sewage backups.

People Affected by Urban Flooding in Chicago

A main message from the workshop was the disparity of flood protection in the Chicago metropolitan area, with a strong undertone that voices of people affected by urban flooding go unheard. Specifically, workshop participants described adverse impacts of flooding on low-income elderly residents who have limited economic and physical capacity to repair homes or participate in home mitigation programs that require a cost share. As noted in Baltimore, recent immigrants were identified as particularly vulnerable, stemming from language barriers, lack of trust in authorities, and low familiarity with local hazards. In addition, children were regarded as especially vulnerable to respiratory ailments associated with chronic flooding in homes.

On a site visit to the Chatham neighborhood, a neighborhood of middle-income African American residents and businesses, the committee heard testimony from residents about their problem of repetitive flooding. They also felt that south side neighborhoods such as Chatham receive less flood protection and are given lower priority on major mitigation projects such as TARP than wealthier neighborhoods on the north side of the city.

Actions

In the Chicago region, actions to address urban flooding were evident on several jurisdictional levels. Although people residing outside of Special Flood Hazard Areas commented that government officials are not always attuned to their flooding peril, they saw a high level of political will for better managing urban flooding in the Chicago metropolitan area. Representatives from the offices of U.S. Congressman Quigley and U.S. Senator Durban joined the workshop discussions. In addition, residents in Cook County have established neighborhood flood groups—including RainReady Chatham, Floodlothian Midlothian, Ixchel, and Stop Elmhurst Flooding Now—to share information and updates and to advocate for government assistance. Several have secured investment and solutions to their flooding problems.

At the regional scale, TARP represents major political, financial, and engineering actions to address urban flooding. It encompasses more than 100 miles of tunnels and a reservoir network for managing storm water, including the Thornton Quarry Reservoir, which has the capacity to hold 7.9 billion gallons of storm water (Figure 2.4). At the city scale, Chicago’s Department of Water Management is rebuilding or relining 750 miles of sewer mains and relining 140,000 sewer structures across Chicago over 10 years (Emanuel, 2018). In addition, the Cook County Metropolitan Water Reclamation District is currently funding 85 localized storm water projects across the county, an investment of $403M (MWRD, 2017). At the neighborhood scale, urban gardens watered by storm water effluent are being installed at the Wadsworth Elementary School and elsewhere.

SOURCE: Photo courtesy of Lauren Alexander Augustine, National Academies.

LOCAL REFLECTIONS FROM PHOENIX, ARIZONA

Overview

The committee visited the Phoenix metropolitan area, which includes Maricopa County, on January 24, 2018. Substantial investments in flood mitigation have been made in this arid region. The committee engaged a few subject matter experts, in lieu of a workshop with a variety of local stakeholders, to discuss city, county, and state actions and decision-making processes that may hold lessons for other metropolitan areas in the United States. The committee also toured areas in the city of Phoenix and Maricopa County during the field trip (see Appendix E for the Phoenix meeting agenda and list of site visits).

Causes of Urban Flooding in Phoenix

Phoenix is the second fastest growing city in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). The experts at the meeting attributed urban flooding in the Phoenix area to rapid population growth, the area’s flat topography with surrounding mountains, intense rainfall, sandy soil and hardpan, extensive impervious surfaces (Figure 2.5), and land use changes associated with urbanization. Together, these characteristics lead to flash floods during high-intensity rainstorms. In a flash flood, the peak flow occurs in just minutes and may overwhelm drainage systems.

SOURCE: Photo courtesy of Lauren Alexander Augustine, the National Academies.

Actions

Phoenix and Maricopa County are addressing flooding with substantial infrastructure investments, community engagement, and innovative approaches to flood control. An example includes the Indian Bend Wash, which the committee visited in its field trip. The Indian Bend Wash project runs through Scottsdale, Arizona, in Maricopa County. In the 1960s, USACE recommended a huge concrete channel similar to that shown in Figure 2.6, left. After citizen opposition, however, the City Council negotiated the creation of Eldorado Park, a federally funded open space by the wash.

In the early 1970s, the worst flood in city history prompted development of an 11-mile flood-control project, doubling as a greenbelt, along the wash. The cooperation of local landowners was essential. Engineers laid out the perimeter of the wash, and the city passed land use ordinances that prevented development in the wash and decreased development density immediately outside it. The project was completed in 1984. In addition to providing a conduit for up to 30,000 cubic feet per second of flows and excess floodwater, the Indian Bend Wash also provides residents with an open-space area for hiking, biking, and fishing (Figure 2.6, right).

Experts at the meeting described several other examples of successful interagency coordination. For example, the Flood Control District of Maricopa County manages a flood warning system to facilitate communication among multiple government jurisdictions. Federal agencies (U.S. Geological Survey [USGS], National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, USACE, and FEMA) provide information to the Maricopa County Flood Control District, and the Flood Control District provides information to other county departments, cities, and the Arizona Department of Transportation. An example at the state level is the Arizona Department of Transportation Resiliency Program, in which participating agencies share information, identify common problems and shared solutions, and develop policies and regulations to mitigate urban flooding. One such project is a 5-year, $1 million partnership with the USGS. The USGS is monitoring storms, collecting data, and providing hardware, software, and capabilities to measure surface water flow, and the Arizona Department of Transportation is using these assets to plan for and respond to floods.

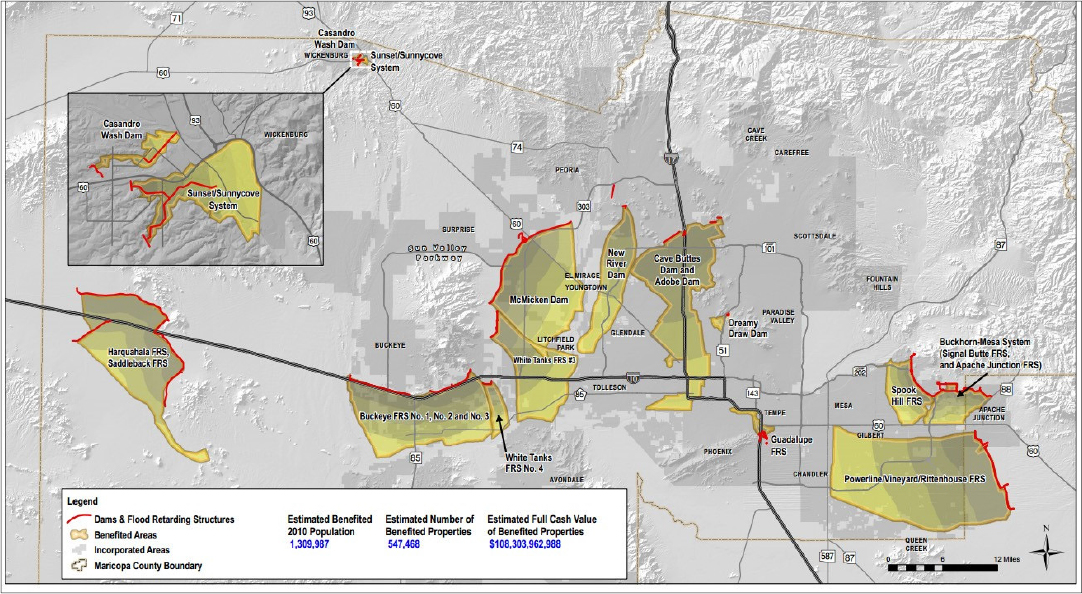

The City of Phoenix and Maricopa County have substantial resources dedicated to mitigate the impacts of urban flooding. Coordination among and across the various jurisdictions involved in urban flooding is central to mitigation efforts. For example, the Maricopa County Flood Control District manages a range of capital projects in partnership with other agencies, including dams built by USACE and flood retardation structures built by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (Figure 2.7).

SOURCE: Steve Waters, Maricopa County.

COMMONALITIES AND DIFFERENCES AMONG THE FOUR METROPOLITAN AREAS

The four case study workshops, site visits, and interviews showed that each metropolitan area has its own flavor of urban flooding. In addition, the local conversations that revealed that people in the same place can have very different understandings and experiences of floods, but they all share a desire for better understanding and for better management of urban flooding. Below is a summary of key similarities and differences among the case study areas (Task 2), as identified by the case study participants. The key messages are organized by the physical, social, information, and actions and decision-making dimensions of urban flooding.

Physical Dimensions: In all of the four metropolitan areas visited, the intensity, location, and duration of urban flooding was influenced by land use, land cover, development patterns, and the age, condition, and design capacity of storm water infrastructure. A key difference among the case study areas was the sources of flooding: riverine (Baltimore), coastal (Baltimore, Houston, and Chicago [Great Lakes]), flash (Phoenix), and pluvial flooding (all four areas), as well as sewer backups (Chicago and Baltimore). Common drivers related to decision making—land development and design or maintenance of infrastructure—were seen to amplify the intensity and influence the location of flood impacts in each of these metropolitan areas.

Social Dimensions: Across the metropolitan areas, people expressed that the effects of urban flooding are felt differently across different urban populations. Flooding stories in Houston, Chicago, and Baltimore described flood impacts across the economic spectrum of residents. However, the workshop sessions and interviews painted a clear picture that the poor, racial and ethnic minorities, the elderly, renters, non-native English speakers and those with mobility challenges were disproportionately affected by floods. A big difference across the metropolitan areas was the varying level of citizen empowerment. The committee heard about places with highly organized neighborhood and citizen groups (Chicago); with

low levels of citizen engagement (Baltimore); and with a mix of those feeling empowered and disempowered (Houston).

Information Dimensions: FEMA Flood Insurance Rate Maps were used widely in all four metropolitan areas, but workshop participants in each area lamented their limitations for understanding urban flooding. Some counties are working to fill the information gap. For example, Harris County has developed local flood models, and Maricopa County and its partners are producing flood maps for transportation purposes as well as flood warnings. Another similarity among the four metropolitan areas was a poor understanding or lack of reliable information on the social impacts and economic costs of urban floods.

Actions and Decision-Making Dimensions: People in each metropolitan area wanted ongoing urban flood management efforts, and they noted the importance and the challenges of working toward solutions to urban flooding across jurisdictional divides. The range of collaborative projects across and among jurisdictions resulted in substantial engineering projects (TARP in Chicago or Brays Bayou in Houston), large-scale blue-green solutions for flood (Indian Bend Wash in Maricopa County), and information-sharing efforts for flash flood warning systems (Arizona Department of Transportation Resilience Program). The challenges and successes of collaboration illustrated in these stories underscore the need for coordination among entities that manage urban flooding.

Finding: Each of the study areas (Baltimore, Houston, Chicago, and Phoenix) has a unique flood hazard and manages urban flooding in its own way, using a tailored mix of federal, state, local, and nongovernmental financial and information resources. In each metropolitan area visited, the impacts of flooding are particularly felt by disenfranchised populations. All four dimensions (physical, social, information, and actions and decision making) are needed to understand and manage urban flooding.

This page intentionally left blank.